Intranasal Dental Repulsion of a Displaced Cheek Tooth in an Arabian Filly

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Case Description

2.1. Clinical Presentation

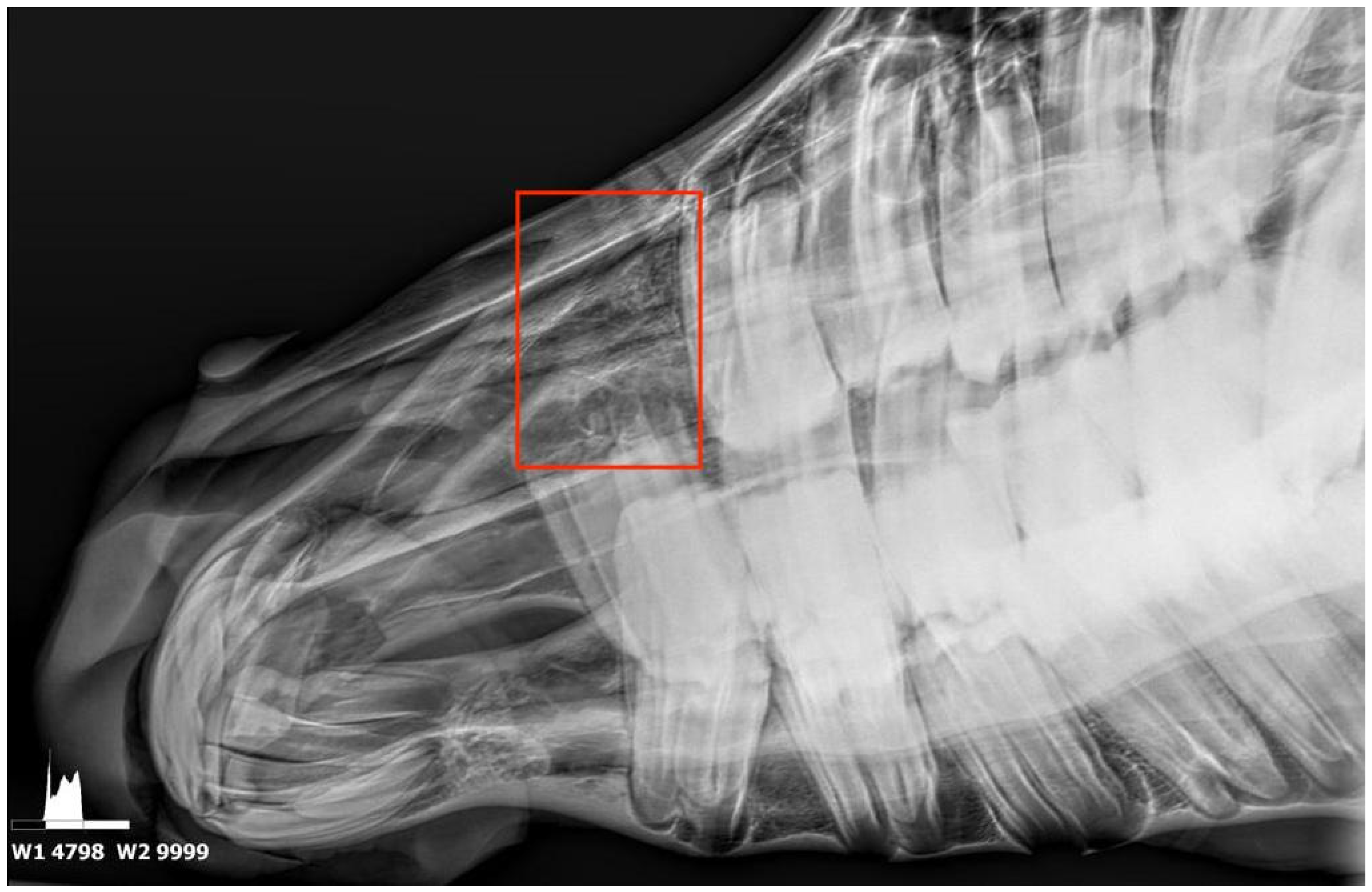

2.2. Diagnostic Imaging

2.3. Surgery

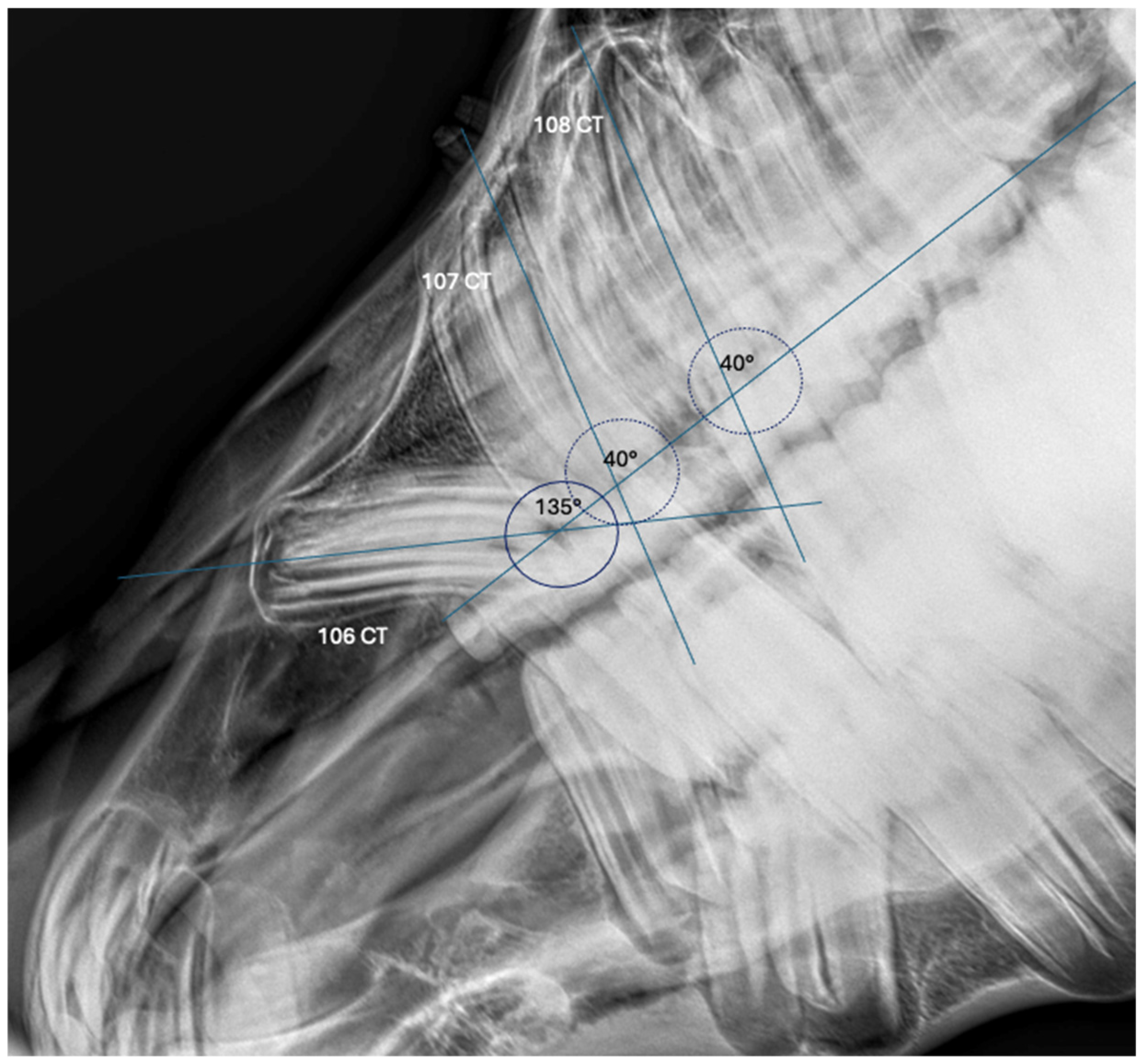

2.3.1. Surgical Planning

2.3.2. Preparation of the Patient and Surgical Procedure

2.4. Post-Operative Management

2.5. Long-Term Follow-Up

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dixon, P.M.; Dacre, I. A Review of Equine Dental Disorders. Vet. J. 2005, 169, 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, C.J. Recent Developments in Equine Dentistry. N. Z. Vet. J. 2020, 68, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peffers, A. Clinical Insights: Equine Dentistry in 2022. Equine Vet. J. 2022, 54, 841–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, F.J. Equine Cheek Tooth Extraction: A Surgical Challenge; Auburn University: Auburn, AL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Witte, T. Developments and Options Un Equine Cheek Teeth Extraction. Vet. Times 2013, 43, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, C. Equine Dental Anatomy and Oral Examination; Texas A&M University: College Station, TX, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, C.; Henry, T. Dental Anatomy and Nomenclature; Texas A&M University: College Station, TX, USA; UC Davis Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital: Davis, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stauffer, S.; Cordner, B.; Dixon, J.; Witte, T. Maxillary Nerve Blocks in Horses: An Experimental Comparison of Surface Landmark and Ultrasound-Guided Techniques. Vet. Anaesth. Analg. 2017, 44, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Dixon, P.M.; Du Toit, N.; Staszyk, C. Equine Dental Anatomy. In Equine Dentistry and Maxillofacial Surgery; Easley, J., Dixon, P.M., Du Toit, N., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle, UK, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 58–98. [Google Scholar]

- Loch, W.; Melvin, B. Determining Age of Horses by Their Teeth. Univ. Mo. Ext. 1998. Available online: https://extension.missouri.edu/publications/g2842 (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Dixon, P.M.; Du Toit, N. Dental Anatomy. In Equine Dentistry, 3rd ed.; Easley, J., Dixon, P.M., Schumacher, J.S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 1, pp. 51–76. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, P.M.; Tremaine, W.H.; Pickles, K.; Kuhns, L.; Hawe, C.; Mccann, J.; Mcgorum, B.C.; Railton, D.I.; Brammer, S. Equine Dental Disease Part 3: A Long-Term Study of 400 Cases: Disorders of Wear, Traumatic Damage and Idiopathic Fractures, Tumours and Miscellaneous Disorders of the Cheek Teeth. Equine Vet. J. 2000, 32, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caramello, V.; Zarucco, L.; Foster, D.; Boston, R.; Stefanovski, D.; Orsini, J.A. Equine Cheek Tooth Extraction: Comparison of Outcomes for Five Extraction Methods. Equine Vet. J. 2020, 52, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, P.M.; Tremaine, W.H.; Pickles, K.; Kuhns, L.; Hawe, C.; Mccann, J.; Mcgorum, B.C.; Railton, D.I.; Brammer, S. Equine Dental Disease Part 2: A Long-Term Study of 400 Cases: Disorders of Development and Eruption and Variations in Position of the Cheek Teeth. Equine Vet. J. 1999, 31, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, P.M.; Vlaminck, L. Abnormalities of Craniofacial Development and of Dental Development and Eruption. In Equine Dentistry and Maxillofacial Surgery; Easley, J., Dixon, P., Du Toit, N., Eds.; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle, UK, 2022; pp. 141–160. [Google Scholar]

- Colyer, F. Variations and Diseases of the Teeth of Horses. Trans. Odontol. Soc. Great Br. 1906, 39, 154–163. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, W.R. Dental Surgery in Horses. In Proceedings of the 14th Annual Congress of the British Equine Veterinary Association, Birmingham, UK, 13 September 2014; BEVA: Harrogate, UK, 1965; pp. 34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, G.J. A Study of Dental Disease in the Horse. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, G.B. Retention of Permanent Cheek Teeth in Three Horses. Equine Vet. Educ. 1993, 5, 299–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, E. Zahne. In Handbuch Der Speziellen Pathologischen Anatomie der Haustiere, 3rd ed.; Pallaske, G., Stunzi, H., Band, V., Eds.; Verlag Paul Parey: Berlin, Germany, 1962; pp. 121–265. [Google Scholar]

- Robert, M.; Gangl, M.C.; Lepage, O. A Case of Facial Deformity Due to Bilateral Developmental Maxillary Cheek Teeth Displacement in an Adult Horse. Can. Vet. J. 2010, 51, 1152. [Google Scholar]

- Earley, E.T.; Rawlinson, J.E.; Baratt, R.M. Complications Associated with Cheek Tooth Extraction in the Horse. J. Vet. Dent. 2013, 30, 220–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, M.K.; Henry, T.J. Standing Intraoral Extractions of Cheek Teeth Aided by Partial Crown Removal in 165 Horses (2010–2016). Equine Vet. J. 2018, 50, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramzan, P.H.L.; Dallas, R.S.; Palmer, L. Extraction of Fractured Cheek Teeth under Oral Endoscopic Guidance in Standing Horses. Vet. Surg. 2011, 40, 586–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langeneckert, F.; Witte, T.; Schellenberger, F.; Czech, C.; Aebischer, D.; Vidondo, B.; Koch, C. Cheek Tooth Extraction Via a Minimally Invasive Transbuccal Approach and Intradental Screw Placement in 54 Equids. Vet. Surg. 2015, 44, 1012–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horbal, A.; Reardon, R.J.M.; Liuti, T.; Dixon, P.M. Evaluation of Ex Vivo Restoration of Carious Equine Maxillary Cheek Teeth Infundibulae Following Debridement with Dental Drills and Hedstrom Files. Vet. J. 2017, 230, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earley, E.; Rawlinson, J.T. A New Understanding of Oral and Dental Disorders of the Equine Incisor and Canine Teeth. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Equine Pract. 2013, 29, 273–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, P.M.; Dacre, I.; Dacre, K.; Tremaine, W.H.; McCann, J.; Barakzai, S. Standing Oral Extraction of Cheek Teeth in 100 Horses (1998–2003). Equine Vet. J. 2005, 37, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremaine, W.H.; Dixon, P.M. A Long-Term Study of 277 Cases of Equine Sinonasal Disease. Part 2: Treatments and Results of Treatments. Equine Vet. J. 2001, 33, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R.; Reardon, R.J.M.; James, O.; Wilson, C.; Dixon, P.M. A Long-Term Study of Equine Cheek Teeth Post-Extraction Complications: 428 Cheek Teeth (2004–2018). Equine Vet. J. 2020, 52, 811–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coomer, R.P.C.; Fowke, G.S.; Mckane, S. Repulsion of Maxillary and Mandibular Cheek Teeth in Standing Horses. Vet. Surg. 2011, 40, 590–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Spadari, A.; Saragoni, G.; Meistro, F.; Ralletti, M.V.; Marzari, F.; Rinnovati, R. Intranasal Dental Repulsion of a Displaced Cheek Tooth in an Arabian Filly. Animals 2025, 15, 772. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15060772

Spadari A, Saragoni G, Meistro F, Ralletti MV, Marzari F, Rinnovati R. Intranasal Dental Repulsion of a Displaced Cheek Tooth in an Arabian Filly. Animals. 2025; 15(6):772. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15060772

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpadari, Alessandro, Giuditta Saragoni, Federica Meistro, Maria Virginia Ralletti, Francesca Marzari, and Riccardo Rinnovati. 2025. "Intranasal Dental Repulsion of a Displaced Cheek Tooth in an Arabian Filly" Animals 15, no. 6: 772. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15060772

APA StyleSpadari, A., Saragoni, G., Meistro, F., Ralletti, M. V., Marzari, F., & Rinnovati, R. (2025). Intranasal Dental Repulsion of a Displaced Cheek Tooth in an Arabian Filly. Animals, 15(6), 772. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15060772