Comparative Evaluation of a Domestic Automatic Milking System and a Commercial System: Effects of Parity on Milk Performance and System Capacity

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval and Feeding Management

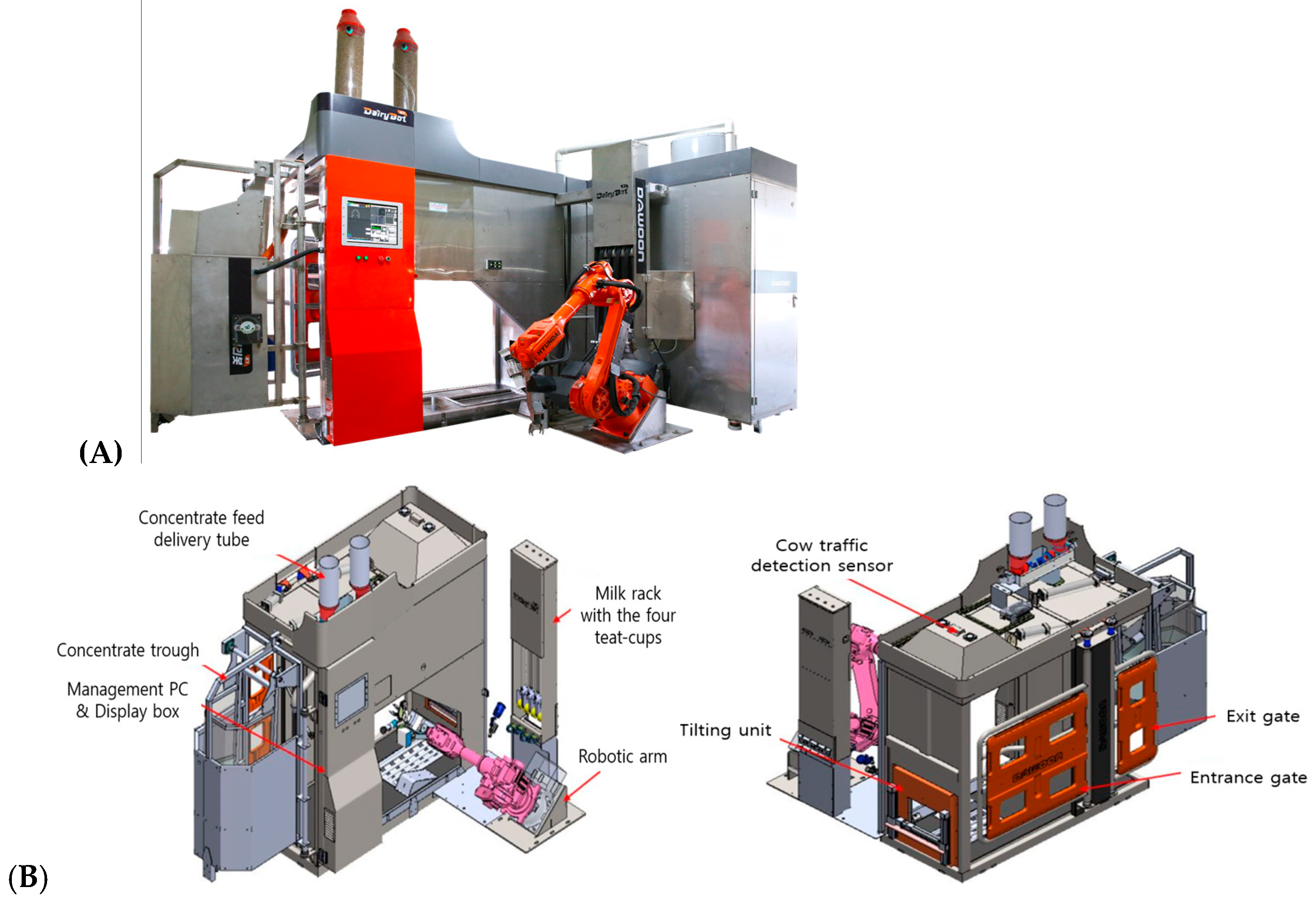

2.2. Structure and Operation of Domestic Automatic Milking System (AMS-K)

2.3. Operation of Domestic and Imported AMS According to Parity

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Milking Performance of AMS-K

3.2. Comparison of Milking Characteristics of AMS-K and AMS-C by the Parity of Dairy Cows

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wildridge, A.M.; Thomson, P.C.; Garcia, S.C.; Jongman, E.C.; Kerrisk, K.L. Transitioning from conventional to automatic milking: Effects on the human-animal relationship. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 1608–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões Filho, L.M.; Lopes, M.A.; Brito, S.C.; Rossi, G.; Conti, L.; Barbari, M. Robotic milking of dairy cows: A review. Semin. Ciênc. Agrár. 2020, 41, 2833–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dairy Policy Institute. 2024 Dairy Farm Management Survey; Dairy Policy Institute of Korea Dairy Beef Association: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2024; pp. 30–31. [Google Scholar]

- de Koning, K.; Rodenburg, J. Automatic milking: State of the art in Europe and North America. Int. Dairy Top. 2004, 3, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J.A.; Siegford, J.M. Invited review: The impact of automatic milking systems on dairy cow management, behavior, health, and welfare. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 2227–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, C.; Barkema, H.W.; DeVries, T.J.; Rushen, J.; Pajor, E.A. Effect of transitioning to automatic milking systems on producers’ perceptions of farm management and cow health in the Canadian dairy industry. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 2404–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ki, K.S. The success of localization of robotic milking mahines will accelerate the domestic digital precision dairy industry. Green Mag. 2022, 201, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Gargiulo, J.I.; Lyons, N.A.; Kempton, K.; Armstrong, D.A.; Garcia, S.C. Physical and economic comparison of pasture-based automatic and conventional milking systems. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 8231–8240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gygax, L.; Neuffer, I.; Kaufmann, C.; Hauser, R.; Wechsler, B. Comparison of functional aspects in two automatic milking systems and auto-tandem milking parlors. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 4265–4274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persson Waller, K.; Westermark, T.; Ekman, T.; Svennersten-Sjaunja, K. Milk leakage—An increased risk in automatic milking systems. J. Dairy Sci. 2003, 86, 3488–3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, A.; Pereira, J.M.; Amiama, C.; Bueno, J. Estimating efficiency in automatic milking systems. J. Dairy Sci. 2012, 95, 929–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, M.A.; Pearson, R.E.; Lukes-Wilson, A.J. Effects of milking frequency and selection for milk yield on productive efficiency of Holstein cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1990, 73, 1603–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, M.; Svennersten-Sjaunja, K.; Wiktorsson, H. Feeding patterns and performance of cows in controlled cow traffic in automatic milking systems. J. Dairy Sci. 2005, 88, 3913–3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorati, L.; Speroni, M.; Lolli, S.; Calza, F. Effect of concentrate feeding on milking frequency and milk yield in an automatic milking system. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 4, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollenhorst, H.; Hidayat, M.M.; van den Broek, J.; Neijenhuis, F.; Hogeveen, H. The relationship between milking interval and somatic cell count in automatic milking systems. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 4531–4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mac-Lean, P.A.B.; de Oliveira Campos, L.A.; Cremasco, C.P.; Satolo, E.G.; Rotoli, L.U.M.; Escobar, O.; Feitosa, S.V.B. Impact of different stall layouts with robotic milking systems on the behavioral pattern of multiparous cows. JDS Commun. 2024, 5, 500–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Soest, B.J.; Matson, R.D.; Santschi, D.E.; Duffield, T.F.; Steele, M.A.; Orsel, K.; Pajor, E.A.; Penner, G.B.; Mutsvangwa, T.; DeVries, T.J. Farm-level nutritional factors associated with milk production and milking behavior on Canadian farms with automated milking systems. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 4409–4425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlström, C.; Pettersson, G.; Johansson, K.; Strandberg, E.; Stålhammar, H.; Philipsson, J. Feasibility of using automatic milking system data from commercial herds for genetic analysis of milkability. J. Dairy Sci. 2013, 96, 5324–5332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, M.T.M.; LeBlanc, S.J.; Pajor, E.A.; Wright, T.C.; DeVries, T.J. Behavior and productivity of cows milked in automated systems before diagnosis of health disorders in early lactation. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 4343–4356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Borne, B.H.P.; van Grinsven, N.J.M.; Hogeveen, H. Trends in somatic cell count deteriorations in Dutch dairy herds transitioning to an automatic milking system. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 6039–6050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aerts, J.; Sitkowska, B.; Piwczyński, D.; Kolenda, M.; Önder, H. The optimal level of factors for high daily milk yield in automatic milking system. Livest. Sci. 2022, 264, 105035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, F.A.N.; Lopes, M.A.; Lima, A.L.R.; De Almeida Junior, G.A.; Novo, A.L.M.; de Camargo, A.C.; Barbari, M.; Brito, S.C.; Reis, E.M.B.; Damasceno, F.A.; et al. Comparative analysis of milking and behavior characteristics of multiparous and primiparous cows in robotic systems. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc 2024, 96, e20221078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanowska, J.; Plavsic, M.; Ipema, A.H.; Hendriks, M.M.W.B. The effect of omitted milking on the behaviour of cows in the context of cluster attachment failure during automatic milking. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2000, 67, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spolders, M.; Meyer, U.; Flachowsky, G.; Coenen, M. Differences between primiparous and multiparous cows in voluntary milking frequency in an automatic milking system. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2004, 3, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y. 2025 Dairy Statistics Yearbook; Korea Dairy Committee: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2025; pp. 59–126. [Google Scholar]

- Crocco, L.; Magro, S.; Costa, A.; Penasa, M.; Marchi, M.D. Milk yield and quality of dairy cows transitioning from milking parlour to automatic milking system. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2025, 24, 1167–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, T.C.; Lage, C.F.A.; Bruno, D.R.; Fausak, E.D.; Endres, M.I.; Ferreira, F.C.; Lima, F.S. Geographical trends for automatic milking systems research in non-pasture-based dairy farms: A scoping review. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 7725–7736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Item | TMR (% of DM) | Concentrations (% of DM) |

|---|---|---|

| Ingredient composition | ||

| Corn silage | 18.01 | - |

| Pasture hay | 26.34 | - |

| Alfalfa | 8.08 | - |

| Timothy | 8.27 | - |

| Soybean meal | 2.01 | - |

| Beet pulp | 6.02 | - |

| Cottonseed | 8.06 | - |

| Commercial concentrate | 21.86 | - |

| Calcium carbonate | 0.07 | - |

| Vitamin-mineral mix | 0.07 | - |

| Chemical analysis | ||

| Moisture (% of as fed) | 31.66 | 12.27 |

| Crude protein | 14.97 | 22.49 |

| Ether extract | 3.83 | 4.33 |

| Crude fiber | 25.81 | 9.18 |

| Crude ash | 8.52 | 7.06 |

| Neutral detergent fiber | 54.24 | 32.44 |

| Acid detergent fiber | 32.24 | 15.96 |

| TDN 1 | 65.70 | 83.97 |

| DE 2, Mcal/kg | 2.89 | 3.70 |

| NEL 3, Mcal/kg | 1.56 | 1.93 |

| Specifications | AMS-K 1 | AMS-C 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Milking facility design | Single stall | Single stall |

| Robot arm | 6-axis industrial manipulator | Special manipulator |

| Udder cleaning | Washing within teat-cup | Cleaning brush |

| Time limit for milking, h | 6 h after a previous milking | 6 h after a previous milking |

| Milking delay alert, h | 12 h after a previous milking | 12 h after a previous milking |

| Item | Operation Period (Month) | SEM | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Milk yield (kg/milking) | 13.81 b | 13.95 b | 15.99 a | 0.08 | <0.001 |

| Daily milk yield (kg) | 34.90 b | 33.76 c | 36.30 a | 0.24 | <0.001 |

| Milking frequency (no.) | 2.53 a | 2.42 b | 2.27 c | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Milking intervals (hr) | 9.37 c | 9.68 b | 10.34 a | 0.04 | <0.001 |

| Milking-stall occupation (min) | 10.35 c | 10.82 b | 11.39 a | 0.07 | <0.001 |

| Teat-cup attachment (min) | 1.80 c | 2.13 b | 2.82 a | 0.03 | <0.001 |

| Milking time (min) | 8.55 | 8.56 | 8.69 | 0.07 | 0.724 |

| Item | Operation Period (Month) | SEM | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Milk fat (%) | 3.47 | 3.53 | 3.52 | 0.02 | 0.083 |

| Milk protein (%) | 3.38 b | 3.41 a | 3.31 c | 0.01 | 0.003 |

| Lactose (%) | 4.74 a | 4.73 a | 4.69 b | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Somatic cell score 1 (units) | 5.31 b | 5.45 a | 5.30 c | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Mastitis detection index | 6.59 b | 6.45 b | 7.04 a | 0.04 | <0.001 |

| Milk electrical conductivity (mS/cm) | 5.37 a | 5.35 a | 5.26 b | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Maximum milk conductivity (mS/cm) | 5.88 a | 5.92 a | 5.75 b | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Blood in milk (mg/L) | 0.43 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.365 |

| Milk flow (kg/min) | 0.60 c | 0.62 b | 0.69 a | 0.00 | <0.001 |

| Maximum milk flow (kg/min) | 4.77 b | 4.80 b | 5.12 a | 0.02 | <0.001 |

| Milking efficiency (kg/min) | 2.45 b | 2.44 b | 2.56 a | 0.01 | <0.001 |

| Item | AMS-K 1 | AMS-C 2 | SEM | p-Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primiparous | Multiparous | Primiparous | Multiparous | Parity 3 (P) | AMS (A) | P × A | ||

| Cows per AMS (no.) | 15 | 10 | 12 | 13 | - | - | - | - |

| Days in milking (day) | 186.72 | 185.88 | 182.75 | 190.95 | 4.13 | 0.658 | 0.948 | 0.586 |

| Milking success (%) | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | - | - | - | - |

| Teat-cup attachment frequency (times/milking) | 4.72 | 5.01 | 5.09 | 5.04 | 0.79 | 0.411 | 0.177 | 0.249 |

| Milking-stall occupation (min) | 9.38 | 12.81 | 6.88 | 6.38 | 0.56 | 0.248 | <0.001 | 0.036 |

| Teat-cup attachment (min) | 2.26 | 2.42 | 0.94 | 0.90 | 0.07 | 0.411 | 0.177 | 0.249 |

| Milking time (min) | 7.21 | 9.22 | 5.22 | 5.08 | 0.17 | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Milking frequency (times/day) | 2.35 | 2.48 | 2.74 | 2.83 | 0.03 | 0.321 | <0.001 | 0.107 |

| Milking interval (hr) | 10.04 | 10.46 | 8.01 | 8.68 | 0.13 | 0.028 | <0.001 | 0.617 |

| Milk yield per milking (kg) | 13.61 | 17.86 | 11.58 | 13.37 | 0.25 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.006 |

| Milk yield per day (kg) | 32.33 | 40.16 | 32.93 | 39.25 | 0.54 | <0.001 | 0.870 | 0.426 |

| Milking efficiency (kg/min) | 2.20 | 2.28 | 2.73 | 2.87 | 0.06 | 0.325 | <0.001 | 0.764 |

| Milk flow rate (kg/min) | 0.56 | 0.89 | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Milk fat (%) | 3.31 | 3.46 | 3.95 | 4.05 | 0.05 | 0.141 | <0.001 | 0.764 |

| Milk protein (%) | 3.42 | 3.22 | 3.20 | 3.19 | 0.02 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.007 |

| Lactose (%) | 4.89 | 4.57 | 4.72 | 4.63 | 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.088 | <0.001 |

| Somatic cell score 4 (units) | 5.37 | 5.32 | 4.98 | 5.21 | 0.01 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Milking capacity 5 (cows/unit) | 54.45 | 37.77 | 63.66 | 66.45 | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lim, D.-H.; Eom, J.S.; Park, S.M.; Park, J.; Kim, D.H.; Choi, T.; Choi, Y.K.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y. Comparative Evaluation of a Domestic Automatic Milking System and a Commercial System: Effects of Parity on Milk Performance and System Capacity. Animals 2025, 15, 3649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243649

Lim D-H, Eom JS, Park SM, Park J, Kim DH, Choi T, Choi YK, Kim J, Kim Y. Comparative Evaluation of a Domestic Automatic Milking System and a Commercial System: Effects of Parity on Milk Performance and System Capacity. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243649

Chicago/Turabian StyleLim, Dong-Hyun, Jun Sik Eom, Seong Min Park, Jihoo Park, Dong Hyeon Kim, Taejeong Choi, Young Kyung Choi, Jongseon Kim, and Younghoon Kim. 2025. "Comparative Evaluation of a Domestic Automatic Milking System and a Commercial System: Effects of Parity on Milk Performance and System Capacity" Animals 15, no. 24: 3649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243649

APA StyleLim, D.-H., Eom, J. S., Park, S. M., Park, J., Kim, D. H., Choi, T., Choi, Y. K., Kim, J., & Kim, Y. (2025). Comparative Evaluation of a Domestic Automatic Milking System and a Commercial System: Effects of Parity on Milk Performance and System Capacity. Animals, 15(24), 3649. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243649