Preliminary Investigation of Cecal Microbiota in Experimental Broilers Reared Under the Aerosol Transmission Lameness Induction Model

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Use Statement

2.2. Experimental Design

2.2.1. Pen Design and Allocation

2.2.2. Treatment Design

2.3. Lameness Incidence

2.4. Cecal Content Collection

2.5. 16S V3–V4 Sequencing of Cecal Content Samples

2.6. Data Analysis

2.6.1. Cumulative Lameness Incidence Analysis

2.6.2. Cecal Community

2.6.3. Statistical Measures of Diversity

3. Results

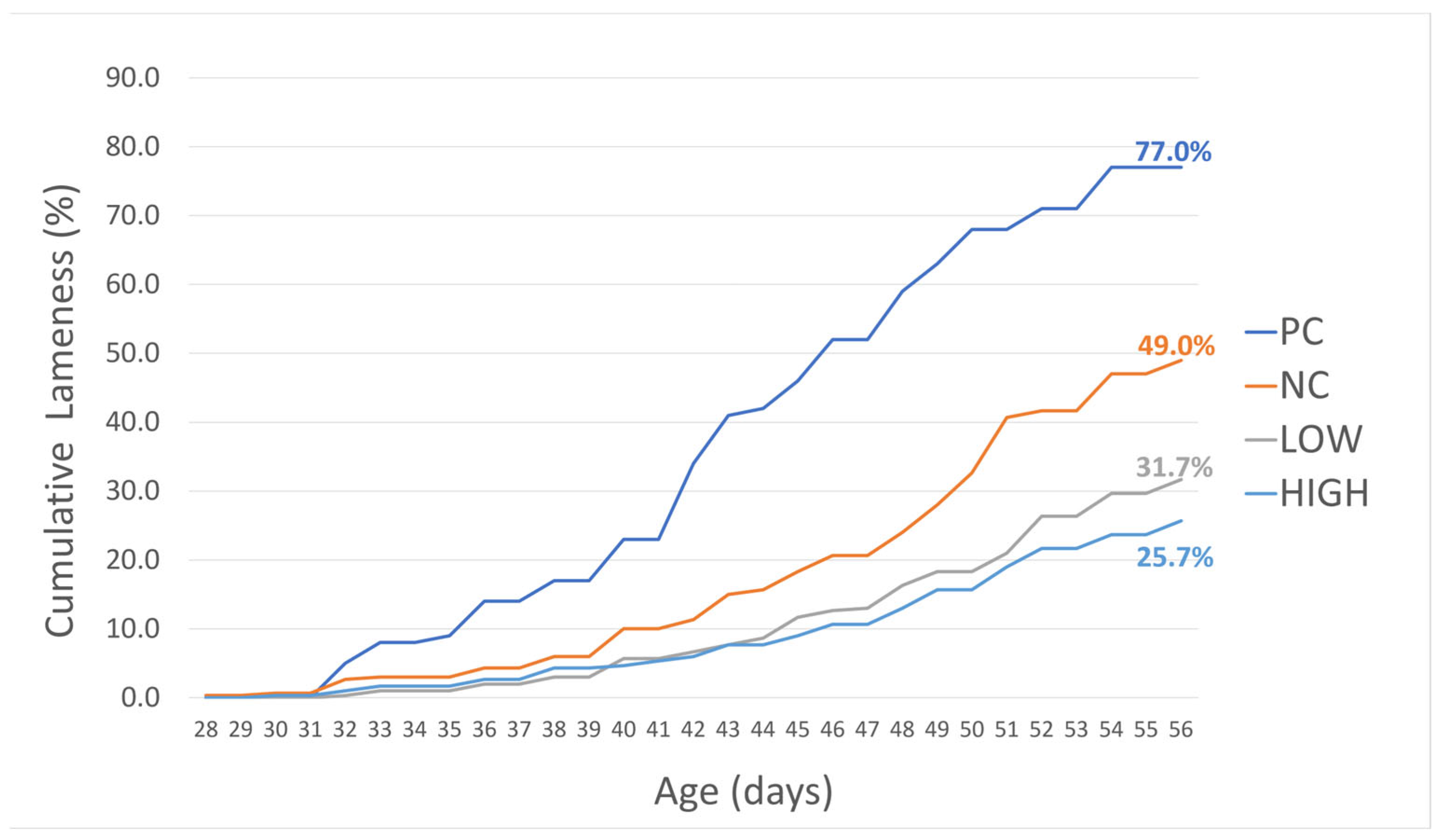

3.1. Cumulative Lameness Incidence

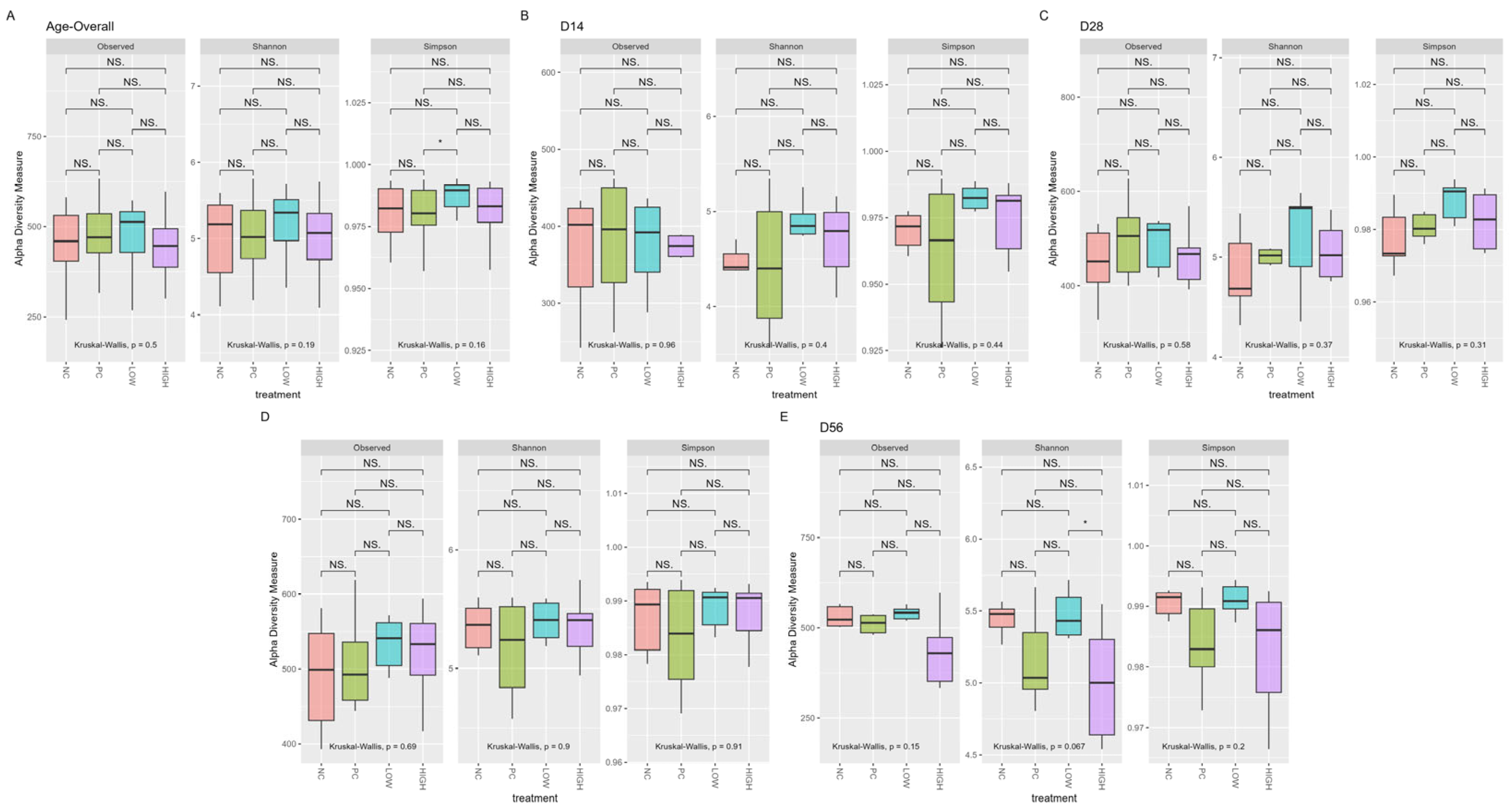

3.2. Alpha Diversity

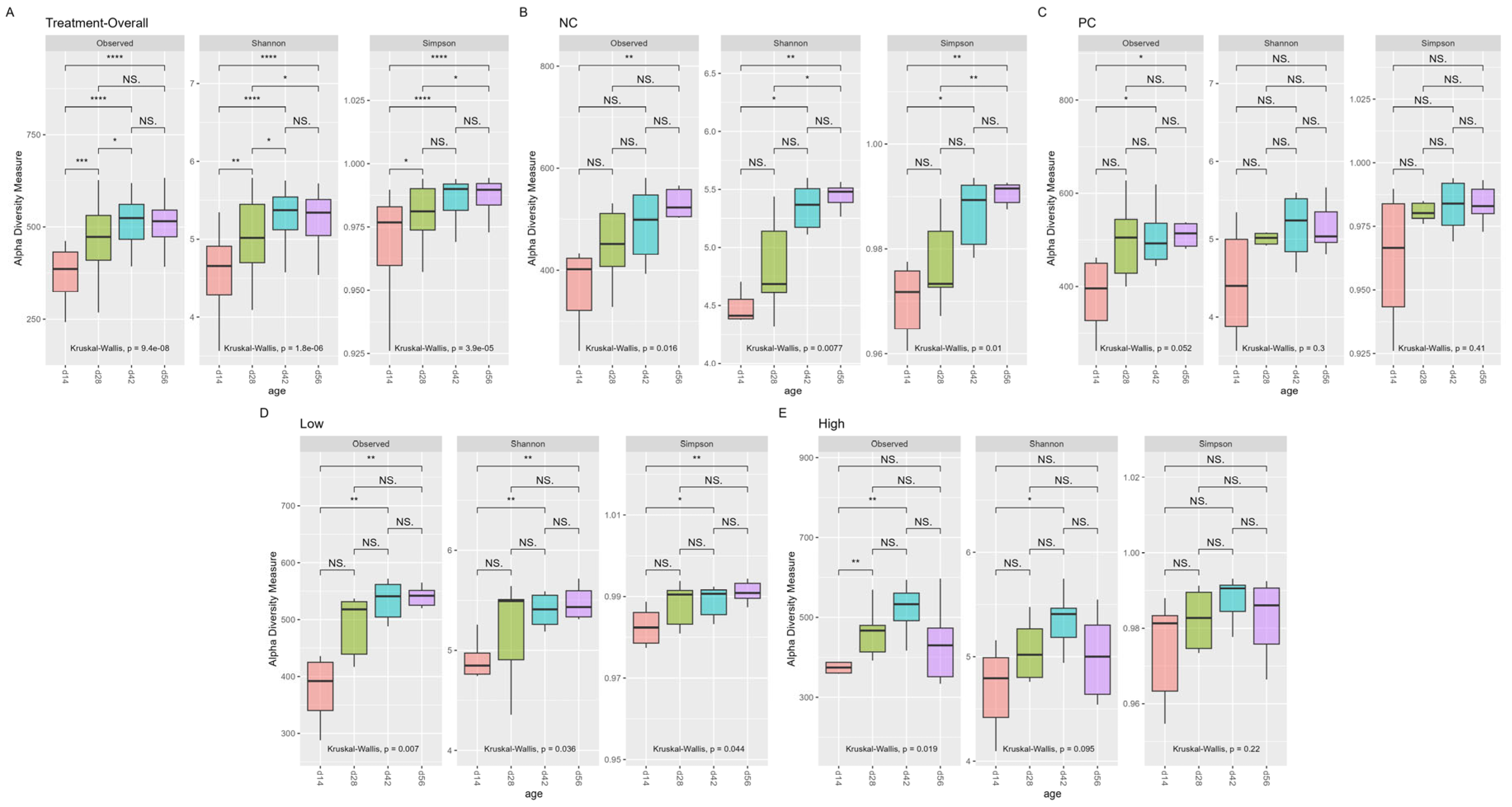

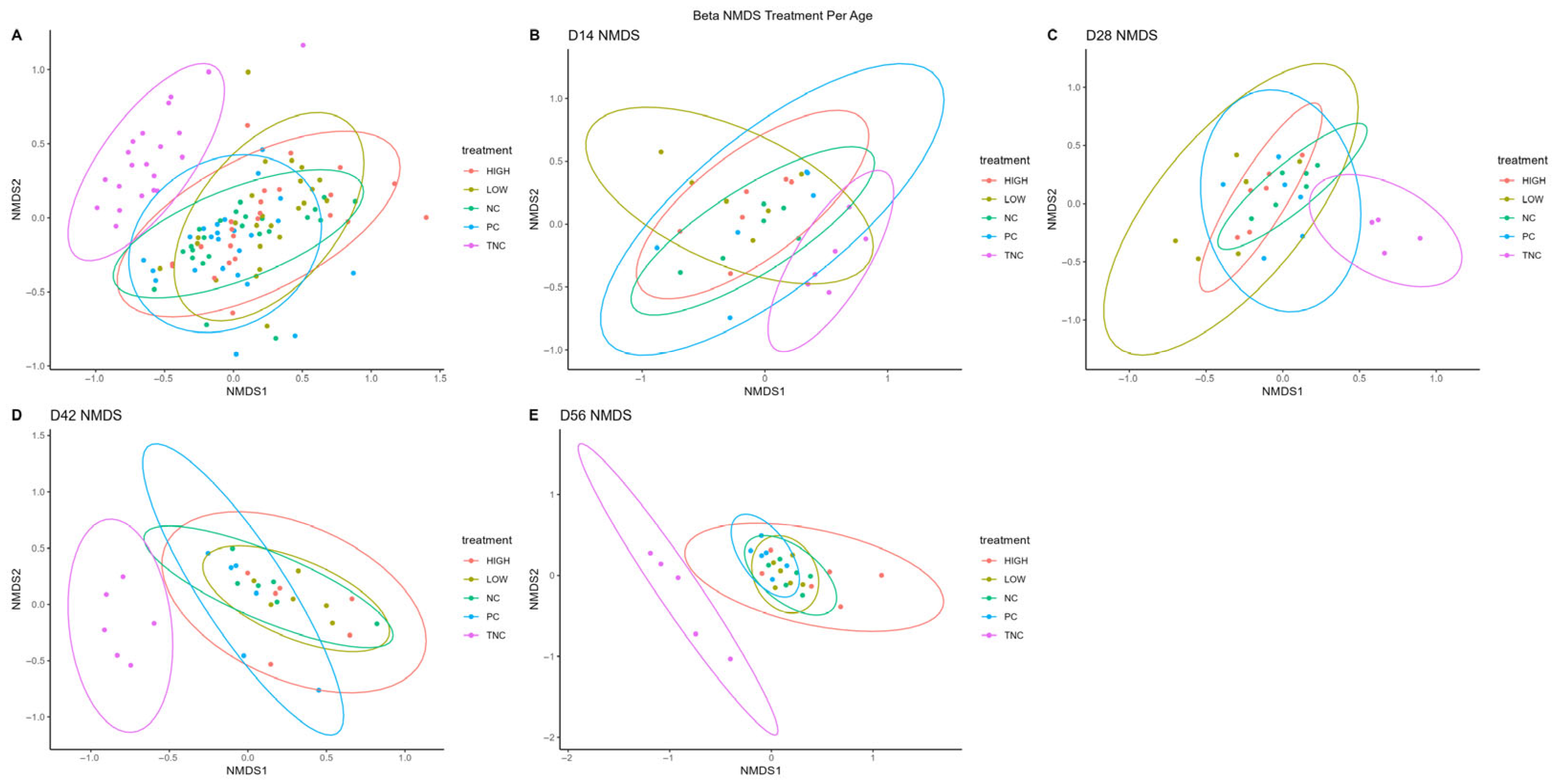

3.3. Βeta Diversity

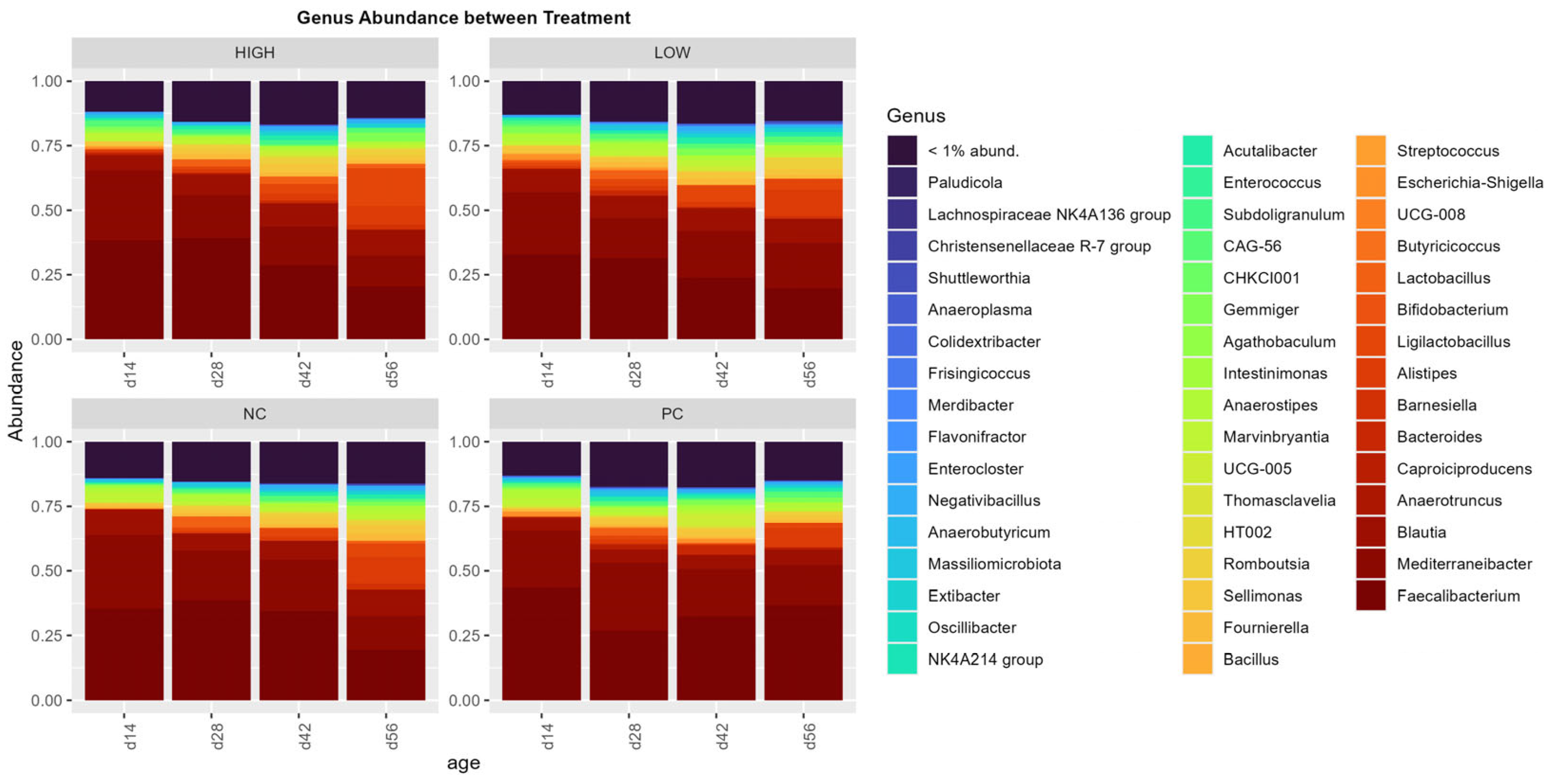

3.4. ASV Relative Abundance

4. Discussion

4.1. Bacterial Community Diversity

4.2. Limitations, Considerations, and Future Suggestions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BCO | Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis |

| PC | Positive Control |

| NC | Negative Control |

| GIT | Gastrointestinal Tract |

References

- National Chicken Council. Broiler Chicken Industry Key Facts 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.nationalchickencouncil.org/about-the-industry/statistics/broiler-chicken-industry-key-facts/ (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- National Chicken Council Per Capita Consumption of Poultry and Livestock, 1965 to Forecast 2022, in Pounds. 2021. Available online: https://www.nationalchickencouncil.org/about-the-industry/statistics/per-capita-consumption-of-poultry-and-livestock-1965-to-estimated-2012-in-pounds/ (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- Vukina, T. Vertical integration and contracting in the US poultry sector. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2001, 32, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- The University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture. Beef Cattle: Economics and Marketing. Available online: https://utbeef.tennessee.edu/beef-cattle-economics-and-marketing/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Brothers, D. New Farmer’s Guide to the Commercial Broiler Industry: Poultry Husbandry & Biosecurity Basics. Alabama Cooperative Extension System. 2022. Available online: https://www.aces.edu/blog/topics/farm-management/new-farmers-guide-to-the-commercial-broiler-industry-poultry-husbandry-biosecurity-basics/ (accessed on 10 June 2024).

- APHIS. Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI)—Depopulation and Disposal for Birds in Your HPAI-Infected Flock; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Poultry Depopulation Guide & Decision Tree 2021. Available online: https://aaap.memberclicks.net/assets/Positions/2020_Poultry_Depopulation%20Guide%20FINAL%20%202-11-21.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Yanai, T.; Abo-Samaha, M.I.; El-Kazaz, S.E.; Tohamy, H.G. Effect of stocking density on productive performance, behaviour, and histopathology of the lymphoid organs in broiler chickens. Eur. Poult. Sci. 2018, 82, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shynkaruk, T.; Long, K.; LeBlanc, C.; Schwean-Lardner, K. Impact of stocking density on the welfare and productivity of broiler chickens reared to 34 d of age. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2023, 32, 100344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, N.; Kock, R.; Zumla, A.; Lee, S.S. Consequences and global risks of highly pathogenic avian influenza outbreaks in poultry in the United Kingdom. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 129, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Aarnink, A.J.A.; Cambra-Lopez, M.; Fabri, T. Viral shedding and emission of airborne infectious bursal disease virus from a broiler room. Br. Poult. Sci. 2013, 54, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adell, E.; Calvet, S.; Pérez-Bonilla, A.; Jiménez-Belenguer, A.; García, J.; Herrera, J.; Cambra-López, M. Air disinfection in laying hen houses: Effect on airborne microorganisms with focus on Mycoplasma gallisepticum. Biosyst. Eng. 2015, 129, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolaia, V.; Espinosa-Gongora, C.; Guardabassi, L. Human health risks associated with antimicrobial-resistant enterococci and Staphylococcus aureus on poultry meat. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016, 22, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Różańska, H.; Lewtak-Piłat, A.; Kubajka, M.; Weiner, M. Occurrence of Enterococci in Mastitic Cow’s Milk and their Antimicrobial Resistance. J. Vet. Res. 2019, 63, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tips for “All In/All Out” Production. 2020. Available online: https://www.biosecuritynovascotia.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2020/03/Biosecurity-Livestock-all-in-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Alaqil, A.A.; Abbas, A.O.; El-Beltagi, H.S.; El-Atty, H.K.A.; Mehaisen, G.M.K.; Moustafa, E.S. Dietary Supplementation of Probiotic Lactobacillus acidophilus Modulates Cholesterol Levels, Immune Response, and Productive Performance of Laying Hens. Animals 2020, 10, 1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrubaye, A.A.K.; Ekesi, N.S.; Hasan, A.; Elkins, E.; Ojha, S.; Zaki, S.; Dridi, S.; Wideman, R.F.; Rebollo, M.A.; Rhoads, D.D. Chondronecrosis with osteomyelitis in broilers: Further defining lameness-inducing models with wire or litter flooring to evaluate protection with organic trace minerals. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 5422–5429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.M.A.; Seidavi, A.; Dadashbeiki, M.; Kilonzo-Nthenge, A.; Nahashon, S.; Laudadio, V.; Tufarelli, V. Effect of a synbiotic (Biomin®IMBO) on growth performance traits of broiler chickens. Arch. Fur Geflugelkd 2015, 79, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nairn, M.; Watson, A. Leg weakness of poultry-a clinical and pathological characterisation. Aust. Vet. J. 1972, 48, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Braga, J.F.V.; Silva, C.C.; de Paula Ferreira Teixeira, M.; da Silva Martins, N.R.; Ecco, R. Vertebral osteomyelitis associated with single and mixed bacterial infection in broilers. Avian Pathol. 2016, 45, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinev, I. Clinical and morphological investigations on the prevalence of lameness associated with femoral head necrosis in broilers. Br. Poult. Sci. 2009, 50, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekesi, N.S.; Dolka, B.; Alrubaye, A.A.K.; Rhoads, D.D. Analysis of genomes of bacterial isolates from lameness outbreaks in broilers. Poult. Sci. 2021, 100, 101148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalker, M.J.; Brash, M.L.; Weisz, A.; Ouckama, R.M.; Slavic, D. Arthritis and osteomyelitis associated with Enterococcus cecorum infection in broiler and broiler breeder chickens in Ontario, Canada. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2010, 22, 643–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wideman, R.F., Jr. Bacterial chondronecrosis with osteomyelitis and lameness in broilers: A review. Poult. Sci. 2016, 95, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferver, A.; Greene, E.; Wideman, R.; Dridi, S. Evidence of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Bacterial Chondronecrosis With Osteomyelitis–Affected Broilers. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 640901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramser, A.; Greene, E.; Alrubaye, A.A.K.; Wideman, R.; Dridi, S. Role of autophagy machinery dysregulation in bacterial chondronecrosis with osteomyelitis. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 101750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramser, A.; Greene, E.; Wideman, R.; Dridi, S. Local and Systemic Cytokine, Chemokine, and FGF Profile in Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis (BCO)-Affected Broilers. Cells 2021, 10, 3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, K.; Asnayanti, A.; Do, A.D.T.; Perera, R.; Al-Mitib, L.; Shwani, A.; Rebollo, M.A.; Kidd, M.T.; Alrubaye, A.A.K. Identifying Dietary Timing of Organic Trace Minerals to Reduce the Incidence of Osteomyelitis Lameness in Broiler Chickens Using the Aerosol Transmission Model. Animals 2024, 14, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asnayanti, A.; Alharbi, K.; Do, A.D.T.; Al-Mitib, L.; Bühler, K.; Van der Klis, J.D.; Gonzalez, J.; Kidd, M.T.; Alrubaye, A.A.K. Early 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-glycosides supplementation: An efficient feeding strategy against bacterial chondronecrosis with osteomyelitis lameness in broilers assessed by using an aerosol transmission model. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2024, 33, 100440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, R.; Alharbi, K.; Hasan, A.; Asnayanti, A.; Do, A.; Shwani, A.; Murugesan, R.; Ramirez, S.; Kidd, M.; Alrubaye, A.A.K. Evaluating the Impact of the PoultryStar®Bro Probiotic on the Incidence of Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis Using the Aerosol Transmission Challenge Model. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asnayanti, A.; Do, A.D.T.; Alharbi, K.; Alrubaye, A. Inducing experimental bacterial chondronecrosis with osteomyelitis lameness in broiler chickens using aerosol transmission model. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wideman, R., Jr.; Hamal, K.; Stark, J.; Blankenship, J.; Lester, H.; Mitchell, K.; Lorenzoni, G.; Pevzner, I. A wire-flooring model for inducing lameness in broilers: Evaluation of probiotics as a prophylactic treatment. Poult. Sci. 2012, 91, 870–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assumpcao, A.L.F.V.; Arsi, K.; Asnayanti, A.; Alharbi, K.S.; Do, A.D.T.; Read, Q.D.; Perera, R.; Shwani, A.; Hasan, A.; Pillai, S.D.; et al. Electron-Beam-Killed Staphylococcus Vaccine Reduced Lameness in Broiler Chickens. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Microbiome Project, C. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome. Nature 2012, 486, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengmark, S. Gut microbiota, immune development and function. Pharmacol. Res. 2013, 69, 87–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacson, R.; Kim, H.B. The intestinal microbiome of the pig. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2012, 13, 100–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Yu, Z. Intestinal microbiome of poultry and its interaction with host and diet. Gut Microbes 2014, 5, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleton, J. The Gut-Brain Axis: Influence of Microbiota on Mood and Mental Health. Integr. Med. 2018, 17, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.-X.; Chen, X.-Y.; Wang, J.-Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oakley, B.B.; Lillehoj, H.S.; Kogut, M.H.; Kim, W.K.; Maurer, J.J.; Pedroso, A.; Lee, M.D.; Collett, S.R.; Johnson, T.J.; Cox, N.A. The chicken gastrointestinal microbiome. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2014, 360, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducatelle, R.; Goossens, E.; Eeckhaut, V.; Van Immerseel, F. Poultry gut health and beyond. Anim. Nutr. 2023, 13, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, R.K.; Jiang, T.; Wideman, R.F.; Lohrmann, T.; Kwon, Y.M. Microbiota Analysis of Chickens Raised Under Stressed Conditions. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 482637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, K.; Dang Trieu Do, A.; Alqahtani, A.; Perera, R.; Thomas, A.; Meuter, A.; Alrubaye, A.A.K. Assessing the Impact of Spraying an E. faecium Probiotic at Hatch and Supplementing Feed with a Triple-Strain Bacillus-Based Additive on BCO Lameness Incidence in Broiler Chickens. Animals 2025, 15, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, A.D.T.; Anthney, A.; Alharbi, K.; Asnayanti, A.; Meuter, A.; Alrubaye, A.A.K. Assessing the Impact of Spraying an Enterococcus faecium-Based Probiotic on Day-Old Broiler Chicks at Hatch on the Incidence of Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis Lameness Using a Staphylococcus Challenge Model. Animals 2024, 14, 1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, A.D.T.; Lozano, A.; Van Laar, T.A.; Mero, R.; Lopez, C.; Hisasaga, C.; Lopez, R.; Franco, M.; Celeste, R.; Tarrant, K.J. Evaluating microbiome patterns, microbial species, and leg health associated with reused litter in a commercial broiler barn. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2024, 33, 100490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.S.G.; Blanchet, F.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.; O’Hara, R.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.; Szoecs, E.; Wagner, H.; et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. 2025. Available online: https://vegandevs.github.io/vegan/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Lahti, L.S.S. microbiome R Package. 2012–2019. Available online: https://microbiome.github.io/tutorials/ (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.A.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Hack, M.E.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Salem, H.M.; El-Tahan, A.M.; Soliman, M.M.; Youssef, G.B.A.; Taha, A.E.; Soliman, S.M.; Ahmed, A.E.; El-Kott, A.F.; et al. Alternatives to antibiotics for organic poultry production: Types, modes of action and impacts on bird’s health and production. Poult Sci. 2022, 101, 101696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, L.Z.; Ho, Y.W.; Abdullah, N.; Jalaludin, S. Probiotics in poultry: Modes of action. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 1997, 53, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.T.; Zeng, X.F.; Chen, A.G.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, Y.P.; Yang, C.M. Effects of a probiotic, Enterococcus faecium, on growth performance, intestinal morphology, immune response, and cecal microflora in broiler chickens challenged with Escherichia coli K88. Poult. Sci. 2013, 92, 2949–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Sousa, N.; do Couto, M.V.S.; Abe, H.A.; Paixão, P.E.G.; Cordeiro, C.A.M.; Monteiro Lopes, E.; Ready, J.S.; Jesus, G.F.A.; Martins, M.L.; Mouriño, J.L.P.; et al. Effects of an Enterococcus faecium-based probiotic on growth performance and health of Pirarucu, Arapaima gigas. Aquac. Res. 2019, 50, 3720–3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VilÀ, B.; Esteve-Garcia, E.; Brufau, J. Probiotic micro-organisms: 100 years of innovation and efficacy; modes of action. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2010, 66, 369–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wideman, R.F.; Prisby, R.D. Bone Circulatory Disturbances in the Development of Spontaneous Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis: A Translational Model for the Pathogenesis of Femoral Head Necrosis. Front. Endocrinol. 2013, 3, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Mandal, R.K.; Wideman, R.F., Jr.; Khatiwara, A.; Pevzner, I.; Min Kwon, Y. Molecular Survey of Bacterial Communities Associated with Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis (BCO) in Broilers. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, R.K.; Jiang, T.; Al-Rubaye, A.A.; Rhoads, D.D.; Wideman, R.F.; Zhao, J.; Pevzner, I.; Kwon, Y.M. An investigation into blood microbiota and its potential association with Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis (BCO) in Broilers. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Bajaj, B.; Claes, I.J.; Lebeer, S. Functional mechanisms of probiotics. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Food Sci. 2015, 4, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Shaufi, M.A.; Sieo, C.C.; Chong, C.W.; Tan, G.H.; Omar, A.R.; Ho, Y.W. Multiple factorial analysis of growth performance, gut population, lipid profiles, immune responses, intestinal histomorphology, and relative organ weights of Cobb 500 broilers fed a diet supplemented with phage cocktail and probiotics. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 23, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, R.; Havenaar, R.; Huis in’t Veld, J. Intervention strategies: The use of probiotics and competitive exclusion microfloras against contamination with pathogens in pigs and poultry. In Probiotics 2: Applications and Practical Aspects; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; pp. 187–207. [Google Scholar]

- Anthney, A.; Alharbi, K.; Perera, R.; Do, A.D.T.; Asnayanti, A.; Onyema, R.; Reichelt, S.; Meuter, A.; Jesudhasan, P.R.R.; Alrubaye, A.A.K. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Probiotic and Multivalent Vaccination Strategies in Mitigating Bacterial Chondronecrosis with Osteomyelitis Lameness Using a Hybrid Challenge Model. Animals 2025, 15, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madej, J.P.; Graczyk, S.; Bobrek, K.; Bajzert, J.; Gaweł, A. Impact of early posthatch feeding on the immune system and selected hematological, biochemical, and hormonal parameters in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders-Blades, J.L.; Korver, D.R. Effect of hen age and maternal vitamin D source on performance, hatchability, bone mineral density, and progeny in vitro early innate immune function. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 1233–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olfati, A.; Mojtahedin, A.; Sadeghi, T.; Akbari, M.; Martínez-Pastor, F. Comparison of growth performance and immune responses of broiler chicks reared under heat stress, cold stress and thermoneutral conditions. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2018, 16, e0505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danzeisen, J.L.; Kim, H.B.; Isaacson, R.E.; Tu, Z.J.; Johnson, T.J. Modulations of the Chicken Cecal Microbiome and Metagenome in Response to Anticoccidial and Growth Promoter Treatment. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e27949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballou, A.L.; Ali, R.A.; Mendoza, M.A.; Ellis, J.C.; Hassan, H.M.; Croom, W.J.; Koci, M.D. Development of the Chick Microbiome: How Early Exposure Influences Future Microbial Diversity. Front. Vet. Sci. 2016, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoa Rama, E.; Bailey, M.; Kumar, S.; Leone, C.; den Bakker, H.C.; Thippareddi, H.; Singh, M. Characterizing the gut microbiome of broilers raised under conventional and no antibiotics ever practices. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 102832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.-X.; Li, M.-H.; Wang, X.-Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ni, H.-B.; Ma, H.; Liu, R.; Yan, J.-C.; Li, X.-M.; et al. Temporal variability in the diversity, function and resistome landscapes in the gut microbiome of broilers. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 292, 117976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourabedin, M.; Xu, Z.; Baurhoo, B.; Chevaux, E.; Zhao, X. Effects of mannan oligosaccharide and virginiamycin on the cecal microbial community and intestinal morphology of chickens raised under suboptimal conditions. Can. J. Microbiol. 2014, 60, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourabedin, M.; Zhao, X. Prebiotics and gut microbiota in chickens. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2015, 362, fnv122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrigan, A.; Leeuw, M.d.; Penaud-Frézet, S.; Dimova, D.; Murphy, R.A. Phylogenetic and Functional Alterations in Bacterial Community Compositions in Broiler Ceca as a Result of Mannan Oligosaccharide Supplementation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 3460–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grigor’eva, I.N. Gallstone Disease, Obesity and the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio as a Possible Biomarker of Gut Dysbiosis. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finucane, M.M.; Sharpton, T.J.; Laurent, T.J.; Pollard, K.S. A taxonomic signature of obesity in the microbiome? Getting to the guts of the matter. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e84689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, K.; Kassis, A.; Major, G.; Chou, C.J. Is the gut microbiota a new factor contributing to obesity and its metabolic disorders? J. Obes. 2012, 2012, 879151. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, R.; Scharch, C.; Sandvang, D. The link between broiler flock heterogeneity and cecal microbiome composition. Anim. Microbiome 2021, 3, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, Y.; Ansari, A.R.; Akhtar, M.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, R.; Cui, L.; Nafady, A.A.; Elokil, A.A.; Abdel-Kafy, E.-S.M.; et al. Caecal microbiota could effectively increase chicken growth performance by regulating fat metabolism. Microb. Biotechnol. 2022, 15, 844–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaheen, S.; Kim, S.-W.; Haley, B.J.; Van Kessel, J.A.S.; Biswas, D. Alternative Growth Promoters Modulate Broiler Gut Microbiome and Enhance Body Weight Gain. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Xu, M.; Wang, G.; Feng, J.; Zhang, M. Effects of different photoperiods on melatonin level, cecal microbiota and breast muscle morphology of broiler chickens. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1504264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Nesengani, L.; Gong, Y.; Yang, Y.; Lu, W. 16S rRNA gene sequencing reveals effects of photoperiod on cecal microbiota of broiler roosters. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.U.; Idrus, Z.; Meng, G.Y.; Awad, E.A.; Soleimani Farjam, A. Gut microbiota and transportation stress response affected by tryptophan supplementation in broiler chickens. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2018, 17, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Santisteban, M.M.; Rodriguez, V.; Li, E.; Ahmari, N.; Carvajal, J.M.; Zadeh, M.; Gong, M.; Qi, Y.; Zubcevic, J.; et al. Gut Dysbiosis Is Linked to Hypertension. Hypertension 2015, 65, 1331–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population | Treatment | Pen Type |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Control—PC | None | Wire |

| Negative Control—NC | None | Litter |

| Probiotic Spray—LOW | E. faecium 669 @ 2 × 109 CFU/bird on d0 | Litter |

| Probiotic Spray + Diet—HIGH | E. faecium 669 @ 2 × 109 CFU/bird on d0 + B. amyloliquefaciens 516/B. subtilis 597/B. subtilis 600 @ 492.1 mg/kg feed for 56 d | Litter |

| p-Value | NC | LOW | HIGH |

|---|---|---|---|

| PC † | 0.0036 * | 0.0037 * | 0.0086 * |

| NC | <0.0004 * | <0.0001 * | |

| LOW | 0.0133 * |

| Treatment | Observed | Shannon | Simpson |

|---|---|---|---|

| NC | 0.016 | 0.0077 | 0.01 |

| PC | NS | NS | NS |

| LOW | 0.007 | 0.036 | 0.044 |

| HIGH | 0.019 | NS | NS |

| Treatment | PERMANOVA (R2; p) | ANOSIM (R; p) | Dispersion (p) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 0.174; 0.001 | 0.299; 0.0001 | 0.026 |

| NC | 0.302; 0.001 | 0.383; 0.0001 | NS |

| PC | 0.218; 0.008 | 0.202; 0.002 | NS |

| LOW | 0.250; 0.001 | 0.323; 0.0002 | 0.004 |

| HIGH | 0.291; 0.001 | 0.347; 0.0002 | NS |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Do, A.D.T.; Alharbi, K.; Perera, R.; Asnayanti, A.; Alrubaye, A. Preliminary Investigation of Cecal Microbiota in Experimental Broilers Reared Under the Aerosol Transmission Lameness Induction Model. Animals 2025, 15, 3641. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243641

Do ADT, Alharbi K, Perera R, Asnayanti A, Alrubaye A. Preliminary Investigation of Cecal Microbiota in Experimental Broilers Reared Under the Aerosol Transmission Lameness Induction Model. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3641. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243641

Chicago/Turabian StyleDo, Anh Dang Trieu, Khawla Alharbi, Ruvindu Perera, Andi Asnayanti, and Adnan Alrubaye. 2025. "Preliminary Investigation of Cecal Microbiota in Experimental Broilers Reared Under the Aerosol Transmission Lameness Induction Model" Animals 15, no. 24: 3641. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243641

APA StyleDo, A. D. T., Alharbi, K., Perera, R., Asnayanti, A., & Alrubaye, A. (2025). Preliminary Investigation of Cecal Microbiota in Experimental Broilers Reared Under the Aerosol Transmission Lameness Induction Model. Animals, 15(24), 3641. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243641