Assessing the Hibernation Ecology of the Endangered Amphibian, Pelophylax chosenicus Using PIT Tagging Method

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site and Period

2.2. PIT Tagging and Monitoring

2.2.1. PIT Tag Implantation

2.2.2. Monitoring

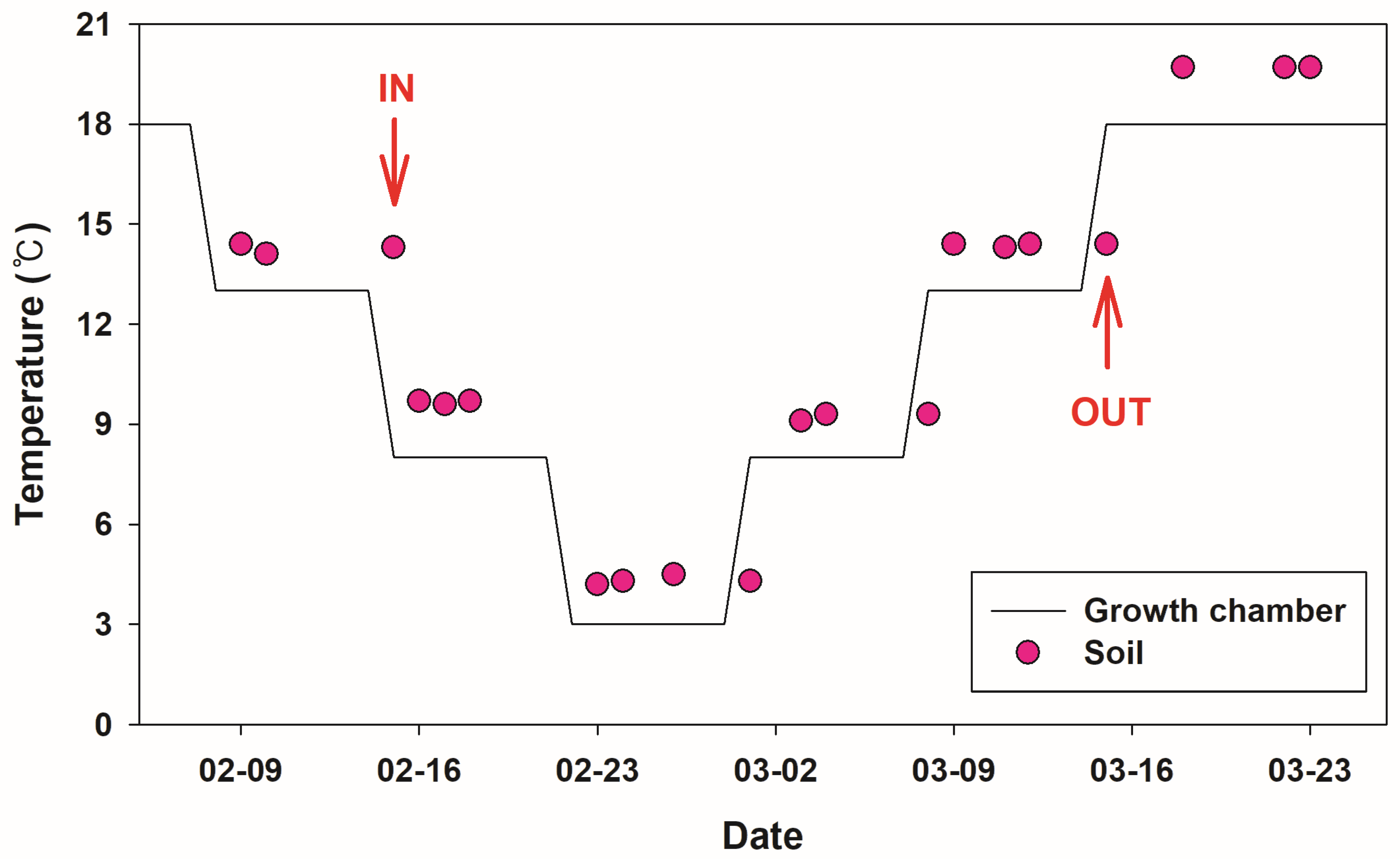

2.3. Hibernation Temperature Experiments

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

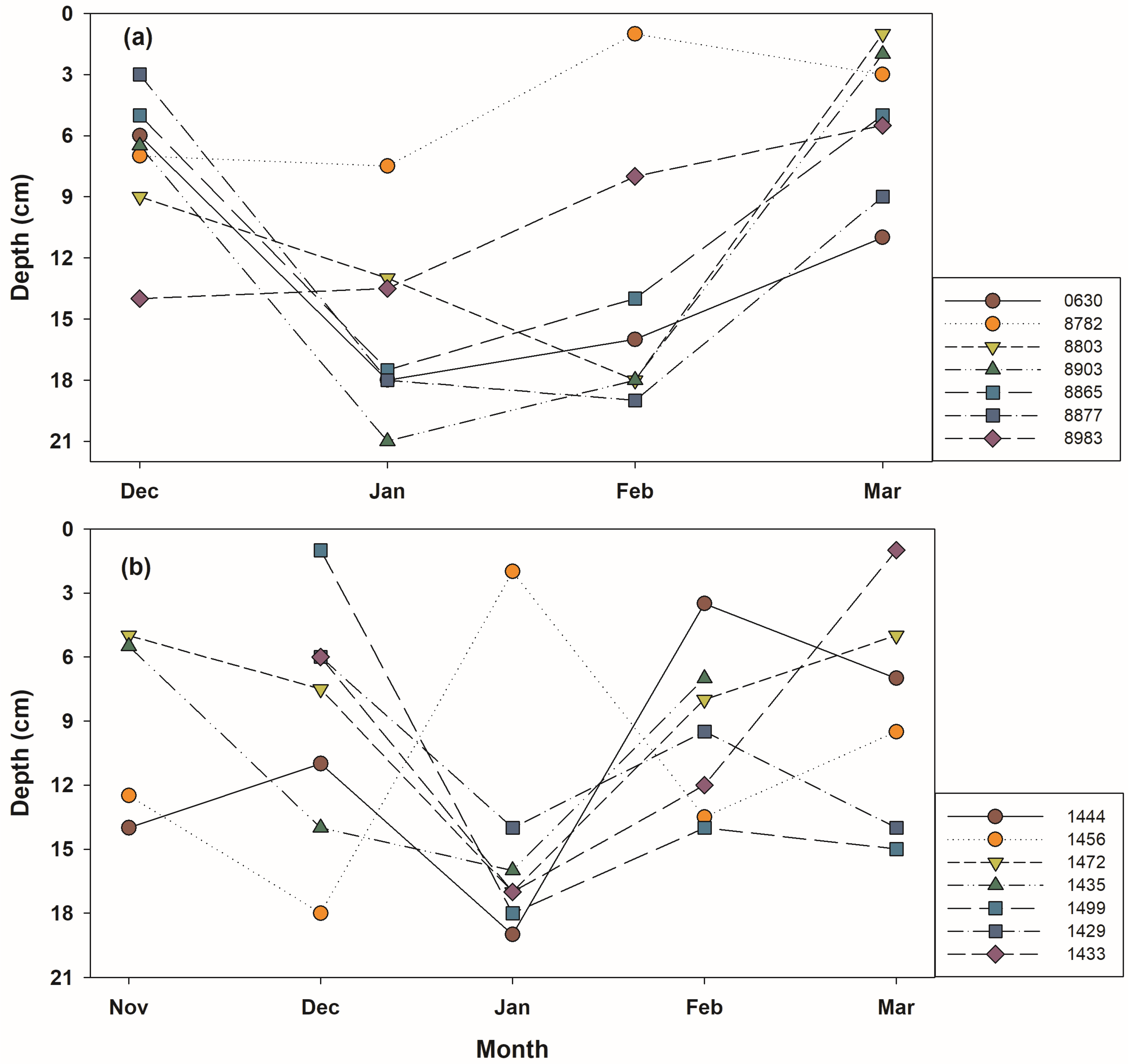

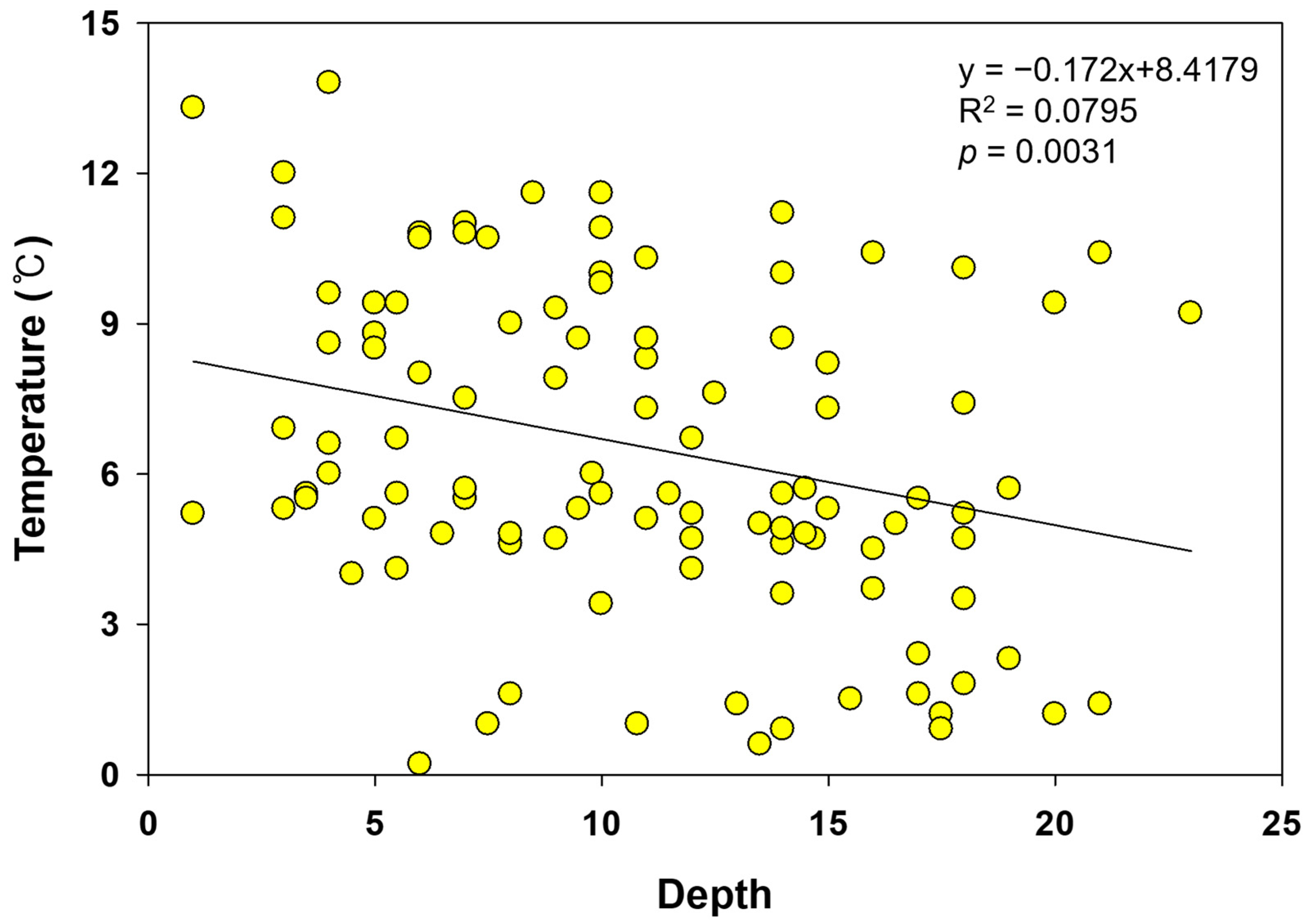

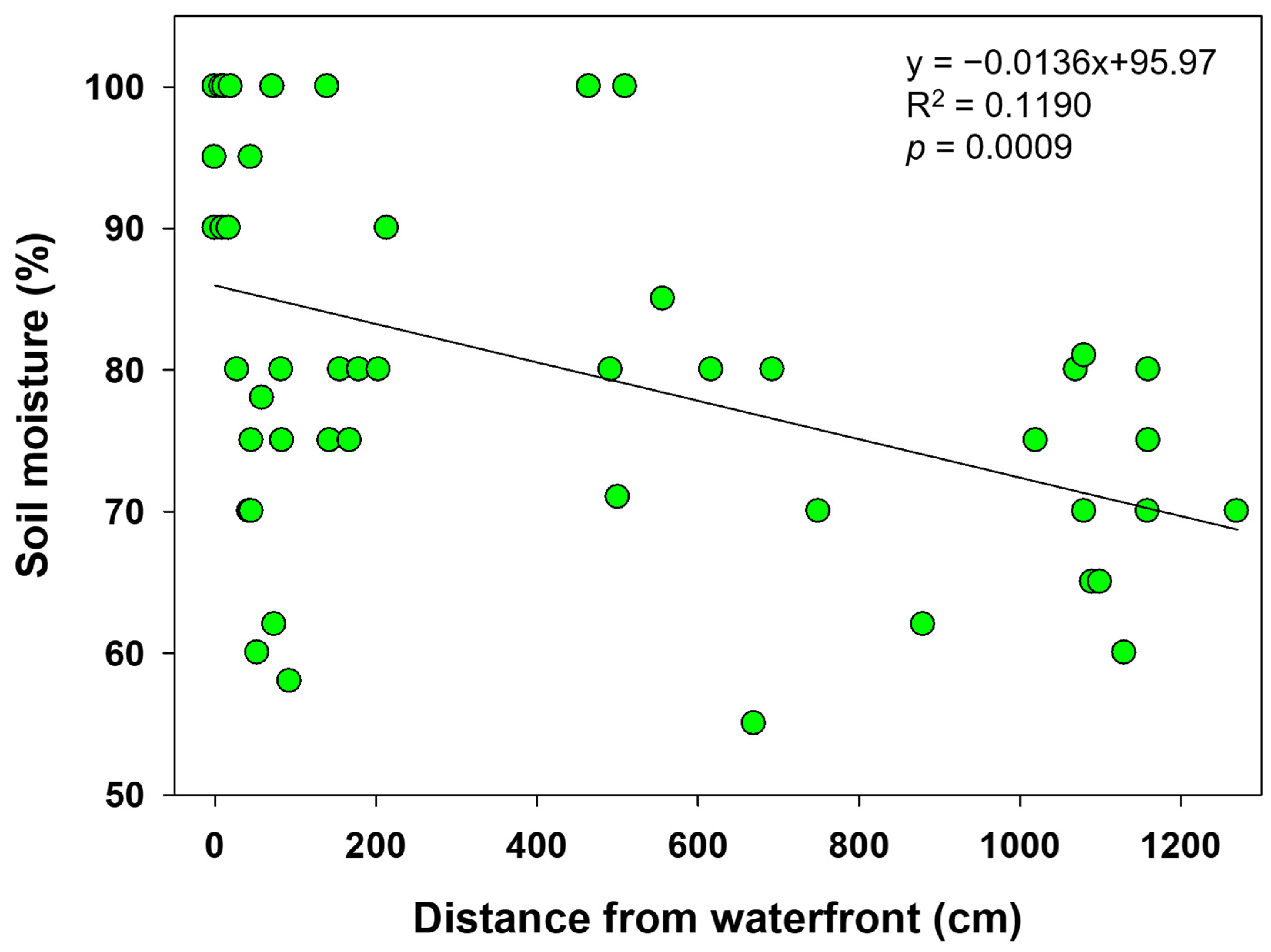

3.1. Characteristics of Hibernation Sites

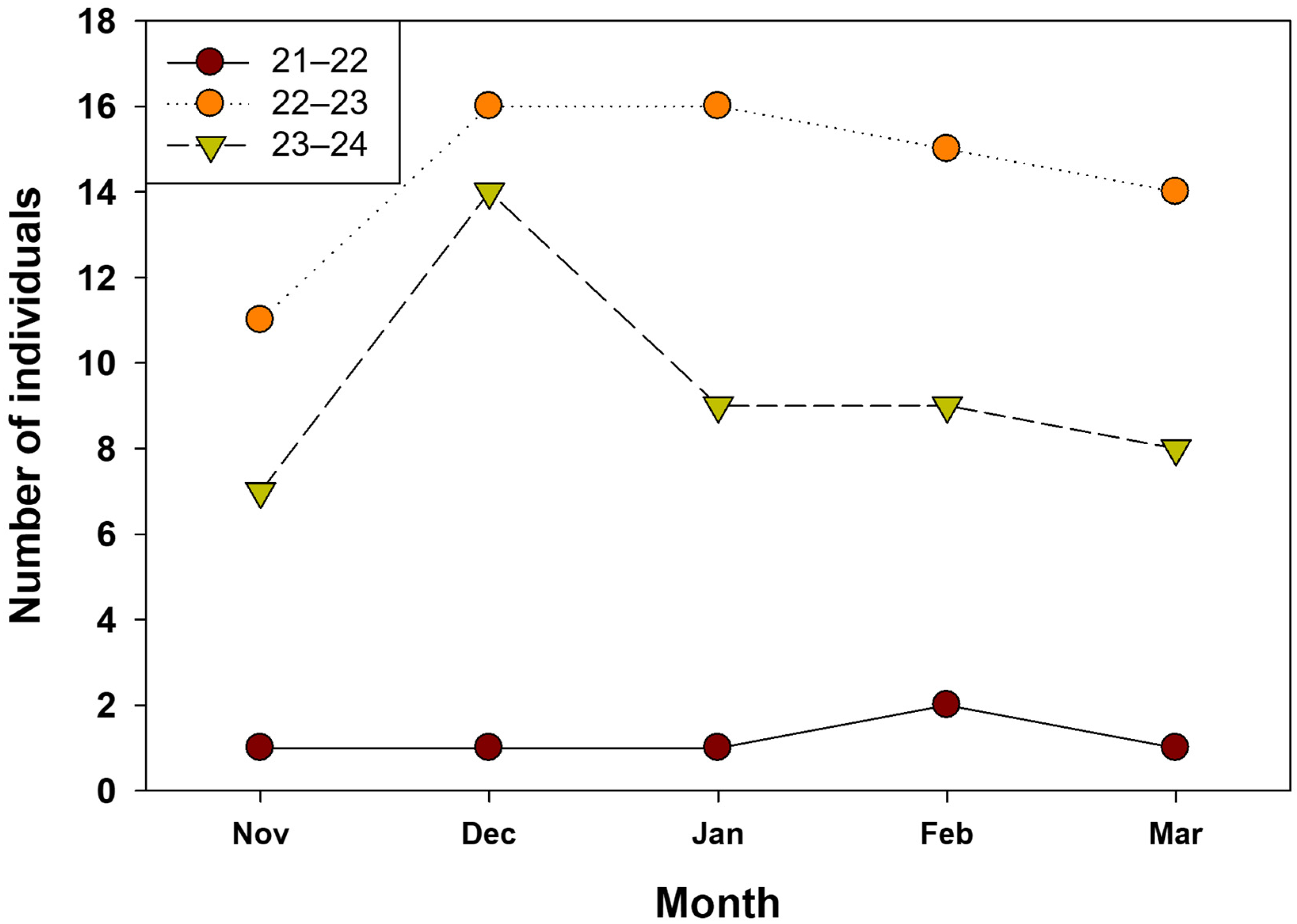

3.2. Hibernation and Emergence from Hibernation

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holenweg, A.K.; Reyer, H.U. Hibernation behavior of Rana lessonae and R. esculenta in their natural habitat. Oecologia 2000, 123, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tattersall, G.J.; Ultsch, G.R. Physiological ecology of aquatic overwintering in ranid frogs. Biol. Rev. 2008, 83, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinsch, U. Sommer-und Winterquartiere der Herpetofauna in Auskiesungen. Salamandra 1989, 25, 104–108. [Google Scholar]

- Denton, J.S.; Beebee, T.J.C. Summer and winter refugia of natterjacks (Bufo calamita) and common toads (Bufo bufo) in Britain. Herpetol. J. 1993, 3, 90–94. [Google Scholar]

- Storey, K.B.; Storey, J.M. Physiology, biochemistry, and molecular biology of vertebrate freeze tolerance: The wood frog. In Life in the Frozen State; Fuller, B., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004; pp. 243–274. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H.; Park, D.S. The Encyclopedia of Korean Amphibians; Nature and Ecology: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2016; 248p. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Hamer, A.J.; McDonnell, M.J. Amphibian ecology and conservation in the urbanizing world: A review. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 2137–2147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morhardt, J.E.; Bisher, D.; Handlin, C.I.; Mulder, S.D. A portable system for reading large PIT tags from wild trout. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2000, 20, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Santos, T.; Haro, A.; Walk, S. A passive integrated transponder (PIT) tag system for monitoring fishways. Fish. Res. 1996, 28, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarestrup, K.; Lucas, M.C.; Hansen, J.A. Efficiency of a nature-like bypass channel for sea trout (Salmo trutta) ascending a small Danish stream studied by PIT telemetry. Ecol. Freshw. Fish 2003, 12, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, K.; Nakashima, N.; Moriyama, T.; Mori, A.; Watabe, K.; Tamura, T. Development of methods to detect hibernation sites of Tokyo Daruma pond frog (Pelophylax porosus porosus) using the PIT tag system. Ecol. Civ. Eng. 2019, 22, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.S.; Feuka, A.B.; Muths, E.; Hardy, B.M.; Bailey, L.L. Trade-offs in initial and long-term handling efficiency of PIT-tag and photographic identification methods. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 130, 108110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, M.A.; Guyer, C.; Juterbock, E.J.; Alford, R.A. Techniques for marking amphibians. In Measuring and Monitoring Biological Diversity: Standard Methods for Amphibians; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 277–284. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, W.J.; Andrews, K.M. PIT Tagging: Simple technology at its best. BioScience 2004, 54, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Lee, H.J.; Ra, N.Y.; Kim, J.K.; Eom, J.H.; Park, D.S. Application of PIT tag and radio telemetry research methods for the effective management of reptiles in Korea National Parks. Kor. J. Environ. Biol. 2009, 27, 146–154. [Google Scholar]

- Emerson, S.B. Burrowing in frogs. J. Herpetol. 1976, 149, 437–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, C.B. External and internal control of patterns of feeding, growth, and gonadal function in a temperate zone anuran, the toad Bufo bufo. J. Zool. 1986, 210, 211–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calatayud, N.E.; Langhorne, C.J.; Mullen, A.C.; Williams, C.L.; Smith, T.; Bullock, L.; Willard, S.T. A hormone priming regimen and hibernation affect oviposition in the boreal toad (Anaxyrus boreas boreas). Theriogenology 2015, 84, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santana, F.; Swaisgood, R.; Lemm, J.; Fisher, R.; Clark, R. Chilled frogs are hot: Hibernation and reproduction of the Endangered mountain yellow-legged frog Rana muscosa. Endanger. Species Res. 2015, 27, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calatayud, N.E.; Hammond, T.T.; Gardner, N.R.; Curtis, M.J.; Swaisgood, R.R.; Shier, D.M. Benefits of overwintering in the conservation breeding and translocation of a critically endangered amphibian. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2021, 3, e341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, S.; Park, D.S.; Sung, H.C.; Lee, J.H.; Park, S.R. Skeletochronological age determination and comparative demographic analysis of two populations of the Gold-spotted Pond Frog (Rana chosenica). J. Ecol. Field Biol. 2007, 30, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.J.; Kang, S.W.; Kwon, H.W.; Bae, Y.S. The Initial Growth and Frequency of Occurrence of Gold-Spotted Pond Frogs (Pelophylax chosenicus) in Artificially Created Alternative Habitats. J. Environ. Sci. Int. 2025, 34, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arısoy, A.G.; Başkale, E. Body size, age structure and survival rates in two populations of the Beyşehir frog Pelophylax caralitanus. Herpetozoa 2019, 32, e35772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ra, N.Y.; Sung, H.C.; Cheong, S.; Lee, J.H.; Eom, J.; Park, D. Habitat Use and Home Range of the Endangered Gold-Spotted Pond Frog (Rana chosenica). Zool. Sci. 2008, 25, 894–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, T.; Nozaki, N.; Yoshida, M.; Kanou, C.; Fukuda, Y. Observation hibernation of daruma pond frog, Rana porosa brevipoda reared in outdoor tanks. Hyogo Freshw. Biol. 2010, 61, 189–194. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima, N.; Moriyama, T.; Motegi, M.; Mori, A.; Watabe, K. Underground behavior of overwintering Tokyo daruma pond frogs in early spring. Paddy Water Environ. 2021, 19, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.G.; Ra, N.Y.; Jang, Y.S.; Woo, S.H.; Koo, K.S.; Jang, M.H. Comparison of Movement Distance and Home Range Size of Gold-Spotted Pond Frog (Pelophylax chosenicus) between Rice Paddy and Ecological Park. Ecol. Resil. Infrastruct. 2019, 6, 200–207. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Jin, C.; Llusia, D.; Li, Y. Temperature-induced shifts in hibernation behavior in experimental amphibian populations. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anholt, B.R.; Hotz, H.; Guex, G.D.; Semlitsch, R.D. Overwinter survival of Rana lessonae and its hemiclonal associate Rana esculenta. Ecology 2003, 84, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üveges, B.; Mahr, K.; Szederkényi, M.; Bókony, V.; Hoi, H.; Hettyey, A. Experimental evidence for beneficial effects of projected climate change on hibernating amphibians. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCaffery, R.M.; Maxell, B.A. Decreased winter severity increases viability of a montane frog population. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 8644–8649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, J.H.; Rittenhouse, T.A.G. Snow cover and late fall movement influence wood frog survival during an unusually cold winter. Oecologia 2016, 181, 635–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiskopf, S.R.; Shiklomanov, A.N.; Thompson, L.; Wheedleton, S.; Campbell Grant, E.H. Winter severity affects occupancy of spring- and summer-breeding anurans across the eastern United States. Divers. Distrib. 2022, 28, 2187–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | 1st (n: 6) | 2nd (n: 61) | 3rd (n: 47) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nov (n: 1) | Dec (n: 1) | Jan (n: 1) | Feb (n: 2) | Mar (n: 1) | Nov (n: 0) | Dec (n: 16) | Jan (n: 16) | Feb (n: 15) | Mar (n: 14) | Nov (n: 7) | Dec (n: 14) | Jan (n: 9) | Feb (n: 9) | Mar (n: 8) | |

| SVL (mm) | 38.7 | 55.5 | 58.0 | 46.7 ± 7.6 | 53.1 | - | 43.7 ± 8.6 | 46.4 ± 7.8 | 46.6 ± 8.8 | 49.2 ± 8.3 | 46.4 ± 7.2 | 43.8 ± 8.3 | 44.2 ± 7.1 | 42.4 ± 2.8 | 42.9 ± 3.7 |

| 49.8 ± 7.8 (38.7~58.0) | 46.4 ± 8.6 (32.5~64.9) | 43.8 ± 6.6 (29.3~61.8) | |||||||||||||

| BW (g) | 7.7 | 22.4 | 23.4 | 14.8 ± 7.4 | 21.8 | - | 13.8 ± 9.5 | 15.1 ± 9.2 | 15.6 ± 9.6 | 18.1 ± 10.5 | 14.2 ± 7.2 | 12.7 ± 8.3 | 13.2 ± 7.6 | 11.1 ± 2.6 | 10.1 ± 2.0 |

| 17.5 ± 7.0 (7.4~23.4) | 15.6 ± 9.8 (5.2~40.0) | 12.3 ± 6.6 (3.5~33.1) | |||||||||||||

| Soil depth (cm) | 5.0 | 6.0 | 18.0 | 11.0 ± 5.0 | 11.0 | - | 9.9 ± 4.4 | 11.7 ± 5.3 | 12.5 ± 4.9 | 8.8 ± 6.9 | 10.3 ± 3.7 | 11.6 ± 5.3 | 15.8 ± 4.5 | 9.1 ± 3.7 | 10.2 ± 3.1 |

| 10.3 ± 5.1 (5.0~18.0) | 10.7 ± 5.6 (1.0~23.0) | 11.5 ± 4.9 (3.5~21.0) | |||||||||||||

| Soil temperature (°C) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5.9 ± 1.1 | 2.1 ± 1.7 | 4.9 ± 0.8 | 10.1 ± 1.7 | 7.9 ± 0.7 | 10.8 ± 0.4 | 3.5 ± 1.7 | 5.3 ± 0.3 | 9.5 ± 0.8 |

| 5.6 ± 3.2 (0.2~13.8) | 7.7 ± 3.0 (1.2~11.6) | ||||||||||||||

| Soil pH | - | - | - | - | - | - | 6.0 ± 0.3 | 6.3 ± 0.2 | 6.2 ± 0.2 | 6.2 ± 0.4 | 6.0 ± 0.2 | 6.4 ± 0.2 | 6.6 ± 0.3 | 6.5 ± 0.1 | 6.4 ± 0.3 |

| 6.2 ± 0.3 (5.5~6.8) | 6.4 ± 0.3 (5.8~7.0) | ||||||||||||||

| Soil moisture (%) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 87.4 ± 11.6 | 78.8 ± 13.0 | 78.3 ± 17.4 | 81.3 ± 16.3 | 82.1 ± 13.1 | 74.9 ± 9.1 | 70.0 ± 11.3 | 71.3 ± 5.8 | 71.4 ± 18.3 |

| 81.5 ± 15.1 (40.0~100.0) | 73.7 ± 12.4 (40.0~100.0) | ||||||||||||||

| Distance from the waterfront(m) | 1.0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 5.5 ± 0.5 | 6.0 | - | 1.8 ± 2.9 | 2.9 ± 4.0 | 5.0 ± 4.5 | 2.7 ± 3.0 | 1.6 ± 1.5 | 5.6 ± 4.9 | 5.9 ± 4.7 | 5.6 ± 4.8 | 6.1 ± 4.6 |

| 4.0 ± 2.2 (1.0~6.0) | 3.4 ± 4.0 (0~12.7) | 5.1 ± 4.8 (0~11.6) | |||||||||||||

| Avg daily temperature (°C) | 8.3 | 7.4 | −3.6 | −1.0 | 5.9 | - | 3.1 | 2.8 | 2.3 | 9.4 | 6.3 | 8.5 | −0.9 | 3.4 | 5.8 |

| 2.7 ± 4.7 (−3.6~8.3) | 4.3 ± 2.9 (2.0~9.4) | 4.9 ± 3.3 (−0.9~8.5) | |||||||||||||

| Variable | BW (g) | Soil Depth (cm) | Soil Temp (°C) | Soil pH | Soil Moisture (%) | Distance from the Waterfront (cm) | Avg Daily Temp (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SVL (mm) | 1.0 ** | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| BW (g) | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| Soil depth (cm) | −0.3 ** | 0.1 | −0.1 | 0.1 | −0.2 * | ||

| Soil temperature (°C) | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.8 ** | |||

| Soil pH | −0.5 ** | 0.3 ** | −0.1 | ||||

| Soil moisture (%) | −0.3 ** | 0.1 | |||||

| Distance from the waterfront (cm) | 0.0 |

| Variable | Field | Laboratory |

|---|---|---|

| Hibernation start and release dates (Duration) | 29 November 2022–29 March 2023 (121 days) | 3 February 2022–25 March 2022 (50 days) |

| Last individual hibernation start temperature (°C) | 3.2~14.7 (Mean 10.2 ± 3.6) | 14.3 |

| First individual hibernation release temperature (°C) | 0.1~17.1 (Mean 8.7 ± 6.4) | 14.4 |

| Number of Dead Individuals (Mortality Rate) | 5 dead out of 31 individuals (16.1%) | 2 dead out of 35 individuals (5.7%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kwon, K.; Park, C.; Yoo, J.; Yoo, N.; Kim, K.-S.; Yoon, J. Assessing the Hibernation Ecology of the Endangered Amphibian, Pelophylax chosenicus Using PIT Tagging Method. Animals 2025, 15, 3638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243638

Kwon K, Park C, Yoo J, Yoo N, Kim K-S, Yoon J. Assessing the Hibernation Ecology of the Endangered Amphibian, Pelophylax chosenicus Using PIT Tagging Method. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243638

Chicago/Turabian StyleKwon, Kwanik, Changdeuk Park, Jeongwoo Yoo, Nakyung Yoo, Keun-Sik Kim, and Juduk Yoon. 2025. "Assessing the Hibernation Ecology of the Endangered Amphibian, Pelophylax chosenicus Using PIT Tagging Method" Animals 15, no. 24: 3638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243638

APA StyleKwon, K., Park, C., Yoo, J., Yoo, N., Kim, K.-S., & Yoon, J. (2025). Assessing the Hibernation Ecology of the Endangered Amphibian, Pelophylax chosenicus Using PIT Tagging Method. Animals, 15(24), 3638. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243638