Mechanism of High-Fat Diet Regulating Rabbit Meat Quality Through Gut Microbiota/Gene Axis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Experimental Library Construction and Sequence

2.4. Quality Control

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Summary of 16S Sequencing Data

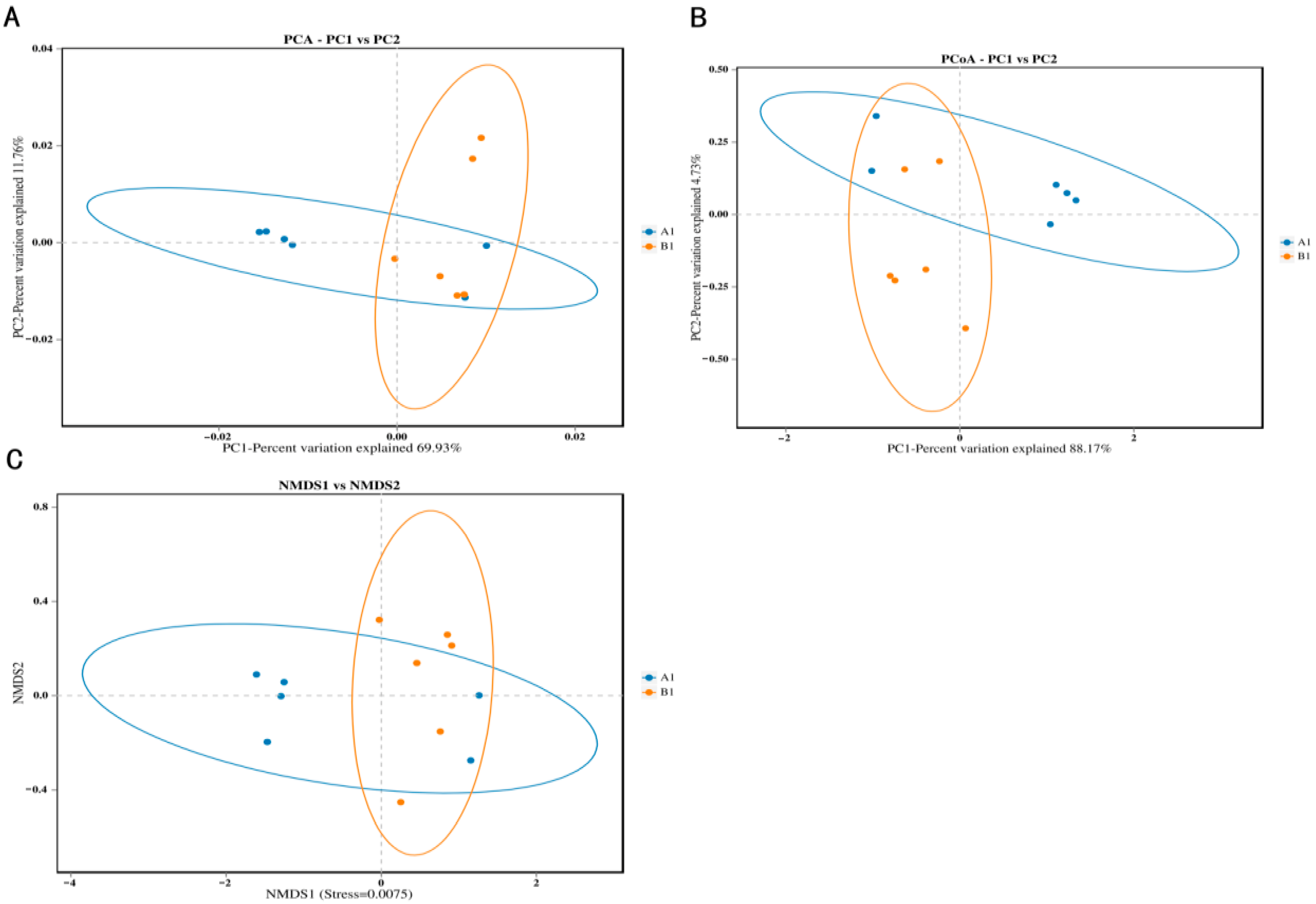

3.2. Diversity of Bacteria

3.3. Bacteria Related to Lipid Metabolism at the Genus Level

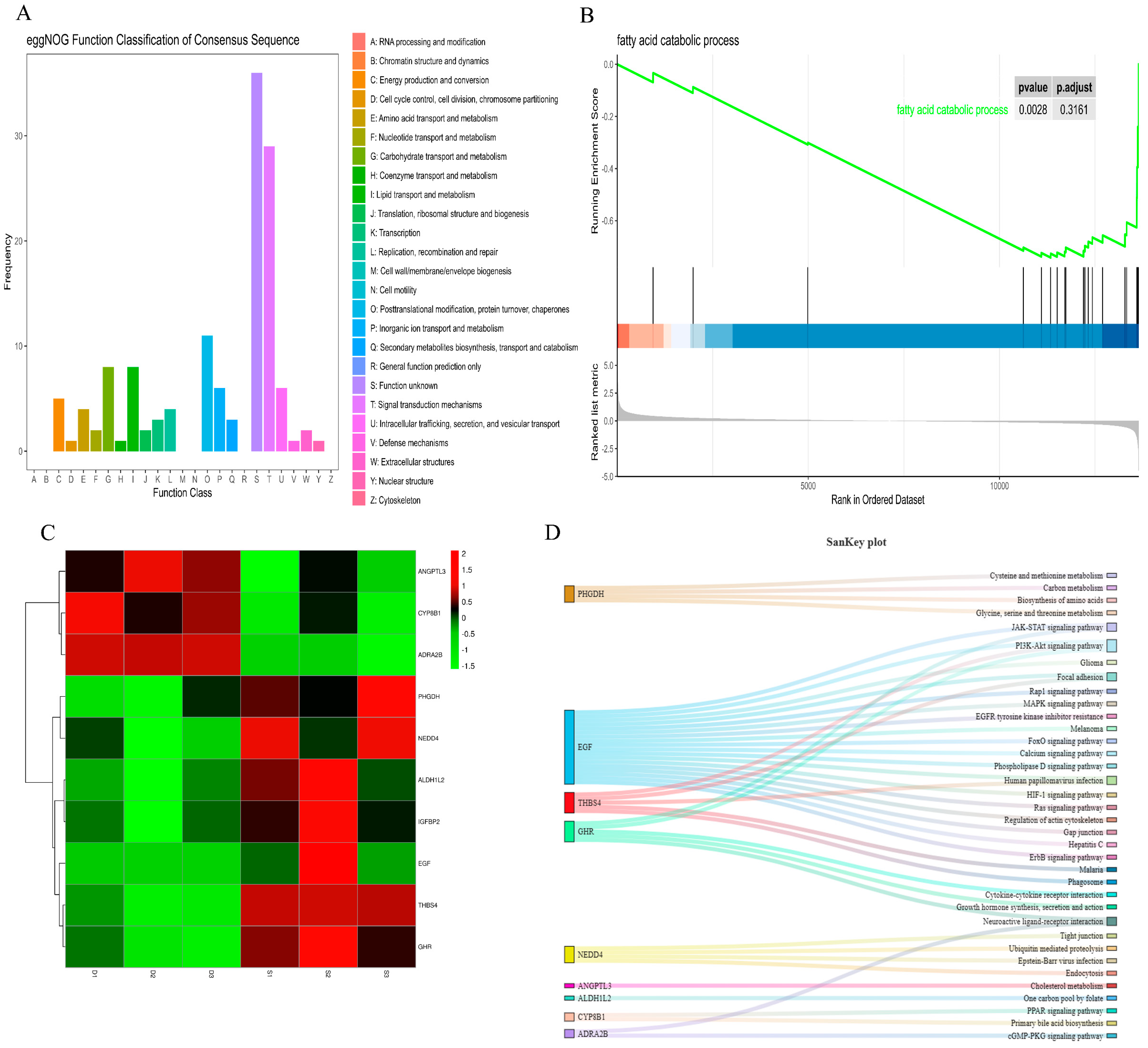

3.4. Functional Distribution of Differentially Expressed Genes

3.5. The Regulatory Mechanism of Differentially Expressed Genes Related to Fat Metabolism

3.6. Regulation Mechanism of Microorganisms on the Meat Quality of Rabbits by Affecting Host Genes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Wang, Z.; He, Z.; Zhang, D.; Li, H.; Wang, Z. Using oxidation kinetic models to predict the quality indices of rabbit meat under different storage temperatures. Meat Sci. 2020, 162, 108042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotte, A.D.; Szendroe, Z. The role of rabbit meat as functional food. Meat Sci. 2011, 88, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Sharma, N.; Narnoliya, L.K.; Verma, A.K.; Umaraw, P.; Mehta, N.; Ismail-Fitry, M.R.; Kaka, U.; Yong-Meng, G.; Lee, S.J. Improving quality and consumer acceptance of rabbit meat: Prospects and challenges. Meat Sci. 2025, 219, 109660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agus, A.; Planchais, J.; Sokol, H. Gut microbiota regulation of tryptophan metabolism in health and disease. Cell Host Microbe Rev. 2018, 23, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eric, P.; Yusuke, I.; Fernando, C.; Shinichiro, N.; Ku, C.J.; Philip, G.; Julia, K.; Hiroyoshi, T.; Mallar, C.M.; Gary, R. Kynurenic acid in schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Bull. 2017, 43, 764–777. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, E.H.; Loftis, J.M.; Blackwell, A.D. Serotonin a la carte: Supplementation with the serotonin precursor 5-hydroxytryptophan. Pharmacol. Ther. 2006, 109, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donaldson, G.P.; Lee, S.M.; Mazmanian, S.K. Gut biogeography of the bacterial microbiota. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 14, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramakrishna, B.S. Role of the gut microbiota in human nutrition and metabolism. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 28, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zmora, N.; Suez, J.; Elinav, E. You are what you eat: Diet, health and the gut microbiota. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 16, 35–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Tang, X.; Sui, Y.; Ren, Z.; Sun, X.; Wang, S. Adding dandelion to rabbit diets: Enhancing the growth performance and meat quality by altering immune competence and gut microbiota. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e00646-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisanz, J.E.; Upadhyay, V.; Turnbaugh, J.A.; Ly, K.; Turnbaugh, P.J. Meta-analysis reveals reproducible gut microbiome alterations in response to a high-fat diet. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 26, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrett, W.S.; Gordon, J.I.; Glimcher, L.H. Homeostasis and inflammation in the intestine. Cell 2010, 140, 859–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; Mcmurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. Dada2: High-resolution sample inference from illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using qiime 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C. Uparse: Highly accurate otu sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 996–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q. Naive bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rrna sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 5261–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloss, P.D.; Westcott, S.L.; Ryabin, T.; Hall, J.R.; Hartmann, M.; Hollister, E.B.; Lesniewski, R.A.; Oakley, B.B.; Parks, D.H.; Robinson, C.J. Introducing mothur: Open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7537–7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, R.; Dai, Q.; Wu, T.; Yang, Z.; Chen, H.; Liu, G.; Zhu, Y.; Qi, D.; Yang, X.; Luo, W.; et al. Fly-over phylogeny across invertebrate to vertebrate: The giant panda and insects share a highly similar gut microbiota. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 4676–4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, P.; Capparelli, R.; Alifano, M.; Iannelli, A.; Iannelli, D. Gut microbiota host-gene interaction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Qi, X.; Wang, Q.; He, Y.; Li, Z.; Cen, X.; Wei, L. Comprehensive analysis of key host gene-microbe networks in the cecum tissues of the obese rabbits induced by a high-fat diet. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1407051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; He, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zeng, C.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, H.; Lv, C.; Yuan, Y.; Wu, H.; Ye, J.; et al. Instant dark tea alleviates hyperlipidaemia in high-fat diet-fed rat: From molecular evidence to redox balance and beyond. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 819980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Kuerbanjiang, M.; Muheyati, D.; Yang, Z.; Han, J. Wheat bran oil ameliorates high-fat diet-induced obesity in rats with alterations in gut microbiota and liver metabolite profile. Nutr. Metab. 2024, 21, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanyu, Z.; Tao, H. Modulatory effects of lactarius hatsudake on obesity and gut microbiota in high-fat diet-fed c57bl/6 mice. Foods 2024, 13, 948. [Google Scholar]

- Zubiria, I.; Garcia-Rodriguez, A.; Atxaerandio, R.; Ruiz, R.; Benhissi, H.; Mandaluniz, N.; Lavín, J.L.; Abecia, L.; Goiri, I. Effect of feeding cold-pressed sunflower cake on ruminal fermentation, lipid metabolism and bacterial community in dairy cows. Animals 2019, 9, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Bai, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, X.; Fortina, R.; Gasco, L.; Guo, K. Impact of high-moisture ear corn on antioxidant capacity, immunity, rumen fermentation, and microbial diversity in pluriparous dairy cows. Fermentation 2024, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Zhao, S.; Jeon, B.H.; Salama, E.S.; Li, X. Microbial β-oxidation of synthetic long-chain fatty acids to improve lipid biomethanation. Water Res. 2022, 213, 118164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Guo, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; Ou, Z.; Peng, Y. Phascolarctobacterium faecium abundant colonization in human gastrointestinal tract. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 14, 3122–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ana, D.-V.; Antonio, V.; Cristina, S.-P. Halonotius aquaticus sp. Nov., a new haloarchaeon isolated from a marine saltern. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 1306–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagar, D.N.; Mani, K.; Braganca, J.M. Genomic insights on carotenoid synthesis by extremely halophilic archaea Haloarcula rubripromontorii bs2, Haloferax lucentense bbk2 and Halogeometricum borinquense e3 isolated from the solar salterns of India. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Feng, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chang, X.; Yang, G.; Meng, X. Effects of pasteurized akkermansia muciniphila on lipid metabolism disorders induced by high-fat diet in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Microelectron. J. 2024, 38, 102363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.S.; Jiang, H.; Xiao, J.; Yan, X.; Xie, P.; Yu, W.; Lv, W.F.; Wang, J.; Meng, X.; Chen, C.Z. Changes in bacterial community composition in the uterus of holstein cow with endometritis before and after treatment with oxytetracycline. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, I.; Marodin, G.; Lupo, M.G.; Ferri, N. Angptl3 silencing induces hepatic fat accumulation by inducing de novo lipogenesis in a pcsk9-independent manner. Atherosclerosis 2024, 395, 118400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertaggia, E.; Jensen, K.K.; Castro-Perez, J.; Xu, Y.; Di Paolo, G.; Chan, R.B.; Wang, L.; Haeusler, R.A. Cyp8b1 ablation prevents western diet-induced weight gain and hepatic steatosis due to impaired fat absorption. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 313, E121–E133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Cui, Y.; Fan, X.; Qi, P.; Zhang, X. Anti-obesity effects of spirulina platensis protein hydrolysate by modulating brain-liver axis in high-fat diet fed mice. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, D.; Feng, Y.; Yin, J.; Zhou, X. Exogenous and endogenous serine deficiency exacerbates hepatic lipid accumulation. Hindawi Ltd 2021, 2021, 4232704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, L.J. Role of lipid domains in EGF receptor signaling. In Handbook of Cell Signaling, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010; pp. 323–326. [Google Scholar]

- Senevirathna, J.; Yonezawa, R.; Igarashi, Y.; Saka, T.; Asakawa, S. Potential candidate genes and pathways affecting the metabolism of jaw fats in risso’s dolphin: Based on transcriptomics. Res. Sq. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Antonio, J.; Fernandez-Alarcon, M.F.; Lunedo, R.; Squassoni, G.H.; Ferraz, A.L.J.; Macari, M.; Furlan, R.L.; Furlan, L.R. Chronic heat stress and feed restriction affects carcass composition and the expression of genes involved in the control of fat deposition in broilers. J. Agric. Sci. 2017, 155, 1487–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, L.J.; Ferry, R.J.; Shiyong, D.; Bingzhong, X.; Bahouth, S.W.; Francesca-Fang, L. Nedd4 haploinsufficient mice display moderate insulin resistance, enhanced lipolysis, and protection against high-fat diet-induced obesity. Endocrinology 2015, 156, 1283–1291. [Google Scholar]

- You, M.; Sharma, J.; Fogle, H.M.; Mccormac, J.P.; Krupenko, N.; Krupenko, S. P10-029-23 aldh1l2 controls high-fat diet induced obesity-linked pathways in female mice. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2023, 7, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, H.; Jiang, W.; Gao, J.; Ma, Z.; Li, C.; Peng, Y.; Jin, J.; Zhan, X.; Lv, W.; Liu, X. Syisl knockout promotes embryonic muscle development of offspring by modulating maternal gut microbiota and fetal myogenic cell dynamics. Adv. Sci. 2024, 12, 2410953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Yang, L.; Ding, J.; Dai, R.; He, C.; Xu, K.; Luo, L.; Xiao, L.; Zheng, Y.; Han, C. Intestinal microbiota and host cooperate for adaptation as a hologenome. mSystems 2022, 7, e0126121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Wu, Y.L.; Ding, H.; Xie, K.Z.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, G.X.; Wang, J.Y. Phgdh promotes the proliferation and differentiation of primary chicken myoblasts. Br. Poult. Sci. 2022, 63, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J. Effect of Nedd4 Haploinsufficiency on Insulin Sensitivity, Adiposity and Neuronal Behaviors. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kumari, A.; Larsen, S.W.R.; Bondesen, S.; Qian, Y.; Tian, H.D.; Walker, S.G.; Davies, B.S.J.; Remaley, A.T.; Young, S.G.; Konrad, R.J. Angptl3/8 is an atypical unfoldase that regulates intravascular lipolysis by catalyzing unfolding of lipoprotein lipase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2420721122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Huang, C.; He, C.; Yang, T.; Ren, R.; Xin, Z.; Wang, X. Quercetin-driven Akkermansia muciniphila alleviates obesity by modulating bile acid metabolism via an ila/m(6)a/cyp8b1 signaling. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e2412865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Kingdom | Phylum | Order | Family | Genus | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L35D1 | 2 | 42 | 247 | 455 | 860 | 1490 |

| L35D2 | 2 | 34 | 193 | 338 | 608 | 981 |

| L35D3 | 2 | 43 | 259 | 473 | 884 | 1467 |

| L35D4 | 2 | 42 | 246 | 456 | 844 | 1414 |

| L35D5 | 2 | 26 | 131 | 210 | 317 | 393 |

| L35D6 | 2 | 41 | 250 | 438 | 845 | 1449 |

| L35S1 | 2 | 41 | 220 | 383 | 691 | 1041 |

| L35S2 | 2 | 36 | 180 | 293 | 485 | 635 |

| L35S3 | 2 | 28 | 162 | 264 | 418 | 575 |

| L35S4 | 2 | 33 | 181 | 307 | 506 | 730 |

| L35S5 | 2 | 36 | 176 | 286 | 480 | 632 |

| L35S6 | 2 | 37 | 194 | 316 | 551 | 766 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luo, G.; Xue, T.; Du, K.; Ren, Z.; Luo, Y. Mechanism of High-Fat Diet Regulating Rabbit Meat Quality Through Gut Microbiota/Gene Axis. Animals 2025, 15, 3608. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243608

Luo G, Xue T, Du K, Ren Z, Luo Y. Mechanism of High-Fat Diet Regulating Rabbit Meat Quality Through Gut Microbiota/Gene Axis. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3608. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243608

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuo, Gang, Tongtong Xue, Kun Du, Zhanjun Ren, and Yongzhen Luo. 2025. "Mechanism of High-Fat Diet Regulating Rabbit Meat Quality Through Gut Microbiota/Gene Axis" Animals 15, no. 24: 3608. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243608

APA StyleLuo, G., Xue, T., Du, K., Ren, Z., & Luo, Y. (2025). Mechanism of High-Fat Diet Regulating Rabbit Meat Quality Through Gut Microbiota/Gene Axis. Animals, 15(24), 3608. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243608