High-Efficiency Cryopreservation of Silver Pomfret Sperm: Protocol Development and Cryodamage Assessment

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fish Source

2.2. Sperm Collection

2.3. Extender Preparation

2.4. Evaluation of Extender Types

2.5. Evaluation of Permeable Cryoprotectants

2.6. Evaluation for Dilution Ratio, Cooling Height, and Thawing Temperature

2.7. Sperm Kinetic Analysis Using CASA

2.8. Effect of Cryopreservation on Sperm Enzyme Activity

2.9. Ultrastructural Analysis of Cryopreserved Sperm

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of Extenders for Silver Pomfret Sperm Cryopreservation

3.2. Effects of Different Cryoprotectants on the Preservation Outcomes of Silver Pomfret Sperm

3.3. Effects of Different Sperm Dilution Ratios on Cryopreservation Outcomes

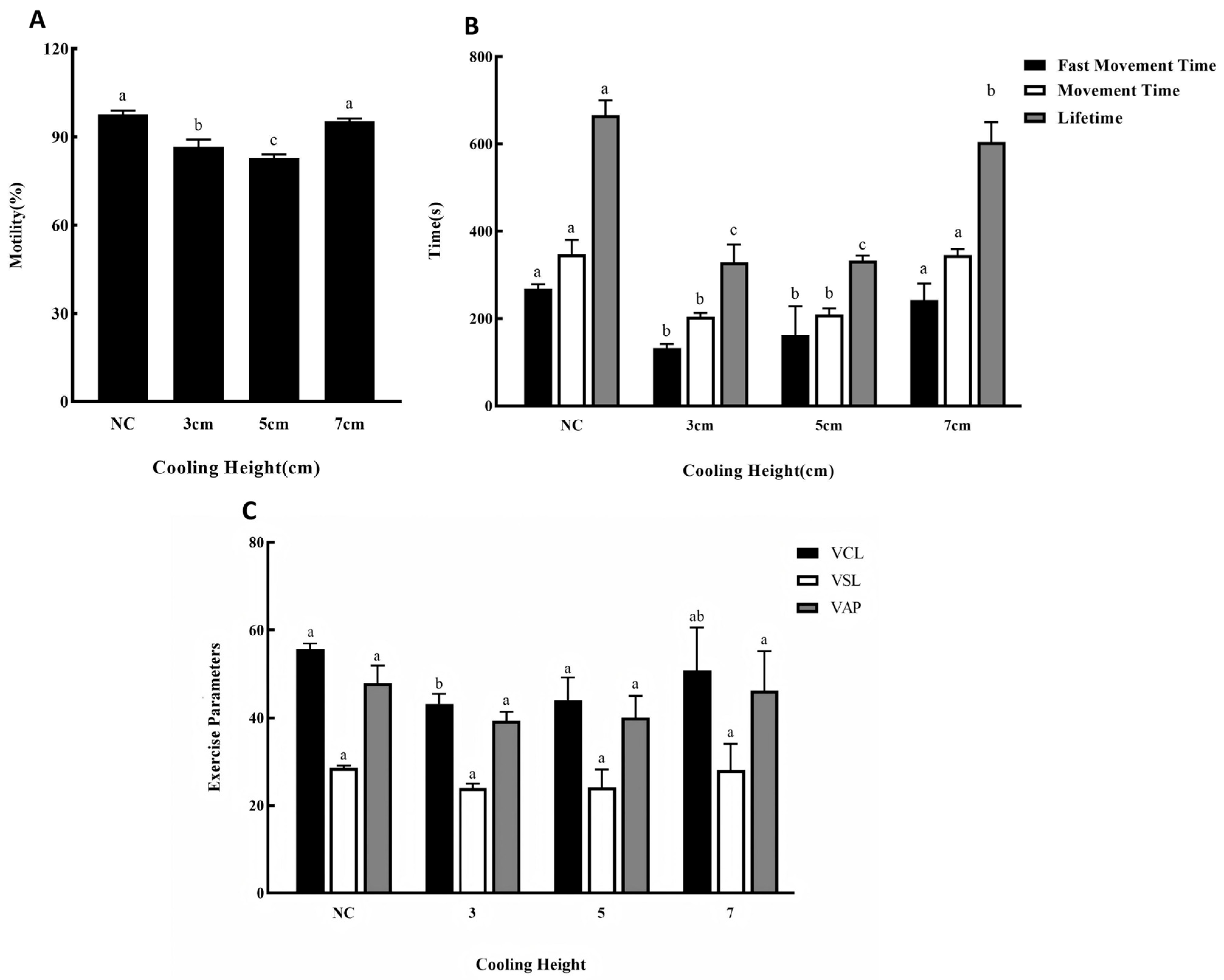

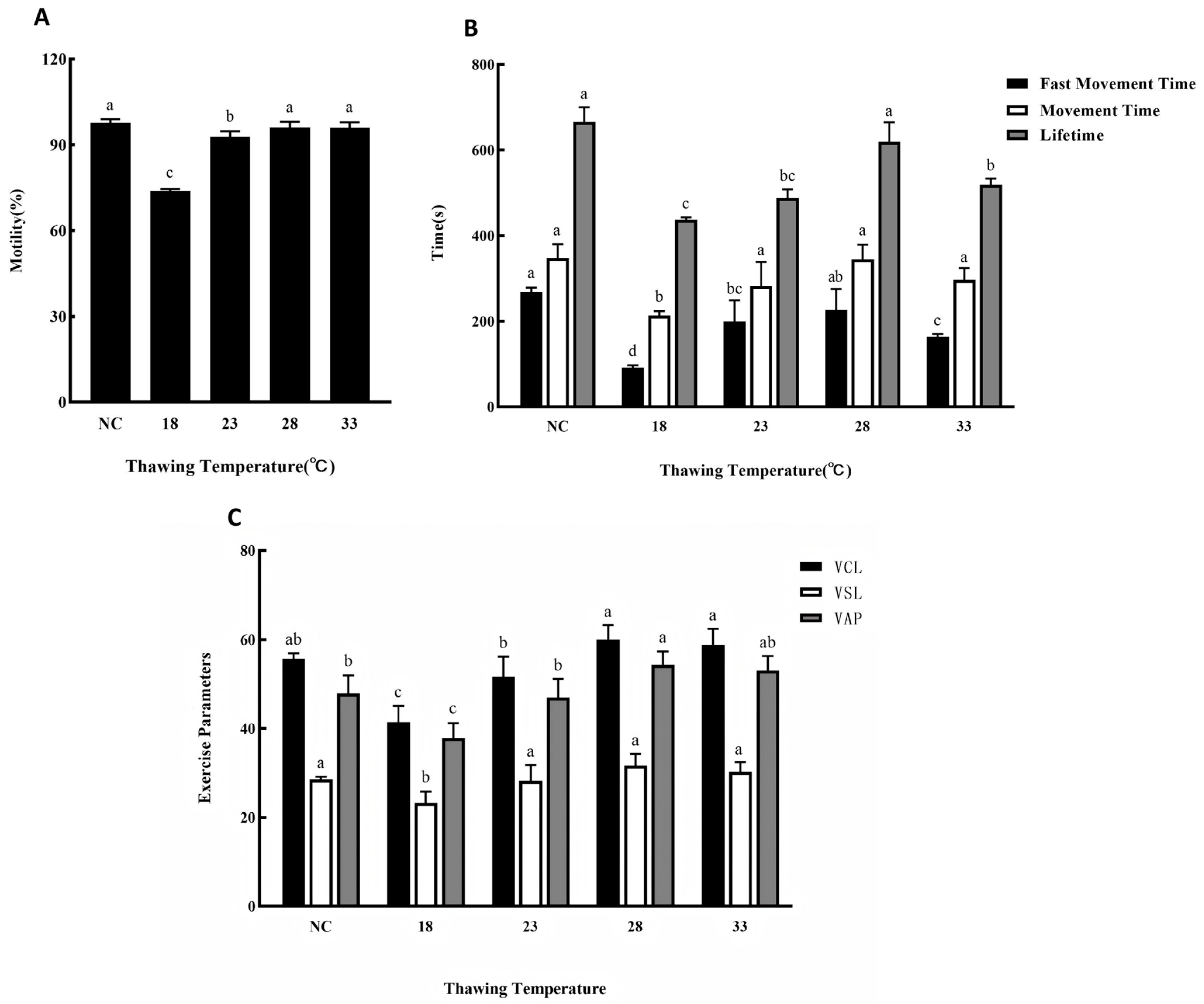

3.4. Effects of Different Cooling Height on Cryopreservation Outcomes

3.5. Effects of Different Thawing Temperatures on Cryopreservation Outcomes

3.6. Effect of Ultra-Low-Temperature Cryopreservation on Enzyme Activity of Silver Pomfret Sperm

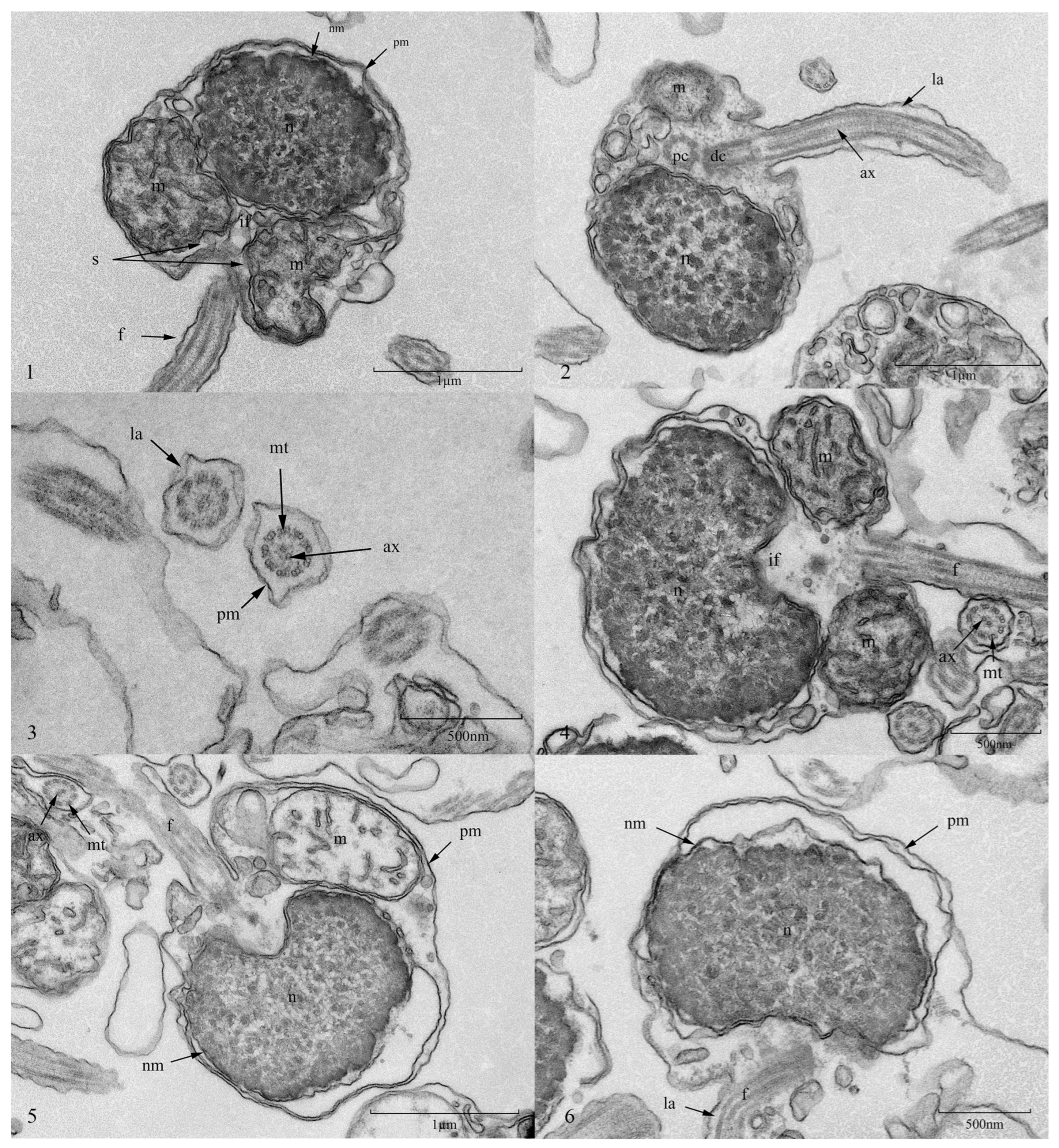

3.7. Effect of Ultra-Low-Temperature Cryopreservation on the Ultrastructure of Silver Pomfret Sperm

4. Discussion

4.1. Determination of the Optimal Conditions for Cryopreservation of Silver Pomfret Sperm

4.1.1. Appropriate Diluent: MPRS

4.1.2. Appropriate Cryoprotectant: EG

4.1.3. The Optimal Dilution Ratio: 1:6

4.1.4. Optimal Cooling Height: 7 cm

4.1.5. Optimal Thawing Temperature: 28 °C

4.2. Effect of Cryopreservation on Enzyme Activities in Silver Pomfret Sperm

4.3. Effect of Cryopreservation on the Ultrastructure of Silver Pomfret Sperm

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, P.; Yin, F.; Shi, Z.; Peng, S. Genetic structure of silver pomfret (Pampus argenteus (Euphrasen, 1788)) in the Arabian Sea, Bay of Bengal, and South China Sea as indicated by mitochondrial COI gene sequences. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2013, 29, 733–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqattan, M.E.A.; Gray, T. Marine Pollution in Kuwait and Its Impacts on Fish-Stock Decline in Kuwaiti Waters: Reviewing the Kuwaiti Government’s Policies and Practices. Front. Sustain. 2021, 2, 667822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, F.; Islam, M.M.; Iida, M.; Zahangir, M.M. Reproductive seasonality and the gonadal maturation of silver pomfret Pampus argenteus in the Bay of Bengal, Bangladesh. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. UK 2020, 100, 1155–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadzie, S.; Abou-Seedo, F.; Al-Shallal, T. Reproductive biology of the silver pomfret, Pampus argenteus (Euphrasen), in Kuwait waters. J. Appl. Ichthyol.-Z. Angew. Ichthyol. 2000, 16, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Du, C.; Gao, X.; Ni, J.; Wang, Y.; Hou, C.; Zhu, J.; Tang, D. Changes in the histology and digestive enzyme activity during digestive system development of silver pomfret (Pampus argenteus). Aquaculture 2023, 577, 739905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abdul-Elah, K.; Hossain, M.A.; Akatsu, S. Recent advances in artificial breeding and larval rearing of silver pomfret Pampus argenteus (Euphrasen 1788) in Kuwait. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 5808–5815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Q.; Fang, Z.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Y.; Wan, Z.; Xu, S.; Guo, C. Study on tolerance, tissue damage and oxidative stress of juvenile silver pomfret (Pampus argenteus) under copper sulfate, formaldehyde and freshwater stress. Aquaculture 2025, 599, 742134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopeika, E.; Kopeika, J.; Zhang, T. Cryopreservation of fish sperm. Methods Mol. Biol. 2007, 368, 203–217. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Yao, J.; Zeng, L.; Feng, K.; Zhou, C.; Liu, H.; Wang, W.; Zhou, J.; Xu, H. Developing Efficient Methods of Sperm Cryopreservation for Three Fish Species (Cyprinus carpio L., Schizothorax prenanti, Glyptosternum maculatum). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.Y.; Park, J.Y.; Lim, H.K. Effects of different diluents, cryoprotective agents, and freezing rates on sperm cryopreservation in Epinephelus akaara. Cryobiology 2018, 83, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Guan, J.; Hua, Y. Optimization of sperm cryopreservation protocol for Basa catfish (Pangasius bocourti). Cryobiology 2023, 111, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Fan, B.; Chen, X.; Meng, Z. Cryopreservation of sperm in brown-marbled grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus). Aquac. Int. 2020, 28, 1501–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, I.C.C.; Yokoi, K.-I.; Tsuji, M.; Tsuchihashi, Y.; Ohta, H. Cryopreservation of sperm from seven-band grouper, Epinephelus septemfasciatus. Cryobiology 2010, 61, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazur, P. Freezing of living cells: Mechanisms and implications. Am. J. Physiol. 1984, 247, C125–C142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, J.-M.; Zhu, K.-C.; Liu, J.; Guo, H.-Y.; Liu, B.-S.; Zhang, N.; Xian, L.; Sun, J.-H.; Zhang, D.-C. Cryopreservation of black seabream (Acanthopagrus schlegelii) sperm. Theriogenology 2023, 210, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labbe, C.; Martoriati, A.; Devaux, A.; Maisse, G. Effect of sperm cryopreservation on sperm DNA stability and progeny development in rainbow trout. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2001, 60, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zilli, L.; Schiavone, R.; Zonno, V.; Storelli, C.; Vilella, S. Evaluation of DNA damage in Dicentrarchus labrax sperm following cryopreservation. Cryobiology 2003, 47, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muchlisin, Z.A.; Azizah, M.N.S. Influence of cryoprotectants on abnormality and motility of baung (Mystus nemurus) spermatozoa after long-term cryopreservation. Cryobiology 2009, 58, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rurangwa, E.; Volckaert, F.A.M.; Huyskens, G.; Kime, D.E.; Ollevier, F. Quality control of refrigerated and cryopreserved semen using computer-assisted sperm analysis (CASA), viable staining and standardized fertilization in African catfish (Clarias gariepinus). Theriogenology 2001, 55, 751–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh Hoang, L.; Lim, H.K.; Min, B.H.; Park, M.S.; Chang, Y.J. Storage of Yellow Croaker Larimichthys polyactis Semen. Isr. J. Aquac.-Bamidgeh 2011, 63, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.Z.; Zhang, S.C.; Liu, X.Z.; Xu, Y.Y.; Wang, C.L.; Sawant, M.S.; Li, J.; Chen, S.L. Cryopreservation of flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) sperm with a practical methodology. Theriogenology 2003, 60, 989–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.Y.; Woods, L.C. Changes in motility, ultrastructure, and fertilization capacity of striped bass Morone saxatilis spermatozoa following cryopreservation. Aquaculture 2004, 236, 677–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, V.; Asturiano, J.F. Sperm motility in fish: Technical applications and perspectives through CASA-Mot systems. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2018, 30, 820–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogretmen, F.; Inanan, B.E.; Kutluyer, F. Combined effects of physicochemical variables (pH and salinity) on sperm motility: Characterization of sperm motility in European sea bass Dicentrarchus labrax. Mar. Freshw. Behav. Physiol. 2016, 49, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irawan, H.; Vuthiphandchai, V.; Nimrat, S. The effect of extenders, cryoprotectants and cryopreservation methods on common carp (Cyprinus carpio) sperm. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2010, 122, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judycka, S.; Nynca, J.; Ciereszko, A. Opportunities and challenges related to the implementation of sperm cryopreservation into breeding of salmonid fishes. Theriogenology 2019, 132, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yingzhe, Y. Research on cryopreservation of Takifugu bimaculatus spermatozoa. Fish. Mod. 2017, 44, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, P.Y.; Guo, H.Y.; Liu, B.D.; Guo, L.; Zhang, N.; Zhu, K.C.; Jiang, S.G.; Zhang, D.C. Effects of cryopreservation on the physiological characteristics and enzyme activities of yellowfin seabream sperm, Acanthopagrus latus (Houttuyn 1782). Aquaculture 2022, 549, 737739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Liu, X.C.; Meng, Z.N.; Tan, B.H.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.X.; Lin, H.R. Cryopreservation of giant grouper Epinephelus lanceolatus (Bloch, 1790) sperm. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2014, 30, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.S.; Chen, S.L.; Tian, Y.S.; Yu, G.C.; Sha, Z.X.; Xu, M.Y.; Zhang, S.C. Cryopreservation of sea perch (Lateolabrax japonicus) spermatozoa and feasibility for production-scale fertilization. Aquaculture 2004, 241, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrita, E.; Robles, V.; Rebordinos, L.; Sarasquete, C.; Herráez, M.P. Evaluation of DNA damage in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) cryopreserved sperm. Cryobiology 2005, 50, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, E.; Valdebenito, I.; Zepeda, A.B.; Figueroa, C.A.; Dumorné, K.; Castillo, R.L.; Farias, J.G. Effects of cryopreservation on mitochondria of fish spermatozoa. Rev. Aquac. 2017, 9, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreanno, C.; Suquet, M.; Quemener, L.; Cosson, J.; Fierville, F.; Normant, Y.; Billard, R. Cryopreservation of turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) spermatozoa. Theriogenology 1997, 48, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tekin, N.; Secer, S.; Akcay, E.; Bozkurt, Y.; Kayam, S. Effects of glycerol additions on post-thaw fertility of frozen rainbow trout sperm, with an emphasis on interaction between extender and cryoprotectant. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2007, 23, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, I.; Mohammad, L.J.; Suvitha, A.; Haidari, Z.; Schiöth, H.B. Comprehensive overview of the toxicities of small-molecule cryoprotectants for carnivorous spermatozoa: Foundation for computational cryobiotechnology. Front Toxicol 2025, 7, 1477822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuthiphandchai, V.; Chomphuthawach, S.; Nimrat, S. Cryopreservation of red snapper (Lutjanus argentimaculatus) sperm: Effect of cryoprotectants and cooling rates on sperm motility, sperm viability, and fertilization capacity. Theriogenology 2009, 72, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viveiros, A.T.M.; Nascimento, A.F.; Leal, M.C.; Gonçalves, A.C.S.; Orfão, L.H.; Cosson, J. Methyl glycol, methanol and DMSO effects on post-thaw motility, velocities, membrane integrity and mitochondrial function of Brycon orbignyanus and Prochilodus lineatus (Characiformes) sperm. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 41, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zidni, I.; Kim, K.W.; Jang, H.S.; Heo, M.S.; Kim, K.S.; Yoon, J.D.; Lim, H.K. Cryopreservation of sperm from the gudgeon, Microphysogobio rapidus (Cyprinidae): Effects of cryoprotectant, diluents, and dilution ratio. Cryobiology 2024, 115, 104869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrita, E.; Robles, V.; Cuñado, S.; Wallace, J.C.; Sarasquete, C.; Herráez, M.P. Evaluation of gilthead sea bream, Sparus aurata, sperm quality after cryopreservation in 5 mL macrotubes. Cryobiology 2005, 50, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrita, E.; Sarasquete, C.; Martínez-Páramo, S.; Robles, V.; Beiro, J.; Pérez-Cerezales, S.; Herráez, M.P. Cryopreservation of fish sperm: Applications and perspectives. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2010, 26, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.L.; Ji, X.S.; Yu, G.C.; Tian, Y.S.; Sha, Z.X. Cryopreservation of sperm from turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) and application to large-scale fertilization. Aquaculture 2004, 236, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Zheng, X.; Jiang, J.; Meng, J.; Zhu, J. The effects of extenders, cryoprotectants and conditions in two-step cooling method on Varicorhinus barbatulus sperm. Cryobiology 2021, 100, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, P. The role of intracellular freezing in the death of cells cooled at supraoptimal rates. Cryobiology 1977, 14, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, G.J.; Acton, E.; Murray, B.J.; Fonseca, F. Freezing injury: The special case of the sperm cell. Cryobiology 2012, 64, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suquet, M.; Dreanno, C.; Fauvel, C.; Cosson, J.; Billard, R. Cryopreservation of sperm in marine fish. Aquac. Res. 2000, 31, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carolsfeld, J.; Godinho, H.P.; Filho, E.Z.; Harvey, B.J. Cryopreservation of sperm in Brazilian migratory fish conservation. J. Fish Biol. 2003, 63, 472–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kommisrud, E.; Myromslien, F.; Stenseth, E.B.; Sunde, J. Viability, motility, ATP content and fertilizing potential of sperm from Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) in milt stored before cryopreservation. Theriogenology 2020, 151, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Huang, W.; Chen, H.; Huang, M.; Meng, Z. Effect of chilled storage on sperm quality of basa catfish (Pangasius bocourti). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 46, 2133–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueroa, E.; Lee-Estevez, M.; Valdebenito, I.; Watanabe, I.; Farías, J.G. Effects of cryopreservation on mitochondrial function and sperm quality in fish. Aquaculture 2019, 511, 634190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, A. Energy metabolism in mammalian sperm motility. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 2022, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Wang, G.; Chen, Z.; Chen, X.; Bi, S.; Lai, H.; Zhao, X.; Guo, D.; Li, G. Changes in sperm parameters of sex-reversed female mandarin fish Siniperca chuatsi during cryopreservation process. Theriogenology 2019, 133, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, P.; Liu, H.; Li, R.; Li, Z.; He, Y.; Qi, J. Effects of Cryopreservation on Sperm with Cryodiluent in Viviparous Black Rockfish (Sebastes schlegelii). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butts, I.A.E.; Rideout, R.M.; Burt, K.; Samuelson, S.; Lush, L.; Litvak, M.K.; Trippel, E.A.; Hamoutene, D. Quantitative semen parameters of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) and their physiological relationships with sperm activity and morphology. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2010, 26, 756–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.R.; Zhuang, P.; Zhang, L.Z.; Liu, J.Y.; Zhang, T.; Feng, G.P.; Zhao, F. Effect of cryopreservation on the enzyme activity of Russian sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedtii Brandt & Ratzeburg, 1833) semen. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2014, 30, 1585–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billard, R. Ultrastructure of trout spermatozoa: Changes after dilution and deep-freezing. Cell Tissue Res. 1983, 228, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBaulny, B.O.; LeVern, Y.; Kerboeuf, D.; Maisse, G. Flow cytometric evaluation of mitochondrial activity and membrane integrity in fresh and cryopreserved rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) spermatozoa. Cryobiology 1997, 34, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarder, M.R.I.; Saha, S.K.; Sarker, M.F.M. Cryopreservation of Sperm of an Indigenous Endangered Fish, Pabda Catfish Ompok pabda. N. Am. J. Aquac. 2013, 75, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component (mM) | HBSS | MPRS | Cortland | Ringer’s | Hank’s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaCl | 136.89 | 60.40 | 124.06 | 111.23 | 136.89 |

| KCl | 5.37 | 5.23 | 5.10 | 1.88 | 5.37 |

| CaCl2 | - | - | 1.62 | - | 1.26 |

| CaC12·2H2O | 1.09 | 1.16 | - | 0.82 | - |

| NaHCO3 | 4.17 | 2.98 | 11.9 | 2.38 | 4.17 |

| KH2PO4 | 0.44 | - | - | - | 0.44 |

| MgSO4·7H2O | 0.81 | - | 0.93 | - | 0.41 |

| MgCl2·6H2O | - | 1.13 | - | - | 0.49 |

| Na2HPO4·7H2O | 0.45 | - | - | - | - |

| NaH2PO4 | - | 1.83 | - | 0.08 | - |

| NaH2PO4·2H2O | - | - | 2.63 | - | - |

| Na2HPO4·12H2O | - | - | - | - | 0.18 |

| Glucose | 5.55 | 55.51 | 5.55 | - | 55.51 |

| pH | 7.2 | 6.68 | 7 | 7.4 | 6.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, M.; Jiang, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Feng, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Dai, Q.; Hu, J.; Yan, X.; et al. High-Efficiency Cryopreservation of Silver Pomfret Sperm: Protocol Development and Cryodamage Assessment. Animals 2025, 15, 3602. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243602

Zhang M, Jiang Y, Qiu Y, Feng Z, Chen X, Wang C, Li Y, Dai Q, Hu J, Yan X, et al. High-Efficiency Cryopreservation of Silver Pomfret Sperm: Protocol Development and Cryodamage Assessment. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3602. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243602

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Man, Yijun Jiang, Yubei Qiu, Zukang Feng, Xianglong Chen, Chongyang Wang, Yuanbo Li, Qinqin Dai, Jiabao Hu, Xiaojun Yan, and et al. 2025. "High-Efficiency Cryopreservation of Silver Pomfret Sperm: Protocol Development and Cryodamage Assessment" Animals 15, no. 24: 3602. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243602

APA StyleZhang, M., Jiang, Y., Qiu, Y., Feng, Z., Chen, X., Wang, C., Li, Y., Dai, Q., Hu, J., Yan, X., & Wang, Y. (2025). High-Efficiency Cryopreservation of Silver Pomfret Sperm: Protocol Development and Cryodamage Assessment. Animals, 15(24), 3602. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243602