Design and Verification of a Non-Contact Body Dimension Measurement System for Jiangquan Black Pigs Based on Dual-View Depth Vision

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

- −

- Projection methods relied on grids and stereoscopic projection principles for calculations. However, the efficacy of these methods is contingent upon the utilization of specialized equipment and the execution of manual interventions, which engenders challenges related to automation [12].

- −

- −

- 3D imaging method: The utilization of depth cameras to capture three-dimensional point cloud data of the pig’s back facilitates the extraction of multidimensional feature parameters, including height. These parameters exhibit strong correlations with weight and body conformation, demonstrating significant application potential. This approach has been demonstrated to yield superior mean absolute error (MAE) performance in body conformation estimation [15,16,17].

- −

- −

- Deep learning-driven image feature fusion methods utilize models like CNNs and Transformers to automatically extract high-dimensional semantic features and fuse multimodal information (e.g., RGB images + texture features, local regions + global morphological features) to construct weight estimation models, eliminating the need for manual feature design [20,21,22].

- −

- Multi-view image fusion weight estimation methods combine multi-angle image data (e.g., top-view + side-view, front-view + side-view) to compensate for single-view information limitations through registration and feature fusion, constructing more comprehensive body shape representation models [23,24,25,26].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reference Manual Measurements

- −

- Body Length (BL): Distance from the midpoint between the ears to the tail root.

- −

- Body Width (BW): Measured at the maximum abdominal width.

- −

- Body Height (BH): Vertical distance from the scapular summit (withers) to the ground.

- −

- Chest Depth(CD): is defined as the vertical distance from the highest point of the withers to the lowest point of the sternum behind the shoulder blades.

- −

- Bust: Using a tape measure with an accuracy of 0.1 cm, encircle the pig’s body at the intersection point between the posterior edge of the scapula and the widest part of the thoracic cage. Keep the tape measure horizontal and snug against the skin, avoiding compression of soft tissue.

2.2. Hardware System and Data Acquisition

2.3. Image Pre-Processing and Segmentation

2.4. Acquisition of Body Dimensions and Automated Weight Estimation

- : The actual physical length of the pig body target dimension (unit: cm), i.e., the final output body length or body width .

- : length of the pig’s target dimensions (body length/body width) (unit: pixel), calculated by the difference in pixel coordinates between the selected endpoints.

- : The average depth value (in meters) of the region corresponding to the pig’s target dimension is obtained by statistical analysis of the depth data from the corresponding area in the depth map.

- : Step 1 The effective focal length of the camera obtained through calibration (unit: pixels).

2.5. Statistical Analysis and Model Validation

3. Results

3.1. Accuracy Assessment of Automated Body Dimension Measurements

3.2. Performance Comparison of Chest Girth Fitting Algorithms

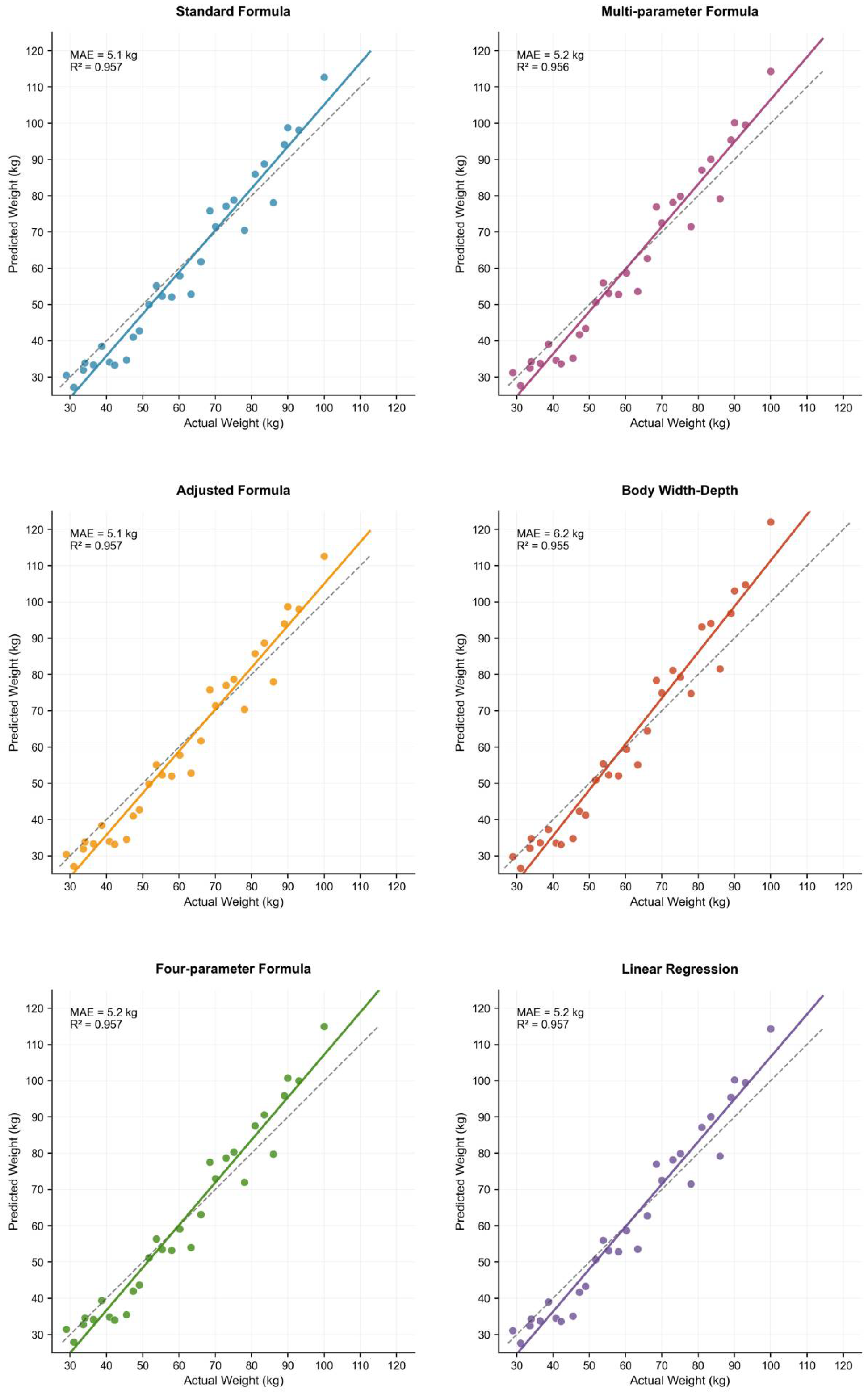

3.3. Development and Validation of Body Weight Estimation Models

4. Discussion

4.1. Core Performance Advantages of the Dual-View Depth Vision Measurement System

4.2. Key Technological Innovations and Principal Validation

4.3. Comparison with Existing Research

4.4. Future Research Directions and Application Prospects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tu, S.; Ou, H.; Mao, L.; Du, J.; Cao, Y.; Chen, W. Behavior Tracking and Analyses of Group-Housed Pigs Based on Improved ByteTrack. Animals 2024, 14, 3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jiang, H.; Qiao, Y.; Jiang, S.; Lin, H.; Sun, Q. The Research Progress of Vision-Based Artificial Intelligence in Smart Pig Farming. Sensors 2022, 22, 6541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Wu, P.; Cui, H.; Xuan, C.; Su, H. Identification and Classification for Sheep Foraging Behavior Based on Acoustic Signal and Deep Learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 187, 106275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongsro, J. Estimation of Pig Weight Using a Microsoft Kinect Prototype Imaging System. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2014, 109, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravcsíková, Á.; Vyskočilová, Z.; Šustr, P.; Bartošová, J. Validating Ultra-Wideband Positioning System for Precision Cow Tracking in a Commercial Free-Stall Barn. Animals 2024, 14, 3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Yuan, Z.; Luo, X.; Liang, J.; Wang, C. Research on Behavior Recognition and Online Monitoring System for Liaoning Cashmere Goats Based on Deep Learning. Animals 2024, 14, 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menesatti, P.; Costa, C.; Antonucci, F.; Steri, R.; Pallottino, F.; Catillo, G. A Low-Cost Stereovision System to Estimate Size and Weight of Live Sheep. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2014, 103, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, A.R.; Schofield, C.P.; Beaulah, S.A.; Mottram, T.T.; Lines, J.A.; Wathes, C.M. A Review of Livestock Monitoring and the Need for Integrated Systems. Comput. Electron. Agric. 1997, 17, 139–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Wang, S.; Lv, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zeng, L. Research on Global Actual Measurement of Indoor Surface Flatness and Verticality Based on Sparse Point Cloud. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2215, 012015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarlane, N.J.B.; Wu, J.; Tillett, R.D.; Schofield, C.P.; Siebert, J.P.; Ju, X. Shape Measurements of Live Pigs Using 3-D Image Capture. Anim. Sci. 2005, 81, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doeschl-Wilson, A.B.; Whittemore, C.T.; Knap, P.W.; Schofield, C.P. Using Visual Image Analysis to Describe Pig Growth in Terms of Size and Shape. Anim. Sci. 2004, 79, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhuang, Y.; Ji, H.; Teng, G. Pig Weight and Body Size Estimation Using a Multiple Output Regression Convolutional Neural Network: A Fast and Fully Automatic Method. Sensors 2021, 21, 3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, C.P.; Marchant, J.A.; White, R.P.; Brandl, N.; Wilson, M. Monitoring Pig Growth Using a Prototype Imaging System. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1999, 72, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Bian, Y.; Wang, T.; Xue, H.; Liu, L. Estimation of Weight and Body Measurement Model for Pigs Based on Back Point Cloud Data. Animals 2024, 14, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Teng, G.; Li, Z. An Approach of Pig Weight Estimation Using Binocular Stereo System Based on LabVIEW. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2016, 129, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, Q.; He, D. An Improved PointNet++ Point Cloud Segmentation Model Applied to Automatic Measurement Method of Pig Body Size. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 205, 107560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Qiao, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, J. Automatic Weight Measurement of Pigs Based on 3D Images and Regression Network. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 187, 106299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiha, M.; Bahr, C.; Haredasht, S.A.; Ott, S.; Moons, C.P.H.; Niewold, T.A.; Ödberg, F.O.; Berckmans, D. Automatic Weight Estimation of Individual Pigs Using Image Analysis. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2014, 107, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, W.; Winter, P.; Walker, L. Walk-Through Weighing of Pigs Using Machine Vision and an Artificial Neural Network. Biosyst. Eng. 2008, 100, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Li, S.; Wu, Q. A Novel Supertwisting Zeroing Neural Network With Application to Mobile Robot Manipulators. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 32, 1776–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Y.; Pu, S.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, J.; Xing, W. Estimation of Sow Backfat Thickness Based on Machine Vision. Animals 2024, 14, 3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Yin, L.; Kuang, Y. A Novel Approach of Pig Weight Estimation Using High-Precision Segmentation and 2D Image Feature Extraction. Animals 2025, 15, 2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Zhao, W. Multi-View Fusion-Based Automated Full-Posture Cattle Body Size Measurement. Animals 2024, 14, 3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Bokkers, E.A.M.; van der Tol, P.P.J.; Groot Koerkamp, P.W.G.; van Mourik, S. Automated Body Condition Scoring of Dairy Cows Using 3-Dimensional Feature Extraction from Multiple Body Regions. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 4294–4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruchay, A.; Kober, V.; Dorofeev, K.; Kolpakov, V.; Miroshnikov, S. Accurate Body Measurement of Live Cattle Using Three Depth Cameras and Non-Rigid 3-D Shape Recovery. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 179, 105821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, S.; Ling, Y.; Shihao, L.; Haojie, Z.; Xuhong, T.; Caixing, L.; Aidong, S.; Hanxing, L. Research on 3D Surface Reconstruction and Body Size Measurement of Pigs Based on Multi-View RGB-D Cameras. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 175, 105543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputra, F.; Farhan, A.; Suryanto, M.E.; Kurnia, K.A.; Chen, K.H.C.; Vasquez, R.D.; Roldan, M.J.M.; Huang, J.-C.; Lin, Y.-K.; Hsiao, C.-D. Automated Cardiac Chamber Size and Cardiac Physiology Measurement in Water Fleas by U-Net and Mask RCNN Convolutional Networks. Animals 2022, 12, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzuolo, A.; Guarino, M.; Sartori, L.; González, L.A.; Marinello, F. On-Barn Pig Weight Estimation Based on Body Measurements by a Kinect v1 Depth Camera. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 148, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.; Park, A.; Lee, H.; Mun, D. Deep Learning-Based Weight Estimation Using a Fast-Reconstructed Mesh Model from the Point Cloud of a Pig. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 210, 107903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.H.; Holt, J.P.; Knauer, M.T.; Abner, V.A.; Lobaton, E.J.; Young, S.N. Towards Rapid Weight Assessment of Finishing Pigs Using a Handheld, Mobile RGB-D Camera. Biosyst. Eng. 2023, 226, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salau, J.; Haas, J.H.; Junge, W.; Thaller, G. Extrinsic Calibration of a Multi-Kinect Camera Scanning Passage for Measuring Functional Traits in Dairy Cows. Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 151, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viazzi, S.; Bahr, C.; Van Hertem, T.; Schlageter-Tello, A.; Romanini, C.E.B.; Halachmi, I.; Lokhorst, C.; Berckmans, D. Comparison of a Three-Dimensional and Two-Dimensional Camera System for Automated Measurement of Back Posture in Dairy Cows. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2014, 100, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brünger, J.; Gentz, M.; Traulsen, I.; Koch, R. Panoptic Segmentation of Individual Pigs for Posture Recognition. Sensors 2020, 20, 3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, N.; Antoine, V.; Mialon, M.-M.; Lardy, R.; Silberberg, M.; Koko, J.; Veissier, I. Machine Learning to Detect Behavioural Anomalies in Dairy Cows Under Subacute Ruminal Acidosis. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 170, 105233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measurement Dimension | Mean Absolute Error (MAE, cm) | Root Mean Square Error (RMSE, cm) | Coefficient of Determination (R2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Side-view Body Length | 4.2 | 5.6 | 0.914 |

| Top-view Body Length | 3.0 | 4.1 | 0.956 |

| Body Width | 1.9 | 2.3 | 0.942 |

| Body Height | 1.8 | 2.3 | 0.929 |

| Chest Girth | 4.6 | 5.8 | 0.906 |

| Top-view vs. Side-view Body Length | 5.0 | 6.4 | 0.893 |

| Model | MAE (kg) | RMSE (kg) | MAPE (%) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ramanujan ellipse | 3.24 | 4.20 | 6.33 | 0.9597 |

| Track-shaped approximation | 3.39 | 4.29 | 6.33 | 0.956 |

| Simple ellipse | 3.39 | 4.33 | 6.33 | 0.9572 |

| Pig-specific empirical formula | 3.39 | 4.33 | 6.33 | 0.9577 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ma, Z.; Li, S.; Ren, Z.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Chen, W.; Tang, H.; Gao, Y.; Li, Y.; Xing, B.; et al. Design and Verification of a Non-Contact Body Dimension Measurement System for Jiangquan Black Pigs Based on Dual-View Depth Vision. Animals 2025, 15, 3601. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243601

Ma Z, Li S, Ren Z, Wang J, Chen J, Chen W, Tang H, Gao Y, Li Y, Xing B, et al. Design and Verification of a Non-Contact Body Dimension Measurement System for Jiangquan Black Pigs Based on Dual-View Depth Vision. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3601. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243601

Chicago/Turabian StyleMa, Zhao, Shiyin Li, Zhanchi Ren, Jing Wang, Junfeng Chen, Wei Chen, Hui Tang, Yarui Gao, Yunpeng Li, Baosong Xing, and et al. 2025. "Design and Verification of a Non-Contact Body Dimension Measurement System for Jiangquan Black Pigs Based on Dual-View Depth Vision" Animals 15, no. 24: 3601. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243601

APA StyleMa, Z., Li, S., Ren, Z., Wang, J., Chen, J., Chen, W., Tang, H., Gao, Y., Li, Y., Xing, B., & Zeng, Y. (2025). Design and Verification of a Non-Contact Body Dimension Measurement System for Jiangquan Black Pigs Based on Dual-View Depth Vision. Animals, 15(24), 3601. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243601