Effects of Dietary Sunflower Hulls on Performance and Rumen Fermentation of Pregnant Naemi Ewes: A Sustainable Fiber Source for Arid Regions

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Experimental Animals and Management

2.3. Diets, Sunflower Hulls Source, and TMR Preparation

2.4. Feed Sampling and Chemical Analysis

2.5. Feed Intake and Body Weight Measurement

2.6. Body Condition Scores

2.7. Digestibility Trial and Analysis

2.8. Rumen Fermentation Profile

2.9. Blood Collection and Biochemical Analysis

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

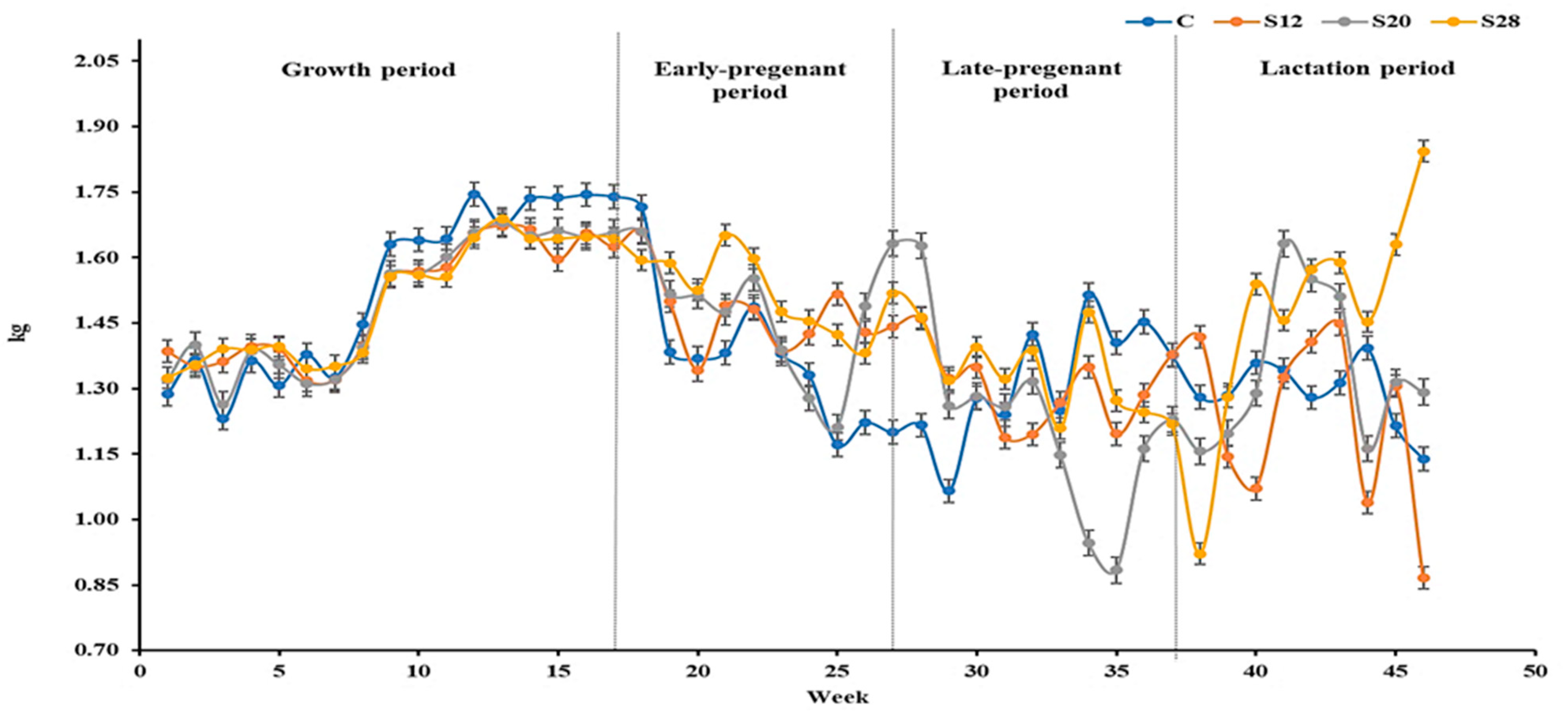

3.1. Ewes’ Performance and Body Condition Scores

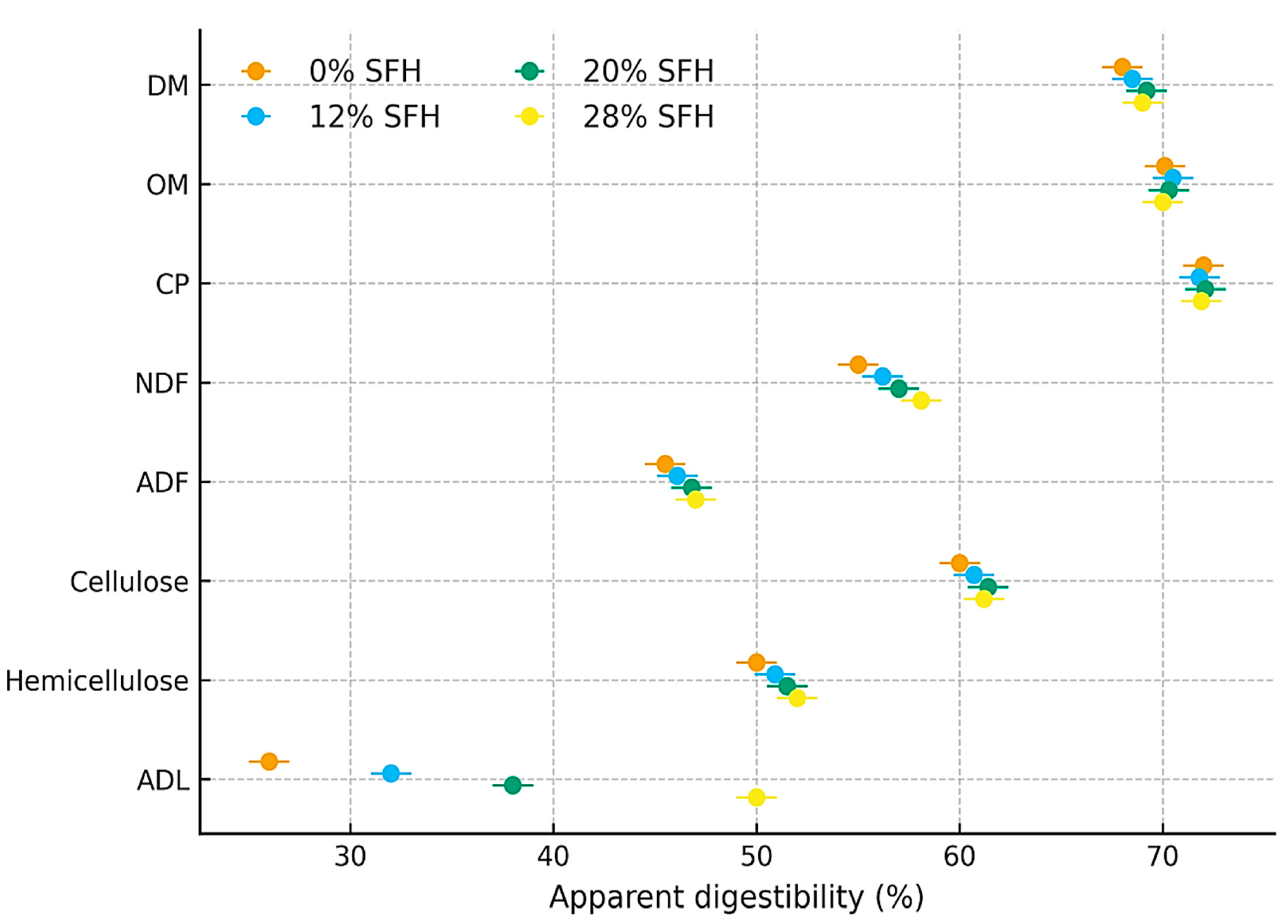

3.2. Digestibility Trial

3.3. Rumen Fermentation Pattern of Naemi Ewes

3.4. Serum Metabolic Profile of Ewes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ghorbel, M.; Alghamdi, A.; Brini, F.; Hawamda, A.I.; Mseddi, K. Mitigating water loss in arid lands: Buffelgrass as a potential replacement for alfalfa in livestock feed. Agronomy 2025, 15, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoharan, R.; Asthana, S.; Somanathan Nair, C.; Gokhale, T.; Nishanth, D.; Jaleel, A.; Sood, N. Exploring the hidden treasure in arid regions: Pseudocereals as sustainable, climate-resilient crops for food security. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1662267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alharthi, A.S.; Al-Baadani, H.H.; Al-Badwi, M.A.; Abdelrahman, M.M.; Alhidary, I.A.; Khan, R.U. Effects of sunflower hulls on productive performance, digestibility indices and rumen morphology of growing Awassi lambs fed with total mixed rations. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdoun, K.A.; Suliman, G.M.; Alsagan, A.A.; Altahir, O.A.; Alsaiady, M.Y.; Babiker, E.E.; Al-Badwi, M.A.; Alshamiry, F.A.; Al-Haidary, A.A. Replacing alfalfa-based total mixed ration with moringa leaves for improving carcass and meat quality characteristics in lambs. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Niekerk, J.W. Effect of Rumen-Specific Live Yeast Supplementation on In Situ Ruminal Degradation of Forages Differing in Nutritive Quality. Master’s Thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Habeeb, A. The healthy and nutritional benefits of adding flaxseed to farm animal feeding on nutrient utilization, blood biochemical components, productive and reproductive efficiency and sheep wool characteristics. Indiana J. Agric. Life Sci. 2025, 5, 7–23. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Wei, Z.; Guo, B.; Bai, R.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Sun, W.; Jiang, X.; Li, X.; Pi, Y. Flaxseed meal and its application in animal husbandry: A review. Agriculture 2022, 12, 2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas-Salazar, A.P.; Schoor, M.; Nieto-Ramírez, M.I.; García-Trejo, J.F.; Torres-Pacheco, I.; Guevara-González, R.G.; Aguirre-Becerra, H.; Feregrino-Pérez, A.A. Morphological and Nutritional Characterization of the Native Sunflower as a Potential Plant Resource for the Sierra Gorda of Querétaro. Resources 2025, 14, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z.T.; Singh, P.; Shankar, R.; Kumar, S.; Sarkar, D.; Shah, U.N.; Hassan, S. Unleashing the nutritional power of sunflower seeds, pumpkin seeds, chia seeds, flaxseeds, and hemp seeds. In Superfoods; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2026; pp. 99–128. [Google Scholar]

- Serrapica, F.; Masucci, F.; Raffrenato, E.; Sannino, M.; Vastolo, A.; Barone, C.M.A.; Di Francia, A. High fiber cakes from mediterranean multipurpose oilseeds as protein sources for ruminants. Animals 2019, 9, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.M.; Zhang, H.; Shahid, M.; Ghazal, H.; Shah, A.R.; Niaz, M.; Naz, T.; Ghimire, K.; Goswami, N.; Shi, W. The vital roles of agricultural crop residues and agro-industrial by-products to support sustainable livestock productivity in subtropical regions. Animals 2025, 15, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, G.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Effects of high forage/concentrate diet on volatile fatty acid production and the microorganisms involved in VFA production in cow rumen. Animals 2020, 10, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, N.S.; Khamil, I.A.M.; Sapawe, N. Proximate analysis of animal feed pellet formulated from sunflower shell waste. Mater. Today Proc. 2019, 19, 1796–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso-Gutiérrez, E.; Narváez-López, A.C.; Robles-Jiménez, L.E.; Morales Osorio, A.; Gutierrez-Martinez, M.d.G.; Leskinen, H.; Mele, M.; Vargas-Bello-Pérez, E.; González-Ronquillo, M. Production performance, nutrient digestibility, and milk composition of dairy ewes supplemented with crushed sunflower seeds and sunflower seed silage in corn silage-based diets. Animals 2020, 10, 2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas-Bello-Pérez, E.; Mustafa, A.; Seguin, P. Effects of feeding forage soybean silage on milk production, nutrient digestion, and ruminal fermentation of lactating dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2008, 91, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piccione, G.; Caola, G.; Giannetto, C.; Grasso, F.; Runzo, S.C.; Zumbo, A.; Pennisi, P. Selected biochemical serum parameters in ewes during pregnancy, post-parturition, lactation and dry period. Anim. Sci. Pap. Rep. 2009, 27, 321–330. [Google Scholar]

- Taghipour, B.; Seifi, H.A.; Mohri, M.; Farzaneh, N.; Naserian, A. Variations of energy related biochemical metabolites during periparturition period in fat-tailed baloochi breed sheep. Iran. J. Vet. Sci. Technol. 2010, 2, 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, W.; Jing, X.; Degen, A.; Guo, Y.; Kang, J.; Shang, Z.; Yu, Z.; Qiu, Q.; Guo, X. Effect of dietary energy on digestibilities, rumen fermentation, urinary purine derivatives and serum metabolites in Tibetan and small–tailed Han sheep. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2019, 103, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. Committee on Nutrient Requirements of Small Ruminants. In Nutrient Requirements of Small Ruminants: Sheep, Goats, Cervids, and New World Camelids; China Legal Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno, A.; Di Grigoli, A.; Vitale, F.; Di Miceli, G.; Todaro, M.; Alabiso, M.; Gargano, M.L.; Venturella, G.; Anike, F.N.; Isikhuemhen, O.S. Effects of diets supplemented with medicinal mushroom myceliated grains on some production, health, and oxidation traits of dairy ewes. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2019, 21, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, P.v.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santucci, P.; Maestrini, O. Body conditions of dairy goats in extensive systems of production: Method of estimation. Ann. Zootech. 1985, 34, 473–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, G.O.; Gruninger, R.J.; Jones, D.R.; Beauchemin, K.A.; Yang, W.Z.; Wang, Y.; Abbott, D.W.; Tsang, A.; McAllister, T.A. Effect of ammonia fiber expansion-treated wheat straw and a recombinant fibrolytic enzyme on rumen microbiota and fermentation parameters, total tract digestibility, and performance of lambs. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 98, skaa116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Lin, J.; Chen, Y.; Zang, C.; Yang, F.; Li, J.; Li, X. Effects of sodium acetate and sodium butyrate on the volatile compounds in mare’s milk based on gc-ims analysis. Animals 2025, 15, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SAS Institute. SAS/IML 9.3 User’s Guide, version 9.4; Sas Institute: Cary, NC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Alobre, M.M.; Abdelrahman, M.M.; Alhidary, I.A.; Matar, A.M.; Aljumaah, R.S.; Alhotan, R.A. Evaluating the effect of using different levels of sunflower hulls as a source of fiber in a complete feed on Naemi ewes’ Milk yield, composition, and fatty acid profile at 6, 45, and 90 days postpartum. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahgoub, O.; Kadim, I.T.; Al-Busaidi, M.H.; Annamalai, K.; Al-Saqri, N.M. Effects of feeding ensiled date palm fronds and a by-product concentrate on performance and meat quality of Omani sheep. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2007, 135, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, X.; Xie, K.; Pan, Y.; Liu, F.; Hou, F. Effects of different fiber levels of energy feeds on rumen fermentation and the microbial community structure of grazing sheep. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetanova, F.; Naydenova, G.; Boyadzhieva, S. Sunflower Seed Hulls and Meal—A Waste with Diverse Biotechnological Benefits. Biomass 2025, 5, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conghos, M.M.; Aguirre, M.E.; Santamaría, R.M. Biodegradation of sunflower hulls with different nitrogen sources under mesophilic and thermophilic incubations. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2003, 38, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simović, M.; Banjanac, K.; Veljković, M.; Nikolić, V.; López-Revenga, P.; Montilla, A.; Moreno, F.J.; Bezbradica, D. Sunflower meal valorization through enzyme-aided fractionation and the production of emerging prebiotics. Foods 2024, 13, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindson, J.; Winter, A. Manual of Sheep Diseases; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Balıkcı, E.; Yıldız, A.; Gürdoğan, F. Blood metabolite concentrations during pregnancy and postpartum in Akkaraman ewes. Small Rumin. Res. 2007, 67, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesántez-Pacheco, J.L.; Heras-Molina, A.; Torres-Rovira, L.; Sanz-Fernández, M.V.; García-Contreras, C.; Vázquez-Gómez, M.; Feyjoo, P.; Cáceres, E.; Frías-Mateo, M.; Hernández, F. Influence of maternal factors (weight, body condition, parity, and pregnancy rank) on plasma metabolites of dairy ewes and their lambs. Animals 2019, 9, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sherif, M.; Assad, F. Changes in some blood constituents of Barki ewes during pregnancy and lactation under semi arid conditions. Small Rumin. Res. 2001, 40, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannas, A.; Pes, A.; Mancuso, R.; Vodret, B.; Nudda, A. Effect of dietary energy and protein concentration on the concentration of milk urea nitrogen in dairy ewes. J. Dairy Sci. 1998, 81, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Sunflower Hull Level Treatments 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% | 12% | 20% | 28% | |

| Ingredients (% of dietary dry matter) | ||||

| Barley grain | 32.56 | 20.41 | 22.21 | 29.20 |

| Palm kernel meal | 20.00 | 20.00 | 20.00 | 9.25 |

| Wheat straw | 16.30 | 16.33 | 6.51 | 0.00 |

| Sunflower meal | 13.80 | 13.84 | 13.71 | 16.03 |

| Sunflower hulls | 0.00 | 12.00 | 20.00 | 28.00 |

| Wheat bran | 10.00 | 10.00 | 10.00 | 10.00 |

| Molasses | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| Acid buffer | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| Limestone | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.87 | 0.90 |

| Salt | 0.52 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.49 |

| Vitamin and mineral premix | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Chemical composition, % dry matter basis | ||||

| Dry matter | 90.39 | 88.47 | 88.74 | 88.54 |

| Protein | 14.86 | 14.55 | 14.18 | 14.98 |

| Fiber | 18.26 | 20.78 | 22.16 | 21.81 |

| Ash | 14.25 | 6.61 | 6.34 | 5.88 |

| Fat | 4.02 | 4.35 | 4.35 | 4.00 |

| Salt | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| ADF | 28.46 | 30.25 | 30.66 | 29.55 |

| NDF | 36.50 | 37.59 | 39.74 | 41.52 |

| Lignin | 7.37 | 6.99 | 8.88 | 9.07 |

| Cellulose | 19.77 | 21.35 | 18.51 | 21.06 |

| Hemicellulose | 6.96 | 8.49 | 9.13 | 10.87 |

| Gross energy (Cal/g) | 3641 | 3613 | 3710 | 3744 |

| Nutritive values of SFH based on NRC | ||||

| Chemical composition,% dry matter basis | Sunflower hulls (%) | |||

| Dry matter | 90.00 | |||

| Crude Protein | 4.00 | |||

| Crude fiber | 52.00 | |||

| NDF | 73.00 | |||

| ADF | 63.45 | |||

| Acid detergent lignin | 22.01 | |||

| Ether extract | 2.20 | |||

| Ash | 3.00 | |||

| Calcium | 1.47 | |||

| Phosphorus | 0.11 | |||

| ME (Mcal/kg) | 1.4 | |||

| Measurement, Unit | Sunflower Hull Level Treatments 1 | SEM 2 | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% | 12% | 20% | 28% | |||

| Feed intake, kg/d | ||||||

| Growth | 1.51 a | 1.49 ab | 1.48 b | 1.49 ab | 0.01 | 0.05 C |

| Early gestation | 1.37 c | 1.48 b | 1.53 a | 1.54 a | 0.03 | 0.01 Q |

| Late gestation | 1.31 ab | 1.26 b | 1.18 c | 1.36 a | 0.01 | 0.01 Q |

| Lactation | 1.34 b | 1.17 c | 1.31 b | 1.50 a | 0.02 | 0.01 Q |

| Overall | 1.34 b | 1.35 b | 1.37 b | 1.47 a | 0.02 | 0.02 P, T*P |

| Body weight, kg | ||||||

| Growth | 41.75 | 41.63 | 42.02 | 41.86 | 0.31 | 0.97 |

| Early gestation | 50.76 | 51.09 | 50.51 | 50.25 | 0.40 | 0.89 |

| Late gestation | 58.25 | 59.88 | 58.78 | 61.01 | 0.46 | 0.16 |

| Lactation | 59.91 | 58.14 | 57.38 | 59.23 | 0.87 | 0.76 |

| Overall | 52.67 | 52.67 | 52.67 | 52.67 | 0.51 | 0.69 |

| Body condition score | ||||||

| Late gestation | 3.40 a | 3.31 a | 3.00 b | 3.16 b | 0.35 | 0.05 Q |

| Lactation | 2.75 ab | 2.68 ab | 2.31 c | 2.90 a | 0.16 | 0.04 Q |

| Overall | 3.07 | 3.00 | 2.65 | 2.83 | 0.08 | 0.12 |

| Measurement, Unit | Sunflower Hull Level Treatments 1 | SEM | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% | 12% | 20% | 28% | |||

| pH value | ||||||

| Prepartum, 30 d | 6.38 b | 6.47 ab | 6.57 ab | 6.90 a | 0.28 | 0.01 L |

| Postpartum, 30 d | 6.06 | 6.12 | 6.06 | 6.07 | 0.35 | 0.70 |

| Overall | 6.22 | 6.30 | 6.32 | 6.49 | 0.05 | 0.86 P, T*P |

| Total VFAs, mM | ||||||

| Prepartum, 30 d | 114.38 a | 94.94 ab | 75.50 bc | 57.53 c | 7.17 | 0.01 L |

| Postpartum, 30 d | 102.67 a | 58.47 b | 62.15 b | 67.32 b | 7.07 | 0.006 L |

| Overall | 108.53 | 76.71 | 68.83 | 62.43 | 5.00 | 0.001 P, T*P |

| Acetate, mM | ||||||

| Prepartum, 30 d | 54.70 a | 46.15 a | 30.38 b | 28.75 b | 3.38 | 0.04 L |

| Postpartum, 30 d | 50.14 a | 27.21 b | 31.13 b | 35.17 ab | 3.56 | 0.001 L |

| Overall | 52.42 | 36.68 | 30.755 | 31.96 | 2.56 | 0.001 |

| Propionate, mM | ||||||

| Prepartum, 30 d | 28.50 a | 24.15 ab | 22.68 b | 16.21 b | 2.06 | 0.05 L |

| Postpartum, 30 d | 31.55 a | 17.10 b | 16.64 b | 17.31 b | 1.97 | 0.002 L |

| Overall | 30.03 | 20.63 | 19.66 | 16.76 | 1.36 | 0.001 T*P |

| Butyrate, mM | ||||||

| Prepartum, 30 d | 22.47 a | 20.48 ab | 13.97 b | 5.65 c | 1.83 | 0.01 L |

| Postpartum, 30 d | 17.82 a | 14.15 b | 12.50 ab | 11.22 ab | 1.72 | 0.05 L |

| Overall | 20.15 | 17.32 | 13.24 | 8.44 | 1.27 | 0.001 |

| Valerate, mM | ||||||

| Prepartum, 30 d | 2.55 a | 2.17 ab | 1.87 cb | 1.36 c | 1.13 | 0.01 L |

| Postpartum, 30 d | 2.17 a | 1.29 b | 1.98 a | 1.24 b | 0.12 | 0.001 |

| Overall | 2.36 | 1.73 | 1.93 | 1.30 | 0.09 | 0.001 P, T*P |

| Acetate: Propionate ratio | ||||||

| Prepartum, 30 d | 1.98 b | 2.07 b | 1.26 b | 1.77 a | 0.20 | 0.02 Q |

| Postpartum, 30 d | 1.56 ab | 1.59 b | 1.87 ab | 2.03 a | 0.15 | 0.05 Q |

| Overall | 1.77 | 1.83 | 1.26 | 1.87 | 0.12 | 0.03 P, T*P |

| Measurement, Unit | Treatments Based on Sunflower Hull Levels 1 | SEM 2 | p Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% | 12% | 20% | 28% | |||

| Glucose mg/dL | ||||||

| Growth | 38.55 b | 49.74 ab | 40.04 b | 53.38 a | 2.25 | 0.04 C |

| Pregnant | 48.40 a | 48.78 a | 46.32 ab | 33.73 b | 2.45 | 0.05 L |

| Lactation | 68.95 | 72.99 | 74.54 | 59.80 | 3.70 | 0.48 |

| Overall | 51.96 | 57.17 | 53.63 | 48.97 | 2.03 | 0.33 P |

| Total protein g/dL | ||||||

| Growth | 6.58 | 6.59 | 6.32 | 6.52 | 0.09 | 0.70 |

| Pregnant | 6.75 a | 6.67 b | 6.71 ab | 6.33 d | 0.03 | 0.001 C |

| Lactation | 6.56 c | 7.01 a | 7.01 a | 6.92 b | 0.04 | 0.01 Q |

| Overall | 6.63 ab | 6.75 a | 6.68 ab | 6.59 b | 0.04 | 0.05 Q P, T*P |

| Albumin g/dL | ||||||

| Growth | 3.00 b | 3.50 b | 4.28 a | 4.66 a | 0.23 | 0.04 L |

| Pregnant | 4.12 | 3.54 | 4.19 | 4.50 | 0.20 | 0.37 |

| Lactation | 3.90 | 3.36 | 2.80 | 2.98 | 0.20 | 0.18 |

| Overall | 3.67 | 3.47 | 3.75 | 4.04 | 0.13 | 0.38 P, T*P |

| Total cholesterol mg/dL | ||||||

| Growth | 61.60 | 57.96 | 58.01 | 61.30 | 2.29 | 0.91 |

| Pregnant | 70.27 b | 65.05 c | 75.12 a | 74.86 ab | 0.79 | 0.001 C |

| Lactation | 88.50 b | 98.51 a | 98.30 a | 78.00 c | 1.63 | 0.01 Q |

| Overall | 73.45 ab | 73.84 ab | 77.21 a | 71.38 b | 1.71 | 0.05 Q P, T*P |

| Triglyceride’s mg/dL | ||||||

| Growth | 49.70 | 49.65 | 45.00 | 46.48 | 1.53 | 0.64 |

| Pregnant | 53.75 d | 56.15 c | 58.47 b | 59.27 ab | 1.06 | 0.001 L |

| Lactation | 58.61 b | 60.45 a | 60.45 a | 49.99 c | 0.83 | 0.001 Q |

| Overall | 54.02 ab | 56.65 a | 54.79 ab | 51.91 b | 0.79 | 0.01 Q P, T*P |

| Urea-N mg/dL | ||||||

| Growth | 24.35 a | 20.13 cb | 22.11 ab | 19.81 c | 0.95 | 0.03 C |

| Pregnant | 15.92 c | 16.18 b | 16.09 bc | 20.01 a | 0.33 | 0.001 L |

| Lactation | 21.13 b | 21.82 a | 21.82 a | 20.94 c | 0.07 | 0.01 Q |

| Overall | 20.52 | 19.52 | 20.00 | 20.25 | 0.42 | 0.63 P, T*P |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alobre, M.M.; Alhidary, I.A.; Qaid, M.M.; Alharthi, A.S.; Aboragah, A.A.; Aljumaah, R.S.; Abdelrahman, M.M. Effects of Dietary Sunflower Hulls on Performance and Rumen Fermentation of Pregnant Naemi Ewes: A Sustainable Fiber Source for Arid Regions. Animals 2025, 15, 3569. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243569

Alobre MM, Alhidary IA, Qaid MM, Alharthi AS, Aboragah AA, Aljumaah RS, Abdelrahman MM. Effects of Dietary Sunflower Hulls on Performance and Rumen Fermentation of Pregnant Naemi Ewes: A Sustainable Fiber Source for Arid Regions. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3569. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243569

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlobre, Mohsen M., Ibrahim A. Alhidary, Mohammed M. Qaid, Abdulrahman S. Alharthi, Ahmad A. Aboragah, Riyadh S. Aljumaah, and Mutassim M. Abdelrahman. 2025. "Effects of Dietary Sunflower Hulls on Performance and Rumen Fermentation of Pregnant Naemi Ewes: A Sustainable Fiber Source for Arid Regions" Animals 15, no. 24: 3569. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243569

APA StyleAlobre, M. M., Alhidary, I. A., Qaid, M. M., Alharthi, A. S., Aboragah, A. A., Aljumaah, R. S., & Abdelrahman, M. M. (2025). Effects of Dietary Sunflower Hulls on Performance and Rumen Fermentation of Pregnant Naemi Ewes: A Sustainable Fiber Source for Arid Regions. Animals, 15(24), 3569. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243569