Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Pentapodus caninus and Lethrinus olivaceus (Spariformes: Nemipteridae and Lethrinidae): Genome Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Genomic DNA Isolation

2.2. Amplification and Sequencing of Mitochondrial Genomes

2.3. Mitochondrial Genome Assembly

2.4. Comparative Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Mitogenomic Architecture and Base Composition

3.2. Analysis of Protein-Coding Sequences

3.3. Codon Usage Patterns and Amino Acid Frequency

3.4. Characterization of RNA Genes

3.4.1. rRNA Genes

3.4.2. General Features of tRNA Genes

3.4.3. Tandem Duplication of tRNA-Val in L. olivaceus

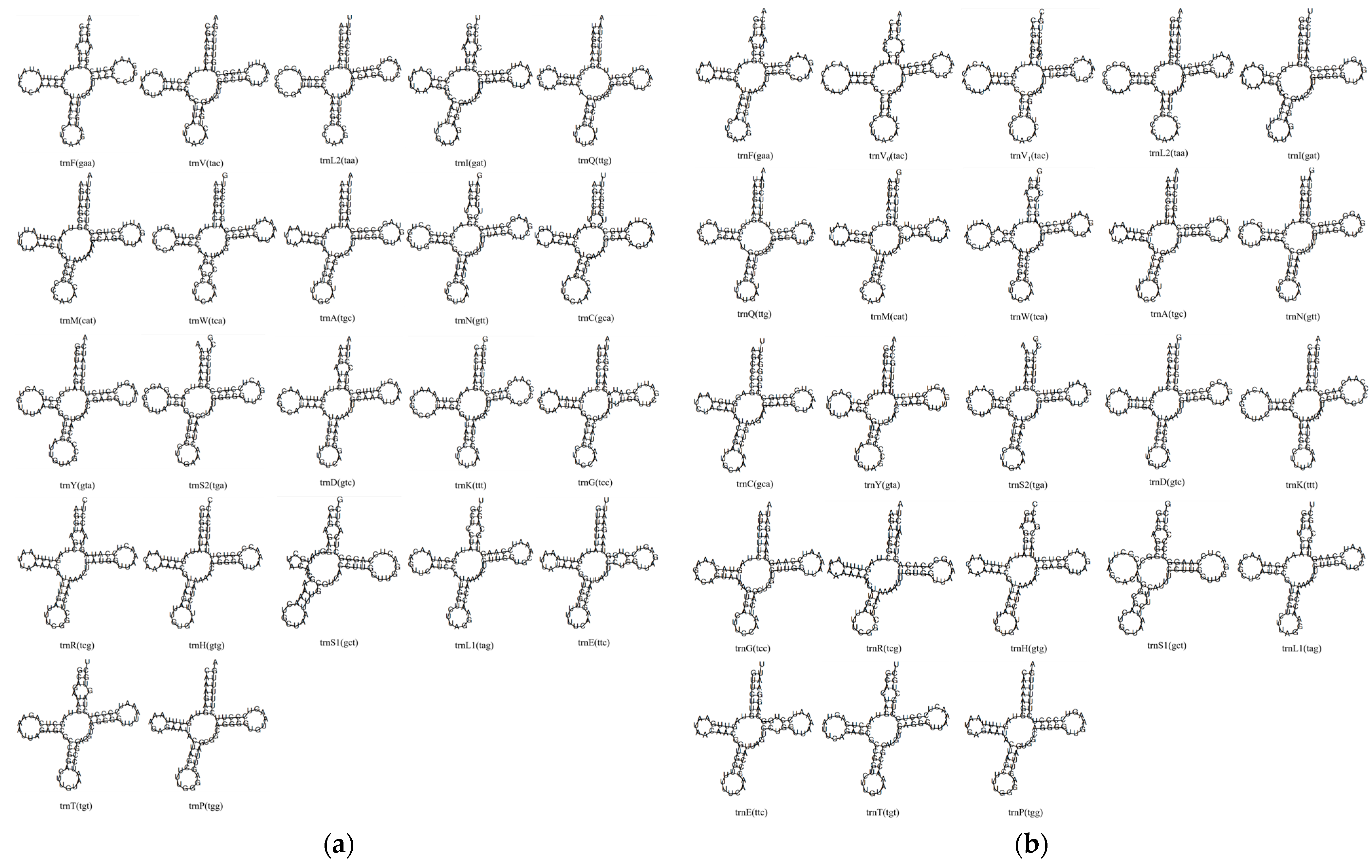

3.4.4. tRNA Secondary Structures

3.5. Characteristics of Control Region

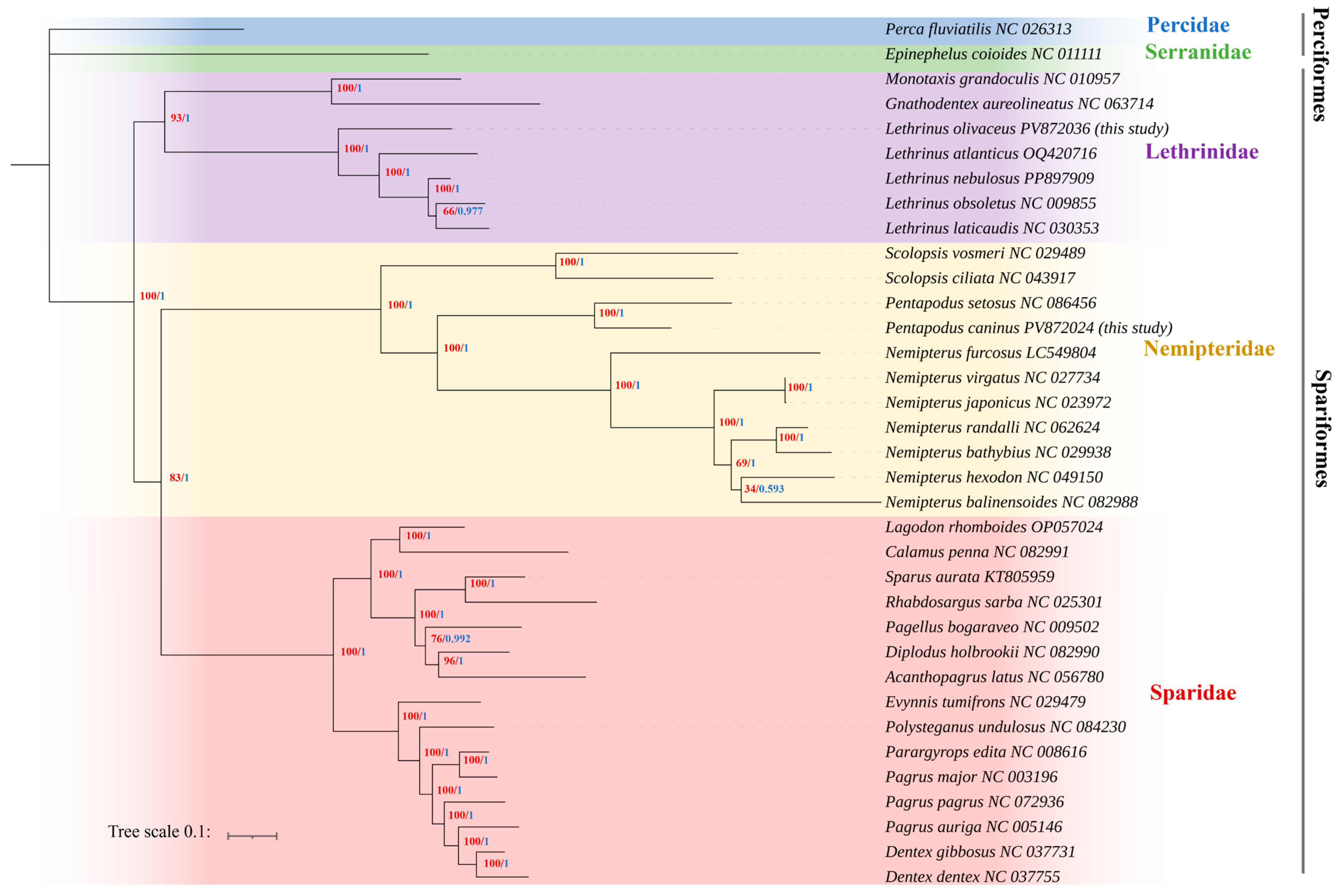

3.6. Phylogenetic Relationships

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCGs | Protein-coding genes |

| tRNA | Transfer RNA |

| rRNA | RibosomalRNA |

| RSCU | Relative synonymous codon usage |

| ML | Maximum likelihood |

| BI | Bayesian inference |

| DHU | Dihydrouridine |

| D-loop | Non-coding control region |

| TAS | Termination-associated sequence |

References

- Betancur-R, R.; Wiley, E.O.; Arratia, G.; Acero, A.; Bailly, N.; Miya, M.; Lecointre, G.; Orti, G. Phylogenetic classification of bony fishes. BMC Evol. Biol. 2017, 17, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, J.S.; Grande, T.C.; Wilson, M.V. Fishes of the World; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanciangco, M.D.; Carpenter, K.E.; Betancur-R, R. Phylogenetic placement of enigmatic percomorph families (Teleostei: Percomorphaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2016, 94, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carpenter, K.E.; Johnson, G.D. A phylogeny of sparoid fishes (Perciformes, Percoidei) based on morphology. Ichthyol. Res. 2002, 49, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, J.J. Phylogenetic relationships of the Sparidae (Teleostei: Percoidei) and implications for convergent trophic evolution. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2002, 76, 269–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Johnson, G.D. The Limits and Relationships of the Lutjanidae and Associated Families; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Natsidis, P.; Tsakogiannis, A.; Pavlidis, P.; Tsigenopoulos, C.S.; Manousaki, T. Phylogenomics investigation of sparids (Teleostei: Spariformes) using high-quality proteomes highlights the importance of taxon sampling. Commun. Biol. 2019, 2, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damadi, E.; Moghaddam, F.Y.; Ghanbarifardi, M. Taxonomic characterization of five species of emperor fishes (Actinopterygii: Eupercaria: Lethrinidae) based on external morphology, morphometry, and geographic distribution in the northwestern Indian Ocean. Acta Ichthyol. Piscat. 2024, 54, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabian, V.; Houk, P.; Lemer, S. Phylogeny of Micronesian emperor fishes and evolution of trophic types. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2021, 162, 107207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, K.E. FAO Species Catalogue. v. 9: Emperor Fishes and Largeeye Breams of the World (Family Lethrinidae); Food & Agriculture Org.: Rome, Italy, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, B.C. Nemipterid fishes of the world. FAO Fish. Synop. 1990, 12, I. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, B.W.; Rocha, L.A.; Toonen, R.J.; Karl, S.A. The origins of tropical marine biodiversity. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2013, 28, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miya, M.; Takeshima, H.; Endo, H.; Ishiguro, N.B.; Inoue, J.G.; Mukai, T.; Satoh, T.P.; Yamaguchi, M.; Kawaguchi, A.; Mabuchi, K. Major patterns of higher teleostean phylogenies: A new perspective based on 100 complete mitochondrial DNA sequences. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2003, 26, 121–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Borsa, P. Diversity, phylogeny, and historical biogeography of large-eye seabreams (Teleostei: Lethrinidae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2020, 151, 106902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Froese, R.; Pauly, D. FishBase. World Wide Web Electronic Publication. Version (04/2025). Available online: www.fishbase.org (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Schoch, C.L.; Ciufo, S.; Domrachev, M.; Hotton, C.L.; Kannan, S.; Khovanskaya, R.; Leipe, D.; Mcveigh, R.; O Neill, K.; Robbertse, B. NCBI Taxonomy: A comprehensive update on curation, resources and tools. Database 2020, 2020, a62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Galbo, A.M.; Carpenter, K.E.; Reed, D.L. Evolution of trophic types in emperor fishes (Lethrinus, Lethrinidae, Percoidei) based on cytochrome b gene sequence variation. J. Mol. Evol. 2002, 54, 754–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hung, K.W.; Russell, B.C.; Chen, W.J. Molecular systematics of threadfin breams and relatives (Teleostei, Nemipteridae). Zool. Scr. 2017, 46, 536–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogwang, J.; Bariche, M.; Bos, A.R. Genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationships of threadfin breams (Nemipterus spp.) from the Red Sea and eastern Mediterranean Sea. Genome 2021, 64, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wujdi, A.; Ewusi, E.O.M.; Sektiana, S.P.; Amin, M.H.F.A.; López-Vera, E.; Kim, H.; Kang, H.; Kundu, S. Mitogenomic characterization and phylogenetic placement of the Red pandora Pagellus bellottii from the Eastern Atlantic Ocean within the family Sparidae. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 30432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Cao, R.; Dong, Y.; Gao, X.; Cen, J.; Lu, S. The first complete mitochondrial genome of the flathead Cociella crocodilus (Scorpaeniformes: Platycephalidae) and the phylogenetic relationships within Scorpaeniformes based on whole mitogenomes. Genes 2019, 10, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Dong, Y.; Cao, R.; Zhou, X.; Lu, S. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome of Arius dispar (Siluriformes: Ariidae) and phylogenetic analysis among sea catfishes. J. Ocean Univ. China 2020, 19, 1198–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernt, M.; Donath, A.; Jühling, F.; Externbrink, F.; Florentz, C.; Fritzsch, G.; Pütz, J.; Middendorf, M.; Stadler, P.F. MITOS: Improved de novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2013, 69, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, W.; Fukunaga, T.; Isagozawa, R.; Yamada, K.; Maeda, Y.; Satoh, T.P.; Sado, T.; Mabuchi, K.; Takeshima, H.; Miya, M. MitoFish and MitoAnnotator: A mitochondrial genome database of fish with an accurate and automatic annotation pipeline. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 2531–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuter, J.S.; Mathews, D.H. RNAstructure: Software for RNA secondary structure prediction and analysis. BMC Bioinform. 2010, 11, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capella-Gutiérrez, S.; Silla-Martínez, J.M.; Gabaldón, T. trimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1972–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B.Q.; Wong, T.K.; Von Haeseler, A.; Jermiin, L.S. ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posada, D. jModelTest: Phylogenetic model averaging. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2008, 25, 1253–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Gao, F.; Jakovlić, I.; Zou, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.X.; Wang, G.T. PhyloSuite: An integrated and scalable desktop platform for streamlined molecular sequence data management and evolutionary phylogenetics studies. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2020, 20, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: Recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W78–W82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boore, J.L. Animal mitochondrial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 1767–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, S.; Kang, H.; Go, Y.; Bang, G.; Jang, Y.; Htoo, H.; Aini, S.; Kim, H. Mitogenomic architecture of Atlantic emperor Lethrinus atlanticus (Actinopterygii: Spariformes): Insights into the lineage diversification in Atlantic Ocean. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perna, N.T.; Kocher, T.D. Patterns of nucleotide composition at fourfold degenerate sites of animal mitochondrial genomes. J. Mol. Evol. 1995, 41, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miya, M.; Kawaguchi, A.; Nishida, M. Mitogenomic exploration of higher teleostean phylogenies: A case study for moderate-scale evolutionary genomics with 38 newly determined complete mitochondrial DNA sequences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2001, 18, 1993–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taanman, J. The mitochondrial genome: Structure, transcription, translation and replication. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Bioenerg. 1999, 1410, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanin, A.; Leger, N.; Deutsch, J. Evidence for multiple reversals of asymmetric mutational constraints during the evolution of the mitochondrial genome of Metazoa, and consequences for phylogenetic inferences. Syst. Biol. 2005, 54, 277–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macey, J.R.; Larson, A.; Ananjeva, N.B.; Fang, Z.; Papenfuss, T.J. Two novel gene orders and the role of light-strand replication in rearrangement of the vertebrate mitochondrial genome. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1997, 14, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, D.; Montoya, J.; Attardi, G. tRNA punctuation model of RNA processing in human mitochondria. Nature 1981, 290, 470–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabuchi, K.; Miya, M.; Satoh, T.P.; Westneat, M.W.; Nishida, M. Gene rearrangements and evolution of tRNA pseudogenes in the mitochondrial genome of the parrotfish (Teleostei: Perciformes: Scaridae). J. Mol. Evol. 2004, 59, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formenti, G.; Rhie, A.; Balacco, J.; Haase, B.; Mountcastle, J.; Fedrigo, O.; Brown, S.; Capodiferro, M.R.; Al-Ajli, F.O.; Ambrosini, R. Complete vertebrate mitogenomes reveal widespread repeats and gene duplications. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarenga, M.; D Elia, A.K.P.; Rocha, G.; Arantes, C.A.; Henning, F.; de Vasconcelos, A.T.R.; Solé-Cava, A.M. Mitochondrial genome structure and composition in 70 fishes: A key resource for fisheries management in the South Atlantic. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panja, A.S. The systematic codon usage bias has an important effect on genetic adaption in native species. Gene 2024, 926, 148627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Suematsu, T.; Ohtsuki, T. Losing the stem-loop structure from metazoan mitochondrial tRNAs and co-evolution of interacting factors. Front. Genet. 2014, 5, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Position | Size | Strand | Spacer (+) /Overlap (−) | Start/Stop Codon | AntiCodon | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | End | ||||||

| tRNA-Phe | 1 | 71 | 71 | H | 0 | - | GAA |

| 12S rRNA | 72 | 1068 | 997 | H | 2 | - | - |

| tRNA-Val | 1071 | 1142 | 72 | H | 22 | - | TAC |

| 16S rRNA | 1165 | 2869 | 1705 | H | 1 | - | - |

| tRNA-LeuUUR | 2871 | 2944 | 74 | H | 0 | - | TAA |

| ND1 | 2945 | 3919 | 975 | H | 4 | ATG/TAA | - |

| tRNA-Ile | 3924 | 3993 | 70 | H | −1 | - | GAT |

| tRNA-Gln | 3993 | 4063 | 71 | L | −1 | - | TTG |

| tRNA-Met | 4063 | 4132 | 70 | H | 0 | - | CAT |

| ND2 | 4133 | 5179 | 1047 | H | −1 | ATG/TAA | - |

| tRNA-Trp | 5179 | 5250 | 72 | H | 0 | - | TCA |

| tRNA-Ala | 5251 | 5319 | 69 | L | 2 | - | TGC |

| tRNA-Asn | 5322 | 5394 | 73 | L | 34 | - | GTT |

| tRNA-Cys | 5429 | 5497 | 69 | L | 0 | - | GCA |

| tRNA-Tyr | 5498 | 5568 | 71 | L | 1 | - | GTA |

| COX1 | 5570 | 7120 | 1551 | H | 1 | GTG/TAA | - |

| tRNA-SerUCN | 7122 | 7192 | 71 | L | 2 | - | TGA |

| tRNA-Asp | 7195 | 7266 | 72 | H | 7 | - | GTC |

| COX2 | 7274 | 7964 | 691 | H | 0 | ATG/T-- | - |

| tRNA-Lys | 7965 | 8039 | 75 | H | 1 | - | TTT |

| ATP8 | 8041 | 8208 | 168 | H | −10 | ATG/TAA | - |

| ATP6 | 8199 | 8882 | 684 | H | −1 | ATG/TAA | - |

| COX3 | 8882 | 9667 | 786 | H | −1 | ATG/TAA | - |

| tRNA-Gly | 9667 | 9737 | 71 | H | 0 | - | TCC |

| ND3 | 9738 | 10,088 | 351 | H | −2 | ATG/TAG | - |

| tRNA-Arg | 10,087 | 10,155 | 69 | H | 0 | - | TCG |

| ND4L | 10,156 | 10,452 | 297 | H | −7 | ATG/TAA | - |

| ND4 | 10,446 | 11,826 | 1381 | H | 0 | ATG/T-- | - |

| tRNA-His | 11,827 | 11,895 | 69 | H | 0 | - | GTG |

| tRNA-SerAGY | 11,896 | 11,962 | 67 | H | 3 | - | GCT |

| tRNA-LeuCUN | 11,966 | 12,038 | 73 | H | 0 | - | TAG |

| ND5 | 12,039 | 13,877 | 1839 | H | −4 | ATG/TAA | - |

| ND6 | 13,874 | 14,395 | 522 | L | 1 | ATG/TAA | - |

| tRNA-Glu | 14,397 | 14,465 | 69 | L | 4 | - | TTC |

| CYTB | 14,470 | 15,610 | 1141 | H | 0 | ATG/T-- | - |

| tRNA-Thr | 15,611 | 15,684 | 74 | H | −1 | - | TGT |

| tRNA-Pro | 15,684 | 15,752 | 69 | L | 1 | - | TGG |

| D-loop | 15,753 | 16,866 | 1114 | H | 0 | - | - |

| Feature | Position | Size | Strand | Spacer (+) /Overlap (−) | Start/Stop Codon | AntiCodon | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | End | ||||||

| tRNA-Phe | 1 | 68 | 68 | H | 0 | - | GAA |

| 12S rRNA | 69 | 1023 | 955 | H | 1 | - | - |

| tRNA-Val0 | 1025 | 1098 | 74 | H | 13 | - | TAC |

| tRNA-Val1 | 1112 | 1186 | 75 | H | 39 | TAC | |

| 16S rRNA | 1226 | 2894 | 1669 | H | 5 | - | - |

| tRNA-LeuUUR | 2900 | 2973 | 74 | H | 0 | - | TAA |

| ND1 | 2974 | 3945 | 972 | H | 4 | ATG/TAG | - |

| tRNA-Ile | 3950 | 4019 | 70 | H | −1 | - | GAT |

| tRNA-Gln | 4019 | 4089 | 71 | L | −1 | - | TTG |

| tRNA-Met | 4089 | 4158 | 70 | H | 0 | - | CAT |

| ND2 | 4159 | 5205 | 1047 | H | −1 | ATG/TAA | - |

| tRNA-Trp | 5205 | 5277 | 73 | H | 0 | - | TCA |

| tRNA-Ala | 5278 | 5346 | 69 | L | 1 | - | TGC |

| tRNA-Asn | 5348 | 5420 | 73 | L | 37 | - | GTT |

| tRNA-Cys | 5458 | 5526 | 69 | L | 0 | - | GCA |

| tRNA-Tyr | 5527 | 5596 | 70 | L | 1 | - | GTA |

| COX1 | 5598 | 7148 | 1551 | H | 1 | GTG/TAG | - |

| tRNA-SerUCN | 7150 | 7220 | 71 | L | 3 | - | TGA |

| tRNA-Asp | 7224 | 7295 | 72 | H | 7 | - | GTC |

| COX2 | 7303 | 7993 | 691 | H | 0 | ATG/T-- | - |

| tRNA-Lys | 7994 | 8069 | 76 | H | 1 | - | TTT |

| ATP8 | 8071 | 8238 | 168 | H | 13 | ATG/TAA | - |

| ATP6 | 8252 | 8935 | 684 | H | −1 | ATG/TAA | - |

| COX3 | 8935 | 9720 | 786 | H | −1 | ATG/TAA | - |

| tRNA-Gly | 9720 | 9790 | 71 | H | 0 | - | TCC |

| ND3 | 9791 | 10,141 | 351 | H | −2 | ATG/TAG | - |

| tRNA-Arg | 10,140 | 10,208 | 69 | H | 0 | - | TCG |

| ND4L | 10,209 | 10,505 | 297 | H | −7 | ATG/TAA | - |

| ND4 | 10,499 | 11,879 | 1381 | H | 0 | ATG/T-- | - |

| tRNA-His | 11,880 | 11,948 | 69 | H | 0 | - | GTG |

| tRNA-SerAGY | 11,949 | 12,018 | 70 | H | 5 | - | GCT |

| tRNA-LeuCUN | 12,024 | 12,096 | 73 | H | 0 | - | TAG |

| ND5 | 12,097 | 13,935 | 1839 | H | −4 | ATG/TAG | - |

| ND6 | 13,932 | 14,453 | 522 | L | 0 | ATG/TAG | - |

| tRNA-Glu | 14,454 | 14,522 | 69 | L | 4 | - | TTC |

| CYTB | 14,527 | 15,667 | 1141 | H | 0 | ATG/T-- | - |

| tRNA-Thr | 15,668 | 15,740 | 73 | H | −1 | - | TGT |

| tRNA-Pro | 15,740 | 15,808 | 69 | L | 1 | - | TGG |

| D-loop | 15,809 | 16,792 | 984 | H | 0 | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, N.; Gu, M.; Jiang, W.; Xie, L.; Qiao, Q.; Cen, J.; Dong, Y.; Lu, S.; Cui, L. Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Pentapodus caninus and Lethrinus olivaceus (Spariformes: Nemipteridae and Lethrinidae): Genome Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis. Animals 2025, 15, 3526. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243526

Chen N, Gu M, Jiang W, Xie L, Qiao Q, Cen J, Dong Y, Lu S, Cui L. Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Pentapodus caninus and Lethrinus olivaceus (Spariformes: Nemipteridae and Lethrinidae): Genome Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3526. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243526

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Nan, Mingcan Gu, Wenqing Jiang, Lei Xie, Qi Qiao, Jingyi Cen, Yuelei Dong, Songhui Lu, and Lei Cui. 2025. "Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Pentapodus caninus and Lethrinus olivaceus (Spariformes: Nemipteridae and Lethrinidae): Genome Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis" Animals 15, no. 24: 3526. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243526

APA StyleChen, N., Gu, M., Jiang, W., Xie, L., Qiao, Q., Cen, J., Dong, Y., Lu, S., & Cui, L. (2025). Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Pentapodus caninus and Lethrinus olivaceus (Spariformes: Nemipteridae and Lethrinidae): Genome Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis. Animals, 15(24), 3526. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243526