A20 Attenuates Inflammatory Injury in Bovine Endometrial Epithelial Cells Through Autophagy-Mediated NLRP3 Inflammasome Inactivation

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Antibodies and Reagents

2.2. BEECs Isolation and Treatments

2.3. LDH Release Assay

2.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.5. Caspase-1 Activity Assays

2.6. Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase-PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.7. Western Blotting

2.8. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

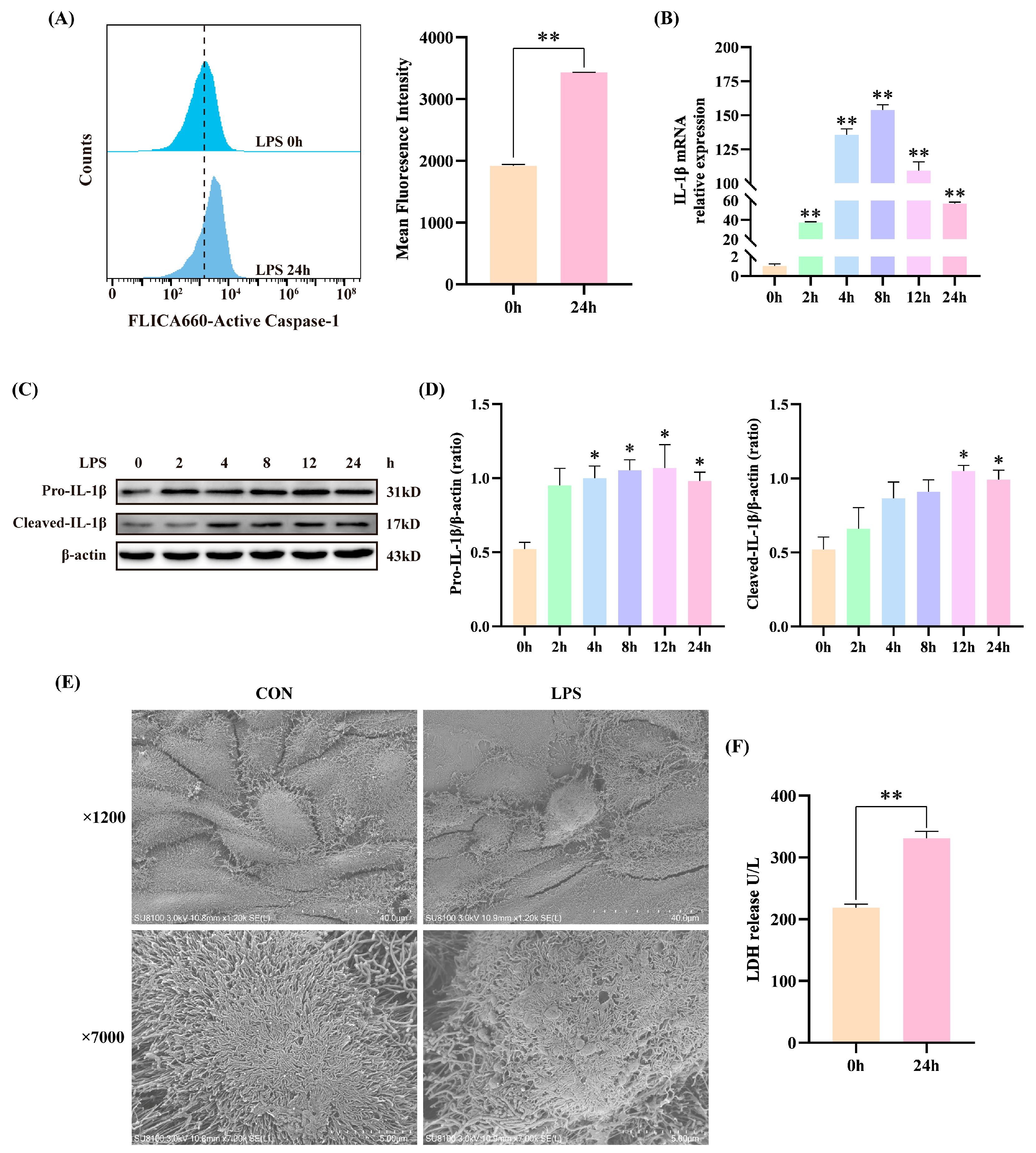

3.1. LPS Induced Inflammatory Injury in BEECs

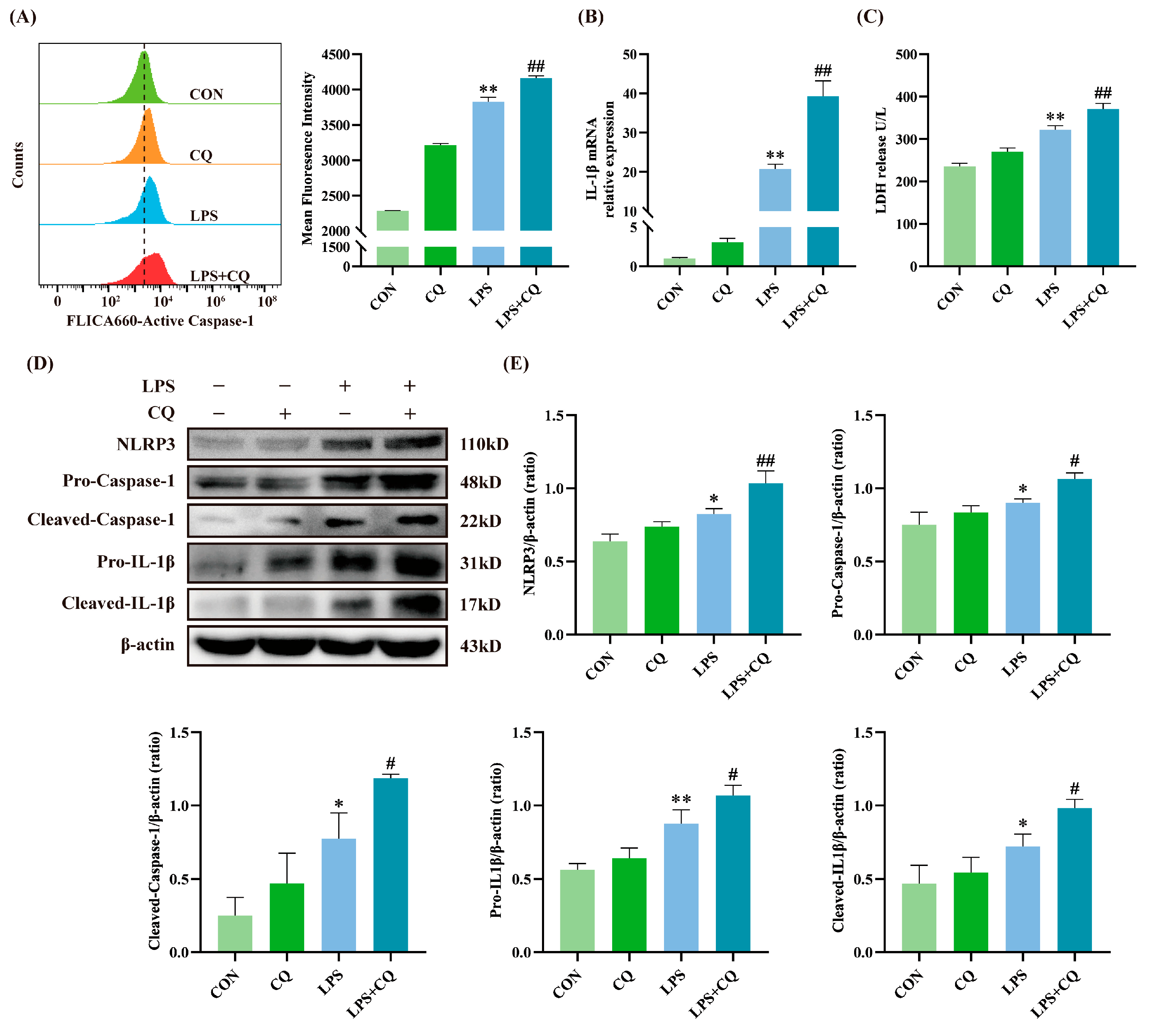

3.2. Inhibition of Autophagy Enhanced LPS-Induced Activation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome

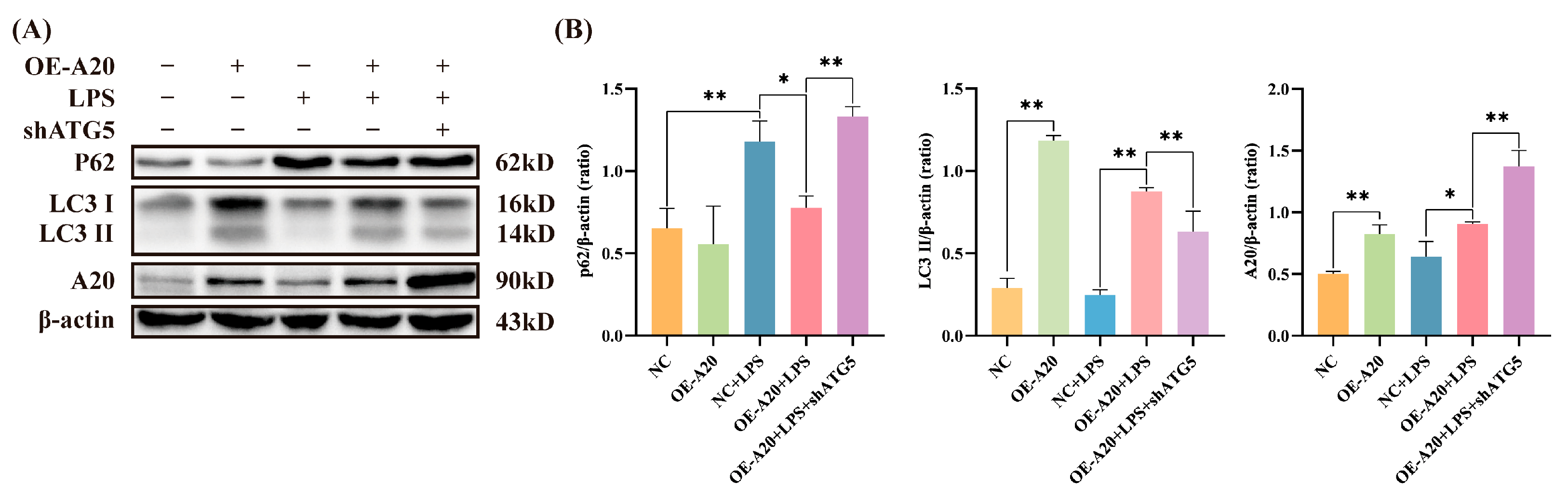

3.3. A20 Promoted Autophagy in BEECs

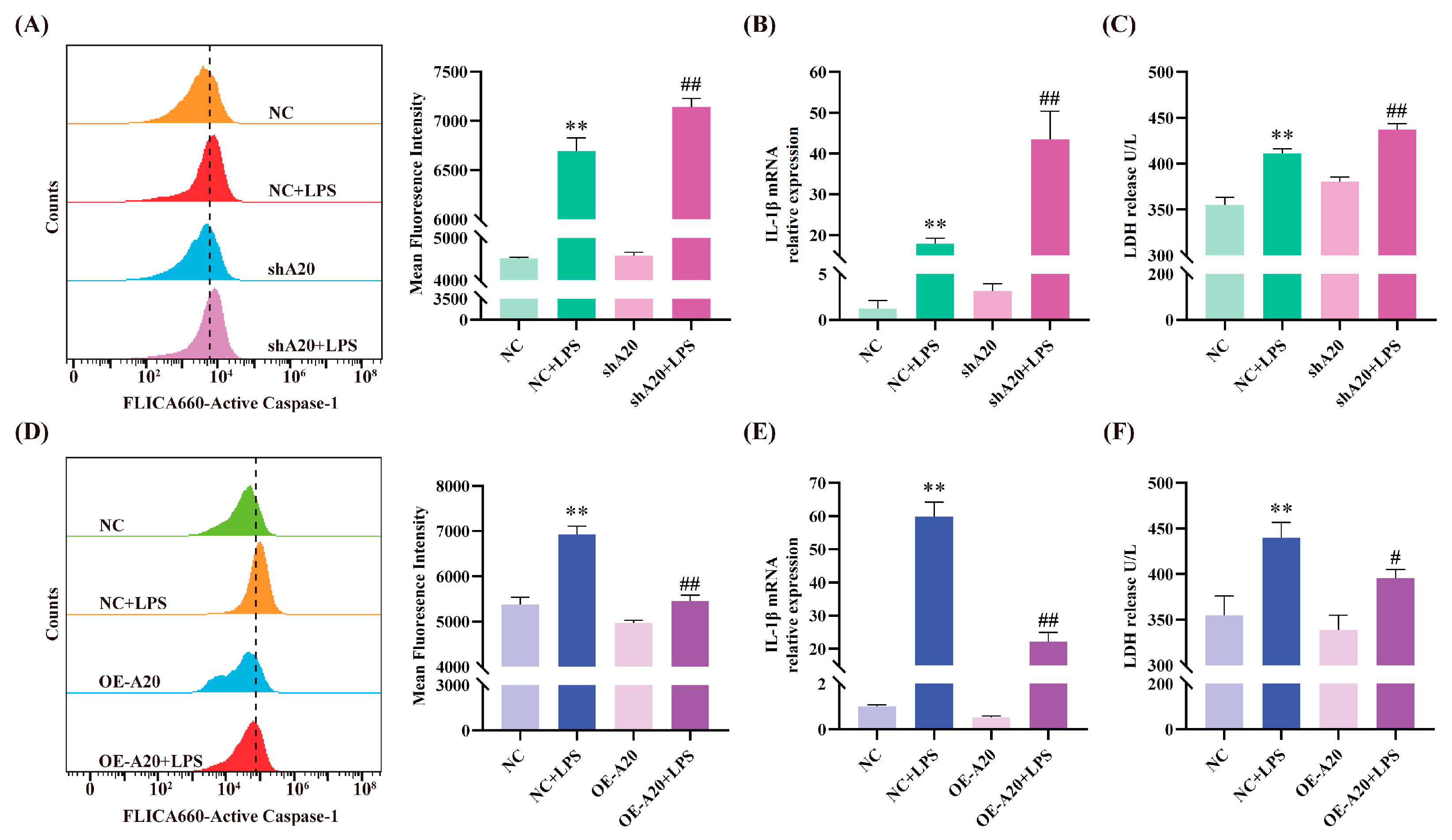

3.4. A20 Alleviates LPS-Induced Inflammatory Injury

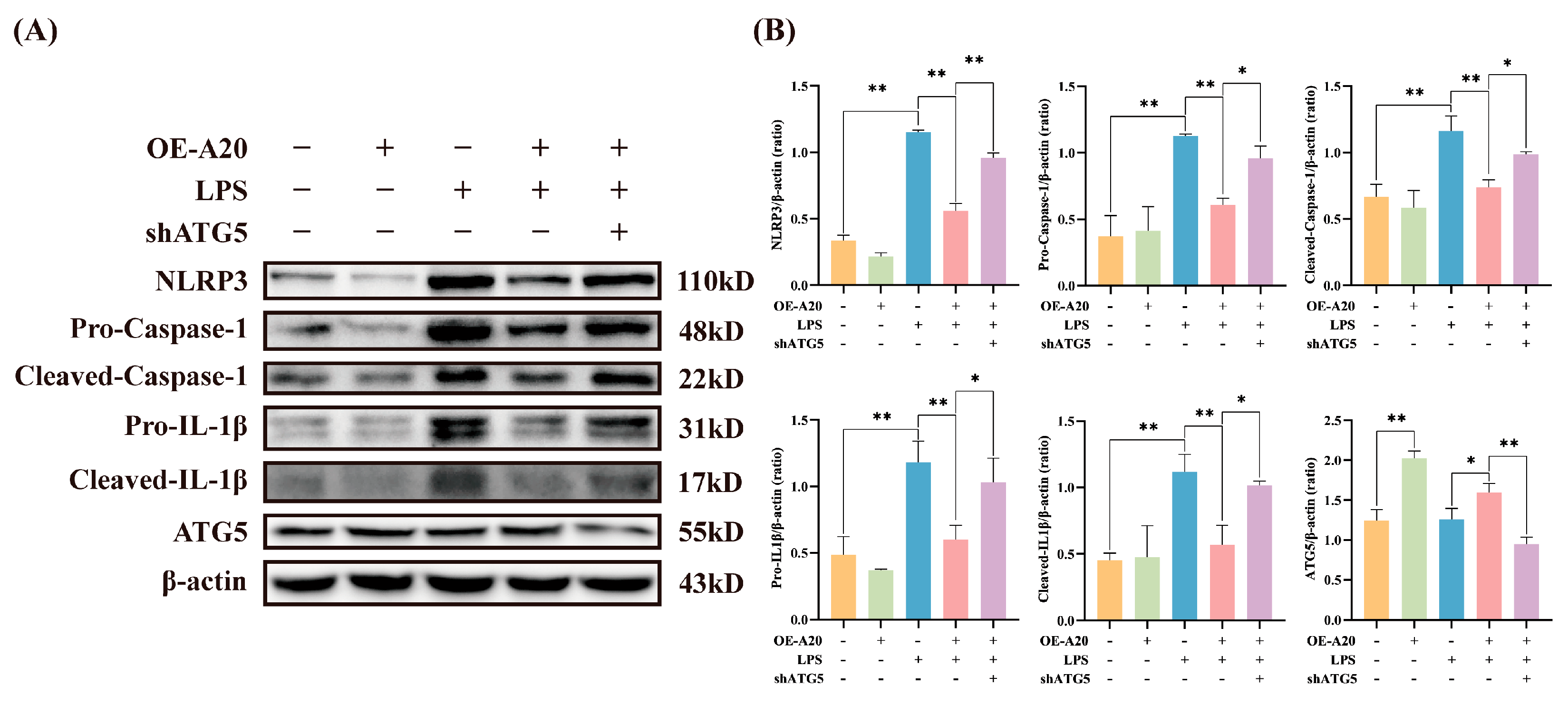

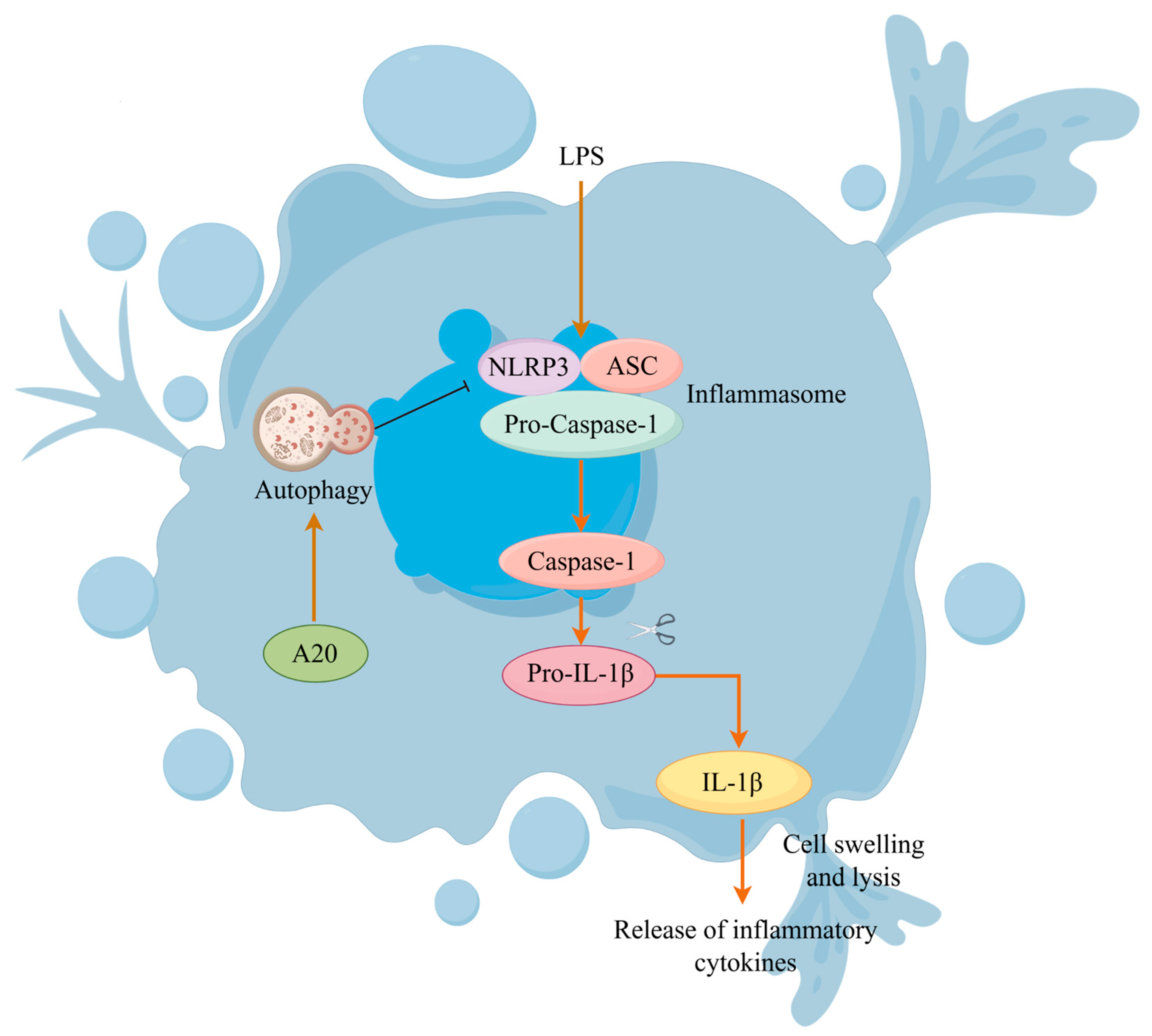

3.5. A20 Reduced NLRP3 Inflammasome Activity via Autophagy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sheldon, I.M.; Price, S.B.; Cronin, J.; Gilbert, R.O.; Gadsby, J.E. Mechanisms of infertility associated with clinical and subclinical endometritis in high producing dairy cattle. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2009, 44, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshghi, D.; Kafi, M.; Sharifiyazdi, H.; Azari, M.; Ahmadi, N.; Ghasrodashti, A.R.; Sadeghi, M. Intrauterine infusion of blood serum of dromedary camel improves the uterine health and fertility in high producing dairy cows with subclinical endometritis. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 240, 106973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, I.M. Diagnosing postpartum endometritis in dairy cattle. Vet. Rec. 2020, 186, 88–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahid, A.; Eiza, N.U.; Khalid, M.; Irshad, H.U.; Shabbir, M.A.B.; Ali, A.; Chaudhry, T.H.; Ahmed, S.; Maan, M.K.; Huang, L. Targeting inflammation for the treatment of endometritis in bovines. Microb. Pathog. 2024, 188, 106536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Zhang, C.; Bao, J.P.; Zhu, L.; Shi, R.; Xie, Z.Y.; Wang, F.; Wang, K.; Wu, X.T. A20 of nucleus pulposus cells plays a self-protection role via the nuclear factor-kappa B pathway in the inflammatory microenvironment. Bone Joint Res. 2020, 9, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slowicka, K.; Serramito-Gómez, I.; Boada-Romero, E.; Martens, A.; Sze, M.; Petta, I.; Vikkula, H.K.; De Rycke, R.; Parthoens, E.; Lippens, S.; et al. Physical and functional interaction between A20 and ATG16L1-WD40 domain in the control of intestinal homeostasis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, A.; van Loo, G. A20 at the Crossroads of Cell Death, Inflammation, and Autoimmunity. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2020, 12, a036418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Wang, L.; Shen, L.; Liu, W.; Li, Y.; Ma, H.; Wu, X. A20 ameliorates Aspergillus fumigatus keratitis by promoting autophagy and inhibiting NF-κB signaling. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Li, K.; Xue, R.; Liu, S.; Liu, X.; Wu, K. A20 functions as a negative regulator of the lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in corneal epithelial cells. Exp. Eye Res. 2023, 228, 109392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Mooney, E.C.; Xia, X.J.; Gupta, N.; Sahingur, S.E. A20 Restricts Inflammatory Response and Desensitizes Gingival Keratinocytes to Apoptosis. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biasizzo, M.; Kopitar-Jerala, N. Interplay Between NLRP3 Inflammasome and Autophagy. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 591803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandanmagsar, B.; Youm, Y.H.; Ravussin, A.; Galgani, J.E.; Stadler, K.; Mynatt, R.L.; Ravussin, E.; Stephens, J.M.; Dixit, V.D. The NLRP3 inflammasome instigates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, Q.; Zhao, X.; Tang, H.; Li, X.; Xiao, Y.; Wu, H.; Wu, Z.; Quan, J.; Chen, W. USP22 suppresses the NLRP3 inflammasome by degrading NLRP3 via ATG5-dependent autophagy. Autophagy 2023, 19, 873–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zeng, S.; Wang, P.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, C. NLRP3: A Promising Therapeutic Target for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Curr. Drug Targets 2023, 24, 1106–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deuteraiou, K.; Kitas, G.; Garyfallos, A.; Dimitroulas, T. Novel insights into the role of inflammasomes in autoimmune and metabolic rheumatic diseases. Rheumatol. Int. 2018, 38, 1345–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Ma, W.; Gao, W.; Xing, Y.; Chen, L.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Dai, Z. Propofol directly induces caspase-1-dependent macrophage pyroptosis through the NLRP3-ASC inflammasome. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Fu, X.; Wang, Q.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Wu, D. The Complex Interplay between Autophagy and NLRP3 Inflammasome in Renal Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Ji, B.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, K.; Guo, L.; Cui, L.; Wang, H.; Li, B.; Li, J. Autophagy activation alleviates the LPS-induced inflammatory response in endometrial epithelial cells in dairy cows. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2024, 91, e13820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, C.S.; Shenderov, K.; Huang, N.N.; Kabat, J.; Abu-Asab, M.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; Sher, A.; Kehrl, J.H. Activation of autophagy by inflammatory signals limits IL-1β production by targeting ubiquitinated inflammasomes for destruction. Nat. Immunol. 2012, 13, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegdekar, N.; Sarkar, C.; Bustos, S.; Ritzel, R.M.; Hanscom, M.; Ravishankar, P.; Philkana, D.; Wu, J.; Loane, D.J.; Lipinski, M.M. Inhibition of autophagy in microglia and macrophages exacerbates innate immune responses and worsens brain injury outcomes. Autophagy 2023, 19, 2026–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, Z.M.; Wang, K.; Gao, J.W.; Qian, Z.Y.; Bao, J.P.; Ji, H.Y.; Cabral, V.L.F.; Wu, X.T. A20 attenuates pyroptosis and apoptosis in nucleus pulposus cells via promoting mitophagy and stabilizing mitochondrial dynamics. Inflamm. Res. 2022, 71, 695–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Ji, B.; Jiang, Y.; Fei, F.; Guo, L.; Liu, K.; Cui, L.; Meng, X.; Li, J.; Wang, H. A20 Alleviates the Inflammatory Response in Bovine Endometrial Epithelial Cells by Promoting Autophagy. Animals 2024, 14, 2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascottini, O.B.; LeBlanc, S.J. Modulation of immune function in the bovine uterus peripartum. Theriogenology 2020, 150, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Violi, F.; Cammisotto, V.; Bartimoccia, S.; Pignatelli, P.; Carnevale, R.; Nocella, C. Gut-derived low-grade endotoxaemia, atherothrombosis and cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2023, 20, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vong, C.T.; Tseng, H.H.L.; Yao, P.; Yu, H.; Wang, S.; Zhong, Z.; Wang, Y. Specific NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors: Promising therapeutic agents for inflammatory diseases. Drug Discov. Today 2021, 26, 1394–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, L.; Shi, X. NLRP3 inflammasome and its role in autoimmune diseases: A promising therapeutic target. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 175, 116679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, J.E.; Wu, A.; Zhou, H.; Pham, M.A.; Lin, S.; McNulty, R. Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome for inflammatory disease therapy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2025, 46, 503–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, L.; Zhang, D.; Geng, H.; Sun, F.; Lei, M. Salidroside protects endothelial cells against LPS-induced inflammatory injury by inhibiting NLRP3 and enhancing autophagy. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2021, 21, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Sun, J.; Yuan, Y.; Lin, S.; Lin, J.; Mei, X. Zinc Promotes Microglial Autophagy Through NLRP3 Inflammasome Inactivation via XIST/miR-374a-5p Axis in Spinal Cord Injury. Neurochem. Res. 2022, 47, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, D.; Vince, J.E. Pyroptosis versus necroptosis: Similarities, differences, and crosstalk. Cell Death Differ. 2019, 26, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yan, M.; Shan, W.; Zhang, T.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, R.; Fang, J.; Mao, H. Bisphenol A induces pyroptotic cell death via ROS/NLRP3/Caspase-1 pathway in osteocytes MLO-Y4. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022, 159, 112772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, W.; Chen, Y.; Hu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, T.; Zeng, Y.; Efferth, T. Paeoniflorin inhibited GSDMD to alleviate ANIT-induced cholestasis via pyroptosis signaling pathway. Phytomedicine 2024, 134, 156021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, Y.; Baek, A.; Kim, D.E. Autophagy down-regulates NLRP3-dependent inflammatory response of intestinal epithelial cells under nutrient deprivation. BMB Rep. 2021, 54, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Tao, W.; Liu, F.; Wu, X.; Bi, H.; Shu, J.; Wang, D.; Li, X. Lipopolysaccharide promotes NLRP3 inflammasome activation by inhibiting TFEB-mediated autophagy in NRK-52E cells. Mol. Immunol. 2023, 163, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Cassel, S.L.; Sutterwala, F.S.; Dagvadorj, J. Regulation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by autophagy and mitophagy. Immunol. Rev. 2025, 329, e13410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Into, T.; Inomata, M.; Takayama, E.; Takigawa, T. Autophagy in regulation of Toll-like receptor signaling. Cell Signal. 2012, 24, 1150–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, K.; Klionsky, D.J. Xenophagy: A battlefield between host and microbe, and a possible avenue for cancer treatment. Autophagy 2017, 13, 223–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deretic, V. Autophagy in inflammation, infection, and immunometabolism. Immunity 2021, 54, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saitoh, T.; Fujita, N.; Jang, M.H.; Uematsu, S.; Yang, B.G.; Satoh, T.; Omori, H.; Noda, T.; Yamamoto, N.; Komatsu, M.; et al. Loss of the autophagy protein Atg16L1 enhances endotoxin-induced IL-1beta production. Nature 2008, 456, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Xu, W.; Wang, J.; Yan, J.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ge, W.; Wu, J.; Du, P.; Chen, Y. Boosting mTOR-dependent autophagy via upstream TLR4-MyD88-MAPK signalling and downstream NF-κB pathway quenches intestinal inflammation and oxidative stress injury. EBioMedicine 2018, 35, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Sun, S.; Sun, Y.; Song, Q.; Zhu, J.; Song, N.; Chen, M.; Sun, T.; Xia, M.; Ding, J.; et al. Small molecule-driven NLRP3 inflammation inhibition via interplay between ubiquitination and autophagy: Implications for Parkinson disease. Autophagy 2019, 15, 1860–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yi, W.; Xia, H.; Lan, H.; Chen, J.; Yang, Z.; Han, F.; Tang, P.; Liu, B. A20 regulates inflammation through autophagy mediated by NF-κB pathway in human nucleus pulposus cells and ameliorates disc degeneration in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 549, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Li, H.; Wu, Y.; Luo, M.; Chen, S.; Shen, G.; Wei, X.; Shao, B. Inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by A20 through modulation of NEK7. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2316551121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Shi, X.; Qian, T.; Li, J.; Tian, Z.; Ni, B.; Hao, F. A20 overexpression alleviates pristine-induced lupus nephritis by inhibiting the NF-κB and NLRP3 inflammasome activation in macrophages of mice. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 17430–17440. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.; Ye, Y.; Li, L.; Zhou, Y.; Hou, L.; Ren, S.; Xu, Y. A20 alleviated caspase-1-mediated pyroptosis and inflammation stimulated by Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide and nicotine through autophagy enhancement. Hum. Cell. 2022, 35, 803–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Y.; Lin, P.; Feng, Z.; Lu, H.; Han, Q.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.; He, Q.; Nan, G.; Luo, X.; et al. TNFAIP3-DEPTOR complex regulates inflammasome secretion through autophagy in ankylosing spondylitis monocytes. Autophagy 2018, 14, 1629–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Primers (5′→3′) | Product Size (bp) | Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-actin | F: CATCACCATCGGCAATGAGC R: AGCACCGTGTTGGCGTAGAG | 156 | NM_173979.3 |

| IL-1β | F: TGATGACCCTAAACAGATGAAGAGC R: CCACGATGACCGACACCACCT | 134 | NM_174093.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, Y.; Fei, F.; Wang, X.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, K.; Guo, L.; Cui, L.; Wang, H.; Dong, J.; Li, J. A20 Attenuates Inflammatory Injury in Bovine Endometrial Epithelial Cells Through Autophagy-Mediated NLRP3 Inflammasome Inactivation. Animals 2025, 15, 3513. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243513

Jiang Y, Fei F, Wang X, Jiang Y, Liu K, Guo L, Cui L, Wang H, Dong J, Li J. A20 Attenuates Inflammatory Injury in Bovine Endometrial Epithelial Cells Through Autophagy-Mediated NLRP3 Inflammasome Inactivation. Animals. 2025; 15(24):3513. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243513

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Yongshuai, Fan Fei, Xiaoyu Wang, Yeqi Jiang, Kangjun Liu, Long Guo, Luying Cui, Heng Wang, Junsheng Dong, and Jianji Li. 2025. "A20 Attenuates Inflammatory Injury in Bovine Endometrial Epithelial Cells Through Autophagy-Mediated NLRP3 Inflammasome Inactivation" Animals 15, no. 24: 3513. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243513

APA StyleJiang, Y., Fei, F., Wang, X., Jiang, Y., Liu, K., Guo, L., Cui, L., Wang, H., Dong, J., & Li, J. (2025). A20 Attenuates Inflammatory Injury in Bovine Endometrial Epithelial Cells Through Autophagy-Mediated NLRP3 Inflammasome Inactivation. Animals, 15(24), 3513. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15243513