A Portable Fluorometer Detects Significantly Elevated Cell-Free DNA in Tracheal Wash and Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid in Horses with Severe Asthma

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Horses

2.2. Clinical Scoring

2.3. Tracheal Wash Sample Collection and Processing

2.4. BALF Collection and Sample Processing

2.5. Cell-Free DNA Quantification

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Qubit 4 Fluorometer Correlation

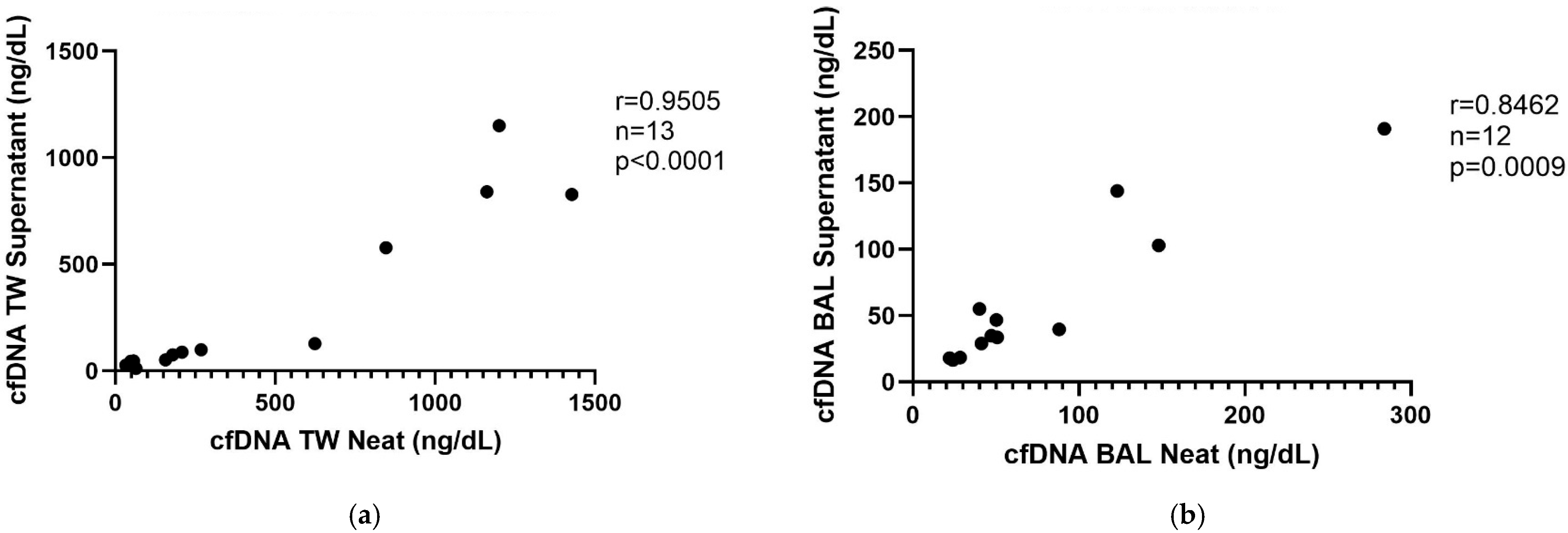

3.2. cfDNA Measurement in Unfiltered vs. Supernatant

3.3. Frozen/Thawed Supernatant

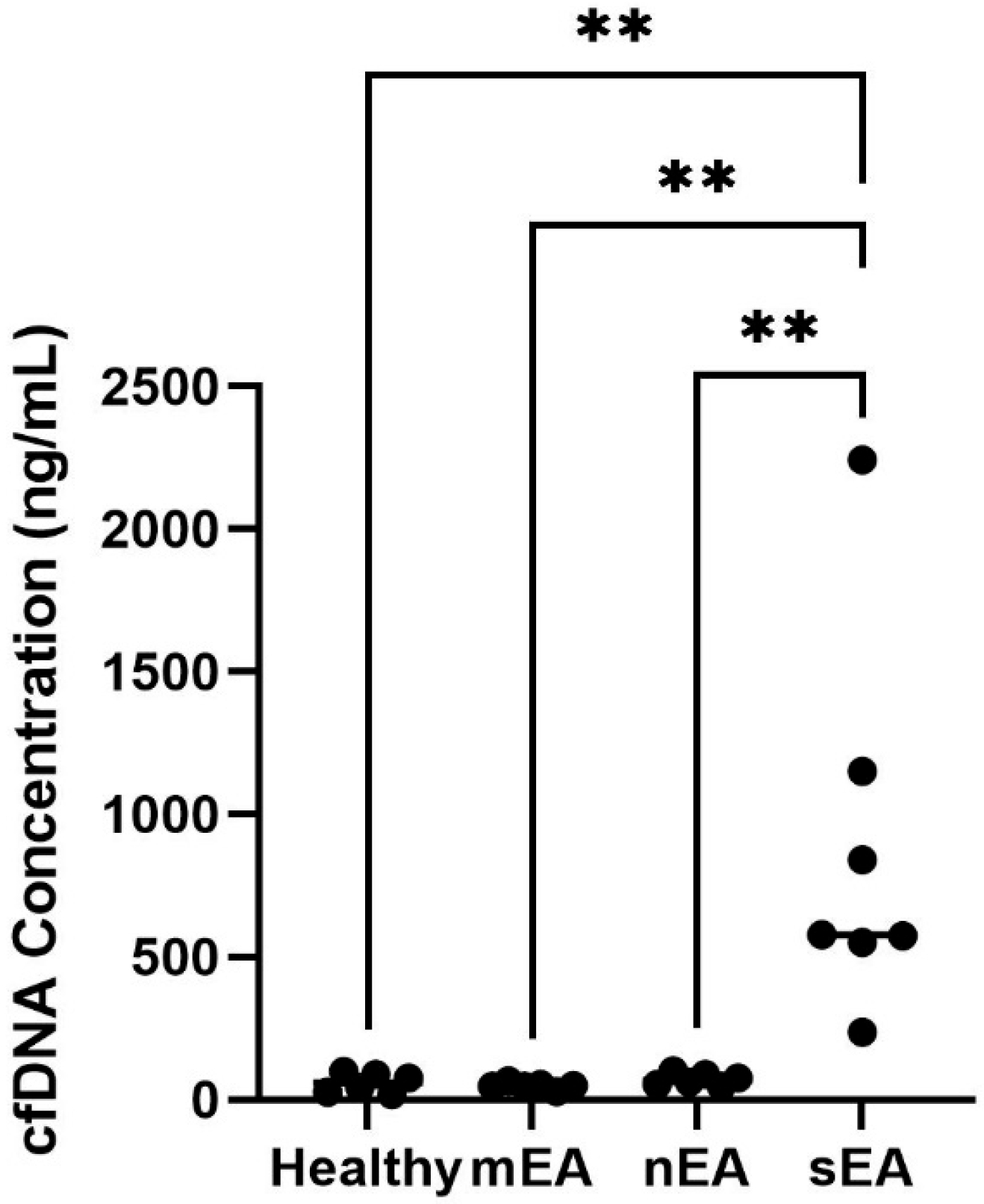

3.4. TW vs. BALF cfDNA

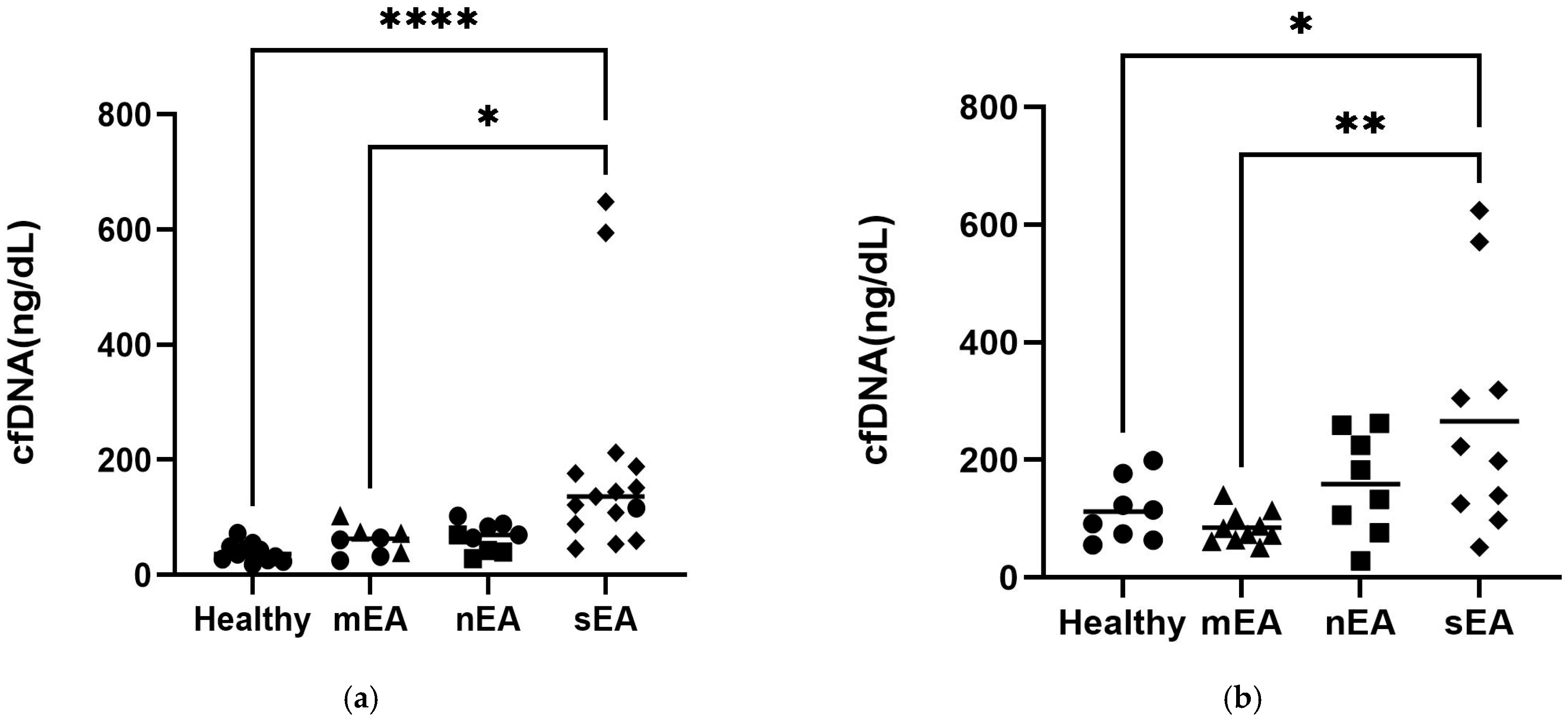

3.5. cfDNA Quantification

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| sEA | severe equine asthma |

| mEA | mild/moderate equine asthma |

| BALF | bronchoalveolar lavage fluid |

| TW | tracheal wash |

| NETs | neutrophil extracellular traps |

| cfDNA | cell-free DNA |

References

- Ivester, K.M.; Couëtil, L.L.; Zimmerman, N.J. Investigating the Link between Particulate Exposure and Airway Inflammation in the Horse. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2014, 28, 1653–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couroucé-Malblanc, A.; Pronost, S.; Fortier, G.; Corde, R.; Rossignol, F. Physiological Measurements and Upper and Lower Respiratory Tract Evaluation in French Standardbred Trotters During a Standardised Exercise Test on the Treadmill. Equine Vet. J. 2002, 34 (Suppl. S34), 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheats, M.K.; Davis, K.U.; Poole, J.A. Comparative Review of Asthma in Farmers and Horses. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2019, 19, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirie, R.S. Recurrent Airway Obstruction: A Review. Equine Vet. J. 2014, 46, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclere, M.; Lavoie-Lamoureux, A.; Lavoie, J.P. Heaves, an Asthma-like Disease of Horses. Respirology 2011, 16, 1027–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, J.; Sales Luís, J.; Tilley, P. Contribution of Lung Function Tests to the Staging of Severe Equine Asthma Syndrome in the Field. Res. Vet. Sci. 2019, 123, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigue Áre, S.; Viel, L.; Lee, E.; Mackay, R.J.; Hernandez, J.; Franchini, M. Cytokine Induction in Pulmonary Airways of Horses with Heaves and Effect of Therapy with Inhaled fluticasone Propionate. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2002, 85, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, D.M.; Grünig, G.; Matychak, M.B.; Young, J.; Wagner, B.; Erb, H.N.; Antczak, D.F. Recurrent Airway Obstruction (RAO) in Horses Is Characterized by IFN-γ and IL-8 Production in Bronchoalveolar Lavage Cells. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2003, 96, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullone, M.; Joubert, P.; Gagné, A.; Lavoie, J.P.; Hélie, P. Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid Neutrophilia Is Associated with the Severity of Pulmonary Lesions During Equine Asthma Exacerbations. Equine Vet. J. 2018, 50, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uberti, B.; Morán, G. Role of Neutrophils in Equine Asthma. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2018, 19, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, H.; Havervall, S.; Rosell, A.; Aguilera, K.; Parv, K.; Von Meijenfeldt, F.A.; Lisman, T.; MacKman, N.; Thålin, C.; Phillipson, M. Circulating Markers of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Are of Prognostic Value in Patients With COVID-19. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 988–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponti, G.; Maccaferri, M.; Micali, S.; Manfredini, M.; Milandri, R.; Bianchi, G.; Pellacani, G.; Kaleci, S.; Chester, J.; Conti, A.; et al. Seminal Cell Free DNA Concentration Levels Discriminate Between Prostate Cancer and Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Anticancer Res. 2018, 38, 5121–5125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letendre, J.A.; Goggs, R. Determining Prognosis in Canine Sepsis by Bedside Measurement of Cell-Free DNA and Nucleosomes. J. Vet. Emerg. Crit. Care 2018, 28, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couëtil, L.L.; Cardwell, J.M.; Gerber, V.; Lavoie, J.P.; Léguillette, R.; Richard, E.A. Inflammatory Airway Disease of Horses-Revised Consensus Statement. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2016, 30, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoensappakit, A.; Sae-khow, K.; Rattanaliam, P.; Vutthikraivit, N.; Pecheenbuvan, M.; Udomkarnjananun, S.; Leelahavanichkul, A. Cell-Free DNA as Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarkers for Adult Sepsis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware, S.A.; Kliment, C.R.; Giordano, L.; Redding, K.M.; Rumsey, W.L.; Bates, S.; Zhang, Y.; Sciurba, F.C.; Nouraie, S.M.; Kaufman, B.A. Cell-Free DNA Levels Associate with COPD Exacerbations and Mortality. Respir. Res. 2024, 25, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, J.E.; Dracopoli, N.C.; Bach, P.B.; Lau, A.; Scharpf, R.B.; Meijer, G.A.; Andersen, C.L.; Velculescu, V.E. Cell-Free DNA Approaches for Cancer Early Detection and Interception. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e006013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fingerhut, L.; Ohnesorge, B.; von Borstel, M.; Schumski, A.; Strutzberg-Minder, K.; Mörgelin, M.; Deeg, C.A.; Haagsman, H.P.; Beineke, A.; von Köckritz-Blickwede, M.; et al. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in the Pathogenesis of Equine Recurrent Uveitis (ERU). Cells 2019, 8, 1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayless, R.L.; Cooper, B.L.; Sheats, M.K. Extracted Plasma Cell-Free DNA Concentrations Are Elevated in Colic Patients with Systemic Inflammation. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayless, R.L.; Cooper, B.L.; Sheats, M.K. Investigation of Plasma Cell-Free DNA as a Potential Biomarker in Horses. J. Vet. Diagn. Investig. 2022, 34, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frippiat, T.; Art, T.; Tosi, I. Airway Hyperresponsiveness, but Not Bronchoalveolar Inflammatory Cytokines Profiles, Is Modified at the Subclinical Onset of Severe Equine Asthma. Animals 2023, 13, 2485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, H.; Virtala, A.M.; Raekallio, M.; Rahkonen, E.; Rajamäki, M.M.; Mykkänen, A. Comparison of Tracheal Wash and Bronchoalveolar Lavage Cytology in 154 Horses with and without Respiratory Signs in a Referral Hospital over 2009–2015. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tullie, S.; Asiri, A.; Acharjee, A.; Moiemen, N.S.; Lord, J.M.; Harrison, P.; Hazeldine, J. Day One Cell-Free DNA Levels as an Objective Prognostic Marker of Mortality in Major Burns Patients. Cells 2025, 14, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampson, P.; Dinsdale, R.J.; Wearn, C.M.; Bamford, A.L.; Bishop, J.R.; Hazeldine, J.; Moiemen, N.S.; Harrison, P.; Lord, J.M. Neutrophil Dysfunction, Immature Granulocytes, and Cell-free DNA are Early Biomarkers of Sepsis in Burn-injured Patients: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study. Ann. Surg. 2017, 265, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, P.; Tosi, I.; Hego, A.; Maréchal, P.; Marichal, T.; Radermecker, C. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps Are Found in Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluids of Horses with Severe Asthma and Correlate with Asthma Severity. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 921077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuberger, E.W.I.; Brahmer, A.; Ehlert, T.; Kluge, K.; Philippi, K.F.A.; Boedecker, S.C.; Weinmann-Menke, J.; Simon, P. Validating Quantitative PCR Assays for CfDNA Detection Without DNA Extraction in Exercising SLE Patients. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Chen, C.; Tu, Z.; Guo, Z.; Lu, T.; Li, J.; Wen, Y.; Chen, D.; Lei, W.; Wen, W.; et al. Intranasal PAMAM-G3 Scavenges Cell-Free DNA Attenuating the Allergic Airway Inflammation. Cell Death Discov. 2024, 10, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Chen, H.; Long, Y.; Li, P.; Gu, Y. The Main Sources of Circulating Cell-Free DNA: Apoptosis, Necrosis and Active Secretion. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2021, 157, 103166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papayannopoulos, V. Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Immunity and Disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018, 18, 134–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cooper, B.L.; Hobbs, K.J.; Bayless, R.; Stinson-Miller, A.; Gruber, E.; Hepworth-Warren, K.; Lavoie, J.-P.; Sheats, M.K. A Portable Fluorometer Detects Significantly Elevated Cell-Free DNA in Tracheal Wash and Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid in Horses with Severe Asthma. Animals 2025, 15, 3483. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233483

Cooper BL, Hobbs KJ, Bayless R, Stinson-Miller A, Gruber E, Hepworth-Warren K, Lavoie J-P, Sheats MK. A Portable Fluorometer Detects Significantly Elevated Cell-Free DNA in Tracheal Wash and Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid in Horses with Severe Asthma. Animals. 2025; 15(23):3483. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233483

Chicago/Turabian StyleCooper, Bethanie L., Kallie J. Hobbs, Rosemary Bayless, Austen Stinson-Miller, Erika Gruber, Kate Hepworth-Warren, Jean-Pierre Lavoie, and M. Katie Sheats. 2025. "A Portable Fluorometer Detects Significantly Elevated Cell-Free DNA in Tracheal Wash and Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid in Horses with Severe Asthma" Animals 15, no. 23: 3483. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233483

APA StyleCooper, B. L., Hobbs, K. J., Bayless, R., Stinson-Miller, A., Gruber, E., Hepworth-Warren, K., Lavoie, J.-P., & Sheats, M. K. (2025). A Portable Fluorometer Detects Significantly Elevated Cell-Free DNA in Tracheal Wash and Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid in Horses with Severe Asthma. Animals, 15(23), 3483. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233483