Subchondral and Osteochondral Unit Bone Damage in the Fetlock Region of Sport Horses Using Low-Field MRI: Case Series

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria and Study Design

2.2. Data Recorded

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Horses

3.2. Clinical History

3.3. Radiographic Findings

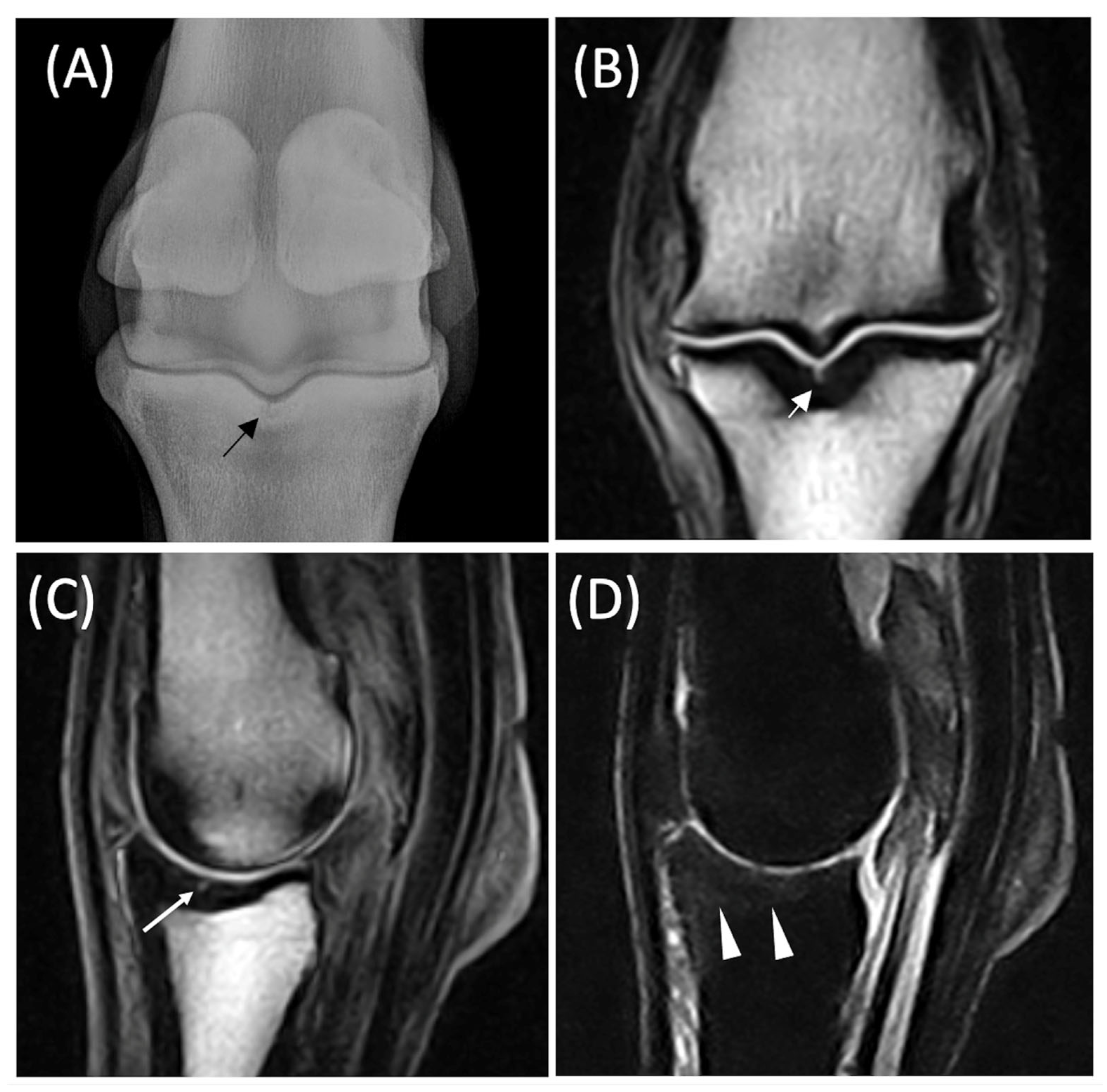

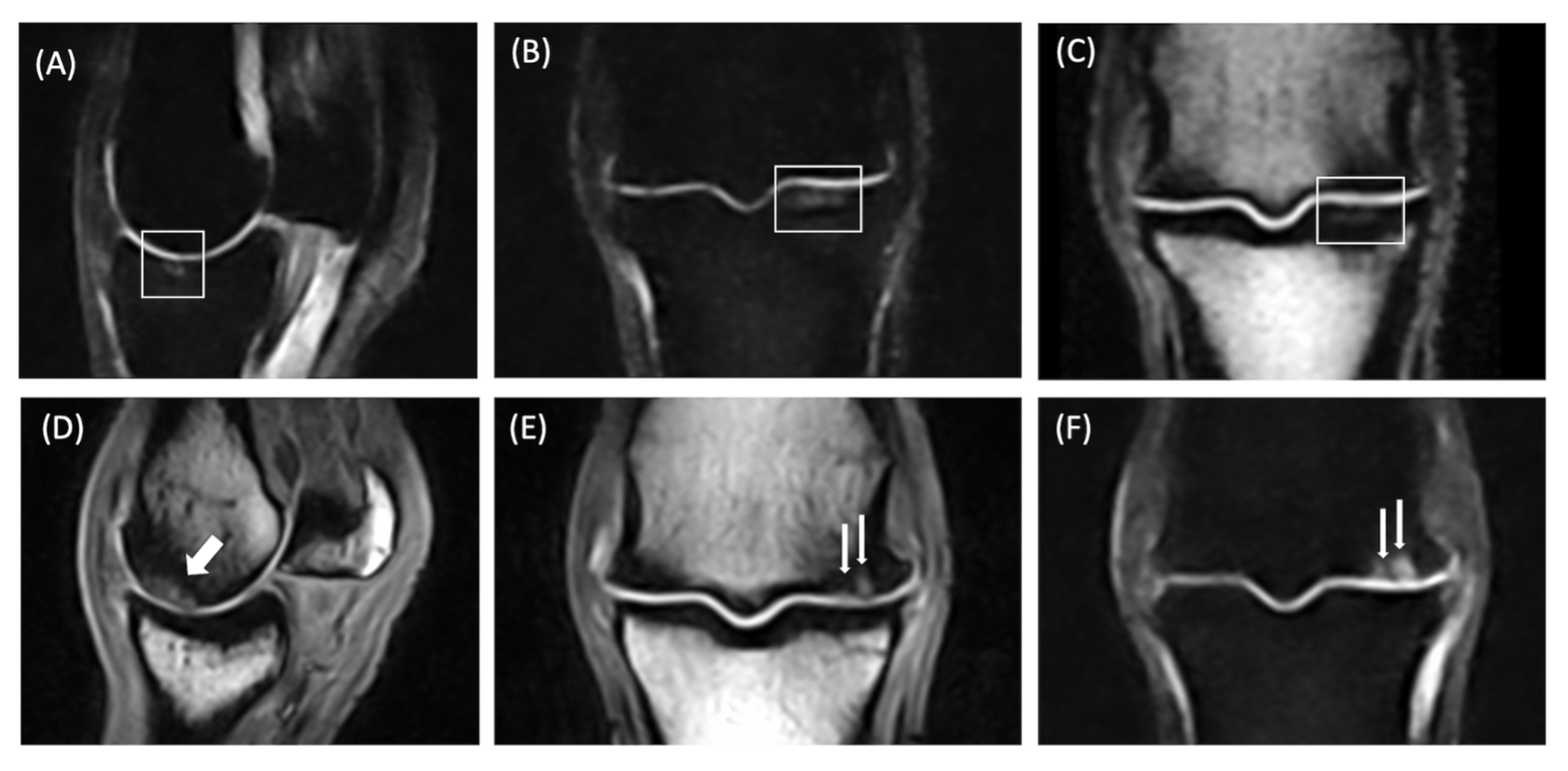

3.4. MRI Findings

3.5. Treatment

3.6. Outcome

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CB | cone-beam |

| CT | computed tomography |

| D-C-P | dorsal, central, palmar/plantar |

| BML | Bone Marrow Lesion |

| FB | fan-beam |

| IRU | increased radiopharmaceutical uptake |

| L-S-M | lateral, sagittal, medial |

| MCIII | Third Metacarpal Bone |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MTIII | Third Metatarsal Bone |

| POD | palmar osteochondral disease |

| PP | Proximal Phalanx |

| STIR | short tau inversion recovery |

| T1w | T1-weighted |

| T2w | T2-weighted |

References

- Powell, S.E. Low-field standing magnetic resonance imaging findings of the metacarpo/metatarsophalangeal joint of racing Thoroughbreds with lameness localised to the region: A retrospective study of 131 horses. Equine Vet. J. 2012, 44, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitton, R.C.; Ayodele, B.A.; Hitchens, P.L.; Mackie, E.J. Subchondral bone microdamage accumulation in distal metacarpus of Thoroughbred racehorses. Equine Vet. J. 2018, 50, 766–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bani Hassan, E.; Mirams, M.; Ghasem-Zadeh, A.; Mackie, E.J.; Whitton, R.C. Role of subchondral bone remodelling in collapse of the articular surface of Thoroughbred racehorses with palmar osteochondral disease. Equine Vet. J. 2016, 48, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olive, J.; Mair, T.S.; Charles, B. Use of standing low field magnetic resonance imaging to diagnose middle phalanx bone marrow lesions in horses. Equine Vet. Educ. 2009, 21, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olive, J.; D’anjou, M.; Alexander, K.; Laverty, S.; Theoret, C. Comparison of magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography and radiography for assessment of noncartilagineous changes in equine metacarpophalangeal osteoarthritis. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2010, 51, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, T.; Baker, T.A.; Brounts, S.H.; Sample, S.J.; Markel, M.D.; Scollay, M.C.; Marquis, P.; Muir, P. Detection of articular pathology of the distal aspect of the third metacarpal bone in thoroughbred racehorses: Comparison of radiography, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Vet. Surg. 2011, 40, 942–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, S.J.; Nagy, A.; Murray, R. Clinical and diagnostic imaging findings in horses with subchondral bone trauma of the sagittal groove of the proximal phalanx. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2011, 6, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, S.J.; Werpy, N.M.; Gutierrez-Nibeyro, S.D. Injuries of the sagittal groove of the proximal phalanx in warmblood horses detected with low-field magnetic resonance imaging: 19 cases (2007–2016). Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2017, 58, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.M.; Popp, K.L.; Yanovich, R.; Bouxsein, M.L.; Matheny, R.W., Jr. The role of adaptive bone formation in the etiology of stress fracture. Exp. Biol. Med. 2017, 242, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipreri, G.; Bladon, B.M.; Giorio, M.M.; Singer, E.R. Conservative versus surgical treatment of 21 sports horses with osseous trauma in the proximal phalangeal sagittal groove diagnosed by low-field MRI. Vet. Surg. 2018, 47, 908–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, E.D.; Pinchbeck, G.L.; Clegg, P.D.; Boyde, A.; Riggs, C.M. Post mortem evaluation of palmar osteochondral disease (traumatic osteochondrosis) of the metacarpo/metatarsophalangeal joint in Thoroughbred racehorses. Equine Vet. J. 2009, 41, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, P.; Peterson, A.L.; Sample, S.J.; Scollay, M.C.; Markel, M.D.; Kalscheur, V.L. Exercise-induced metacarpophalangeal joint adaptation in the Thoroughbred racehorse. J. Anat. 2008, 213, 706–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madry, H.; van Dijk, C.N.; Mueller-Gerbl, M. The basic science of the subchondral bone. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2010, 18, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepage, S.I.M.; Robson, N.; Gilmore, H.; Davis, O.; Hooper, A.; St John, S.; Kamesan, V.; Gelis, P.; Carvajal, D.; Hurtig, M.; et al. Beyond Cartilage Repair: The Role of the Osteochondral Unit in Joint Health and Disease. Tissue Eng. Part. B Rev. 2019, 25, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherlock, C.E.; Mair, T.S.; Ter Braake, F. Ossesous lesions in the metacarpo(tarso)phalangeal joint diagnosed using low-field magnetic resonance imaging in standing horse. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2009, 50, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramzan, P.H.L.; Powell, S.E. Clinical and imaging features of suspected prodromal fracture of the proximal phalanx in three Thoroughbred racehorses. Equine Vet. J. 2010, 42, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranquille, C.A.; Parkin, T.D.H.; Murray, R.C. Magnetic resonance imaging-detected adaptation and pathology in the distal condyles of the third metacarpus, associated with lateral condylar fracture in Thoroughbred racehorses. Equine Vet. J. 2012, 44, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesca, H.; Fairburn, A.; Sherlock, C.; Mair, T. The use of advanced vs. conventional imaging modalities for the diagnosis of subchondral bone injuries. Equine Vet. Educ. 2022, 34, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubrod, C.J.; Schneider, R.K.; Tucker, R.L.; Gavin, P.R.; Ragle, C.A.; Farnsworth, K.D. Use of magnetic resonance imaging for identifying subchondral bone damage in horses: 11 cases (1999–2003). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2004, 224, 411–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.N.; Zubrod, C.J.; Schneider, R.K.; Sampson, S.N.; Roberts, G. MRI findings in 232 horses with lameness localized to the metacarpo(tarso)phalangeal region and without a radiographic diagnosis. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2013, 54, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-T.; Foote, A.K.; Bolas, N.M.; Peter, V.G.; Pokora, R.; Patrick, H.; Sargan, D.R.; Murray, R.C. Three-Dimensional Imaging and Histopathological Features of Third Metacarpal/Tarsal Parasagittal Groove and Proximal Phalanx Sagittal Groove Fissures in Thoroughbred Horses. Animals 2023, 13, 2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, B.B.; Kawcak, C.E.; Barrett, M.F.; McIlwraith, C.W.; Grinstaff, M.W.; Goodrich, L.R. Recent advances in articular cartilage evaluation using computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Equine Vet. J. 2018, 50, 564–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovel, T.; Audigié, F.; Coudry, V.; Jaquet-Guibon, S.; Bertoni, L.; Denoix, J.M. Evaluation of standing low-field magnetic resonance imaging for diagnosis of advanced distal interphalangeal primary degenerative joint disease in horses: 12 cases (2010–2014). J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2019, 254, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, R.C.; Branch, M.V.; Tranquille, C.; Woods, S. Validation of magnetic resonance imaging for measurement of equine articular cartilage and subchondral bone thickness. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2005, 66, 1999–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faulkner, J.E.; Joostens, Z.; Broeckx, B.J.G.; Hauspie, S.; Mariën, T.; Vanderperren, K. Follow-Up Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Sagittal Groove Disease of the Equine Proximal Phalanx Using a Classification System in 29 Non-Racing Sports Horses. Animals 2024, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AAEP Horse Show Committee. Guide to Veterinary Services for Horses Shows, 7th ed.; American Association of Equine Practitioners: Lexington, KY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Viana, S.L.; Machado, B.B.; Mendlovitz, P.S. MRI of subchondral fractures: A review. Skelet. Radiol. 2014, 43, 1515–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itha, R.; Vaishya, R.; Vaish, A.; Migliorini, F. Management of chondral and osteochondral lesions of the hip: A comprehensive review. Orthopadie 2024, 53, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, B.; Fritz, J. MR Imaging of Acute Knee Injuries: Systematic Evaluation and Reporting. Radiol. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 61, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohndorf, K. Imaging of acute injuries of the articular surfaces (chondral, osteochondral and subchondral fractures). Skelet. Radiol. 1999, 28, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigheb, M.; Guzzardi, G.; Barini, M.; Abruzzese, M.; Riva, S.; Paschè, A.; Pogliacomi, F.; Rimondini, L.; Stecco, A.; Grassi, F.A.; et al. Role of low-field MRI in detecting knee lesions. Acta Biomed. 2019, 90, 116–122. [Google Scholar]

- Werpy, N.M.; Ho, C.P.; Pease, A.P.; Kawcak, C.E. The effect of sequence selection and field strength on detection of osteochondral defects in the metacarpophalangeal joint. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2011, 52, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krakowski, P.; Karpinski, R.; Jojczuk, M.; Nogalska, A.; Jonak, J. Knee MRI underestimates the grade of cartilage lesions. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.A.; Dyson, S.J.; Murray, R.C. Reliability of high- and low-field magnetic resonance imaging system for detection of cartilage and bone lesions in the equine cadaver fetlock. Equine Vet. J. 2012, 44, 684–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, A.; Malton, R. Diffusion of radiodense contrast medium after perineural injection of the palmar digital nerves. Equine Vet. Educ. 2015, 27, 648–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.R.W.; Corletto, F.C.; Wright, I.M. Parasagittal fractures of the proximal phalanx in Thoroughbred racehorses in the UK: Outcome of repaired fractures in 113 cases (2007–2011). Equine Vet. J. 2017, 49, 784–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, D.R.; Simpson, D.J.; Greenwood, R.E.; Crowhurst, J.S. Observations and management of fractures of the proximal phalanx in young Tohroughbreds. Equine Vet. J. 1987, 19, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuemmerle, J.M.; Auer, J.A.; Rademacher, N.; Lischer, C.J.; Bettschart-Wolfensberger, R.; Furst, A.E. Short incomplete fractures of the proximal phalanx in ten horses not used for racing. Vet. Surg. 2008, 37, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, B.R.; Bergman, A.G.; Miner, M.; Arendt, E.A.; Klevansky, A.B.; Matheson, G.O.; Norling, T.L.; Marcus, R. Tibial stress injuries: Relationship of radiographic, nuclear medicine bone scanning, MR imaging, and CT severity grades to clinical severity and time to healing. Radiology 2012, 263, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathria, M.N.; Chung, C.B.; Resnick, D.L. Acute stress-related injuries of bone and cartilage: Pertinent anatomy, basic biomechanics, and imaging perspective. Radiology 2016, 280, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, J.; Pasquotti, G.; Smith, M.K.; Gupta, A.; Lesniak, B.P.; Kaplan, L.D. Subchondral insufficiency fractures of the knee: A review of imaging findings. Acta Radiol. 2015, 56, 714–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyid, S.; Younan, Y.; Sharma, G.; Singer, A.; Morrison, W.; Zoga, A.; Gonzalez, F.M. Subchondral insufficiency fracture of the knee: Grading, risk factors, and outcome. Skelet. Radiol. 2019, 48, 1961–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, H.; Deng, Z.; Liu, J.; Chen, S.; Deng, Z.; Li, W. The Mechanism of Bone Remodeling After Bone Aging. Clin. Interv. Aging 2022, 5, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, M.; Odgaard, A.; Linde, F.; Hvid, I. Age-related variations in the microstructure of human tibial cancellous bone. J. Orthop. Res. 2002, 20, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zheng, Q.; Landao-Bassonga, E.; Cheng, T.S.; Pavlos, N.J.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, M.H. Influence of age and gender on microarchitecture and bone remodeling in subchondral bone of the osteoarthritic femoral head. Bone 2015, 77, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martig, S.; Hitchens, P.L.; Stevenson, M.A.; Whitton, R.C. Subchondral bone morphology in the metacarpus of racehorses in training changes with distance from the articular surface but not with age. J. Anat. 2018, 232, 919–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler Ransohoff, C.; Matziolis, G.; Eijer, H. Calcium dobesilate (Doxium®) in bone marrow edema syndrome and suspected osteonecrosis of the hip joint—A case series. J. Orthop. 2020, 21, 449–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, J.E.; Wenck, A.; Fricker, C.; Svalastoga, E.L. Modulation of the intramedullary pressure responses by calcium dobesilate in a rabbit knee model of osteoarthritis. Acta Orthop. 2011, 82, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MRI Consistent Lesion Features | Additional Possible MRI Findings | |

|---|---|---|

| Subchondral lesion | Arcuated or linear or irregular localized hyperintensity within the subchondral bone in all sequences; the subchondral black line, due to chemical shift artifacts, is normal in shape, signal and thickness; no indentation/depression of the overlying cartilage | Perilesional or diffuse BML |

| Osteochondral Unit lesion | Arcuated or irregular localized hyperintensity in all sequences extended from the cartilage layer to the subchondral plate, with disruption of the black line; depression of the cartilage into bone can be observed, as well as a cartilage defect | Perilesional or diffuse BML; fissure |

| Fissure | Linear hyperintensity with proximodistal orientation extending from the cartilage layer to the subchondral or the trabecular bone; the black line is interrupted; depression of the cartilage into bone can be observed, as well as a cartilage defect | Perilesional bone densification and/or diffuse BML |

| BML | Ill-defined low signal intensity of the trabecular bone on T1w images and ill-defined areas of high signal intensity on T2w or STIR images | Subchondral or osteochondral lesions; fissure; bone densification |

| Bone sclerosis | Ill-defined low-signal intensity areas in all sequences directly in contact with the subchondral bone | BML; fissure; subchondral or osteochondral lesions |

| Localization on the transverse plane | ||

| Dorsal | Between the dorsal cortex of PP or MCIII/MTIII and the dorsal border of the collateral ligament fossae | |

| Palmar/Plantar | Between the palmar/plantar border of the collateral ligament fossae and the palmar/plantar cortex of PP or MCIII/MTIII | |

| Central | Between the dorsal and the palmar/plantar borders of the collateral ligament fossae | |

| Localization on the dorsal plane | ||

| Sagittal | Involvement of the sagittal ridge of MCIII/MTIII or of the sagittal groove of PP | |

| Medial | Involvement of the medial condyle of MCIII/MTIII or of the medial aspect of PP | |

| Lateral | Involvement of the lateral condyle of MCIII/MTIII or of the lateral aspect of PP | |

| Case | Fetlock | Onset | Lameness Duration | Lameness Grade | Localization | MRI Lesions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fissure | Subchondral Lesion | Osteochondral Unit Lesion | Outcome | ||||||

| 1 | LF | progressive | 2 weeks | 4 | medial articular surface PP | no | no | yes | negative |

| 2 | LH | acute | 4 weeks | 3 | medial articular surface PP | no | yes | yes | sound at work, same level |

| medial condyle, dorsal | no | yes | no | ||||||

| 3 | RH | acute | 4 weeks | 3 | sagittal groove PP, centro-plantar | yes | no | yes | negative |

| 4 | RH | acute | 8 weeks | 2 | sagittal groove PP, central | no | yes | no | sound at work, same level |

| 5 | LF | acute | 52 weeks | 2 | medial articular surface PP | no | yes | no | sound at work, same level |

| 6 | LH | progressive | 8 weeks | 2 | POD lateral | no | yes | no | sound at work, same level |

| POD medial | no | yes | no | ||||||

| 7 | LF | acute | 2 weeks | 3 | medial condyle, dorsal | no | no | yes | negative |

| 8 | LH | acute | 52 weeks | 1 | sagittal groove PP, central | yes | no | yes | negative |

| 9 | LF | acute | 26 weeks | 3 | medial condyle, dorsal | yes | no | yes | negative |

| 10 | RF | acute | 8 weeks | 2 | sagittal groove PP, centro-dorsal | no | no | yes | sound at work, same level |

| 11 | RF | acute | 2 weeks | 4 | sagittal groove PP, dorsal | yes | no | yes | sound at work, same level |

| 12 | LF | acute | 16 weeks | 2 | medial articular surface PP | no | no | yes | negative |

| 13 | RF | acute | 8 weeks | 4 | sagittal groove PP, central | no | no | yes | negative |

| 14 | RH | acute | 16 weeks | 2 | sagittal groove PP, central | yes | no | yes | sound at work, same level |

| 15 | RF | acute | 2 weeks | 2 | medial condyle, dorsal | yes | no | yes | negative, retired from work |

| 16 | LF | acute | 8 weeks | 3 | medial condyle, dorsal | no | no | yes | sound at work, same level |

| 17 | RF | acute | 4 weeks | 3 | sagittal groove PP, central | yes | no | yes | sound at work, low level |

| 18 | RF | acute | 4 weeks | 2 | medial condyle, dorsal | yes | no | yes | sound at work, same level |

| 19 | LF | acute | 8 weeks | 2 | medial condyle, dorsal | no | yes | no | sound at work, same level |

| 20 | RF | acute | 2 weeks | 2 | medial articular surface PP | no | yes | no | sound at work, same level |

| 21 | RF | acute | 8 weeks | 2 | medial condyle, dorsal | no | no | yes | negative, retired from work |

| 22 | RF | acute | 8 weeks | 3 | sagittal groove PP, central | no | yes | no | sound at work, same level |

| 23 | RF | acute | 8 weeks | 2 | sagittal groove PP, centro-dorsal | no | yes | no | sound at work, same level |

| 24 | RF | acute | 8 weeks | 1 | sagittal groove PP, central | yes | no | yes | sound at work, same level |

| 25 | LF | progressive | 2 weeks | 2 | medial articular surface PP | yes | yes | yes | sound at work, same level |

| medial condyle, dorsal | yes | no | yes | ||||||

| 26 | LF | progressive | 4 weeks | 2 | sagittal groove PP, central | yes | no | yes | negative, retired from work |

| 27 | LF | acute | 2 weeks | 2 | medial condyle, dorsal | yes | no | yes | sound at work, same level |

| 28 | RF | progressive | 12 weeks | 2 | medial condyle, centro-palmar | no | yes | no | sound at work, same level |

| 29 | LF | acute | 8 weeks | 1 | POD lateral | no | no | yes | negative, retired from work |

| POD medial | no | no | yes | ||||||

| 30 | LF | acute | 4 weeks | 2 | medial condyle, dorsal | no | no | yes | sound at work, same level |

| 31 | RF | acute | 4 weeks | 2 | POD lateral | no | yes | no | sound at work, same level |

| 32 | LF | acute | 4 weeks | 2 | medial articular surface PP | no | yes | no | sound at work, same level |

| 33 | RF | acute | 2 weeks | 4 | medial condyle, dorsal | no | no | yes | sound at work, same level |

| 34 | LF | acute | 4 weeks | 3 | medial condyle, dorsal | no | no | yes | negative, retired from work |

| 35 | LF | acute | 8 weeks | 2 | medial condyle, dorsal | no | no | yes | sound at work, low level |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

De Zani, D.; Rabbogliatti, V.; Rabba, S.; Auletta, L.; Longo, M.; Zani, D.D. Subchondral and Osteochondral Unit Bone Damage in the Fetlock Region of Sport Horses Using Low-Field MRI: Case Series. Animals 2025, 15, 3468. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233468

De Zani D, Rabbogliatti V, Rabba S, Auletta L, Longo M, Zani DD. Subchondral and Osteochondral Unit Bone Damage in the Fetlock Region of Sport Horses Using Low-Field MRI: Case Series. Animals. 2025; 15(23):3468. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233468

Chicago/Turabian StyleDe Zani, Donatella, Vanessa Rabbogliatti, Silvia Rabba, Luigi Auletta, Maurizio Longo, and Davide D. Zani. 2025. "Subchondral and Osteochondral Unit Bone Damage in the Fetlock Region of Sport Horses Using Low-Field MRI: Case Series" Animals 15, no. 23: 3468. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233468

APA StyleDe Zani, D., Rabbogliatti, V., Rabba, S., Auletta, L., Longo, M., & Zani, D. D. (2025). Subchondral and Osteochondral Unit Bone Damage in the Fetlock Region of Sport Horses Using Low-Field MRI: Case Series. Animals, 15(23), 3468. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233468