Associations Between REM Sleep-like Posture Expression and Cognitive Flexibility in 2-Month-Old Japanese Black Calves

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Housing and Animals

2.3. RSLP Observation

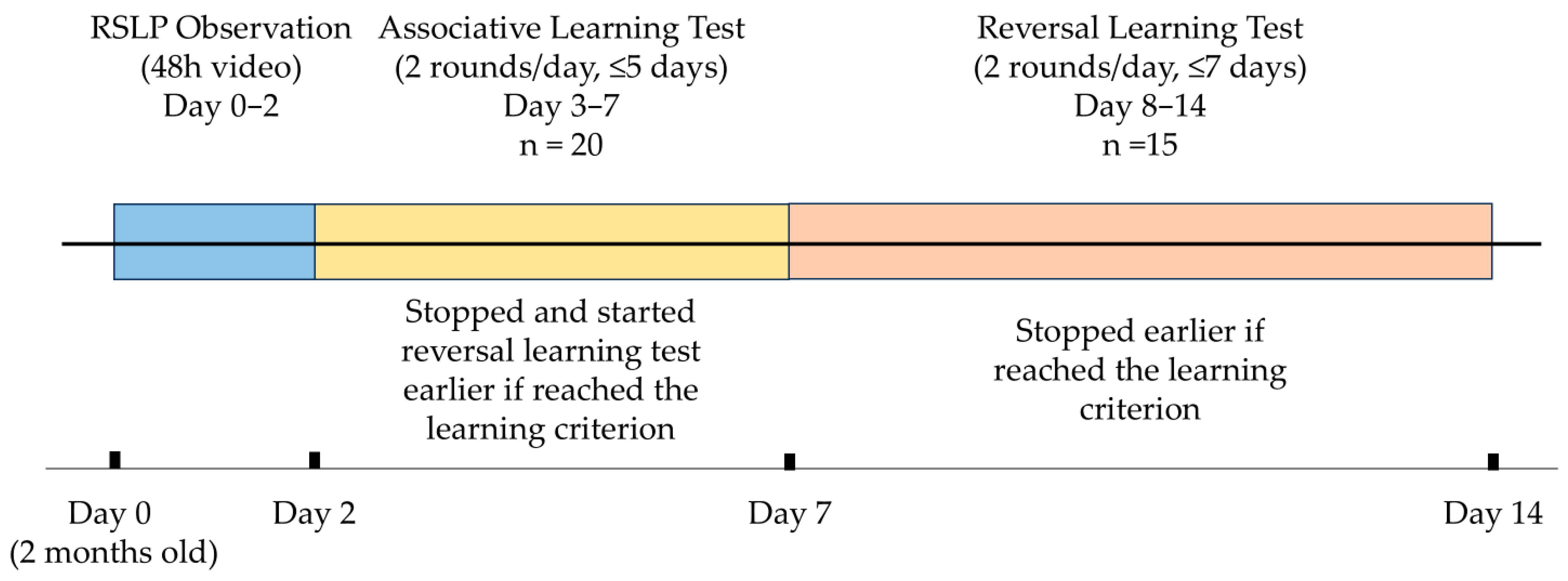

2.4. Associative Learning Test and Reversal Learning Test

2.4.1. Associative Learning Test

2.4.2. Reversal Learning Test

2.5. Statistical Analysis

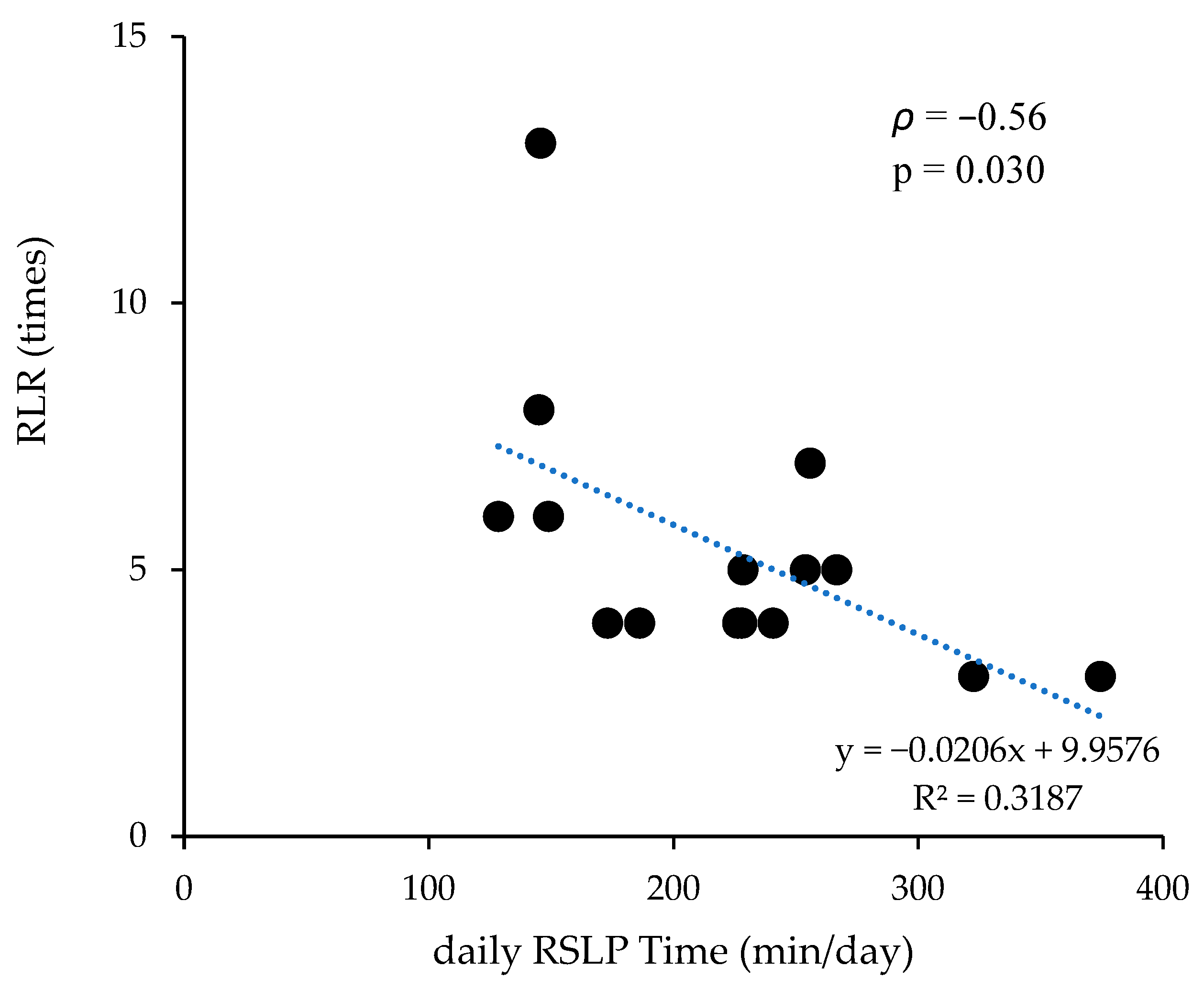

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miyazaki, S.; Liu, C.Y.; Hayashi, Y. Sleep in Vertebrate and Invertebrate Animals, and Insights into the Function and Evolution of Sleep. Neurosci. Res. 2017, 118, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukasawa, M. The Development of Sleep-like Posture Expression with Age in Female Holstein Calves. Anim. Sci. J. 2023, 94, e13816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, J.M. Clues to the Functions of Mammalian Sleep. Nature 2005, 437, 1264–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, J.G.; Strecker, R.E. The Cognitive Cost of Sleep Lost. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2011, 96, 564–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokhandwala, S.; Spencer, R.M.C. Relations between Sleep Patterns Early in Life and Brain Development: A Review. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2022, 56, 101130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänninen, L.; Mäkelä, J.P.; Rushen, J.; de Passillé, A.M.; Saloniemi, H. Assessing Sleep State in Calves through Electrophysiological and Behavioural Recordings: A Preliminary Study. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 111, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänninen, L.; Hepola, H.; Raussi, S.; Saloniemi, H. Effect of Colostrum Feeding Method and Presence of Dam on the Sleep, Rest and Sucking Behaviour of Newborn Calves. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 112, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mealey, L. Sleep (Zoology). Available online: https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/zoology/sleep-zoology (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Blumberg, M.S.; Dooley, J.C.; Tiriac, A. Sleep, Plasticity, and Sensory Neurodevelopment. Neuron 2022, 110, 3230–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruckebusch, Y. Feeding and Sleep Patterns of Cows Prior to and Post Parturition. Appl. Anim. Ethol. 1975, 1, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.B.; Jensen, M.B.; de Passillé, A.M.; Hänninen, L.; Rushen, J. Invited Review: Lying Time and the Welfare of Dairy Cows. J. Dairy. Sci. 2021, 104, 20–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rial, R.V.; Nicolau, M.C.; Gamundí, A.; Akaârir, M.; Aparicio, S.; Garau, C.; Tejada, S.; Roca, C.; Gené, L.; Moranta, D.; et al. The Trivial Function of Sleep. Sleep Med. Rev. 2007, 11, 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duclos, C.; Beauregard, M.P.; Bottari, C.; Ouellet, M.C.; Gosselin, N. The Impact of Poor Sleep on Cognition and Activities of Daily Living after Traumatic Brain Injury: A Review. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2015, 62, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, J.A.; Pace-Schott, E.F. The Cognitive Neuroscience of Sleep: Neuronal Systems, Consciousness and Learning. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002, 3, 679–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wechsler, B.; Lea, S.E.G. Adaptation by Learning: Its Significance for Farm Animal Husbandry. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2007, 108, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawroth, C.; Langbein, J.; Coulon, M.; Gabor, V.; Oesterwind, S.; Benz-Schwarzburg, J.; von Borell, E. Farm Animal Cognition-Linking Behavior, Welfare and Ethics. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brando, S.I.C.A. Animal Learning and Training. Implications for Animal Welfare. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Exot. Anim. Pract. 2012, 15, 387–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seganfreddo, S.; Fornasiero, D.; De Santis, M.; Mutinelli, F.; Normando, S.; Contalbrigo, L. A Pilot Study on Behavioural and Physiological Indicators of Emotions in Donkeys. Animals 2023, 13, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greening, L.; McBride, S. A Review of Equine Sleep: Implications for Equine Welfare. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 916737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieling, E.T.; Nordquist, R.E.; van der Staay, F.J. Assessing Learning and Memory in Pigs. Anim. Cogn. 2011, 14, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, S.; Nürnberg, G.; Puppe, B.; Langbein, J. The Cognitive Capabilities of Farm Animals: Categorisation Learning in Dwarf Goats (Capra hircus). Anim. Cogn. 2012, 15, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, P.I. Conditioned Reflexes: An Investigation of the Physiological Activity of the Cerebral Cortex. Ann. Neurosci. 2010, 17, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Henshall, J.M.; Wark, T.J.; Crossman, C.C.; Reed, M.T.; Brewer, H.G.; O’Grady, J.; Fisher, A.D. Associative Learning by Cattle to Enable Effective and Ethical Virtual Fences. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2009, 119, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonney-King, J.; Fischer, J.; Miller-Cushon, E. Effects of Reward Type and Previous Social Experience on Cognitive Testing Outcomes of Weaned Dairy Calves. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klefot, J.M.; Murphy, J.L.; Donohue, K.D.; O’Hara, B.F.; Lhamon, M.E.; Bewley, J.M. Development of a Noninvasive System for Monitoring Dairy Cattle Sleep. J. Dairy. Sci. 2016, 99, 8477–8485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillard, C.; Meagher, R.K.; Von Keyserlingk, M.A.G.; Weary, D.M. Social Housing Improves Dairy Calves’ Performance in Two Cognitive Tests. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamanna, M.; Marliani, G.; Buonaiuto, G.; Cavallini, D.; Accorsi, P.A. Personality Traits of Dairy Cows: Relationship between Boldness and Habituation to Robotic Milking to Improve Precision and Efficiency. In Proceedings of the 11th European Conference on Precision Livestock Farming, Bologna, Italy, 9 September 2024; pp. 640–647. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes, A.; Yoon, S.; Park, J.; Park, D.S. Deep Learning-Based Hierarchical Cattle Behavior Recognition with Spatio-Temporal Information. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 177, 105627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukasawa, M.; Komatsu, T.; Higashiyama, Y.; Oshibe, A. The Use of Accelerometer to Measure Sleeping Posture of Beef Cows. Anim. Sci. J. 2018, 89, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ternman, E.; Pastell, M.; Agenäs, S.; Strasser, C.; Winckler, C.; Nielsen, P.P.; Hänninen, L. Agreement between Different Sleep States and Behaviour Indicators in Dairy Cows. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2014, 160, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, L.B.; O’Connor, C.; Haskell, M.J.; Langford, F.M.; Webster, J.R.; Stafford, K.J. Lying Posture Does Not Accurately Indicate Sleep Stage in Dairy Cows. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 242, 105427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesenti Rossi, G.; Dalla Costa, E.; Barbieri, S.; Minero, M.; Canali, E. A Systematic Review on the Application of Precision Livestock Farming Technologies to Detect Lying, Rest and Sleep Behavior in Dairy Calves. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1477731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattiello, S.; Battini, M.; De Rosa, G.; Napolitano, F.; Dwyer, C. How Can We Assess Positive Welfare in Ruminants? Animals 2019, 9, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaeffer, R.G.; Sikes, J.D. Discrimination Learning in Dairy Calves. J. Dairy. Sci. 1971, 54, 893–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, C.J.C.; Lomas, C.A. The Perception of Color by Cattle and Its Influence on Behavior. J. Dairy. Sci. 2001, 84, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manda, M.; Urata, K.; Noguchi, T.; Watanabe, S. Behavioral Study on Taste Responses of Cattle to Salty, Sour, Sweet, Bitter, Umami and Alcohol Solutions. Nihon Chikusan Gakkaiho 1994, 65, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginane, C.; Baumont, R.; Favreau-Peigné, A. Perception and Hedonic Value of Basic Tastes in Domestic Ruminants. Physiol. Behav. 2011, 104, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Set correlation and contingency tables. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1988, 12, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukasawa, M.; Komatsu, T.; Higashiyama, Y. Sleep and Lying Behavior of Milking Holstein Cows at Commercial Tie-Stall Dairy Farms. Anim. Sci. J. 2019, 90, 1313–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrousan, G.; Hassan, A.; Pillai, A.A.; Atrooz, F.; Salim, S. Early Life Sleep Deprivation and Brain Development: Insights from Human and Animal Studies. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 833786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, M.P.; Stickgold, R. Sleep-Dependent Learning and Memory Consolidation. Neuron 2004, 44, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagewoud, R.; Havekes, R.; Tiba, P.A.; Novati, A.; Hogenelst, K.; Weinreder, P.; Van der Zee, E.; Meerlo, P. Coping with Sleep Deprivation: Shifts in Regional Brain Activity and Learning Strategy. Sleep 2010, 33, 1456–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, M.; Iaria, G.; De Gennaro, L.; Guariglia, C.; Curcio, G.; Tempesta, D.; Bertini, M. The Role of Sleep in the Consolidation of Route Learning in Humans: A Behavioural Study. Brain Res. Bull. 2006, 71, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.E.; Chau, A.Q.; Olson, R.J.; Moore, C.; Wickham, P.T.; Puranik, N.; Guizzetti, M.; Cao, H.; Meshul, C.K.; Lim, M.M. Early Life Sleep Disruption Alters Glutamate and Dendritic Spines in Prefrontal Cortex and Impairs Cognitive Flexibility in Prairie Voles. Curr. Res. Neurobiol. 2021, 2, 100020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maquet, P. The Role of Sleep in Learning and Memory. Science 2001, 294, 1048–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, I.; Samuelsso, J.; Davidson, P. REM Sleep Improves Defensive Flexibility. In Proceedings of the Oral presentation at Proceedings of the International Psychological Applications Conference and Trends, Lisbon, Portugal, 30 April–2 May 2016; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Nagai, H.; De Vivo, L.; Bellesi, M.; Ghilardi, M.F.; Tononi, G.; Cirelli, C. Sleep Consolidates Motor Learning of Complex Movement Sequences in Mice. Sleep 2017, 40, zsw059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vorster, A.P.; Born, J. Sleep and Memory in Mammals, Birds and Invertebrates. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015, 50, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Kim, S.J.; Fujiyama, T.; Miyoshi, C.; Park, M.; Suzuki-Abe, H.; Yanagisawa, M.; Funato, H. The Role of Reproductive Hormones in Sex Differences in Sleep Homeostasis and Arousal Response in Mice. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 739236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iotchev, I.B.; Kis, A.; Bódizs, R.; Van Luijtelaar, G.; Kubinyi, E. EEG Transients in the Sigma Range during Non-REM Sleep Predict Learning in Dogs. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirano, P.D.; Algarín, C.R.; Peirano, P. Sleep in Brain Development. Biol. Res. 2007, 40, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalski, E.; Woodrum Setser, M.M.; Mazon, G.; Neave, H.W.; Costa, J.H.C. Personality of Individually Housed Dairy-Beef Crossbred Calves Is Related to Performance and Behavior. Front. Anim. Sci. 2022, 3, 1097503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neave, H.W.; Costa, J.H.C.; Weary, D.M.; von Keyserlingk, M.A.G. Personality Is Associated with Feeding Behavior and Performance in Dairy Calves. J. Dairy. Sci. 2018, 101, 7437–7449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberg, M.S.; Lesku, J.A.; Libourel, P.A.; Schmidt, M.H.; Rattenborg, N.C. What Is REM Sleep? Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, R38–R49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruyt, K.; Aitken, R.J.; So, K.; Charlton, M.; Adamson, T.M.; Horne, R.S.C. Relationship between Sleep/Wake Patterns, Temperament and Overall Development in Term Infants over the First Year of Life. Early Hum. Dev. 2008, 84, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arave, C.W.; Albright, J.L. Cattle Behavior. J. Dairy. Sci. 1981, 64, 1318–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krohn, C.C.; Munksgaard, L. Behaviour of Dairy Cows Kept in Extensive (Loose Housing/Pasture) or Intensive (Tie Stall) Environments II. Lying and Lying-down Behaviour. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1993, 37, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänninen, L. Sleep and Rest in Calves: Relationship to Welfare, Housing and Hormonal Activity; University of Helsinki, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Production Animal Medicine: Helsinki, Finland, 2007; ISBN 9789521036675. [Google Scholar]

- Haley, D.B.; Rushen, J.; De Passillé, A.M. Behavioural Indicators of Cow Comfort: Activity and Resting Behaviour of Dairy Cows in Two Types of Housing. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 1999, 80, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, B.K.; Schmidt, M.A.; Harvey, D.O.; Davis, C.J. Image Discrimination Reversal Learning Is Impaired by Sleep Deprivation in Rats: Cognitive Rigidity or Fatigue? Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 1052441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kis, A.; Szakadát, S.; Gácsi, M.; Kovács, E.; Simor, P.; Török, C.; Gombos, F.; Bódizs, R.; Topál, J. The Interrelated Effect of Sleep and Learning in Dogs (Canis familiaris); An EEG and Behavioural Study. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossi, G.; Perski, A.; Osika, W.; Savic, I. Stress-Related Exhaustion Disorder—Clinical Manifestation of Burnout? A Review of Assessment Methods, Sleep Impairments, Cognitive Disturbances, and Neuro-Biological and Physiological Changes in Clinical Burnout. Scand. J. Psychol. 2015, 56, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, J.M. Do All Animals Sleep? Trends Neurosci. 2008, 31, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghoubi, M. Evolution of Reward Coding in the Hippocampus During Learning. Ph.D. Thesis, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Russello, H.; van der Tol, R.; Holzhauer, M.; van Henten, E.J.; Kootstra, G. Video-Based Automatic Lameness Detection of Dairy Cows Using Pose Estimation and Multiple Locomotion Traits. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 223, 109040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawroth, C.; Rørvang, M.V. Opportunities (and Challenges) in Dairy Cattle Cognition Research: A Key Area Needed to Design Future High Welfare Housing Systems. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2022, 255, 105727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänninen, L.; De Passillé, A.M.; Rushen, J. The Effect of Flooring Type and Social Grouping on the Rest and Growth of Dairy Calves. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2005, 91, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Learned (Mean ± SD) | Not Learned (Mean ± SD) | Mean Difference (95% CI) | t (df) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| daily RSLP time (min/day) | 221.5 ± 69.4 | 218.9 ± 75.9 | −2.6 (−96.6, 91.3) | −0.07 (6) | 0.947 |

| RSLP frequency (bouts/day) | 33.9 ± 10.3 | 38.0 ± 10.7 | 4.1 (−9.2, 17.5) | 0.76 (6) | 0.478 |

| RSLP bout duration (min/bout) | 7.13 ± 2.31 | 5.84 ± 1.21 | −1.29 (−3.03, 0.45) | −1.60 (13) | 0.134 |

| ALR r (95% CI) | p-Value | RLR ρ (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| daily RSLP time (min/day) | −0.34 (−0.73, 0.21) | 0.218 | −0.56 (−0.85, −0.02) | 0.030 * |

| RSLP frequency (bouts/day) | −0.15 (−0.62, 0.39) | 0.586 | −0.33 (−0.73, 0.23) | 0.217 |

| RSLP bout duration (min/bout) | −0.17 (−0.63, 0.38) | 0.545 | −0.41 (−0.77, 0.16) | 0.131 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, S.; Fujita, N.; Sasaki, T.; Chiba, T.; Konno, S.; Roh, S.; Fukasawa, M. Associations Between REM Sleep-like Posture Expression and Cognitive Flexibility in 2-Month-Old Japanese Black Calves. Animals 2025, 15, 3438. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233438

Liu S, Fujita N, Sasaki T, Chiba T, Konno S, Roh S, Fukasawa M. Associations Between REM Sleep-like Posture Expression and Cognitive Flexibility in 2-Month-Old Japanese Black Calves. Animals. 2025; 15(23):3438. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233438

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Sita, Norihiro Fujita, Takako Sasaki, Takashi Chiba, Shinsuke Konno, Sanggun Roh, and Michiru Fukasawa. 2025. "Associations Between REM Sleep-like Posture Expression and Cognitive Flexibility in 2-Month-Old Japanese Black Calves" Animals 15, no. 23: 3438. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233438

APA StyleLiu, S., Fujita, N., Sasaki, T., Chiba, T., Konno, S., Roh, S., & Fukasawa, M. (2025). Associations Between REM Sleep-like Posture Expression and Cognitive Flexibility in 2-Month-Old Japanese Black Calves. Animals, 15(23), 3438. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233438