Low-Altitude UAV-Based Recognition of Porcine Facial Expressions for Early Health Monitoring

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

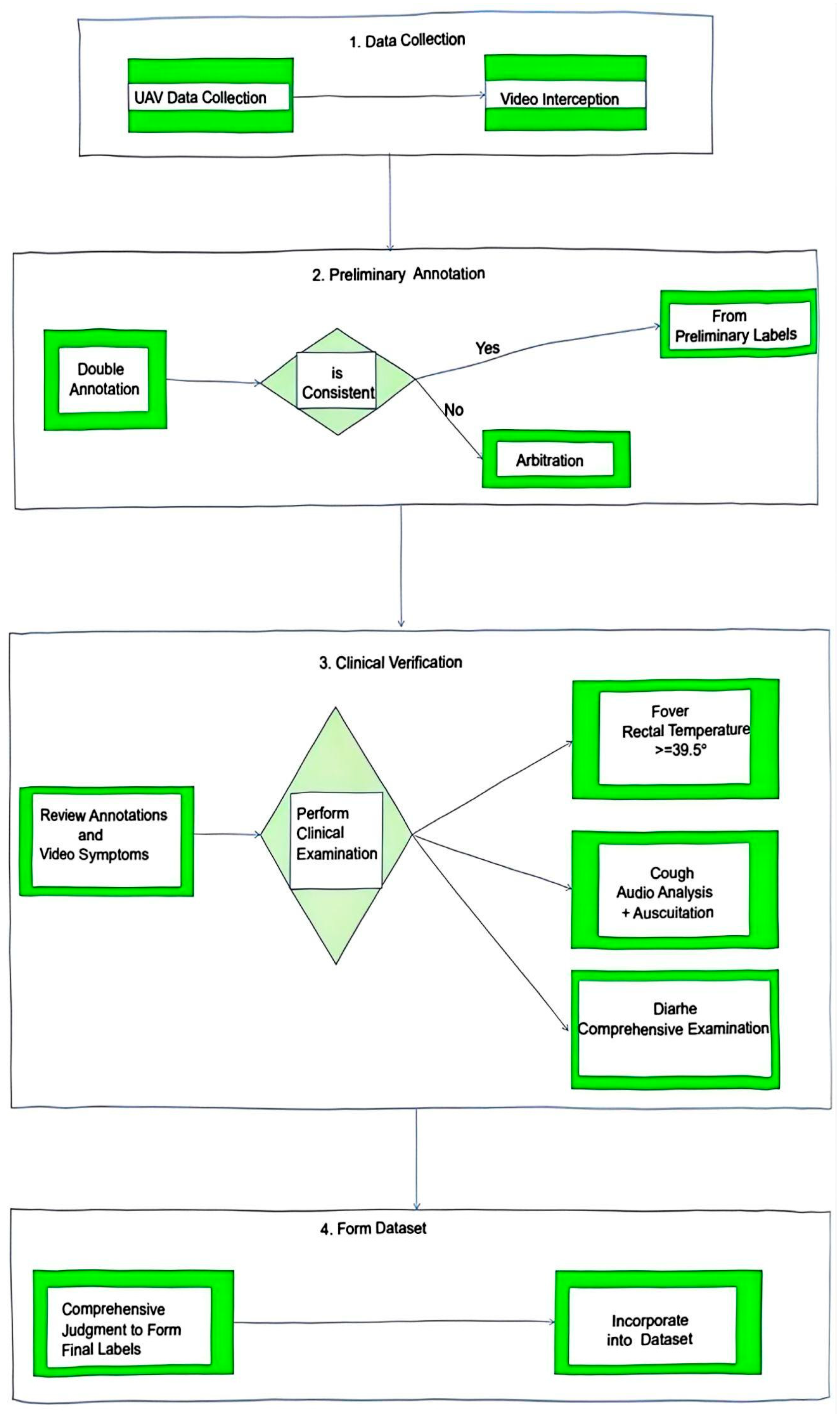

2.1. Research Content and Work

2.1.1. Data Collection Area and Sampling Period

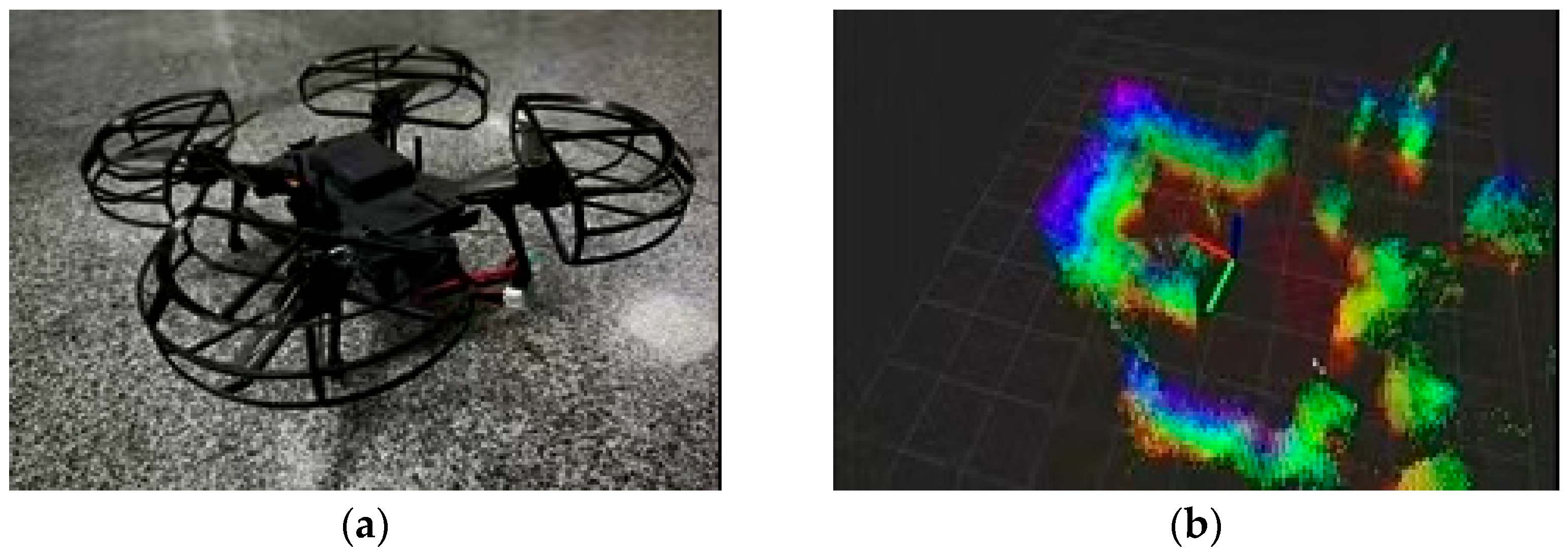

Data-Collection Equipment

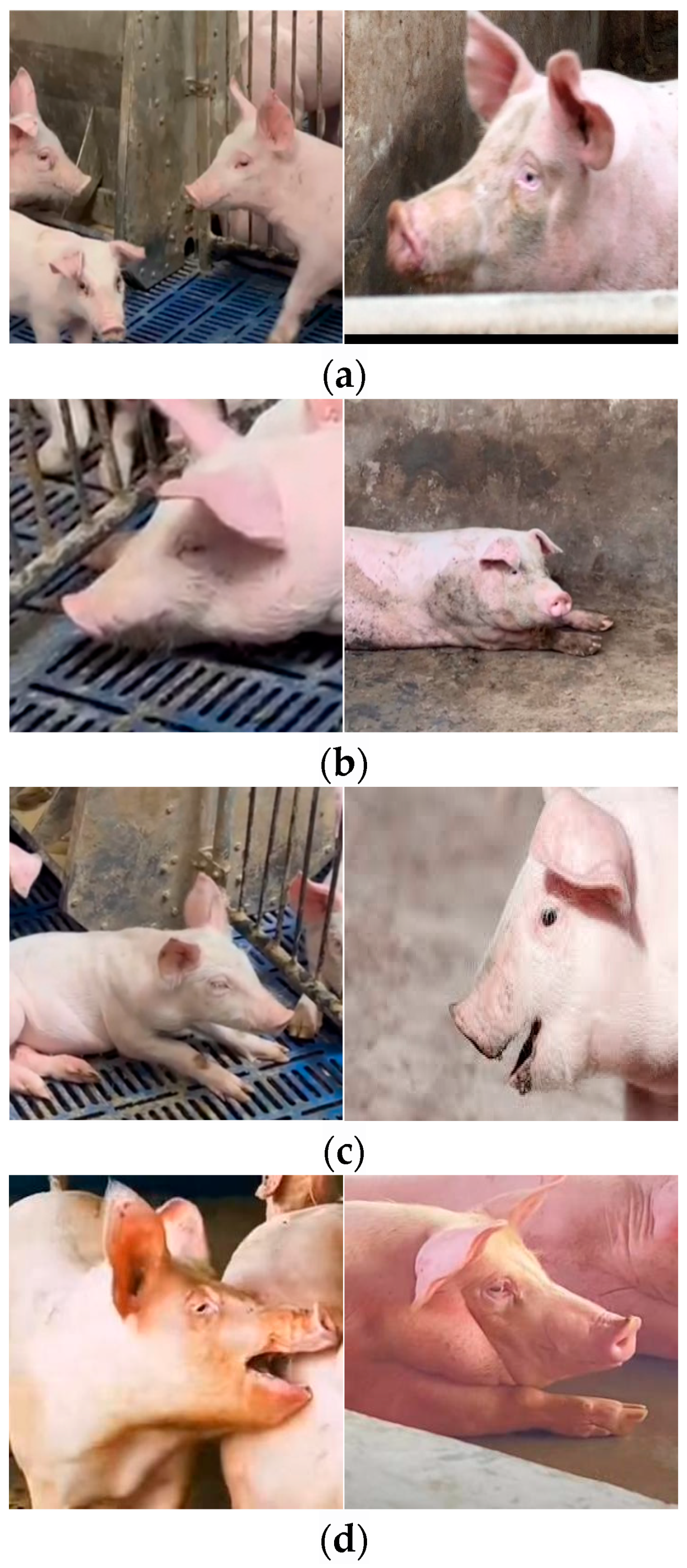

2.1.2. Facial-Expression Features in Pig Health States

2.1.3. Dataset Partitioning, Extension and Pre-Processing

- Standardization

- 2.

- Noise Mitigation

- 3.

- Multi-modal Augmentation

- 4.

- Dataset Partitioning

2.2. Training Environment Configuration

2.3. Model Overview

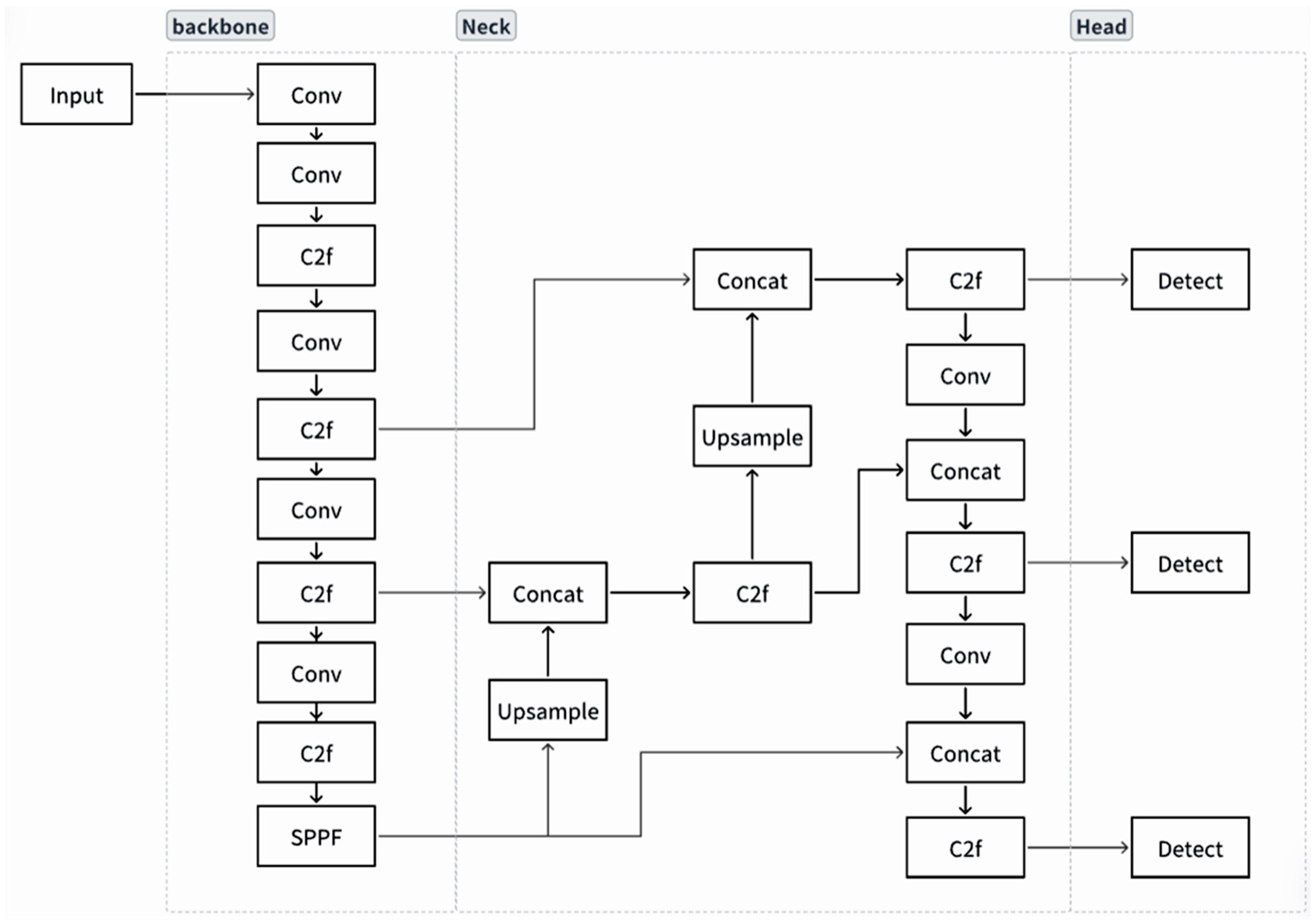

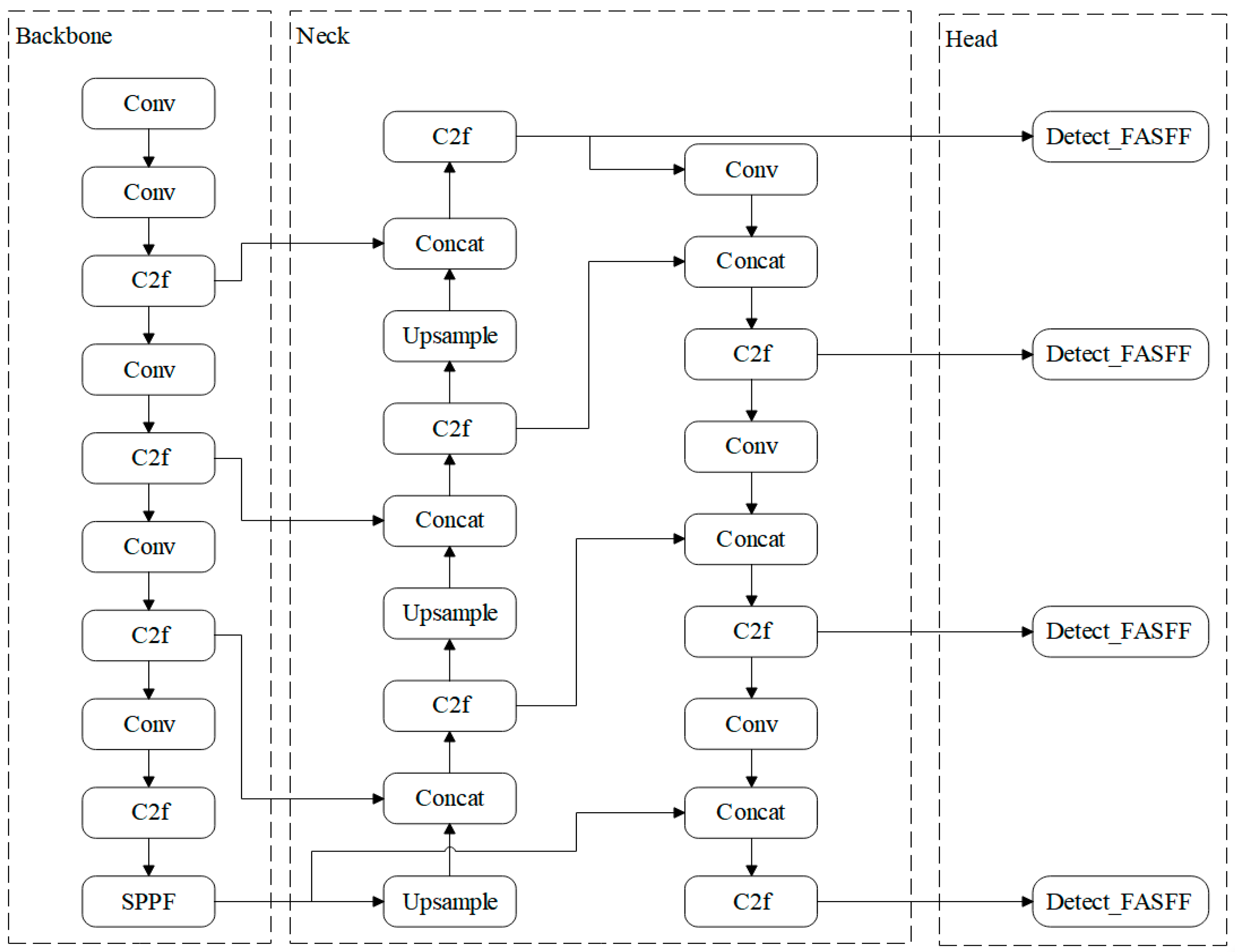

2.3.1. YOLOv8 Model

2.3.2. Detect_FASFF_YOLOv8

- Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- 2.

- Model Architecture Improvements:

- Spatial Alignment:

- 2.

- Co-attention Fusion:

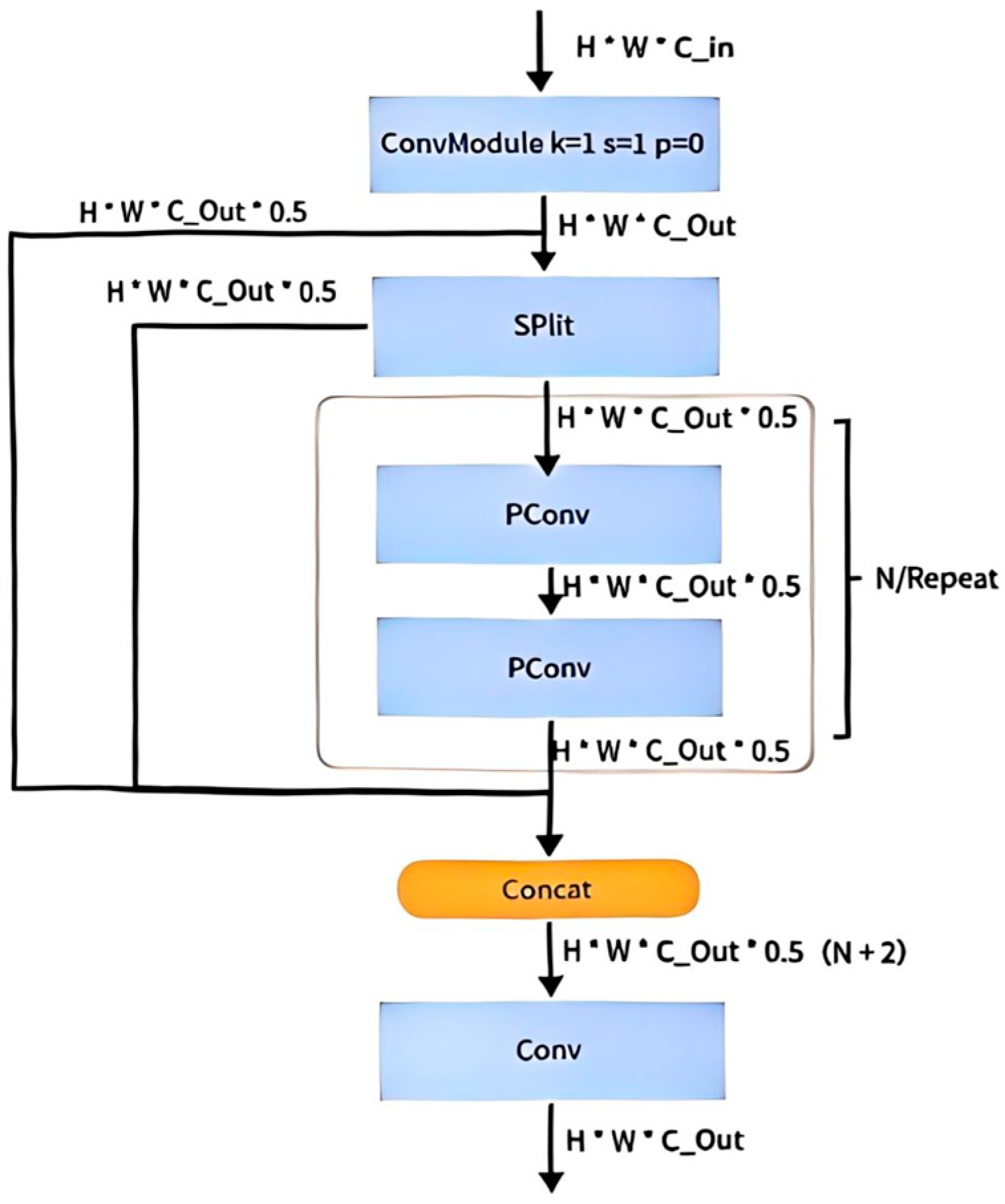

2.3.3. PartialConv_YOLOv8

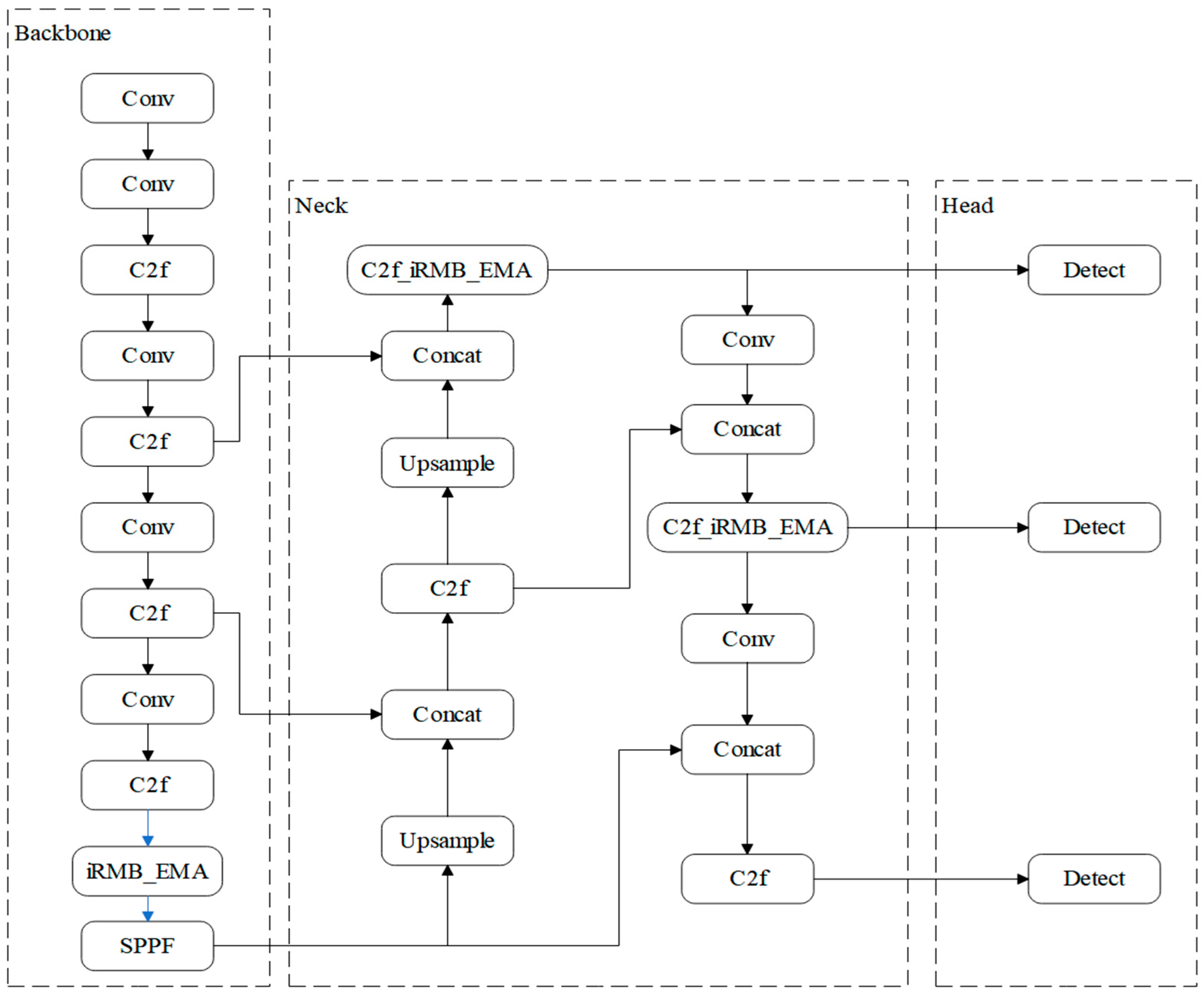

2.3.4. The iEMA_Attention Mechanism

Efficient Multi-Scale Attention (EMA)

Inverted Residual Mobile Block (iRMB)

The Secondary Integration Innovation of iEMA_Attention Mechanism

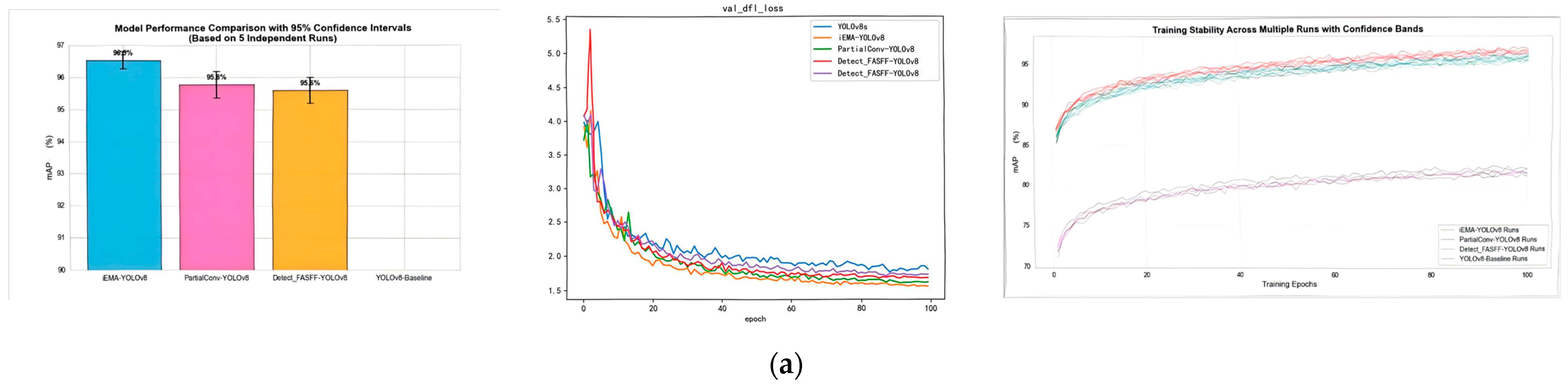

Ablation Study

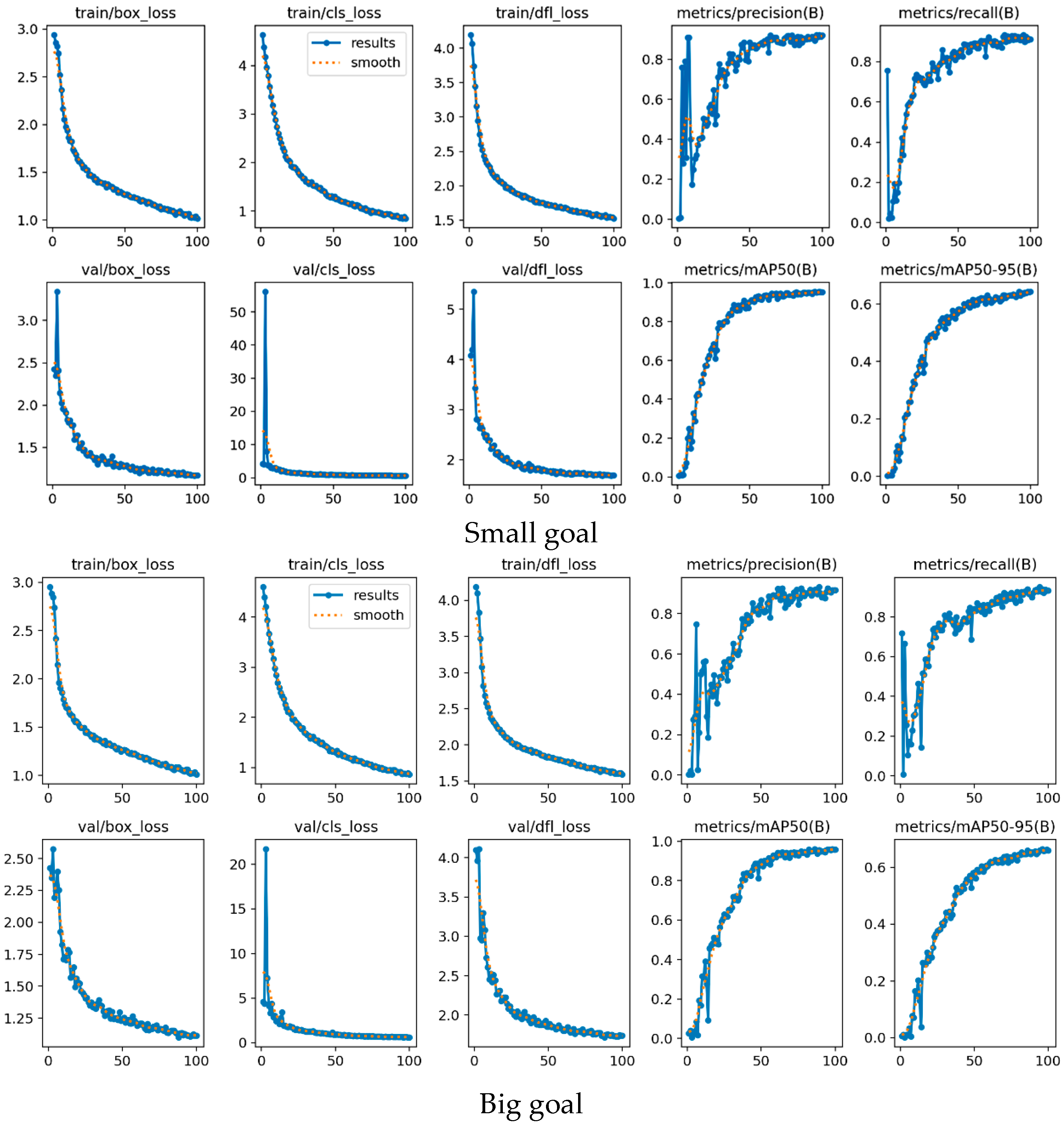

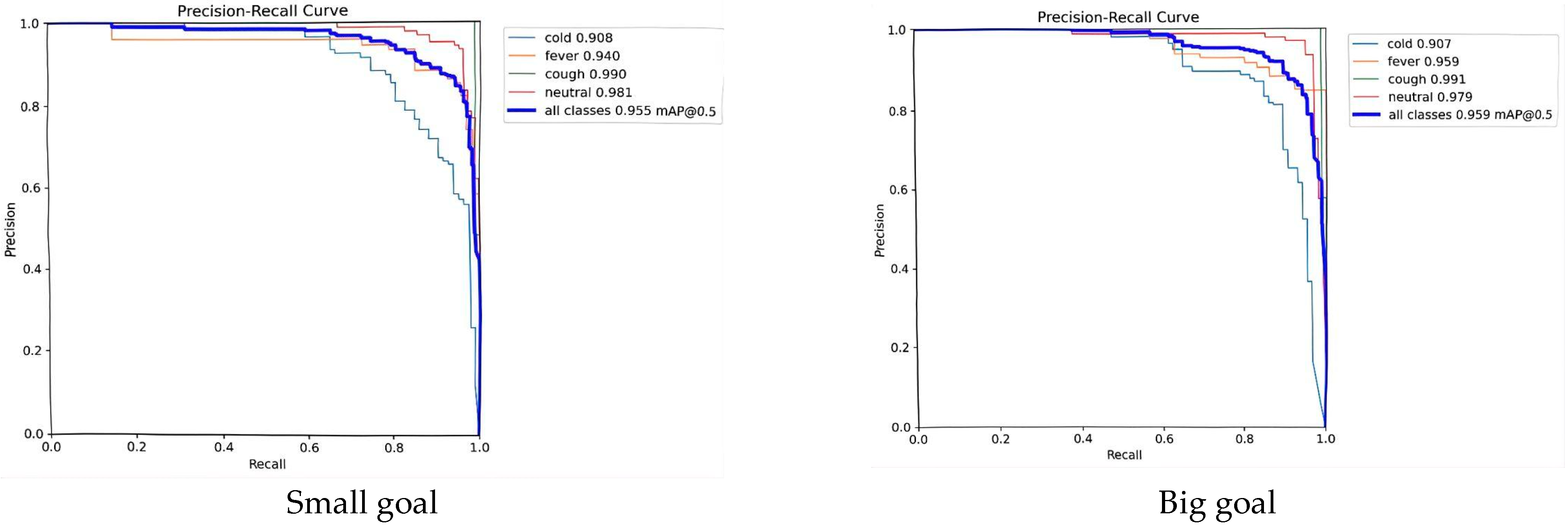

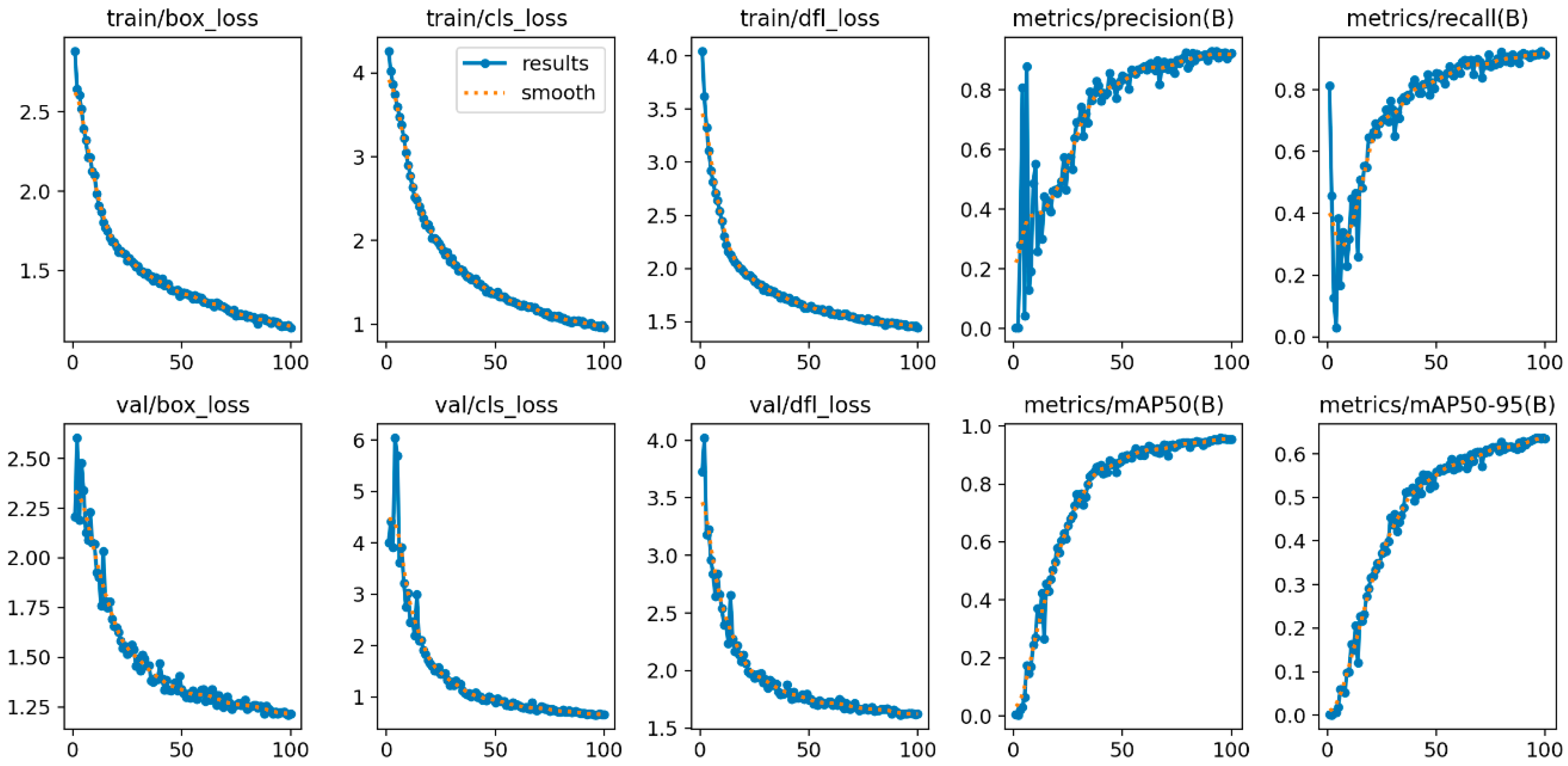

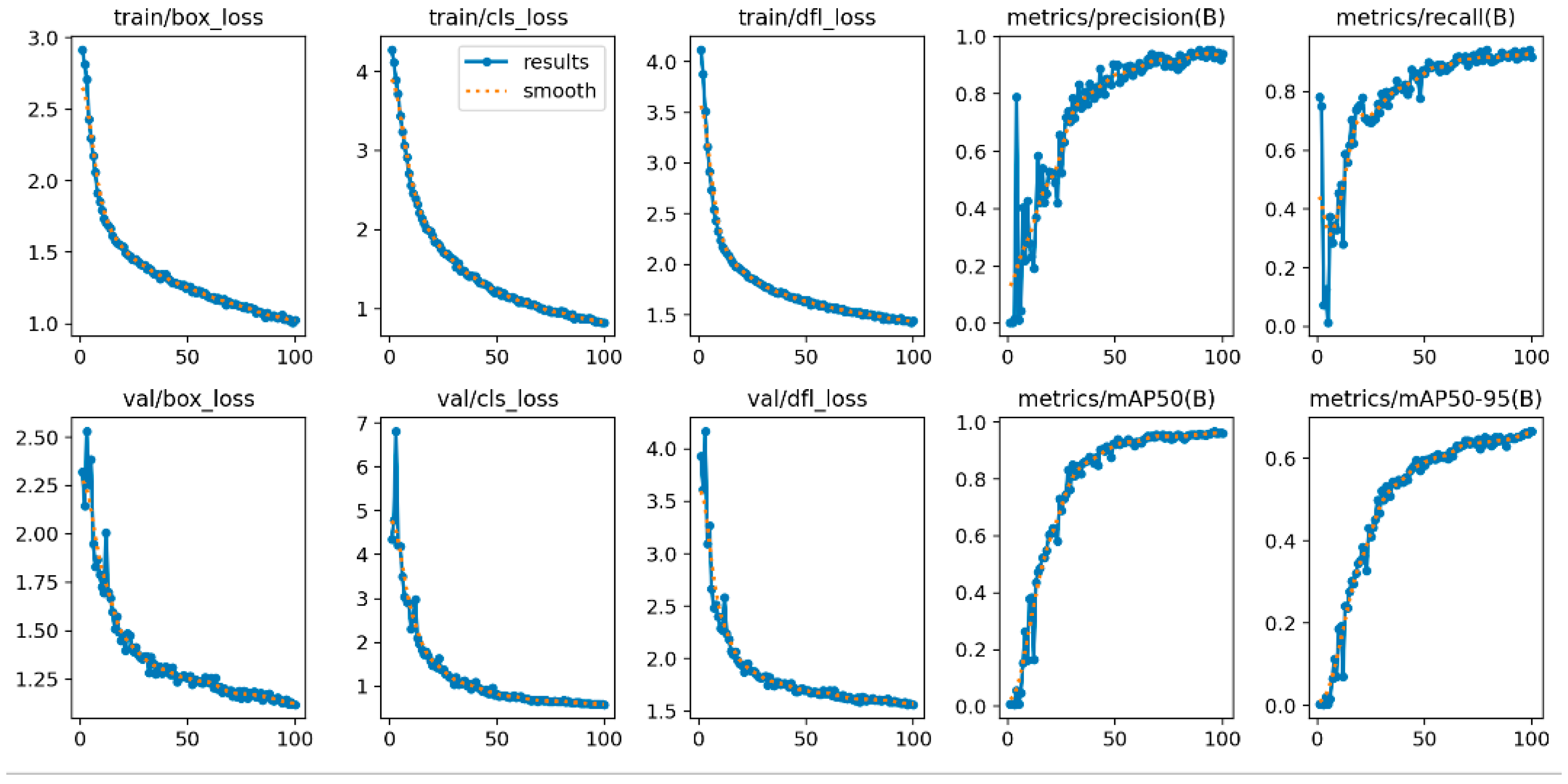

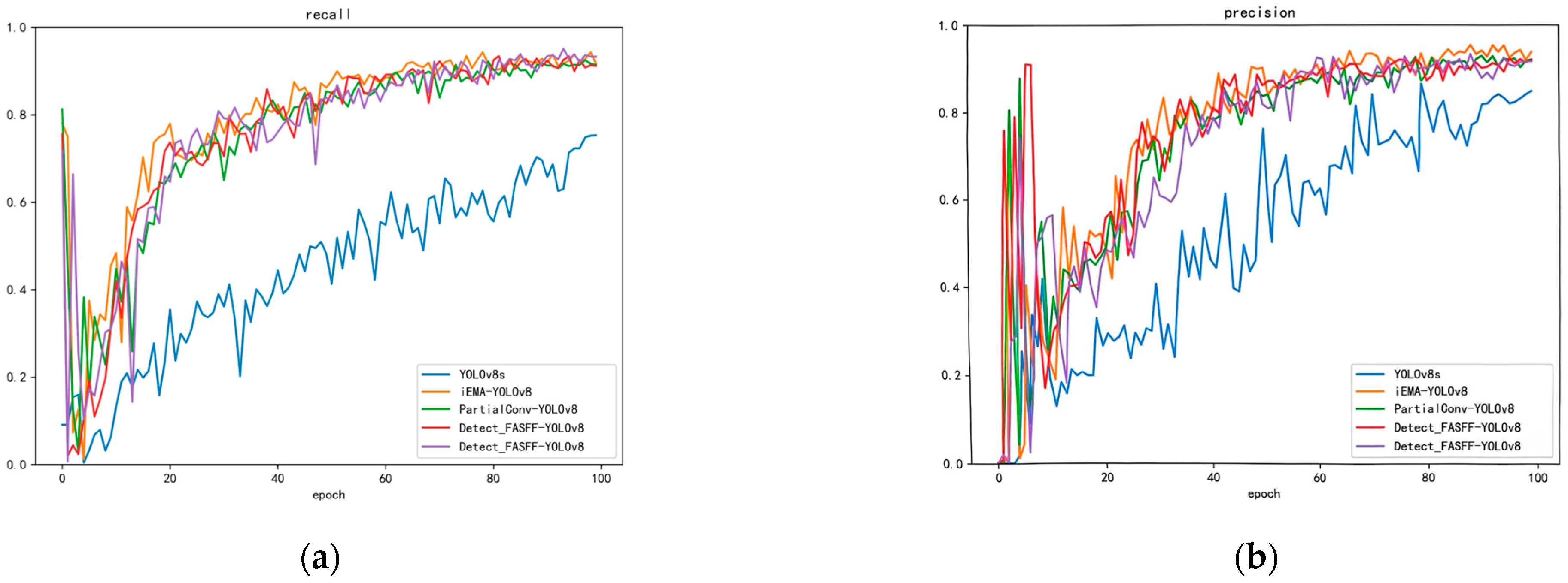

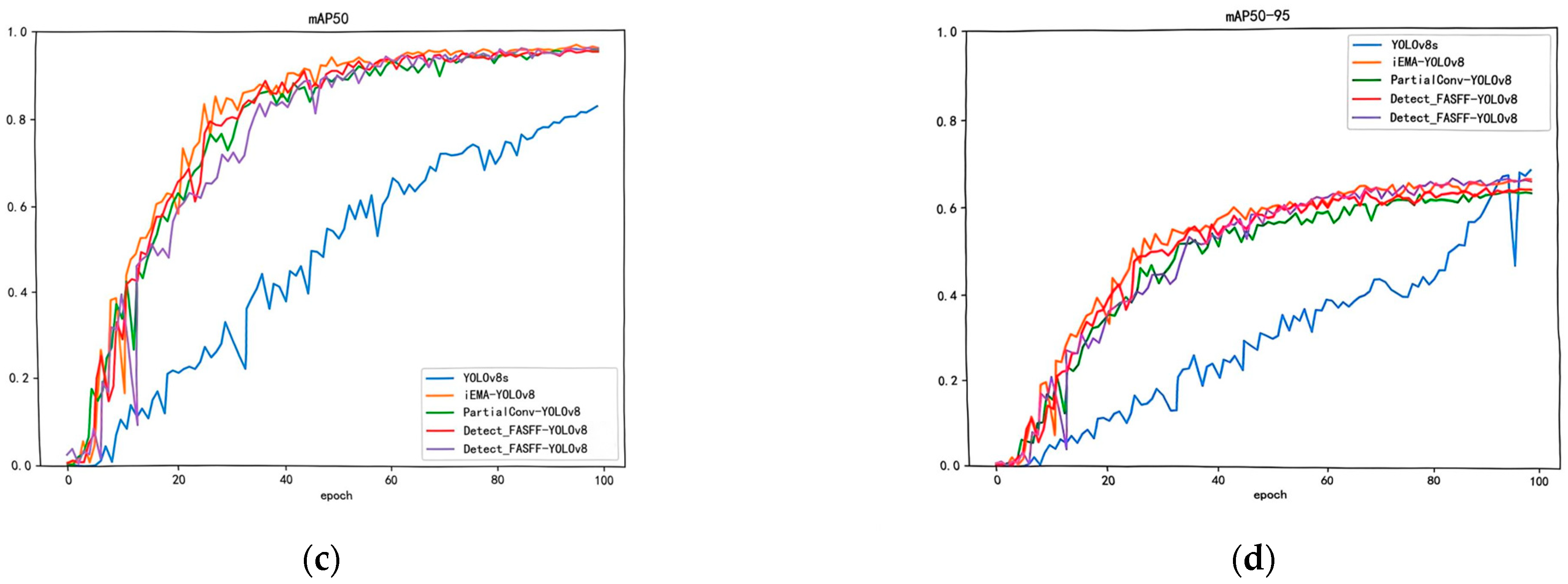

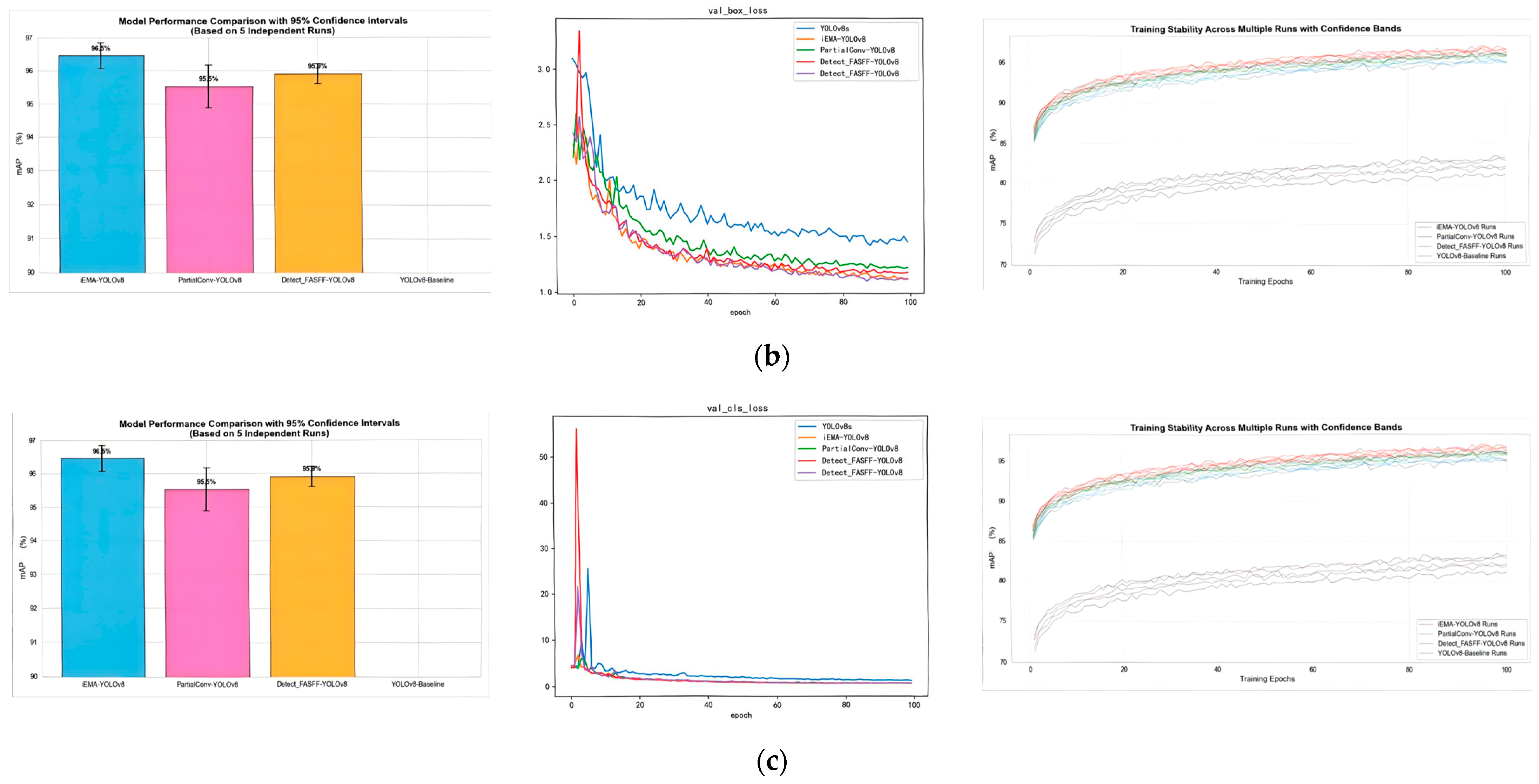

3. Results

Performance Comparison with Other YOLO Series Models

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, Y. Theoretical Foundation and System Construction of Farm Animal Welfare Labeling in China. J. Domest. Anim. Ecol. 2025, 46, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Feng, B.; Dai, Z.; Li, L.; Wei, H.; Zhang, S. Research Progress on the Mechanism and Application of Sow Appeasing Pheromone. Chin. J. Anim. Sci. 2025, 61, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zha, W.; Chen, C.; Shi, G.; Gu, L.; Jiao, J. A Pig Face Recognition and Detection Method Based on Improved YOLOv5s. Southwest China J. Agric. Sci. 2023, 36, 1346–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, P.; Yang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Li, H.M.; Hu, Z.W.; Cao, R.L.; Liu, Z.Y. Path Planning Optimization for Swine Manure-Cleaning Robots through Enhanced Slime Mold Algorithm with Cellular Automata. Anim. Sci. J. 2024, 95, e13992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsot, M.; Mei, J.; Shan, X.; Ye, L.; Feng, P.; Yan, X.; Li, C.; Zhao, Y. An Adaptive Pig Face Recognition Approach Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 173, 105386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, F.; Tao, H.; Gu, L.; Jiao, J. Pig Face Recognition Based on Improved YOLOv3. J. China Agric. Univ. 2021, 26, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, M.F.; Smith, M.L.; Smith, L.N.; Salter, M.G.; Baxter, E.M.; Farish, M.; Grieve, B. Towards On-Farm Pig Face Recognition Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Comput. Ind. 2018, 98, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Liu, Z.; Cui, Q.; Hu, Z.; Li, Y. Detection of Facial Orientation of Group-Housed Pigs Based on Improved Tiny-YOLO Model. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2019, 35, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psota, E.; Mittek, M.; Pérez, L.; Schmidt, T.; Mote, B. Multi-Pig Part Detection and Association with a Fully-Convolutional Network. Sensors 2019, 19, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannone, C.; Sahraeibelverdy, M.; Lamanna, M.; Cavallini, D.; Formigoni, A.; Tassinari, P.; Torreggiani, D.; Bovo, M. Automated Dairy Cow Identification and Feeding Behaviour Analysis Using a Computer Vision Model Based on Yolov8. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 12, 101304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.P.; Hagemoser, W.A.; Kluge, J.P.; Hill, H.T. Pathogenesis of ovine pseudorabies (Aujeszky’s disease) following intratracheal inoculation. Can. J. Vet. Res. 1987, 51, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Müller, R.B.; Soriano, S.V.; Bellio, B.C.J.; Molento, C.F.M. Facial expression of pain in Nellore and crossbred beef cattle. J. Vet. Behav. 2019, 34, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Knörr, A.; Morante, B.G.; Correia-Gomes, C.; Pérez, L.D.; Segalés, J.; Sibila, M.; Vilalta, C.; Burrell, A.; Bearth, A.; et al. Data recording and use of data tools for pig health management: Perspectives of stakeholders in pig farming. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 11, 1490770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, B.; Li, H.; Chen, M.; Song, Y.; Liu, Z. A Lightweight Decision-Level Fusion Model for Pig Disease Identification Using Multi-Modal Data. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 231, 109936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, Y.; Yan, B.; Zou, M.; Xu, J. A Lightweight Cattle Face Recognition Model Based on Improved YOLOv8s. J. Chin. Agric. Mech. 2025, 46, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, R.; Wang, Z.; Feng, J.; Cao, R.; Hu, G.; Liu, Z. Real-Time Pig Weight Assessment and Carbon Footprint Monitoring Based on Computer Vision. Animals 2025, 15, 2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Xu, T.; Shi, C.; Li, S.; Xie, Q.; Rong, L. Research on Pig Behavior Recognition Method Based on CBCW-YOLO v8. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2025, 56, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wang, X.; Cao, R.; Hu, G.; Liu, Z. Integrated Convolution and Attention Enhancement-You Only Look Once: A Lightweight Model for False Estrus and Estrus Detection in Sows Using Small-Target Vulva Detection. Animals 2025, 15, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, H.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Yang, C. A Review of YOLO Algorithm Applications in Plant and Animal Phenotype Research. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2024, 55, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, J.; Hu, W.; Zhang, K. A Lightweight Target Detection Method for Thermal Defects in Smart Meters Based on YOLO-MCSL. Chin. J. Sci. Instrum. 2025, 46, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Yang, J.; Xu, D. Recognition of Cattle Breeds and Behaviors Based on Improved YOLO v10. J. South China Agric. Univ. 2025, 46, 832–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, L.; Shi, J. A Pool Drowning Detection Model Based on Improved YOLO. Sensors 2025, 25, 5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Cheng, G.; Yang, L.; Han, S.; Wang, Y.; Dai, X.; Fang, J.; Wu, J. Method for Dairy Cow Target Detection and Tracking Based on Lightweight YOLO v11. Animals 2025, 15, 2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Gu, X. Investigation on Welfare Issues, Abnormal Behaviors and Mitigation Measures in Growing-Finishing Pigs. J. Domest. Anim. Ecol. 2025, 46, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Zhang, X.; Wu, J.; Yang, C.; Li, Z.; Shi, L.; Yu, H. Recognition of Pig Facial Expressions Based on Multi-Attention Mechanism Cascaded LSTM Model. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2021, 37, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhang, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Q. Research on Rice Leaf Disease Detection Based on Improved YOLOv8n Algorithm. Shandong Agric. Sci. 2025, 57, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yin, Z.; Duan, Y.; Cao, R.; Hu, G.; Liu, Z. Research on Improved Sound Recognition Model for Oestrus Detection in Sows. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 231, 109975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnotta, M.; Psujek, M.; Straffon, M.L.; Fusaroli, R.; Tylén, K. Drawing Animals in the Paleolithic: The Effect of Perspective and Abbreviation on Animal Recognition and Aesthetic Appreciation. Top. Cogn. Sci. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, S.; Sharif, M.; Cheng, X.; Kadry, S. Suspicious action recognition in surveillance based on handcrafted and deep learning methods: A survey of the state of the art. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 120, 109811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.R.; Singh, N.P.; Pantola, D.; Cheng, X. Neural network developments: A detailed survey from static to dynamic models. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 120, 109710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Yan, R.; Cui, H.; Cheng, X.; Li, J.; Wu, F.; Yin, Z.; Wang, H.; Zeng, W.; Yu, X. A hierarchical method for locating the interferometric fringes of celestial sources in the visibility data. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 2024, 24, 035011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Status | Nose Condition | Eye Condition | Mouth and Respiration | Overall Expression | Clinical Validation and Objective Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | Moist and glossy | Bright, no discharge | Naturally closed, smooth breathing | Relaxed, alert | Physical examination shows no abnormalities Rectal temperature: 38.5–39.4 °C |

| Cold | Dry, runny nose | Slight swelling, tear traces | Mouth half-open to aid breathing, nasal congestion | Low-spirited, listless | Veterinarians conduct comprehensive physical examinations Exclude other primary respiratory diseases |

| Fever | Dry, cracked | Conjunctival congestion, listless | Mouth half-open, gas exhaled hot | Lethargic, unfocused gaze | Rectal temperature ≥ 39.5 °C |

| Cough | Possible sputum spray | Eyes shut when coughing, restless | Open mouth while coughing, throat constriction | Spasmodic coughing, watery discharge | Audio analysis confirms cough spectrum characteristics Veterinary auscultation reveals abnormal respiratory sounds Clinical examination eliminates environmental stimuli (such as dust) |

| Health State | Training Set (n) | Validation Set (n) | Test Set (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 950 | 275 | 175 |

| Cold | 950 | 275 | 175 |

| Cough | 950 | 275 | 175 |

| Fever | 950 | 275 | 175 |

| Total | 3800 | 1100 | 700 |

| Model Variant | Spatial Alignment | Co-Attention | mAP50 (%) | FLOPs (G) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (YOLOv8s) | - | - | 82.1 | 20.6 |

| FASFF w/Naive Fusion | √ | - | 91.8 (+9.7) | 18.1 |

| FASFF w/Alignment Only | √ | - | 92.5 (+10.4) | 18.8 |

| FASFF (Full) | √ | √ | 95.5 (+13.4)/95.9 (+13.8) | 15.2/10.2 |

| Module | Convolution Type | Parameter Count | Calculation Volume (FLOPs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Original C2f bottleneck | 3 × 3 Standard Conv | C × C × 9 | C × C × 9 × H × W |

| Lightweight C2f bottleneck | 3 × 3 Partial Conv | (C/2 × C/2 × 9) × 2 | The original calculation quantity 1/2 |

| Model Configuration | EMA | iRMB | mAP50 (%) | ΔmAP | Params (M) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline + FASFF | - | - | 95.5 | - | 11.2 |

| Variant A | - | √ | 95.8 | +0.3 | 11.4 |

| Variant B | √ | - | 96.1 | +0.6 | 11.6 |

| iEMA_Attention (Full) | √ | √ | 96.4 | +0.9 | 11.8 |

| Model | mAP50 (%) | mAP50–95 (%) | FLOPs (G) | Recall | Box (p) | |||

| Detect_FASFF_YOLOv8 (Small goal) (Big goal) | \ 0.955 0.959 | \ 0.643 0.664 | \ 15.2 10.2 | \ 0.928 0.939 | \ 0.916 0.92 | |||

| YOLOv5s YOLOv8s | 0.76 0.821 | 0.698 0.684 | 23.8 20.6 | 0.729 0.753 | 0.818 0.846 | |||

| YOLOv11s | 0.926 | 0.682 | 13.6 | 0.902 | 0.918 | |||

| YOLOv12s YOLOv13s | 0.934 0.942 | 0.679 0.662 | 7.8 7.1 | 0.916 0.923 | 0.927 0.936 | |||

| Faster R_CNN | 0.921 | 0.65 | 169.7 | 0.906 | 0.845 | |||

| Rt_Detr | 0.888 | 0.566 | 103.4 | 0.833 | 0.826 | |||

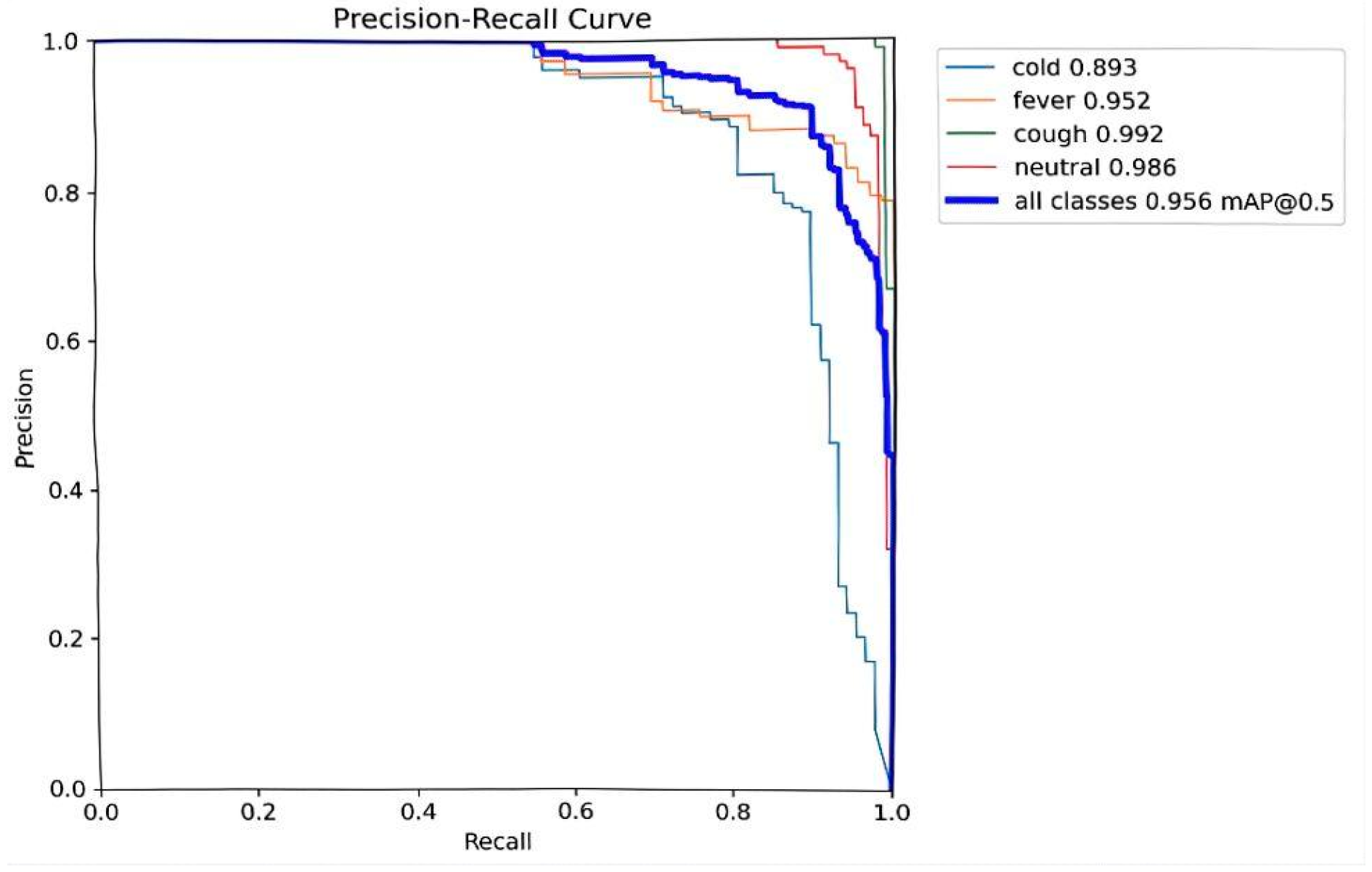

| PartialConv_YOLOv8 | 0.956 | 0.637 | 6.0 | 0.916 | 0.919 | |||

| YOLOv5s YOLOv8s | 0.76 0.821 | 0.698 0.684 | 23.8 20.6 | 0.729 0.753 | 0.818 0.846 | |||

| YOLOv11s | 0.926 | 0.682 | 13.6 | 0.902 | 0.918 | |||

| YOLOv12s YOLOv13s | 0.934 0.942 | 0.679 0.662 | 7.8 7.1 | 0.916 0.923 | 0.927 0.936 | |||

| Faster R_CNN | 0.921 | 0.65 | 169.7 | 0.906 | 0.845 | |||

| Rt_Detr | 0.888 | 0.566 | 103.4 | 0.833 | 0.826 | |||

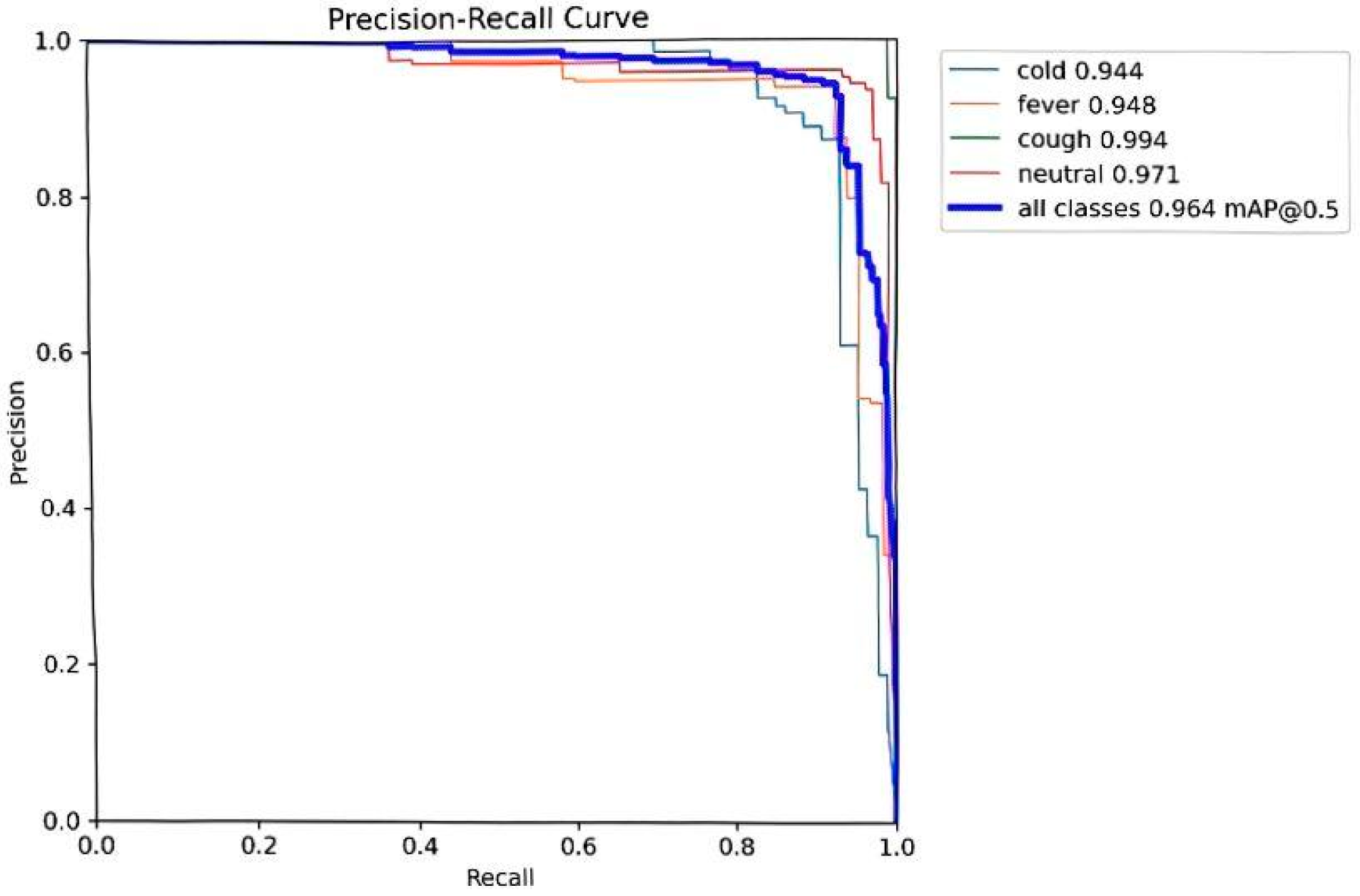

| iEMA_YOLOv8 | 0.964 | 0.665 | 8.3 | 0.943 | 0.92 | |||

| YOLO 5s YOLOv8s | 0.76 0.821 | 0.698 0.684 | 23.8 20.6 | 0.729 0.753 | 0.818 0.846 | |||

| YOLOv11s | 0.926 | 0.682 | 13.6 | 0.902 | 0.918 | |||

| YOLOv12s YOLOv13s | 0.934 0.942 | 0.679 0.662 | 7.8 7.1 | 0.916 0.923 | 0.927 0.936 | |||

| Faster R_CNN | 0.921 | 0.65 | 169.7 | 0.906 | 0.845 | |||

| Rt_Detr | 0.888 | 0.566 | 103.4 | 0.833 | 0.826 | |||

| Model | mAP50 (%) | mAP50–95 (%) | FLOPs (G) | Recall | Box (p) | Params (M) | Latency (ms) | FPS |

| Proposed Models | ||||||||

| iEMA_YOLOv8 PartialConv_YOLOv8 Detect_FASFF_YOLOv8 | 0.964 0.956 0.955/0.959 | 0.665 0.637 0.643/0.664 | 8.3 6.0 15.2/10.2 | 0.943 0.916 0.928/0.939 | 0.92 0.919 0.916/0.92 | 11.8 6.6 11.2/10.3 | 12.1 ± 0.8 8.2 ± 0.4 10.5/10.3 ± 0.6 | 82.6 121.9 95.2/97.1 |

| Baseline Models | ||||||||

| YOLOv5s YOLOv8s | 0.76 0.821 | 0.698 0.684 | 23.8 20.6 | 0.729 0.753 | 0.818 0.846 | 16.1 12.8 | 20.4 16.7 | 49.1 59.8 |

| YOLOv11s | 0.926 | 0.682 | 13.6 | 0.902 | 0.918 | 10.5 | 10.6 | 94.3 |

| YOLOv12s YOLOv13s | 0.934 0.942 | 0.679 0.662 | 7.8 7.1 | 0.916 0.923 | 0.927 0.936 | 6.9 6.5 | 8.8 7.9 | 113.6 126.6 |

| Faster R_CNN | 0.921 | 0.65 | 169.7 | 0.906 | 0.845 | 52.8 | 46.8 | 21.5 |

| Rt_Detr | 0.888 | 0.566 | 103.4 | 0.833 | 0.826 | 31.9 | 35.5 | 28.2 |

| Model | Normal (AP%) | Cold (AP%) | Cough (AP%) | Fever (AP%) | mAP50 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iEMA_YOLOv8 | 97.1 | 94.4 | 99.4 | 94.8 | 96.4 |

| PartialConv_YOLOv8 | 98.6 | 89.3 | 99.2 | 95.2 | 95.6 |

| Detect_FASFF_YOLOv8 | 98.1/97.9 | 90.8/90.7 | 99.0/99.1 | 94.0/95.9 | 0.955/95.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Mi, R.; Liu, H.; Yi, M.; Fan, Y.; Hu, G.; Liu, Z. Low-Altitude UAV-Based Recognition of Porcine Facial Expressions for Early Health Monitoring. Animals 2025, 15, 3426. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233426

Wang Z, Mi R, Liu H, Yi M, Fan Y, Hu G, Liu Z. Low-Altitude UAV-Based Recognition of Porcine Facial Expressions for Early Health Monitoring. Animals. 2025; 15(23):3426. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233426

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhijiang, Ruxue Mi, Haoyuan Liu, Mengyao Yi, Yanjie Fan, Guangying Hu, and Zhenyu Liu. 2025. "Low-Altitude UAV-Based Recognition of Porcine Facial Expressions for Early Health Monitoring" Animals 15, no. 23: 3426. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233426

APA StyleWang, Z., Mi, R., Liu, H., Yi, M., Fan, Y., Hu, G., & Liu, Z. (2025). Low-Altitude UAV-Based Recognition of Porcine Facial Expressions for Early Health Monitoring. Animals, 15(23), 3426. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15233426