2. Materials and Methods

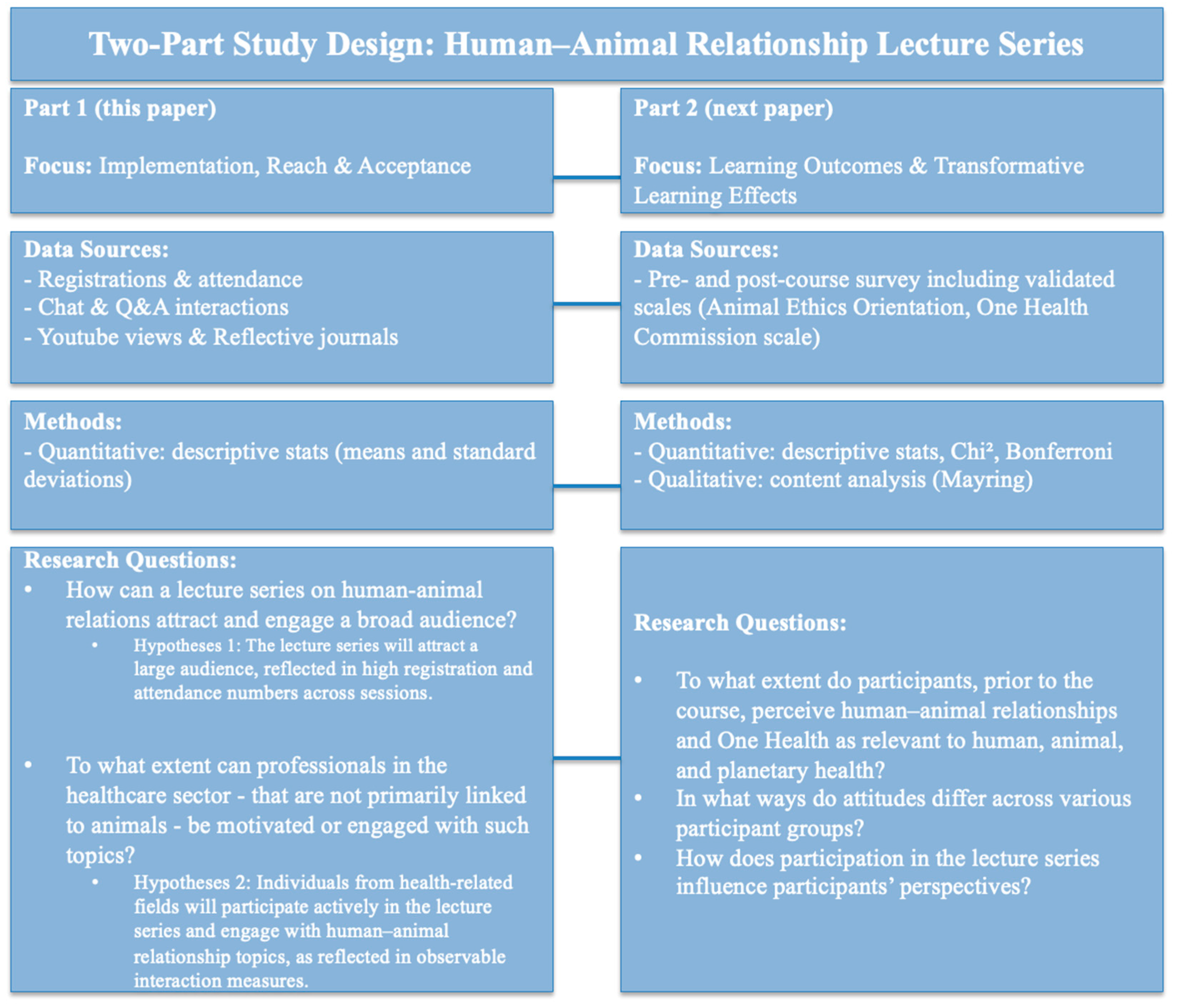

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the ethics committee of UW/H (reference number 186/2024). The following methodology was applied to address the research questions. As outlined above, this project is a two-part study. While Part 1 (this paper) reports on implementation, reach, and acceptance, Part 2 will present pre–post survey results on participants’ learning outcomes.

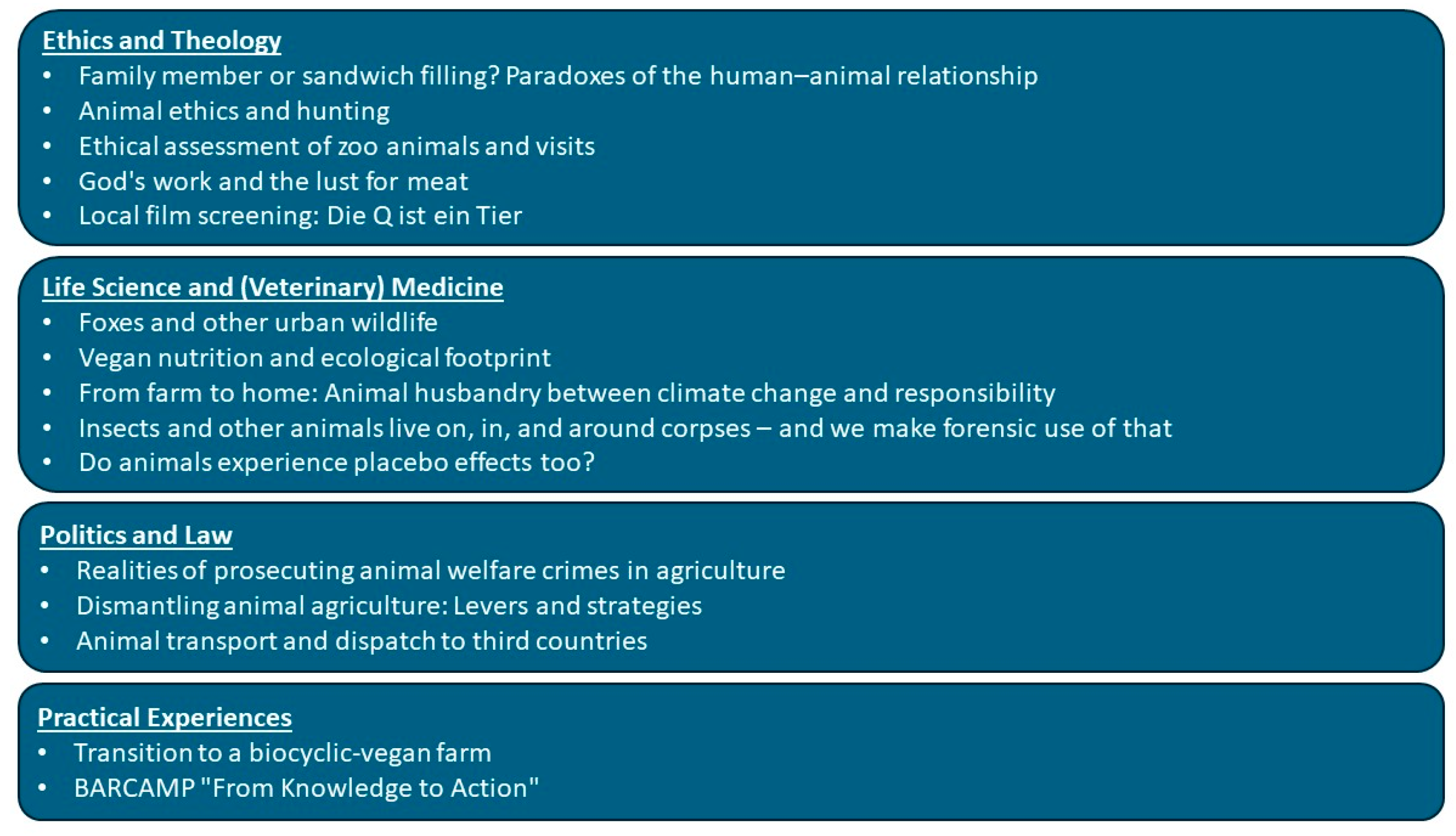

Figure 2 summarizes the overall study design.

2.1. Theoretical Framework: Transformative Learning Theory

The lecture series is conceptually grounded in Mezirow’s Transformative Learning Theory, which posits that deep learning occurs through critical reflection on previously held assumptions [

39]. This process is often initiated by ethically or emotionally challenging content and fosters lasting shifts in perspective and behavior [

40]. Interdisciplinary and values-based formats—such as those combining sustainability and social justice topics—create a “third space” in which diverse perspectives meet, enabling reflective discourse and co-constructed knowledge that effectively trigger transformative learning outcomes [

41,

42].

2.2. Participants

The course was open to both students at UW/H and external participants, including students from other universities and members of the public. This open-access structure broadened the range of perspectives and facilitated wider societal engagement. The diversity shown in both the most common study programs and locations of the participants, as illustrated in

Table 4 and

Table 5, emphasize how the series attracted attendees from many academic backgrounds and locations. External students were able to request certification of participation from the instructors and seek academic credit at their home institutions. No restrictions were placed on the participants’ field of study or academic level.

2.3. Data Collection

The evaluation of the lecture series followed a mixed-methods approach, incorporating both quantitative and qualitative data collection strategies. This paper focuses specifically on the quantitative findings.

Participant engagement was continuously documented through the total number of registrations and weekly attendance records.

A key element of data collection involved the analysis of interaction metrics within the Zoom platform. These included the number of questions submitted via the Q&A (questions and answers) function, as well as chat messages exchanged during discussions—both between participants and in communication with speakers and facilitators. In addition, the number of live polls conducted during each session and the corresponding number of responses were recorded as indicators of active participation.

Public engagement with the lecture series was also assessed via YouTube analytics, capturing the number of views of recorded sessions.

As part of course requirements, some participants submitted reflective learning journals that documented their personal insights and critical reflections over the course of the series each in relation to a specific lecture. Reflective journals were optional for attendees and required additional time after sessions, which likely contributed to lower submission rates relative to live interaction metrics. These served as a qualitative complement to the quantitative analysis, offering insight into individual learning processes and participant perceptions.

2.4. Data Analysis

Participant data were exported from Zoom and initially sorted and cleaned in Excel (e.g., removal of duplicate entries). The cleaned dataset was then imported into SPSS (Version 29.0, IBM Corporation, 233 S. Wacker Drive, 11th Floor, Chicago, IL 60606-6307, USA), where descriptive statistical analyses were conducted to summarize central participation and engagement metrics. Participation reach and engagement were assessed by examining both cumulative and session-specific attendance data.

Interaction rates—including chat activity, Q&A submissions, poll participation, and attendance at the Barcamp workshop—were analyzed quantitatively to evaluate levels of active involvement.

In addition, the number of YouTube views and submitted learning journals were considered as complementary indicators of content engagement and personal reflection.

This multi-layered analysis aimed to assess the extent to which the lecture series functioned as an effective educational format for One Health, and to identify the key factors that supported interactive participation and meaningful content engagement. The findings are intended to inform future development of interdisciplinary teaching models and to contribute to the design of innovative educational formats in the field of human–animal relations and One Health.

4. Discussion

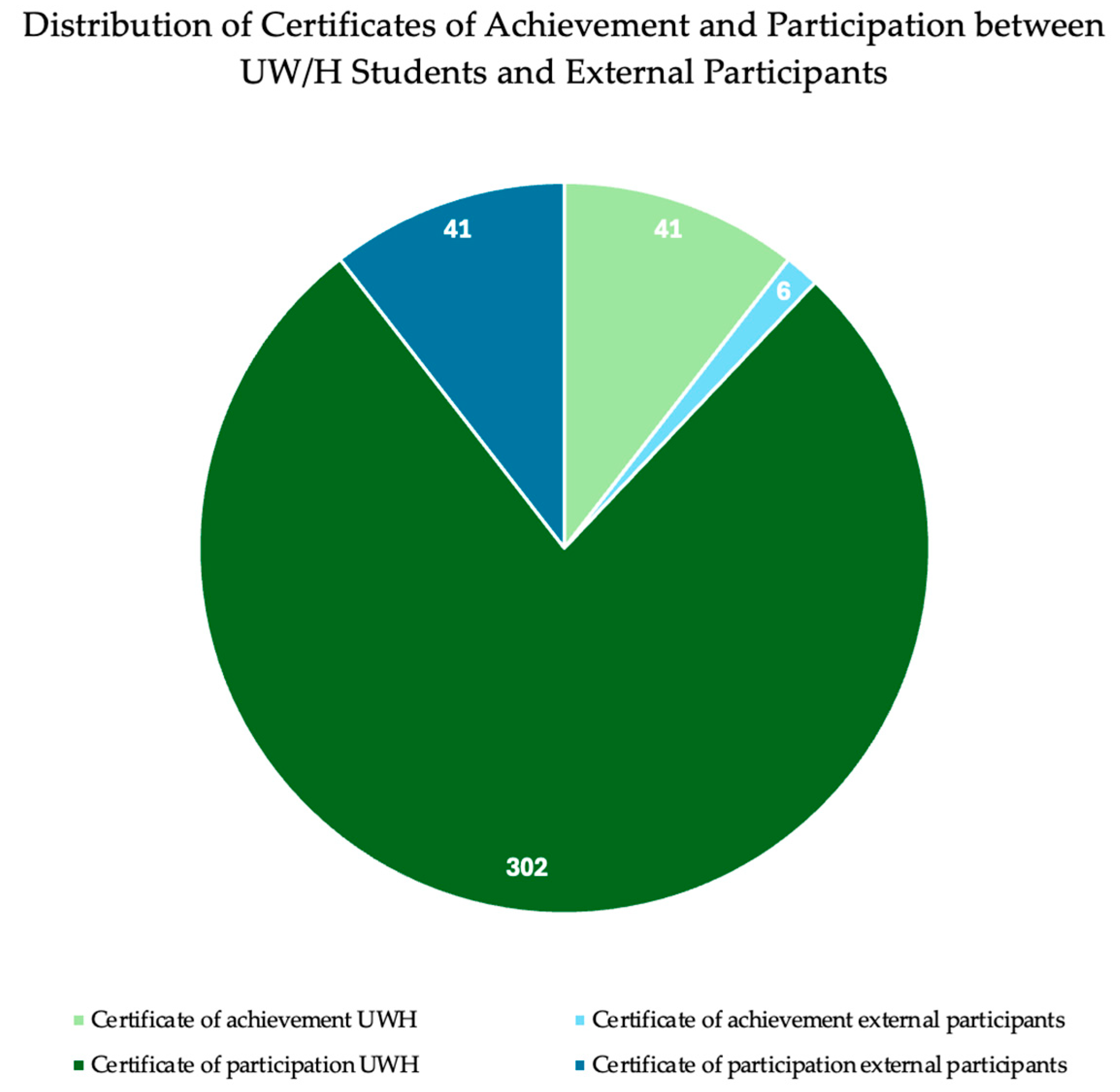

This manuscript reports on the development and implementation of the lecture series “Human–Animal Relationship”, offered at UW/H as an educational format open to both internal students and external participants, including students from other universities and members of the general public. Organized and moderated by three faculty members, the series spanned four months and featured weekly expert-led lectures, a Barcamp workshop, and a film screening. The event was conducted digitally via Zoom and accompanied by a scientific evaluation aimed at assessing its effectiveness in terms of knowledge acquisition and changes in participant perspectives. A mixed-methods approach was used to collect a wide range of data. In this manuscript, the focus was put on the quantitative findings, including participation numbers and registrations, interaction behaviour (chat and Q&A messages), live poll engagement, YouTube view counts, submitted learning journals, and issued certificates of achievement or participation.

The high number of registrations and consistently strong attendance throughout the semester highlight the substantial public interest in the topic of human–animal relationships. YouTube view counts further suggest sustained interest beyond the live events, as well as potential sharing or recommendation of the recordings. Interaction rates—particularly chat and Q&A messages and poll responses—were strikingly high in the first few sessions, indicating initial enthusiasm and the effectiveness of interactive, activating elements in digital teaching formats [

43]. Over time, however, a gradual decline in interaction was observed, which may reflect the onset of “video conferencing fatigue” [

44,

45]. Video conferencing fatigue refers to the cumulative cognitive load inherent to synchronous online communication, arising from intensified self-presentation demands, limited nonverbal feedback, and sustained attentional effort [

46,

47]. Evidence suggests that fatigue can be mitigated through interface and format adjustments—such as disabling self-view, fostering active participation, and optimizing visual settings [

45]—as well as through practical measures including micro-breaks, shorter meeting segments, and alternating synchronous and asynchronous tasks [

48]. Content analysis further suggests that emotionally and ethically charged topics such as animal ethics, hunting, or animal transport generated particularly strong participant engagement. The higher number of learning journals submitted in response to these topics also points to more intense individual reflection.

The findings demonstrate that the lecture series served as an accessible and effective format for communicating complex and transdisciplinary topics such as the human–animal relationship. The combination of expert lectures, emotionally engaging elements (e.g., film screening), peer contributions, and the concluding Barcamp appeared to strengthen participants’ identification with the content and fostered active engagement [

49]. Furthermore, transformative learning formats emphasize the importance of fostering group responsibility, individual agency, and the interplay between critical reflection and affective learning. These approaches support the development of personal and social awareness, which in turn enhances the relevance and depth of course content [

50,

51]. The lecture series challenged participants across multiple dimensions—emotional, ethical, and academic—and thus created meaningful opportunities for transformative learning.

The lecture series contributed to a broader reflection on contemporary human–animal relationships. Its interdisciplinary approach demonstrated how our understanding of human–animal-relationships is shaped not only by biological and ecological knowledge, but also by cultural narratives, moral frameworks, and sociopolitical contexts. Within the paradigms of “One Health” and “Planetary Health,” animals appear as cohabitants, sentient beings, and indicators of environmental change. The pluralistic content of the lecture series challenges anthropocentric assumptions and invites participants to reconsider their relational responsibility toward nonhuman life. To investigate this further, a pre–post survey on the attendees’ views on human–animal-relationships was conducted, which will be presented in a subsequent paper.

Empirical studies on education about human–animal relations support this approach. Hawkins et al. [

52] demonstrate that educational formats can foster more positive attitudes toward human–animal relationships. This aligns with the patterns observed in the present lecture series. The high participation numbers and intensive interaction indicate increased engagement and reflective involvement, which may be associated with shifts in perspective. This connects to the argument made by Feltz et al. [

53], who show that educational interventions can increase knowledge about animals in food production and reduce speciesist justifications, even if such changes do not immediately translate into behavioral modification. The pronounced interaction of participants, especially during ethically and conceptually complex sessions, supports this pattern and suggests that learning processes may manifest primarily through discursive and reflective engagement rather than through immediately observable behavior. As in many studies, including the present one, researchers often rely on indirect indicators of learning, highlighting the need for future study designs that capture attitudinal and behavioral change more systematically and over longer periods of time.

This approach is particularly relevant for conveying other societally important and interdisciplinary topics. The 21st century is marked by complex global challenges that require transdisciplinary solutions [

54]. Climate change, for example, was a recurring topic in the lecture series, particularly its link to industrial animal use. Within the health sector, the consequences are already apparent: extreme heat events and food insecurity are placing increased strain on healthcare systems. According to the WHO, an average of 489,000 heat-related deaths per year occurred between 2000 and 2019, with vulnerable groups such as women, older adults, and individuals with chronic illnesses disproportionately affected [

55,

56]. In parallel, climate change impairs agricultural productivity, nutrient bioavailability, and pest resistance, thereby weakening public health outcomes in the long run [

57].

A large proportion of lecture participants were affiliated with health professions—an important group in addressing these challenges, both in their clinical expertise and their role as trusted figures and change agents. Rossa-Roccor et al. [

58] advocate for a greater commitment from health professionals to drive political change by framing climate change as a health issue. However, current knowledge about climate-related health impacts remains limited among healthcare workers [

59]. This underscores the need for broad, interdisciplinary educational formats, particularly for students in health-related fields, to help shape a more sustainable future and to promote both individual and systemic change. Together, interaction metrics (chat, Q&A, polls, Barcamp) and reflective-journal submissions indicate active engagement with human–animal relationship topics. Where affiliation data were available, we observed substantive participation by individuals from health-related fields, supporting our hypotheses that professionals outside animal-focused disciplines can be engaged by this format.

Another domain that would benefit from such educational formats includes politically charged and health-related issues such as wars, authoritarianism, and the resurgence of nationalism, all of which hinder global cooperation [

60]. Access to healthcare is increasingly limited in many parts of the world, while rising inequality, mental health burdens, and fragile living conditions call for adaptable und accessible healthcare systems [

61,

62]. Climate-induced migration further intensifies these public health challenges [

63].

Digital transformation also presents new opportunities for promoting sustainability and interprofessional learning through transformative educational formats [

64]. The health professions are especially impacted by these shifts and must be adequately prepared for the increasing digitization of the working world. Digitization holds great potential, for example, in saving resources [

65], facilitating interprofessional exchange, and enhancing patient empowerment through improved access to information and communication [

66]. At the same time, there is a risk that digital health innovations may exacerbate social inequalities. Individuals with lower income, limited education, or poor digital literacy are less likely to benefit from these developments [

67,

68].

The demand for interdisciplinary education is therefore broad and multifaceted—essential not only for society but also for preparing future professionals to navigate ethical complexity and real-world challenges. When embedded systematically into curricula, such formats foster improved collaboration, communication skills, and mutual role understanding among learners from different disciplines [

69]. The most lasting effects are observed when interdisciplinary learning is integrated longitudinally throughout a program of study, strengthening cross-cutting competencies and building a foundation for effective cooperation in complex professional settings [

70,

71].

4.1. Limitations

Despite the positive reception of the lecture series, several methodological and structural limitations must be considered. The interactive tools used during the course—such as live polls and the Barcamp workshop—were not systematically assessed in terms of their specific didactic impact; future iterations of the lecture series would benefit from a more nuanced analysis of their usage and educational effectiveness.

Additionally, it should be noted that the particularly high attendance during the first session may be partly attributed to its role as an introductory event, during which organizational details as well as requirements for certificates of achievement and of participation were outlined.

Although a self-selection bias cannot be entirely ruled out due to the voluntary nature of participation, the large sample size and the heterogeneity of participants mitigate this concern. The cohort included individuals motivated by the thematic focus as well as those primarily interested in the digital format, resulting in a balanced mixture of perspectives. In contrast to our earlier small-scale seminar with 30 students, the registration of more than 1300 participants substantially reduces the likelihood that individual predispositions substantially influenced the overall findings.

Technical limitations of the Zoom platform—such as the restricted functionality for group work in webinar mode—should also be taken into account when planning similar formats in the future.

4.2. Outlook

The results of the evaluation highlight the strong potential of the Human–Animal Relationship lecture series as an innovative educational model. Integrating similar formats into mandatory components of academic programs, particularly in the context of Planetary Health or One Health, appears beneficial to promote sustainability-oriented and ethically grounded thinking early in students’ education. Beyond curricular integration, the event also offers opportunities to strengthen its citizen science dimension. Research has shown that involving participants in data collection and evaluation not only enhances environmental awareness and scientific literacy but also increases engagement and motivation in academic settings [

72]. Greater inclusion of civil society actors—for example through collaborative projects or open-access platforms—could extend the impact of the lecture series beyond academia and contribute to social innovation [

73].

Additionally, the internationalization of the format represents a promising next step. Collaborations with other universities, non-governmental institutions, or international institutions could help globalize and diversify the discourse on human–animal relationships. The scalability and repeatability of the lecture series should also be assessed to further its reach and impact.

A planned qualitative and quantitative analysis of questionnaire data collected before and after the course will be presented in a second paper. These findings are expected to provide further insights into participants’ knowledge acquisition and changes in attitudes, forming a foundation for the continued development and didactic refinement of the format.