Advancing Wildlife Conservation Through Biobanking in South America

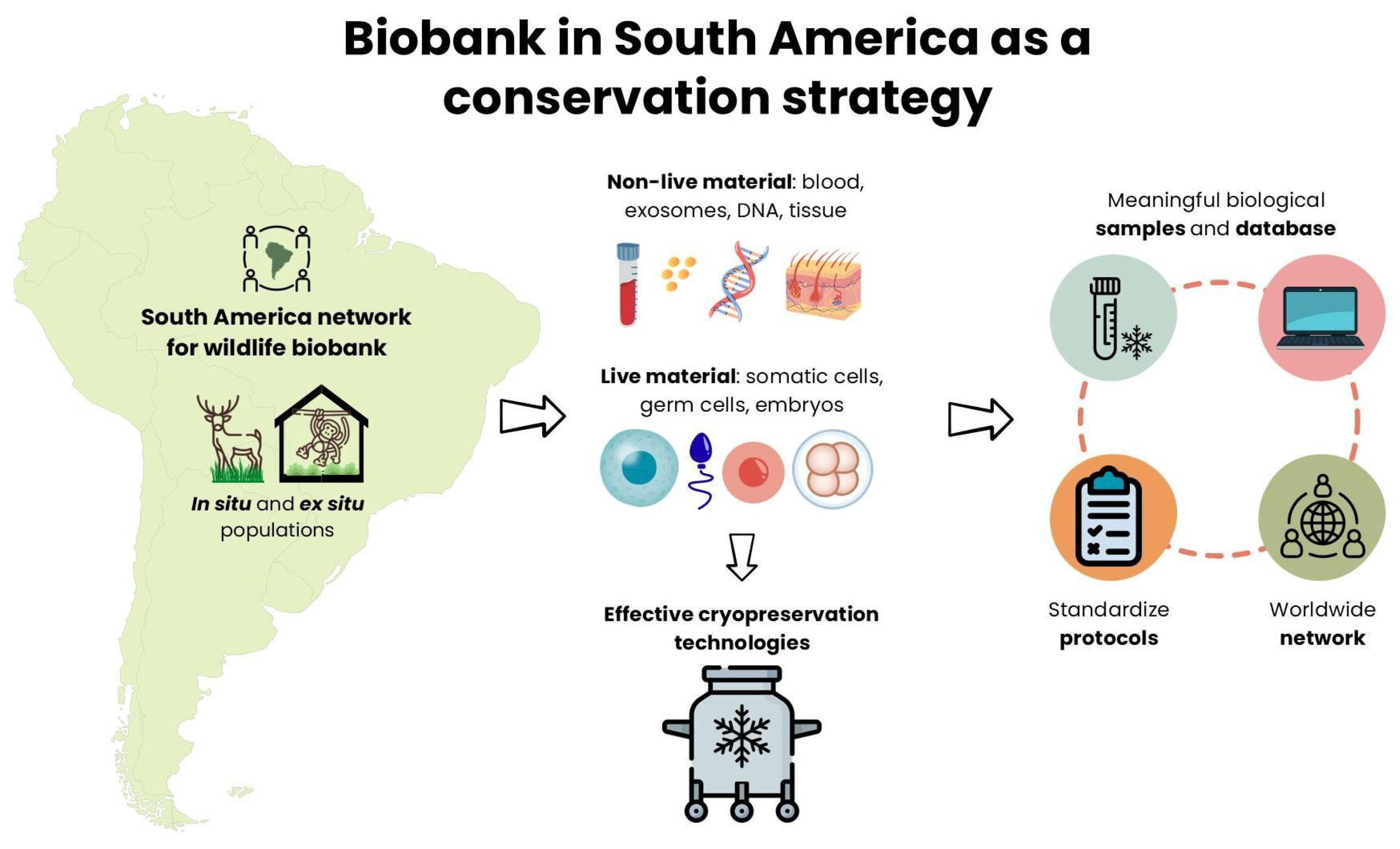

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Challenges in Establishing Biobanks for Conservation in South America

3. Opportunities

4. The Future of Biobanking in South America

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ceballos, G.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Barnosky, A.D.; García, A.; Pringle, R.M.; Palmer, T.M. Accelerated modern human-induced species losses: Entering the sixth mass extinction. Sci. Adv. 2015, 19, e1400253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; Version 2022-2; International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources: Gland, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Prentice, J.R.; Anzar, M. Cryopreservation of mammalian oocyte for conservation of animal genetics. Vet. Med. Int. 2010, 2011, 146405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolton, R.L.; Mooney, A.; Pettit, M.T.; Bolton, A.E.; Morgan, L.; Drake, G.J.; Appeltant, R.; Walker, S.L.; Gillis, J.D.; Hvilsom, C. Resurrecting biodiversity: Advanced assisted reproductive technologies and biobanking. Reprod. Fertil. 2022, 3, R121–R146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, R.J.; O’Brien, J.K.; Spindler, R.E. Strategic gene banking for conservation: The ins and outs of a living bank. In Scientific Foundations of Zoos and Aquariums, 1st ed.; Kaufman, A.B., Bashaw, M.J., Maple, T.L., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 112–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, R.; Watson, P. Defining biobank. Biopreservation Biobank 2013, 11, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strand, J. Biobanking in amphibian and reptilian conservation and management: Opportunities and challenges. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2020, 12, 709–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon-Quinto, T.; Simon, M.A.; Cadenas, R.; Jones, J.; Martinez-Hernandez, F.J.; Moreno, J.M.; Vargas, A.; Martinez, F.; Soria, B. Developing biological resource banks as a supporting tool for wildlife reproduction and conservation The Iberian lynx bank as a model for other endangered species. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2009, 112, 347–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Liu, J.; Holland, M.K.; Temple-Smith, P.; Williamson, M.; Verma, P.J. Nanog is an essential factor for induction of pluripotency in somatic cells from endangered felids. Biores. Open Access 2013, 2, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodoro, L.O.; Camargo, L.S.; Scheeren, V.F.C.; Freitas-Dell’Aqua, C.P.; Papa, F.O.; Honsho, C.S.; Souza, F.F. First successful frozen semen of the maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus). Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2021, 56, 1464–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, C.; Clavijo, C.; Rojas-Bonzi, V.; Miño, C.I.; González-Maya, J.F.; Bou, N.; Giraldo, A.; Martino, A.; Miyaki, C.Y.; Aguirre, L.F.; et al. Understanding the conservation-genetics gap in Latin America: Challenges and opportunities to integrate genetics into conservation practices. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1425531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rola, L.D.; Buzanskas, M.E.; Melo, L.M.; Chaves, M.S.; Freitas, V.J.F.; Duarte, J.M.B. Assisted reproductive technology in neotropical deer: A model approach to preserving genetic diversity. Animals 2021, 11, 1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espejo, C.; Ezenwa, V.O. Extracellular vesicles: An emerging tool for wild immunology. Discov. Immunoly 2024, 3, kyae011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comizzoli, P.; Power, M. Reproductive microbiomes in wild animal species: A new dimension in conservation biology. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1200, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallas, J.W.; Warne, R.W. Captivity and animal microbiomes: Potential roles of microbiota for influencing animal conservation. Microb. Ecol. 2023, 85, 820–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, C.M.; Oliveira, V.C.; Paraventi, M.D.; Cardoso, R.N.R.; Martins, D.S.; Ambrósio, C.E. Maintenance of Brazilian Biodiversity by germplasm bank. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2016, 36, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasetti, P.; Mercugliano, E.; Schrade, L.; Spiriti, M.M.; Goritz, F.; Holtze, S.; Seet, S.; Galli, C.; Stejskal, J.; Colleoni, S.; et al. Ethical assessment of genome resource banking (GRB) in wildlife conservation. Cryobiology 2024, 117, 104956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baust, J.M.; Corwin, W.L.; VanBuskirk, R.; Baust, J.G. Biobanking in the 21st century. In Revue Francaise de Psychanalyse, 1st ed.; Karimi-Busheri, F., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 65. [Google Scholar]

- Clulow, J.; Clulow, S. Cryopreservation and other assisted reproductive technologies for the conservation of threatened amphibians and reptiles: Bringing the ARTs up to speed. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2016, 28, 1116–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Bruford, M.W. The Frozen Ark Project—Biobanking endangered animal samples for conservation and research. Inside Ecol. Mag. 2018, 2, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.M.; Mastromonaco, G.F. The evolution of conservation biobanking: A literature review and analysis of terminology, taxa, location, and strategy of wildlife biobanks over time. Biopreservation Biobank 2025, 23, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brereton, J.E.; Spooner, S.L.; Walker, S.L.; Mooney, A.; Wilson, P.; Mastromonaco, G.F.; Hunter, E.; White, S. When to cryopreserve and when to let it go? A systematic review of priorities in wild animal cryobanking. Theriogenology Wild 2025, 6, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, A.; Ryder, O.A.; Houck, M.L.; Staerk, J.; Conde, D.A.; Buckley, Y.M. Maximizing the potential for living cell banks to contribute to global conservation priorities. Zoo Biol. 2023, 42, 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.D.C.B.; Aquino, L.V.C.; Nascimento, M.B.; Silva, M.B.; Rodrigues, L.L.V.; Praxedes, E.A.; Oliveira, L.R.M.; Silva, H.V.R.; Nunes, T.G.P.; Oliveira, M.F.; et al. Evaluation of different skin regions derived from a postmortem jaguar, Panthera onca (Linnaeus, 1758), after vitrification for development of cryobanks from captive animals. Zoo Biol. 2021, 40, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praxedes, É.A.; Oliveira, L.R.M.; Silva, M.B.; Borges, A.A.; Santos, M.V.O.; Silva, H.V.R.; Pereira, A.F. Effects of cryopreservation techniques on the preservation of ear skin–An alternative approach to conservation of jaguar, Panthera onca (Linnaeus, 1758). Cryobiology 2019, 88, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queiroz Neta, L.B.; Lira, G.P.O.; Borges, A.A.; Santos, M.V.O.; Silva, M.B.; Oliveira, L.R.M.; Silva, A.R.; Oliveira, M.F.; Pereira, A.F. Influence of storage time and nutrient medium on recovery of fibroblast-like cells from refrigerated collared peccary (Pecari tajacu Linnaeus, 1758) skin. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 2018, 5, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Gac, S.; Ferraz, M.; Venzac, B.; Comizzoli, P. Understanding and assisting reproduction in wildlife species using microfluidics. Trends Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 584–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.M.; Pereira, A.F.; Comizzoli, P.; Silva, A.R. Cryopreservation and culture of testicular tissues: An essential tool for biodiversity preservation. Biopreservation Biobank 2020, 18, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naranjo, R.E.; Naydenova, E.; Proaño-Bolaños, C.; Vizuete, K.; Debut, A.; Arias, M.T.; Coloma, L.A. Development of assisted reproductive technologies for the conservation of Atelopus sp. (spumarius complex). Cryobiology 2022, 105, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péricard, L.; Mével, S.L.; Marquis, O.; Locatelli, Y.; Coen, L. Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection Using 20-Year-Old Cryopreserved sperm results in normal, viable, and reproductive offspring in Xenopus laevis: A major pioneering achievement for amphibian conservation. Animals 2025, 15, 1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastromonaco, G. 40 ‘wild’ years: The current reality and future potential of assisted reproductive technologies in wildlife species. Anim. Reprod. 2024, 21, e20240049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benham, H.M.; McCollum, M.P.; Nol, P.; Frey, R.K.; Clarke, P.R.; Rhyan, J.C.; Barfield, J.P. Production of embryos and a live offspring using postmortem reproductive material from bison (Bison bison bison) originating in Yellowstone National Park, USA. Theriogenology 2021, 160, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrick, J.R.; Bartels, P.; Krisher, R.L. Postthaw evaluation of in vitro function of epididymal spermatozoa from four species of free-ranging African bovids. Biol. Reprod. 2004, 71, 948–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meintjes, M.; Bezuidenhout, C.; Bartels, P.; Visser, D.S.; Loskutoff, N.M.; Fourie, F.L.R.; Barry, D.M.; Godke, R.A. In Vitro maturation and fertilization of oocytes recovered from free-ranging Burchell’s zebra (Equus burchelli) and Hartmann’s zebra (Equus zebra hartmannae). J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 1997, 28, 251–259. [Google Scholar]

- Souza, L.S.B.; Polizelle, S.R.; Olindo, S.L.; Silva, M.C.C.; Vieria, G.C.; Acacio, B.R.; Navarezi, I.F.; Chagas, M.G.; Silva, N.C.; Jorge Neto, P.N.; et al. Xenotransplante de tecido somático de onça-pintada (Panthera onca) em camundongos NSG: Uma alternativa para obtenção de fibroblastos de animais mortos por atropelamento. Rev. Bras. Reprod. Anim. 2023, 47, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Paskal, W.; Paskal, A.M.; Dębski, T.; Gryziak, M.; Jaworowski, J. Aspects of Modern Biobank Activity—Comprehensive Review. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2018, 24, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artene, S.; Ciurea, M.E.; Purcaru, S.O.; Tache, D.T.; Tataranu, L.G.; Lupu, M.; Dricu, A. Biobanking in a constantly developing medical world. Sci. World J. 2013, 23, 343275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Späth, M.B.; Grimson, J. Applying the archetype approach to the database of a biobank information management system. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2011, 80, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zika, E.; Paci, D.; Braun, A.; Rijkers-Defrasne, S.; Deschênes, M.; Fortier, I.; Laage-Hellman, J.; Scerri, C.A.; Ibarreta, D. A European survey on biobanks: Trends and issues. Public Health Genom. 2011, 14, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, G.; Boettcher, P.; Besbes, B.; Danchin-Burge, C.; Baumung, R.; Hiemstra, S.J. Cryoconservation of Animal Genetic Resources in Europe and Two African Countries: A Gap Analysis. Diversity 2019, 11, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praxedes, É.A.; Queiroz Neta, L.B.; Borges, A.A.; Silva, M.B.; Santos, M.V.O.; Ribeiro, L.R.; Pereira, A.F. Quantitative and descriptive histological aspects of jaguar (Panthera onca Linnaeus, 1758) ear skin as a step towards formation of biobanks. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 2020, 49, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eiseman, E.; Bloom, G.; Brower, J.; Clancy, N.; Olmsted, S.S. Case Studies of Existing Human Tissue Repositories: “Best Practices” for a Biospecimen Resource for the Genomic and Proteomic Era; RAND Corporation: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2003; p. 246. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7249/mg120ndc-nci (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Fujihara, M.; Comizzoli, P. Human and wildlife biobanks of germplasms and reproductive tissues can contribute to a broader concept of One Health. FS Rep. 2025, 6, 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madelaire, C.B.; Klink, A.C.; Israelsen, W.J.; Hindle, A.G. Fibroblasts as an experimental model system for the study of comparative physiology. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2022, 260, 110735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, A.M.; Appeltant, R.; Burdon, T.; Bao, Q.; Bargaje, R.; Bodnar, A.; Chambers, S.; Comizzoli, P.; Cook, L.; Endo, Y.; et al. Advancing stem cell technologies for conservation of wildlife biodiversity. Development 2024, 151, 203116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimkus, B.M.; Hassapakis, C.L.; Houck, M.L. Integrating current methods for the preservation of amphibian genetic resources and viable tissues to achieve best practices for species conservation. Amphib. Reptile Conserv. 2018, 12, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Comizzoli, P.; Wildt, D.E. Cryobanking Biomaterials from Wild Animal Species to Conserve Genes and Biodiversity: Relevance to Human Biobanking and Biomedical Research. In Biobanking of Human Biospecimens; Hainaut, P., Vaught, J., Zatloukal, K., Pasterk, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.; Vaught, J.; Tulskie, B.; Olson, D.; Odeh, H.; McLean, J.; Moore, H.M. Critical financial challenges for biobanking: Report of a National Cancer Institute Study. Biopreservation Biobank 2019, 17, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.S.; Garrido, N.L.B.; Lord, G.; Maggio, Z.A.; Khomtchouk, B.B. Ethical considerations for biobanks serving underrepresented populations. Biotechics 2025, 39, 240–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parry-Jones, A. Enhancing quality biobanking through education. Cryobiology 2022, 109, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, W.V. Biobanks, offspring fitness and the influence of developmental plasticity in conservation biology. Anim. Reprod. 2023, 28, e20230026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Mal, G.; Gautam, S.K.; Mukesh, M. Biotechnology for Wildlife. Adv. Anim. Biotech. 2019, 6, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, C.R.R. The Golden lion tamarin Leontopithecus rosalia: A conservation success story. Int. Zoo Yearb. 2012, 46, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arakaki, P.R.; Salgado, P.A.B.; Losano, J.D.D.A.; Gonçalves, D.R.; Valle, R.D.R.D.; Pereira, R.J.G.; Nichi, M. Semen cryopreservation in golden-headed lion tamarin, Leontopithecus chrysomelas. Am. J. Primatol. 2019, 81, e23071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aliaga-Samanez, G.G.; Javarotti, N.B.; Orecife, G.; Chávez-Congrains, K.; Pissinatti, A.; Monticelli, C.; Cristina Marques, M.; Galbusera, P.; Galetti, P.M., Jr.; Domingues de Freitas, P. Genetic diversity in ex situ populations of the endangered Leontopithecus chrysomelas and implications for its conservation. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0288097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gañán, R.; González, A.S.; Garde, J.J.; Sánchez, I.; Aguilar, J.M.; Gomendio, M.; Roldan, E.R.S. Male reproductive traits, semen cryopreservation, and heterologous in vitro fertilization in the bobcat (Lynx rufus). Theriogenology 2009, 72, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saragusty, J.; Anzalone, D.A.; Palazzese, L.; Arav, A.; Patrizio, P.; Gosálvez, J.; Loi, P. Dry biobanking as a conservation tool in the Anthropocene. Theriogenology 2020, 150, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, L.G.; Johnston, S.D.; O’Brien, J.K.; Frankham, R.; Rodger, J.C.; Ryan, S.A.; Beranek, C.T.; Clulow, J.; Hudson, D.S.; Witt, R.R. Modelling genetic benefits and financial costs of integrating biobanking into the captive management of koalas. Animals 2022, 12, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, L.G.; Mawson, P.R.; Comizzoli, P.; Witt, R.R.; Frankham, R.; Clulow, S.; O’Brien, J.K.; Clulow, J.; Marinari, P.; Rodger, J.C. Modeling genetic benefits and financial costs of integrating biobanking into the conservation breeding of managed marsupials. Conserv. Biol. 2023, 37, e14010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caenazzo, L.; Tozzo, P. The Future of Biobanking: What Is Next? BioTech 2020, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vazquez, J.M.; Khudyakov, J.I.; Madelaire, C.B.; Godard-Codding, C.A.; Routti, H.; Lam, E.; Piotrowski, E.; Merrill, G.; Wisse, J.; Allen, K.; et al. Ex vivo and in vitro methods as a platform for studying anthropogenic effects on marine mammals: Four challenges and how to meet them. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 11, 1466968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, L.G.; Frankham, R.; Rodger, J.C.; Witt, R.R.; Clulow, S.; Upton, R.M.; Clulow, J. Integrating biobanking minimises inbreeding and produces significant cost benefits for a threatened frog captive breeding programme. Conserv. Lett. 2021, 14, e12776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Type | Definition | Live or Non-Living | Preservation Temperature | Possible Application | Examples of Conservation Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somatic cell | Diploid cells (e.g., fibroblasts) | Live | Liquid nitrogen (−196 °C) | Experimental cell physiology | Jaguar (Panthera onca) fibroblasts induced to pluripotent stage | [9] |

| Germ cells | Reproductive cells (e.g., sperm, oocytes) | Live | Liquid nitrogen (−196 °C) | Assisted Reproduction | Cryopreservation of maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus) sperm | [10] |

| Tissues, blood, and cell pellet | Aliquots of organs, blood, non-live cells | Non-living | Freezer (−80 °C) | Genomic sequencing | Several species | [11] |

| Embryos | Early-stage development of multicellular organisms produced by IVF or cloning | Live | Liquid nitrogen (−196 °C) | Assisted Reproduction | Neotropical deer species | [12] |

| Exosomes | Messager particles released by cells | Non-living | Freezer (−80 °C) | Therapeutic application | Several species | [13] |

| Microbiomes | Associated micro-organisms (bacteria, fungi, viruses) | Live | Liquid nitrogen (−196 °C)/Freezer (−80 °C) | Conservation and restoration of the adaptive capacity of a species to its environment | General | [14,15] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Madelaire, C.B.; Pereira, A.F.; Sestelo, A.J.; Bom-Conselho, A.P.; Vaj, C.; Mosalve, F.C.; Brandão-Souza, L.S.; Tavares, M.R.; Rodriguez, M.D.; Restrepo, R.O.; et al. Advancing Wildlife Conservation Through Biobanking in South America. Animals 2025, 15, 3261. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223261

Madelaire CB, Pereira AF, Sestelo AJ, Bom-Conselho AP, Vaj C, Mosalve FC, Brandão-Souza LS, Tavares MR, Rodriguez MD, Restrepo RO, et al. Advancing Wildlife Conservation Through Biobanking in South America. Animals. 2025; 15(22):3261. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223261

Chicago/Turabian StyleMadelaire, Carla B., Alexsandra F. Pereira, Adrián J. Sestelo, Aléxia P. Bom-Conselho, Carolina Vaj, Felipe C. Mosalve, Larissa S. Brandão-Souza, Marcela R. Tavares, Matteo Duque Rodriguez, Raquel O. Restrepo, and et al. 2025. "Advancing Wildlife Conservation Through Biobanking in South America" Animals 15, no. 22: 3261. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223261

APA StyleMadelaire, C. B., Pereira, A. F., Sestelo, A. J., Bom-Conselho, A. P., Vaj, C., Mosalve, F. C., Brandão-Souza, L. S., Tavares, M. R., Rodriguez, M. D., Restrepo, R. O., Leite, R. F., Locatelli, Y., Deco-Souza, T., & Araujo, G. R. d. (2025). Advancing Wildlife Conservation Through Biobanking in South America. Animals, 15(22), 3261. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223261