Acoustic Identity: Linking Signature Whistles and Visual Identification in a Threatened Dolphin Population

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Signature Whistles

1.2. Burrunan Dolphin

1.3. Rationale and Study Aim

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fieldwork

2.1.1. Study Site

2.1.2. Data Collection

2.2. Data Preparation

2.2.1. Photo-Identification

2.2.2. SW Identification and Extraction

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sighting Associations

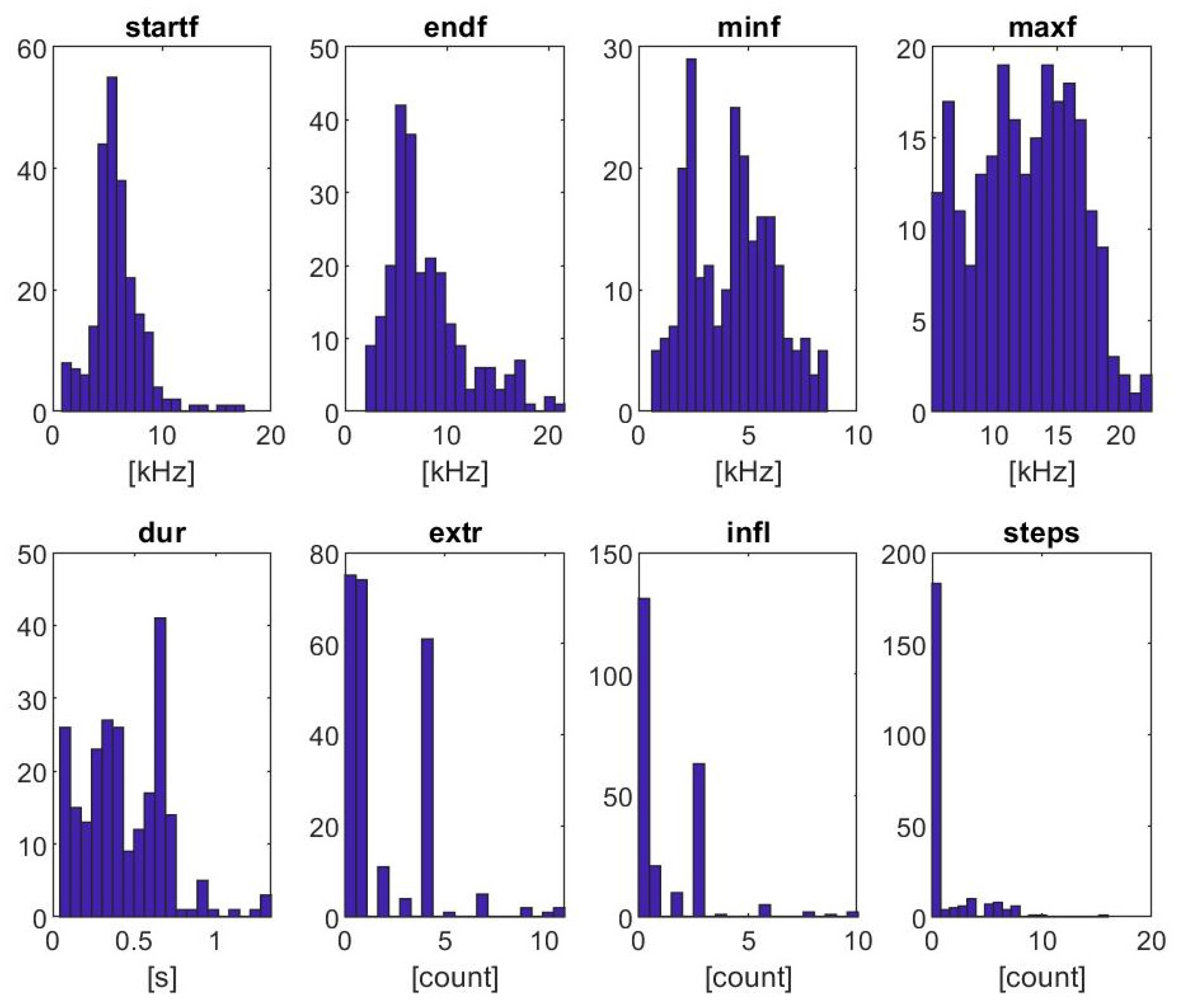

3.2. Signature Whistle Contours

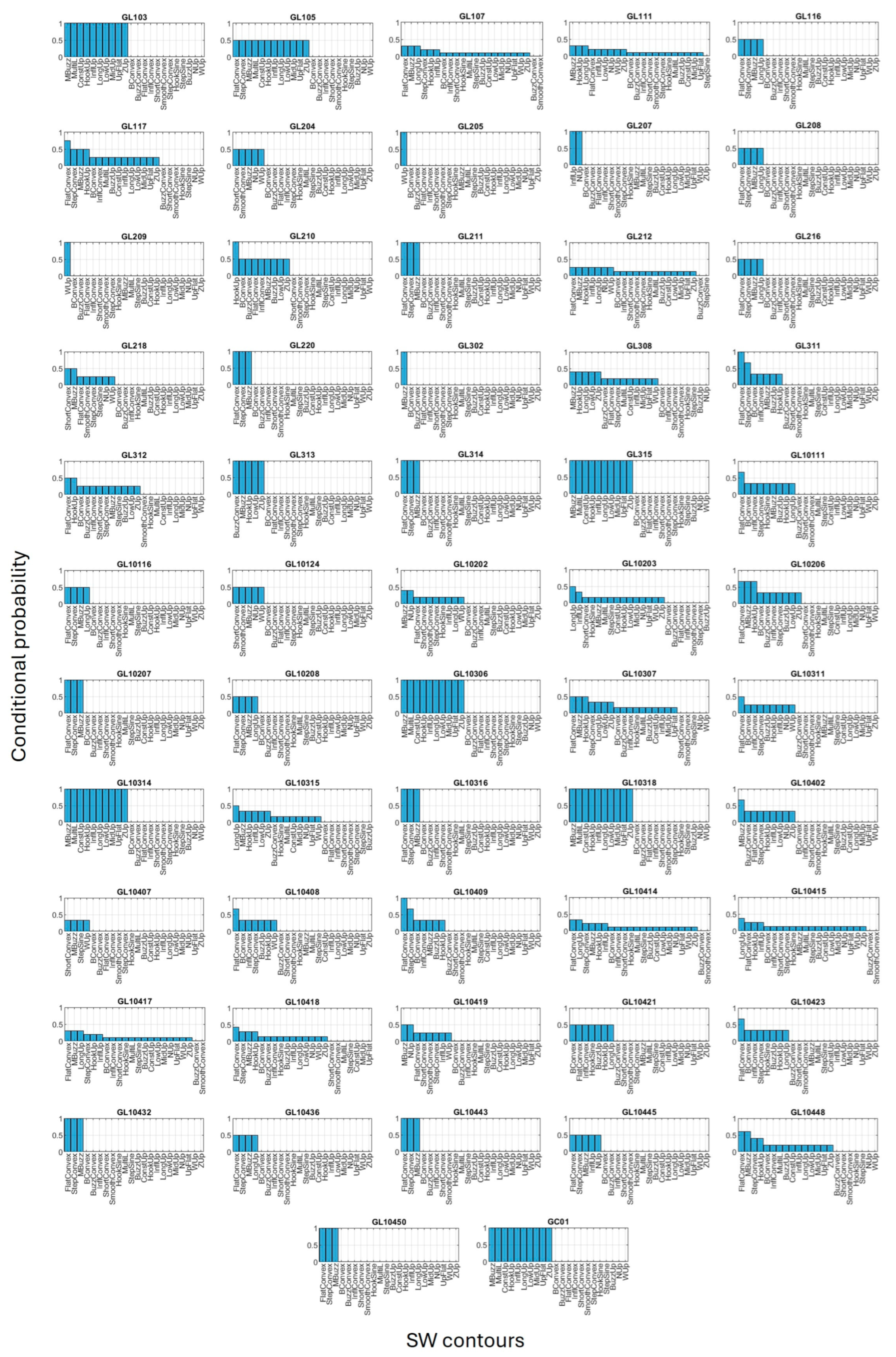

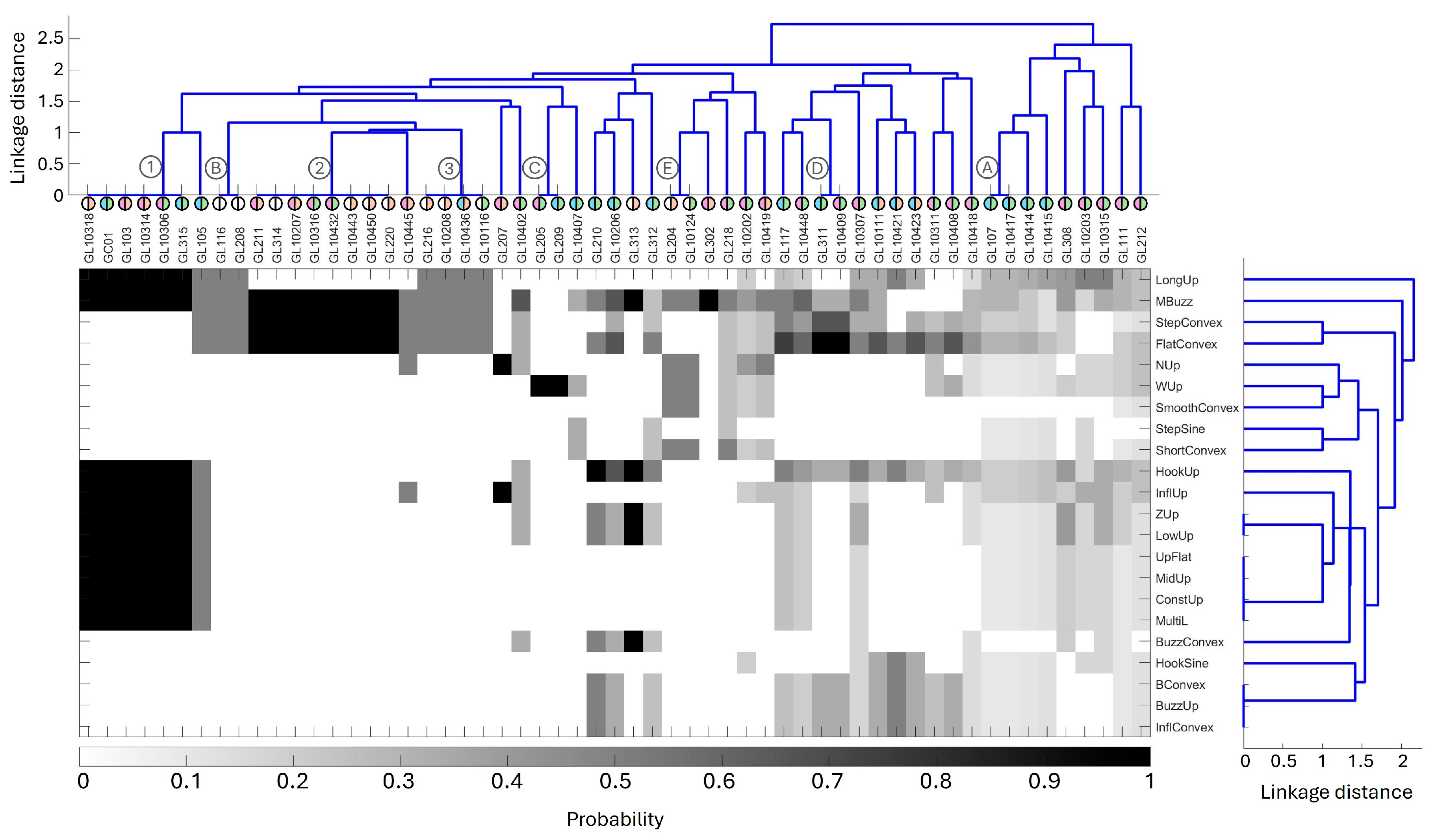

3.3. Conditional Probability

3.4. Clustering Contours and Individuals

4. Discussion

4.1. Fission–Fusion

4.2. Male–Female

4.3. Resident–Transient

4.4. SW in PAM

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jones, B.; Zapetis, M.; Samuelson, M.; Ridgway, S. Sounds produced by bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops): A review of the defining characteristics and acoustic criteria of the dolphin vocal repertoire. Bioacoustics 2020, 29, 399–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D. Whistles of bottlenose dolphins: Comparisons among populations. Aquat. Mamm. 1995, 21, 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- Herzing, D. Clicks, whistles and pulses: Passive and active signal use in dolphin communication. Acta Astronaut. 2014, 105, 534–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janik, V.M.; Todt, D.; Dehnhardt, G. Signature whistle variations in a bottlenosed dolphin, Tursiops truncatus. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1994, 35, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, M.C.; Caldwell, D.K. Vocalization of naive captive dolphins in small groups. Science 1968, 159, 1121–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janik, V.M.; Sayigh, L.S. Communication in bottlenose dolphins: 50 years of signature whistle research. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2013, 199, 479–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sportelli, J.J.; Jones, B.L.; Ridgway, S.H. Non-linear phenomena: A common acoustic feature of bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) signature whistles. Bioacoustics 2023, 32, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayigh, L.; Esch, H.; Wells, R.; Janik, V. Facts about signature whistles of bottlenose dolpins, Tursiops truncatus. Anim. Behav. 2007, 74, 1631–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovsyanikova, E.; McGovern, B.; Hawkins, E.; Huijser, L.; Dunlop, R.; Noad, M. Balance between stability and variability in bottlenose dolphin signature whistles offers potential for additional information. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2025, 157, 2982–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolker, R.A.; Mann, J.; Smuts, B.B. Use of signature whistles during separations and reunions by wild bottlenose dolphin mothers and infants. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1993, 33, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayigh, L.S.; El Haddad, N.; Tyack, P.L.; Janik, V.M.; Wells, R.S.; Jensen, F.H. Bottlenose dolphin mothers modify signature whistles in the presence of their own calves. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2300262120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayigh, L.S.; Tyack, P.L.; Wells, R.S.; Scott, M.D. Signature whistles of free-ranging bottlenose dolphins Tursiops truncatus: Stability and mother-offspring comparisons. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1990, 26, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, L.M. Sociogenetic structure, kin associations and bonding in delphinids. Mol. Ecol. 2012, 21, 745–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gowans, S.; Würsig, B.; Karczmarski, L. The social structure and strategies of delphinids: Predictions based on an ecological framework. In Advances in Marine Biology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007; Volume 53, pp. 195–294. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, R.C.; Cioffi, W.R.; Randić, S.; Allen, S.J.; Watson-Capps, J.; Krützen, M. Male alliance behaviour and mating access varies with habitat in a dolphin social network. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiszniewski, J.; Brown, C.; Möller, L.M. Complex patterns of male alliance formation in a dolphin social network. J. Mammal. 2012, 93, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janik, V.M.; King, S.L.; Sayigh, L.S.; Wells, R.S. Identifying signature whistles from recordings of groups of unrestrained bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). Mar. Mammal Sci. 2013, 29, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, M.; Berggren, P. A comparison of photo-ID and signature whistle based capture-recapture abundance estimates of common bottlenose dolphin. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2024, 41, e13218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearey, J.; Elwen, S.; James, B.; Gridley, T. Identification of potential signature whistles from free-ranging common dolphins (Delphinus delphis) in South Africa. Anim. Cogn. 2019, 22, 777–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, C.L.; Gowans, S.; Simard, P. Identifying and characterizing signature whistles using photo-identification of free-ranging bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in Tampa Bay, Florida. Aquat. Mamm. 2025, 51, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serres, A.; Thomas, J.-H.; Dong, L.; Chen, S.; Liu, B.; Li, S. Potential signature whistle production by Indo-Pacific humpback dolphins, Sousa chinensis, in the northern South China sea. Anim. Behav. 2024, 218, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeu, B.; Daura-Jorge, F.G.; Hammond, P.S.; Castilho, P.V.; Simões-Lopes, P.C. Assessing spatial patterns and density of a dolphin population through signature whistles. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2024, 40, 222–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton-Robb, K.; Gershwin, L.; Thompson, R.; Austin, J.; Owen, K.; McKechnie, S. A new dolphin species, the Burrunan Dolphin Tursiops australis sp. nov., endemic to southern Australian coastal waters. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, K.; Charlton-Robb, K.; Thompson, R. Resolving the trophic relations of cryptic species: An example using stable isotope analysis of dolphin teeth. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passadore, C.; Parra, G.J.; Moller, L. Unravelling the secrets of a new dolphin species: Population size and spatial ecology of the Burrunan dolphin (‘Tursiops australis’) in Coffin Bay, South Australia. South Aust. Nat. 2015, 89, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Charlton-Robb, K.; Taylor, A.; McKechnie, S. Population genetic structure of the Burrunan dolphin (Tursiops australis) in coastal waters of south-eastern Australia: Conservation implications. Conserv. Genet. 2015, 16, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beddoe, J.; Shimeta, J.; Klaassen, M.; Robb, K. Population distribution and drivers of habitat use for the Burrunan dolphins, Port Phillip Bay, Australia. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e11221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puszka, H.; Shimeta, J.; Robb, K. Assessment on the effectiveness of vessel-approach regulations to protect cetaceans in Australia: A review on behavioral impacts with case study on the threatened Burrunan dolphin (Tursiops australis). PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0243353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foord, C.; Szabo, D.; Robb, K.; Clarke, B.; Nugegoda, D. Hepatic concentrations of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in dolphins from south-east Australia: Highest reported globally. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 908, 168438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monk, A.; Charlton-Robb, K.; Buddhadasa, S.; Thompson, R.M. Comparison of mercury contamination in live and dead dolphins from a newly described species, Tursiops australis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon, P.; Raulings, E.; Roach, M.; Morris, K. Vegetation changes over a four decade period in Dowd Morass, a brackish-water wetland of the Gippsland Lakes, South-Eastern Australia. Proc. R. Soc. Vic. 2008, 120, 403–418. [Google Scholar]

- Foord, C.S.; Robb, K.; Nugegoda, D. Legacy organic pollutants are still a threat for resident dolphins of south-east Australia. Environ. Res. 2025, 270, 121045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foord, C.S.; Robb, K.; Nugegoda, D. Trace element concentrations in dolphins of south-east Australia; mercury a cause for concern in the region. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 209, 117130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duignan, P.; Stephens, N.; Robb, K. Fresh water skin disease in dolphins: A case definition based on pathology and environmental factors in Australia. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, R.; Krützen, M. Male dolphin alliances in Shark Bay: Changing perspectives in a 30-year study. Anim. Behav. 2015, 103, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, Q.A.; Mann, J. The size, composition and function of wild bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops sp.) mother–calf groups in Shark Bay, Australia. Anim. Behav. 2008, 76, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabanne, D.B.H.; Krützen, M.; Finn, H.; Allen, S.J. Evidence of male alliance formation in a small dolphin community. Mamm. Biol. 2022, 102, 1285–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermak, J.; Brightwell, K.; Gibson, Q. Multi-level dolphin alliances in northeastern Florida offer comparative insight into pressures shaping alliance formation. J. Mammal. 2017, 98, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Crittenden, A.; Erbe, C.; Street, A.; Wellard, R.; Robb, K. Burrunan babble: Acoustic characterization of the whistles and burst-pulse sounds of a critically endangered dolphin. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2025, 12, 241949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robb, K.; Richards, S.A.; Foord, C.S.; Henderson, A.F.; Sondermeyer, N. A Conservation Crisis: Long-Term Population Dynamics and Mass Mortality Event in the Critically Endangered Burrunan Dolphin (Tursiops australis); Marine Mammal Foundation (MMF): Hampton East, Melbourne, Australia, 2026; in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Boon, P.; Cook, P.; Woodland, R. The Gippsland Lakes: Management challenges posed by long-term environmental change. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2016, 67, 721–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, E.A.; Jones, B.L.; Austin, M.; Eierman, L.; Collom, K.A.; Melo-Santos, G.; Castelblanco-Martínez, N.; Arreola, M.R.; Sánchez-Okrucky, R.; Rieucau, G. Signature whistle use and changes in whistle emission rate in a rehabilitated rough-toothed dolphin. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1278299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fandel, A.D.; Silva, K.; Bailey, H. Vocal signatures affected by population identity and environmental sound levels. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, P.; Peterson, J.; Gordon-Brown, L. Channel dredging trials at Lakes Entrance, Australia: A GIS-based approach for monitoring and assessing bathymetric change. J. Coast. Res. 2010, 26, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- East Gippsland Catchment Management Authority. East Gippsland Regional Catchment Strategy 2013–2019; East Gippsland Catchment Management Authority: Bairnsdale, Victoria, Australia, 2013.

- Shane, S.; Wells, R.; Würsig, B. Ecology, behavior and social organization of the bottlenose dolphin: A review. Mar. Mammal Sci. 1986, 2, 34–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Würsig, B.; Jefferson, T. Methods of photo-identification for small cetaceans. In Individual Recognition of Cetaceans: Use of Photo-Identification and Other Techniques to Estimate Population Parameters; Hammond, P.S., Mizroch, S.A., Donovan, G.P., Eds.; The International Whaling Commission: Cambridge, UK, 1990; pp. 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Urian, K.; Gorgone, A.; Read, A.; Balmer, B.; Wells, R.S.; Berggren, P.; Durban, J.; Eguchi, T.; Rayment, W.; Hammond, P.S. Recommendations for photo-identification methods used in capture-recapture models with cetaceans. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2015, 31, 298–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urian, K.W.; Hofmann, S.; Wells, R.S.; Read, A.J. Fine-scale population structure of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in Tampa Bay, Florida. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2009, 25, 619–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbe, C.; Wei, C. Odontocete sounds. In Marine Mammal Acoustics in a Noisy Ocean; Erbe, C., Houser, D., Bowles, A., Porter, M., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 267–350. [Google Scholar]

- Erbe, C.; Salgado-Kent, C.; De Winter, S.; Marley, S.; Ward, R. Matching signature whistles with photo-identification of Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus) in the Fremantle Inner Harbour, Western Australia. Acoust. Aust. 2020, 48, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.L.; Connor, R.C.; Montgomery, S.H. Social and vocal complexity in bottlenose dolphins. Trends Neurosci. 2022, 45, 881–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.L.H.; Sayigh, L.S.; Blum, J.E.; Wells, R.S. Signature-whistle production in undisturbed free-ranging bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). Proc. Biol. Sci. 2004, 271, 1043–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esch, H.C.; Sayigh, L.S.; Blum, J.E.; Wells, R.S. Whistles as potential indicators of stress in bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). J. Mammal. 2009, 90, 638–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowans, S. Grouping behaviors of dolphins and other toothed whales. In Ethology and Behavioral Ecology of Odontocetes; Würsig, B., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sayigh, L.S.; Tyack, P.L.; Wells, R.S.; Scott, M.D.; Irvine, A.B. Sex difference in signature whistle production of free-ranging bottlenose dolphins, Tursiops truncates. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1995, 36, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolker, R.; Pepper, J.W. Whistle convergence among allied male bottlenose dolphins (Delphinidae, Tursiops sp.). Ethology 1999, 105, 595–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foord, C.; Rowe, K.; Robb, K. Cetacean biodiversity, spatial and temporal trends based on stranding records (1920–2016), Victoria, Australia. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadway, M.; Shelley, J.K.; Serafin, B.S.; Howard, V.A.; Samuelson, M.M.; Lyn, H. Individualized use of signature whistles by bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) during an introduction. Zoo Biol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Manna, G.; Rako-Gospić, N.; Pace, D.S.; Bonizzoni, S.; Di Iorio, L.; Polimeno, L.; Perretti, F.; Ronchetti, F.; Giacomini, G.; Pavan, G.; et al. Determinants of variability in signature whistles of the Mediterranean common bottlenose dolphin. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kriesell, H.J.; Elwen, S.H.; Nastasi, A.; Gridley, T. Identification and characteristics of signature whistles in wild bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) from Namibia. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gridley, T.; Cockcroft, V.; Hawkins, E.; Blewitt, M.; Morisaka, T.; Janik, V. Signature whistles in free-ranging populations of Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins, Tursiops aduncus. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2014, 30, 512–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longden, E.G.; Elwen, S.H.; McGovern, B.; James, B.S.; Embling, C.B.; Gridley, T. Mark–recapture of individually distinctive calls—A case study with signature whistles of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus). J. Mammal. 2020, 101, 1289–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Start Frequency [kHz] | End Frequency [kHz] | Min Frequency [kHz] | Max Frequency [kHz] | Duration [s] | Extrema [#] | Inflection Points [#] | Steps [#] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | 5.91 | 7.97 | 4.24 | 12.43 | 0.44 | 1.87 | 1.31 | 1.13 |

| std | 2.33 | 3.83 | 1.88 | 3.98 | 0.25 | 2.14 | 1.87 | 2.45 |

| min | 0.84 | 2.06 | 0.61 | 5.18 | 0.04 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10% | 3.59 | 4.13 | 1.97 | 6.71 | 0.10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 25% | 4.69 | 5.44 | 2.45 | 9.15 | 0.26 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| median | 5.63 | 6.80 | 4.38 | 12.63 | 0.41 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 75% | 6.94 | 9.70 | 5.65 | 15.70 | 0.63 | 4 | 3 | 0 |

| 90% | 8.52 | 13.78 | 6.65 | 17.57 | 0.70 | 4 | 3 | 5 |

| max | 17.53 | 21.56 | 8.59 | 22.34 | 1.34 | 11 | 10 | 16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Crittenden, A.; Robb, K.; Erbe, C. Acoustic Identity: Linking Signature Whistles and Visual Identification in a Threatened Dolphin Population. Animals 2025, 15, 3259. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223259

Crittenden A, Robb K, Erbe C. Acoustic Identity: Linking Signature Whistles and Visual Identification in a Threatened Dolphin Population. Animals. 2025; 15(22):3259. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223259

Chicago/Turabian StyleCrittenden, Amber, Kate Robb, and Christine Erbe. 2025. "Acoustic Identity: Linking Signature Whistles and Visual Identification in a Threatened Dolphin Population" Animals 15, no. 22: 3259. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223259

APA StyleCrittenden, A., Robb, K., & Erbe, C. (2025). Acoustic Identity: Linking Signature Whistles and Visual Identification in a Threatened Dolphin Population. Animals, 15(22), 3259. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15223259