From Removal to Selective Control: Perspectives on Predation Management in Spanish Hunting Grounds

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Context

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

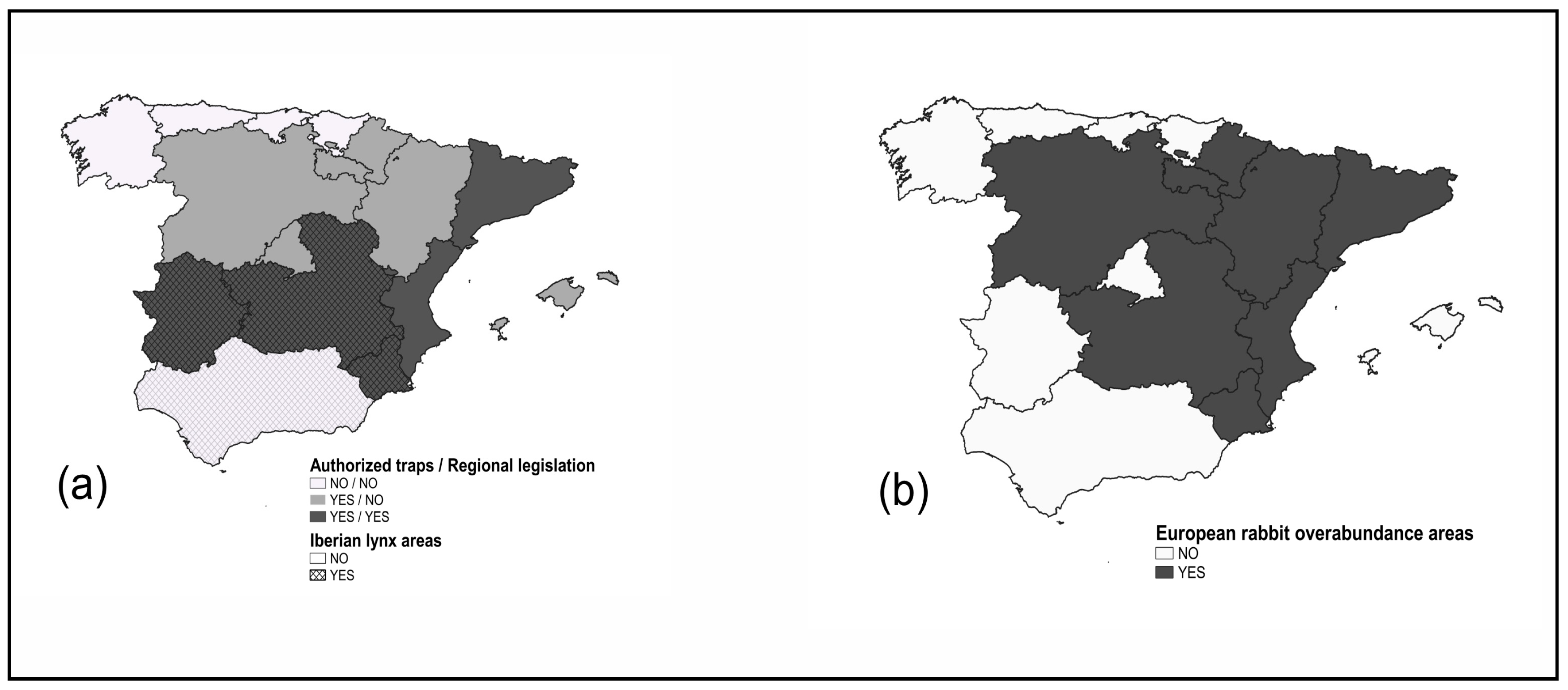

2.2.1. Survey on Predator Control Regulations and Methods Permitted by Regional Authorities

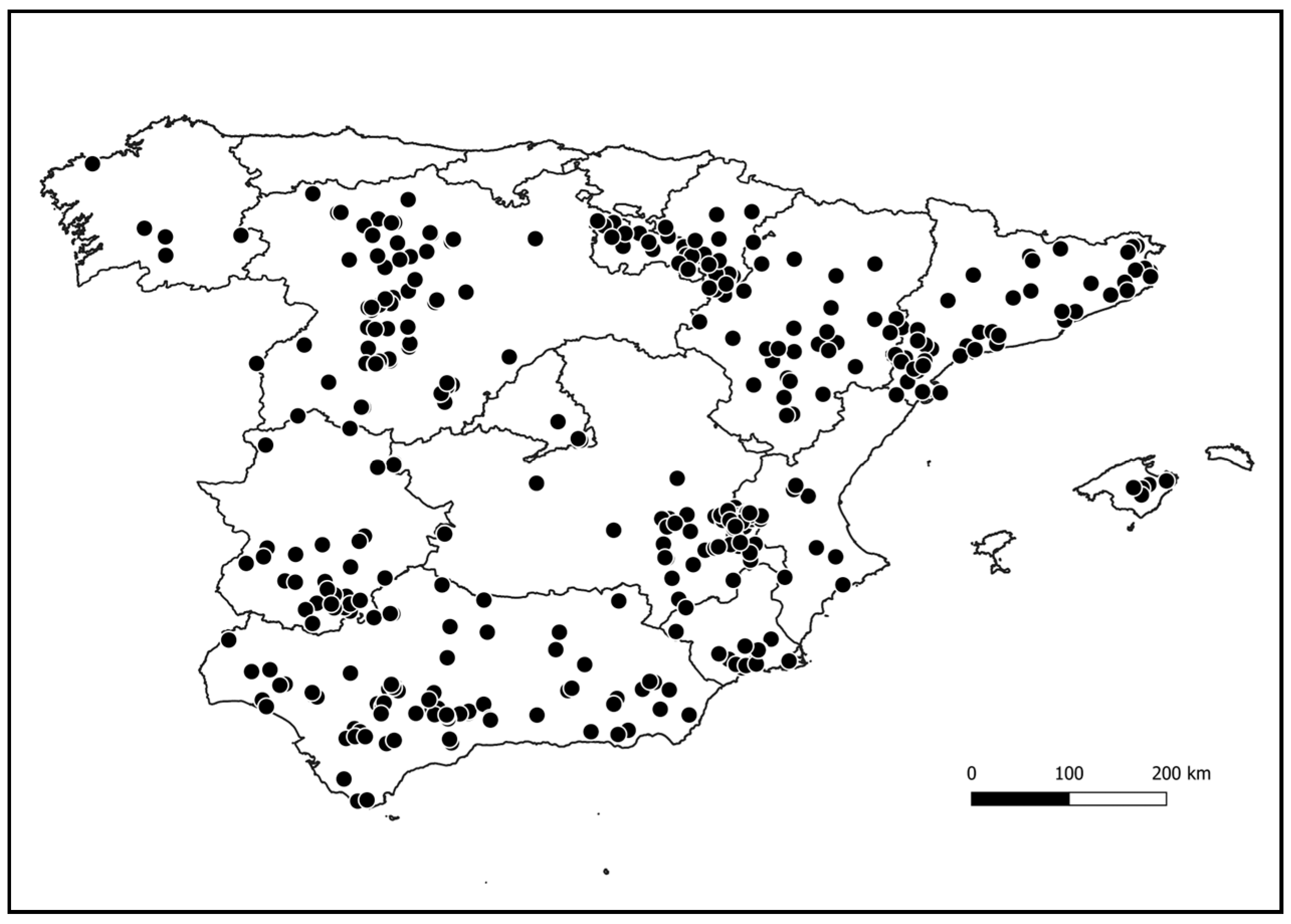

2.2.2. Questionnaire on Predation Control Conducted in Hunting Grounds

2.2.3. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Survey on Predator Control Regulations and Methods Permitted by Regional Authorities

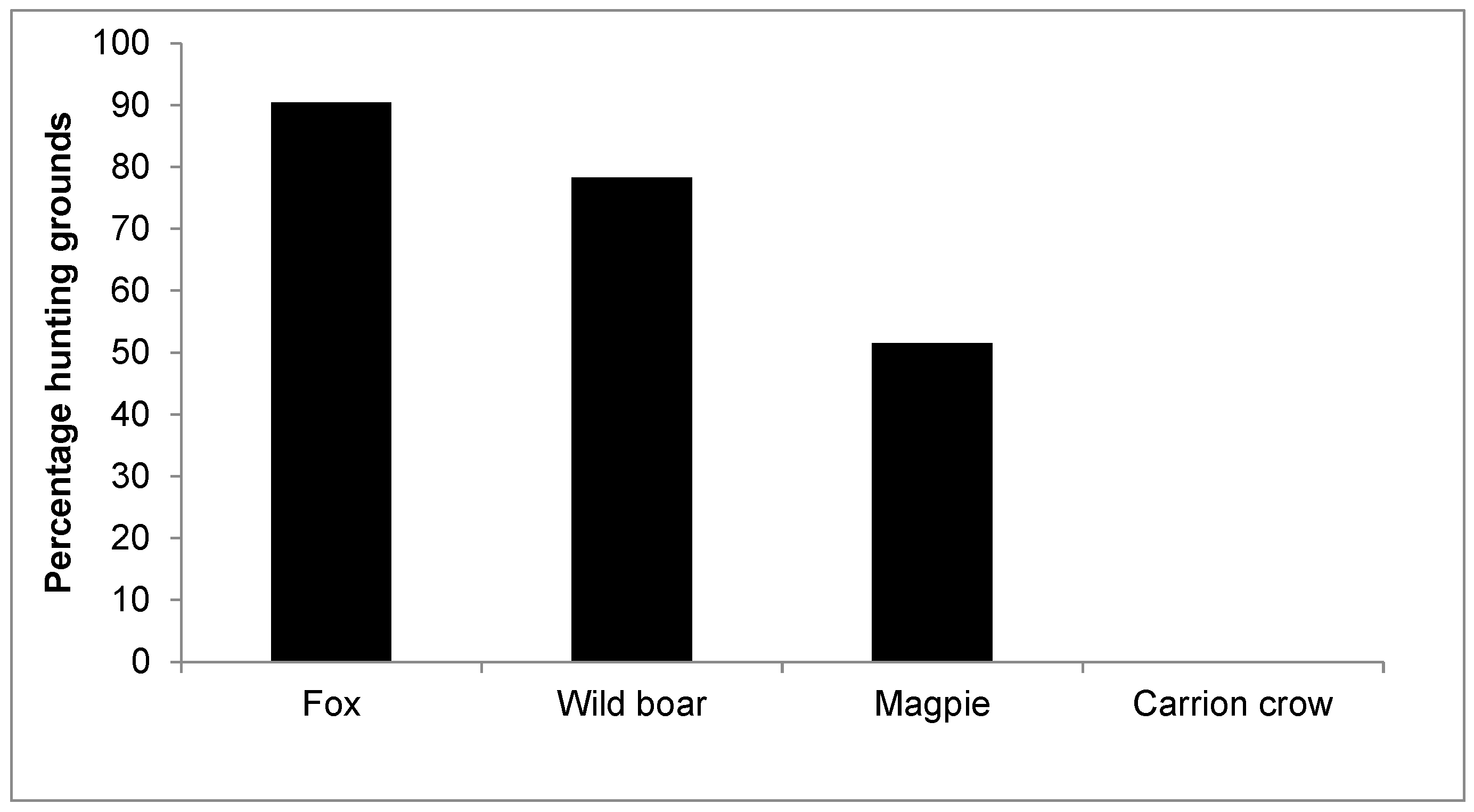

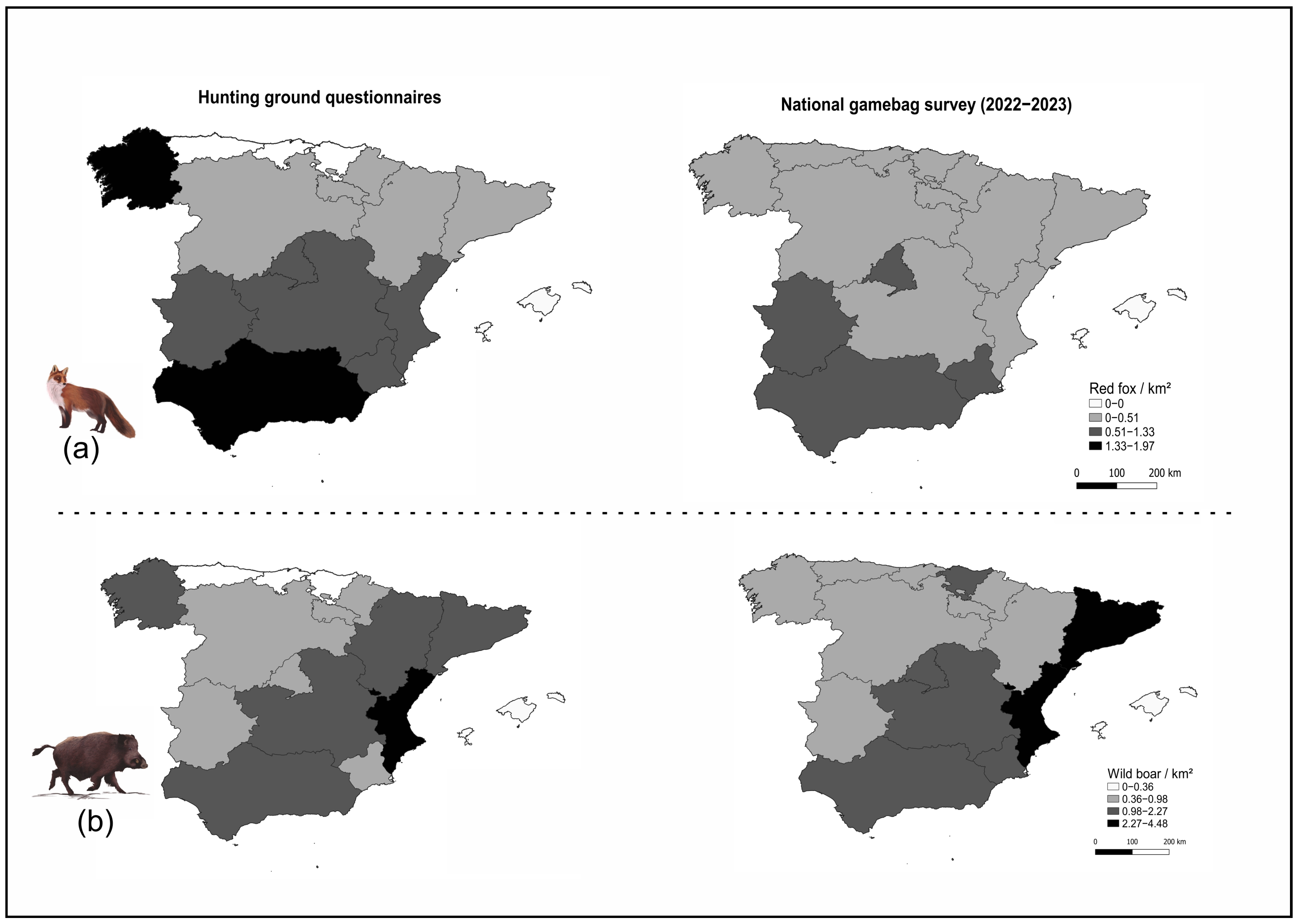

3.2. Questionnaire on Predation Control Conducted in Hunting Grounds

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions and Management Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- (1)

- Basic data of the hunting ground (unit of analysis) included surface area, responsibility of the respondent concerning game management, agricultural and forest management, presence of fences, and type of gamekeeping. The latter questions allowed us to address whether hunters or gamekeepers (employed part-time or full-time) conducted predator control.

- (2)

- Habitat management measures: food and water provision (water troughs and ponds), agricultural management for game and wildlife (including game crops, management and conservation of stubbles and fallows), agri-environmental measures funded by public schemes (measures similar to the agricultural ones), and forest/shrub management (including forest and shrub clearing). Respondents were asked whether the management was implemented (or not), the number of measures or the total surface involved, the sources of funding for the management, and practical questions (such as the types of seeds in the agricultural measures).

- (3)

- Predator control: species, methods (hunting and traps), and number of animals killed.

- (4)

- Partridge hunting: types of hunting, harvesting levels, and restraint measures when implemented.

- (5)

- Partridge releasing: number of partridges released.

Appendix B

| Region | Red Fox | Wild Boar | Magpie | Carrion Crow | Jackdaw | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vulpes vulpes | Sus scrofa | Pica pica | Corvus corone | Corvus monedula | ||

| Andalucía | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Aragón | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Asturias | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yellow-legged gull * |

| Cantabria | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yellow-legged gull * |

| Castilla La Mancha | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Castilla y León | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Cataluña | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | |

| Comunidad Valenciana | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | |

| Comunidad de Madrid | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Extremadura | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Galicia | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yellow-legged gull * |

| Islas Baleares | No | No | No | No | No | |

| La Rioja | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Black-headed gull ** |

| Navarra | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | |

| País Vasco *** | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yellow-legged gull * |

| Región de Murcia | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yellow-legged gull * |

Appendix C

| Red Fox | Corvids | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Non-Locking Spanish Snare | Wisconsin Snare | Collarum | Belisle Selective | Cage-Trap | Larsen Trap | Ladder Trap |

| Aragón | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Castilla La Mancha | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Castilla y León | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Cataluña | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Comunidad Valenciana | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Madrid | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Murcia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Extremadura | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| La Rioja | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

Appendix D

| Red fox | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

| Castilla La Mancha | ||||||||||||

| Comunidad de Madrid | ||||||||||||

| Región de Murcia | ||||||||||||

| Cataluña | ||||||||||||

| Extremadura | ||||||||||||

| Comunidad Valenciana | ||||||||||||

| La Rioja | ||||||||||||

| Magpie | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

| Castilla La Mancha | ||||||||||||

| Comunidad de Madrid | ||||||||||||

| Región de Murcia | ||||||||||||

| Cataluña | ||||||||||||

| Extremadura | * | * | ||||||||||

| Comunidad Valenciana | ||||||||||||

| Comunidad Foral de Navarra | ||||||||||||

| La Rioja |

References

- Leopold, A. Game Management; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.K.; Pullin, A.S.; Stewart, G.B.; Sutherland, W.J. Effectiveness of Predator Removal for Enhancing Bird Populations. Conserv. Biol. 2010, 24, 820–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, J.C.; Tapper, S.C. Control of mammalian predators in game management and conservation. Mammal Rev. 1996, 26, 127–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farfán, M.Á.; Duarte, J.; Meriggi, A.; Reino, L.; Viñuela, J.; Vargas, J.M. The red-legged partridge: A historical overview on distribution, status, research and hunting. In The Future of the Red-Legged Partridge. Science, Hunting and Conservation; Casas, F., García, J.T., Eds.; Springer Nature: Gewerbestrasse, Switzerland, 2022; p. 302. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Ruiz, F.; Ferreras, P. Conocimiento científico sobre la gestión de depredadores generalistas en España: El caso del zorro (Vulpes vulpes) y la urraca (Pica pica). Rev. Ecosistemas 2013, 22, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, P.C.; Acevedo, P.; Melo-Ferreira, J. Iberian Hare Lepus granatensis Rosenhauer, 1856. In Handbook of the Mammals of Europe; Springer Nature: Gewerbestrasse, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1–23. ISBN 9783319650388. [Google Scholar]

- Delibes-Mateos, M.; Redpath, S.M.; Angulo, E.; Ferreras, P.; Villafuerte, R. Rabbits as a keystone species in southern Europe. Biol. Conserv. 2007, 137, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Márquez, C. El Control de Depredadores en España: Análisis Histórico, Incidencia Actual del uso de cebos Envenenados y Perspectiva de Futuro. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Málaga, Málaga, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Conferencia Sectorial del Medio Ambiente y Directrices Técnicas Para La Captura De Especies Cinegéticas Predadoras: Homologación De Métodos De Captura y Acreditación. In Proceedings of the Conferencia Sectorial del Medio Ambiente, Madrid, Spain, 4–16 June 2011.

- Díaz-Ruiz, F.; Delibes-Mateos, M.; García-Moreno, J.L.; María López-Martín, J.; Ferreira, C.; Ferreras, P. Biogeographical patterns in the diet of an opportunistic predator: The red fox Vulpes vulpes in the Iberian Peninsula. Mammal Rev. 2013, 43, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J. Urraca—Pica pica Linnaeus, 1758. In Enciclopedia Virtual de los Vertebrados Españoles; CSIC-Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (MNCN): Madrid, Spain, 2011; Available online: https://www.vertebradosibericos.org/aves/picpic.html (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Massei, G.; Kindberg, J.; Licoppe, A.; Gačić, D.; Šprem, N.; Kamler, J.; Baubet, E.; Hohmann, U.; Monaco, A.; Ozoliņš, J.; et al. Wild boar populations up, numbers of hunters down? A review of trends and implications for Europe. Pest Manag. Sci. 2015, 71, 492–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpio, A.J.; Guerrero-Casado, J.; Tortosa, F.S.; Vicente, J. Predation of simulated red-legged partridge nests in big game estates from South Central Spain. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2014, 60, 391–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barasona, J.A.; Carpio, A.; Boadella, M.; Gortazar, C.; Piñeiro, X.; Zumalacárregui, C.; Vicente, J.; Viñuela, J. Expansion of native wild boar populations is a new threat for semi-arid wetland areas. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 125, 107563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MITERD Avance del Anuario de Estadística Forestal 2023; Centro de Publicaciones, Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y Reto Demográfico: Madrid, Spain, 2025.

- González, L.M.; Oria, J.; Sánchez, R.; Margalida, A.; Aranda, A.; Prada, L.; Caldera, J.; Molina, J.I. Status and habitat changes in the endangered Spanish Imperial Eagle Aquila adalberti population during 1974–2004: Implications for its recovery. Bird Conserv. Int. 2008, 18, 242–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, G.; López-Parra, M.; Fernández, L.; Arenas, R.; Garrote, G.; García-Tardío, M.; Del Rey-Wamba, T.; Rojas, E.; Alves, J.; Sarmento, P. Iberian lynx conservation programme in the last 22 years. Cat News 2024, 17, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Casas, F.; Tinaut, A. The predation of hatching Red-legged Partridges Alectoris rufa by the harvester ant Messor barbarus. Bird Study 2022, 69, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, J.; Farfán, M.; Guerrero, J. Importancia de la predación en el ciclo anual de la perdiz roja. In Especialista en Control de Predadores; Garrido, J., Ed.; FEDENCA-EEC: Madrid, Spain, 2008; pp. 133–141. [Google Scholar]

- Delibes-Mateos, M.; Delibes, A. Pets becoming established in the wild: Free–living Vietnamese potbellied pigs in Spain. Anim. Biodivers. Conserv. 2014, 2, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, V.; Álvares, F.; Layna, J.F.; González, J.L.; Herrera, J.; de Lucas, J.; Louppe, V.; Rosalino, L.M. Raccoon (Procyon lotor) in Iberia: Status update and suitable habitats for an invasive carnivore. J. Nat. Conserv. 2022, 66, 126142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delibes-Mateos, M.; Díaz-Fernández, S.; Ferreras, P.; Viñuela, J.; Arroyo, B. The role of economic and social factors driving predator control in small-game estates in central Spain. Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villafuerte, R.; Viñuela, J.; Blanco, J.C. Extensive predator persecution caused by population crash in a game species: The case of red kites and rabbits in Spain. Biol. Conserv. 1998, 84, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beja, P.; Gordinho, L.; Reino, L.; Loureiro, F.; Santos-Reis, M.; Borralho, R. Predator abundance in relation to small game management in southern Portugal: Conservation implications. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2009, 55, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrull, J.; Mate, I.; Casanovas, J.G.; Salicrú, M.; Gosàlbez, J. Selectivity of mammalian predator control in managed hunting areas: An example in a Mediterranean environment. Mammalia 2011, 75, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.; Torres, A.; Vieira-pinto, M.; Tizado, E.J.; Carlos, S. Is the Iberian lynx a hunters’ ally? A case study from a reintroduced population in Portugal. J. Nat. Conserv. 2024, 81, 126660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, J.; Nuñez-Arjona, J.C.; Mougeot, F.; Ferreras, P.; González, L.M.; García-Domínguez, F.; Muñoz-Igualada, J.; Palacios, M.J.; Pla, S.; Rueda, C.; et al. Restoring apex predators can reduce mesopredator abundances. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 238, 108234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, J.; Farfán, M.A.; Fa, J.E.; Vargas, J.M. How effective and selective is traditional Red Fox snaring? Galemys Span. J. Mammal. 2012, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Igualada, J.; Shivik, J.A.; Domínguez, F.G.; Lara, J.; González, L.M. Evaluation of Cage-Traps and Cable Restraint Devices to Capture Red Foxes in Spain. J. Wildl. Manag. 2008, 72, 830–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Ruiz, F. Ecología y Gestión de Depredadores Generalistas: El caso del Zorro (Vulpes vulpes) y la Urraca (Pica pica). Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, Ciudad Real, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Herranz, J. Efectos de la Depredación y del Control de Depredadores Sobre la caza Menor en Castilla-La Mancha. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, Ciudad Real, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Márquez, C.; Vargas, J.M.; Villafuerte, R.; Fa, J.E. Risk mapping of illegal poisoning of avian and mammalian predators. J. Wildl. Manag. 2013, 77, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, F.; Viñuela, J. Agricultural practices or game management: Which is the key to improve red-legged partridge nesting success in agricultural landscapes? Environ. Conserv. 2010, 37, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, P.J.C.; Stoate, C.; Szczur, J.; Norris, K. Predator reduction with habitat management can improve songbird nest success. J. Wildl. Manag. 2014, 78, 402–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAPA. Estrategia Nacional de Gestión Cinegética; Unidad Editora, Ministerio de Agricultural, Pesca y Alimentación: Madrid, Spain, 2022.

- Urzay, M.; Albisu, J.; Villanueva, L.F.; Castillo-Contreras, R.; Sánchez–García, C. Estudio del Impacto Económico, Social y Ambiental de la Caza en España; Fundación Artemisan y Consultora Independiente, Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación (MAPA): Ciudad Real, Spain, 2025.

- Herruzo, C.; Martinez-Jauregui, M. Trends in hunters, hunting grounds and big game harvest in Spain. For. Syst. 2013, 22, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo, B.; Caro, J.; Delibes-Mateos, M. Social and Economic Aspects of Red-Legged Partridge Hunting and Management in Spain. In The Future of the Red-Legged Partridge: Science, Hunting and Conservation; Casas, F., García, J.T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 275–295. ISBN 978-3-030-96341-5. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-García, C.; Powolny, T.; Lormée, H.; Dias, S.; Sardà-Palomera, F.; Bota, G.; Arroyo, B. Habitat management carried out by hunters in the European turtle dove western flyway: Opportunities and pitfalls for linking with sustainable hunting. J. Nat. Conserv. 2024, 78, 126561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; Version 4.4.1; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: http://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Jenks, G.F. The Data Model Concept in Statistical Mapping. Int. Yearb. Cartogr. 1967, 7, 186–190. [Google Scholar]

- QGIS Development Team QGIS. Open source Geospatial Foundation Project. 2025. Available online: http://qgis.org/ (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Muñoz-Igualada, J.; Shivik, J.A.; Domínguez, F.G.; Mariano González, L.; Aranda Moreno, A.; Fernández Olalla, M.; Alves García, C. Traditional and New Cable Restraint Systems to Capture Fox in Central Spain. J. Wildl. Manag. 2010, 74, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Ruiz, F.; García, J.T.; Pérez-Rodríguez, L.; Ferreras, P. Experimental evaluation of live cage-traps for black-billed magpies Pica pica management in Spain. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2010, 56, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Ruiz, F.; Zarca, J.C.; Delibes-Mateos, M.; Ferreras, P. Feeding habits of Black-billed Magpie during the breeding season in Mediterranean Iberia: The role of birds and eggs. Bird Study 2015, 62, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oja, R.; Soe, E.; Valdmann, H.; Saarma, U. Non-invasive genetics outperforms morphological methods in faecal dietary analysis, revealing wild boar as a considerable conservation concern for ground-nesting birds. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gortázar, C.; Fernández-de-Simón, J. One tool in the box: The role of hunters in mitigating the damages associated to abundant wildlife. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2022, 68, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conejero, C.; Ramón, J.; Olvera, L.; Crespo, C.G.; Bravo, A.R.; Contreras, R.C.; Tampach, S.; Velarde, R.; Mentaberre, G. Assessing mammal trapping standards in wild boar drop-net capture. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 15090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrero, J.; Sergio, A.G. Diet of wild boar Sus scrofa L. and crop damage in an intensive agroecosystem. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2006, 52, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolopo, D.; Canestrari, D.; Baglione, V. Corneja negra–Corvus corone Linnaeus, 1758. In Enciclopedia Virtual de los Vertebrados Españoles; CSIC-Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (MNCN): Madrid, Spain, 2015; Available online: https://digital.csic.es/bitstream/10261/111627/3/corcor_v2.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Soler, M. Grajilla—Corvus monedula Linnaeus, 1758. In Enciclopedia Virtual de los Vertebrados Españoles; CSIC-Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales (MNCN): Madrid, Spain, 2016; Available online: https://www.vertebradosibericos.org/aves/cormon.html (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Loss, S.R.; Boughton, B.; Cady, S.M.; Londe, D.W.; McKinney, C.; O’Connell, T.J.; Riggs, G.J.; Robertson, E.P. Review and synthesis of the global literature on domestic cat impacts on wildlife. J. Anim. Ecol. 2022, 91, 1361–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, F.M.; Bonnaud, E.; Vidal, E.; Tershy, B.R.; Zavaleta, E.S.; Josh Donlan, C.; Keitt, B.S.; Le Corre, M.; Horwath, S.V.; Nogales, M. A global review of the impacts of invasive cats on island endangered vertebrates. Glob. Change Biol. 2011, 17, 3503–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Región de Murcia. Directrices Técnicas para la Captura de Especies Cinegéticas Predadoras: Homologación de Métodos y Acreditación de Usuarios. Murcia, Spain, 2021. Available online: https://www.carm.es/web/pagina?IDCONTENIDO=17218&IDTIPO=246&RASTRO=c2889$m58245,58256,58832 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Lázaro, C.; Castillo-Contreras, R.; Sánchez–García, C. Free-roaming domestic cats in Natura 2000 sites of central Spain: Home range, distance travelled and management implications. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2024, 270, 106136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Fernández, S.; Arroyo, B.; Casas, F.; Martinez-Haro, M.; Viñuela, J. Effect of Game Management on Wild Red-Legged Partridge Abundance. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, C.; Pérez, J.A.; Díez, C.; Alonso, M.E.; Bartolomé, D.J.; Prieto, R.; Tizado, E.J.; Gaudioso, V.R. Does targeted management work for red-legged partridges Alectoris rufa? Twelve years of the ‘Finca de Matallana’ demonstration project. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2017, 63, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpio, A.J.; Queirós, J.; Laguna, E.; Jiménez-Ruiz, S.; Vicente, J.; Alves, P.C.; Acevedo, P. Understanding the impact of wild boar on the European wild rabbit and red-legged partridge populations using a diet metabarcoding approach. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2023, 69, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porteus, T.A.; Reynolds, J.C.; McAllister, M.K. Population dynamics of foxes during restricted-area culling in Britain: Advancing understanding through state-space modelling of culling records. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GWCT. GWCT General Licence Survey Results December 2019. Available online: https://www.gwct.org.uk/media/1066182/defrasub.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- de Ridder, N.; Knight, A. The Animal Welfare Consequences and Moral Implications of Lethal and Non-Lethal Fox Control Methods. Animals 2024, 14, 1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palencia, P.; Blome, S.; Brook, R.K.; Ferroglio, E.; Jo, Y.S.; Linden, A.; Montoro, V.; Penrith, M.L.; Plhal, R.; Vicente, J.; et al. Tools and opportunities for African swine fever control in wild boar and feral pigs: A review. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2023, 69, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morters, M.K.; Restif, O.; Hampson, K.; Cleaveland, S.; Wood, J.L.N.; Conlan, A.J.K. Evidence-based control of canine rabies: A critical review of population density reduction. J. Anim. Ecol. 2013, 82, 6–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vajas, P.; Calenge, C.; Richard, E.; Fattebert, J.; Rousset, C.; Saïd, S.; Baubet, E. Many, large and early: Hunting pressure on wild boar relates to simple metrics of hunting effort. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 698, 134251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delibes-Mateos, M.; Ferreras, P.; Villafuerte, R. Rabbit populations and game management: The situation after 15 years of rabbit haemorrhagic disease. Biodivers. Conserv. 2008, 17, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, J.A.A.; García, J.A.F.; Jiménez, F.V.; Touza, J.M.Q. A descriptive study of poisoners and users of other indiscriminate means to illegally control wildlife in Spain. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2024, 6, e13194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region | Control Permissions (Period) | Certified Predator Control Specialists |

|---|---|---|

| Castilla y León | 843 (2014–2024) * | – |

| Castilla-La Mancha | 745.8 (2020–2023) ** | 34.8 (2020–2023) |

| Navarra | 76 (2014–2023) * | 5 (2014–2023) |

| Madrid | 50 (2014–2023) ** | 60 (2014–2023) |

| Extremadura | 45 (2021–2023) ** | 55.3 (2014–2023) |

| Aragón | 43.4 (2014–2020) *** | – |

| La Rioja | 22.3 (2014–2023) ** | – |

| Murcia | 2 (2022–2023) ** | 16.3 (2021–2023) |

| Com. Valenciana | – | 368.2 (2015–2023) |

| Cataluña | – | 98 (2014–2023) |

| (a) Habitat Management (%) | No Measures | Agricultural | Forest | ||

| All grounds | 48.80 | 27.38 | 23.80 | ||

| No control | 38.98 | 18.64 | 42.37 | ||

| Control | 50.41 | 28.80 | 20.77 | ||

| (b) Type of Gamekeep. (%) | Hunters | Part-time gamekeep. | Full-time gamekeep. | ||

| No control | 51.02 | 44.89 | 4.08 | ||

| Control | 50.61 | 32.4 | 16.97 | ||

| (c) Control intensity (n culled/km2) | Hunters | Part-time | Full-time | H | p value |

| Red fox | 0.42 | 0.51 | 0.74 | 47.6 | <0.001 |

| Magpie | 0.00 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 14.5 | <0.001 |

| Wild boar | 0.65 | 0.41 | 0.09 | 7.1 | 0.008 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Torres, J.A.; Tizado, E.J.; Castillo-Contreras, R.; Villanueva, L.F.; Sánchez-García, C. From Removal to Selective Control: Perspectives on Predation Management in Spanish Hunting Grounds. Animals 2025, 15, 2917. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15192917

Torres JA, Tizado EJ, Castillo-Contreras R, Villanueva LF, Sánchez-García C. From Removal to Selective Control: Perspectives on Predation Management in Spanish Hunting Grounds. Animals. 2025; 15(19):2917. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15192917

Chicago/Turabian StyleTorres, José A., E. Jorge Tizado, Raquel Castillo-Contreras, Luis F. Villanueva, and Carlos Sánchez-García. 2025. "From Removal to Selective Control: Perspectives on Predation Management in Spanish Hunting Grounds" Animals 15, no. 19: 2917. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15192917

APA StyleTorres, J. A., Tizado, E. J., Castillo-Contreras, R., Villanueva, L. F., & Sánchez-García, C. (2025). From Removal to Selective Control: Perspectives on Predation Management in Spanish Hunting Grounds. Animals, 15(19), 2917. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15192917