Simple Summary

In Canada, animal protection law, duty to care for animals, is primarily the constitutional responsibility of the provincial governments (Administrative Law) for both farm and companion animals while cruelty to animals is addressed by federal Criminal Code. The federal government has some administrative laws whereas the province has no criminal statutes. Federal administrative law on humane transport of animals was amended in 2020. The previous “Prohibition of Overcrowding” Sec 140 was repealed and replaced by Sec 148 “Overcrowding”. New statutory language did not include a measurable or mathematical threshold of overcrowding. To understand how these narrative prohibitions are enforced, this paper reviews reports of the adjudication of appeals of Administrative Monetary Penalties assigned to violations of the prohibition of overcrowding. This paper reflects upon the history of the regulation of humane transport of livestock in Canada and possible explanation of reluctance for a scientific regulator to incorporate widely accepted numerical standards in promoting a culture of humane transport of livestock.

Abstract

Administrative law is about articulating norms and promoting the adoption and enforcement of human behaviour practices in areas where individual choice conflicts with the public good. Law must fairly describe to the citizenry what is allowed and what is conditionally restricted by administrative law and what is prohibited in criminal law. The conditional use of animals in industrial production of food and fibre for human consumption is allowed (non-criminal), but the conditions which are considered acceptable by society are changing. Humane transportation of livestock is a public concern and the temptation of transporters to load as many animals as possible is an easily understood risk to animal welfare. Livestock hauling has been regulated in Canada since 1857 and is currently regulated by the Health of Animals (Act) Regulations Part XII and enforced nationally by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency. After over 30 years of challenging industry consultation, a major revision to the humane transport provisions was proclaimed in 2020. Surprisingly, the revision failed to articulate numerical thresholds that clearly indicate an overcrowding violation. This paper reviews 20 cases from 2004 to 2024 where transporters appealed a penalty for overcrowding livestock transported by land. The paper describes the decision to penalize transporters where there is no bright line definition of an offence. The paper suggests both regulator and regulated choose to work in an intentionally inefficient institutional arrangement, preferring opacity to clarity in what constitutes a violation in law, because “that’s the way we like it”.

1. Introduction

In 2006, the World Organization for Animal Health (Office International des Epizooties, now the WOAH) recommended animal transport times be kept to a minimum with sufficient space allowance for animals to lie down during transport, with consideration given for climate and ventilation capacity of transport vehicles [1] (now Terrestrial Code, Chapter 7.3). This paper reviews how Canada’s prohibition of overcrowding fails to accomplish this mandate and does not approach the recommendation to assure animals can lie down during transport. Neither the WOAH recommendation nor the Canadian legislation articulate numeric thresholds of limits to crowding.

As a signatory to the OIE/WOAH, Canadian scientists in 2008 believed that global livestock welfare transport standards would soon follow the 2006 international agreement [2]. Almost two decades later, there still is no international consensus of the minimum space that should be allocated to a group of livestock in transport, a question that must have an objective scientific (numerical) solution. The concerned citizen can intuit that an animal needs some minimal space in transit to not experience stress and on longer trips, perhaps, to remain alive.

In Canada, the primary humane transportation of animals’ law is at the national level and has been enforced for decades. This law went under complete revision in 2020. The current humane transportation of animals’ national law paradigm was introduced in 1977 in response to high visibility errors made in the then declining transportation of cattle by rail [3]. The century of livestock transport by rail was replaced by road transport with no cattle transported by rail by the mid-1980s [4]. In regulating rail transport, the regulator addressed a very small client base, primarily the Canadian National Railway and Canadian Pacific Railway. The livestock industry adoption of road transport extended the regulated pool to thousands of regulated entities.

In response to the comprehensive shift in regulatory space, rail car v. truck trailer, the regulator initiated a consultation in 1992 which persisted unabated to a final resolution in 2020, a 28-year consultation period, evidence of a highly politicized arena [3]. Despite the long history and prolonged contention surrounding humane livestock transport, there has never been a scientific measure of overcrowding developed and recognized in law. Numerical thresholds are the norm in administrative law, from food holding temperature to maximal residue limits of chemicals; the specificity of law is necessary to make possible fair enforcement and compliance.

Real world experience of animal handling and transport of meat pigs, for example, provides intuitive conviction that upon occasion a small percentage of slaughter pigs arrive at the abattoir dead or severely disabled due to fatigue-hyperthermia. This outcome could have been avoided by reducing the number of pigs in a compartment so that they could simultaneously lie down and rest (fatigue avoidance). These dead-on-arrival (DOA) and pathologically recumbent (pink and panting) individuals are easily identified. Each individual pig dying from overcrowding induced fatigue-hyperthermia exertional stress experiences very poor animal welfare and has suffered during transit [5]. This is an example of avoidable animal suffering that society agrees should be prohibited.

This paper reviews case adjudication in Canada where transporters are challenging an enforcement action, a monetary penalty, of the offence of livestock overcrowding in transit where there is no science-based measurement, no numerical threshold identified in law as violative. This paper will review how adjudication frames the offences without an objective measurement in humane transport law in Canada. This paper will address the hypothesis that the lack of scientific/numerical threshold for enforcement of the prohibition of overcrowding of livestock in transit is a sub-optimal and a technically correctable regulatory situation. The paper will also postulate as to why the vague legal description of an overcrowding violation was expanded, but not substantively improved, in the 2020 complete revision of the regulation (Table 1).

Table 1.

Change in the statutory wording of the National Prohibition of Overcrowding.

The remainder of this paper is constructed into four parts; (1) a brief history of the Canadian regulation of livestock in transport; (2) a framework for differentiating the nature of “good” from other types of legislation; (3) a case study of a series of legal decisions on appeal of violation and penalties of overcrowding in transit; and (4) a largely narrative reflection to increase the understanding of common problems in creating and delivery of good animal protection legislation by critique of the Canadian federal law prohibiting overcrowding of livestock in transit with a focus on pigs.

2. Brief History of Livestock Transportation Regulation in Canada

British criminal law had been largely exported ver batum for the purposes of governing the British North American Colonies in 1800 [6]. The prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act c. 31, was adopted in British North America in 1857 [7,8], which made it unlawful to bind sheep, calves and pigs (hog-tie) for transport to market, if more than 15 miles distant and to release them from physical restraint within half an hour of arrival at destination. Earlier animal protection provisions in policing acts of Lower-Canada 1845, allowed a Justice of the Peace to place an individual in the Common Gaol for up to a month for brutalizing draught animals in urban settings [9]. Pre-confederation townships, cities, towns and incorporated villages had delegated authority to create by-laws to respond to cruelty to animals and animals running at large [8]; two problems that remain concerns of society.

The British North America Act 1867 (Canadian Constitution) provides the federal government exclusive jurisdiction to legislate criminal offences in Canada, such as cruelty to animals [10]. The BNA 1867 or “confederation” was the administrative union of what is now Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. At confederation the 1857 colonial act respecting Cruelty to animals c.31 was incorporated as c.27 in Dominion criminal law. In 1875, c.42 An Act to prevent Cruelty to Animals While in Transit by Railway or other means of conveyance within the Dominion of Canada, was promulgated [11]. This act was focused on the prohibition of confining cattle being transported in rail cars, longer than 28 h without feed water and rest (FWR). This Canadian rule mimics the concurrent USA 28 h law that was written in 1873 but not in force until 1909 [12]. In 1887, the Canadian c.27 Animal Cruelty and c.42 Cruelty While in Transit acts were incorporated into a single act c.172 [13]. These acts were further consolidated into the 1892 Criminal Code c.29 with Section 514 Transport of Animals, addressing the FWR requirements [14].

The offence of overcrowding in transit appears in Section 387 of the 1954 Criminal Code [15], a large statute continuously under revision. Overcrowding in transit does not really fit the mens rea, evil intent requirement of criminal law. Overcrowding in commercial livestock transport is more efficiently explained by incompetence, negligence, or error. In 1975, Bill C-28 moved the regulatory oversight for humane transport of livestock from the Criminal Code to the Animal Contagious Diseases Act (ACDA), making animal mistreatment in transit administrative offences rather than the previous criminal offences.

Malicious torture, acts of sadism toward animals and staged animal fighting remain prohibited in the Criminal Code. Bill C-28 was also renamed the ACDA the Animal Diseases Protection Act. This amendment expanded the regulatory powers of a previous exclusively endemic and trans-boundary disease control act [16,17] by providing legislative space to promulgate regulations “to provide for the humane treatment of animals”, Sec 32 [16]. The Animal Disease Protection Act is continued as the current Health of Animals Act. SC 1990, c 21 (statutes of Canada, Chapter 21).

The move from criminal to administrative oversight reflects three major legal shifts in framing: (1) the type of offence calls for penalty not punishment; (2) the type of offence occurs with or without intention (strict liability offence); and (3) criminal law responds to an offence that has already happened. In theory, administrative offences can be minimized with oversight, inspection and penalization. Incarceration for non-compliance with provincial animal protection (non-criminal) law is rare, as in Canadian law, incarceration is punishment. Criminal statutes have no regulations because crimes are prohibited, a type of behaviour where there is no regulation that can make them tolerable and convicted offenders usually are incarcerated. Administrative law bravely attempts to both prevent, and respond, to anti-social behaviour.

Minimizing the pain and suffering of livestock in transit and the sanctioning of those responsible for avoidable animal suffering is largely the domain of the national veterinary infrastructure. In Canada, millions of animals move inter-provincially and internationally with no pre movement or roadside inspection for compliance. Federal inspectors are present to inspect for compliance at the live animal receiving dock of federally inspected slaughter facilities. Over 95% of animals slaughtered for food in Canada are slaughtered at federal plants, producing products which are then eligible for interprovincial and international trade [18]. Part XII, of Health of Animals Regulations, CRC, c 296, (Health of Animals Act), Transport of Animals is enforced by inspectors employed by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) who also provide the humane slaughter and sanitary inspection services at federally registered abattoirs.

Law enabling the identification and enforcement of animal protection is rare at the national level in Canada, a country with dual federalism [19]. The Canadian federal government has some features of the administrative state with the creation of empowered agencies, related to health, food safety and environmental protection, but most limits of individual freedom in Canada are created directly by provincial legislation. Under the Canadian Constitution, the provinces have authority and obligation to fund and operate the Courts and Judicial institutions. The Criminal Code, a national law with a small section re Animal Cruelty, is without an administrative agency, and is supported by uniformed police services. Discovery and prosecution of non-criminal animal law offences remains a local matter under the provincial infrastructure officers, courts and inspectorate functions.

Under dual federalism, a problem of justice emerges in treating all malingering but noncriminal citizens the same, when supporting federal administrative law such as international border control and in this case, the interprovincial movement of livestock. Justice requires that a prohibited food smuggling offence at an international airport in Québec is penalized equally with the same offence identified at a USA-Canada land crossing in British Columbia. The Canadian administrative state addressed this problem by creation of the Canadian Border Services Agency (CBSA). Effective federal policing of noncriminal offences has a problem of accessing provincial justice infrastructure for prosecution and sanctioning [20].

Each province empowers uniformed police and other individuals to act as agents of the justice system to initiate prosecutions. Canada like other British Common Law countries empower police to issue a ticket as a prosecution option for minor common offences. The receiver of the ticket can pay the penalty and decline the right to judicial review. A common choice is to present to a justice, plead guilty, and request reduction in the monetary penalty which is not based on ability to pay as are day fines in other jurisdictions [21]. The Common Offence Notice (CON) system, also known as ticketing, is housekeeping regulatory work where the uniformed officer is empowered to decide the nature of an offence is balanced with the set fine, give a ticket, or whether justice would be better served by requiring the offender to appear before a judge, the ‘Summary Conviction’ process (in Canada).

A provincial street-level [22] animal protection officer, delivering inspection and enforcement of a provincial act, may initiate prosecution by either the CON process (ticket) or initiate a prosecution via the summary conviction process. The summary conviction process is described in the Criminal Code and assures protection of the rights of the accused. Summary conviction process is mirrored in provincial offences acts and is blue collar enforcement work [23]. In proceeding with a CON there is no requirement for the officer to consult with the Crown prosecutor and no information is made accessible to public review, limiting transparency.

The summary conviction system as a process is harmonized across provinces and provincial offences. There is also a more formal indictment process for serious Criminal Code offences such as violent crime, e.g., assault, murder. Criminal Code animal offences such as cruelty to animals or criminal neglect follow the summary conviction process.

The provincial offence summary conviction process and Criminal Code summary conviction process are identical and compete for the resources of Crown prosecutors and the resources of the provincial court system. Summary conviction is used for offences where there is no set fine (complicated, or contestable offences), or where there is a set fine but the details of the incident call for a more significant penalty. In resource demand, a provincial summary conviction charge of starving your livestock requires the same process as a criminal code of animal cruelty without the requirement of proving mens rea.

The summary conviction process is straightforward but complex and burdensome, as it should be, to prevent frivolous police actions. Summary conviction requires enforcement officers to gather detailed information to be shared with Crown prosecutors. Independent Crown prosecutors review the evidence provided and the draft charges, to determine whether any and which charges will be laid. When charges are approved, enforcement officers must present the approved information listing the charges and swear before a Justice as to the veracity of the information. The provincial justice witnesses the officers’ signature, endorses the document and initiates court proceedings. Enforcement officers also prepare summons to be signed by the justice, ordering the accused to appear in court. The officer must also serve the summons to appear on the accused. If the accused opts for a trial by pleading not guilty at first appearance, enforcement officers must provide the required information and assistance to the Crown, with full disclosure to the defence in addition to being available to serve as the primary witness in court.

Enforcement officers must have a significant level of personal commitment to drive the summary conviction process and significant autonomy as their “line manager” (a term sacred in the civil service) is not the Crown prosecutor. The line manager, in the pursuit of justice, must shield enforcement officers from departmental political pressure, so that a farmer residing in the political riding of the Minister of Agriculture is treated the same as farmers not in the Ministers riding. This risk of regulatory capture and politicizing of justice is a frequent criticism where animal protection officers are employed by departments of agriculture [24].

To adapt to the needs of the expanding administrative (non-criminal) federal law, in food safety, environment and agriculture, Agriculture Canada (including CFIA) developed an Administrative Monetary Penalty system (AMPS), [Agriculture and Agri-Food Administrative Monetary Penalties Regulations, SOR/2000-187 [25], (Agriculture and Agri-Food Administrative Monetary Penalties Act SC 1995, c 40)]. The AMPS mimics to some extent the British Common Law summary conviction process, but, outside the provincial court institutions.

In the live receiving at a federal slaughterhouse there is the opportunity to inspect for compliance with the federal humane transportation regulations and discover non-compliance. Inspection for compliance is an inspection where the officer does not expect to find an offence, the discovery of an offence triggers an investigation, which under normal law recruits the human rights protection for the accused. If there are signs of overcrowding at inspection the AMPS process is triggered and the CFIA inspector collects data to support a decision to penalize which remains an inspection for compliance. The decision to assign an AMP results from an investigational review of the information provided in the inspection for compliance. A written Notice of Violation (NOV) is issued to the accused by mail with options for payment. Unlike the CON process, this decision is not made by the primary inspector at the time of discovery, but by a different functionary further up the hierarchy. If the management decision is to penalize, a monetary penalty is calculated using a formula. The accused is notified in writing (NOV) and given the opportunity to agree to the decision and have the fine reduced by 50% by prompt payment. Failure to pay is referred to the Canadian Agricultural Review Tribunal as an appeal.

The AMPS process allows Administrative Agencies to penalize offenders with a monetary penalty significantly larger than the provincial ticketing process allows, but avoids compulsory oversight provided by, review by Crown prosecutors inherent in summary conviction. The summary conviction process by design protects the civil rights and freedoms of the accused as a fundamental requirement of justice and fairness (natural justice). In the arena of federal animal welfare, penalties awarded by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), can be appealed to the Canadian Agriculture Review Tribunal (CART), a legal “court like” organ created by the Act (SC 1995, c 40). Decisions of the CART are appealable to the Federal Court, which is consistent within the framework of British Common Law and natural justice, all convictions have a right of application for appeal.

3. Good Law

In common understanding, a “good” law, articulating a social policy or priority, has the intended purpose to bring about behavioural change in the group of people targeted, resulting in a more just society. Legislatures empower regulators to intervene where there is a public good to achieve and where the individual may have cause to do otherwise. A quality assurance programme for the drafting of regulations has emerged in British Common Law, for this discussion, the “Lon L. Fuller Standard” (LLF-8) [26,27]. The LLF-8 does not address the moral value of any legal instrument, only the inherent quality principles that a law or regulation should conform to. The LLF-8 will be used as the quality standard for this discussion. The LLF-8 is not the only quality construct for evaluating just laws; a European variant holds to four critical dimensions; legal certainty, prevention of misuse of powers, equality before the law, and access to justice [28] which does not in any way conflict with the LLF-8, Table 2.

Table 2.

LLF-8: eight Fuller characteristics of high-quality law and competent lawmaking.

The rule “it is an offence to exceed the posted speed limit” meets the Table 2 quality standard. Speed limits, a socially beneficial proscription, restricting the freedom of action of the individual, is applied to all drivers of vehicles (general), widely promulgated and visible by road signage, directing current and future driver’s behaviour. Speed limits are consistent with all other road safety initiatives, compliance accomplished by decreasing foot pressure on the vehicle throttle control, remaining constant in principle even in school zones and similar special risk zones. The exceptional clarity of this law makes enforcement extremely easy, because an infraction can be objectively and legitimately measured by any one of several technologies including photo-radar systems. It is a scalable, bright line rule, while remaining subordinate to officer discretion, as a serious violation may trigger any process from ticket to criminal indictment. In addition, the licenced driver, the enforcement officer and the courts all see this issue with the same perspective. A good law, it provides a clear method of measuring human behaviour against prohibited behaviour even in the absence of a negative outcome and can ratchet up penalties in proportion to offence severity regardless of specific outcome of the misbehaviour.

Fuller [26] describes law as the “enterprise” of creating and maintaining a functioning society. There is a theory in the development of law that any and all statute development responds to two driving concepts, in varying proportion. The more intuitive driver is identified as prospective–substantive, where the drafters of the law want the machinery of justice to use the law to result in a change in human behaviour increasing societal wellness. The less intuitive driver is identified as political–strategic, where the law is symbolic and does not precipitate changes in human behaviour [29,30]. Symbolic law can be a conscious deception of the public, especially the groups organized and lobbying for the regulation [27]. Law without the promise of enforcement is effectively no law at all, a non-law [26].

There is a rival school of thought that is less critical of symbolic law. This view rests on the ability of law to have norm establishing functions. Law is expressive and communicates a meaning to society [31], a charter of human rights is an example. It is also argued that symbolic law can have a placebo effect in intentionally manipulating public perception to decrease the perception of risk and increase the belief in the law’s effectiveness without a real change in the objective world. An example is the enhanced visibility of airport security post 911, where the increased visibility of airport security did nothing to decrease the real risk of terrorism nor make more effective crime prevention but facilitates the traveller having less anxiety [32]. Other common populist examples include the belief that “tough on crime” laws change human behaviour to make for safer streets [33] and that sex offender registration is protective, because it alters the individuals risk of reoffending. The belief in a positive outcome of these law/policies has no basis in fact [34,35].

Primarily political–strategic laws in animal protection may be common, resulting in no significant real increased protection of animals or measurable relation to offences and prosecution [36]. One can imagine an animal advocacy group campaigning for a particular legal goal such as recognition of animal sentience [37,38] which in the proscriptive-substantive paradigm has no significant impact on the legislative enterprise [39]. In the successful promulgation of ineffective legislation in animal protection, the lobby interests can claim a win (new Law is created) and increase their donations, and the government can claim a win for championing a moral virtue at no real cost to government; even Machiavellian animal use interests that normally oppose methods of production legislation may support a symbolic law.

4. Soft Law

“Soft law” in its simplest form consists of widely accepted norms that have no legal basis. It is a measure of rule by administerial discretion as opposed to court and justice rule [40,41]. No real consensus of descriptive criteria for soft law has yet emerged [28] although it has been previously identified in Canada [42]. Hard law includes statutes, regulations and by-laws issued by regulators of professions and municipal authorities, as these powers are delegated by hard law statutes and articulate a penalty process. Soft law includes just about all the other instruments that are issued by the executive to guide internal decision making, or legitimized by being used by the regulated party, including guidance documents, guidelines, codes, manuals, circulars, directives, bulletins, and other forms [43]. They are usually documents authored by the regulatory authority for use of the regulatory authority and those regulated.

The academic definitions of soft law include two types of characteristics. Firstly, soft law is somewhat defined by what it is not, as some essential elements are missing for soft law to be considered (proper) hard law; however, the close resemblance with hard law is what makes soft law differ from non-law. Rather than cross interrogating the wording, soft law is further defined by looking at the function it performs. Soft law may anticipate hard law (pre-law, as in the evolution of tobacco use restrictions in public), follow the adoption of hard law (post-law interpretive guidelines), or be considered as a substitute to hard law (para-law). In this paper, the Canadian Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada 2001 publication of the recommended Code of Practice for the care and handling of farm animals: Transportation [44] is an exemplar of soft law in Canadian livestock regulation. This document has comprehensive livestock transport maximal crowding limits (Density Charts pp. 36–44). Although claiming to be non-law this unchallenged an unimproved document is featured prominently in defending and prosecuting incidents of livestock loss in transit and may be functioning as para-law, see part 7 below. This application of soft law differentiates the Transport Code from the dozen or so other species specific National Farm Animal Care “care and handling” codes [45].

5. Malleability of Common Law

One of the characteristics of British Common Law is that by design, it follows an evolutionary pattern of continual improvement. As decisions made in specific cases are decided and appealed, they are reviewed in the context of current legal and social norms and become precedents for decisions in future cases. In addition, the law is delivered in the field by policing functionaries with a high degree of knowledge and discretion [46], which anticipates real world variability and smooths jagged law to make it fit for purpose. Although still recognizable, law is often applied in significantly different form than the authors intended [22]. Police or inspector discretion is fundamental to the modern justice creating enterprise [47].

There is no public information to indicate what proportion of NOVs are appealed to the Canada Agriculture Review Tribunal (CART). The 50% reduction in penalty for early payment is a significant design issue to disincentivize appeal. CART decisions are seldom appealed to the Federal Court. A review of NOV for “undue suffering” during transport between 2000 and 2019 identified 159 CART decisions and only 3 related Federal Court of Appeal decisions [48]. Appeals are expensive, success unlikely and out of pocket cost of winning will probably exceed the other choices. The improvement in common law, however, is dependent on appeals and all appeals have public utility. When administrative power is reviewed by the court of appeals, it can effectively modify the law and change significantly how the administrator functions in the future.

In 2009 a CART ruling related to a NOV of causation of unnecessary suffering in transportation of a severely lame pig, was appealed to federal Court (Doyon v. Canada (Attorney General), 2009 FCA 152) [49]. The appellate judge ruled in favour of CART but had further words regarding the administrative monetary penalty system. The Appellate Judge referred to the system as draconian and highly punitive, where in Canadian legal constitutional norms administrative law is prohibited from being punitive. The AMPS punishes diligent individuals, even if they took every reasonable precaution to prevent the commission of the alleged violation. The Act denies individuals who committed a violation the right to make a mistake, even if the mistake could have been made by a reasonable person in the same circumstances. The AMPS encourages the innocent to assume guilt, by granting a 50% discount on the penalty if the penalty is paid quickly. The Judge indicated, at paragraph [28]:

“In short, the Administrative Monetary Penalty System has imported the most punitive elements of penal law while taking care to exclude useful defences and reduce the prosecutor’s burden of proof. Absolute liability, arising from an actus reus which the prosecutor does not have to prove beyond a reasonable doubt, leaves the person who commits a violation very few means of exculpating him- or herself.”

He went on to admonish the administration of the AMPS: at paragraph [29].

“Therefore, the decision-maker must be circumspect in managing and analyzing the evidence and in analyzing the essential elements of the violation and the causal link. This circumspection must be reflected in the decision-maker’s reasons for decision, which must rely on evidence based on facts and not mere conjecture, let alone speculation, hunches, impressions or hearsay.”

6. Methods

The website of the Canadian Agricultural Review Tribunal [50] was searched on using the word “overcrowd*” and the Boolean full text search engine provided by the website, with the time bracket 1 August 2000 to 14 August 2025. The search retrieved 35 results which were downloaded and individually reviewed. Decisions were removed from further consideration where the offence being appealed was not overcrowding but the word overcrowding or overcrowded appeared in the decision. Eight excluded cases were of transporting an unfit animal; inadequate ventilation, exposure to weather, and unfit container (five cases) and there were two written orders unrelated to the appeal process, removing 15 cases.

In the 21 years between 2004 and 2024 there were 20 decisions available for review. The decisions were reviewed by careful reading and compared by length (number of words), whether or not they referred to the 2001 Transportation Code [44], whether the Chairperson used mathematical reasoning in coming to a decision and documented that reasoning in the decision, and the identification of chairperson deciding the file, Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of Tribunal decision.

7. Results

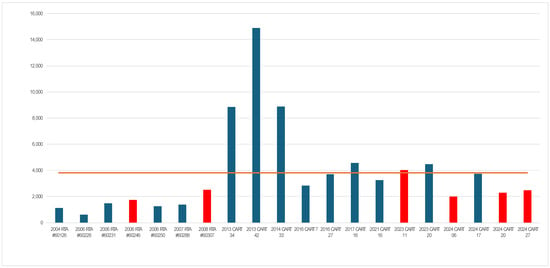

The 20 files of the species consisted of 1 incident of sheep, 3 cattle, 5 chicken, and 11 pig. The CART annual report of outcome in the year 2023–2024 indicates the Tribunal upheld the violation in 13 files and quashed the notice of violation in 1 (7%) [51]. In this 20-year series of adjudicating overcrowding, 30% (6 of 20) were quashed, 3 pig and one each of cattle, chicken and sheep (Table 3, Figure 1). There were 8 authors (Chairperson) creating the final reports with most having 2 or fewer files with the exception of TSP with 7 decisions from 2004 to 2008 and DB with 5 from 2013 to 2017. A priori, number of words in a decision was considered a proxy for the risk of decisions becoming more litigious over time (Figure 1). Word numbers were counted by exporting the pdf files into MS Word and using the word count function. This theory was erroneous as decisions had two parts: (1) Was the offence substantiated? (2) Was the penalty calculated properly? Cases that were quashed did not have text related to confirmation of appropriate penalty.

Figure 1.

Number of words (Y-axis) in each decision (X-axis), red line average word count. The X-axis legend corresponds to the legal case number assigned by the CART appeal process. Of the three apparent outliers in 2013 and 2014, two were written by DB and 2013 CART 42 was the only file authored by BLR. Bars in red indicate the six cases where the notice of violation and monetary penalty were quashed on appeal. Obscured in the image is the 5-year hiatus from 2008 to 2013 when there were no appeals of violations related to overcrowding.

The decisions were read closely in an attempt to identify common features and crucial decisions that have potential to act as precedent in future rulings. The 2001 Transport Code of Practice, [44] although consistently introduced in appeals as non-binding, was referred to in all decisions with the exception of 2016 CART 07, a broiler chicken violation where only one cage was overcrowded. The Transport Code sets limits of maximum pressure in units of mass/area; however, there was no numerical information cited in 9 of 20 decisions (Table 3). The value of science, taking measurements in the real world was challenged in Wendzina, 2007 RTA #60228 (paragraphs not numbered), the Tribunal found:

“The determination as to whether the animals were crowded during transport to such an extent as to be likely to cause injury or undue suffering is not a simple matter of applying the actual weights of the animals and the dimensions of the trailer to the loading density chart (page 4, first paragraph, Wendzina decision)”.And“In determining whether there is overloading to such an extent as to be likely to cause injury or undue suffering, the type, age and condition of the animals at the time of loading, the number of walls in the trailer, the type and extent of floor covering in the trailer and the weather conditions at the time of loading and during transport are all significant factors to be weighed (page 4, third paragraph, Wendzina decision)”.

The Wendzina, 2007 ruling indicates that “overcrowding” in this legal application, in the absence of a specific numerical rule, is somewhat outside of the realm of science and enters the realm of legal and law enforcement judgement. Overcrowding for the practice of the Tribunal is unknown until the Tribunal rules and it becomes a situationally dependent fact. The creation of fact, transformation objective science, the use of measurement in the real world, to a judicial decision was, confirmed by Para 50 of Finley, 2013 CART 42 even in the presence of objective measurement:

“The Tribunal finds that the Agency has established, on the balance of probabilities, that two of the three dead hogs were in compartments of the transport that were overcrowded, based on national code-referenced calculations, considered to provide indica of overcrowding. Overcrowding remains a question of fact, to which various codes or standards may be referred to in support, but which ultimately becomes a determination based on the particular circumstances”.

In this ruling, despite using the soft law standard in making this determination, the Tribunal clearly retains the future option of disregarding the standard under other circumstances. This example suggests reflecting science in legal rulings is difficult if the process values legal rhetoric over repeatable real world measurement.

8. Discussion

This paper reflects on one small institutional arrangement to address a specific cause of avoidable animal suffering in transport, that caused by overcrowding. The behaviour and effectiveness of any enforcement arrangement are difficult areas to critique as review of substantiated welfare violations are rare. Occasionally animal protection investigation records are open to academic review [52].

Overall, from the Tribunal process of review of livestock overcrowding in transport there is limited evidence to believe that the Doyon decision, (at [28]), had a significant or lasting impact on the practice of the Tribunal in reviewing appeals, that of recognition of the significant power imbalance. There is an apparently higher probability of winning an overcrowding appeal than other violations reviewed by CART; 6/20 v. 1/14 [51].

LL Fuller describes law as the “enterprise” of subjecting human conduct to the governance of rules and describes the successful product of science as the ability to predict and control future events. There is a real-world scientific hypothesis of these conditions of maximal safe overcrowding in the units of mass/area. Eschewing the option of including by reference, the Transport Code of Practice and numerical limits seems like an inefficient regulatory choice especially as standards of space allowance for animals by air opts for inclusion by reference.

In the 2020 amendment opportunity, the regulator removed the definitional future looking offence clause, “likely to cause injury or undue suffering”, with focus on the problematic “undue suffering”. The updated Section 148(1) prohibits “loading in a manner that would result in the conveyance or container becoming overcrowded,” which is a weaker future looking rule, necessary as causation is required for culpability and science is firmly focused on identifying ways of predicting the future to avoid things such as undue suffering (48). Future looking offences are created by 148(1)(b) likely to suffer and (c) likely to sustain an injury or die.

In comparing the historic and current overcrowding rules to the LLF-8, does an offence of failure to predict the future ask the impossible of the regulated? The enterprise of science is to understand the nature of reality so as to be able to avoid negative outcomes in the future. In this circular thought, rule 148(1) is theoretically made possible by science, but only if you recruit the wealth of objective knowledge and scientific theory that is open to empirical test and falsification [53].

In a rational prospective science hypothesis, for species that prefer to stand during transportation such as loose horses, there is some level of crowding, if exceeded, a recumbent horse would be unable to regain footing as the remaining horses would close over and prevent efforts of the downer to rise. Similarly, in species that are easily exhausted and prefer to lie down; at some level of crowding, all pigs in a group would be unable to simultaneously lie down without piling on peers. Definition of unlawful overcrowding is 148(1)(a) the animal cannot maintain its preferred position or adjust its body position in order to protect itself from injuries or avoid being crushed or trampled. This description of an offence requires the inspector to make a judgement on the preferences of the group of animals(s) and visible evidence of self-protection. Animal preference is an active and contested field of animal behaviour study, used here as a legally enforceable standard of evidence.

The demands of clarity with what the law prohibits or requires are clearly not met by the current rule. Prohibition of overcrowding with determination based on the particular circumstances cannot be reconciled with the requirement of clarity. The retention of the “likely to” clause in 148(1)(b) and (c) also requires the regulated to see into the future without any officially objective legal guidance. In this application of legal compulsion, is the rule actually compliable? It appears the law is asking the impossible of the regulated. In 2024 CART 27, this future looking aspect of the regulation was directly confronted and the decision read;

“The Agency has not convinced me on a balance of probabilities that it was likely that an animal would suffer, sustain an injury or die due to the number of animals in the container” [Para 34].In this series of appeals there is also evidence of lack of congruence between what written rule declares and how officials enforce the rule. In 2023 CART 20 at para [31]:“While I am sympathetic to Brussels’ concern about the apparent arbitrariness of the Agency’s decision to only investigate when more than three hogs arrive dead in a single load, the Tribunal has no mandate to specify that all breaches of the regulations be enforced.”In 2024 CART 06 at para [39], a similar situation was documented. Inspector Amanda Murphy testified that the regulations in question are “outcome based”. She stated, repeatedly, that the Respondent will not pursue enforcement if an otherwise overcrowded trailer does not show any negative outcomes (like hyperthermia). Inspector Murphy’s testimony is consistent with Section 15.2 of the Respondent’s Interpretive Guidance document.

In operational reality, the enforcement of overcrowding is only initiated where a significant number of animals die. The arbitrary threshold, the size of the pile of dead pigs, communicates to the regulated that, it is death due to overcrowding that is prohibited not overcrowding per se. There is no data available of the frequency of overcrowding on short hauls where stress is not of sufficient temporal duration to result in death of pigs.

The Veterinarian in Charge of the federal slaughter facility is the unfortunate street-level bureaucrat tasked with balancing the resources to inspect and document animal welfare and the resources to inspect and document food safety requirements. On shifts with a staff shortage, it is likely data collection at live receiving may suffer. In Canada, there is no roadside monitoring of livestock compartment floor pressure nor monitoring at assembly points, auction markets or provincial and uninspected abattoirs. The popular practice of comparative evaluation of animal protection of jurisdictions based on statute review only [54] is misleading at best, as it ignores the reality and constraints of street-level enforcement.

CFIA self identifies as Canada’s largest science based regulator [55] yet, eschews numerical thresholds for the definition of an offence of overcrowding in inspection for compliance, yet rely on soft law standards [44] in further adjudication. CFIA was the primary sponsor of the 2001 Transport Code which remains available in electronic format and classified as “archived” under the current management of the National Farm Animal Care Council. There is no intention of reviewing this code in the strategic planning of the Council. The Council considers the CFIA interpretive guidance documents [56] to have replaced a great deal of the Transport Code with the exception of the floor pressure graphs. The CFIA interpretive guidance documents do not provide any numerical violative limits of the mass of live animal per floor area of compartment [56].

The guidance on identifying individual animals unfit to travel Sec 139, [56] is quite extensive, while there are no numerical recommendations on overcrowding. A reasonable explanation for this is that current overcrowding provisions are symbolic legislation, intentionally worded for political not substantive ends. In most critical speculation there may have been no legislative intent to enforce the overcrowding provisions evidenced by making wording very difficult to comply with and difficult to prosecute, in comparison with a numerical threshold. Without being in the room while the decisions are made, it is impossible to judge the intent of the legislature or their advisors. An efficient explanation is that sometime in the 30-year negotiations up to the recent revisions of the regulation it was decided that the issue of overcrowding was unlikely to be successfully negotiated with industry; any possible scientific and easily enforceable definition of overcrowding was traded for other concessions in the regulatory proposal.

The limitations of this study are significant. Public information is only available for the incidents where the accused appealed the penalty. In 2014 CART 33, Western Commercial Carriers Ltd. v. Canada (CFIA), there were 30 DOA pigs on arrival and one additional pig distressed. The appellant believed that a penalty was not justified in the face of 31 dead pigs. This example triggers two major concerns. How frequently do 31 pigs die on a load of 270 pigs and the accused promptly pays the reduced 50% of the calculated penalty and the incident is closed. In prompt penalty payment no public information ever released, and after 5 years the record is expunged. In the structure of the AMPS process, how many pigs does one have to kill to risk being brought before a judge in regular court? The apparent answer is, there is no Health of Animals Regulation offence, so vile that it requires escalation into the normal justice system to achieve justice; the mechanism does not exist.

This second concern can be applied in normal law enforcement. Under The Provincial Offences Act (Manitoba) [57] there are set fines addressing common failure to provide the necessities of life, Sec. 2(1) of the Animal Care Act (Manitoba). For the first offence of failing to provide food and water for a single animal the fine is CAD 298.00 per animal for a maximum of two animals; if your first offence concerns three or more animals or it is a second offence the fine is escalated to CAD 672.00 for animals starved but alive. If, however, the animal dies from neglecting to provide feed or water the fine is CAD 1296.00. The provincial statute articulates suffering leading to death attracts greater financial sanction than suffering survived.

In a Provincial case of severe animal suffering, the enforcement officer has the responsibility to advance the appropriate legal sanction. There is incentive to issue a set fine where available, considering the CON process immediately ends the time commitment of the officer and carries a low risk of review. The summary conviction process on the other hand is a commitment to hundreds of hours of subsequent work. The federal AMP system greatly reduces the risks of public criticism on internal decisions made by government actors tasked with the administration of justice. Animal protection delivered by provincial agriculture employees can mimic this protection of offender privacy by choosing the ticket option over summary conviction for all incidents.

The delivery of justice for the more than human society can be challenging. The question remains of how many animals does a person need to cause to die, to earn an appearance before a judge to answer for their behaviour? In Manitoba, where overwinter cattle starvation is common [58] the set fine standard is silent on more than two animal deaths. This suggests that three animal deaths from starvation would or should trigger a proceeding by summary conviction. Previously in Manitoba in livestock enforcement a 10% death loss from starvation was the criteria to trigger resource commitment to pursue summary conviction [58].

The internal workings of the government, where this paper attempts to peer, are opaque to the common citizen. No outsider is privy to the intent in the creation stages in the regulatory process. The data source used was limited to the transparency window made available by the current Tribunal publication policy. There is no public information to compare the proportion of animal welfare violations in the overall workings of the Tribunal or the fraction of welfare violations that are issued due to overcrowding. There is also no data publicly available to document the proportion of violators that pay half the penalty, regardless of guilt, motivated not by a sense of remorse, but to avoid the cost and inconvenience of the appeal process. In addition to the arbitrary investigation threshold of some number of dead pigs on arrival, of 3(2024, CART 06) there is no assurance that this internal policy is regularly enforced at street-level or how the number of violations would increase with a change in the dead pig pile trigger for investigation. This review would suggest that overcrowding is far more common than is indicated by the evidence available to the public by the Tribunal transparency policy.

A final concern in the decision to adopt an AMPS to address non-compliance is the barriers to escalating the most serious offences to achieve proportional sanction and justice. Most human negligence is not criminal; however, human behaviour includes action that is criminal [59]. This directed reading revealed two incidents were the death loss in transit exceeded 10% of the number of healthy animals loaded, and the offender appealed the Notice of Violation; appeal 2004 RTA60126, 12/115 DOA pigs, and 2014 CART 33, 30/270 pigs. In a related review of CART appeals of the charge of “undue suffering” the author indicated “there are unsettling revelations about what industry and government actors considered to be normal (and therefore tolerable suffering)”, emphasis in original [48].

9. Conclusions

This project was curiosity-driven from the perspective of a previous street-level inspector with 15 years of wrangling animal neglect/abuse cases through the summary convictions process of a Canadian provincial court. Describing the frame within which the federal prohibition of overcrowding in transport is enforced required an introductory description of how general human responsibility for the care of non-human is assured through the court system in Canada. This resulted in a comprehensive narrative of the Canadian animal protection legal system, which has not been described elsewhere. A review of the appeal of federal prohibition of overcrowding in transport revealed structural weaknesses that centre on (1) the lack of consideration for animal welfare in the transportation of livestock and (2) the lack of real transparency in documenting animal protection delivery system.

Future research into this question should use the paradigm of “regulatory failure”, originating in the economics literature, where there is assumed financial interest that benefits from the peculiar dysfunctional arrangement [60]. This document is a strong example of interrogating animal welfare inspection and enforcement in industrial livestock production is a multidisciplinary project.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No ethical approval is required because no live animals are involved.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this manuscript is in the public domain and available from the webpage of The Canadian Agricultural Review Tribunal, https://decisions.cart-crac.gc.ca/cart-crac/en/nav.do, accessed on 1 September 2025.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to Hazel Dalu for careful proofreading and valuable comments on a working draft of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author was responsible for the recommended space allowance recommendations in the 2001 Transport Code of Practice (44) otherwise, the author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- OIE. Appendix 3.7.3 Guidelines for the transport of animals by land. In 2006 OIE Terrestrial Animal Health Code Strasbourg; Office Internationale des Epizooties: Paris, France, 2006; pp. 429–441. [Google Scholar]

- Bench, C.; Schaefer, A.; Faucitano, L. The welfare of pigs during transport. In Welfare of Pigs from Birth to Slaughter; Luigi, F., Schaefer, A.L., Eds.; Wageningen Academic: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 161–195. [Google Scholar]

- CFIA. A History of the Changes to the Transportation of Animals Requirements Under the Health of Animals Regulations (HAR) Part XII; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2024; Available online: https://inspection.canada.ca/en/animal-health/terrestrial-animals/humane-transport/timeline-humane-transport-regulations (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Loly, C.M. The Rise and Fall of the Cattle Train in Canada; University of Manitoba: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 1995; Available online: https://mspace.lib.umanitoba.ca/server/api/core/bitstreams/a1856e73-d091-4e0c-96b8-a862680fd300/content (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Fitzgerald, R.; Stalder, K.; Matthews, J.; Schultz Kaster, C.; Johnson, A. Factors associated with fatigued, injured, and dead pig frequency during transport and lairage at a commercial abattoir. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 87, 1156–1166. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Anna-Johnson-43/publication/23492759_Factors_associated_with_fatigue_injured_and_dead_pig_frequency_during_transport_and_lairage_at_a_commercial_abattoir/links/5492fb5a0cf286fe3121e59f/Factors-associated-with-fatigue-injured-and-dead-pig-frequency-during-transport-and-lairage-at-a-commercial-abattoir.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Doughty, A.; McArthur, D.A. Documents Relating to the Constitutional History of Canada, 1791–1818, Vol. II1914:[xiii]; p. 576. Available online: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_03421 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Britian, G. An Act to Prevent Cruel and Improper Treatment of Cattle and Other Animals, and to Amend the Law Relating to Impounding the Same 1857; pp. 111–119. Available online: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_00925_5 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Canada. The Consolidated Statutes of Canada: Being the Public General Statutes Which Apply to the Whole Province as Revised and Consolidated by the Commissioners Appointed for That Purpose. 1859; [xiii; 32 cm.], p. 1247. Available online: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_08189 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Lower-Canada. An Ordinance for Establishing an Efficient System of Police in the Cities of Quebec and Montreal. Lower Canada The Revised Acts and Ordinances of Lower-Canada. 1845. Available online: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_00928 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Britian, G. The British North America Act, 1867 and Amending Acts. 1867. Available online: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_04236 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Canada. Acts of the Parliament of the Dominion of Canada … Second Session of the Third Parliament, Begun and Holden at Ottawa, on the Fourth Day of February, and Closed by Prorogation on the Eighth Day of April, 1875: Public General Acts: 1875 (pt. 1) (Acts 1–56). 1875. Available online: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_08051_4_1 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Goding, H.; Raub, A.J. The 28 Hour Law Regulating the Interstate Transportation of Live Stock: Its Purpose, Requirements, and Enforcement: US Department of Agriculture. 1918. Available online: https://archive.org/details/28hourlawregulat589godi (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Canada. Acts of the Parliament of the Dominion of Canada, Relating to Criminal Law, to Procedure in Criminal Cases and to Evidence: Compiled from the Revised Statutes of Canada, Which Were … Brought into Force on 1st March, 1887, Under Proclamation Dated 24th January, 1887; with Marginal References to Corresponding Imperial Acts. 1887. Available online: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_02000 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Canada. The Criminal Code: Acts of the Parliament of the Dominion of Canada … Second Session of the Seventh Parliament, Begun and Holden at Ottawa, on the Twenty-Fifth Day of February and Closed by Prorogation on the Ninth Day of July 1892: Public General Acts: 1892 (pt. 1) (Acts 1–29). 1892. Available online: https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.9_08051_21_1 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Canada. Chapter 51 the Criminal Code1954. Available online: https://www.lareau-legal.ca/Martin1955two.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Canada. Bill C-28 An Act to Amend the Animal Contagious Diseases Act. House of Commons Bills, 30th Parliament, 1st Session: C23-C31. [Internet]. 1975; (C-28), pp. 245–286. Available online: https://parl.canadiana.ca/view/oop.HOC_30_1_C23_C31/256 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Canada. Respecting: Bill C-28 An Act to Amend the Animal Contagious Diseases Act. House of Commons Committees, 30th Parliament, 1st Session: Standing Committee on Agriculture, Vol 2 no 36–66. [Internet]. 1975; pp. 1347–1403. Available online: https://parl.canadiana.ca/view/oop.com_HOC_3001_1_2/1347 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- CAPI The Canadian Agri-Food Policy Institute, Ottawa, ON. Analysis of Regulatory and Non-Regulatory Barriers to Domestic Red Meat Trade in Canada. 2022. Available online: https://capi-icpa.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/2022-07-14-Meat-Trade-Report-EN.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Whiting, T.L. Policing farm animal welfare in federated nations: The problem of dual federalism in Canada and the USA. Animals 2013, 3, 1086–1122. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4494357/ (accessed on 1 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, M. Efficacy of Administrative Monetary Penalties in Compelling Compliance with Federal Agri-Food Statutes. LL. D (Doctor of Laws) Thesis, Faculty of Law, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada. 2011. Available online: https://ruor.uottawa.ca/server/api/core/bitstreams/62f93e39-8fb4-4c80-89a1-b1246ee3f8c4/content (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Kantorowicz-Reznichenko, E. Day-fines: Should the rich pay more? Rev. Law Econ. 2015, 11, 481–501. Available online: https://ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/law-n-economics/leb-dam/documents/(2015)%20Day-Fines%20Should%20the%20Rich%20Pay%20More.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- de Winter, P.; Hertogh, M. Public Servants at the Regulatory Front Lines: Street-Level Enforcement in Theory and Practice. In The Palgrave Handbook of the Public Servant; Sullivan, H., Dickinson, H., Henderson, H., Eds.; Palgrave MacMillan: London, UK, 2020; pp. 781–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LSM, 2023 The Law Society of Manitoba, Criminal Procedure, Chapter 1, An Overview of Criminal Procedure. Available online: https://educationcentre.lawsociety.mb.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2020/10/CRIMINAL-PROCEDURE-Ch-1-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Saltelli, A.; Dankel, D.J.; Di Fiore, M.; Holland, N.; Pigeon, M. Science, the endless frontier of regulatory capture. Futures 2022, 135, 102860. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016328721001695 (accessed on 1 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- SOR/2000-187. Available online: https://www.canlii.org/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Fuller, L.L. The Morality of Law (Rev. Ed.); Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, C. Lon Fuller and the moral value of the rule of law. Law Phil. 2005, 24, 239–262. Available online: http://faculty.las.illinois.edu/colleenm/docs/Articles/Murphy-%20Fuller%20and%20the%20Rule%20of%20Law.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Eliantonio, M.; Korkea-aho, E. Soft law and courts: Saviours or saboteurs of the rule of (soft) law? In Research Handbook on Soft Law; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2023; pp. 191–207. Available online: https://cris.maastrichtuniversity.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/192901174/Eliantonio-2023-Soft-law-and-courts.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Bielska-Brodziak, A.; Drapalska-Grochowicz, M.; Suska, M. Symbolic protection of animals. Soc. Regist. 2019, 3, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Klink, B.M.J.; Lembcke, O.W. A Fuller Understanding of Legal Validity and Soft Law. In Legal Validity and Soft Law; Westerman, P., Hage, J., Kirste, S., Mackor, A.R., Eds.; Law and Philosophy Library; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 122, pp. 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunstein, C.R. On the expressive function of law. Univ. Pa. Law Rev. 1996, 144, 2021–2053. Available online: https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3526&context=penn_law_review (accessed on 1 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Aviram, A. The Placebo Effect of Law: Law’s Role in Manipulating Perceptions. Geo. Wash. Law Rev. 2006, 75, 54–150. [Google Scholar]

- Kamin, S. Against a “War on Animal Cruelty” Lessons from the War on Drugs and Mass Incarceration. In Carceral Logics Human Incarceration and Animal Captivity; Lori Gruen, J.M., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson, L. The Sex Offender Registration and Notification Act (SORNA) at 10 years: History, implementation, and the future. Drake Law Rev. 2016, 64, 741–796. [Google Scholar]

- Cubellis, M.A.; Walfield, S.M.; Harris, A.J. Collateral consequences and effectiveness of sex offender registration and notification: Law enforcement perspectives. Int. J. Offender Ther. Comp. Criminol. 2018, 62, 1080–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suska, M. Becoming Symbolic: Some Remarks on the Judicial Rewriting of the Offence of Animal Abuse in Poland. Int. J. Semiot. Law-Rev. Int. Sémiotique Jurid. 2024, 38, 1271–1289. Available online: https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s11196-024-10204-5.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Park, J. Yes, Chickens Have Feelings Too. The Recognition of Animals Sentience Will Address Outdated Animal Protection Laws for Chickens and Other Poultry in the United States. San Diego Int. Law J. 2020, 22, 335–364. Available online: https://digital.sandiego.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1318&context=ilj (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Landi, M.; Anestidou, L. Animal Sentience Should Be the Key For Future Legislation. Anim. Law 2024, 30, 257–273. Available online: https://lawcommons.lclark.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1451&context=alr (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Lessard, M. Can Sentence Recognition Protect Animals? Lessons from Quebec’s Animal Law Reform. Anim. Law 2021, 27, 57. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, N. Soft law: An historical introduction. In Research Handbook on Soft Law; Edward Elgar Publishing: Camberley, UK, 2023; pp. 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Robilant, A.D. Genealogies of soft law. Am. J. Comp. Law 2006, 54, 499–554. Available online: https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship/2900 (accessed on 1 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Sossin, L.; Van Wiltenburg, C. The puzzle of soft law. Osgoode Hall Law J. 2021, 58, 623–668. Available online: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3713&context=ohlj (accessed on 1 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- CFIA. Regulatory Guidance and Resources for the Humane Transport of Animals; Canadian Food Inspection Agency: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2025; Available online: https://inspection.canada.ca/en/animal-health/terrestrial-animals/humane-transport/guidance-and-resources (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- CARC; CFHS. Recommended Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Farm Animals Transportation; Canadian Agri-Food Research Council: Nepean, ON, Canada, 2001; Available online: https://www.nfacc.ca/pdfs/codes/transport_code_of_practice.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Sankoff, P. Canada’s experiment with industry self-regulation in agriculture: Radical innovation or means of insulation. Can. J. Comp. Contemp. Law 2019, 5, 299–348. Available online: https://www.cjccl.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Sankoff.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Hassan, M.S.; Al Halbusi, H.; Ahmad, A.B.; Abdelfattah, F.; Thamir, Z.; Raja Ariffin, R.N. Discretion and its effects: Analyzing the role of street-level bureaucrats’ enforcement styles. Int. Rev. Public Adm. 2023, 28, 480–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronitt, S.H.; Stenning, P. Understanding discretion in modern policing. Crim. Law J. 2011, 35, 319–332. Available online: https://constitutionwatch.com.au/wp-content/uploads/POLICE-DISCRETION.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Sniderman, A.S. “Clearly a Subjective Determination”: Interpretations of “Undue Suffering” at the Canada Agricultural Review Tribunal (2000–2019). Ott. Law Rev. 2021, 53, 437–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letourneau, J. Doyon v. Canada (Attorney General), 2009 FCA 1522009; A-513-08. Available online: https://canlii.ca/t/26kcr (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- CART. Decisions Ottawa, ON: Canada Agriculture Review Tribunal 2025 [Searchable Website]. Available online: https://decisions.cart-crac.gc.ca/cart-crac/en/ann.do (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- CART. Canada Agricultural Review Tribunal Annual Report 2023–2024, CART-CRAC: Canada Agricultural Review Tribunal. Canada. Available online: https://coilink.org/20.500.12592/yzkymvx (accessed on 18 August 2025).

- Williams, N.; Hemsworth, L.; Chaplin, S.; Shephard, R.; Fisher, A. Analysis of substantiated welfare investigations in extensive farming systems in Victoria, Australia. Aust. Vet. J. 2024, 102, 440–452. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1111/avj.13342 (accessed on 1 September 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popper, K.R. Science as falsification. Conjectures Refutations 1963, 1, 33–39. Available online: https://www.kth.se/social/files/57da705ef276540c0f789308/KPopper_Falsification.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- WSPA. Animal Protection Index—Interactive Data Map; World Animal Protection, formerly The World Society for the Protection of Animals (WSPA): London, UK, 2025; Available online: https://api.worldanimalprotection.org/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- CFIA. News Release Canada’s Largest Science-Based Regulator Marks 25 Years of Protecting Food, Plants and Animals, 2022. 2025-05-06. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/food-inspection-agency/news/2022/04/canadas-largest-science-based-regulator-marks-25-years-of-protecting-food-plants-and-animals.html (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- CFIA. Health of Animals Regulations: Part XII: Transport of Animals-Regulatory Amendment—Interpretive Guidance for Regulated Parties; Canadian Food Inspection Agency: Ottawa ON, Canada, 2025; Available online: https://inspection.canada.ca/en/animal-health/terrestrial-animals/humane-transport/health-animals-regulations-part-xii (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Manitoba The Provincial Offences Act, C.C.S.M. c. P160, Preset Fines and Offence Descriptions Regulation, M.R. 96/2017, Schedule, A. Available online: https://web2.gov.mb.ca/laws/regs/current/forms/096_2017/sched_ae.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Whiting, T.L.; Postey, R.C.; Chestley, S.T.; Wruck, G.C. Explanatory model of cattle death by starvation in Manitoba: Forensic evaluation. Can. Vet. J. 2012, 53, 1173–1180. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3474572/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Fletcher, G.P. Theory of criminal negligence: A comparative analysis. Univ. Pa. Law Rev. 1970, 119, 401–438. Available online: https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5814&context=penn_law_review (accessed on 1 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J. Regulation and failure. In New Perspectives on Regulation; David, M., John, C., Eds.; The Tobin Project: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009; Ch. 1; pp. 11–23. Available online: https://libros.metabiblioteca.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/b5c6b2cb-b6ae-4919-b5d6-b332b26e7ff4/content#page=11 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).