Natural Savanna Systems Within the “One Health and One Welfare” Approach: Part 2—Sociodemographic and Institution Factors Impacting Relationships Between Farmers and Livestock

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Considerations

2.2. General Description

2.3. Quantitative Study

2.3.1. Structured Survey and Sampling

2.3.2. Data Analysis—Quantitative Study

2.4. Qualitative Study (Focus Groups and Interviews)

Data Analysis—Qualitative Study

2.5. Positionality and Reflexivity Statement

2.6. Data Presentation

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

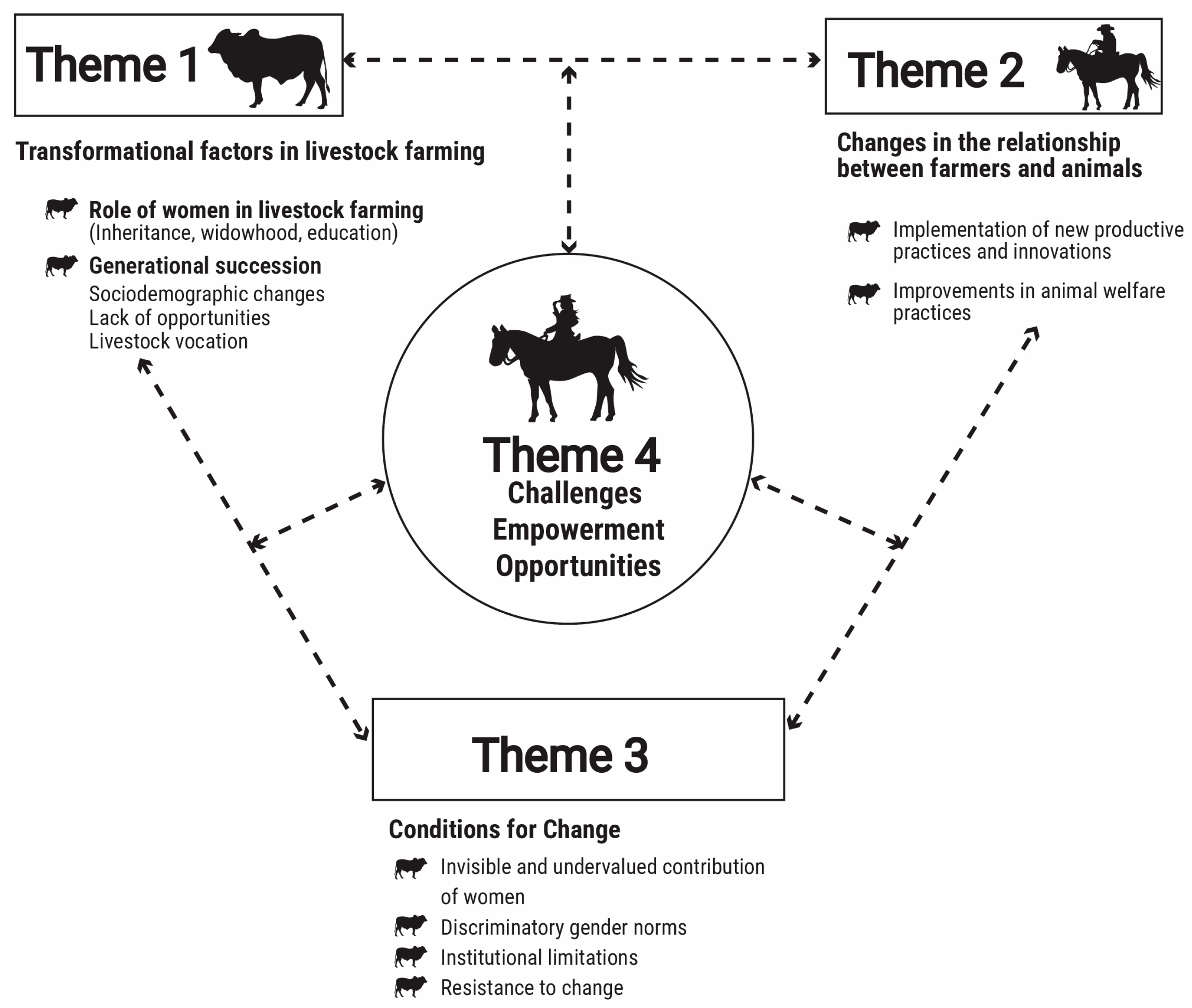

3.2. Key Themes Identified

3.2.1. Theme 1: Transformational Factors in Livestock Farming

- a.

- Changing Role of Women in Livestock Farming

- b.

- Lack of Generational Succession

3.2.2. Theme 2: Changes in the Relationship Between Farmers and Animals

- Implementation of New Productive Practices and Innovations

- b.

- Improvements in Animal Welfare Practices

3.2.3. Theme 3: Conditions for Change

- Invisible and Undervalued Contribution of Women

- b.

- Discriminatory Gender Norms

- c.

- Low Income and Limited Access to Financing

- d.

- Institutional Limitations

- e.

- Resistance to Change

3.2.4. Theme 4: Challenges and Opportunities for Improvement

- Empowerment of Women and Rural Youth

- b.

- Integrative Pedagogical Methodologies

- c.

- Access and Marketing Logistics

- d.

- Responsible Governance

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rye, J.F. Rural Youths’ Images of the Rural. J. Rural Stud. 2006, 22, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Rios, L.A.; Vargas-Villegas, J.; Suarez, A. Local Perceptions about Rural Abandonment Drivers in the Colombian Coffee Region: Insights from the City of Manizales. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Reyes, P.; Wiig, H. Reasons of Gender. Gender, Household Composition and Land Restitution Process in Colombia. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 75, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triana Ángel, N.; Burkart, S. Youth in Livestock and the Power of Education: The Case of “Heirs of Tradition” from Colombia, 2012–2020. J. Rural Stud. 2023, 97, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losada-Espinosa, N.; Miranda-De la Lama, G.C.; Estévez-Moreno, L.X. Stockpeople and Animal Welfare: Compatibilities, Contradictions, and Unresolved Ethical Dilemmas. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2020, 33, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, P.A.; Varnum, A.; Bigler, L.; Cramer, M.C.; Román-Muñiz, I.N.; Edwards-Callaway, L.N. Driving Change: Exploring Cattle Transporters’ Perspectives to Improve Worker and Animal Well-Being. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2025, 9, txaf021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, M.H.; Gallego-Polania, S.A.; Sanchez, J.A. Natural Savannah Systems Within the “One Welfare” Approach: Part 1—Good Farmers’ Perspectives, Environmental Challenges and Opportunities. Animals 2025, 15, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rault, J.-L.; Waiblinger, S.; Boivin, X.; Hemsworth, P. The Power of a Positive Human–Animal Relationship for Animal Welfare. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 590867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leon, A.; Sanchez, J.; Romero, M. Association between Attitude and Empathy with the Quality of Human-Livestock Interactions. Animals 2020, 10, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, R.J.F. Understanding Farmers’ Aesthetic Preference for Tidy Agricultural Landscapes: A Bourdieusian Perspective. Landsc. Res. 2012, 37, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaujouan, J.; Cromer, D.; Boivin, X. Review: From Human–Animal Relation Practice Research to the Development of the Livestock Farmer’s Activity: An Ergonomics–Applied Ethology Interaction. Animal 2021, 15, 100395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaarst, M.; Ritter, C.; Saraceni, J.; Roche, S.; Wynands, E.; Kelton, D.; Koralesky, K.E. Invited Review: Qualitative Social and Human Science Research Focusing on Actors in and around Dairy Farming. J. Dairy Sci. 2024, 107, 10050–10065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daigle, C.L.; Ridge, E.E. Investing in Stockpeople Is an Investment in Animal Welfare and Agricultural Sustainability. Anim. Front. 2018, 8, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontanilla-Díaz, C.A.; Preckel, P.V.; Lowenberg-DeBoer, J.; Sanders, J.; Peña-Lévano, L.M. Identifying Profitable Activities on the Frontier: The Altillanura of Colombia. Agric. Syst. 2021, 192, 103199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, H.; Balmford, A.; Holmes, M.A.; Wood, J.L.N. Advancing the Quantitative Characterization of Farm Animal Welfare. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2023, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD Income Inequality. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/income-inequality.html (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Gobierno Departamental del Vichada. Plan Departamental de Desarrollo Trabajo Para Todo Vichada 2020–2023; Gobierno Departamental del Vichada: Vichada, Colombia, 2020; p. 368. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp Stata Statistical Software; Version 15. StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2025.

- Ritter, C.; Koralesky, K.E.; Saraceni, J.; Roche, S.; Vaarst, M.; Kelton, D. Invited Review: Qualitative Research in Dairy Science—A Narrative Review. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 5880–5895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johanssen, J.R.E.; Kvam, G.-T.; Logstein, B.; Vaarst, M. Interrelationships between Cows, Calves, and Humans in Cow-Calf Contact Systems—An Interview Study among Norwegian Dairy Farmers. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 6325–6341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhawana, K.; Race, D. Women’s Approach to Farming in the Context of Feminization of Agriculture: A Case Study from the Middle Hills of Nepal. World Dev. Perspect. 2020, 20, 100260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottet, A.; Bicksler, A.; Lucantoni, D.; De Rosa, F.; Scherf, B.; Scopel, E.; López-Ridaura, S.; Gemmil-Herren, B.; Bezner Kerr, R.; Sourisseau, J.-M.; et al. Assessing Transitions to Sustainable Agricultural and Food Systems: A Tool for Agroecology Performance Evaluation (TAPE). Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 579154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unay-Gailhard, İ.; Bojnec, Š. Gender and the Environmental Concerns of Young Farmers: Do Young Women Farmers Make a Difference on Family Farms? J. Rural Stud. 2021, 88, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavenner, K.; Crane, T.A. Gender Power in Kenyan Dairy: Cows, Commodities, and Commercialization. Agric. Hum. Values 2018, 35, 701–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijers, G.D.M. Inequality Regimes in Indonesian Dairy Cooperatives: Understanding Institutional Barriers to Gender Equality. Agric. Hum. Values 2019, 36, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohmwirth, C.; Hanisch, M. Women’s Active Participation and Gender Homogeneity: Evidence from the South Indian Dairy Cooperative Sector. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 72, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enticott, G.; O’Mahony, K.; Shortall, O.; Sutherland, L.-A. ‘Natural Born Carers’? Reconstituting Gender Identity in the Labour of Calf Care. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 95, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, K.; Thompson-Colón, T.; Bastidas-Granja, A.M.; Del Castillo Matamoros, S.E.; Olaya, E.; Melgar-Quiñonez, H. Women’s Autonomy and Food Security: Connecting the Dots from the Perspective of Indigenous Women in Rural Colombia. SSM-Qual. Res. Health 2022, 2, 100078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valerio, E.; Hilmiati, N.; Stella Thei, R.; Safa Barraza, A.; Prior, J. Innovation for Whom? The Case of Women in Cattle Farming in Nusa Tenggara Barat, Indonesia. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 106, 103198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badstue, L.; Elias, M.; Kommerell, V.; Petesch, P.; Prain, G.; Pyburn, R.; Umantseva, A. Making Room for Manoeuvre: Addressing Gender Norms to Strengthen the Enabling Environment for Agricultural Innovation. Dev. Pract. 2020, 30, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farnworth, C.R.; Jafry, T.; Lama, K.; Nepali, S.C.; Badstue, L.B. From Working in the Wheat Field to Managing Wheat: Women Innovators in Nepal. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2019, 31, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, S.; Edvardsson, K.; Fisher, C.; Spelten, E. Perceptions and Interpretation of Contemporary Masculinities in Western Culture: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Men’s Health 2021, 15, 15579883211061009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glazebrook, T.; Noll, S.; Opoku, E. Gender Matters: Climate Change, Gender Bias, and Women’s Farming in the Global South and North. Agriculture 2020, 10, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe. In Familias y Políticas Públicas En América Latina: Una Historia de Desencuentros; CEPAL: Santiago, Chile, 2007; Available online: https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/2504-familias-politicas-publicas-america-latina-historia-desencuentros (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Rahman, M.M.; Huq, H.; Hossen, M.A. Patriarchal Challenges for Women Empowerment in Neoliberal Agricultural Development: A Study in Northwestern Bangladesh. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anneberg, I.; Sandøe, P. When the Working Environment Is Bad, You Take It out on the Animals—How Employees on Danish Farms Perceive Animal Welfare. Food Ethics 2019, 4, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Torres, J.A.; Reina-Rozo, J.D. Agroecology and Communal Innovation: LabCampesino, a Pedagogical Experience from the Rural Youth in Sumapaz Colombia. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2022, 4, 100162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, K.P.; Pagot, R.; Prá, J.R. Sustainable Development Goal 5: Women’s Political Participation in South America. World Dev. Sustain. 2024, 4, 100138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Campo, M.; Montossi, F.; Soares de Lima, J.M.; Brito, G. Future Cattle Production: Animal Welfare as a Critical Component of Sustainability and Beef Quality, a South American Perspective. Meat Sci. 2025, 219, 109672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampton, J.O.; Jones, B.; McGreevy, P.D. Social License and Animal Welfare: Developments from the Past Decade in Australia. Animals 2020, 10, 2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, M.H.; Uribe-Velásquez, L.F.; Sánchez, J.A.; Rayas-Amor, A.A.; Miranda-de la Lama, G.C. Conventional versus Modern Abattoirs in Colombia: Impacts on Welfare Indicators and Risk Factors for High Muscle PH in Commercial Zebu Young Bulls. Meat Sci. 2017, 123, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, M.H.; Uribe-Velásquez, L.F.; Sánchez, J.A.; Miranda-de la Lama, G.C. Risk Factors Influencing Bruising and High Muscle PH in Colombian Cattle Carcasses Due to Transport and Pre-Slaughter Operations. Meat Sci. 2013, 95, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gagaoua, M.; Gondret, F.; Lebret, B. Towards a ‘One Quality’ Approach of Pork: A Perspective on the Challenges and Opportunities in the Context of the Farm-to-Fork Continuum—Invited Review. Meat Sci. 2025, 226, 109834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandin, T. Grazing Cattle, Sheep, and Goats Are Important Parts of a Sustainable Agricultural Future. Animals 2022, 12, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parodi, A.; Valencia-Salazar, S.; Loboguerrero, A.M.; Martínez-Barón, D.; Murgueitio, E.; Vázquez-Rowe, I. The Sustainable Transformation of the Colombian Cattle Sector: Assessing Its Circularity. PLOS Clim. 2022, 1, e0000074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minagricultura Resolución 000253 Del 2020. Available online: https://www.minagricultura.gov.co/Normatividad/Resoluciones/RESOLUCI%C3%93N%20NO.%20000253%20DE%202020.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- ICA Resolución, No.00016409. Available online: https://www.ica.gov.co/getattachment/Areas/Pecuaria/Servicios/Inocuidad-en-las-Cadenas-Agroalimentarias/Bienestar-Animal/Res-00016409-de-2024-BA.pdf.aspx?lang=es-CO (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Ministerio de Transporte & ICA Resolución 20223040006915 de 2022 Ministerio de Transporte—Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario—ICA. Available online: https://www.ica.gov.co/getattachment/ab7e54ab-28a0-4c58-9a86-8ecc49fea4a9/2022R3040006915.aspx (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social Resolución 240. Available online: www.minsalud.gov.co/Normatividad_Nuevo/Resolución%200240%20de%202013.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Balzani, A.; Hanlon, A. Factors That Influence Farmers’ Views on Farm Animal Welfare: A Semi-Systematic Review and Thematic Analysis. Animals 2020, 10, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, K.; Sjöström, K.; Stiernström, A.; Emanuelson, U. Dairy Farmers’ Perspectives on Antibiotic Use: A Qualitative Study. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 2724–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICA Resolución 1634 de 2010. Available online: https://www.ica.gov.co/getattachment/5696cea4-3be2-4874-ae2d-302e32cf6dc7/2010R1634.aspx (accessed on 4 August 2024).

| Characteristics | Survey n (%) | Interviews n (%) | Focal Groups n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 59(90.8) | 10(90.9) | 14(58) |

| Female | 6(9.2) | 1(9.1) | 10(42) | |

| Age | 22–32 | 2(3.1) | 1(9.1) | 1(4.2) |

| 33–43 | 12(18.6) | 3(27.3) | 9(37) | |

| 44–54 | 24(36.8) | 4(36.3) | 6(25.2) | |

| 55–65 | 21(32.2) | 3(27.3) | 5(21) | |

| 66–76 | 6(9.3) | “_” | 3(12.6) | |

| Level of education | No education | 10(15.5) | “_” | 4(16.8) |

| Primary | 45(68.9) | 2(18.2) | 10(42) | |

| Secondary | 9(13.9) | 1(9.1) | 4(16) | |

| Post-secondary | 1(1.7) | 8(72,1) | 6(25.2) | |

| Years of experience | 8–18 | 9(13.9) | 1(9,1) | “_” |

| 19–29 | 10(15.3) | 5(45.4) | 1(4) | |

| 30–40 | 30(45,2) | 4(36.4) | 13(54) | |

| 41–51 | 14(22.4) | “_” | 5(21) | |

| 52–62 | 2(3.2) | 1(9.1) | 5(21) | |

| Topics and Subtopics | Quotes That Reflect the Subtopic | Quantitative Results That Support the Subtopic |

|---|---|---|

| Subtopic 1: Gender Cultural Transitions | ||

| a. Change in the role of women in livestock farming due to inheritance and widowhood | [P5_GR2M]: “... My link to livestock also comes from family, from inheritance... over time, you see how your father manages the cattle... or you go to work in the plains, and you grow fond of livestock.” | Quantitative: 90.8% of farms are managed by men (n = 59), 9.2% by women (n = 6) |

| b. Widowhood | [P11_GR2M]: “When my husband died and I was left with the farm, everyone told me: sell it! Because you’re a woman... but I said to myself: how can I not be capable... and I took over the farm.” | Quantitative: 95% married producers (n = 62), 5% single or widowed (n = 3) |

| c. Access to education | [P7_GR2M]: “They taught me from a young age to be passionate about livestock. I studied at university... I’m an agribusiness and livestock manager.” | Livestock producers have begun pursuing post-secondary education (Table 1) |

| Subtopic 2: Lack of Generational Replacement | ||

| a. Sociodemographic changes | [P30_GR1H]: “The older people are dying out, and even if they say my father and grandfather were farmers, the reality is the activity is being abandoned...”. | Age range of farmers: 22–43 (18.5%), 44–54 (36.9%), 55–65 (32.3%), 66–76 (9.2%) |

| b. Lack of opportunities for young people in rural areas | [P28_GR3]: “This is another problem. Young people study but don’t want to return to the plains because there are no job opportunities.” | Only 3.1% (n = 2) of farmers are between 22 and 32 years old |

| c. Access to education | [P122_INTERH] “…Schools are a long way from farms. Parents send their children to schools for a week or two so they can study.” | Low education level (Table 1) |

| d. Livestock | [P119_INTERH] “Traditional farmers love this lifestyle but would live better with more government support—and that’s not happening.” [P120_INTERH] “… Ranching is a job that requires a lot of sacrifice, specially working in in the fields, because you get up very early, and have to do a lot, and return exhausted and have a little time to be with the family…” | 93.8% (n = 61) consider livestock farming important for society |

| The song of the plains | [P17_GR1H]: “The cattle driving song is a part of culture and it must be protected. One thing is the song during milking, and another is the song so that the cattle calms down.” | 93.8% (n = 61) consider livestock farming important for society |

| Subtopics | Quotes That Reflect the Subtopic | Quantitative Results That Support the Subtopic |

|---|---|---|

| a. Implementation of new production practices and innovations | [P28_INTERH] “There have been changes. Due to this generational shift, my father managed everything extensively, and now that I’m a veterinarian, I bring a different perspective—not only focused on the economy but also considering social, environmental, cultural, and political aspects.” [P36_GR2M]: “Today, women are taken into account more, because before we weren’t seen at all—only men [...] now I manage the farm, and I haven’t let it decline.” | |

| b. Adoption of innovations | [P6_GR3I]: “Those who propose big changes are not locals, they are outsiders who motivate producers to improve and adopt new practices and technologies like artificial insemination, pasture management, and more.” | A total of 18.5% (n = 12) of farmers associate changes with adopting new technologies for animal management and 32.3% (n = 21) with changes in production culture. |

| c. Improvement in animal welfare practices | [P65_INTERH]: “My mother handled milking and taming the cows; my father only helped when the cow was aggressive or hard to milk. Generally, taming is done by women—they’re gentle, they care…” [P108_INTERH]: “When you herd cattle, the way you whistle or shout at them affects their behavior. It’s easier to handle cattle used to humans, especially if treated well—it creates a special connection. Poor handling leads to aggressive animals, because poor handling has consequences.” | Among female farm administrators (n = 17), 72.3% carry out cattle herding and household management activities. |

| Subtopics | Quotes That Reflect the Subtopic | Quantitative Results That Support the Subtopic |

|---|---|---|

| a. Invisible and undervalued contribution of women | [P71_INTERH]: “After milking, women do household chores, cook for the family and workers, clean the house, take care of the children, handle backyard animals (chickens, pigs, sheep), and care for the garden.” | A total of 67.7% (n = 44) of women receive no income, 23.1% (n = 15) earn between 0.5 and 1 minimum wage, 6.2% (n = 4) earn 1–2 minimum wages, and 3% (n = 1) earn over 2 minimum wages. |

| b. Discriminatory gender norms | [P8_GR2M]: “One day my dad mistreated my mom saying: ‘You’re a woman, and women belong in the kitchen.’ I told him: ‘No, dad, women are just as important—ranching is not a gender issue, it’s about love and administrative skill, which we women have!’” [P30_GR3]: “Gender issues evolve culturally. Llaneros think women belong in the kitchen and home. But this has been changing somewhat with more education and training opportunities for women.” | A total of 90.8% (n = 59) of farms are managed by men and 9.2% (n = 6) by women. |

| c. Lack of institutional recognition | [P40_GR2W]: “I would like to see institutions offering training and guidance for women and they should call us together […], women are very conscientious, hard-working, and we like to learn.” | |

| d. Low income and poor access to financing | [P19_GR3]: “Another problem is financial—adopting changes and technology is expensive. A proper corral with chute costs a lot. I told my brother to build one, and he said he’d have to sell a cow, which would leave him with nothing.” | A total of 52.3% (n = 34) have no formal employment link, 12.3% (n = 8) have formal contracts (written), and 35.4% (n = 23) have verbal contracts. A total of 46.1% (n = 30) have no income other than ranching, 47.7% (n = 31) have income from agriculture or commissions, and 6.2% (n = 4) have income from general services. Reasons for insufficient income: 52.3% (n = 34) high cost of living, 15.4% (n = 10) low salary, 32.3% (n = 21) other cost-of-living issues. |

| [P112_INTERH] “Credit for farmerss is limited, aimed only at those who meet bank requirements. There’s been no real government support for projects, infrastructure, or machinery, so everyone works individually—no incentives.” | A total of 66.2% (n = 43) have never accessed bank credit, while 33.8% (n = 22) have accessed it at least once. | |

| e. Institutions’ basic sanitation | [P110_Int] “…Ranching is seen as a second or third-class activity. Being an ‘agro worker’ still seems very rustic and primitive.” [P123_INTERH] “Without electricity, we’re nothing. If the state really invested in this, the region would thrive. Go to Puerto Carreño—people don’t even have electricity.” | A total of 6.9% (n = 11) have no electricity, 81.5% (n = 53) use solar energy, and 1.5% (n = 1) use a solar + gasoline generator. Potable water source: 64.6% (n = 42) from deep wells, 13% (n = 20) from natural springs, 15.4% (n = 10) from streams. Cooking energy source: 60% (n = 39) firewood, 30.8% (n = 20) gas + firewood, 9.2% (n = 6) only natural gas. Waste disposal: 56.9% (n = 37) use toilets with septic tanks, 41.6% (n = 27) have more than one toilet, 1.5% (n = 1) defecate in the open. |

| f. Information and communication technology ICT | [P118_INTERH] “Internet signal is very poor in some regions.” | A total of 78.5% (n = 51) have mobile phones, 12.3% (n = 8) have access to radio/TV/internet, and 9.2% (n = 6) have no access. |

| g. Infrastructure—lack of roads | [P33_GR1H]: “…What’s the point of raising well-kept cattle with shade and water if, when transporting them inland, we lose everything due to bad roads. Without proper access, all the effort is lost.” | No local slaughterhouses in the region, 100% (n = 65) do not sell cattle by scale, 86.2% (n = 56) have wooden corrals, 9.2% (n = 6) have cement corrals, and 4.6% (n = 3) have none. |

| [P5_GR1M]: “It’s a struggle to move animals—even loading them is hard without proper docks—we feel bad and so do the animals. We don’t get state licenses to unload them. It’s a horrible—for us and for the animals, and it generates a lot of cost” | A total of 92.3% (n = 60) of farms do not have a cattle handling pen. | |

| h. Security | [P117_INTERH] “We’re at the mercy of cattle theft and no one helps. The state doesn’t intervene. Even when thieves are caught, they’re not prosecuted. There’s no peace or security anymore, everything is affected by insecurity...” | Security perception: 15.4% (n = 10) good, 49.2% (n = 32) regular, 35.4% (n = 23) bad. A total of 100% (n = 65) report the main security issues as cattle theft and extortion. |

| i. Resistance to change | [P4_GR3I]: “I’m a Llanero (Farmer) and I know change is needed, but to what extent does new technology strip us of our essence? Institutions should respect and consider our identity...” | The importance of livestock activity for farmers is based on 32.3% (n = 21) keeping the plains tradition alive, 58.5% (n = 38) on local economic development, 3.1% (n = 2) on food production, and 6.1% (n = 4) on the generation of new knowledge. |

| [P3_GR1H] “For me, it’s a complex issue because right now we have to apply many vaccines each year, and the government requires them—three a year—but we have to apply two more. [...] We know that we have to take care of livestock; so I don’t know how to interpret animal welfare. That’s like a contradiction.” [P124_INTERH] “...Traditional livestock farmers vaccinate because they have the authority pressuring them, or else they wouldn’t vaccinate [...] Institutions have not been able to get livestock farmers to integrate into their knowledge the usefulness of vaccination for controlling officially controlled diseases.” |

| Subtopics | Quotes That Reflect the Subtopic | Quantitative Results That Support the Subtopic |

|---|---|---|

| Empowerment of women and rural youths | [P27_GR3] “As for gender policies, these require public institutions to hire women, but on the other hand, today there are women in the region who are highly qualified academically and have experience, so it’s no longer necessary to hire them from other departments...” | A total of 100% (n = 65) of the livestock farmers report that the main credit institution is the Agricultural Bank. |

| [P37_GR2M]: “I think it would be important to include young people in the new changes, because we need to integrate them more so they fall in love with the livestock culture. We should invite our children to participate.” | ||

| [P115_INTERH] “... Credit, which is the only option a farmer has, apart from his capital, selling cows to acquire technology, is not possible because it would diminish his working capital...” | ||

| Integrative pedagogical methodologies | [P30_GR3]: “… I think life in the plains has changed somewhat as there are more opportunities for education and training for women and young people. So I think what we need to achieve are more mechanisms so that people can get an education, so that they can get training, and develop.” | A total of 1.5% (n = 1) of the farmers acquire their knowledge through formal education, 98.5% (n = 64) through tradition and the exchange of knowledge. |

| [P1_INTERM] “As I’m a veterinarian, if there’s any problem with the animals, I go and examine them; if any procedure needs to be performed, it’s done. With vaccinations, we also have to make sure both cycles are completed.” | ||

| Access routes and commercialization | [P116_INTERH] “… the conditions of the roads and pathways are very poor. If you produce very good livestock, you don’t have the conditions to market them, because unfortunately, there’s no support from the national government for the countryside, in terms of roads and communications…” [P14_GR3I]: “I believe that the change in livestock transportation has been improving; we’ve gone from transporting them by river to transporting them by land [...]. Previously, there were no bridges, and livestock had to be swum across the river, and that was a risk for the animals, for the plainsmen, and the horses. Now we have some bridges, but many roads are still missing, and transport times are very long.” | There are two slaughterhouses for domestic consumption in the department. During the summer, cattle are transported on foot and by road by truck and during the winter, on foot or by boat on the river. Fifty percent (n = 2) of the municipalities in the department of Vichada have a slaughterhouse for domestic consumption. One hundred percent (n = 65) of the access roads to the farms are unpaved. |

| Governance | [P34_GR3]: “…When social security breaks down, it affects investment, and if there’s no investment, there’s no employment, no doctor, and then you have to go out to the city for just about anything, and that complicates your life. So the lack of security does us a lot of harm [...] and thus, backwardness develops in the region and the quality of life of the residents weakens.” [P29_GR3]: “For me, there’s no institutional coordination, because each one has its own guidelines and they don’t work in an integrated manner. Coordination between the public and private sectors would be very important to provide better services, foster partnerships, and have the support of veterinarians.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Romero, M.H.; Gallego-Polania, S.A.; Sanchez, J.A. Natural Savanna Systems Within the “One Health and One Welfare” Approach: Part 2—Sociodemographic and Institution Factors Impacting Relationships Between Farmers and Livestock. Animals 2025, 15, 2139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15142139

Romero MH, Gallego-Polania SA, Sanchez JA. Natural Savanna Systems Within the “One Health and One Welfare” Approach: Part 2—Sociodemographic and Institution Factors Impacting Relationships Between Farmers and Livestock. Animals. 2025; 15(14):2139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15142139

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomero, Marlyn H., Sergio A. Gallego-Polania, and Jorge A. Sanchez. 2025. "Natural Savanna Systems Within the “One Health and One Welfare” Approach: Part 2—Sociodemographic and Institution Factors Impacting Relationships Between Farmers and Livestock" Animals 15, no. 14: 2139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15142139

APA StyleRomero, M. H., Gallego-Polania, S. A., & Sanchez, J. A. (2025). Natural Savanna Systems Within the “One Health and One Welfare” Approach: Part 2—Sociodemographic and Institution Factors Impacting Relationships Between Farmers and Livestock. Animals, 15(14), 2139. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15142139