Hierarchy-Dependent Behaviour of Dogs in the Strange Situation Test: High-Ranking Dogs Show Less Stress and Behave Less Friendly with a Stranger in the Presence of Their Owner

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

Hypotheses and Predictions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dog Participants

2.2. Questionnaire

2.3. Strange Situation Test

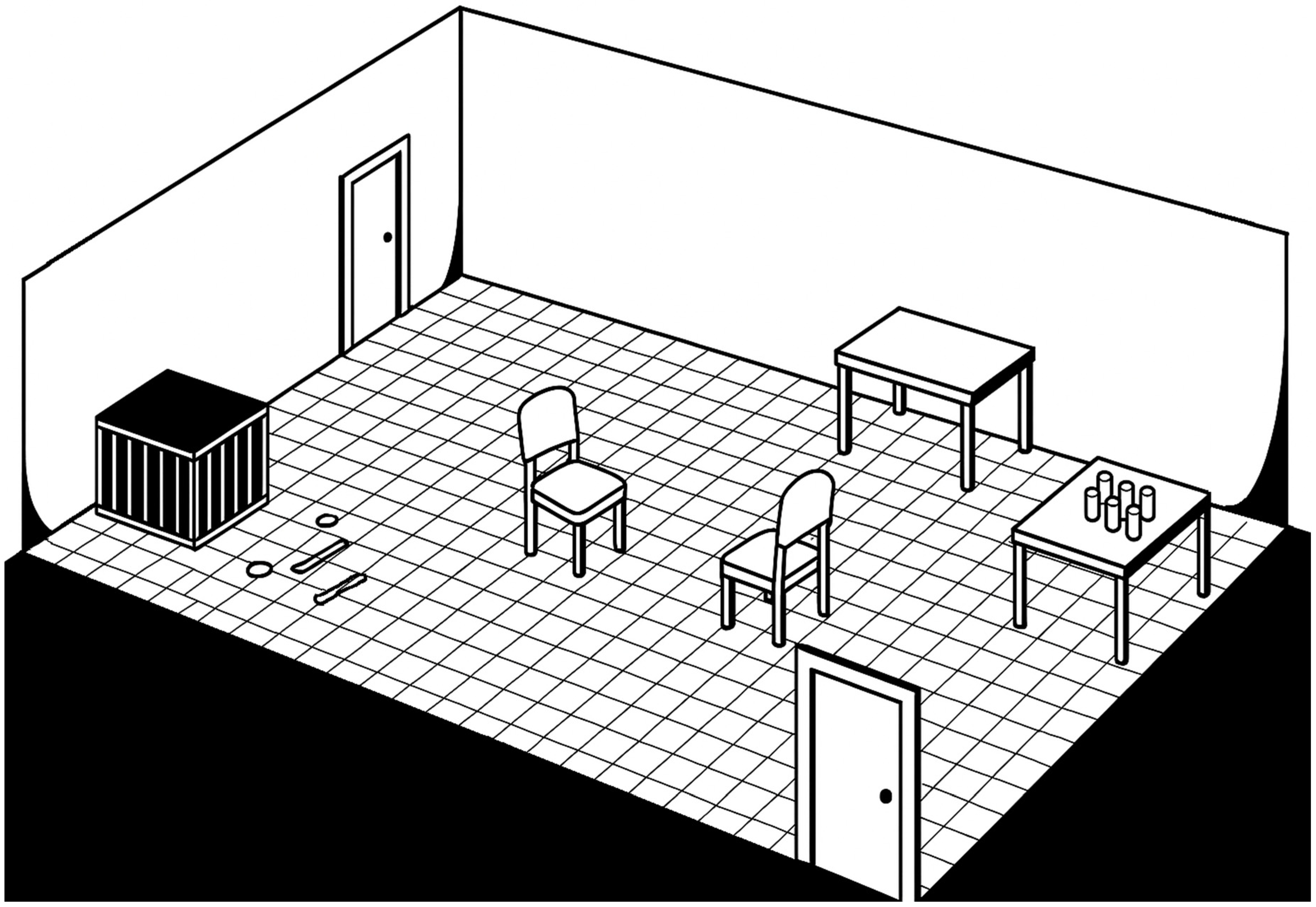

2.3.1. Experimental Setup

2.3.2. Experimental Procedure

Warm-Up Phase (1 min)

Testing Phase (12 min)

- Sit on the chair: the owner/stranger did not initiate interaction with the dog, but responded if the dog initiated the interaction (e.g., by placing its head on the owner’s knee) when it was allowed for the person to briefly pet the dog (i.e., a few hand-strokes to the head).

- Cube carrying: the owner/stranger carried the wooden building blocks from one table to another, completely ignoring the dog.

- Playing with the dog: The owner/stranger played with the dog using the available toys in the room in a natural manner. If the dog did not want to play, the owner/stranger petted the dog instead.

- Leave the room: the owner/stranger left the room without saying anything to the dog.

- Enter the room: After entering the room, the owner/stranger paused beside the door for 5 s. If the dog approached immediately, they greeted and petted the dog. If the dog did not approach, they verbally greeted the dog, waited for 5 s, then took a seat.

2.4. Behavioural Coding

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Attachment Dimension

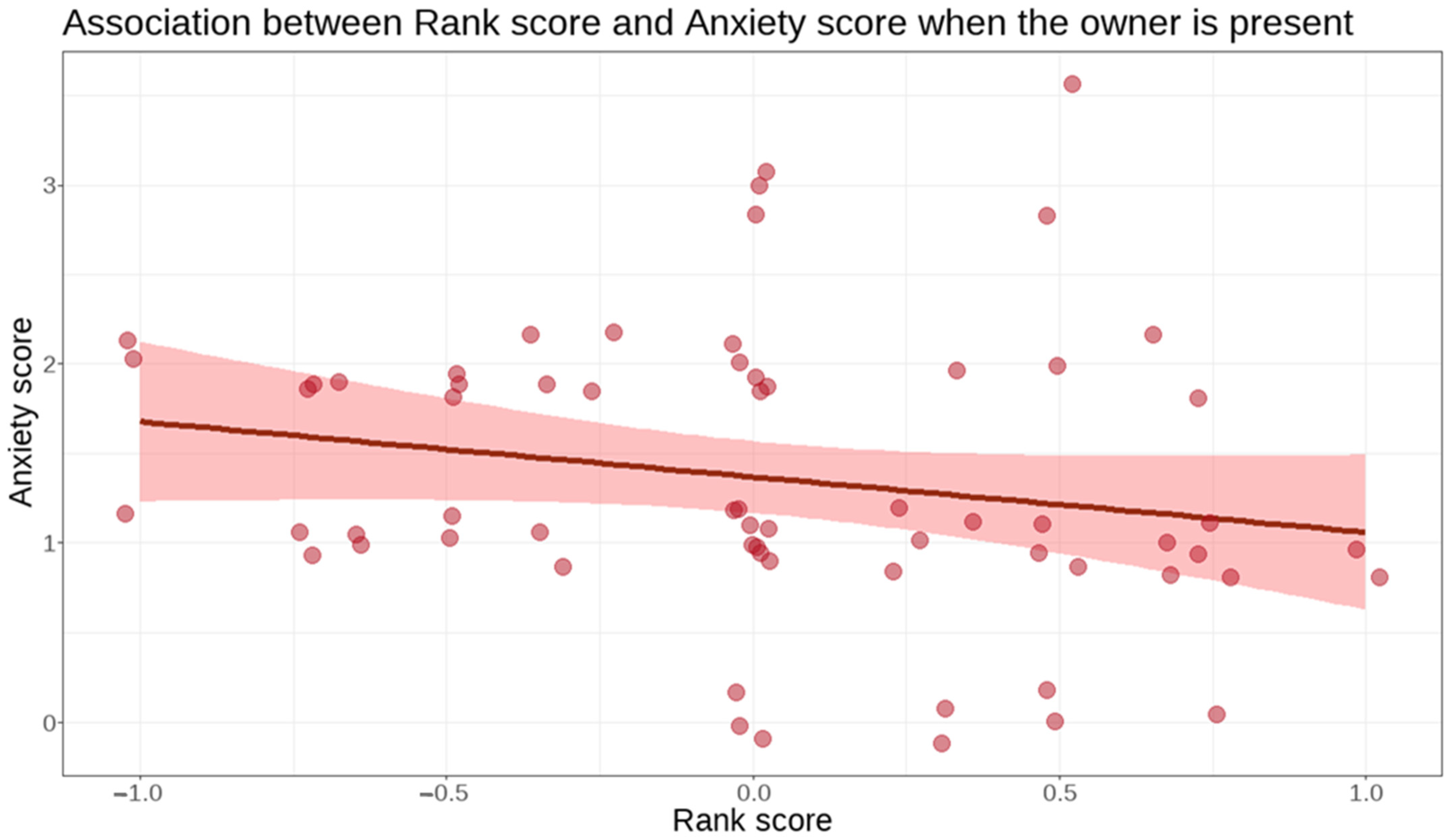

3.2. Anxiety Dimension

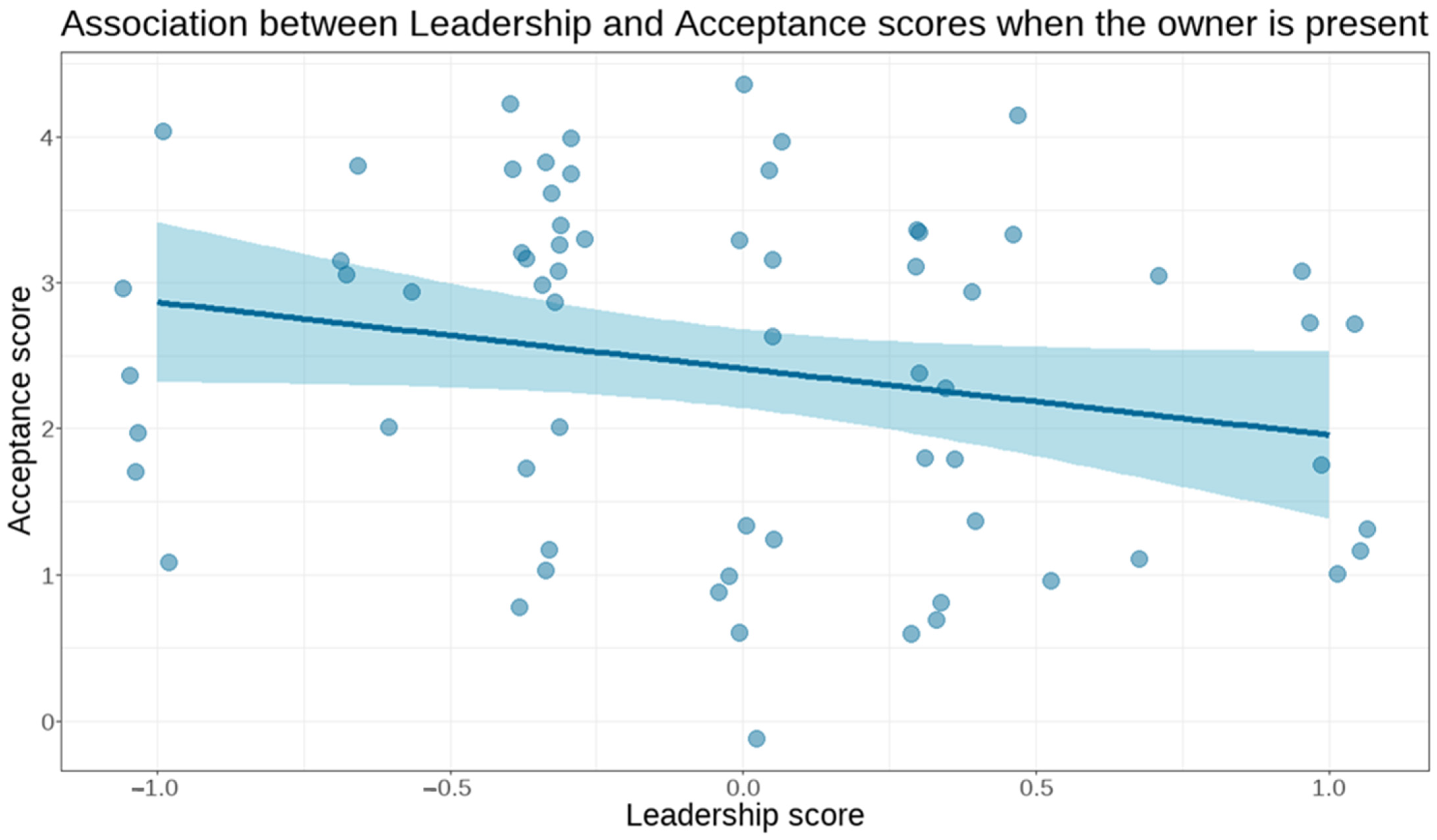

3.3. Acceptance Dimension

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Larson, G.; Karlsson, E.K.; Perri, A.; Webster, M.T.; Ho, S.Y.; Peters, J.; Lindblad-Toh, K. Rethinking dog domestication by integrating genetics, archeology, and biogeography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 8878–8883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentosela, M.; Wynne, C.D.L.; D’orazio, M.; Elgier, A.; Udell, M.A. Sociability and gazing toward humans in dogs and wolves: Simple behaviors with broad implications. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 2016, 105, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topál, J.; Miklósi, Á.; Gácsi, M.; Dóka, A.; Pongrácz, P.; Kubinyi, E.; Csányi, V. The dog as a model for understanding human social behavior. Adv. Study Behav. 2009, 39, 71–116. [Google Scholar]

- Pongrácz, P.; Dobos, P. What is a companion animal? An ethological approach based on Tinbergen’s four questions. Critical review. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2023, 267, 106055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppinger, R.; Coppinger, L. What Is a Dog? University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee, D.; Sau, S.; Bhadra, A. Free-ranging dogs understand human intentions and adjust their behavioral responses accordingly. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 6, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boitani, L.; Ciucci, P.; Ortolani, A. Behaviour and social ecology of free-ranging dogs. In The Behavioural Biology of Dogs; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2007; pp. 147–165. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall-Pescini, S.; Cafazzo, S.; Virányi, Z.; Range, F. Integrating social ecology in explanations of wolf–dog behavioral differences. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2017, 16, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miklósi, Á.; Topál, J. What does it take to become ‘best friends’? Evolutionary changes in canine social competence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2013, 17, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Range, F.; Marshall-Pescini, S. Comparing wolves and dogs: Current status and implications for human ‘self-domestication’. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2022, 26, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Range, F.; Marshall-Pescini, S. The socio-ecology of free-ranging dogs. In Wolves and Dogs: Between Myth and Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 83–110. [Google Scholar]

- Kogan, L.R.; Wallace, J.E.; Hellyer, P.W.; Carr, E.C. Canine caregivers: Paradoxical challenges and rewards. Animals 2022, 12, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Range, F.; Virányi, Z. Tracking the evolutionary origins of dog-human cooperation: The “Canine Cooperation Hypothesis”. Front. Psychol. 2015, 5, 110912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminski, J.; Nitzschner, M. Do dogs get the point? A review of dog–human communication ability. Learn. Motiv. 2013, 44, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siniscalchi, M.; d’Ingeo, S.; Minunno, M.; Quaranta, A. Communication in dogs. Animals 2018, 8, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, J.W.W.; Resende, B.; Savalli, C. A review of the unsolvable task in dog communication and cognition: Comparing different methodologies. Anim. Cogn. 2021, 24, 907–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, L.; Salobir, K.; Mundry, R.; Cimarelli, G. Selective overimitation in dogs. Learn. Behav. 2020, 48, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topál, J.; Kis, A.; Oláh, K. Dogs’ sensitivity to human ostensive cues: A unique adaptation? In The Social Dog; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 319–346. [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque, N.; Mills, D.S.; Guo, K.; Wilkinson, A.; Resende, B. Dogs can infer implicit information from human emotional expressions. Anim. Cogn. 2022, 25, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gácsi, M.; Kara, E.; Belényi, B.; Topál, J.; Miklósi, Á. The effect of development and individual differences in pointing comprehension of dogs. Anim. Cogn. 2009, 12, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brubaker, L.; Dasgupta, S.; Bhattacharjee, D.; Bhadra, A.; Udell, M.A. Differences in problem-solving between canid populations: Do domestication and lifetime experience affect persistence? Anim. Cogn. 2017, 20, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gácsi, M.; McGreevy, P.; Kara, E.; Miklósi, Á. Effects of selection for cooperation and attention in dogs. Behav. Brain Funct. 2009, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobos, P.; Pongrácz, P. Would you detour with me? Association between functional breed selection and social learning in dogs sheds light on elements of dog–human cooperation. Animals 2023, 13, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariti, C.; Ricci, E.; Zilocchi, M.; Gazzano, A. Owners as a secure base for their dogs. Behaviour 2013, 150, 1275–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gácsi, M.; Topál, J.; Miklósi, Á.; Dóka, A.; Csányi, V. Attachment behavior of adult dogs (Canis familiaris) living at rescue centers: Forming new bonds. J. Comp. Psychol. 2001, 115, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, R.; Perry, R.; Sloan, A.; Kleinhaus, K.; Burtchen, N. Infant bonding and attachment to the caregiver: Insights from basic and clinical science. Clin. Perinatol. 2011, 38, 643–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Rosmalen, L.; Van der Veer, R.; Van der Horst, F. Ainsworth’s strange situation procedure: The origin of an instrument. J. Hist. Behav. Sci. 2015, 51, 261–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topál, J.; Miklósi, Á.; Csányi, V.; Dóka, A. Attachment behavior in dogs (Canis familiaris): A new application of Ainsworth’s (1969) Strange Situation Test. J. Comp. Psychol. 1998, 112, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, K.N.; Ellison, W.D.; Scott, L.N.; Bernecker, S.L. Attachment style. J. Clin. Psychol. 2011, 67, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggio, G.; Gazzano, A.; Zsilák, B.; Carlone, B.; Mariti, C. Quantitative behavioral analysis and qualitative classification of attachment styles in domestic dogs: Are dogs with a secure and an insecure-avoidant attachment different? Animals 2020, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenkei, R.; Carreiro, C.; Gácsi, M.; Pongrácz, P. The relationship between functional breed selection and attachment pattern in family dogs (Canis familiaris). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 235, 105231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, R.; Protopopova, A.; Bhadra, A. The human-animal bond and at-home behaviours of adopted Indian free-ranging dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2023, 268, 106014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanni, R.; Cafazzo, S.; Abis, A.; Barillari, E.; Valsecchi, P.; Natoli, E. Age-graded dominance hierarchies and social tolerance in packs of free-ranging dogs. Behav. Ecol. 2017, 28, 1004–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trisko, R.K.; Sandel, A.A.; Smuts, B. Affiliation, dominance and friendship among companion dogs. Behaviour 2016, 153, 693–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vékony, K.; Pongrácz, P. Many faces of dominance: The manifestation of cohabiting companion dogs’ rank in competitive and non-competitive scenarios. Anim. Cogn. 2024, 27, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ákos, Z.; Beck, R.; Nagy, M.; Vicsek, T.; Kubinyi, E. Leadership and path characteristics during walks are linked to dominance order and individual traits in dogs. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014, 10, e1003446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pongrácz, P.; Vida, V.; Bánhegyi, P.; Miklósi, Á. How does dominance rank status affect individual and social learning performance in the dog (Canis familiaris)? Anim. Cogn. 2008, 11, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vékony, K.; Prónik, F.; Pongrácz, P. Personalized dominance–a questionnaire-based analysis of the associations among personality traits and social rank of companion dogs. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2022, 247, 105544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, M.D. Attachment and expolatory behavior of one-year-olds in strange situation. In Determinants of Infant Behavior; Methuen: London, UK, 1969; pp. 111–136. [Google Scholar]

- Faragó, T.; Pongrácz, P.; Range, F.; Virányi, Z.; Miklósi, Á. ‘The bone is mine’: Affective and referential aspects of dog growls. Anim. Behav. 2010, 79, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovács, K.; Virányi, Z.; Kis, A.; Turcsán, B.; Hudecz, Á.; Marmota, M.T.; Topál, J. Dog-owner attachment is associated with oxytocin receptor gene polymorphisms in both parties. A comparative study on Austrian and Hungarian border collies. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topál, J.; Miklósi, Á.; Csányi, V. Dog-human relationship affects problem solving behavior in the dog. Anthrozoös 1997, 10, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, D.; Bhadra, A. Humans dominate the social interaction networks of urban free-ranging dogs in India. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vékony, K.; Bakos, V.; Pongrácz, P. Rank-Related Differences in Dogs’ Behaviours in Frustrating Situations. Animals 2024, 14, 3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongrácz, P.; Dobos, P.; Prónik, F.; Vékony, K. Done deal—Cohabiting dominant and subordinate dogs differently rely on familiar demonstrators in a detour task. BMC Biol. 2025, 23, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuerbacher, E.N.; Wynne, C.D. Dogs don’t always prefer their owners and can quickly form strong preferences for certain strangers over others. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 2017, 108, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pongrácz, P.; Gómez, S.A.; Lenkei, R. Separation-related behaviour indicates the effect of functional breed selection in dogs (Canis familiaris). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2020, 222, 104884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, S.; Bleuer-Elsner, S.; Muller, G.; Médam, T.; Chevallier, J.; Gaultier, E. Attachment Axis Disorders. In Veterinary Psychiatry of the Dog: Diagnosis and Treatment of Behavioral Disorders; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 407–451. [Google Scholar]

- Konok, V.; Marx, A.; Faragó, T. Attachment styles in dogs and their relationship with separation-related disorder—A questionnaire based clustering. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2019, 213, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Question | This Dog | One of My Other Dogs | Neither/Depends on the Situation | I Do Not Know/Not Applicable | Rank Subscore Categories |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| When a stranger comes to the house, which dog starts to bark first (or if they start to bark together, which dog barks more or longer)? | 1 | −1 | 0 | N/A | leadership |

| Which dog licks more often the other dog’s mouth? | −1 | 1 | 0 | N/A | formal |

| If the dogs receive food at the same time and at the same spot, which dog starts to eat first or eats the other dog’s food? | 1 | −1 | 0 | N/A | agonistic |

| If the dogs start to fight, which dog usually wins? | 1 | −1 | 0 | N/A | agonistic |

| If they receive a special reward (e.g., a marrow bone), which dog obtains it? | 1 | −1 | 0 | N/A | agonistic |

| Which dog goes in the front during walks? | 1 | −1 | 0 | N/A | leadership |

| Which dog acquires the better resting place? | 1 | −1 | 0 | N/A | agonistic |

| If your dogs are being attacked, which dog faces the threat in the front? | 1 | −1 | 0 | N/A | leadership |

| Ep | Time | Owner | Stranger |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 0:00–0:30 | sits still on the chair | absent |

| 0:30–1:00 | carries cubes, from one table to the other, one at a time | ||

| 1:00–1:30 | sits still on the chair | ||

| 1:30–2:00 | plays with the dog | ||

| 2:00 | when the door opens sits still on the chair | enters the room, greets briefly if the dog approaches (5–10 s) | |

| 2. | 2′–2:30 | sits still on the chair | sits still on the chair |

| 2:30–3:00 | carries cubes, from one table to the other, one at a time | ||

| 3:00–3:30 | sits still on the chair | ||

| 3:30–4:00 | plays with the dog | ||

| 4:00 | leaves the leash on the chair and exits the room | when the door closes after the owner leaves, sits still on the chair | |

| 3. | 4′–4:30 | absent | sits still on the chair |

| 4:30–5:00 | carries cubes, from one table to the other, one at a time | ||

| 5:00–5:30 | sits still on the chair | ||

| 5:30–6:00 | plays with the dog | ||

| 6:00 | enters the room, starts playing with the dog; stops playing when the stranger leaves | after the owner initiates play, leaves the room | |

| 4. | 6′–6:30 | sits still on the chair | absent |

| 6:30–7:00 | carries cubes, from one table to the other, one at a time | ||

| 7:00–7:30 | sits still on the chair | ||

| 7:30–8:00 | plays with the dog | ||

| 8:00 | leaves the room | ||

| 5. | 8′–9:00 | dog alone, owner absent | absent |

| 9:00–9′ | enters the room, greets briefly if the dog approaches | ||

| 9′–10:00 | absent | sits still on the chair | |

| 10:00 | leaves the room | ||

| 6. | 10′–11:00 | dog alone, owner absent | absent |

| 11:00 | enters the room | ||

| 11′–12:00 | sits still on the chair | ||

| 12:00 | sits 10 s after the door opens, then puts the leash on the dog and leaves the room with the experimenter |

| Dimension | Context | Episode | Description of Behaviour | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATTACHMENT | SST score | |||

| Owner (O) PRESENT | Proximity | 1, 2, 4, 6 | D is close to O (closest body part is within 1 m)—in most of the time when D does not explore or play | 1 |

| BlockO-1 | 1 | during the first block-carrying D watches OR follows O for more than half of the time | 1 | |

| LeaveO-1 | 2e | when O first leaves, D follows O to the door (at least within 1 m from door) | 1 | |

| EnterO-1 | 4s | when O first enters, D approaches O at once (in reaching distance) AND D wags tail | 1 | |

| BlockO-2 | 4 | during the second block-carrying C/D watches OR follows O for more than half of the time | 1 | |

| LeaveO-2 | 4e | when O leaves the second time, D follows O to the door (at least within 1 m from door) | 0.5 | |

| EnterO-2 | 6 | when O enters the second time, D approaches O at once (in reaching distance) AND D wags tail/jumps/spins | 0.5 | |

| Owner ABSENT | DoorS-1 | 3 | D stands by OR orients at O’s door (for at least 5 s—score 0.5; almost all the time—score 1) during first separation | 1 |

| NoPlayS | 3 | D does not play with S, although it played with her more than 10 s in Episode 2 (in O’s presence) | 1 | |

| VocalS | 3, 5 | D vocalises (any occurrence, except D asking for ball from S) | 0.5 | |

| Chair | 3, 5 | D is for more than half of the time at the chair of O if it is not at the door | 0.5 | |

| DoorS-2 | 5 | D stands by OR orients at O’s door (for at least 5 s) during second separation | 1 | |

| EscapeS | 5 | when S enters, D first tries to sneak out through the door instead of greeting S | 0.5 | |

| Door-3 | 6 | D stands by OR orients at O’s door (for at least 5 s) during third separation | 0.5 | |

| sum | 11.0 | |||

| ANXIETY | ||||

| Owner PRESENT | DoorO-1 | 1 | D stands at any door (for at least 5 s—score 1, almost all the time during sit/play—score 2) | 2 |

| ContactO | 1, 2 | D seeks contact with O before the first separation from O | 1 | |

| VocalO | 1, 2, 4, 6 | D vocalises (except D asking for the ball or greeting the O) | 1 | |

| Passive | 1, 2, 4 | D does not play and does not explore for more than a few seconds (except in a pretty relaxed position) | 1 | |

| Hide | 1, 2, 4, 6 | D stays (hides) under/behind O’s chair for more than half of the time of the sit phases | 1 | |

| Lead | 1, 2e, 4, 4e | as soon as O stands up, D approaches the door (going ahead of O) (4 × 0.5) | 2 | |

| DoorO-2 | 4 | D stands at any door for at least 5 s | 1 | |

| DoorO-3 | 6 | D stands at any door for at least 5 s | 1 | |

| Owner ABSENT | SeparationS | 3 | at separation, D vocalises OR scratches the door, or D runs around up and down for at least 10 s | 1 |

| Calm1 | 3 | D plays or lies down comfortably (head down) for more than 10 s | 1 | |

| FollowS | 4 | D follows S to the door when she leaves | 1 | |

| Separation | 5, 6 | at separation, D vocalises OR scratches the door, or D runs around up and down for at least 10 s (2 × 0.5) | 1 | |

| Calm2 | 5, 6 | D plays or lies down comfortably (head down) for more than 10 s when alone (in sum) | 1 | |

| sum | 11.0 | |||

| ACCEPTANCE | ||||

| Owner PRESENT | EnterS | 1e | D approaches S when she first enters (at once, within reaching distance) | 1 |

| GreetS | 1e | when S first enters, D establishes physical contact with her AND D wags tail | 1 | |

| BlockS-1 | 2 | during the block-carrying part, D watches or follows S for more than half of the time | 1 | |

| PlayS | 2 | D plays with S at least for 10 s | 1 | |

| Anytime | RubS/ToyS | 2, 3, 5 | D offers a toy to S (not during play) | 1 |

| ContactS | 2, 3, 5 | D seeks physical contact with S (jumps on, snuggles up to, or nudges) during the episodes | 1 | |

| AvoidS | 2, 3 | D avoids S during play (stands off, avoids her touch) | 1 | |

| Owner ABSENT | PoximityS | 3, 5 | D stays close (closest body part is within 1 m) to S in sit phases (at least for 5 s—1, almost all the time—2) | 2 |

| BlockS-2 | 3 | during the block-carrying part, D watches or follows S for more than half of the time | 1 | |

| PlayS-2 | 3 | D plays with S also during separation (a little—1, a lot—2) | 2 | |

| GreetS-2 | 5 | when S enters second time, D approaches her (0.5) AND establishes physical contact with her while D wags the tail (1) | 1 | |

| sum | 11.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bakos, V.; Vékony, K.; Pongrácz, P. Hierarchy-Dependent Behaviour of Dogs in the Strange Situation Test: High-Ranking Dogs Show Less Stress and Behave Less Friendly with a Stranger in the Presence of Their Owner. Animals 2025, 15, 1916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15131916

Bakos V, Vékony K, Pongrácz P. Hierarchy-Dependent Behaviour of Dogs in the Strange Situation Test: High-Ranking Dogs Show Less Stress and Behave Less Friendly with a Stranger in the Presence of Their Owner. Animals. 2025; 15(13):1916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15131916

Chicago/Turabian StyleBakos, Viktória, Kata Vékony, and Péter Pongrácz. 2025. "Hierarchy-Dependent Behaviour of Dogs in the Strange Situation Test: High-Ranking Dogs Show Less Stress and Behave Less Friendly with a Stranger in the Presence of Their Owner" Animals 15, no. 13: 1916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15131916

APA StyleBakos, V., Vékony, K., & Pongrácz, P. (2025). Hierarchy-Dependent Behaviour of Dogs in the Strange Situation Test: High-Ranking Dogs Show Less Stress and Behave Less Friendly with a Stranger in the Presence of Their Owner. Animals, 15(13), 1916. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15131916