The Impact of Psychosocial Factors on the Human—Pet Bond: Insights from Cat and Dog Owners

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedure

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Statistical Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Information

3.2. Attachment to Pets

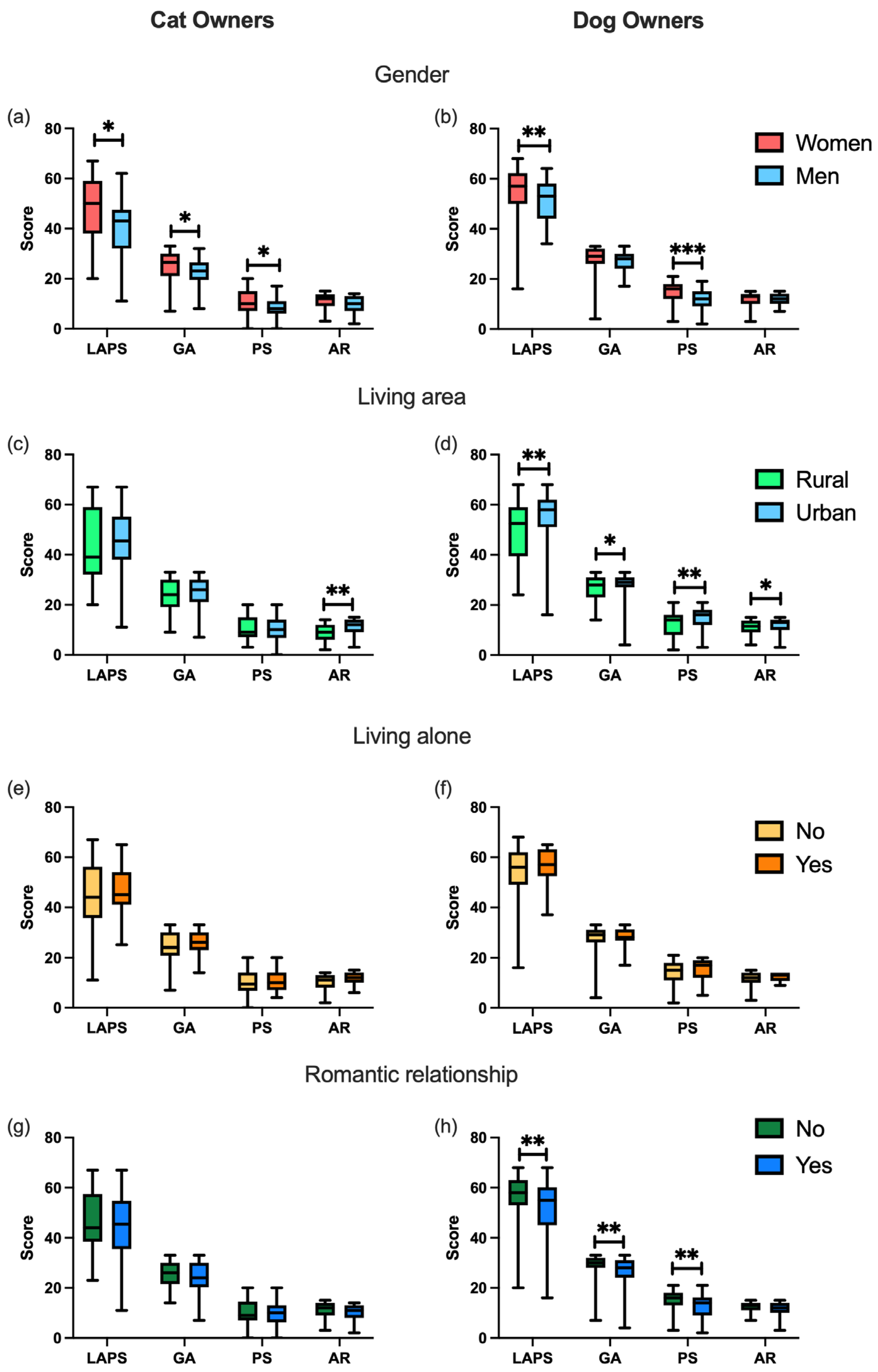

3.3. Psychosocial Factors and Pet Attachment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AR | Animal Rights |

| GA | General Attachment |

| LAPS | Lexington Pet Attachment Scale |

| MOS-SSS | Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey |

| PS | Person Substitution |

| UCLA | University of California, Los Angeles |

| WEMWBS | Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale |

References

- REIAC. Red Española de Identificación de Animales de Compañia. Available online: https://www.reiac.es/reiac-info-02.php?lang=ESP (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- López-Cepero, J.; Martos-Montes, R.; Ordóñez, D. Classification of Animals as Pet, Pest, or Profit: Consistency and Associated Variables Among Spanish University Students. Anthrozoös 2021, 34, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petcare, M. A Better World for Pets: Radiografía de las mascotas en España. Petshops Mag. 2024. Available online: https://petshopsmagazine.com/articulos/perros/estudio-de-mars-a-better-world-for-pets-radiografia-de-las-mascotas-en-espana/ (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Driscoll, C.A.; Macdonald, D.W.; O’Brien, S.J. From wild animals to domestic pets, an evolutionary view of domestication. (in eng). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106 (Suppl. 1), 9971–9978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, L.E. All in the Family: Pets and Family Structure. Populations 2025, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbreich, E.D.; Hefner, T.D.; Healy, A.S.; Van Allen, J. Measurement of attachment in human-animal interaction research. Hum.-Anim. Interact. 2024, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RDepue, A.; Morrone-Strupinsky, J.V. A neurobehavioral model of affiliative bonding: Implications for conceptualizing a human trait of affiliation. Behav. Brain Sci. 2005, 28, 313–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, O. Biophilia; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1984; p. 157. [Google Scholar]

- Serpell, J. In the Company of Animals: A Study of Human-Animal Relationships; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996; p. 283. [Google Scholar]

- Sable, P. The Pet Connection: An Attachment Perspective. Clin. Soc. Work. J. 2013, 41, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretherton, I. Attachment Theory: Retrospect and Prospect. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child. Dev. 1985, 50, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melfi, V.; Skyner, L.; Birke, L.; Ward, S.J.; Shaw, W.S.; Hosey, G. Furred and feathered friends: How attached are zookeepers to the animals in their care? Zoo. Biol. 2022, 41, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandøe, P.; Palmer, C.; Corr, S.A.; Springer, S.; Lund, T.B. Do people really care less about their cats than about their dogs? A comparative study in three European countries. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1237547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hielscher, B.; Gansloßer, U.; Froboese, I. Attachment to Dogs and Cats in Germany: Translation of the Lexington Attachment to Pets Scale (LAPS) and Description of the Pet Owning Population in Germany. Hum.-Anim. Interact. Bull. 2019, 7, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.P.; Garrity, T.F.; Stallones, L. Psychometric Evaluation of the Lexington Attachment to Pets Scale (Laps). Anthrozoös 1992, 5, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, M.K. The Relationship between Types of Human–Animal Interaction and Attitudes about Animals: An Exploratory Study. Anthrozoös 2014, 27, 295–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egaña-Marcos, E.; Goñi-Balentziaga, O.; Azkona, G. A Study on the Attachment to Pets Among Owners of Cats and Dogs Using the Lexington Attachment to Pets Scale (LAPS) in the Basque Country. Animals 2025, 15, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albuquerque, N.; Corte, S.; Feld, A.; Otta, E.; Prist, R.; Johnson, T.P. LAPS SA: Measuring Attachment to Dogs and Cats Among South American Countries. Psychol. Rep. 2025, 332941251315072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpell, J.; Dog, T.D. Behaviour and Interactions with People (The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behaviour, and Interactions with People); Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, J. Why do people love their pets? Evol. Hum. Behav. 1997, 18, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stammbach, K.B.; Turner, D.C. Understanding the Human—Cat Relationship: Human Social Support or Attachment. Anthrozoos 1999, 12, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, T.; Zaboski-Pena, L.; Harroche, I.; Théodon, O.; Meynadier, A. Investigating influences on pet attachment in France: Insights from the adaptation of the French Lexington Attachment to Pets Scale. Hum.-Anim. Interact. 2024, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugent, W.R.; Daugherty, L. A Measurement Equivalence Study of the Family Bondedness Scale: Measurement Equivalence Between Cat and Dog Owners. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 812922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poresky, R.H.; Daniels, A.M. Demographics of Pet Presence and Attachment. Anthrozoös 1998, 11, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranyiová, E.; Holub, A.; Tyrlík, M.; Janáčková, B.; Ernstová, M. The Influence of Urbanization on the Behaviour of Dogs in the Czech Republic. Acta Vet. Brno 2005, 74, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corr, S.A.; Lund, T.B.; Sandøe, P.; Springer, S. Cat and dog owners’ expectations and attitudes towards advanced veterinary care (AVC) in the UK, Austria and Denmark. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0299315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, D.L.; Treacy, K.R. Pet attachment and owner personality. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1406590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Albuquerque, N.S.; Costa, D.B.; Rodrigues, G.D.R.; Sessegolo, N.S.; Moret-Tatay, C.; Irigaray, T.Q. Adaptation and psychometric properties of Lexington Attachment to Pets Scale: Brazilian version (LAPS-B). J. Vet. Behav. 2023, 61, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J.; Boden, T.; Mocho, J.P.; Johnson, T. Refining the unilateral ureteral obstruction mouse model: No sham, no shame. Lab. Anim. 2021, 55, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Testoni, I.; De Vincenzo, C.; Campigli, M.; Manzatti, A.C.; Ronconi, L.; Uccheddu, S. Validation of the HHHHHMM Scale in the Italian Context: Assessing Pets’ Quality of Life and Qualitatively Exploring Owners’ Grief. Animals 2023, 13, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; De Cataldo, L.; Ronconi, L.; Zamperini, A. Pet Loss and Representations of Death, Attachment, Depression, and Euthanasia. Anthrozoös 2017, 30, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagley, D.K.; Gonsman, V.L. Pet attachment and personality type. Anthrozoös 2005, 18, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reevy, G.M.; Delgado, M.M. Are emotionally attached companion animal caregivers conscientious and neurotic? Factors that affect the human-companion animal relationship. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2015, 18, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egaña-Marcos, E.; Collantes, E.; Diez-Solinska, A.; Azkona, G. The Influence of Loneliness, Social Support and Income on Mental Well-Being. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2025, 15, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Mann, F.; Lloyd-Evans, B.; Ma, R.; Johnson, S. Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, F.; Wang, J.; Pearce, E.; Ma, R.; Schlief, M.; Lloyd-Evans, B.; Ikhtabi, S.; Johnson, S. Loneliness and the onset of new mental health problems in the general population. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 2161–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zasloff, R.L.; Kidd, A.H. Loneliness and pet ownership among single women. Psychol. Rep. 1994, 75, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, A.R.; Brown, C.M.; Shoda, T.M.; Stayton, L.E.; Martin, C.E. Friends with benefits: On the positive consequences of pet ownership. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2011, 101, 1239–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meehan, M.; Massavelli, B.; Pachana, N. Using attachment theory and social support theory to examine and measure pets as sources of social support and attachment figures. Anthrozoös 2017, 30, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, A.R.; Lloyd, E.P.; Humphrey, B.T. We are family: Viewing pets as family members improves wellbeing. Anthrozoös 2019, 32, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretzler, B.; König, H.H.; Hajek, A. Pet ownership, loneliness, and social isolation: A systematic review. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2022, 57, 1935–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiloh, S.; Sorek, G.; Terkel, J. Reduction of State-Anxiety by Petting Animals in a Controlled Laboratory Experiment. Anxiety Stress. Coping 2003, 16, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, A.; Klug, S.J.; Abraham, A.; Westenberg, E.; Schmidt, V.; Winkler, A.S. Animal-Assisted Interventions Improve Mental, But Not Cognitive or Physiological Health Outcomes of Higher Education Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2022, 22, 1597–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charry-Sánchez, J.D.; Pradilla, I.; Talero-Gutiérrez, C. Animal-assisted therapy in adults: A systematic review. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2018, 32, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peel, N.; Nguyen, K.; Tannous, C. The Impact of Campus-Based Therapy Dogs on the Mood and Affect of University Students. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grajfoner, D.; Harte, E.; Potter, L.M.; McGuigan, N. The Effect of Dog-Assisted Intervention on Student Well-Being, Mood, and Anxiety. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017, 14, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chute, A.; Vihos, J.; Johnston, S.; Buro, K.; Velupillai, N. The effect of animal-assisted intervention on undergraduate students’ perception of momentary stress. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1253104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, J.; Chur-Hansen, A.; Winefield, H. Mental health implications of human attachment to companion animals. J. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 68, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonacopoulos, N.M.D.; Pychyl, T.A. An examination of the potential role of pet ownership, human social support and pet attachment in the psychological health of individuals living alone. Anthrozoös 2010, 23, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northrope, K.; Shnookal, J.; Ruby, M.B.; Howell, T.J. The Relationship Between Attachment to Pets and Mental Health and Wellbeing: A Systematic Review. Animals 2025, 15, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macía, P.; Goñi-Balentziaga, O.; Vegas, O.; Azkona, G. Professional quality of life among Spanish veterinarians. Vet. Rec. Open 2022, 9, e250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velarde-Mayol, C.; Fragua-Gil, S.; García-de-Cecilia, J.M. Validación de la escala de soledad de UCLA y perfil social en la población anciana que vive sola. Semer.-Med. Fam. 2016, 42, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Martín, E.; Ardura, D. El tamaño del efecto en la publicación científica. Educ. XX1 2023, 26, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shore, E.R.; Douglas, D.K.; Riley, M.L. What’s in it for the companion animal? Pet attachment and college students’ behaviors toward pets. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2005, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Fuentes, J.M.; Hombrados-Mendieta, M.I.; García-Leiva, P. Social support and life satisfaction among gay men in Spain. J. Homosex. 2012, 59, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, J.; Casado, T.; Sá-Couto, P.; Guerra, S.; Sousa, L. Spanish Older LGBT+ Adults: Satisfaction with Life and Generativity. Sex. Res. Soc. Policy 2024, 21, 1270–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matías, R.; Matud, M.P. Sexual Orientation, Health, and Well-Being in Spanish People. Healthcare 2024, 12, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macía, P.; Gorbeña, S.; Barranco, M.; Iglesias, N.; Iraurgi, I. A global health model integrating psychological variables involved in cancer through a longitudinal study. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 873849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SoledadES. Loneliness in Spain Barometer. Available online: https://www.soledades.es/estudios/barometro-soledad-no-deseada-espana-2024 (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Castellví, P.; Forero, C.G.; Codony, M.; Vilagut, G.; Brugulat, P.; Medina, A.; Gabilondo, A.; Mompart, A.; Colom, J.; Tresserras, R.; et al. The Spanish version of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS) is valid for use in the general population. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goñi-Balentziaga, O.; Azkona, G. Perceived professional quality of life and mental well-being among animal facility personnel in Spain. Lab. Anim. 2023, 58, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soldevila-Domenech, N.; Forero, C.G.; Alayo, I.; Capella, J.; Colom, J.; Malmusi, D.; Mompart, A.; Mortier, P.; Puértolas, B.; Sánchez, N.; et al. Mental well-being of the general population: Direct and indirect effects of socioeconomic, relational and health factors. Qual. Life Res. 2021, 30, 2171–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, T.C.; Chandra, R.; Friend, D.M.; Finkel, E.; Dayrit, G.; Miranda, J.; Brooks, J.M.; Iñiguez, S.D.; O’dOnnell, P.; Kravitz, A.; et al. Nucleus accumbens medium spiny neuron subtypes mediate depression-related outcomes to social defeat stress. Biol. Psychiatry 2015, 77, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, H.L.; Rushton, K.; Lovell, K.; Bee, P.; Walker, L.; Grant, L.; Rogers, A. The power of support from companion animals for people living with mental health problems: A systematic review and narrative synthesis of the evidence. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbey, A.; McNicholas, J.; Collis, G.M. A longitudinal test of the belief that companion animal ownership can help reduce loneliness. Anthrozoös 2007, 20, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, S.; Mai, D.L.; Howell, T.J. Social support and wellbeing in cat and dog owners, and the moderating influence of pet–owner relationship quality. Anthrozoös 2023, 36, 891–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ramírez, M.T.; Landero-Hernández, R. Pet-Human Relationships: Dogs versus Cats. Animals 2021, 11, 2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, C.F.; Silva, L.; Soares, J.; Pinto, G.S.; Abrantes, C.; Cardoso, L.; Pires, M.A.; Sousa, H.; Mota, M.P. Walk or be walked by the dog? The attachment role. BMC Public. Health 2024, 24, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight, S.; Edwards, V. In the company of wolves: The physical, social, and psychological benefits of dog ownership. J. Aging Health 2008, 20, 437–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrelli, C.; Riggio, G.; Howell, T.J.; Piotti, P.; Diverio, S.; Albertini, M.; Mongillo, P.; Marinelli, L.; Baragli, P.; Di Iacovo, F.P.; et al. The Cat-Owner Relationship: Validation of the Italian C/DORS for Cat Owners and Correlation with the LAPS. Animals 2022, 13, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, T.J.; Bowen, J.; Fatjó, J.; Calvo, P.; Holloway, A.; Bennett, P.C. Development of the cat-owner relationship scale (CORS). Behav. Process. 2017, 141 Pt 3, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colleen, P.K. Dogs have masters, cats have staff: Consumers’ psychological ownership and their economic valuation of pets. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 99, 306–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liao, W.; Qin, Y. The effect of pet attachment on social support among young adult cat owners: The chain mediating roles of emotion regulation and empathy. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause-Parello, C.A.; Gulick, E.E. Situational factors related to loneliness and loss over time among older pet owners. West. J. Nurs. Res. 2013, 35, 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bures, R.M.; Mueller, M.K.; Gee, N.R. Measuring Human-Animal Attachment in a Large U.S. Survey: Two Brief Measures for Children and Their Primary Caregivers. Front. Public. Health 2019, 7, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo-Claverol, M.; Manuel-Canals, M.; Lobato-Rincón, L.L.; Rodriguez-Criado, N.; Roman-Casenave, M.; Musull-Dulcet, E.; Rodrigo-Claverol, E.; Pifarré, J.; Miró-Bernaus, Y. Human–Animal Bond Generated in a Brief Animal-Assisted Therapy Intervention in Adolescents with Mental Health Disorders. Animals 2023, 13, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Applebaum, J.W.; MacLean, E.L.; McDonald, S.E. Love, fear, and the human-animal bond: On adversity and multispecies relationships. Compr. Psychoneuroendocrinol. 2021, 7, 100071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cat Owner | Dog Owner | |

|---|---|---|

| n (%) | ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | 75 (68.8%) | 150 (79.4%) |

| Male | 34 (31.2%) | 39 (20.6%) |

| Living area | ||

| Rural | 23 (21.1%) | 52 (27.5%) |

| Urban | 86 (78.9%) | 137 (72.5%) |

| Living alone | ||

| No | 86 (78.9%) | 167 (88.4%) |

| Yes | 23 (21.1%) | 22 (11.6%) |

| Romantic relationship | ||

| No | 49 (44.9%) | 83 (43.9%) |

| Yes | 60 (55.1%) | 105 (56.1%) |

| Social support | ||

| Low | 6 (5.5%) | 1 (0.5%) |

| Average | 9 (8.6%) | 17 (8.9%) |

| High | 94 (85.9%) | 171 (90.6%) |

| Loneliness | ||

| Low | 48 (44%) | 96 (50.7%) |

| Average | 51 (46.8%) | 88 (46.6%) |

| High | 10 (9.2%) | 5 (2.7%) |

| Mental well-being | ||

| Low | 8 (7.3%) | 8 (4.2%) |

| Average | 51 (46.8%) | 85 (44.9%) |

| High | 50 (45.9%) | 96 (50.9%) |

| Group | Mean | SD | Median | Range | U | p | rbb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAPS | Cat owner | 45.4 | 12.35 | 44 | 11–67 | 6153 | <0.001 *** | 0.403 |

| Dog owner | 53.8 | 10.49 | 56 | 16–68 | ||||

| GA | Cat owner | 24.7 | 5.94 | 25 | 7–33 | 6799 | <0.001 *** | 0.340 |

| Dog owner | 27.9 | 4.77 | 29 | 4–33 | ||||

| PS | Cat owner | 10.2 | 4.78 | 10 | 0–20 | 5759 | <0.001 *** | 0.441 |

| Dog owner | 14.1 | 4.70 | 15 | 2–21 | ||||

| AR | Cat owner | 10.6 | 3.23 | 11 | 2–15 | 8042 | 0.001 ** | 0.219 |

| Dog owner | 11.8 | 3.23 | 12 | 3–15 |

| Social Support | Loneliness | Mental Well-Being | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAPS | Cat owners | 0.087 | 0.096 | −0.087 |

| Dog owners | −0.151 * | 0.147 * | −0.173 * | |

| GA | Cat owners | 0.117 | 0.015 | −0.014 |

| Dog owners | −0.026 | 0.046 | −0.080 | |

| PS | Cat owners | −0.022 | 0.183 | −0.145 |

| Dog owners | −0.236 ** | 0.215 ** | −0.234 ** | |

| AR | Cat owners | 0.163 | 0.099 | −0.048 |

| Dog owners | −0.104 | 0.125 | −0.143 |

| Standardized β | 95% CI | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAPS | |||||

| Gender | −0.2919 | −0.638–0.0538 | −1.666 | 0.097 | |

| Age | −0.2593 | −0.415–−0.1034 | −3.282 | 0.001 ** | |

| Living area | −0.4184 | −0.726–−0.1113 | −2.688 | 0.008 ** | |

| Living alone | −0.1670 | −0.611–0.2766 | −0.743 | 0.459 | |

| Romantic relationship | −0.1273 | −0.439–0.1842 | −0.806 | 0.421 | |

| Social support | −0.1127 | −0.297–0.0712 | −1.209 | 0.228 | |

| Loneliness | −0.0596 | −0.255–0.1356 | −0.602 | 0.548 | |

| Mental well-being | −0.0933 | −0.275–0.0882 | −1.014 | 0.312 | |

| PS | |||||

| Gender | −0.4882 | −0.811–−0.1651 | −2.982 | 0.003 ** | |

| Age | −0.3154 | −0.461–−0.1697 | −4.271 | <0.001 *** | |

| Living area | −0.4290 | −0.716–−0.1419 | −2.949 | 0.004 ** | |

| Living alone | −0.1871 | −0.602–0.2275 | −0.890 | 0.374 | |

| Romantic relationship | −0.0574 | −0.349–0.2338 | −0.389 | 0.698 | |

| Social support | −0.1842 | −0.356–−0.0124 | −2.115 | 0.036 * | |

| Loneliness | −0.0195 | −0.202–0.1630 | −0.210 | 0.834 | |

| Mental well-being | −0.0934 | −0.263–0.0762 | −1.087 | 0.279 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Azkona, G. The Impact of Psychosocial Factors on the Human—Pet Bond: Insights from Cat and Dog Owners. Animals 2025, 15, 1895. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15131895

Azkona G. The Impact of Psychosocial Factors on the Human—Pet Bond: Insights from Cat and Dog Owners. Animals. 2025; 15(13):1895. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15131895

Chicago/Turabian StyleAzkona, Garikoitz. 2025. "The Impact of Psychosocial Factors on the Human—Pet Bond: Insights from Cat and Dog Owners" Animals 15, no. 13: 1895. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15131895

APA StyleAzkona, G. (2025). The Impact of Psychosocial Factors on the Human—Pet Bond: Insights from Cat and Dog Owners. Animals, 15(13), 1895. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15131895