Determinants of Pet-Friendly Tourism Behavior: An Empirical Analysis from Chile

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Intention to Travel with Pets

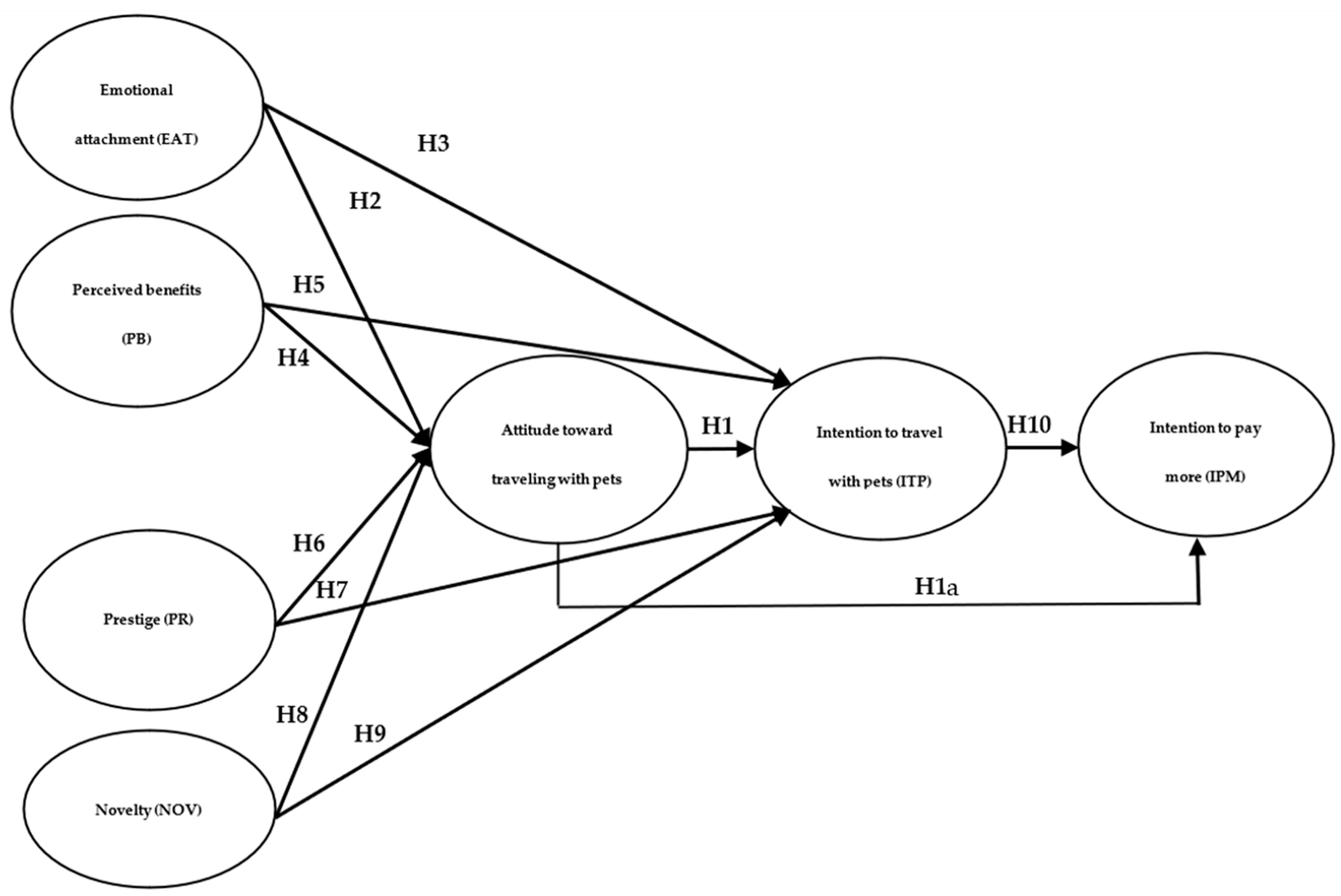

2.2. Conceptual Model and Research Hypothesis

2.2.1. Attitudes Toward Traveling with Pets

2.2.2. Emotional Attachment

2.2.3. Perceived Benefits

2.2.4. Prestige

2.2.5. Novelty

2.2.6. Intention to Pay More to Travel with Pets

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample

3.2. Measurement Scale

3.3. Analysis Technique

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Model

5. Discussion

5.1. Influence of EAT, PB, PR, and NOV in Attitudes Toward Traveling with Pets (ATP)

5.2. Influence of EAT, PB, PR, NOV, and ATP in the Intention to Travel with Pets

5.3. Influence of ATP and ITP in the Intention to Pay More to Travel with Pets (IPM)

6. Conclusions

6.1. Limitations of This Study

6.2. Implications

6.3. Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables/Author | Indicators |

|---|---|

| Emotional attachment (EAT), adapted from Kirillova et al. [57] | I feel guilty about leaving my pet(s) at home when I travel for leisure. I miss my pet(s) when I travel without them. When I travel without my pet(s), I feel worried about them. |

| Perceived benefits (PB), adapted from Kirillova et al. [57] | Pet admission policies at tourist destinations may influence me to consider taking my pet(s) on a leisure trip. Pet admission policies are the most important factor when booking accommodations if I travel with my pet(s). I believe that traveling with my pet(s) enhances my overall vacation experience. Thinking about traveling with my pet(s) makes me happy. |

| Prestige (PR), adapted from Tang et al. [11] | I can share my experience of traveling with my pet(s) with others. I can enjoy new travel experiences that differ from those who do not have pets. Traveling with my pet(s) may generate admiration and respect from others because of the experience. |

| Novelty (NOV), adapted from Tang et al. [11] | I can experience a sense of novelty when traveling with my pet(s). I can have a unique adventure when traveling with my pet(s). Traveling with my pet(s) helps me relax and makes my vacation more enjoyable. |

| Attitudes toward traveling with pets (ATP), adapted from Peng et al. [16] | For me, traveling with my pet(s) is desirable. For me, traveling with my pet(s) is pleasant. For me, traveling with my pet(s) is positive. For me, traveling with my pet(s) is fun. |

| Intention to travel with pets (ITP), adapted from Tang et al. [11] | I plan to travel with my pet(s) in the coming months. I would travel with my pet(s) in the next 12 months. I am looking forward to traveling with my pet(s) in the next 12 months. |

| Intention to pay more (IPM), adapted from Hultman et al. [53] | I am willing to have more expensive vacations if I travel with my pet. I am willing to pay more for my vacation if I knew the extra cost would guarantee a better experience for my pet. I am willing to pay more for pet-friendly accommodations compared to those that do not allow pets. |

References

- Taillon, J.; MacLaurin, T.; Yun, D. Hotel Pet Policies: An Assessment of Willingness to Pay for Travelling with a Pet. Anatolia 2015, 26, 89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Krier, L.; Josiam, B.; Kim, H. Understanding Consumer–Pet Relationship during Travel: A Model of Empathetic Self-Regulation in Canine Companionship. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2022, 23, 1088–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlakar, N.; Zupan, S. New Tourism Trend: Travelling with Pets or Pet Sitting at a Pet Hotel? In Contemporary Issues in Tourism; University of Maribor Press: Maribor, Slovenia, 2022; pp. 221–242. [Google Scholar]

- ASPCA Pet Statistics. Available online: https://www.aspca.org/helping-people-pets/shelter-intake-and-surrender/pet-statistics (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- PDSA. PDSA Animal Wellbeing Report; PDSA: Telford, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Statista La Industria de Las Mascotas En América Latina. Available online: https://es.statista.com/temas/11953/la-industria-de-las-mascotas-en-america-latina/ (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Hoy, L.S.; Stangl, B.; Morgan, N. The Social Behavior of Traveling with Dogs: Drivers, Behavioral Tendencies, and Experiences. J. Vacat. Mark. 2023, 31, 366–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, W.; Kim, S.; Baah, N.G.; Jung, H.; Han, H. Role of Physical Environment and Green Natural Environment of Pet-Accompanying Tourism Sites in Generating Pet Owners’ Life Satisfaction. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2023, 40, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, W.; Kim, S.; Baah, N.G.; Kim, H.; Han, H. Perceptions of Pet-Accompanying Tourism: Pet Owners vs. Nonpet Owners. J. Vacat. Mark. 2024, 40, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, N.; Cohen, S. Holidaying with the Family Pet: No Dogs Allowed! Tour. Hosp. Res. 2009, 9, 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Ying, T.; Ye, S. Chinese Pet Owners Traveling with Pets: Motivation-Based Segmentation. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 50, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillova, K.; Lee, S.; Lehto, X. Willingness to Travel With Pets: A U.S. Consumer Perspective. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2015, 16, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, T.; Tang, J.; Wen, J.; Ye, S.; Zhou, Y.; Li, F. Traveling with Pets: Constraints, Negotiation, and Learned Helplessness. Tour. Manag. 2021, 82, 104183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CADEM. Chile Que Viene: Mascotas; CADEM: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Diario Financiero. Pet Marketing: La Estrategia Que Capitaliza La Conexión Emocional Con Las Mascotas. Diario Financiero, 19 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, N.; Chen, A.; Hung, K.-P. Including Pets When Undertaking Tourism Activities: Incorporating Pet Attachment into the TPB Model. Tour. Anal. 2014, 19, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverland, M.B.; Farrelly, F.; Lim, E.A.C. Exploring the Dark Side of Pet Ownership: Status- and Control-Based Pet Consumption. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.-P.; Chen, A.; Peng, N. Taking Dogs to Tourism Activities. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2016, 40, 364–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Hung, K.; Wang, L.; Schuett, M.A.; Hu, L. Do Perceptions of Time Affect Outbound-Travel Motivations and Intention? An Investigation among Chinese Seniors. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.A.; Crompton, J.L. Quality, Satisfaction and Behavioral Intentions. Ann. Tour. Res. 2000, 27, 785–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, H.; Hamad, A.G.; Raed, H.; Maram, A.H. The Impact of Electronic Word of Mouth on Intention to Travel. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2019, 8, 1356–1362. [Google Scholar]

- Ferns, B.H.; Walls, A. Enduring Travel Involvement, Destination Brand Equity, and Travelers’ Visit Intentions: A Structural Model Analysis. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2012, 1, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.K.; Huang, K.C.; Nguyen, H.M. Elements of Destination Brand Equity and Destination Familiarity Regarding Travel Intention. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, H.; Sousa, B.; Carvalho, A.; Santos, V.; Lopes Dias, Á.; Valeri, M. Encouraging Brand Attachment on Consumer Behaviour: Pet-Friendly Tourism Segment. J. Tour. Herit. Serv. Mark. 2022, 8, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Joo, Y.; Jo, Y.; Jo, H.; Choi, H.; Yoon, Y. How Much Are You Willing to Pay When You Travel with a Pet? Evidence from a Choice Experiment. Curr. Issues Tour. 2024, 27, 2118–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behaviour Is Alive and Well, and Not Ready to Retire: A Commentary on Sniehotta, Presseau, and Araújo-Soares. Health Psychol. Rev. 2015, 9, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwinn, R.; Krajbich, I. Attitudes and Attention. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 86, 103892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurgiel, J.; Filipiak, K.J.; Szarpak, Ł.; Jaguszewski, M.; Smereka, J.; Dzieciątkowski, T. Do Pets Protect Their Owners in the COVID-19 Era? Med. Hypotheses 2020, 142, 109831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior: Frequently Asked Questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; McGinley, S.; Mao, Z.; Liu, X. Attributes of Pet-Friendly Hotels: What Matters to Consumers? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 123, 103944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malär, L.; Krohmer, H.; Hoyer, W.D.; Nyffenegger, B. Emotional Brand Attachment and Brand Personality: The Relative Importance of the Actual and the Ideal Self. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, F.R.; Voss, K.E. An Alternative Approach to the Measurement of Emotional Attachment. Psychol. Mark. 2014, 31, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Chan, J. Traveling with Pets: Designing Hospitality Services for Pet Owners/Parents and Hotel Guests. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 35, 4217–4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, R.; Woodside, A.G. Testing Theory of Planned versus Realized Tourism Behavior. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 905–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, M.C. Community Benefit Tourism Initiatives—A Conceptual Oxymoron? Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandža Bajs, I. Tourist Perceived Value, Relationship to Satisfaction, and Behavioral Intentions. J. Travel. Res. 2015, 54, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsujikawa, N.; Tsuchida, S.; Shiotani, T. Changes in the Factors Influencing Public Acceptance of Nuclear Power Generation in Japan Since the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Disaster. Risk Anal. 2016, 36, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tkatch, R.; Wu, L.; MacLeod, S.; Ungar, R.; Albright, L.; Russell, D.; Murphy, J.; Schaeffer, J.; Yeh, C.S. Reducing Loneliness and Improving Well-Being among Older Adults with Animatronic Pets. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 1239–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achabou, M.A.; Dekhili, S.; Codini, A.P. Consumer Preferences towards Animal-Friendly Fashion Products: An Application to the Italian Market. J. Consum. Mark. 2020, 37, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Wang, J.; Gao, F. Red Dog, Blue Dog: The Influence of Political Identity on Owner–Pet Relationships and Owners’ Purchases of Pet-Related Products and Services. Eur. J. Mark. 2024, 58, 2061–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Zhong, W.; Wang, J. To Dress up or Not: Political Identity and Dog Owners’ Purchase of Dog Apparels. Psychol. Mark. 2023, 40, 2118–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddle, E.; MacKay, J.R.D. Social Media Contexts Moderate Perceptions of Animals. Animals 2020, 10, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veblen, T.; Mills, C.W. The Theory of the Leisure Class; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2017; ISBN 9781315135373. [Google Scholar]

- Mitas, O.; Bastiaansen, M. Novelty: A Mechanism of Tourists’ Enjoyment. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 72, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skavronskaya, L.; Moyle, B.; Scott, N. The Experience of Novelty and the Novelty of Experience. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skavronskaya, L.; Moyle, B.; Scott, N.; Kralj, A. The Psychology of Novelty in Memorable Tourism Experiences. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2683–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.; Chen, A.; Peng, N. The Constraints for Taking Pets to Leisure Activities. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdas, M.; Mohamed, B. Impacts of Tourism on Environmental Attributes, Environmental Literacy and Willingness to Pay: A Conceptual and Theoretical Review. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 144, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frash, R.E.; DiPietro, R.; Smith, W. Pay More for McLocal? Examining Motivators for Willingness to Pay for Local Food in a Chain Restaurant Setting. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2015, 24, 411–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katt, F.; Meixner, O. A Systematic Review of Drivers Influencing Consumer Willingness to Pay for Organic Food. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 100, 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangl, B.; Prayag, G.; Polster, L. Segmenting Visitors’ Motivation, Price Perceptions, Willingness to Pay and Price Sensitivity in a Collaborative Destination Marketing Effort. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2666–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultman, M.; Kazeminia, A.; Ghasemi, V. Intention to Visit and Willingness to Pay Premium for Ecotourism: The Impact of Attitude, Materialism, and Motivation. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1854–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davras, Ö.; Durgun, S. Evaluation of Precautionary Measures Taken for COVID-19 in the Hospitality Industry During Pandemic. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2022, 23, 960–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Ruiz, J.E.; Aguilar-Rivero, M.; Aja-Valle, J.; Castaño-Prieto, L. An Analysis of the Demand for Tourist Accommodation to Travel with Dogs in Spain. Societies 2024, 14, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falk, R.F.; Miller, N.B. A Primer for Soft Modeling; Ohio University of Akron Press: Akron, OH, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 587–632. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Page, M.; Brunsveld, N. Essentials of Business Research Methods, 4th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 9780429203374. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, C.B.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M. A Critical Review of Construct Indicators and Measurement Model Misspecification in Marketing and Consumer Research. J. Consum. Res. 2003, 30, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. The Partial Least Square Approach to Structural Equation Modelling; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahawah, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Hult, T.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M.; Castillo, J.; Cepeda-Carrión, G.; Roldán, J.L. Manual de Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Springer Nature: Berlin, Germany, 2019; Volume 53. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, W.Y.; Choong, X.H.; Sam, T.H. The Mediating Role of Perceived Constraints between Human–Pet Relationships and Willingness to Travel with Pets: A Theoretical Framework. In Proceedings of the International Academic Symposium of Social Science 2022, Kota Bharu, Malaysia, 3 July 2022; MDPI: Basel, Switzerland, 8 September 2022; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age range | 18–24 | 87 | 35.0% |

| 25–34 | 94 | 37.8% | |

| 35–44 | 25 | 10.0% | |

| 45–54 | 22 | 8.8% | |

| Over 54 | 21 | 8.4% | |

| Sex | Male | 83 | 33.3% |

| Female | 166 | 66.7% | |

| Civil status | Single | 394 | 96.1% |

| Married | 16 | 3.9% | |

| Education | School | 28 | 11.2% |

| University (undergraduate) | 191 | 76.7% | |

| University (postgraduate) | 30 | 12% | |

| Family income | Up to 1 minimum wages | 61 | 24.5% |

| From 1 to 2 minimum wages | 55 | 22.0% | |

| From 2 to 3 minimum wages | 51 | 20.4% | |

| Greater than 3 minimum wages | 82 | 32.9% | |

| Variable | Item | Factor Loading | Cronbach Alpha | Rho_a | Composed Reliability (CR) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional attachment (EAT) | EAT1 | 0.911 | 0.890 | 0.931 | 0.819 | |

| EAT2 | 0.914 | 0.904 | ||||

| EAT3 | 0.889 | |||||

| Perceived benefits (PB) | PB1 | 0.825 | ||||

| PB2 | 0.655 | |||||

| PB3 | 0.805 | 0.885 | 0.904 | 0.912 | 0.636 | |

| PB4 | 0.773 | |||||

| PB5 | 0.868 | |||||

| PB6 | 0.873 | |||||

| Prestige (PR) | PR1 | 0.631 | ||||

| PR2 | 0.881 | 0.844 | 0.896 | 0.893 | 0.680 | |

| PR3 | 0.909 | |||||

| PR4 | 0.872 | |||||

| Novelty (NOV) | NOV1 | 0.913 | ||||

| NOV2 | 0.895 | 0.924 | 0.926 | 0.946 | 0.814 | |

| NOV3 | 0.919 | |||||

| NOV4 | 0.880 | |||||

| Attitudes toward traveling with pets (ATP) | ATP1 | 0.943 | ||||

| ATP2 | 0.937 | |||||

| ATP3 | 0.940 | 0.964 | 0.964 | 0.972 | 0.875 | |

| ATP4 | 0.936 | |||||

| ATP5 | 0.919 | |||||

| Intention to travel with pets (ITP) | ITP1 | 0.883 | ||||

| ITP2 | 0.932 | 0.879 | 0.879 | 0.925 | 0.805 | |

| ITP3 | 0.877 | |||||

| Intention to pay more (IPM) | IPM1 | 0.927 | ||||

| IPM2 | 0.954 | 0.931 | 0.932 | 0.956 | 0.879 | |

| IPM3 | 0.932 | |||||

| IPM4 | 0.872 |

| EAT | PB | PR | NOV | ATP | ITP | IPM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional attachment (EAT) | 0.905 | 0.692 | 0.573 | 0.634 | 0.568 | 0.354 | 0.602 |

| Perceived benefits (PB) | 0.622 | 0.798 | 0.704 | 0.839 | 0.833 | 0.541 | 0.812 |

| Prestige (PR) | 0.521 | 0.637 | 0.825 | 0.785 | 0.681 | 0.506 | 0.702 |

| Novelty (NOV) | 0.581 | 0.773 | 0.719 | 0.902 | 0.835 | 0.493 | 0.816 |

| Attitudes toward traveling with pets (ATP) | 0.532 | 0.784 | 0.644 | 0.791 | 0.935 | 0.541 | 0.807 |

| Intention to travel with pets (ITP) | 0.318 | 0.492 | 0.462 | 0.445 | 0.499 | 0.897 | 0.520 |

| Intention to pay more (IPM) | 0.554 | 0.744 | 0.644 | 0.758 | 0.765 | 0.470 | 0.937 |

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Path Coefficients | p-Values | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | ATP→ITP | 0.247 | 0.016 | Accepted * |

| H2 | EAT→ATP | −0.013 | 0.798 | Rejected |

| H3 | EAT→ITP | −0.032 | 0.700 | Rejected |

| H4 | PB→ATP | 0.416 | 0.000 | Accepted *** |

| H5 | PB→ITP | 0.231 | 0.045 | Accepted * |

| H6 | PR→ATP | 0.089 | 0.118 | Rejected |

| H7 | PR→ITP | 0.223 | 0.013 | Accepted * |

| H8 | NOV→ATP | 0.413 | 0.000 | Accepted *** |

| H9 | NOV→ITP | −0.071 | 0.571 | Rejected |

| H10 | ATP→IPM | 0.706 | 0.000 | Accepted *** |

| H1a | ITP→IPM | 0.118 | 0.015 | Accepted * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Veas-González, I.; Escobar-Farfán, M.; Carrión-Bósquez, N.; Bernal-Peralta, J.; García-Salirrosas, E.E.; Romero-Contreras, S.; Díaz-Díaz, C. Determinants of Pet-Friendly Tourism Behavior: An Empirical Analysis from Chile. Animals 2025, 15, 1741. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15121741

Veas-González I, Escobar-Farfán M, Carrión-Bósquez N, Bernal-Peralta J, García-Salirrosas EE, Romero-Contreras S, Díaz-Díaz C. Determinants of Pet-Friendly Tourism Behavior: An Empirical Analysis from Chile. Animals. 2025; 15(12):1741. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15121741

Chicago/Turabian StyleVeas-González, Iván, Manuel Escobar-Farfán, Nelson Carrión-Bósquez, Jorge Bernal-Peralta, Elizabeth Emperatriz García-Salirrosas, Sofía Romero-Contreras, and Camila Díaz-Díaz. 2025. "Determinants of Pet-Friendly Tourism Behavior: An Empirical Analysis from Chile" Animals 15, no. 12: 1741. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15121741

APA StyleVeas-González, I., Escobar-Farfán, M., Carrión-Bósquez, N., Bernal-Peralta, J., García-Salirrosas, E. E., Romero-Contreras, S., & Díaz-Díaz, C. (2025). Determinants of Pet-Friendly Tourism Behavior: An Empirical Analysis from Chile. Animals, 15(12), 1741. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15121741