Computed Tomography Evaluation of Frozen or Glycerinated Bradypus variegatus Cadavers: A Comprehensive View with Emphasis on Anatomical Aspects

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

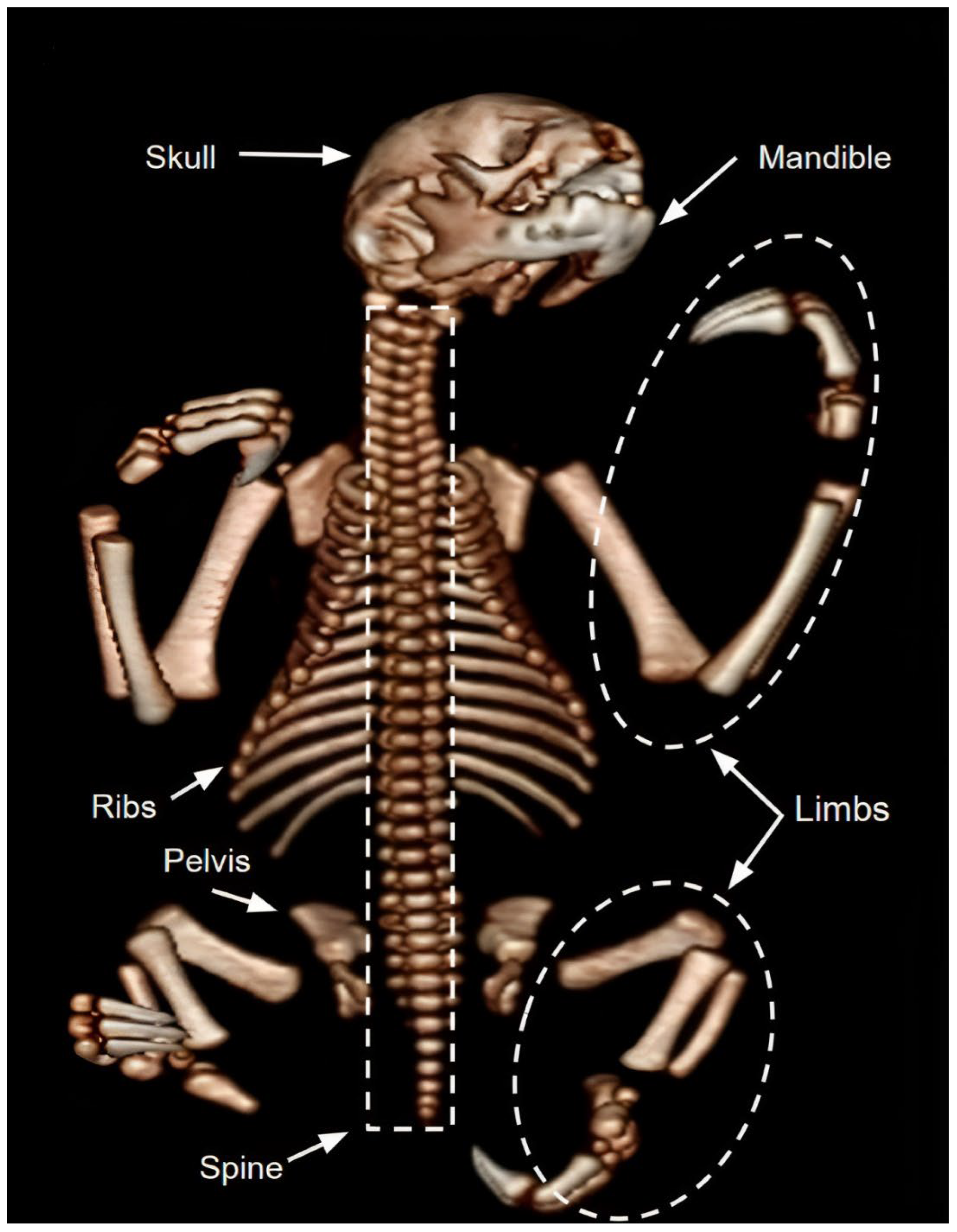

3.1. Tomographic Images of the Corpses

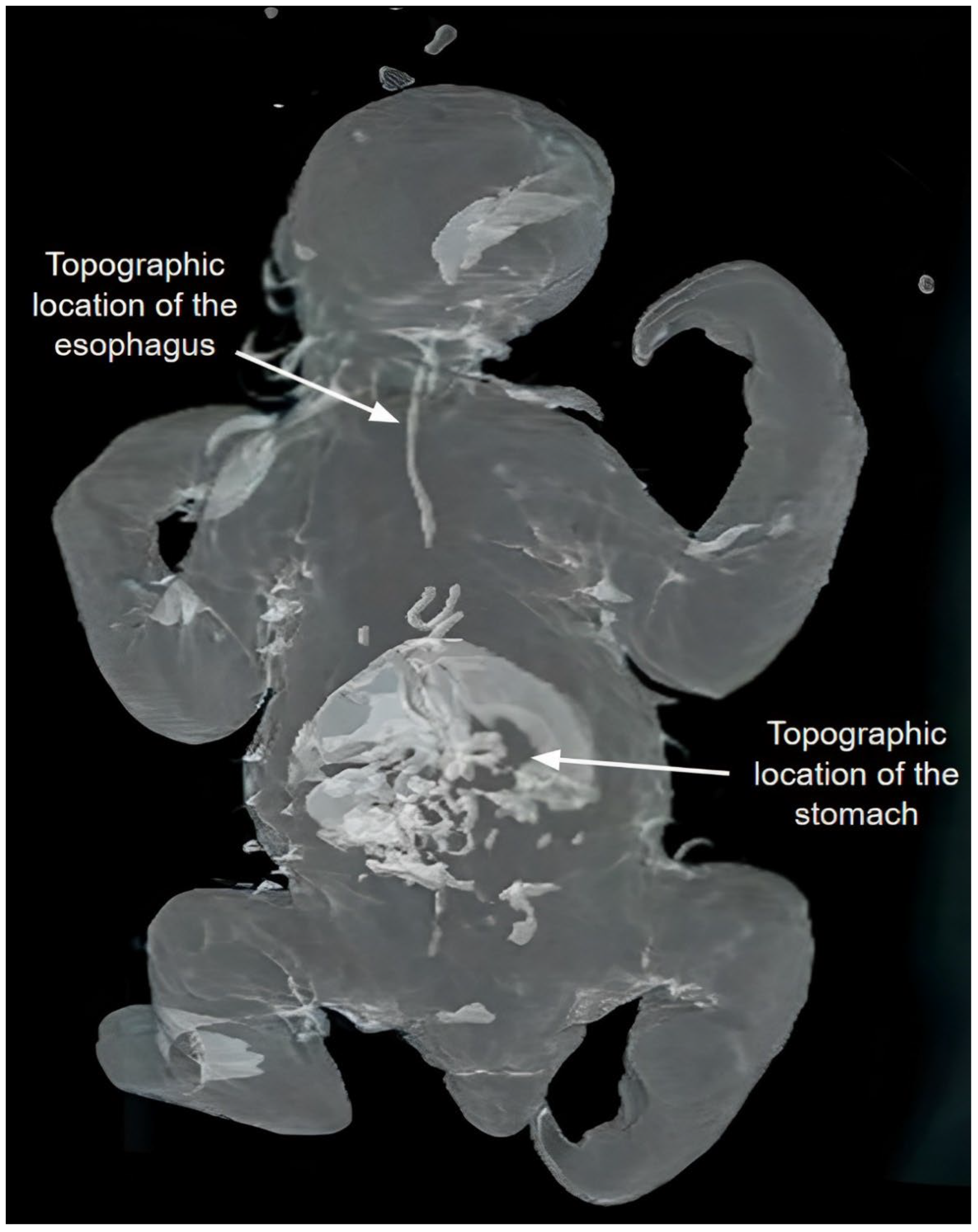

3.2. Tomographic Images of the Glycerinated Cadavers

3.3. Tomographic Images of the Frozen Cadaver with IV Contrast

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dixon, J.; Lam, R.; Weller, R.; Manso-Díaz, G.; Smith, M.; Piercy, R.J. Clinical application of multidetector computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging for evaluation of cranial nerves in horses in comparison with high resolution imaging standards. Equine Vet. Educ. 2017, 29, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yitbarek, D.; Dagnaw, G.G. Application of advanced imaging modalities in veterinary medicine: A Review. J. Vet. Med. Res. 2022, 13, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toma, H.S.; Barreto, J.V.P.; Amude, A.M.; Toma, C.D.M.; Santos, J.P.V.; Schneider, L.O.; Néspoli, P.E.B.; Pertile, S.F.N.; Cunha Filho, L.F.C. Clinical, tomographic, and postmortem aspects of a rare congenital Dicephalus Monauchenos Iniodymus in a Nelore calf produced in vitro from Brazil—Case report. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2021, 73, 1105–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, O.P. Three-dimensional computed tomography reconstructions: A tool for veterinary anatomy education. Ann. Med. Surg. 2021, 67, 102497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, J.R.; Rezende, L.C.; Barbosa, A.S.; Carvalho, P.; Lima, N.E.; Carvalho, A.A. Economic, human and environmental health benefits of replacing formaldehyde in the preservation of corpses. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 145, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, G.; Andreola, S.; Bilardo, G.; Boracchi, M.; Tambuzzi, S.; Zoja, R. Technical note—Stabilization of cadaveric corified and mummified skin thanks to prolonged temperature. Int. J. Legal. Med. 2020, 134, 1797–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliappan, A.; Motwani, R.; Gupta, T.; Chandrupatla, M. Innovative cadaver preservation techniques: A systematic review. Maedica 2023, 18, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad, J.R.J.; Mohamad, J.R.J.; González-Rodríguez, E.; Arencibia, A.; Déniz, S.; Carrascosa, C.; Encinoso, M. Anatomical description of loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta) and green iguana (Iguana iguana) skull by three-dimensional computed tomography reconstruction and maximum intensity projection images. Animals 2023, 13, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, F.M.A.M.; Bete, S.B.S.; Inamassu, L.R.; Mamprim, M.J.; Schimming, B.C. Anatomy of the skull in the capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) using radiography and 3D computed tomography. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 2020, 49, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Fujiwara, R.; Iseri, T.; Nagahama, S.; Kakishima, K.; Kamata, M.; Mochizuki, M.; Nakagawa, T.; Sasaki, N.; Nishimura, R. Distribution of contrast medium epidurally infected at thoracic and lumbar vertebral segments. J. Vet. Med. 2013, 75, 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuoran, M.A.; Shang, M.; Yue, J.; Alcazar, C.; Zhong, Y.; Doyle, T.C.; Dai, H.; Ngan, F. Nearinfrared IIb fluorescence imaging of vascular regeneration with dynamic tissue perfusion measurement and high spatial resolution. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1803417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radulova-Mauersberger, O.; Weitz, J.; Riediger, C. Vascular surgery in liver resection. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2021, 406, 2217–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taube, E.; Keravec, J.; Vié, J.; Duplantier, J. Reproductive biology and postnatal development in sloths, Bradypus and Choloepus: Review with original data from the field (French Guiana) and from captivity. Mamm. Rev. 2008, 31, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Vásquez, L.; Meza, M.; Plese, T.; Moreno-Mora, S. Activity patterns, preference and use of floristic resources by Bradypus variegatus in a tropical dry forest fragment, Santa Catalina, Bolívar, Colombia. Edentata 2010, 11, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justo, M.; Cury, F.S.; Godoy, S.H.S.; Fernandes, A.M.; Martins, D.S.; Ambrósio, C.E. Microbiological evaluation of anatomical organs submitted to glycerinization and freeze-drying techniques. Transl. Res. Anat. 2016, 3, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Committee on Veterinary Gross Anatomical Nomenclature. Nomina Anatomica Veterinaria, 6th ed.; Editorial Committee: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Hannover, Germany; Ghent, Belgium; Columbia, Indiana, 2017; 178p. [Google Scholar]

- Clauss, M.; Trümpler, J.; Ackermans, N.L.; Kitchener, A.C.; Hantke, G.; Stagegaard, J.; Takano, T.; Shintaku, Y.; Matsuda, I. Intraspecific macroscopic digestive anatomy of ring-tailed lemurs (Lemur catta), including a comparison of frozen and formalin-stored specimens. Primates 2021, 62, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karam, R.G.; Cury, F.S.; Ambrósio, C.E.; Mançanares, C.A.F. Gliceryn can replace formaldehyde for anatomic conservation. Pesq. Vet. Bras. 2016, 36, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins-Costa, C.; Nunes, T.C.; Anjos-Ramos, L. Anatomo-comparative study of formaldehyde, alcohol, and saturated salt solution as fixatives in Wistar rat brains. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 2022, 51, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banzato, T.; Russo, E.; Toma, A.; Palmisano, G.; Zotti, A. Evaluation of radiographic, computed tomographic, and cadaveric anatomy of the head of boa constrictors. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2011, 72, 1592–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawalilak, L.T.; Tucker, R.L.; Greene, S.A. Use of contrast-enhanced computed tomography to study the cranial migration of a lumbosacral injectate in cadaver dogs. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2015, 56, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, L.; Arencibia, A.; Rizkallal, C.; Blanco, D.; Farray, D.; Diaz-Bertrana, M.L.; Carrascosa, C.; Jaber, J.R. Computed tomographic imaging of the brain of normal neonatal foals. Arch. Med. Vet. 2015, 47, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrivani, P.V.; Percival, A. Anatomic study of the canine bronchial tree using silicone casts, radiography, and CT. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2023, 64, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, N.E.O.; Amorim, M.J.A.A.L.; Albuquerque, P.V.; Miranda, M.E.L.C.; Alcântara, S.F.; Andrade, G.P.; Mesquita, E.P.; Bittencourt, T.Q.M.; Amorim Júnior, A.A. Identification of the tributary branches of the hepatic portal vein in the common sloth, Bradypus variegatus Schinz, 1825 (Pilosa: Bradypodidae). Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2022, 74, 825–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velroyen, A.; Bech, M.; Zanette, I.; Schwarz, J.; Rack, A.; Tympner, C.; Herrler, T.; Staab-Weijnitz, C.; Braunagel, M.; Reiser, M.; et al. X-ray phase-contrast tomography of renal ischemia-reperfusion damage. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e109562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilmore, D.P.; Costa, C.P.; Duarte, D.P.F. Sloth biology: An update on their physiological ecology, behavior and role as vectors of arthropods and arboviruses. Braz. J. Med. Biol. 2021, 34, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca Filho, L.B.; Albuquerque, P.V.; Alcântara, S.F.; Nascimento, J.C.S.; Miranda, M.E.L.C.; Andrade, G.P.; Pereira, L.B.S.; Menezes, F.B.A.; Mesquita, E.P.; Amorin, M.J.A.A.L. Macroscopic description of small and large intestine of the Sloth Bradypus variegatus. Acta Sci. Vet. 2018, 46, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, C.R. Veterinary diagnostic imaging: Probability, accuracy and impact. Vet. J. 2016, 215, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, E.Y.E.; Soares, P.C.; Mello, L.R.; Freire, E.C.B.; Lima, A.R.; Giese, E.G.; Branco, E. Sloths (Bradypus variegatus) as a polygastric mammal. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2020, 84, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clauss, M. The potential interplay of posture, digestive anatomy, density of ingesta and gravity in mammalian herbivores: Why sloths do not rest upside down. Mamm. Rev. 2004, 34, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drees, R.; Dennison, S.E.; Keuler, N.S.; Schwarz, T. Computed tomographic imaging protocol for the canine cervical and lumbar spine. Vet. Radiol. Ultrasound 2009, 50, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, U.; Irmer, M.; Augsburger, H.; Ohlerth, S. Computed tomography of the abdomen in Saanen goats: III. kidneys, ureters and urinary bladder. Schweiz. Arch. Tierheilk. 2011, 153, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cunha, M.S.e.; Albuquerque, R.d.S.; Campos, J.G.M.; Monteiro, F.D.d.O.; Rossy, K.d.C.; Cardoso, T.d.S.; Carvalho, L.S.; Borges, L.P.B.; Domingues, S.F.S.; Thiesen, R.; et al. Computed Tomography Evaluation of Frozen or Glycerinated Bradypus variegatus Cadavers: A Comprehensive View with Emphasis on Anatomical Aspects. Animals 2024, 14, 355. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14030355

Cunha MSe, Albuquerque RdS, Campos JGM, Monteiro FDdO, Rossy KdC, Cardoso TdS, Carvalho LS, Borges LPB, Domingues SFS, Thiesen R, et al. Computed Tomography Evaluation of Frozen or Glycerinated Bradypus variegatus Cadavers: A Comprehensive View with Emphasis on Anatomical Aspects. Animals. 2024; 14(3):355. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14030355

Chicago/Turabian StyleCunha, Michel Santos e, Rodrigo dos Santos Albuquerque, José Gonçalo Monteiro Campos, Francisco Décio de Oliveira Monteiro, Kayan da Cunha Rossy, Thiago da Silva Cardoso, Lucas Santos Carvalho, Luisa Pucci Bueno Borges, Sheyla Farhayldes Souza Domingues, Roberto Thiesen, and et al. 2024. "Computed Tomography Evaluation of Frozen or Glycerinated Bradypus variegatus Cadavers: A Comprehensive View with Emphasis on Anatomical Aspects" Animals 14, no. 3: 355. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14030355

APA StyleCunha, M. S. e., Albuquerque, R. d. S., Campos, J. G. M., Monteiro, F. D. d. O., Rossy, K. d. C., Cardoso, T. d. S., Carvalho, L. S., Borges, L. P. B., Domingues, S. F. S., Thiesen, R., Thiesen, R. M. C., & Teixeira, P. P. M. (2024). Computed Tomography Evaluation of Frozen or Glycerinated Bradypus variegatus Cadavers: A Comprehensive View with Emphasis on Anatomical Aspects. Animals, 14(3), 355. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani14030355