1. Introduction

Intergenerational justice entitles the maximum retention of Earth’s biodiversity [

1]. This review focuses on three core themes: the need and potential of reproduction biotechnologies, biobanks, and conservation breeding programs (RBCs) to satisfy sustainability goals; the technical state and current application of RBCs; and how to achieve the future potentials of RBCs in a rapidly evolving environmental and cultural landscape. There are increasing rates of decline and extinction in amphibian species due to widespread anthropogenic damage to global ecosystems [

2,

3,

4]. This crisis demands proactive and innovative strategies to perpetuate amphibian diversity. The 2022 United Nations COP 15, “Ecological Civilisation: Building a Shared Future for All Life on Earth”, through the protection of 30% of Earth’s terrestrial area [

5], and COP 28, in mitigating the effects of the climate crisis [

6], focus on sustainably managing the biosphere. Unfortunately, the climate crisis alone [

3] will inevitably result in profoundly modifying ecosystems over the coming decades, leading to a disastrous cascade of species population declines and extinctions [

3,

4]. Consequently, a rapid increase in the number of amphibian species reaching extinction in the wild can be expected [

2,

3,

4].

The development and application of RBCs can achieve the biodiversity conservation goals of COP 15 and COP 28. RBCs can safely, securely, and economically maintain endangered and critically endangered species and proliferate genetically varied individuals for release in field conservation programs [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. However, the full potential of RBCs lies in perpetuating species through the restoration of individuals solely from biobanked cells or tissues [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. RBCs’ economical and efficient use [

13,

14] is particularly valuable for species whose natural habitats will be lost and otherwise neglected [

22,

23,

24].

The global establishment of amphibian RBCs requires developing networks to support facilities, particularly in the Global South and other countries with the highest amphibian diversity [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Two fundamental principles form the foundation of non-partisan multi-stakeholder engagement: firstly, the increasing assertion of the Global South and other developing countries in a multipolar geopolitical landscape [

5,

28], and secondly, the growing significance of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and the public in species conservation [

25]. We use the term developing countries with the caveat that our use of the term refers to modern eco-friendly development to provide human well-being and environmental sustainability rather than GDP growth as the critical indicator of development [

5,

28]. Following these principles can build RBCs through collaborations with regional, national, and international programs, an approach that enhances the global effort to protect amphibian diversity and contributes to the stewardship of local communities in RBC conservation initiatives [

6,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

Amphibians provide an optimal vertebrate class to implement and exemplify species management through RBCs. Cultural and political advantages of amphibian RBCs include amphibians’ popularity as conservation ambassadors and amenability to regional community programs, including ecosystem protection [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. Biological, technical, and economic factors include amphibians’ small size, relative ease of care compared to megafauna, high fecundity, and proven amenability for RBCs [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. This amenability fits well with the One Plan Approach to Conservation [

35], which integrates the management of a species’ metapopulation [

36] through in situ with ex situ approaches, including RBCs, to maintain or restore genetic variation [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

Since the turn of the millennium, RBCs have perpetuated amphibian species’ genetic diversity and allelic variation [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. This ability has led to well-financed programs in Australia [

37] and the USA [

38], with nascent programs in Global South countries with very high amphibian diversity, including Ecuador [

39], Mexico [

40], Panama [

12], and Papua New Guinea [pers comm] lacking sufficient financial support. Consequently, the demonstrated capability of amphibian RBCs to reduce costs and increase the reliability of

global ex-situ and in-situ species management still needs to be fulfilled [

2,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

22,

41,

42].

We explore these potentials through the sections (1) Regional targeting of amphibian RBCs, (2) Species prioritisation for amphibian RBCs, (3) Maintaining genetic diversity, (4) Contextualising amphibian RBCs, (5) Amphibian conservation breeding programs (CBPs), (6) Biobanking facilities, (7) Financial support, (8) Cultural engagement, and (9) The road ahead, where we argue that the full potential of amphibian RBCs requires a democratic, globally inclusive organisation that focuses on developing facilities in the regions with the highest amphibian diversity.

2. Regional Targeting of Amphibian RBCs

Regional targeting of amphibian RBCs depends on biogeographical species richness and threats, including habitat loss and global heating, prey loss and increased predation, illegal trade, and pathogens and parasites.

The highest amphibian diversities are found in regions with long geological periods, amenable climates, and varied geomorphology, including the isolating mechanisms of islands, mountains, and watersheds to promote speciation [

43,

44]. In 2023, the AmphibiaWeb database catalogued 8713 amphibian species. Of these, 7677 are frogs and toads, 815 are newts and salamanders, and 221 are caecilians. The ten top countries in declining order of amphibian species richness were Brazil (1176 sp.) Colombia (832 sp.), Ecuador (688 sp.), Peru (672 sp.), China (607 sp.), India (454 sp.), Papua New Guinea (426 sp.), Mexico (424 sp.), Madagascar (412 sp.), Indonesia (394 sp.), and Venezuela (365 sp.) [

45].

The ranges of the three orders of amphibians, anurans (frogs and toads), salamanders (Caudata), and caecilians (Gymnophiona) are not sympatric. Major biogeographical areas with high anuran diversity include Southeast Asia, Africa, Southeast North America, and Central and South America [

43,

44,

45], with most new species discoveries in the tropical regions of South America, India/Asia, Indo-Pacific, and Africa [

44]. Salamanders and caecilians are more restricted in distribution than anurans. Among the ten salamander families, nine are predominately temperate, with a centre of diversity in Southeast North America. However, species of the tenth family, the highly threatened Plethodontidae, are mainly tropical and include 228 of the 555 currently described salamander species [

46,

47,

48,

49]. Half of these species are in the Mesoamerican Highlands of Mexico or South and Central America, with many new species being discovered in Brazil [

49]. The distribution of the basal salamander family Cryptobranchoidea extends from Northeast Asia to Eastern North America [

50]. Caecilians inhabit Central and South America, the South Asian tropics, and Eastern and Western Africa, with an intriguing absence in Central Africa. The conservation status of many caecilian species is unknown due to their fossorial habitats [

47,

48,

51].

Habitat loss is the primary driver of amphibian declines, affecting ~65% of all amphibian species and reaching alarming levels of ~90% for threatened species [

52,

53]. Targeting only 2% of the global terrestrial area would protect over 80% of salamander and 65% of caecilian and anuran phylogenetic diversity [

54]. Much amphibian species diversity also exists in a small percentage of bioregions. For example, the small country of Ecuador is home to 8% of amphibian species, half of which are endemic [

55]. Island regions with high anuran endemicity include Melanesia, with 15% of species in 0.7% of the global terrestrial area [

56], and Madagascar, with 5% of species in 0.4% of the global terrestrial area [

57]. Many amphibian species also depend on mountain habitats with a high altitudinal range [

58,

59], and many of these species will become extinct in the wild due to unachievable needs for altitudinal migration due to global heating to a likely 2.5 °C or more [

3,

4,

60,

61,

62].

A significant threat to amphibians is reduced prey availability, where insect populations and their diversity are rapidly declining [

63,

64]. Modifications to aquatic ecosystems in flow and water quality can produce changes in the density and composition of biota that could affect tadpole growth and survival [

65]. Exotic species are an increasing driver of species declines and extinctions [

66], where complicated interactions can occur between species within ecosystems [

67]. For instance, the invasive Cane toad

Rhinella marina significantly affects some Australian native frog populations via rarefication through direct predation and competition, with counteracting of these effects by

R. marina toxicity to frog populations in general [

68].

Commercialising natural biological resources can yield conservation benefits through increased cultural engagement and habitat management or harm through over-exploitation. The commercial amphibian trade for food or companion animals includes thousands of individuals and hundreds of species [

69,

70]. To our knowledge, no amphibian species have become extinct through overcollection for trade. However, assessing the sustainability of this trade is challenging due to difficulties in tracking [

70], exacerbated by insufficient taxonomic and threatened species data [

71]. Unfortunately, CITES regulations are not sympathetic toward the extraordinary need of private carers for the international trade of listed species to support their CBPs. Meanwhile, criminal and irresponsible individuals and organisations profit through illegal trade [

69].

Significant threats to amphibian survival are pathogens, including

Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), which spread globally in the early to mid-20th century, causing the extinction of ~2% of amphibian species and infecting ~7% of species, as was found in ~70% of surveyed countries [

72,

73]. Inter-regional transmission of

B. dendrobatidis can occur through keratinous skin on crayfish, nematode worms [

73], fish [

74,

75], and migratory birds’ feet [

76]. Emerging threats from pathogens include

B. salamandrivorans, confined to Eurasia but threatening the high salamander diversity of the Americas [

77], and through global heating, which increases the ranges of amphibian parasites [

50,

78,

79]. Safeguarding amphibians from emerging pathogens relies on factoring in pathogens, sound management, and control rather than elimination [

80,

81,

82].

3. Species Prioritisation for Amphibian RBCs

Significant sources for species prioritisation for amphibian RBCs through endangerment status are the Amphibia Web [

45], IUCN Red List [

2], and the Amphibian Ark [

42]. A different perspective is through The Royal Zoological Society of London, Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered (EDGE), which prioritises species based on phylogenetic significance [

83,

84]. RBCs can also be prioritised for amphibians displayed in zoos [

85], in the general community as companion animals that exhibit attractive colours or patterns [

25], or for species of cultural significance to traditional communities [

25,

86].

The term “Threatened Species” is often used generically concerning RBCs [

87]. However, the Threatened Species category includes Vulnerable (VU), Endangered (EN), and Critically Endangered (CE) species [

2]. Vulnerable species are not thematic targets of RBCs, as their management focus should be field conservation programs, including habitat protection or replacement, repopulation, translocation, and augmentation (

Table 1, [

33,

35,

88,

89]).

Database integration between all components of RBCs is essential to provide contemporary and accurate information about targeted species [

90,

91,

92]. Over half of the amphibian species on the IUCN Red List have outdated assessments [

2], with this deficiency particularly applying to regions with high amphibian diversity [

2,

47,

49] and caecilians [

48,

51]. Besides this deficiency, the IUCN Red List does not offer a functional list of species recommended for CBPs, termed “Ex-situ Conservation” [

Table 1]. Instead, species recommended for CBPs are mostly Least Concern (LC) species.

A framework for evaluating the relevance and impact of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species was published in 2020 [

93] but has yet to be implemented. Unfortunately, the annual funding of the IUCN Red List and other significant databases for amphibian sustainability is inadequate and only represents a minuscule amount of global biospheric sustainability funding. Adequate financial support for these databases and associated taxonomy would support amphibian sustainability and help save species in other taxa.

Palacio et al. [

94] also showed that inaccuracies in the Aves Red List hampered rather than supported their conservation. Furthermore, they found that Red List specialist groups did not respond to feedback and needed more transparency, and the Red List rules and guidelines were either not followed or misused.

The Amphibian Ark was established through collaboration between the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA), the IUCN SSC Conservation Planning Specialist Group (CPSG), and the IUCN SSC Amphibian Specialist Group (ASG [

88]). The AArk provides contemporary information, a newsletter, seed grants for CBPs, and regional assessments for CBPs listing over 400 EN and CE species, with almost 100% recommended for RBCs [

42]. However, the AArk and the IUCN prioritisation for RBCs need improvement to ensure the long-term sustainability of amphibian biodiversity. For instance, besides their endangerment status [

2], Amphibian Ark prioritisation of species suitability for CBPs also includes other criteria [

22]:

Biodiversity loss is acceptable in principle. However, many consider that it is ethically unacceptable for amphibian species to be pre-emptively doomed to extinction due to neglect through policy [

95]. Furthermore, in line with global environmental standards, the USA and Australian governments have adopted a no-species-lost policy [

96].

Candidate species for CBPs need an evidenced potential for eventual repopulation in the wild [

97,

98]. However, this mandate could result in the neglect of many species as ecosystems are predictably modified or destroyed. Furthermore, it is challenging to predict the future potential survival of species in the wild due to adaptation to pathogens [

99], through amelioration [

80,

82], or via release programs for Bd-prone species [

100,

101].

The number of species in CBPs is limited by the need for large populations of each species [

97,

102]. However, reproduction technologies and biobanks can dramatically reduce the required populations for a species in a CBPs to a few females [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. RBCs through biobanked sperm can restore genetic variation even in highly domesticated varieties of amphibians [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Furthermore, the capacities of CBPs are increasing through international and regional initiatives [

103,

104] and potentially through the vast potential of private caregivers [

25].

A species’ captive care requirement should be known before establishing a CBP. However, most amphibians are amenable to captive care in simulacrums of their natural habitats or even entirely artificial habitats, as evidenced by many detailed captive care protocols and the successful reproduction of an increasing number of species [

25,

105,

106]. If reproduction proves challenging, hormonal stimulation can assist in the reproduction of any species [

8,

9,

11].

A CBP for a species must ensure sufficient funding for its anticipated length. However, the time frame of CBPs for the species most in need cannot be predicted and could extend for years, decades, or indefinitely [

107]. Many of the most significant CBPs still need to satisfy this funding requirement and have initially relied on donations and volunteers without any assurance of long-term funding [

108,

109].

Furthermore, the IUCN Red List [

2] species recommendations as “Genome Resource Banking” [

Table 2] is also not supportive of amphibian RBCs with a bias toward species of Least Concern (LC) that do not need any proactive management and with only 4.3% of EN or CE species listed as being in need of RBCs.

We provide a triage to direct resources toward species based on their endangerment status:

Triage 1. Vulnerable species. These are species with declining populations whose survival in the wild could be ensured through habitat protection or in rehabilitated, restored, or newly created habitats. If required, head-starting is the best option to produce numerous progenies for release (

Table 1).

Triage 2. Endangered or Critically Endangered species with remaining habitat with a reasonable possibility of population maintenance in the wild. RBC priorities are maintaining adequate broodstock numbers to produce numerous genetically diverse progeny if needed for release (

Table 1). These are the costliest RBCs because of the high broodstock numbers needed to produce progeny for release [

107], especially when providing assisted gene flow [

110].

Triage 3. Critically endangered species with predicted irrecoverable habitat loss. RBCs are critical, with species’ genetic diversity perpetuated through biobanked sperm. The cost of RBCs is moderate with these CBPs in institutions [

13,

14], and very low when conducted by private caregiver CBPs [

25].

4. Maintaining Genetic Diversity

Maintaining a species’ genetic diversity or allelic variation in RBCs or small wild populations is expensive and inefficient without utilising biobank sperm. A minimum of 20 CBP founders captures 97.5% of heterozygosity [

107]. Then, depending on the species’ generation time and lifespan, maintaining most heterozygosity for periods of only 10–25 years, without support from biobanked sperm, requires populations of 80–1500 individuals [

107,

111]; see Amphibian Ark calculator [

112].

However, a minimum population of 40 or more founders is preferable to capture 99.5%+ of genetic diversity and increase the probability of capturing allelic variation to enable adaptability in the wild [

110]. Founders can be represented by cryopreserved sperm [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

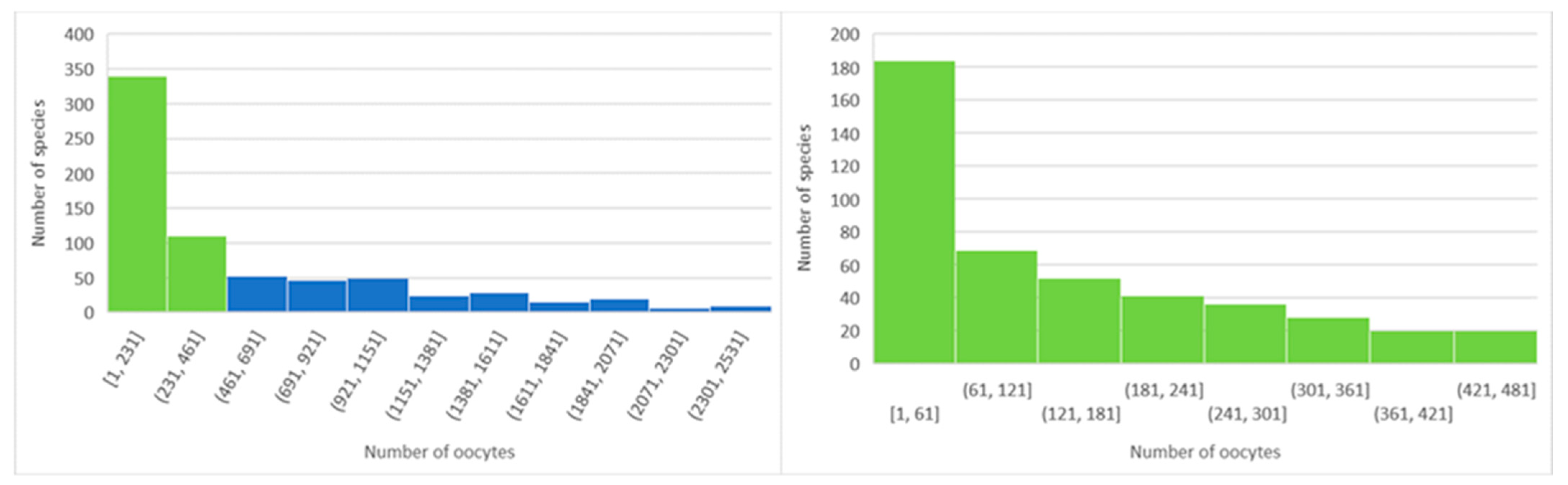

113]; however, dependent on the species fecundity, the number of females needed depends on the provision of progeny for releases (

Figure 1, [

114]).

An extraordinary long-term potential for amphibian RBCs is perpetuating species that would otherwise become extinct in the wild. However, RBCs can also help maintain the genetic diversity and allelic variation of species with very low populations in the wild through assisted gene flow (AGF) [

87,

115]. The advantages of AGF for wild populations depend on large numbers of introduced individuals providing highly advantageous alleles. However, AGF can be ineffective or even detrimental, and dependent on a wide range of factors, including natural selection, genetic drift, and outbreeding depression [

116,

117,

118,

119,

120,

121,

122,

123]. To avoid outbreeding depression with fragmented populations by AGF, the pooled genetic diversity from the core metapopulation should be provided. Isolated subpopulations should only be subject to AGF using their unique genetic diversity [

107,

110].

More research is needed on amphibians and other taxa to evidence the risks of AGF and the contribution of low genetic diversity or allelic variation to population declines. However, most species appear to reach extinction before genetic factors influence them [

121,

122], while many species have thrived with low genetic variation [

21]. Furthermore, threats by major environmental stressors such as global heating have no known genetic basis to address them. Nevertheless, considering these uncertainties, ASG conducted with due diligence could benefit small fragmented or relict amphibian populations.

In conclusion, once the potential advantages of AGF to a population are evidenced, the number of released individuals at each life stage must be highly proportional to the demographic target population at that life stage. The release of large numbers of individuals in early life stages enables natural selection to maximise the potential for success. The release of individuals from CBPs to bolster population levels of small relict populations will automatically correspond to AGF [

100,

101,

123].

5. Contextualising Amphibian RBCs

Current amphibian reproduction biotechnologies include stimulating reproduction and the collection of sperm or oocytes, the storage of sperm for indefinite periods, and using oocytes and sperm for artificial fertilisation. These highly advanced techniques significantly reduce the number of live individuals required for CBPs, perpetuate genetic diversity and allelic variation, and can provide numerous progenies for release [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Ongoing generations of anurans and salamanders have been produced from cryopreserved sperm [

124,

125,

126]. However, the conservation crisis continues to deepen and demands the perpetuation of otherwise neglected species solely in biobanks. The satisfaction of this need should now be the focus of RBC biotechnical research [

7,

18,

19].

Amphibian reproduction biotechnologies for conservation began through hormonal stimulation of reproductive behaviour and spawning in Russia between 1986–1989 [

127,

128]. Cryopreserved anuran testicular sperm was then used to fertilise oocytes at the turn of the 21st century in Russia [

129,

130] and Australia [

131] with hormonal sperm was used in Russia in 2011 [

132]. The potential of various RBCs, including cloning, to maintain amphibian genetic diversity was presented in 1999 [

7]. Nonetheless, sperm-based RBCs remain the primary method for maintaining genetic diversity [

133]. However, the full potential of RBCs needs to focus on developing heterocytoplasmic cloning and other somatic cell techniques [

18,

19]. Assisted gene flow has recently been explored through programs in the USA and Australia [

87,

134].

Figure 2 shows a timeline of some significant achievements of RBCs with corresponding references and other milestones in the research, and the application of RBCs, as listed in

Appendix A.

6. Amphibian Conservation Breeding Programs [CBPs]

Amphibian conservation breeding programs (CBPs) are a significant component of RBCs that can be in range or out of range, in well-financed institutional programs such as university research groups and zoos [

31,

33], or be self-supporting through NGOs and their members, volunteers, ecotourism, and trade [

25,

30]. CBPs supported by cryopreserved sperm can guarantee species survival through a range of field species programs (

Table 3, [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

135]), along with fostering conservation research, education, and community engagement [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33].

The literature concerning CBPs uses a confusing variety of terminology. We encourage using the IUCN conventional term Conservation Breeding Programs [CBPs; Wren pers comm.]. We use the terms “in range” and “out of range” for CBPs, rather than in situ and ex situ. We provide a tabulation of a standard terminology for field programs associated with RBCs (

Table 3).

Citizen conservation through private caregivers and their NGOs provides significant potential for CBPs. Private caregivers already maintain many threatened species and could support many more through community engagement, habitat protection, rehabilitation, or restoration. Increasing support for private caregivers and their NGOs and institutional RBCs focused on species in urgent need of care could help conserve all recommended species [

25].

Citizen conservation turns citizens into practising conservationists: raising awareness, motivating people to get directly involved, and bringing together different areas of expertise to significantly contribute to biodiversity conservation. Citizen conservation unites private amphibian caregivers and professional conservationists in an inclusive and robust societal approach to support proactive amphibian sustainability. Zoo-based and other institutional CBPs for amphibians [

8] are limited by breeding space and staff and tend to focus on charismatic or iconic species [

31]. However, private caregivers (CBPs) offer almost unlimited opportunities to expand CBP capacities [

25] while gaining and sharing knowledge, which is a win–win situation for the sustainable management of amphibians [

140].

Greater incorporation of the vast global potential of private caregivers could lead to CBPs for threatened species at significantly reduced costs, along with building public and political support, both within and outside the species’ native range, for instance, the Responsible Herpetological Project [

141]. Private caregivers have the facilities, time, passion, and knowledge to care for and reproduce threatened species (

Table 4,

Figure 2, [

117,

140,

141,

142]). A vast opportunity for species perpetuation exists where private caregivers’ collections as domestic varieties can later re-establish a species’ genetic diversity through biobanked sperm [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. The success demonstrated by private caregivers in reproducing numerous species of anurans and salamanders underscores their excellent standards of care and potential to make significant contributions to CBPs if provided with the opportunity (

Table 4,

Figure 3, [

140,

141,

142]).

A common misconception is the exclusion of private caregiver CBPs because of quarantine issues. Criteria for institutional CBPs are strict quarantine facilities and protocols to prevent pathogens from spreading by multiple staff working in the facility or from the external environment and biota. However, these protocols are inherent in private caregiver CBPs as they are under devoted care in an isolated domestic urban environment. Furthermore, all releases are subject to quarantine and pathogen screening, and the main pathogen threat of

Batrachochytrium sp. has been treatable since 2012 [

62]. The key to safeguarding amphibians amidst emerging infectious diseases lies in factoring in pathogens rather than attempting elimination [

59,

62].

Examples of the contribution of private caregiver CBPs to amphibian conservation include direct zoo collaborations, NGOs, and individual initiatives [

141,

142]. The amphibian conservation program at Cologne Zoo, German Republic, is a global focus and model for developing CBPs for amphibians [

143]. This CBP project uses the One Plan Approach to amphibian sustainability [

35], where Cologne Zoo and private caregivers work with research and habitat protection in a holistic and inclusive international program [

35,

140,

141,

142,

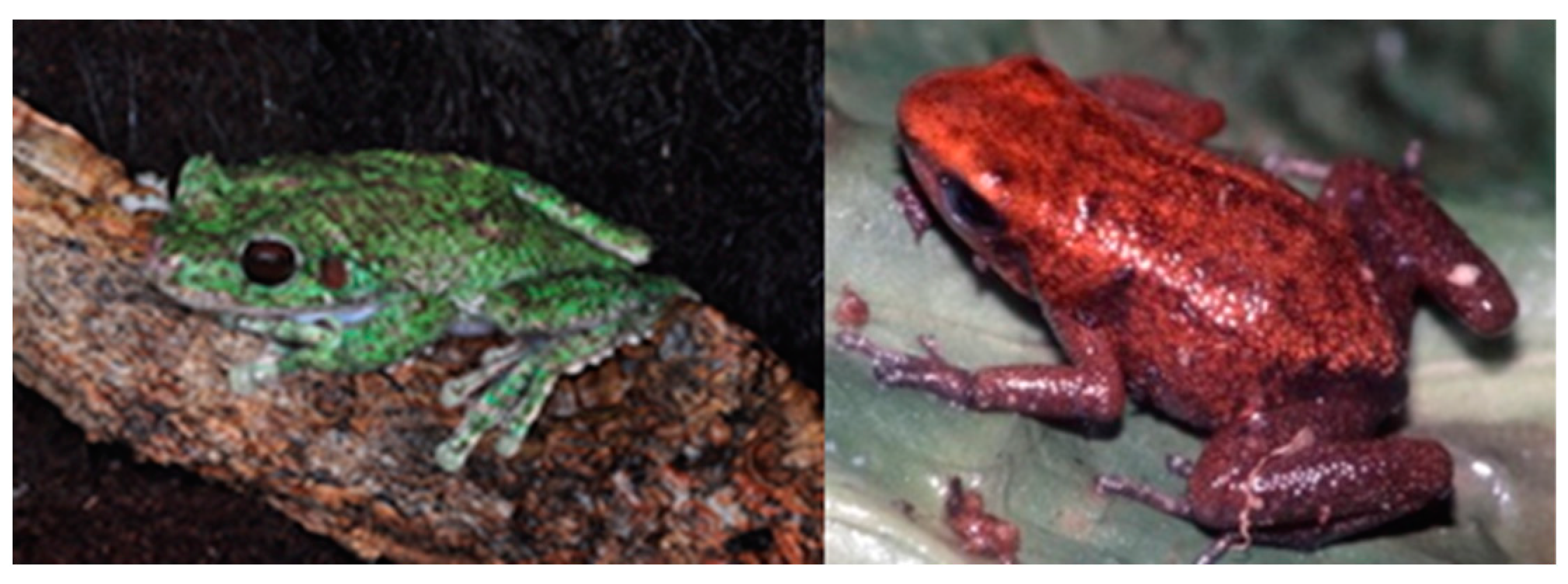

143]. A highly respected private keeper in Germany, Karl-Heinz Jungfer, shows the ability of individuals alone to contribute. Karl-Heinz found the CE San Martin Fringe-Limbed Treefrog,

Ecnomiohyla valancifer at a fair (

Figure 3, left), a species previously known only from a handful of museum specimens, and his CBP has bred many specimens and is likely a last hope for this species. Karl-Heinz also champions a CBP for the CE demonic poison frog,

Minyobates steyermarki (

Figure 3, right).

Several amphibian genera particularly appeal to private caregiver CBPs, including the very popular

Atelopus sp. [

144], with an IUCN Red Listing of 62 CE and 14 EN species [

2,

144], and an AArk listing for CBPs of 30 CE and 14 EN [

42], with 37 species not evaluated and several species possibly extinct in the wild.

Atelopus sp. have established captive care protocols and offer unique opportunities for developing and applying RBCs [

144].

Neurergus is a small but very popular salamander clade with private carers regularly breeding three VU species, but the CE

N.

microspilotus still needs to be included in private collections [

25]. Of other salamanders, the popular warty Asian newts include thirty

Tylototriton sp. including two CE and five EN, and eight

Paramesotriton sp., including one CE and three EN. Fully aquatic amphibians include the Axolotl and three other CE

Ambystoma sp., and of anurans, many highly endangered

Telmatobius sp. [

2].

7. Biobanking Facilities

Biobanking includes three categories: (1) “Research Biobanks”, (2) “Active Management Biobanks” for maintaining genetic diversity in CBPs or wild populations, and (3) “Perpetuity Biobanks” for species restoration [

21,

111,

135,

145]. Biobanks need ongoing financial support [

38,

135], with samples collected, processed, stored, and distributed within conventional guidelines and standards [

135,

146,

147,

148], and the International Society for Biological and Environmental Repositories [ISBER] promoting effective management [

148].

Examples of Perpetuity Biobanks include and the Chinese Academy of Science Kunming Cell Bank [

149] and Nature’s SAFE recently established in 2020 the UK [

150]. Nature’s SAFE was the first cryo-network partner of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria [EAZA] Biobank, one of Europe’s largest biobanks, collecting samples from 400 zoo and aquarium members in 48 countries. Four dedicated institutions provide qualified staff and funds for four hub biobanks that provide sample processing and facilitate sample transfer and backup [

151]. The Biodiversity Biobanks South Africa project provides coordination across existing South African biodiversity biobanks. It has biobanked South Africa’s exceptionally high species diversity and endemism for over 20 years [

152].

The establishment of amphibian collections in all categories of biobanks is gaining momentum [

Table 5]. These include active management through the National Genome Resource Bank program at Mississippi State University, supporting RCBs toward threatened species in the USA and its territories [

38]. Australia also has an active management biobank supported by universities and zoos, including sperm banking for species undergoing rapid decline [

134]. Smaller projects are underway in the Global South and other developing countries [

Table 5]. All these programs are supporting basic research to advance reproduction technologies. A direct link between the climate catastrophe and RBCs followed Australia’s unprecedented 2019/20 megafires [

134].

However, amphibians are poorly represented in Perpetuity Biobanks. For instance, the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance’s Frozen Zoo

® is one of the world’s largest biobanks and contains 10,000 samples [

154]. The biobank houses 12.0% of EN and 14.6% of CE Mammalia, and 2.3% of EN and 4.8% of CE Reptilia/Aves. Amphibia are represented by 0.3% of EN and 0.4% of CE species, with 24 species in total, most of which are LC (not tabulated) (

Table 6). The Chinese Academy of Science, Kunming Cell Bank, was established in 1986 and has now preserved 1455 cell lines from 298 animal species, including 17 amphibians [

149].

10. The Road Ahead

Intergenerational justice and laws based on protecting the Earth and its biodiversity as legal entities provide profound cultural foundations toward biospheric sustainability. These cultural initiatives toward ecological civilisation are supported by COP 15, COP 28, and other protocols to support and finance biospheric sustainability. However, until the plateau of anthropogenic destruction of Earth’s ecosystems is reached and potentially reversed, a significant amount of biodiversity will be lost in the wild. We have demonstrated the ability of RBCs to prevent cost-effectively and reliably some of the alarming loss of amphibian diversity not protected by COPs 15 and 28.

We live in a multipolar world with increasing assertion and technical prowess in the biodiversity-rich Global South and other developing countries. However, the past has been defined by colonialism and exploitation, resulting in massive environmental destruction and cultural subjugation. Amphibian RBCs present exciting opportunities for community engagement through broad international programs, extending from local custodianship to a global presence. Including institutional and private caregivers in amphibian RBCs complements these potentials for biospheric sustainability. However, the potential for empowerment across all geopolitical and biopolitical regions still needs to be realised. Similarly, to reach their full potential, amphibian RBCs must extend beyond the research emphases on gamete collection, storage, and in vitro fertilisation, to include species perpetuation solely in biobanks through further research and the establishment of RBC facilities globally.

We provided a triage for allocation of resources to RBCs over a range of species doomed to extinction in the wild, for those species where field projects potentially ensure their survival. These approaches should be in tandem to provide the most effective use of resources from increasingly funded biospheric sustainability initiatives. Then, as corals exemplify, a dynamic multidisciplinary approach will synergise support and resource availability for amphibian sustainability in the face of the inevitable modification and loss of habitats and ecosystems.

In this era of major geopolitical realignments and environmental and social challenges, we see an opportunity for innovative strategies involving amphibian RBCs to ensure biospheric sustainability. Our vision involves establishing a globally representative organisation dedicated to championing the establishment of amphibian RBCs in the neediest regions. By promoting inclusive and democratic management through representation from the regions in need, we aim to create a robust, globally representative organisation capable of effectively advocating for RBC project development and fundraising.

These organisational requirements include expertise and the ability to form non-partisan and extensive networks with global biopolitical and geopolitical entities. Bringing together diverse voices to support a shared vision would result in a synergised global initiative that attracts expert, dynamic, and motivated contributors, especially early-career professionals, ensuring the proactive sustainability of amphibians well into the 21st century. If extended to other taxa, this model could result in further significant contributions to biospheric sustainability and intergenerational justice.