“Do Your Homework as Your Heart Takes over When You Go Looking”: Factors Associated with Pre-Acquisition Information-Seeking among Prospective UK Dog Owners

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

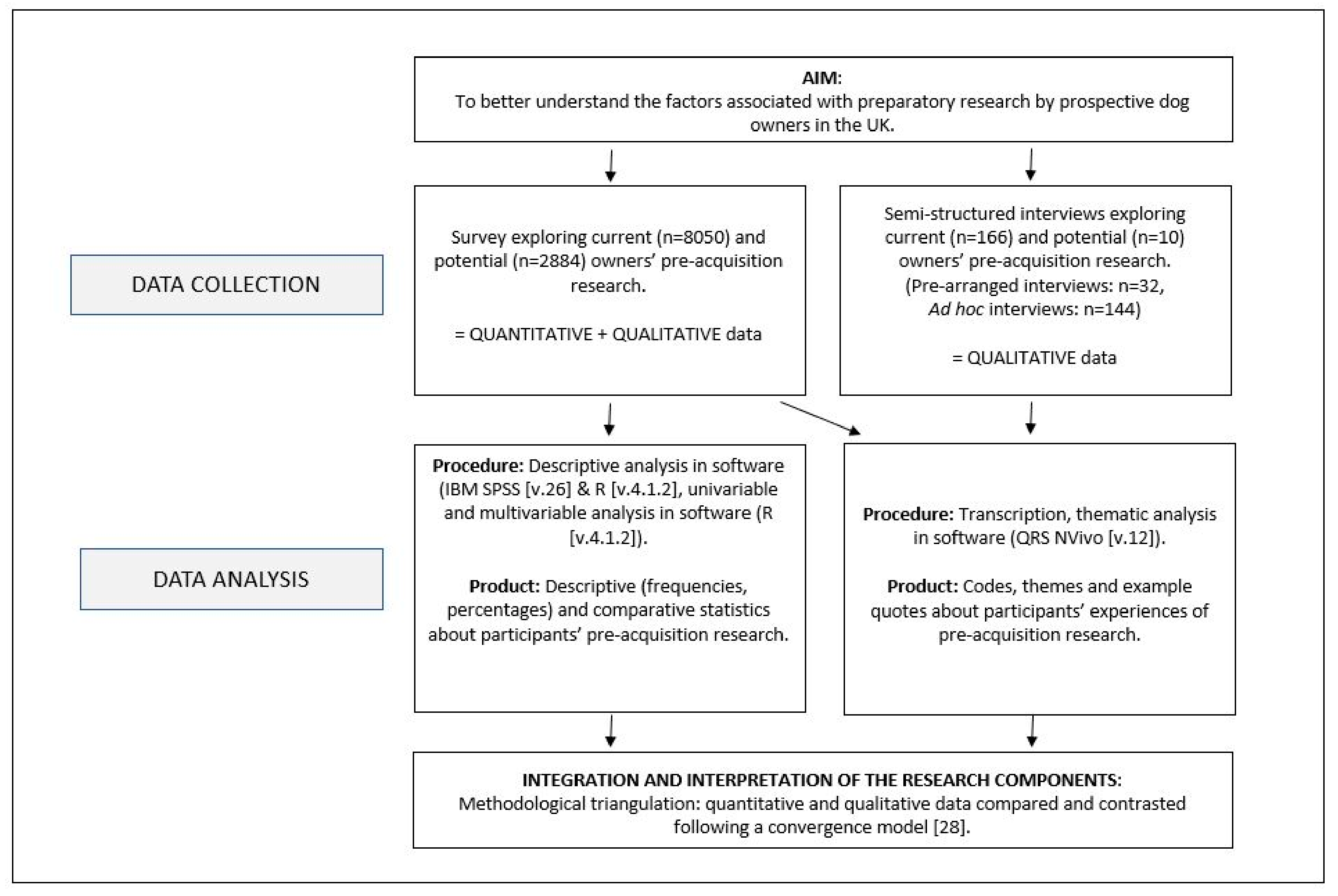

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Survey Design and Content

2.2.2. Survey: Participant Recruitment

2.2.3. Interviews

2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Quantitative Data Analysis

2.3.2. Qualitative Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Survey Results

3.1.1. Participant Demographics

3.1.2. Dog Demographics

3.2. Do Prospective Owners Look for Information or Advice before Acquiring a Dog?

3.3. What Factors Influence Whether Prospective Owners Undertake Research Prior to Acquiring a Dog?

| Undertook Research | Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis (n = 7279) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Yes | Total | % | 95% CI | Odds Ratio 1 | 2.50% | 97.50% | z Val. | p Val. | Odds Ratio | 2.50% | 97.50% | z Val. | p Val. 2 |

| Previous ownership (n = 8050) | ||||||||||||||

| Previously lived with a dog/dogs as an adult and as a child | 1588 | 3546 | 44.78% | 43.15%, 46.42% | Ref | <0.0001 | Ref | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Previously lived with a dog/dogs as an adult | 1236 | 2458 | 50.28% | 48.31%, 52.26% | 1.25 | 1.13 | 1.38 | 4.20 | <0.0001 | 1.22 | 1.09 | 1.36 | 3.39 | 0.0007 |

| Previously lived with a dog/dogs as a child | 850 | 1188 | 71.55% | 68.92%, 74.04% | 3.10 | 2.69 | 3.58 | 15.58 | <0.0001 | 2.53 | 2.16 | 2.96 | 11.60 | <0.0001 |

| First time lived with a dog | 707 | 858 | 82.40% | 79.71%, 84.81% | 5.77 | 4.79 | 6.97 | 18.30 | <0.0001 | 4.61 | 3.75 | 5.66 | 14.56 | <0.0001 |

| Age of owner (n = 7987) | ||||||||||||||

| 75 years or older | 65 | 196 | 33.16% | 26.94%, 40.03% | Ref | <0.0001 | Ref | <0.0001 | ||||||

| 65–74 years | 463 | 1126 | 41.12% | 38.28%, 44.02% | 1.41 | 1.02 | 1.94 | 2.09 | 0.0364 | 1.31 | 0.92 | 1.87 | 1.48 | 0.1388 |

| 55–64 years | 904 | 1821 | 49.64% | 47.35%, 51.94% | 1.99 | 1.46 | 2.71 | 4.32 | <0.0001 | 1.55 | 1.10 | 2.20 | 2.49 | 0.0128 |

| 45–54 years | 1036 | 1916 | 54.07% | 51.83%, 56.29% | 2.37 | 1.74 | 3.24 | 5.45 | <0.0001 | 1.59 | 1.12 | 2.25 | 2.60 | 0.0092 |

| 35–44 years | 731 | 1206 | 60.61% | 57.83%, 63.33% | 3.10 | 2.25 | 4.27 | 6.95 | <0.0001 | 1.76 | 1.23 | 2.52 | 3.08 | 0.0021 |

| 18–24 years | 311 | 474 | 65.61% | 61.22%, 69.75% | 3.85 | 2.70 | 5.47 | 7.49 | <0.0001 | 2.02 | 1.35 | 3.03 | 3.43 | 0.0006 |

| 25–34 years | 839 | 1248 | 67.23% | 64.57%, 69.78% | 4.13 | 3.00 | 5.69 | 8.69 | <0.0001 | 2.28 | 1.58 | 3.28 | 4.43 | <0.0001 |

| Work with dogs (n = 7850) | ||||||||||||||

| Currently work with dogs | 386 | 776 | 49.74% | 46.23%, 53.25% | Ref | <0.0001 | Ref | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Previously worked with dogs | 380 | 786 | 48.35% | 44.87%, 51.84% | 0.95 | 0.78 | 1.15 | -0.55 | 0.5810 | 1.23 | 0.99 | 1.53 | 1.83 | 0.0667 |

| Never worked with dogs | 3409 | 6116 | 55.74% | 54.49%, 56.98% | 1.27 | 1.10 | 1.48 | 3.18 | 0.0015 | 1.48 | 1.25 | 1.75 | 4.52 | <0.0001 |

| Highest level of education (n = 7373) | ||||||||||||||

| No formal qualifications | 107 | 321 | 33.33% | 28.40%, 38.66% | Ref | <0.0001 | Ref | <0.0001 | ||||||

| GCSE/National 5 or equivalent | 656 | 1384 | 47.40% | 44.78%, 50.03% | 1.80 | 1.40 | 2.33 | 4.53 | <0.0001 | 1.42 | 1.08 | 1.86 | 2.50 | 0.0123 |

| A level/Scottish Higher or equivalent | 525 | 965 | 54.40% | 51.25%, 57.52% | 2.39 | 1.83 | 3.11 | 6.45 | <0.0001 | 1.51 | 1.13 | 2.01 | 2.81 | 0.0049 |

| Foundation degree/Higher National Diploma (HND) or equivalent | 570 | 1085 | 52.53% | 49.56%, 55.49% | 2.21 | 1.71 | 2.87 | 5.97 | <0.0001 | 1.56 | 1.18 | 2.06 | 3.10 | 0.0019 |

| University degree (e.g., BA, BSc) or equivalent | 1362 | 2305 | 59.09% | 57.07%, 61.08% | 2.89 | 2.26 | 3.70 | 8.44 | <0.0001 | 1.83 | 1.40 | 2.38 | 4.44 | <0.0001 |

| Postgraduate degree (e.g., MA, MBA, MSc, PhD) or equivalent | 831 | 1313 | 63.29% | 60.65%, 65.86% | 3.45 | 2.66 | 4.46 | 9.41 | <0.0001 | 2.27 | 1.72 | 3.00 | 5.76 | <0.0001 |

| Source of dog (n = 8050) | ||||||||||||||

| Friends or family/community | 393 | 979 | 40.14% | 37.12%, 43.25% | Ref | <0.0001 | Ref | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Private/third party seller | 208 | 454 | 45.81% | 41.29%, 50.41% | 1.26 | 1.01 | 1.58 | 2.02 | 0.0431 | 1.17 | 0.91 | 1.50 | 1.20 | 0.2299 |

| Charity/rehoming centre | 1655 | 3427 | 48.29% | 46.62%, 49.97% | 1.39 | 1.21 | 1.61 | 4.50 | <0.0001 | 1.52 | 1.28 | 1.80 | 4.74 | <0.0001 |

| A dog breeder | 2125 | 3190 | 66.61% | 64.96%, 68.23% | 2.98 | 2.57 | 3.45 | 14.49 | <0.0001 | 2.38 | 1.99 | 2.83 | 9.61 | <0.0001 |

| Breed or type of dog (n = 7596) | ||||||||||||||

| Mix of breeds or types | 844 | 979 | 45.82% | 43.56%, 48.10% | Ref | <0.0001 | Ref | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Mix of two specific breeds | 1012 | 3190 | 56.60% | 54.29%, 58.88% | 1.54 | 1.35 | 1.76 | 6.48 | <0.0001 | 1.18 | 1.01 | 1.38 | 2.06 | 0.0395 |

| Specific breed | 2525 | 3427 | 57.13% | 55.66%, 58.58% | 1.58 | 1.41 | 1.76 | 8.15 | <0.0001 | 1.37 | 1.19 | 1.57 | 4.43 | <0.0001 |

| Year acquired | 1.05 | 1.04 | 1.07 | 8.53 | <0.0001 | 1.06 | 1.04 | 1.07 | 7.83 | <0.0001 | ||||

| Age of dog when acquired 3 (n = 8050) | ||||||||||||||

| Senior adult (7 to <12 years) | 195 | 465 | 41.94% | 37.53%, 46.47% | Ref | <0.0001 | Ref | 0.0004 | ||||||

| Juvenile (>6 months to <1 year) | 30 | 65 | 46.15% | 34.59%, 58.15% | 1.13 | 0.88 | 1.46 | 0.98 | 0.3295 | 1.11 | 0.84 | 1.47 | 0.72 | 0.4713 |

| Geriatric (12+ years) | 334 | 755 | 44.24% | 40.73%, 47.80% | 1.19 | 0.70 | 2.00 | 0.64 | 0.5196 | 1.21 | 0.67 | 2.18 | 0.64 | 0.5224 |

| Young adult (1 to <2 years) | 394 | 888 | 44.37% | 41.13%, 47.65% | 1.07 | 0.85 | 1.34 | 0.55 | 0.5818 | 1.23 | 0.95 | 1.58 | 1.58 | 0.1137 |

| Mature adult (2 to <7 years | 755 | 1496 | 50.47% | 47.94%, 53.00% | 1.38 | 1.12 | 1.70 | 3.04 | 0.0024 | 1.41 | 1.12 | 1.77 | 2.94 | 0.0033 |

| Puppy (0–6 months) | 2673 | 4381 | 61.01% | 59.56%, 62.45% | 2.17 | 1.78 | 2.63 | 7.81 | <0.0001 | 1.59 | 1.25 | 2.03 | 3.80 | 0.0001 |

| Undertook Research | Univariable Analysis | Multivariable Analysis (n = 2272) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Yes | Total | % | 95% CI | Odds Ratio 1 | 2.50% | 97.50% | z Val. | p Val. | Odds Ratio | 2.50% | 97.50% | z Val. | p Val. 2 |

| Previous ownership (n = 2861) | ||||||||||||||

| Previously lived with a dog/dogs as an adult and as a child | 1086 | 1403 | 77.41% | 75.14%, 79.52% | Ref | <0.0001 | Ref | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Previously lived with a dog/dogs as an adult | 689 | 880 | 78.30% | 75.45%, 80.90% | 0.72 | 0.50 | 1.02 | −1.83 | 0.0679 | 1.36 | 1.06 | 1.74 | 2.43 | 0.0151 |

| Previously lived with a dog/dogs as a child | 284 | 303 | 93.73% | 90.86%, 96.00% | 3.15 | 1.26 | 7.87 | 2.45 | 0.0141 | 3.56 | 2.02 | 6.27 | 4.39 | <0.0001 |

| Never lived with a dog | 269 | 275 | 97.82% | 95.21%, 99.11% | 5.09 | 1.59 | 16.28 | 2.74 | 0.0061 | 11.10 | 4.07 | 30.28 | 4.70 | <0.0001 |

| Age of owner (n = 2865) | ||||||||||||||

| 65–74 years | 274 | 374 | 73.26% | 68.55%, 77.50% | Ref | <0.0001 | Ref | <0.0001 | ||||||

| 55–64 years | 449 | 599 | 74.96% | 71.33%, 78.27% | 1.30 | 0.78 | 2.18 | 1.01 | 0.3120 | 1.05 | 0.74 | 1.49 | 0.26 | 0.7932 |

| 75 years or older | 60 | 88 | 68.18% | 57.84%, 77.01% | 0.71 | 0.32 | 1.56 | −0.85 | 0.3960 | 1.09 | 0.59 | 1.99 | 0.27 | 0.7870 |

| 45–54 years | 457 | 573 | 79.76% | 76.27%, 82.85% | 1.17 | 0.70 | 1.95 | 0.61 | 0.5406 | 1.45 | 1.00 | 2.10 | 1.95 | 0.0515 |

| 35–44 years | 388 | 453 | 85.65% | 82.11%, 88.59% | 3.58 | 1.72 | 7.48 | 3.40 | 0.0007 | 1.60 | 1.07 | 2.40 | 2.29 | 0.0218 |

| 25–34 years | 507 | 562 | 90.21% | 87.46%, 92.42% | 2.76 | 1.47 | 5.18 | 3.17 | 0.0015 | 2.95 | 1.90 | 4.57 | 4.83 | <0.0001 |

| 18–24 years | 198 | 216 | 91.67% | 87.14%, 94.73% | 5.75 | 1.73 | 19.12 | 2.85 | 0.0044 | 3.34 | 1.76 | 6.36 | 3.68 | 0.0002 |

| Work with dogs (n = 2716) | ||||||||||||||

| Currently work with dogs | 275 | 361 | 76.20% | 71.5%, 80.3% | Ref | 0.0113 | Ref | 0.0124 | ||||||

| Previously worked with dogs | 133 | 155 | 85.80% | 79.4%, 90.5% | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.93 | −2.03 | 0.0428 | 1.04 | 0.59 | 1.83 | 0.13 | 0.8948 |

| Never worked with dogs | 1813 | 2200 | 82.40% | 80.8%, 83.9% | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.92 | −2.04 | 0.0413 | 1.58 | 0.94 | 2.64 | 1.74 | 0.0817 |

“Whether I would have the time and resources needed to give a dog a good home.”(Current owner, survey ID 3136)

“Everything I may need to know to look after him/her to the best of my ability. And make sure she has everything to fit her needs.”(Potential owner, survey ID P3287)

“Do your homework as your heart takes over when you go looking.”(Current owner, survey ID 1274)

“As she’s our first dog, we did a lot of research into different breeds and their personalities.”(Current owner, survey ID 1549)

“We haven’t had a puppy between us before […] so we had a lot of studying to do about puppies.”(Current owner, survey ID 1828)

“I have previously owned 3 dogs and have researched each one. Over the last month, I’ve been giving myself a refresher course.”(Potential owner, survey ID 2841)

“Quite knowledgeable on dogs in general, so was more specific to specific dog and situation and breed that I’ve never had before.”(Current owner, survey ID 1900)

“As I had not owned a dog for 20 years.”(Current owner, survey ID 8340)

“We did have experience of this [rehoming a Greyhound], having rehomed two retired racers, but the more advice the better!”(Current owner, survey ID 8292)

“I didn’t [do any research] because I’m one of these people that thinks they know everything; do you know what I mean? Because I had had animals and had dogs and done dog training and dog trials, I had a very high opinion of myself. What, you know dog temperaments and how to train them and all that kind of thing, so no I didn’t get any advice whatsoever.”(Current owner, interview ID B1RM1201)

“We didn’t [do any research] as we’d had that breed before.”(Current owner, survey ID 2279)

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

4.2. Future Work

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- PFMA. UK Pet Population. Available online: https://www.ukpetfood.org/information-centre/statistics/uk-pet-population.html (accessed on 31 May 2022).

- Packer, R.M.A.; Brand, C.L.; Belshaw, Z.; Pegram, C.L.; Stevens, K.B.; O’neill, D.G. Pandemic puppies: Characterising motivations and behaviours of UK owners who purchased puppies during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Animals 2021, 11, 2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennel Club. Breed Registration Statistics. 2020. Available online: https://www.thekennelclub.org.uk/media-centre/breed-registration-statistics/ (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Packer, R.M.A.; Hendricks, A.; Tivers, M.S.; Burn, C.C. Impact of facial conformation on canine health: Brachycephalic obstructive airway syndrome. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honey, L. Future health and welfare crises predicted for the brachycephalic dog population. Vet. Rec. 2017, 181, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, D.G.; Jackson, C.; Guy, J.H.; Church, D.B.; McGreevy, P.D.; Thomson, P.C.; Brodbelt, D.C. Epidemiological associations between brachycephaly and upper respiratory tract disorders in dogs attending veterinary practices in England. Canine Genet. Epidemiol. 2015, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, D.G.; Baral, L.; Church, D.B.; Brodbelt, D.C.; Packer, R.M.A. Demography and disorders of the French Bulldog population under primary veterinary care in the UK in 2013. Canine Genet. Epidemiol. 2018, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asher, L.; Diesel, G.; Summers, J.F.; McGreevy, P.D.; Collins, L.M. Inherited defects in pedigree dogs. Part 1: Disorders related to breed standards. Vet. J. 2009, 182, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogs Trust. Puppy Smuggling: Puppies Still Paying as Government Delays. 2020. Available online: https://www.dogstrust.org.uk/downloads/2020%20Puppy%20smuggling%20report.pdf (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Wyatt, T.; Maher, J.; Biddle, P. Scoping Research on the Sourcing of Pet Dogs From Illegal Importation and Puppy Farms 2016–2017, Scottish Government. 2017. Available online: https://www.gov.scot/publications/scoping-research-sourcing-pet-dogs-illegal-importation-puppy-farms-2016/documents/ (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Wauthier, L.M.; Williams, J.M. Using the Mini C-BARQ to Investigate the Effects of Puppy Farming on Dog Behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 206, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavisky, J.; Brennan, M.L.; Downes, M.; Dean, R. Demographics and economic burden of un-owned cats and dogs in the UK: Results of a 2010 census. BMC Vet. Res. 2012, 8, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.C.A.; Gruffydd-Jones, T.; Murray, J.K. Number of cats and dogs in UK welfare organisations. Vet. Rec. 2012, 170, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.B.H.; Sandøe, P.; Nielsen, S.S. Owner-related reasons matter more than behavioural problems—A study of why owners relinquished dogs and cats to a Danish animal shelter from 1996 to 2017. Animals 2020, 10, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, K.; Coe, J.; Niel, L.; Dewey, C.; Sargeant, J.M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the proportion of dogs surrendered for dog-related and owner-related reasons. Prev. Vet. Med. 2015, 118, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagan, B.H.; Gordon, E.; Protopopova, A. Reasons for Guardian-Relinquishment of Dogs to Shelters: Animal and Regional Predictors in British Columbia, Canada. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diesel, G.; Brodbelt, D.; Pfeiffer, D.U. Characteristics of relinquished dogs and their owners at 14 rehoming centers in the united kingdom. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2010, 13, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogs Trust. Getting or Buying a Dog. Available online: https://www.dogstrust.org.uk/help-advice/getting-or-buying-a-dog/ (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Kennel Club. When Buying a Dog. Available online: https://www.thekennelclub.org.uk/getting-a-dog/buying-a-dog/ (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Buying a Puppy. Available online: https://www.rspca.org.uk/adviceandwelfare/pets/dogs/puppy (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals (PDSA). Getting a Dog. Available online: https://www.pdsa.org.uk/pet-help-and-advice/looking-after-your-pet/puppies-dogs/getting-a-dog (accessed on 13 May 2022).

- Upjohn, M. Going beyond “educating”: Using behaviour change frameworks to help pet owners make evidence-based welfare decisions. Vet Rec. 2022, 190, 412–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, R.M.A.; Murphy, D.; Farnworth, M.J. Purchasing popular purebreds: Investigating the influence of breed-Type on the pre-purchase motivations and behaviour of dog owners. Anim. Welf. 2017, 26, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhl, C.A.; Dean, R.; Quarmby, C.; Lea, R.G. Information sourcing by dog owners in the UK: Resource selection and perceptions of knowledge. Vet. Rec. 2021, 190, e1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhl, C. An Investigation of Pedigree Dog Breeding and Ownership in the UK: Experiences and Opinions of Veterinary Surgeons, Pedigree Dog Breeders and Dog Owners. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Burnett, E.; Brand, C.L.; O’Neill, D.G.; Pegram, C.L.; Belshaw, Z.; Stevens, K.B.; Packer, R.M.A. How much is that doodle in the window? Exploring motivations and behaviours of UK owners acquiring designer crossbreed dogs (2019–2020). Canine Med. Genet. 2022, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, K.E.; Mead, R.; Casey, R.A.; Upjohn, M.M.; Christley, R.M. Why Do People Want Dogs? A Mixed-Methods Study of Motivations for Dog Acquisition in the United Kingdom. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 877950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.L.P. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research; SAGE Publications, Ltd.: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, K.E.; Mead, R.; Casey, R.A.; Upjohn, M.M.; Christley, R.M. “Don’t Bring Me a Dog…I’ll Just Keep It”: Understanding Unplanned Dog Acquisitions Amongst a Sample of Dog Owners Attending Canine Health and Welfare Community Events in the United Kingdom. Animals 2021, 11, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, K.E. Acquiring a pet dog: A review of factors affecting the decision-making of prospective dog owners. Animals 2019, 9, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, H. Women Dominate Research on Human-Animal Bond. Am. Psychol. J. 2021. Available online: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1010&context=sc_herzog_compiss (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Dogs Trust. Stray Dogs Survey Report 2017–18. 2018. Available online: https://www.dogstrust.org.uk/help-advice/research/research-papers/stray-dogs-survey (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malterud, K.; Siersma, V.D.; Guassora, A.D. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual. Health Res. 2016, 26, 1753–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennink, M.M.; Kaiser, B.N.; Marconi, V.C. Code Saturation Versus Meaning Saturation: How Many Interviews Are Enough? Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, N.D. How Old Is My Dog? Identification of Rational Age Groupings in Pet Dogs Based Upon Normative Age-Linked Processes. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 643085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals (PDSA). The PDSA Animal Wellbeing (PAW) Report 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.pdsa.org.uk/media/10540/pdsa-paw-report-2020.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2022).

- Rault, J.L.; Waiblinger, S.; Boivin, X.; Hemsworth, P. The Power of a Positive Human–Animal Relationship for Animal Welfare. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 590867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friemel, T.N. The digital divide has grown old: Determinants of a digital divide among seniors. New Media Soc. 2016, 18, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofcom. Adults’ Media Use & Attitudes: Report 2020. 2020. Available online: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0031/196375/adults-media-use-and-attitudes-2020-report.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2022).

- Office for National Statistics. Internet Users, UK. 2021. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/businessindustryandtrade/itandinternetindustry/bulletins/internetusers/2020 (accessed on 23 June 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mead, R.; Holland, K.E.; Casey, R.A.; Upjohn, M.M.; Christley, R.M. “Do Your Homework as Your Heart Takes over When You Go Looking”: Factors Associated with Pre-Acquisition Information-Seeking among Prospective UK Dog Owners. Animals 2023, 13, 1015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13061015

Mead R, Holland KE, Casey RA, Upjohn MM, Christley RM. “Do Your Homework as Your Heart Takes over When You Go Looking”: Factors Associated with Pre-Acquisition Information-Seeking among Prospective UK Dog Owners. Animals. 2023; 13(6):1015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13061015

Chicago/Turabian StyleMead, Rebecca, Katrina E. Holland, Rachel A. Casey, Melissa M. Upjohn, and Robert M. Christley. 2023. "“Do Your Homework as Your Heart Takes over When You Go Looking”: Factors Associated with Pre-Acquisition Information-Seeking among Prospective UK Dog Owners" Animals 13, no. 6: 1015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13061015

APA StyleMead, R., Holland, K. E., Casey, R. A., Upjohn, M. M., & Christley, R. M. (2023). “Do Your Homework as Your Heart Takes over When You Go Looking”: Factors Associated with Pre-Acquisition Information-Seeking among Prospective UK Dog Owners. Animals, 13(6), 1015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13061015