GHG Emissions from Dairy Small Ruminants in Castilla-La Mancha (Spain), Using the ManleCO2 Simulation Model

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Farms and Questionnaires

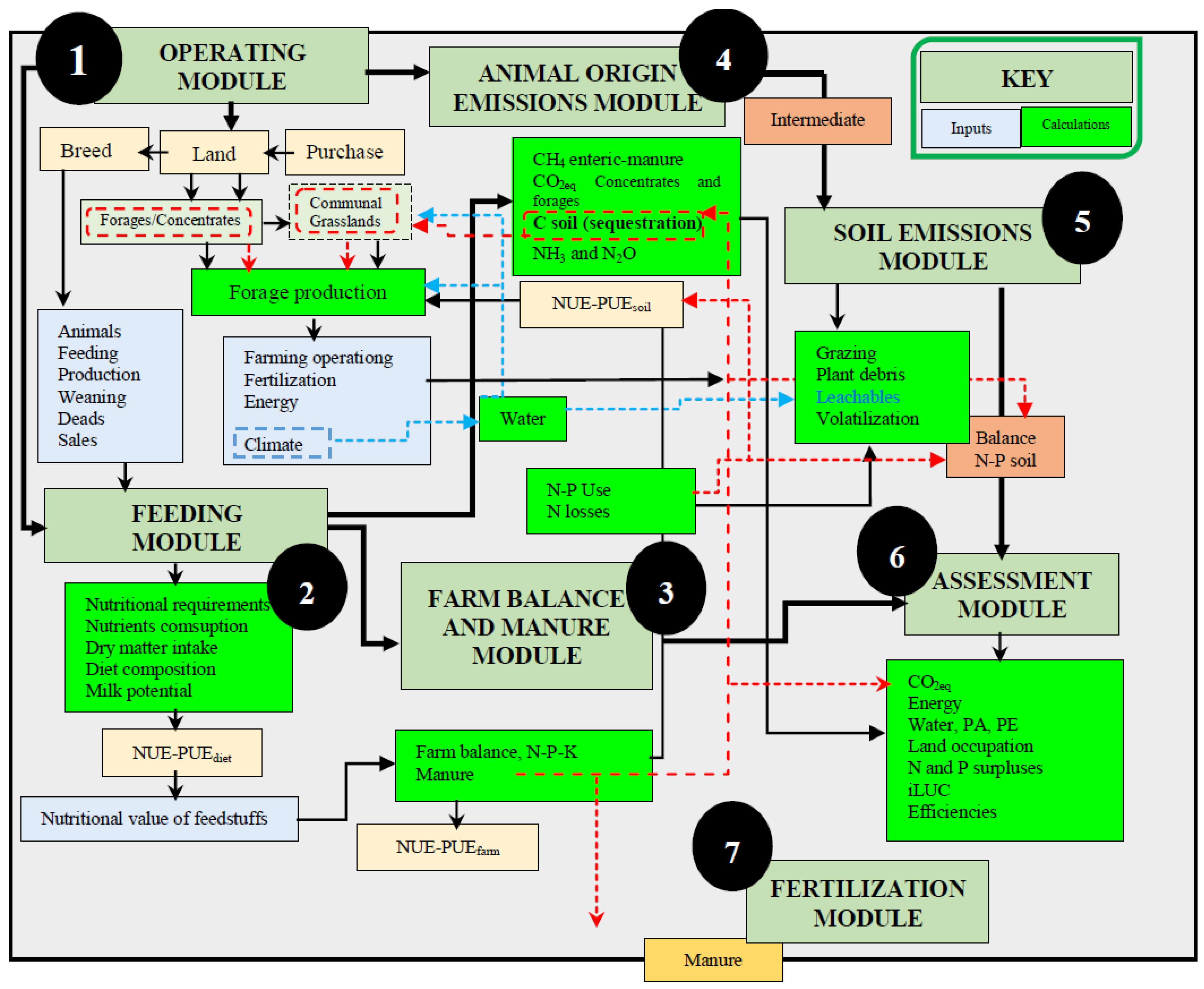

2.2. Simulation Model Description

- The farm’s forage potential and its intended use (hay, silage, or grazing).

- Input balance and outputs of nitrogen (N), phosphorous (P), and potassium (K), as well as potential losses in the soil–plant–animal system.

- Animal nutritional requirements; potential pasture consumption; N and P efficiencies; the excretion of N, P, K; and manure production.

- GHG assessment and potential carbon storage by the soil.

- Assessment of the farm’s environmental indicators, such as eutrophication and acidification potential, the whole N footprint, reactive N footprint, energy footprint, water footprint, and land use.

2.3. Criteria and Steps for Modeling

- (i)

- Selected independent variables should be either easily measurable or information about them should be readily available. An animal model was designed using the number of sheep as an independent variable. Regarding the calculation of manure and urine volumes, as well as the daily excretion of N in terms of feces and urine, the considered independent variables were: supplementation (volume of forage or off-farm concentrates), volume of daily ingestion of the diet or forage, or their chemical composition (dry matter (DM); nitrogen (N); neutral detergent fiber (NDF); acid detergent fiber (ADF); organic matter digestibility (OMD); ethereal extract (EE) and starch), DM ingestion (g/kg of live weight0.75), feeding level, the percentage of forage and concentrates in the diet, and the in vivo or in vitro digestibility of DM, ODM, NDF and N. Regarding forage production, the considered independent variables were the sowing rate (kg of seeds/ha); sprouting time (days); the number of heat units (expressed in growing degree-days [GDD], according to [Equation (1)] and considering that base temperature equals to 4 °C) [28]; rainfall (mm per month); the number of days from seed to harvest; sprouting time (days); basal dressing (kg of N-P-K per ha); side dressing (kg of N per ha); seeds (kg per ha); sprout length (cm); total stubble and straw production (kg per ha); grain/straw ratio (%); and harvested straw (kg per ha).

- (ii)

- The variables included in the models should be significant and highly correlated.

- (iii)

- The model should fulfill all the assumptions of multiple regression analysis.

- (iv)

- The model should have a high determination coefficient and a low standard error.

- (v)

- The model should have low multicollinearity.

- (i)

- Determination coefficient.

- (ii)

- Concordance index “d”, as a standardized measure of the degree of error of the model prediction (considering that it can vary from 0 to 1, it acts as a dimensionless statistical index). A value equal to 1 indicates a perfect clustering between the observed and the simulated values; conversely, a value equal to 0 indicates that there is no clustering [30].

- (iii)

- Root mean square error (RMSE), acting as a measure of the differences between the observations and the predictions [31].

- (iv)

- The mean bias error (MBE) shows the systematic deviation [31]. When the MBE has a negative value, this indicates the model’s underestimation; conversely, a positive value indicates an overestimation.

- (v)

- Model efficiency (EF), according to Nash and Sutcliffe [31], can vary from −1 to 1. When the EF value equals 1, this indicates a perfect coincidence between the simulated and the observed values; conversely, EF values of lower than 0 show that the average of the observed values would be a better predictor than the simulated values.

2.4. Modular Components of ManleCO2

2.4.1. Operating Module (MExCO2)

Animals

Land, Purpose, and Production (Only Considering the Area Used for Feeding Animals)

Energy

2.4.2. Feeding Module (MAlmCO2)

Feedstuffs

Nutritional Requirements

Nitrogen Use Efficiency (NUE) and Phosphorous Use Efficiency (PUE) in Animal Diets

2.4.3. Farm Balance and Manure Module (MEstNuCO2)

N and P Balance at Farm Level

Manure Production

2.4.4. Animal Origin Emissions Module (MEoaCO2)

2.4.5. Soil Emissions Module (MEsuCO2)

Animal Emissions, Soil Emissions, and Intermediate Calculations

2.4.6. Assessment Module (MVaCO2)

Carbon Footprint in Milk and Meat

Total Water Footprint (WFt)

Total Energy Footprint (EFt)

Acidification Potential (Ap) and Eutrophication Potential (Ep)

Total Nitrogen Footprint (NFt) and Reactive Nitrogen Footprint (NFr)

Land Use (Land UseOff, Land UseOn, and Land UseTotal)

2.4.7. Fertilization Module (MFt)

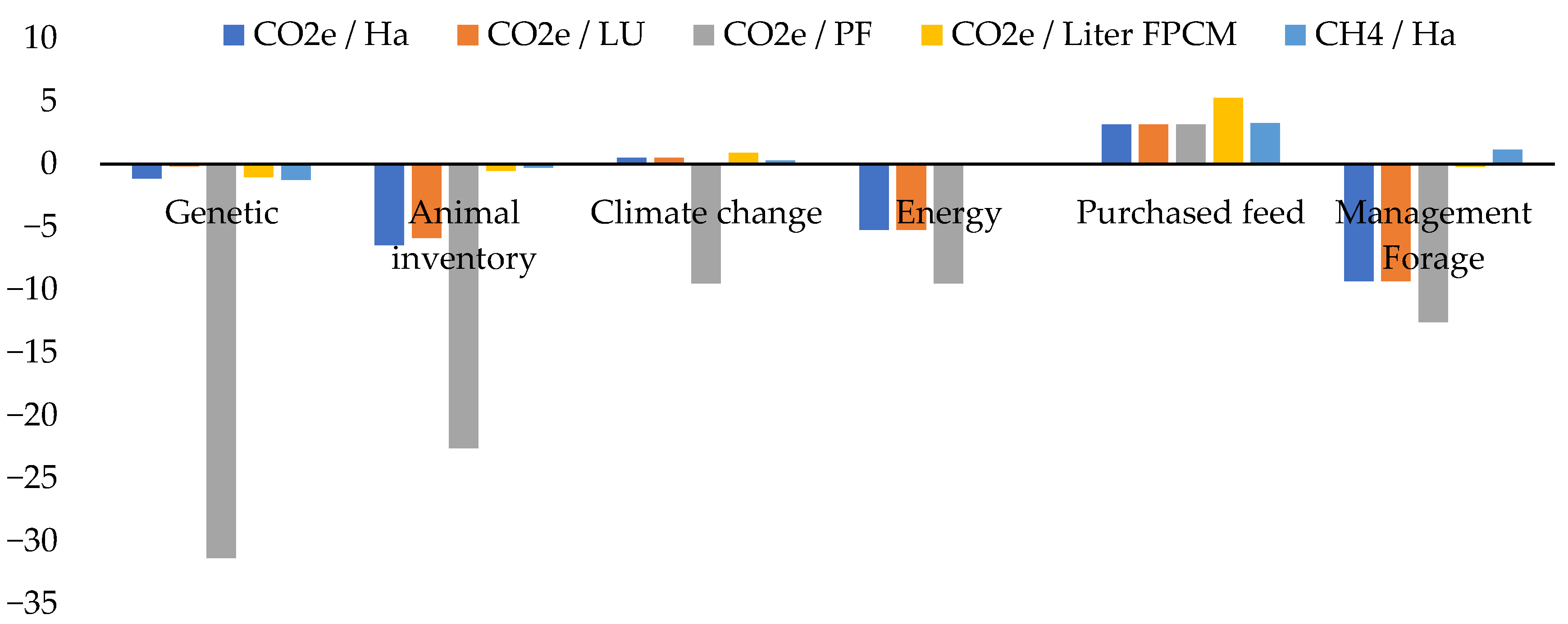

2.5. Simulated Scenarios

3. Results

3.1. Farms

3.2. Development of an Animal Model, Excreta Production Model, and Forage Production Model

3.3. Potential Mitigation in Different Scenarios

4. Discussion

4.1. Excreta Production Model

4.2. Forage Production Model

4.3. Mitigation Strategies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Statistical Yearbook; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2016; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Agricultura y Pesca, y Alimentación (MAPA). Resultados técnico-económicos del Ganado Ovino de leche en 2016, Subdirección General de Análisis, Prospectiva y Coordinación. Subsecretaría. 2016. Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/ministerio/servicios/analisis-y-prospectiva/ganadoovinodeleche_tcm30-520800.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- Ministerio de Agricultura y Pesca, y Alimentación [MAPA]. Indicadores cuatrimestrales situación sector ovino leche España. Subdirección General de Producciones Ganaderas y Cinegéticas, Dirección General de Producciones y Mercados Agrarios. 2020. Available online: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/ganaderia/estadisticas/ovinodeleche_indicadorsemestral_junio2021_rev_tcm30-428244.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- Montoro, V.; Vicente, J.; Rincón, E.; Pérez-Guzmán, M.D.; Gallego, R.; Rodríguez, J.M.; Arias, R.; Garde, J.J. Actualidad de la producción de ovino lechero en la Comarca Montes Norte de Ciudad Real: I. Estructura de las explotaciones. In Proceedings of the XXXII Jornadas Científicas y XI Jornadas Internacionales de Ovinotecnia y Caprinotecnia, Mallorca, Spain, 19–21 September 2007; p. 134. [Google Scholar]

- Toro-Mújica, P.; García, A.; Gómez-Castro, A.; Perea, J.; Rodríguez-Estévez, V.; Angón, E.; Barba, C. Organic dairy sheep farms in south-central Spain: Typologies according to livestock management and economic variables. Small Rum. Res. 2012, 104, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, M.; De Boer, I.J.M. Comparing environmental impacts for livestock products: A review of life cycle assessments. Livest. Sci. 2010, 128, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, P.J.; Steinfeld, H.; Henderson, B.; Mottet, A.; Opio, C.; Dijkman, J.; Falcucci, A.; Tempio, G. Tackling Climate Change Through Livestock: A Global Assessment of Emissions and Mitigation Opportunities; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Heilig, G. The Greenhouse Gas Methane (CH4): Sources and Sinks, the Impact of Population Growth, Possible Interventions. Popul. Environ. 1994, 16, 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hristov, A.N.; Oh, J.; Lee, C.; Meinen, R.; Montes, F.; Ott, T.; Firkins, J.; Rotz, A.; Dell, C.; Adesogan, A. Mitigation of Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Livestock Production: A Review of Technical Options for Non-CO2 Emissions; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.; Martino, D.; Cai, Z.; Gwary, D.; Janzen, H.; Kumar, P.; McCarl, B.; Ogle, S.; O’Mara, F.; Rice, C. Greenhouse gas mitigation in agriculture. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 789–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fraser, M.D.; Fleming, H.R.; Theobald, V.J.; Moorby, J.M. Effect of breed and pasture type on Methane emissions from weaned lambs offered fresh forage. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 153, 1128–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, Y.G.; Aubry, A.; O’Connell, N.E.; Annett, R.; Yan, T. Effects of breed, sex and concentrate supplementation on digestibility, enteric Methane emissions, and nitrogen utilization efficiency in growing lambs offered fresh grass. J. Anim. Sci. 2015, 93, 5764–5773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjo, V.S.; Sejian, V.; Bagath, M.; Ratnakaran, A.P.; Lees, A.M.; Al-Hosni, Y.A.S.; Sullivan, M.; Bhatta, R.; Gaughan, J.B. Modelización de emisiones de gases de efecto invernadero procedentes del ganado. Front. Environ. Sci. 2016, 4. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2016.00027/full (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- Lesschen, J.P.; van den Berg, M.; Westhoekb, H.J.; Witzkec, H.P.; Oenema, O. Greenhouse gas emission profiles of European livestock sectors. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2011, 166, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kram, T.; Stehfest, E. The IMAGE model: History, current status and prospects. In Integrated Modelling of Global Environmental Change; Bouwman, A.F., Kram, T., Goldewijk, K.K., Eds.; Netherlands Environmental Agency: Bilthoven, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Olesen, J.E.; Schelde, K.; Weiske, A.; Weisbjerg, M.R.; Asman, W.A.H.; Djurhuus, J. Modelling greenhouse gas emissions from European conventional and organic dairy farms. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2006, 112, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schils, R.L.M.; De Haan, M.H.A.; Hemmer, J.G.A.; Van den Pol-van Dasselaar, A.; De Boer, J.A.; Evers, A.G.; Holshof, G.; Van Middelkoop, J.C. DairyWise, a whole-farm dairy model. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 5334–5346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Prado, A.; Misselbrook, T.; Chadwick, D.; Hopkins, A.; Dewhurst, R.J.; Davison, P. SIMSDAIRY: A modelling framework to identify sustainable dairy farms in the UK. Framework description and test for organic systems and N fertilizer optimization. Sci. Total Environ. 2011, 409, 3993–4009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saletes, S.; Fiorelli, J.; Vuichard, N.; Cambou, J.; Olesen, J.E.; Hacala, S.; Sutton, M.; Fuhrer, J.; Soussana, J.F. Greenhouse gas balance of cattle breeding farms and assessment of mitigation options. In Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Agriculture. Mitigation Options and Strategies; Kaltschmitt, M., Weiske, A., Eds.; Institute for Energy and Environment: Leipzig, Germany, 2004; pp. 203–208. [Google Scholar]

- Chianese, D.S.; Rotz, C.A.; Richard, T.L. Whole-farm gas emissions: A review with application to a Pennsylvania dairy farm. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2009, 25, 431–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchings, N.J.; Kristensen, I.B. Measures to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions from dairy farming and their effect on nitrogen flow. In Abstracts 19th N Workshop, Proceedings of Efficient Use of Different Sources of Nitrogen in Agriculture–From Theory to Practice, Skara, Sweden, 27 June–29 June 2016; Aarhus University: Tjele, Denmark, 2016; pp. 179–181. [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo, G.; Salcedo-Rodríguez, D. Valoración holística de la sostenibilidad en los sistemas lecheros de la España húmeda. ITEA-Inf. Técnica Económica Agrar. 2021, 20, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, K.; Verburg, P.H.; Elbersen, B.; Stehfest, E.; Woltjer, G.B. Multi-scale scenarios of spatial-temporal dynamics in the European livestock sector. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2011, 140, 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.J.; Eckard, R.J.; Cullen, B.R. The effect of future climate scenarios on the balance between productivity and greenhouse gas emissions from sheep grazing systems. Livest. Sci. 2012, 147, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohan, A.; Shalloo, L.; Malcolm, B.; Ho, C.K.M.; Creighton, P.; Boland, T.M.; McHugh, N. Description and validation of the Teagasc Lamb Production Model. Agric. Syst. 2016, 148, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulina, G.; Macciotta, N.; Nudda, A. Milk composition and feeding in the Italian dairy sheep. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 4, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). CROPWAT 8.0 Model; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McMaster, G.; Wilhelm, W. Growing degree-days: One equation, two interpretations. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1987, 87, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belsley, D. Conditioning Diagnostics: Collinearity and Weak Data in Regression; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Willmott, C.J. Some comments on the evaluation of model performance. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1982, 63, 1309–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nash, J.E.; Sutcliffe, J.V. River flow forecasting through conceptual models part I—A discussion of principles. J. Hydrol. 1970, 10, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Agricultura y Pesca, y Alimentación (MAPA). Real Decreto 1131/2010, de 10 de septiembre, por el que se establecen los criterios para el establecimiento de las zonas remotas a efectos de eliminación de ciertos subproductos animales no destinados a consumo humano generados en las explotaciones ganaderas. (BOE 2-10-2010). Available online: https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2010-15123 (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- Regadas, J.G.; Tedeschi, L.O.; Rodrigues, M.T.; Brito, L.F.; Oliveira, T.S. Comparison of growth curves of two genotypes of dairy goats using nonlinear mixed models. J. Agric. Sci. 2014, 152, 8209–8842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vega, C. La relación paja-grano en los cereals. (Una aproximación en condiciones de secano semiárido, en Aragón). Inf. Técnicas Dep. Agric. Medio Ambiente 2000, 91, 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop Evapotranspiration Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements-FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper 56; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1998; Volume 300, p. 6541. [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo, G. Emisiones en la producción de forrajes de las explotaciones lecheras. ITEA Inf. Técnico Económica Agrar. 2020, 11, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cela, S.; Santiveri, F.; Lloveras, J. Short communication. Nitrogen content of residual alfalfa taproots under irrigation. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2013, 11, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petersen, B.M.; Knudsen, M.T.; Hermansen, J.E.; Halberg, N. An approach to include soil carbon changes in life cycle assessments. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 52, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirinda, N.; Olesen, J.E.; Porter, J.R. Root carbon input in organic and inorganic fertilizer-based systems. Plant Soil 2012, 359, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero, A.; Gonzalez-Arias, A.; del Hierro, O.; Pinto, M.; Gartzia-Bengoetxea, N. Nitrogen dynamics in soil amended with manures composted in dynamic and static systems. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 180, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A. Análisis de la Rentabilidad en las Explotaciones de Ovino de Leche en Castilla y León. Ph.D. Thesis, Facultad de Veterinaria de León, León, Spania, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bodas, R.; Tabernero de Paz, M.J.; Bartolomé, D.J.; Posado, R.; García, J.J.; Olmedo, S.; Rodríguez, L. Consumo eléctrico en granjas de ganado ovino lechero de Castilla y León. Arch. Zootec. 2013, 62, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- FEDNA. Tablas de Composición y Valor Nutritivo de Alimentos Para la Fabricación de Piensos Compuestos, 4th ed.; de Blas, C., Mateos, G.G., García-Rebollar, P., Eds.; Fundación Española para el Desarrollo de la Nutrición Animal: Madrid, Spain, 2010; p. 604. [Google Scholar]

- Alderman, G.; Cottrill, B.R. Energy and Protein Requirements of Ruminants: An Advisory Manual Prepared by the AFRC Technical Committee on Responses to Nutrients. 1993. Available online: https://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=GB9406276 (accessed on 14 March 2022).

- Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. UK Tables of Nutritive Value and Chemical Composition of Feeding Stuffs; Rowett Research Services: Aberdeen, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (NRC). Nutrient Requirements for Dairy Cattle, 7th rev. ed.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Vermorel, M.; Coulon, J.B.; Journet, M. Révision du systéme des unités fourragères (UF). Bull. Tech. Cent. Rech. Zootech. Vétérinaires Theix 1987, 70, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council (NRC). Nutrient Requirements of Sheep, 6th ed.; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi, L.O.; Molle, G.; Menendez, H.M.; Cannas, A.; Fonseca, M.A. The assessment of supplementation requirements of grazing ruminants using nutrition models. Transl. Anim. Sci. 2019, 3, 812–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pulina, G.; Bettati, T.; Serra, F.A.; Cannas, A. Razi-O: Development and validation of a software for dairy sheep feeding. In Proceedings of the XII National Meeting of the Societa Italiana di Patologia e d’Allevamento Degli Ovini e dei Caprini, Varese, Italy; 1996; pp. 11–14. [Google Scholar]

- Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA). Alimentation des Bovins, Ovins et Caprins: Besoins des Animaux—Valeurs des Aliments—Tables Inra; Editions Quae: Versailles, France, 2007; p. 310. [Google Scholar]

- Macoon, B.; Sollenberger, L.E.; Moore, J.E.; Staples, C.R.; Fike, J.H.; Portier, K.M. Comparison of three techniques for estimating the forage intake of lactating dairy cows on pasture. J. Anim. Sci. 2003, 81, 2357–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freer, M. Nutrient Requirements of Domestical Ruminants; CSIRO Publishing: Melbourne, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, M.P.; Caja, G.; Torres, A.; Gallego, L. ITEA: Producción Animal. Inf. Técnica Económica Agrar. 1991, 11, 277–279. [Google Scholar]

- Bocquier, F.; Barillet, F.; Guillouet, P. Prediction of gross energy content of ewe’s milk from different chemical analysis: Proposal of an energy corrected milk for dairy ewes. In Energy Metabolism of Farm Animals; EAAP: Zurich, Switzerland, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera, J.F.; Prieto, C.; Fonollá, J. Protein and energy metabolism of lactating Granadina goats. Brit. J. Nutr. 1990, 63, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cannas, A.; Tedeschi, L.O.; Fox, D.G.; Pell, A.N.; van Soest, P.J. A mechanistic model for predicting the nutrient requirements and feed biological values for sheep. J. Anim. Sci. 2004, 82, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA). Alimentación de los Rumiantes; INRA: Madrid, España, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Brentrup, F.; Küsters, J.; Lammel, J.; Kuhlmann, H. Methods to estimate on-field nitrogen emissions from crop production as an input to LCA studies in the agricultural sector. Intern. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2000, 5, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christelle, R.; Pflimlin, A.; Le Gall, A. Optimisation of environmental practices in a network of dairy farms of the Atlantic Area. In Proceedings of the Final Seminar of the Green Dairy Project, Rennes, France, 13–14 December 2006; pp. 43–65. [Google Scholar]

- NRC. Nutrient Requirements of Small Ruminants: Sheep, Goats, Cervids and World Camelids, 6th ed.; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; p. 384. [Google Scholar]

- Agricultural Research Council (ARC). The Nutrient Requirements of Ruminant Livestock; The Gresham Press: London, UK, 1980; p. 351. [Google Scholar]

- Ogejo, J.A.; Wildeus, S.; Knight, P.; Wilke, R.B. Estimating goat and sheep manure production and their nutrient contribution in the Chesapeake Bay Watershed. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2020, 26, 1061–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Prado Santeodoro, A.; Baucells Ribas, J.; Casasús Pueyo, I.; Fondevila Camps, M. Bases Zootécnicas Para el Cálculo del Balance Alimentario de Nitrógeno y Fósforo en Ovino; Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación: Madrid, Spain, 2019; p. 97. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- De Vries, J.W.; Hoeksma, P.; Groenestein, C.M. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) mineral concentrates pilot. Wagening. UR Livest. Res. 2011, 480, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Goossensen, F.R.; Van Den Ham, A. Equations to calculate nitrate leaching. In Publicatie No. 33; Information and Knowledge Centre: Ede, The Netherlands, 1992; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Schils, R.; Oudendag, D.; van der Hoek, K.; de Boer, J.; Evers, A.; de Haan, M. Broeikasgas Module BBPR; Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu RIVM: Bilthoven, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Velthof, G.L.; Mosquera, J. Calculations of Nitrous Oxide Emissions from Agriculture in The Netherlands: Update of Emission Factors and Leaching Fraction; Alterra: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Velthof, G.; Oenema, O. Nitrous oxide emission from dairy farming systems in the Netherlands. Neth. J. Agric. Sci. 1997, 45, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornthwaite, C.W. An approach toward a rational classification of climate. Geogr. Rev. 1948, 38, 55–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspar, H.F.; Tiedje, J.M. Dissimilatory reduction of nitrate and nitrite in the bovine rumen: Nitrous oxide production and effect of acetylene. Appl. Environ. Microb. 1981, 41, 705–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nielsen, P.H.; Nielsen, A.M.; Weidema, B.P.; Dalgaard, R.; Halberg, N. LCA Food Data Base; Danish Institute of Agricultural Sciences: Tjele, Denmark, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rotz, C.; Michael, S.; Chianese, D.; Montes, F.; Hafner, S.; Colette, C. The Integrated Farm System Model; Reference Manual, Version 3.6; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- IDF. A common carbon footprint approach for the dairy sector. The IDF guide to standard life cycle assessment methodology. Bull. Int. Dairy Fed. 2010, 445. [Google Scholar]

- Audsley, E.; Brander, M.; Chatterton, J.; Murphy-Bokern, D.; Webster, C.; Williams, A. How low can we go? An assessment of greenhouse gas emissions from the UK food System and the scope for to reduction them by 2050. Food Clim. Res. Netw. 2009, 80. [Google Scholar]

- Battini, F.; Agostini, A.; Tabaglio, V.; Amaducci, S. Environmental impacts of different dairy farming systems in the Po Valley. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapagain, A.K.; Hoekstra, A.Y. Virtual Water Flows between Nations in Relation to Trade in Livestock and Livestock Products; UNESCO-IHE: Delft, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Chapagain, A.K.; Hoekstra, A.Y. Water Footprints of Nations; UNESCO-IHE: Delft, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Mekonnen, M.; Hoekstra, A. A global assessment of the water footprint of farm animal products. Ecosystems 2012, 15, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thomson, A.J.; King, J.A.; Smith, K.A.; Tiffin, D.H. Opportunities for Reducing Water Use in Agriculture; Defra Research: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bos, J.; de Haan, J.; Sukkel, W.; Schils, R. Energy use and greenhouse gas emissions in organic and conventional farming systems in the Netherlands. NJAS Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2014, 68, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ausdley, E.; Alber, S.; Clift, R.; Cowell, S.; Crettaz, P.; Gaillard, G.; Hausheer, J.; Jolliet, O.; Kleijn, R.; Mortensen, B.; et al. Harmonization of Environmental Life Cycle Assessment for Agriculture. In Final Report, Concerted Action AIR3-CT94-2028; European Commission DG VI: Brussels, Belgium, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Weidema, B.P.; Mortensen, B.; Nielsen, P.; Hauschild, M. Elements of an Impact Assessment of Wheat Production. Inst. Prod. Dev. 1996, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, M.A.; Billen, G.; Bleeker, A.; Erisman, J.W.; Grennfelt, P.; Grinsven, H.; Van Grizzetti, B.; Howard, C.M.; Leip, A. European Nitrogen Assessment—Technical summary. In The European Nitrogen Assessment; Sutton, M.A., Howard, C.M., Erisman, J.W., Billen, G., Bleeker, A., Grennfelt, P., van Grinsven, H., Grizzetti, B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; p. 664. [Google Scholar]

- Juárez, M.; Juárez, M.; Sánchez, A.; Jordá, J.D.; Sánchez, J.J. Diagnóstico del Potencial Nutritivo del Suelo; Publicaciones de la Universidad de Alicante: San Vicente del Raspeig, Spania, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J.E.; Undersander, D.J. Relative forage quality: an alternative to relative value and quality index. In Proceedings of the 13th Annual Florida Ruminant Nutrition Symposium, Gainesville, FL, USA, 11–12 January 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Legarra, A.; Ole, F.; Aguilar, I.; Misztal, I. Single Step, a general approach for genomic selection. Livest. Sci. 2014, 166, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, J.M.; Davies, D.R. The aerobic stability of silage: Key findings and recent development, Review paper. Grass Forage Sci. 2012, 68, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo, G.; Martínez-Suller, L.; Sarmiento, M. Efectos del color de plástico y número de capas sobre la composición química y calidad fermentativa en ensilados de hierba y veza-avena. In La Multifuncionalidad de los Pastos: Producción Ganadera Sostenible y Gestión de los Ecosistemas; Sociedad Española para el Estudio de los Pastos: Madrid, Spain, 2009; pp. 279–286. [Google Scholar]

- Ramón, M.; Díaz, C.; Pérez-Guzman, M.D.; Carabaño, M.J. Effect of exposure to adverse climatic conditions on production in Manchega dairy sheep. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 5764–5779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finocchiaro, R.; van Kaam, J.B.; Portolano, B.; Misztal, I. Effect of heat stress on production of Mediterranean dairy sheep. J. Dairy Sci. 2005, 88, 1855–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patra, A.K. Aspects of nitrogen metabolism in sheep-fed mixed diets containing tree and shrub foliages. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 1319–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhao, Y.G.; Gordon, A.W.; O´Connell, N.E.; Yan, T. Nitrogen utilization efficiency and prediction of nitrogen excretion in sheep offered fresh perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne). J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 94, 5321–5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverley, C.; Ward, K.; Smith, N.; Gibbs, G.J.; Muir, P. Effect of feeding time on urinary and faecal nitrogen excretion patterns in sheep. J. Agric. Res. 2021, 64, 314–319. [Google Scholar]

- Mushtaq, A.; Gul, Z.; Mir, S.D.; Dar, Z.A.; Dar, S.H.; Shahida, I.; Bukhari, S.A.; Khan, G.H.; Asima, G. Estimation of correlation coefficient in oats (Avena sativa L.) for forage yield, grain yield and their contributing traits. Int. J. Plant Breed. Genet. 2013, 7, 188–191. [Google Scholar]

- Bilal, M.; Ayub, M.; Tariq, M.; Tahir, M.; Nadeem, M.A. Dry matter yield and forage quality traits of oat (Avena sativa L.) under integrative use of microbial and synthetic source of nitrogen. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2017, 16, 326–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación. Anuario Estadística Agraria; Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, M.; Smith, P.; Wilkinson, J.M. Mitigating climate change: The role of domestic livestock. Animal 2010, 4, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hegarty, R.S.; Alcock, D.; Robinson, D.L.; Goopy, J.P.; Vercoe, P.E. Nutritional and flock management options to reduce Methane output and Methane per unit product from sheep enterprises. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2010, 50, 1026–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.K.; Jones, D.L.; Cross, P. The carbon footprint of UK sheep production: Current knowledge and opportunities for reduction in temperate zones. J. Agric. Sci. 2014, 152, 288–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibata, M.; Terada, F. Factors affecting Methane production and mitigation in ruminants. Anim. Sci. J. 2010, 81, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, A.; Terré, M.; Vidal, M. Symposium review: Decomposing efficiency of milk production and maximizing profit. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 5709–5725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thompson, L.R.; Rowntree, J.E. Invitado Review: Methane sources, quantification, and mitigation in grazing beef systems. Appl. Anim. Sci. 2020, 36, 556–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruickshank, G.J.; Thomson, B.C.; Muir, P.D. Modelling Management Change on Production Efficiency and Methane Output within a Sheep Flock; Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry: Wellington, New Zealand, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Castanheira, É.G.; Freire, F. Greenhouse gas assessment of soybean production: Implications of land use change and different cultivation systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 54, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schader, C.; Jud, K.; Meier, M.S.; Kuhn, T.; Oehen, B.; Gattinger, A. Quantification of the effectiveness of greenhouse gas mitigation measures in Swiss organic milk production using a life cycle assessment approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 73, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnegan, W.; Goggins, J.; Chyzheuskaya, A.; Zhan, X. Global warming potential associated with Irish milk powder production. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2017, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buddle, B.M.; Denis, M.; Attwood, G.T.; Altermann, E.; Janssen, P.H.; Ronimus, R.S.; Piñares-Patiño, C.S.; Muetzel, S.; Wedlock, D.N. Strategies to reduce Methane emissions from farmed ruminants grazing on pasture. Vet. J. 2011, 188, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Mara, F.P.; Beauchemin, K.A.; Kreuzer, M.; Mcallister, T.A. Reduction of greenhouse gas emissions of ruminants through nutritional strategies. In Livestock and Global Climate Change, Proceedings of the International Conference, Hammamet, Tunisia, 17–20 May 2008; Rowlinson, P., Steele, M., Nefzaoui, A., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008; pp. 40–43. [Google Scholar]

| Sources of Variation (Baseline) | Manchega | Foreigners | Florida |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total, ha | 1013 | 157 | 218 |

| Animals | 1466 | 1466 | 228 |

| Lactating animals | 838 | 1197 | 122 |

| Non-lactating animals | 634 | 248 | 106 |

| Replacement animals | 414 | 489 | 52 |

| Milk, liters or FPCM per head and year | 282 | 497 | 467 |

| Purchased fodder, kg ha−1 | 450 | 4120 | 238 |

| Purchased concentrates, kg ha−1 | 533 | 7147 | 484 |

| Grazing occupation, % | 17 | 3 | 11 |

| Feeding stuffs | OH; AlH,CS,Ba,Con | OH; AlH,CS,Ba,Con | OH; AlH,CS,Ba,Con |

| Fertilizers, kg of N per ha | 24.6 | 27.7 | 11.1 |

| Fertilizers, kg of P per ha | 7.6 | 7.7 | 0.13 |

| Fertilizers, kg of K per ha | 5.2 | 7.6 | 0.13 |

| CO2e, kg per ha−1 and per year | 1655 | 12,634 | 1198 |

| CO2e, kg per LU and per year | 6397 | 7510 | 6507 |

| CO2e, kg per liter of FPCM | 3.78 | 2.77 | 3.06 |

| Breed | Group | Scenario |

|---|---|---|

| Manchega | Genetic improvement | 5% genetic value |

| 10% genetic value | ||

| 15% genetic value | ||

| Manchega Foreigners Florida | Animals inventory | <10% unproductive females |

| <5% replacement | ||

| <5% dead offspring | ||

| <5% deaths of lactating animals | ||

| Manchega Foreigners Florida | Purchased Feed | Soybean replacement by peas in food |

| Replacement of feedstuffs by fibrous ones | ||

| Natural breastfeeding × automatic breastfeeding | ||

| Manchega Foreigners | Forage Management | Substitution of 25% land oat (silage round bale) × vetch |

| Substitution of 25% land oat (silage bags) × vetch | ||

| Triticale grazing 100 days A | ||

| <15% of fodder grains and triticale grazing A | ||

| Substitution of oat hay (113 RFQ vs. 139) | ||

| Manchega Foreigners Florida | Electrical supply | Reduce 10% milking energy |

| Manchega | Climate change | Temperature increase + 2 °C |

| Sources of Variation | Manchega (M = 25) (Value (sd)) | Foreigners (F = 6) (Value (sd)) | Florida (C = 5) (Value (sd)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Land | |||

| Total, n◦ has | 1013 (814) | 157 (215) | 218 (339) |

| Arable, n◦ has | 164 (168) | 78 (88) | 9 (7) |

| Fallow land, n◦ has | 67 (93) | 27 (48) | 2 (2) |

| Agricultural cereals (G), n◦ has | 40 (51) | 28 (57) | 4 (3) |

| Agricultural cereals (F), n◦ has | 35 (40) | 38 (50) | 4 (6) |

| Maize, n◦ has | 6 (22.7) | - | - |

| Legumes, n◦ has | 16 (23.8) | - | - |

| Communal pastures, n◦ has | 849 (843) | 79 (159) | 209 (338) |

| Forages and grains production per farmland (hectare) | |||

| Alfalfa, t DM ha−1 | 14.7 (3.6) | - | - |

| Maize, t DM ha−1 | 15.7 (2.8) | - | - |

| Oat, t DM ha−1 | 4.9 0.9) | 5.0 (0.3) | 5.1 (0.3) |

| Triticale, t DM ha−1 | 4.6 (0.3) | 5.1 (0.1) | - |

| Vetch, t DM ha−1 | 5.2 (0.3) | - | - |

| Peas, t DM ha−1 | 3.7 (2.0) | - | - |

| Barley grain, t DM ha−1 | 2.9 (0.7) | 3.0 (0.1) | 2.5 (0.2) |

| Fertilizers per farmland (hectare) | |||

| Fertilizers, kg N ha−1 | 24.6 (37.2) | 27.7 (42.7) | 11.1 (17.5) |

| Fertilizers, kg P ha−1 | 7.6 (25.7) | 7.7 (11.8) | 0.13 (0.21) |

| Fertilizers, kg K ha−1 | 5.2 (14.9) | 7.6 (11.8) | 0.13 (0.21) |

| Animals | |||

| Total, n | 1466 (980) | 1446 (1162) | 228 (85) |

| Lactating female, n | 838 (558) | 1199 (950) | 122 (42) |

| Flock Replacement, n | 414 (326) | 489 (470) | 52 (29) |

| Flock Replacement, % | 26.9 (7.7) | 30.6 (6.9) | 21.6 (5.5) |

| Stocking Density, LU ha−1 | 1.12 (2.1) | 129.7 (170) | 9.4 (15,4) |

| Feed | |||

| Ingested, kg DM PF year−1 | 1025 (141) | 1066 (166) | 790 (51) |

| Purchased forage, kg DM PF year−1 | 236 (119) | 338 (90) | 250 (148) |

| Purchased concentrate, kg DM PF year−1 | 304 (44) | 586 (143) | 430 (59) |

| Own forage, kg DM PF year−1 | 449 (203) | 93 (114) | 109 (120) |

| Own concentrate, kg DM PF year−1 | 36 (44) | 49 (88) | . |

| Grazing time per year, % | 27.9 (14.1) | 3.7 (7.1) | 16.5 (17.1) |

| Meat and milk yield | |||

| Milk FPCM, t farm A | 393.7 (234) | 691.8 (632) | 79.6 (21.8) |

| Milk FPCM, t ha−1 B | 1.5 (2.6) | 285.4 (371) | 17.4 (29.4) |

| Milk FPCM, liters per PF 1 B | 307 (76) | 479 (94) | 381 (63) |

| Offspring born, ha | 9 (18.1) | 1021 (1352) | 57 (105) |

| Offspring slaughtered for meat, ha C | 4.6 (9.5) | 443 (559) | 33.6 (52) |

| Cull animals, ha | 1.1 (2.4) | 121 (164) | 11.8 (19) |

| Live weight sold, kg ha year−1 | 85.7 (180) | 8664 (11,072) | 671 (1057) |

| Efficiency | |||

| LU | 4.7 (1.8) | 4.5 (1.9) | 3 (0) |

| Marketed milk FPCM, t LU−1 | 80.5 (30.7) | 131.9 (69.8) | 26.5 (7.3) |

| Cheese extract, t LU−1 | 11.5 (4.1) | 16.5 (9.5) | 2.3 (0.7) |

| Live weight sold, t LU−1 | 4.9 (1.6) | 4.8 (1.3) | 1.1 (0.7) |

| Liters FPCM kg−1 DM ingested D | 0.30 (0.07) | 0.46 (0.13) | 0.48 (0.06) |

| Liters FPCM kg−1 DM milking E | 0.60 (0.20) | 0.72 (0.20) | 0.78 (0.15) |

| NUE farm, % | 22.5 (10.8) | 16.3 (3.8) | 25.9 (15.3) |

| NUE milk-lactating females, % | 20.3 (6.3) | 15.5 (3.9) | 21.5 (7.6) |

| NUE milk+meat all animals together % | 33.5 (7.5) | 29.3 (4.8) | 34.1 (9.0) |

| Animal Model | Data Set | Characteristics of the Independent Variables | |||||

| Non-Standardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | Collinearity Diagnosis | |||||

| Independent variables | Mean | sd | β | se | β | Tol | VIF |

| Replacement females (4–12 months) | |||||||

| Constant | −136.7 ** | 61.6 | |||||

| Present Female | 1267 | 873 | 0.42 *** | 0.04 | 0.809 | 1 | 1 |

| Born lambs and kids | |||||||

| Constant | −112.1 NS | 89.1 | |||||

| Present Female | 1267 | 873 | 1.91 *** | 0.058 | 0.974 | 1 | 1 |

| Culled lambs and kids | |||||||

| Constant | 91.4 NS | 75.8 | |||||

| Present Female | 1267 | 873 | 0.98 *** | 0.049 | 0.936 | 1 | 1 |

| Losses, deaths, discards (breeding ewes/goats) | |||||||

| Constant | −122.6 NS | 74.0 | |||||

| Present Female | 1267 | 873 | 0.4 *** | 0.04 | 0.904 | 1 | 1 |

| Lambs and kids deaths, abortions, etc. | |||||||

| Constant | −117.2 NS | 101.2 | |||||

| Present Female | 1267 | 873 | 0.55 *** | 0.068 | 0.768 | 1 | 1 |

| Feces, Urine and N Excretion Model (per Head and Day) | Data Set | Characteristics of the Independent Variables | |||||

| Non-Standardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | Collinearity Diagnosis | |||||

| Independent variables | Mean | sd | β | se | β | Tol | VIF |

| Faeces, g d−1 | |||||||

| Constant | 512.7 *** | 18.5 | |||||

| OMD | 0.633 | 0.10 | −699.1 *** | 27.3 | −0.726 | 0.905 | 1.1 |

| DM intake, g sheep d−1 | 791.5 | 186 | 0.084 * | 0.043 | 0.160 | 0.100 | 9.2 |

| GP intake, g sheep d−1 | 143.8 | 60.6 | 0.579 *** | 0.083 | 0.357 | 0.279 | 3.59 |

| NDF intake, g sheep d−1 | 386.7 | 104.9 | 0.269 *** | 0.067 | 0.288 | 0.143 | 7.00 |

| Model volume urine, cc d−1 | |||||||

| Constant | −654.1 *** | 74.7 | |||||

| N intake, g d−1 | 20.9 | 8.5 | 71.3 *** | 3.51 | 0.752 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| N feces, g d−1 | |||||||

| Constant | 1.30 *** | 0.149 | |||||

| N intake, g d−1 | 20.9 | 8.5 | 0.241 *** | 0.007 | 0.852 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| N urine, g d−1 | |||||||

| Constant | 1.95 *** | 0.482 | |||||

| N intake, g d−1 | 20.9 | 8.5 | 0.64 *** | 0.021 | 0.804 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Forage Production Model | Data Set | Characteristics of the Independent Variables | |||||

| Non-Standardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | Collinearity Diagnosis | |||||

| Independent variables | Mean | sd | β | se | β | Tol | VIF |

| Triticale, kg DM ha−1 | |||||||

| Constant | −11,052 *** | 833 | |||||

| Height, cm | 82.4 | 18.22 | 133.2 *** | 4.86 | 0.926 | 0.97 | 1.02 |

| Days to inflorescence emergence | 154.2 | 36.5 | 33.9 *** | 3.56 | 0.471 | 0.45 | 2.19 |

| kg N ha−1 background | 23.8 | 14.1 | 62.9 *** | 9.21 | 0.339 | 0.45 | 2.20 |

| Oats, kg DM ha−1 | |||||||

| Constant | 2632 *** | 561.7 | |||||

| Height, cm | 70.5 | 28.0 | 112.6 *** | 7.4 | 0.935 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Model | n | se | R2 | D-W | Observed | Simulated | d | R2 | RMSE | MBE | EF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal | ||||||||||||

| Replacement females (4–12 months) | −136.7 + (0.42 PF) | 61 | 271 | 0.65 | 2.08 | 400 | 406 | 0.98 | 0.93 | 1.88 | −0.86 | 0.93 |

| Born lambs and kids | −112.1 + (1.91 PF) | 61 | 392 | 0.95 | 1.89 | 2343 | 2238 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 4.72 | 2.43 | 0.97 |

| Culled lambs and kids | 91.4 + (0.97 PF) | 61 | 326 | 0.87 | 2.18 | 1329 | 1355 | 0.98 | 0.92 | 4.26 | 1.06 | 0.91 |

| Losses, deaths, discards (breeding ewes/goats) | 122.6 + (0.40 PF) | 19 | 189 | 0.80 | 1.54 | 284 | 329 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 3.45 | −3.1 | 0.92 |

| Lambs’ and kids’ deaths, abortions, etc. | −117.2 + (0.55 PF) | 48 | 377 | 0.59 | 1.84 | 578 | 565 | 0.96 | 0.92 | 4.58 | 1.06 | 0.85 |

| Lambs and kids live weight on slaughter A-B | 272 | - | 0.95 | - | 50.1 | 48.4 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.0079 | −5.69 | 0.99 | |

| Urine and Fecal N Excretion per Head and per Day | ||||||||||||

| Feces, g DM C-D | 523-(692.6 OMD/100) + (0.084 g DM ingested d−1) + (0.57 g GP d−1) +(0.269 * g NDF d−1) | 510 | 59.3 | 0.64 | 1.31 | 322.5 | 320.4 | 0.87 | 0.63 | 0.11 | 3.26 | 0.63 |

| Urine, ml C-D | −654.1 + (71.3 g N d−1) | 313 | 529 | 0.56 | 0.85 | 757 | 751 | 0.84 | 0.74 | 1.7 | 2.43 | 0.66 |

| N faeces, g C-D | 1.30 + (0.24 g N d−1) | 510 | 1.26 | 0.78 | 0.99 | 6.38 | 6.35 | 0.97 | 0.72 | 0.0025 | 1.98 | 0.99 |

| N urine, gC-D | 1.95 + (0.64 g N d−1) | 313 | 4.06 | 0.64 | 0.75 | 15.6 | 15.4 | 0.87 | 0.64 | 0.008 | −5.6 | 0.90 |

| N feces, g E | 0.16 + (0.3 g N ingested kg live weight0.75) | 0.065 | 0.91 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| N urine, g E | −0.0061 + (0.31 g N ingested kg live weight0.75) | 0.06 | 0.98 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Forage Production | ||||||||||||

| Triticale, kg DM ha−1 | −11,952 + (133.2 Height, cm) + (33.9 Days to inflorescence emergence ) + (62.9 kg N background) | 59 | 669 | 0.93 | 1.67 | 5903 | 5990 | 0.98 | 0.65 | 8.46 | 0.63 | 0.52 |

| Oats, kg DM ha−1 | −2632 + (112 Height, cm) | 35 | 1211 | 0.87 | 0.59 | 5311 | 5407 | 0.95 | 0.87 | 34.5 | 0.63 | 0.76 |

| Breed | Group | Scenario | CO2e kg/ha | Change% | CO2e kg/LU | Change % | CO2e kg/liter FPCM | Change % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manchega | Baseline | − | 1655 | 6397 | 3.78 | |||

| Foreigners | − | 12,634 | 7510 | 2.77 | ||||

| Florida | − | 1198 | 6507 | 3.06 | ||||

| 5% genetic value | 1652 | −0.17 | 6387 | −0.17 | 3.77 | −0.17 | ||

| Manchega | Genetics | 10% genetic value | 1631 | −1.45 | 6356 | −0.65 | 3.73 | −1.37 |

| 15% genetic value | 1625 | −1.81 | 6411 | 0.21 | 3.72 | −1.60 | ||

| Manchega | Animal inventory | < 5% replacement | 1454 | −12.1 | 5620 | −12.1 | 3.78 | −0.17 |

| < 5% offspring deaths | 1656 | 0.03 | 6399 | 0.03 | 3.76 | −0.59 | ||

| < 5% lactating animals deaths | 1454 | −12.1 | 5620 | −12.1 | 3.76 | −0.56 | ||

| < 10% empty females | 1616 | −2.38 | 6456 | 0.92 | 3.71 | −2.05 | ||

| Foreigners | < 5% replacement | 11,357 | −10.1 | 6751 | −10.1 | 2.77 | −0.11 | |

| < 5% offspring deaths | 12,637 | 0.02 | 7512 | 0.02 | 2.77 | −0.33 | ||

| < 5% lactating animals deaths | 11,408 | −9.70 | 6706 | −10.1 | 2.77 | −0.21 | ||

| < 10% empty females | 12,535 | −0.78 | 7562 | 0.69 | 2.76 | −0.69 | ||

| Florida | < 5% replacement | 1012 | −15.5 | 5497 | −15.5 | 3.07 | 0.20 | |

| < 5% offspring deaths | 1036 | −13.5 | 5627 | −13.5 | 3.07 | 0.29 | ||

| < 5% lactating animals deaths | 1218 | 1.65 | 6539 | 0.50 | 3.07 | 0.38 | ||

| < 10% empty females | 1164 | −2.82 | 6599 | 1.42 | 2.98 | −2.82 | ||

| Manchega | Milk replacer | 1775 | 7.25 | 6861 | 7.25 | 4.42 | 16.7 | |

| Purchased feed | Soybean x peas | 1435 | −13.2 | 5548 | −13.2 | 3.28 | −13.2 | |

| Conventional vs. fibrous feedstuffs | 1862 | 12.5 | 7198 | 12.5 | 4.26 | 12.5 | ||

| Milk replacer | 13,390 | 5.99 | 7960 | 5.99 | 3.08 | 11.1 | ||

| Foreigners | Soybean x peas | 10,471 | −17.1 | 6225 | −17.1 | 2.30 | −17.1 | |

| Conventional vs. fibrous feedstuffs | 15,867 | 25.5 | 9432 | 25.5 | 3.48 | 25.5 | ||

| Milk replacer | 1292 | 7.88 | 7019 | 7.88 | 3.44 | 12.2 | ||

| Florida | Soybean x Peas | 961 | −19.7 | 5219 | −19.7 | 2.46 | −19.7 | |

| Conventional vs. fibrous feedstuffs | 1430 | 19.3 | 7768 | 19.3 | 3.66 | 19.3 | ||

| Manchega | Forage Management | Oat hay RFV 113 vs. 139 | 1427 | −13.7 | 5516 | −13.7 | 3.78 | −0.08 |

| Grazing triticale 100 days | 1417 | −14.3 | 5477 | −14.4 | 3.80 | 0.39 | ||

| < 15% high-protein feedstuffs and triticale grass | 1632 | −1.41 | 6307 | −1.41 | 3.73 | −1.41 | ||

| < 25% aurface V-O (hay x bag silage) and vetch | 1621 | −2.04 | 6267 | −2.04 | 3.71 | −2.04 | ||

| < 25% surface V-O (hay x silage round bales) and vetch | 1655 | 0.00 | 6398 | 0.00 | 3.79 | 0.00 | ||

| Foreigners | Oat hay RFV 113 vs. 139 | 12,565 | −0.55 | 7469 | −0.55 | 2.76 | −0.55 | |

| < 25% surface V-O (hay x bag silage) and Vetch | 10,471 | −17.1 | 6225 | −17.1 | 2.30 | −17.1 | ||

| < 25% surface V-O (hay x silage round bales) and vetch | 15,867 | 25.5 | 9732 | 25.5 | 3.48 | 25.5 | ||

| Florida | Oat hay RFV 113 vs. 139 | 1001 | −16.4 | 5437 | −16.4 | 3.08 | 0.45 | |

| Manchega | Electrical supply | 1653 | −0.15 | 6388 | −0.15 | 3.78 | −0.15 | |

| Foreigners | < 10% milking time | 12,622 | −0.10 | 7503 | −0.10 | 2.77 | −0.10 | |

| Florida | 1012 | −15.5 | 5497 | −15.5 | 3.07 | 0.11 | ||

| Manchega | Room temperature increase | +2.0 °C | 1659 | 0.22 | 6412 | 0.22 | 3.84 | 1.46 |

| Foreigners | 12,754 | 0.95 | 7581 | 0.95 | 2.79 | 0.51 | ||

| Florida | 1201 | 0.28 | 6525 | 0.28 | 3.08 | 0.70 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salcedo, G.; García, O.; Jiménez, L.; Gallego, R.; González-Cano, R.; Arias, R. GHG Emissions from Dairy Small Ruminants in Castilla-La Mancha (Spain), Using the ManleCO2 Simulation Model. Animals 2022, 12, 793. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12060793

Salcedo G, García O, Jiménez L, Gallego R, González-Cano R, Arias R. GHG Emissions from Dairy Small Ruminants in Castilla-La Mancha (Spain), Using the ManleCO2 Simulation Model. Animals. 2022; 12(6):793. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12060793

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalcedo, Gregorio, Oscar García, Lorena Jiménez, Roberto Gallego, Rafael González-Cano, and Ramón Arias. 2022. "GHG Emissions from Dairy Small Ruminants in Castilla-La Mancha (Spain), Using the ManleCO2 Simulation Model" Animals 12, no. 6: 793. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12060793

APA StyleSalcedo, G., García, O., Jiménez, L., Gallego, R., González-Cano, R., & Arias, R. (2022). GHG Emissions from Dairy Small Ruminants in Castilla-La Mancha (Spain), Using the ManleCO2 Simulation Model. Animals, 12(6), 793. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12060793