“Not All Who Wander Are Lost”: The Life Transitions and Associated Welfare of Pack Mules Walking the Trails in the Mountainous Gorkha Region, Nepal

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

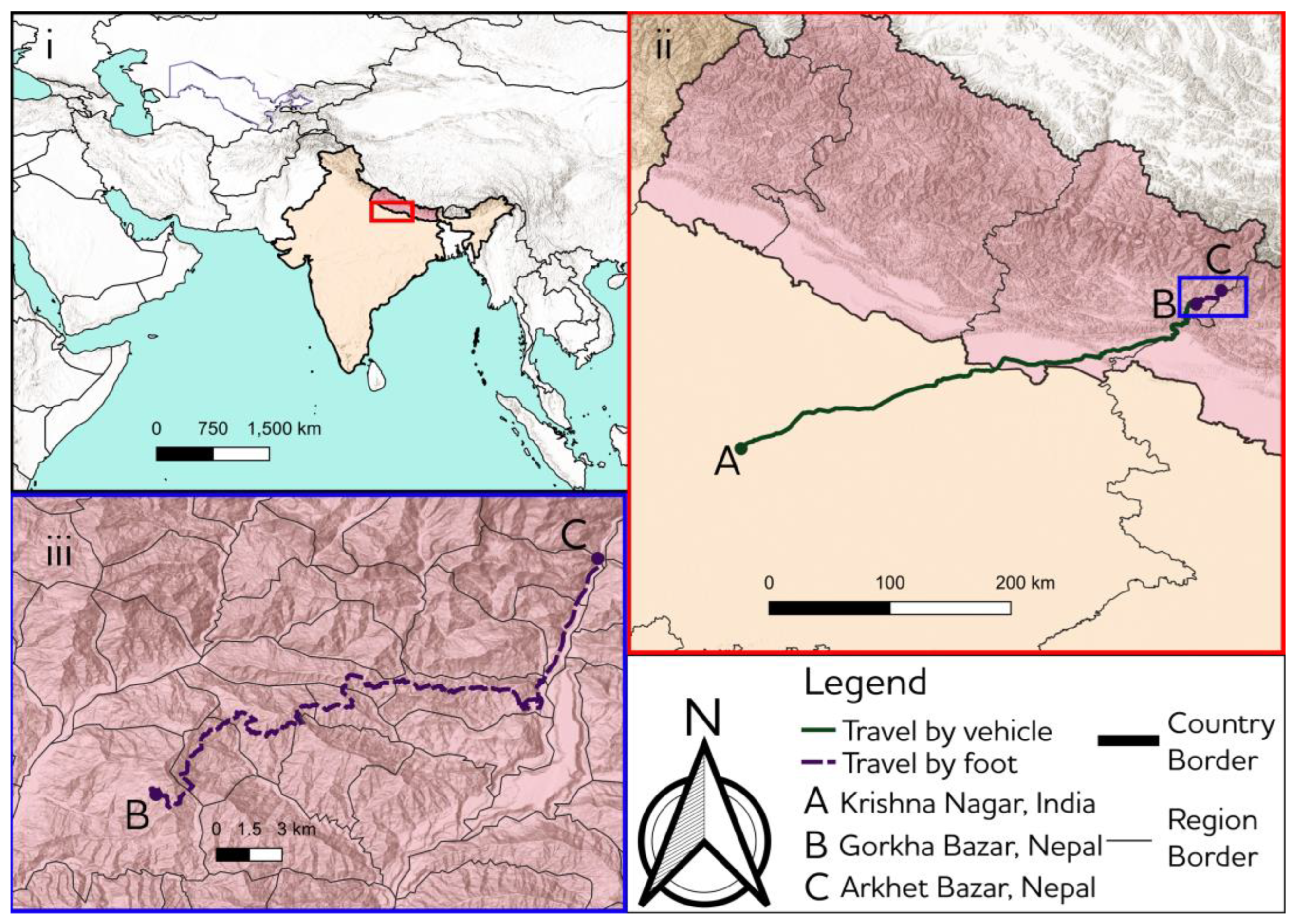

2.1. Study Sites

2.2. Participant Recruitment

2.3. Topographic Map

2.4. Data Collection

2.4.1. Quantitative Data—Livelihood Surveys

2.4.2. Quantitative Data—EARS Assessments

2.4.3. Qualitative Data—Semi-Structured Interviews

2.5. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Data

3.1.1. Livelihoods Survey

3.1.2. EARS Welfare Assessments

3.2. Qualitative Data

3.2.1. Transitions: Translocation/Transportation to Nepal

They [mules] have been working in India; in brick kilns […] if they [mules] work in India, then it is easier for them to work here.(Mule trader)

Just [one break in the journey] in Gorkha [Bazar] while we are coming to Gorkha [Bazar] there is a river and we stop them to have some water and food [unclear whether the food and water is for the mules or the trader].(Mule trader)

They bring in glanders [Glanders is a notifiable infectious disease mainly affecting Equidae, though other species, including humans, can get the disease [28]] the disease. The government restricted the entry of mules to this particular state (during glanders outbreaks) from Uttar Pradesh, so they [the traders and migratory workers with mules] walked [to avoid detection]. They come in somehow, we don’t know how, illegally, but we don’t know how they get here.(Veterinarian AN)

3.2.2. Transitions: Adaptation to New Surroundings, Handling and Training

[…] they do not know the working route—they are not habituated initially so three or four fell down on the route.(Mule owner)

Yeah they needed training because there is a vast difference between carrying loads in the brick factory and carrying loads over here. In the brick kiln, they only work for five to ten minute distance, and they have a sack in both side like a bag, so it is easier for them. But putting loads on the [pack] saddle it’s a different thing and tying them and walking in a very narrow road, it’s very different so need to be with two or three person [guiding them] before otherwise it will be very hard for them to carry over here.(Mule owner)

It takes almost one month for them to train and they need to learn how to work the curved routes [winding trails], and they need to know where to jump, how to cross the small rivers and to learn how to carry loads, they jump a lot when we first load them.(Mule owner)

If a mule sweats and cannot walk the load is too heavy.(Mule owner)

3.2.3. Transitions: Adjustment to Environmental Conditions

During the monsoons you need to take care of the mules with extra things, it’s just like humans we need good food after work so I give them good food […]. You have to take care of their feet properly during the monsoon, if you do that your mules are going to be alright in every season […], even during the cold season I give them honey and eggs. When you reach up there [further up into the mountain ranges] in the cold I give them Kukuri [a Nepalese brand] rum to save them from the cold.(Mule owner)

I can’t let my animals graze up there because of the [potential for] landslide and even down there [lower in the valley] the rivers will grow so what I do is I just make a rope here and pull around the tent so they can be safe. I save my animals like that but some other mule owners they let them [loose] wherever they are and so that’s the reason their feet are under the ground in all the mud and even their body are all wet so they get sick very frequently […]. In my opinion, we shouldn’t use our animals because the feet get hurt most at that time and most of them limp so from this monsoon, I try to decrease my movement of my animals to save them […].(Mule owner)

It’s very dangerous during the monsoons, so when you work [the mules] through there [monsoon] I think I might die and my mules might die I keep on thinking that, it’s very, very difficult.(Mule owner)

[When there is bad weather] it affects us a lot because if we are going up and its rained we have to stop there, eat there, stay there […]. If there is no snow they can go up, but cannot go to Larkye Pass and Tibet […] as we cannot reach to our end place [destination] we have to leave everything in between the way [at a location on the trail set up for storing goods].(Mule owner)

So when we are up there [at high altitude] it [mule] show the signs of headache and some walk very fast when they have a headache and some people cannot work [the people also get altitude sickness], then we can tell they have an altitude sickness or something like. Somebody get medicine in some animals it works, in some it doesn’t and they die […] so we try to treat it, we give them garlic and hot water and some alcohol.(Mule owner)

4. Discussion

4.1. Translocation and Transportation

4.2. Adaptation to New Surroundings, Handling and Training

4.3. Adjustment to Environmental Conditions

4.4. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hawson, L.A.; McLean, A.N.; McGreevy, P.D. The roles of equine ethology and applied learning theory in horse-related human injuries. J. Vet. Behav. 2010, 5, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, T.Q.; Brown, A.F. Champing at the Bit for Improvements: A Review of Equine Welfare in Equestrian Sports in the United Kingdom. Animals 2022, 12, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGreevy, P.D.; Oddie, C.; Burton, F.L.; McLean, A.N. The horse-human dyad: Can we align horse training and handling activities with the equid social ethogram? Vet. J. 2009, 181, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGreevy, P.; Christensen, J.W.; Von Borstel, U.K.; McLean, A. Equitation Science, 2nd ed.; Joh Wiley and Sons: Chichester, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Clough, H.; Roshier, M.; England, G.; Burford, J.; Freeman, S. Qualitative study of the influence of horse-owner relationship during some key events within a horse’s lifetime. Vet. Rec. 2021, 188, e79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luna, D.; Tadich, T.A. Why Should Human-Animal Interactions Be Included in Research of Working Equids’ Welfare? Animals 2019, 9, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesimple, C. Indicators of Horse Welfare: State-of-the-Art. Animals 2020, 10, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagos, J.; Rojas, M.; Rodrigues, J.B.; Tadich, T. Perceptions and Attitudes towards Mules in a Group of Soldiers. Animals 2021, 11, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horseman, S.; Whay, H.R.; Mullan, S.; Knowles, T.; Barr, A.R.; Buller, H. Horses in Our Hands; University of Bristol: Bristol, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rushen, J.; Taylor, A.A.; de Passillé, A.M. Domestic animals’ fear of humans and its effect on their welfare. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1999, 65, 285–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, S.F.; McLean, A.K.; Mahmoud, H.F.F. Welfare Assessment and Identification of the Associated Risk Factors Compromising the Welfare of Working Donkeys (Equus asinus) in Egyptian Brick Kilns. Animals 2020, 10, 1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohlich, N.; Sells, P.D.; Sommerville, R.; Bolwell, C.F.; Cantley, C.; Martin, J.E.; Gordon, S.J.G.; Coombs, T. Welfare Assessment and Husbandry Practices of Working Horses in Fiji. Animals 2020, 10, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, J.C.; Lindberg, A.C.; Main, D.C.; Whay, H.R. Assessment of the welfare of working horses, mules and donkeys, using health and behaviour parameters. Prev. Vet. Med. 2005, 69, 265–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfensohn, S. Too Cute to Kill? The Need for Objective Measurements of Quality of Life. Animals 2020, 10, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanie, M.; Fentahun, T.; Mitiku, T.; Malede, B. Strategies for Improvement of Draft Animal Power Supply for Cultivation in Ethiopia: A Review. Eur. J. Biol. Sci. 2012, 4, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Dwivedi, S.K.; Malik, P.; Panisup, A.S.; Tandon, S.N.; Singh, B.K. Mortality associated with heat stress in donkeys in India. Vet. Rec. 2010, 166, 143–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayo, J.O.; Olaifa, F.H.; Ake, A.S. Physiological responses of donkeys (Equus asinus, Perissodactyla) to work stress and potential ameliorative role of ascorbic acid. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2013, 12, 1585–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, R. Farming Animals and the Capabilities Approach: Understanding Roles and Responsibilities through Narrative Ethics. Soc. Anim. 2009, 17, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, F.H.; Hockenhull, J.; Pritchard, J.C.; Waterman-Pearson, A.E.; Whay, H.R. Behavioural repertoire of working donkeys and consistency of behaviour over time, as a preliminary step towards identifying pain-related behaviours. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AN. Supporting Mountain Mules “A Survey on Working Mules of Gorkha”; Animal Nepal: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2016; Available online: https://animalnepal.files.wordpress.com/2016/02/assesment-of-mountain-mules-gorkha-district.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2022).

- Raw, Z.; Rodrigues, J.B.; Rickards, K.; Ryding, J.; Norris, S.L.; Judge, A.; Kubasiewicz, L.M.; Watson, T.L.; Little, H.; Hart, B.; et al. Equid Assessment, Research and Scoping (EARS): The Development and Implementation of a New Equid Welfare Assessment and Monitoring Tool. Animals 2020, 10, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, C.; Lerer, A.; Anokwa, Y.; Tseng, C.; Brunette, W.; Borriello, G. Open data kit. In Proceedings of the 4th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development—ICTD ‘10, New York, NY, USA, 13–16 December 2010; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- ESRI. World Topographic Map. Available online: https://services.arcgisonline.com/ArcGIS/rest/services/World_Topo_Map/MapServer (accessed on 11 April 2022).

- QGIS. QGIS geographic information system. 2016. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. Available online: https://www.qgis.org/en/site/ (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- GADM. GADM database of Global Administrative Areas. 2012. Available online: https://gadm.org/ (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- G.M. Krishna Nagar to Arkhet Bazar. 2022. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps/@52.5008896,-3.2538624,14z (accessed on 12 April 2021).

- GOI. The Motor Vehicles (Amendment) Act 2015. 2015. Available online: https://prsindia.org/files/bills_acts/acts_parliament/2015/the-motor-vehicles-(amendment)-act,-2015.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- OIE. Glanders. Available online: https://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/Animal_Health_in_the_World/docs/pdf/Disease_cards/GLANDERS.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Weeks, C.A.; McGreevy, P.; Waran, N.K. Welfare issues related to transport and handling of both trained and unhandled horses and ponies. Equine Vet. Educ. 2012, 24, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damtew, A.; Erega, Y.; Ebrahim, H.; Tsegaye, S.; Msigie, D. The Effect of long Distance Transportation Stress on Cattle: A Review. Biomed. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2018, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Waran, N.; Leadon, D.; Friend, T. The effects of transportation on the welfare of horses. In The Welfare of Horses; Waran, N., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 125–150. [Google Scholar]

- Fazio, E.; Ferlazzo, A. Evaluation of Stress During Transport. Vet. Res. Commun. 2003, 27, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yorke, A.; Matusiewicz, J.; Padalino, B. How to minimise the transport-related behaviours in horses: A review. J. Equine. Sci. 2017, 28, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trent, N.; Edwards, S.; Felt, J.; O’Meara, K. International animal law, with a concentration on Latin America, Asia, and Africa. In The State of Animals III:2005; Salem, D.J., Rowan, A.N., Eds.; Humane Society Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 65–77. [Google Scholar]

- GOI. The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act, 1960. 1960. Available online: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/11237/1/the_prevention_of_cruelty_to_animals_act%2C_1960.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- AWBI. Transport of Animals Rules, 1978. 1978. Available online: http://awbi.in/awbi-pdf/TRANSPORT%20OF%20ANIMALS,%20RULES,%201978.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Welfare (AHAW); Nielsen, S.S.; Alvarez, J.; Bicout, D.J.; Calistri, P.; Canali, E.; Drewe, J.A.; Garin-Bastuji, B.; Gonzales Rojas, J.L.; Herskin, M.; et al. Welfare of equidae during transport. EFSA J. 2022, 20, e07444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EC. Guide to Good Practices for the Transport of Horses Destined for Slaughter. Available online: http://animaltransportguides.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/EN-Guides-Horses-final.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Padalino, B.; Raidal, S.L. Effects of Transport Conditions on Behavioural and Physiological Responses of Horses. Animals 2020, 10, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowles, T.G.; Brown, S.N.; Pope, S.J.; Nicol, C.N.; Warriss, P.D.; Weeks, C.A. The response of untamed (unbroken) ponies to conditions of road transport. Anim. Welf. 2010, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- GON. Animal Health and Livestock Services Act, 2055 (1999). Available online: https://lawcommission.gov.np/en/?cat=355 (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- AN. National and International Legal Instruments Addressing Animal Welfare in Nepal; Animal Nepal: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- AN. Nepalgunj Beasts of Burden Campaign; Animal Nepal: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IT. Horses’ Movement Banned in Peak Wedding Season in West Delhi due to Fear of Epidemic Outbreak. Available online: https://www.indiatimes.com/news/india/horses-movement-banned-in-peak-wedding-season-in-west-delhi-due-to-fear-of-epidemic-outbreak-336460.html (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Kubasiewicz, L.M.; Watson, T.L.; Nye, C.; Chamberlain, N.; Perumal, R.K.; Saroja, R.; Norris, S.L.; Raw, Z.; Burden, F.A. Bonded labour and equid ownership in the brick kilns of India, a need for reform of policy and practice. Anim. Welf. (Under Rev.) 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Padalino, B. Transport of Horses and Implications for Health and Welfare; University of Sydney: Sydney, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Tinker, M.K.; White, N.A.; Lessard, P.; Thatcher, C.D.; Pelzer, K.D.; Davis, B.; Carme, D.K. Prospective study of equine colic risk factors. Equine Vet. J. 1997, 29, 454–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillyer, M.H.; Taylor, F.G.R.; Proudman, C.J.; Edwards, G.B.; Smith, J.E.; French, N.P. Case control study to identify risk factors for simple colonic obstruction and distension colic in horses. Equine Vet. J. 2002, 34, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padalino, B.; Riley, C.B. Equine Transport. In The Behaviour and Welfare of the Horse; Riley, C.B., Cregier, S., Fraser, A.F., Eds.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2022; pp. 103–123. [Google Scholar]

- Leadon, D.; Waran, N.K.; Herholz, C.; Klay, M. Veterinary management of horse transport. Vet. Ital. 2008, 44, 149–163. [Google Scholar]

- Austin, S.M.; Foreman, J.H.; Hungerford, L.L. Case-control study of risk factors for development of pleuropneumonia in horses. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1995, 207, 325–328. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A.B.; Harris, P.A.; Barker, V.D.; Adams, A.A. Short-term transport stress and supplementation alter immune function in aged horses. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelps, E.A.; LeDoux, J.E. Contributions of the amygdala to emotion processing: From animal models to human behavior. Neuron 2005, 48, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandin, T.; Deesing, M. Humane Livestock Handling: Understanding Livestock Behaviour and Building Facilities for Healthier Animals, 1st ed.; Storey Publishing: North Adams, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.B.A.; El Sayed, M.A.; McLean, A.K.; Heleski, C.R. Aggression in working mules and subsequent aggressive treatment by their handlers in Egyptian brick kilns—Cause or effect? J. Vet. Behav. 2019, 29, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nye, C.; Watson, T.; Kubasiewicz, L.; Raw, Z.; Burden, F. No Prescription, No Problem! A Mixed-Methods Study of Antimicrobial Stewardship Relating to Working Equines in Drug Retail Outlets of Northern India. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, T.L.; Kubasiewicz, L.M.; Chamberlain, N.; Nye, C.; Raw, Z.; Burden, F.A. Cultural “Blind Spots”, Social Influence and the Welfare of Working Donkeys in Brick Kilns in Northern India. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, F.; Zappaterra, M.; Minero, M.; Bocchini, F.; Riley, C.B.; Padalino, B. Equine Transport-Related Problem Behaviors and Injuries: A Survey of Italian Horse Industry Members. Animals 2021, 11, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CIWF. Live Transport Common Problems and Practical Solutions; Compassion in World Farming: Godalming, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stull; Rodiek. Effects of cross tying horses during 24 h of road transport. Equine Vveterinary J. 2000, 34, 550–555. [Google Scholar]

- Broom, D.M. Causes of poor welfare in large animals during transport. Vet. Res. Commun. 2003, 27 (Suppl. S1), 515–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, F.; Mazzola, S.; Cannas, S.; Heinzl, E.U.L.; Padalino, B.; Minero, M.; Dalla Costa, E. Habituation to Transport Helps Reducing Stress-Related Behavior in Donkeys During Loading. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 593138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KP. Supreme Court Interim Order. Kathmandu Post, 27 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- GON. Animal Transportation Standards 2064 BS. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- GOI. The Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (Transport of Animals on Foot) Rules. 2001. Available online: http://www.dls.gov.np/downloadsdetail/4/2018/41339141 (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Lin, Z. Equus: Animal activists work for the welfare of Nepal’s mules and Donkeys. Nepali Times, 15–21 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- GON. Animal Welfare Directive 2073. 2016. Available online: https://www.animalnepal.org.np/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Animal-Welfare-Directive-2073-English.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Abdelbaset-Ismail, A.; Gugjoo, M.B.; Ghazy, A.; Gomaa, M.; Abdelaal, A.; Amarpal; Behery, A.; Abdel-Aal, A.-B.; Samy, M.-T.; Dhama, K. Radiographic Specification of Skeletal Maturation in Donkeys: Defining the Ossification Time of Donkey Growth Plates for Preventing Irreparable Damage. Asian J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 2016, 11, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Saez, M.; Escobar, A.; Tadich, T.A. Morphological characteristics and most frequent health constraints of urban draught horses attending a free healthcare programme in the south of Chile: A retrospective study (1997–2009). Livest. Res. Rural Dev. 2013, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Bukhari, S.; McElligott, A.G.; Parkes, R.S.V. Quantifying the Impact of Mounted Load Carrying on Equids: A Review. Animals 2021, 11, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukhari, S.; Rosanowski, S.M.; McElligott, A.G.; Parkes, R.S.V. Welfare Concerns for Mounted Load Carrying by Working Donkeys in Pakistan. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 886020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhanang, U.; Pradhanang, S.; Sthapit, A.; Krakauer, N.; Jha, A.; Lakhankar, T. National Livestock Policy of Nepal: Needs and Opportunities. Agriculture 2015, 5, 103–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreevy, P.; McLean, A. Equitation Science, 1st ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.; Goodwin, D.; Heleski, C.; Randle, H.; Waran, N. Is there evidence of learned helplessness in horses? J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2008, 11, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preshaw, L.; Kirton, R.; Randle, H. Application of learning theory in horse rescues in England and Wales. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2017, 190, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, T.; Kubasiewicz, L.M.; Nye, C.; Thapa, S.; Chamberlain, N.; Burden, F. The welfare and access to veterinary health services of mules working the mountain trails in Gorkha region, Nepal. Austral J. Vet. Sci. 2022, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Rousing, T.; Bonde, M.; Sørensen, J.T. Aggregating Welfare Indicators into an Operational Welfare Assessment System: A Bottom-up Approach. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. A—Anim. Sci. 2010, 51, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, C.; Pinzke, S.; Herlin, A.; Keeling, L.J. Human-animal interactions and safety during dairy cattle handling--Comparing moving cows to milking and hoof trimming. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 2131–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, D.; Weary, D.M.; Pajor, E.A.; Milligan, B.N. A Scientific Conception of Animal Welfare that Reflects Ethical Concerns. Anim. Welf. 1997, 6, 187–205. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson, S.; Carson, S.; Fisher, M. Saddle fitting, recognising an ill-fitting saddle and the consequences of an ill-fitting saddle to horse and rider. Equine Vet. Educ. 2015, 27, 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigham, A.W. Genetics of human origin and evolution: High-altitude adaptations. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2016, 41, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penaloza, D.; Arias-Stella, J. The heart and pulmonary circulation at high altitudes: Healthy highlanders and chronic mountain sickness. Circulation 2007, 115, 1132–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, P.; Sharma, A.; Sodhi, M.; Thakur, K.; Bharti, V.K.; Kumar, P.; Giri, A.; Kalia, S.; Swami, S.K.; Mukesh, M. Overexpression of genes associated with hypoxia in cattle adapted to Trans Himalayan region of Ladakh. Cell Biol. Int. 2018, 42, 1141–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinkler, S.H.; Lecca, P.; Weil, A.; Couetil, L.L. Cardiopulmonary parameters in field anesthetized working equids at high altitude in the Peruvian Andes. In Proceedings of the WEVA, Verona, Italy, 3–5 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, H.M.; Cogger, E.A.; Miltenberger, T.L.; Koch, A.K.; Bray, R.E.; Wickler, S.J. Metabolic and osmoregulatory function at low and high (3800 m) altitude. Equine Vet. J. Suppl. 2002, 34, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UN. Climate Change and Social Inequality; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yap, N. Disaster Management, Developing Country Communities and Climate Change: The Role of ICTs; University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Panthi, J.; Dahal, P.; Shrestha, M.; Aryal, S.; Krakauer, N.; Pradhanang, S.; Lakhankar, T.; Jha, A.; Sharma, M.; Karki, R. Spatial and Temporal Variability of Rainfall in the Gandaki River Basin of Nepal Himalaya. Climate 2015, 3, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, S.; El Harrad, A.; Bell, S.; Setchell, J.M. Decolonizing Primate Conservation Practice: A Case Study from North Morocco. Int. J. Primatol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Watson, T.; Kubasiewicz, L.M.; Nye, C.; Thapa, S.; Norris, S.L.; Chamberlain, N.; Burden, F.A. “Not All Who Wander Are Lost”: The Life Transitions and Associated Welfare of Pack Mules Walking the Trails in the Mountainous Gorkha Region, Nepal. Animals 2022, 12, 3152. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12223152

Watson T, Kubasiewicz LM, Nye C, Thapa S, Norris SL, Chamberlain N, Burden FA. “Not All Who Wander Are Lost”: The Life Transitions and Associated Welfare of Pack Mules Walking the Trails in the Mountainous Gorkha Region, Nepal. Animals. 2022; 12(22):3152. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12223152

Chicago/Turabian StyleWatson, Tamlin, Laura M. Kubasiewicz, Caroline Nye, Sajana Thapa, Stuart L. Norris, Natasha Chamberlain, and Faith A. Burden. 2022. "“Not All Who Wander Are Lost”: The Life Transitions and Associated Welfare of Pack Mules Walking the Trails in the Mountainous Gorkha Region, Nepal" Animals 12, no. 22: 3152. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12223152

APA StyleWatson, T., Kubasiewicz, L. M., Nye, C., Thapa, S., Norris, S. L., Chamberlain, N., & Burden, F. A. (2022). “Not All Who Wander Are Lost”: The Life Transitions and Associated Welfare of Pack Mules Walking the Trails in the Mountainous Gorkha Region, Nepal. Animals, 12(22), 3152. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12223152