Confounding Rules Can Hinder Conservation: Disparities in Law Regulation on Domestic and International Parrot Trade within and among Neotropical Countries

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Systematic Legislation Search

2.2. International Legal Trade

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

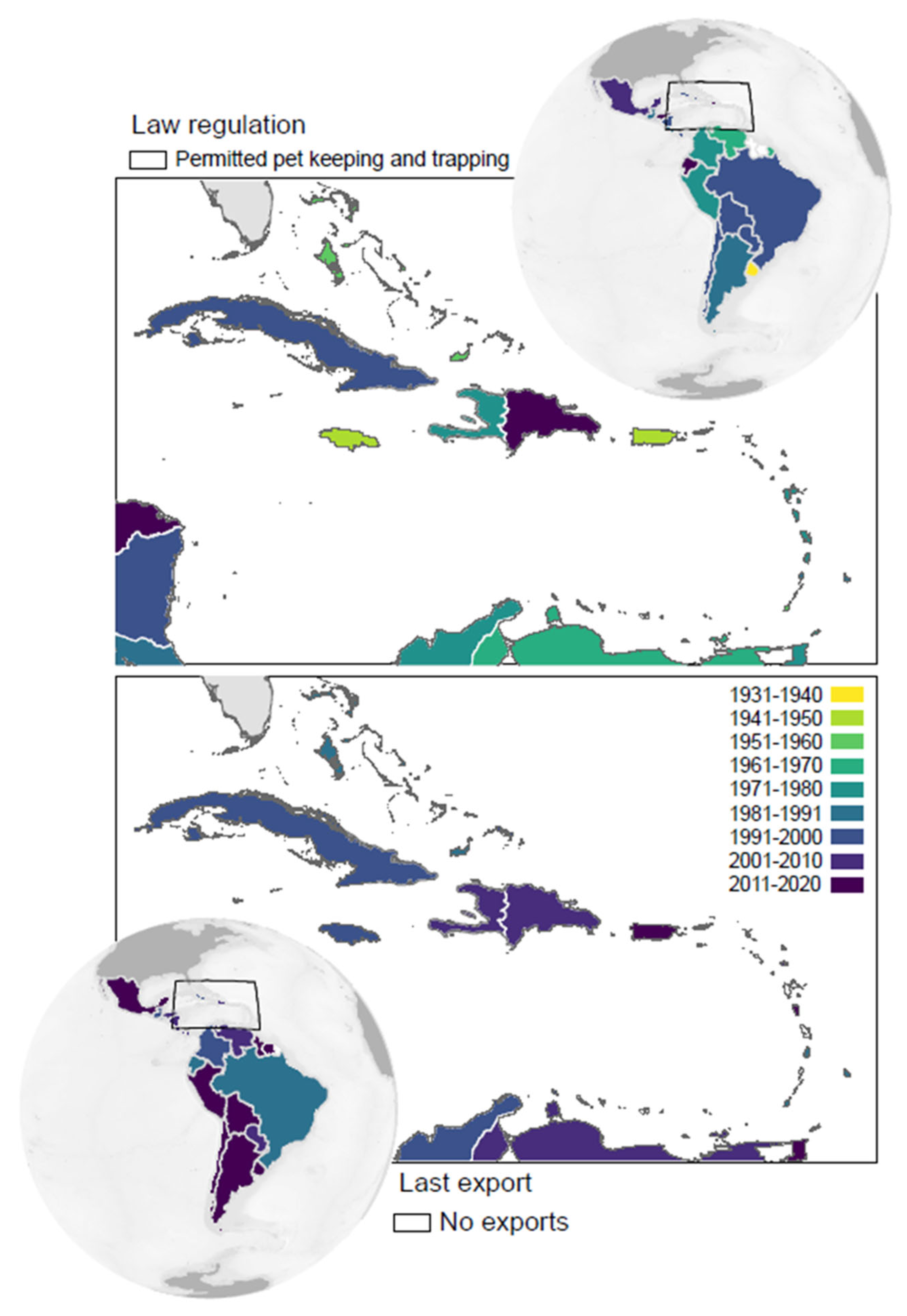

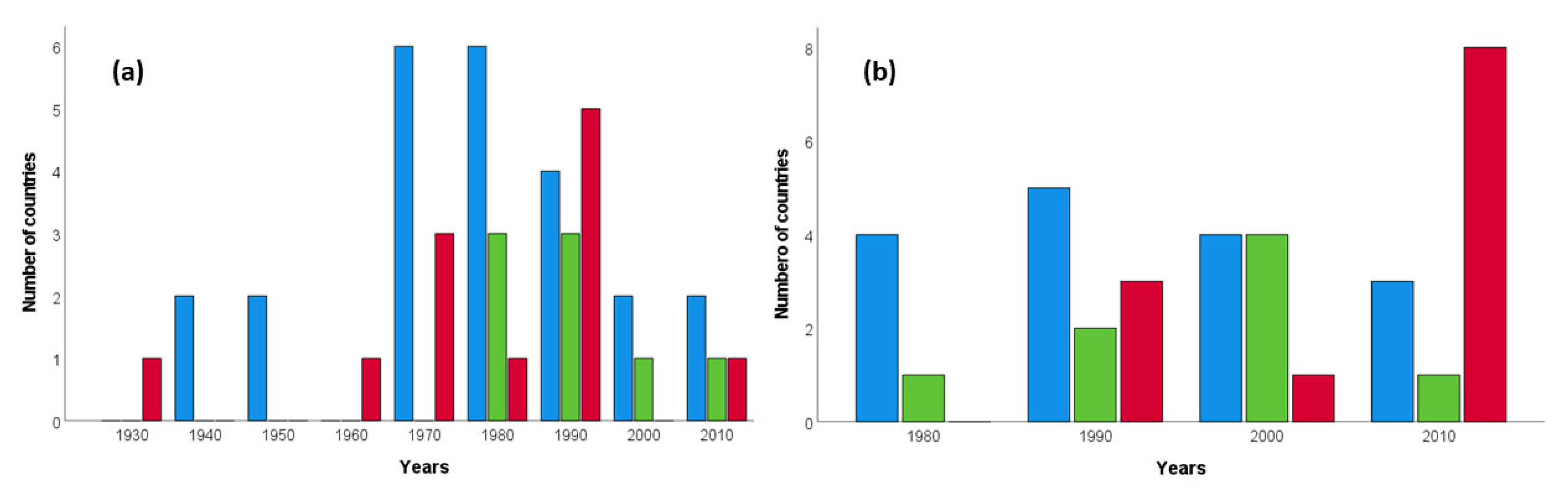

3.1. Domestic Parrot Trapping and Trade

3.2. International Parrot Trade

3.3. Temporal Mismatches between Legal Domestic and International Parrot Trade

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Young, H.S.; McCauley, D.J.; Galetti, M.; Dirzo, R. Patterns, Causes, and Consequences of Anthropocene Defaunation. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2016, 47, 333–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosen, G.E.; Smith, K.F. Summarizing the evidence on the international trade in illegal wildlife. EcoHealth 2010, 7, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelps, J.; Webb, E.L.; Bickford, D.; Nijman, V.; Sodhi, N.S. Boosting CITES. Science 2010, 330, 1752–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nijman, V. An overview of international wildlife trade from Southeast Asia. Biodivers. Conserv. 2010, 19, 1101–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chan, D.T.C.; Poon, E.S.K.; Wong, A.T.C.; Sin, S.Y.W. Global trade in parrots–Influential factors of trade and implications for conservation. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2021, 30, e01784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijman, V.; Morcatty, T.Q.; Feddema, K.; Campera, M.; Nekaris, K.A.I. Disentangling the Legal and Illegal Wildlife Trade–Insights from Indonesian Wildlife Market Surveys. Animals 2022, 12, 628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challender, D.W.; Brockington, D.; Hinsley, A.; Hoffmann, M.; Kolby, J.E.; Massé, F.; Natusch, D.J.; Oldfield, T.E.; Outhwaite, W.; ’t Sas-Rolfes, M.; et al. Mischaracterizing wildlife trade and its impacts may mislead policy processes. Conserv. Lett. 2022, 15, e12832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, E.R.; Baker, S.E.; Macdonald, D.W. Global trade in exotic pets 2006–2012. Conserv. Biol. 2014, 28, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furnell, S. Strengthening CITES Processes for Reviewing Trade in Captive-Bred Specimens and Preventing mis-Declaration and Laundering: A Review of Trade in Southeast Asian Parrot Species; TRAFFIC: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cardador, L.; Tella, J.L.; Anadón, J.D.; Abellán, P.; Carrete, M. The European trade ban on wild birds reduced invasion risks. Conserv. Lett. 2019, 12, e12631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atoussi, S.; Bergin, D.; Razkallah, I.; Nijman, V.; Bara, M.; Bouslama, Z.; Houhamdi, M. The trade in the endangered African Grey Parrot Psittacus erithacus and the Timneh Parrot Psittacus timneh in Algeria. Ostrich 2020, 91, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.; D’Cruze, N.; Senni, C.; Martin, R.O. Inferring patterns of wildlife trade through monitoring social media: Shifting dynamics of trade in wild-sourced African Grey parrots following major regulatory changes. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2022, 33, e01964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Mercado, A.; Ferrer-Paris, J.R.; Rodríguez, J.P.; Tella, L.J. A Literature Synthesis of Actions to Tackle Illegal Parrot Trade. Diversity 2021, 13, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forshaw, J.M. Parrots of the World: Helm Field Guides; A & C Black Publishers Ltd.: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, T.F.; Toft, C.A.; Enkerlin-Hoeflich, E.; Gonzalez-Elizondo, J.; Albornoz, M.; Rodríguez-Ferraro, A.; Rojas-Suárez, F.; Sanz, V.; Trujillo, A.; Beissinger, S.R.; et al. Nest poaching in Neotropical parrots. Conserv. Biol. 2001, 15, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, S.F.; Schneider, J.L.; Herrera, M. Organized crime or crime that is organized? The parrot trade in the neotropics. Trends Organ. Crime 2016, 19, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-von Halle, B. Bird’s-Eye View: Lessons from 50 Years of Bird Trade Regulation & Conservation in AMAZON Countries; TRAFFIC: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Berkunsky, I.; Quillfeldt, P.; Brightsmith, D.J.; Abbud, M.C.; Aguilar, J.M.R.E.; Alemán-Zelaya, U.; Aramburú, R.M.; Arce Arias, A.; Balas McNab, R.; Balsby, T.J.S.; et al. Current threats faced by Neotropical parrot populations. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 214, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herrera, M.; Hennessey, B. Quantifying the illegal parrot trade in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, with emphasis on threatened species. Bird Conserv. Int. 2007, 17, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gastañaga, M.; MacLeod, R.; Hennessey, B.; Núñez, J.U.; Puse, E.; Arrascue, A.; Hoyos, J.; Chambi, W.M.; Vasquez, J.; Engblom, G. A study of the parrot trade in Peru and the potential importance of internal trade for threatened species. Bird Conserv. Int. 2011, 21, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daut, E.F.; Brightsmith, D.J.; Mendoza, A.P.; Puhakka, L.; Peterson, M.J. Illegal domestic bird trade and the role of export quotas in Peru. J. Nat. Conserv. 2015, 27, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, Á.; Romero-Vidal, P.; Hiraldo, F.; Tella, J.L. Cities may save some threatened species but not their ecological functions. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Vidal, P.; Hiraldo, F.; Rosseto, F.; Blanco, G.; Carrete, M.; Tella, J.L. Opportunistic or Non-Random Wildlife Crime? Attractiveness rather than abundance in the wild leads to selective parrot poaching. Diversity 2020, 12, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Mercado, A.; Blanco, O.; Sucre-Smith, B.; Briceño-Linares, J.M.; Peláez, C.; Rodríguez, J.P. Using peoples’ perceptions to improve conservation programs: The yellow-shouldered amazon in Venezuela. Diversity 2020, 12, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, R.; Solis-Ponce, I.; Jones, M.; Pilgrim, M.; Marsden, S. Parrot ownership and capture in coastal Ecuador: Developing a trapping pressure index. Diversity 2021, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J.A. Harvesting, local trade, and conservation of parrots in the Northeastern Peruvian Amazon. Biol. Conserv. 2003, 114, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanee, N.; Mendoza, A.P.; Shanee, S. Diagnostic overview of the illegal trade in primates and law enforcement in Peru. Am. J. Primatol. 2017, 79, e22516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capriles, J.M.; Santoro, C.M.; George, R.J.; Bedregal, E.F.; Kennett, D.J.; Kistler, L.; Rothhammer, F. Pre-Columbian transregional captive rearing of Amazonian parrots in the Atacama Desert. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2020020118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.; Reino, L.; Schindler, S.; Strubbe, D.; Vall-llosera, M.; Bastos Araújo, M.; Capinha, C.; Carrete, M.; Mazzoni, S.; Monteiro, M.; et al. Trends in legal and illegal trade of wild birds: A global assessment based on expert knowledge. Biodiv. Conserv. 2019, 28, 3343–3369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, C.; Chapman, C.A.; Sengupta, R. Spatial patterns of illegal resource extraction in Kibale National Park, Uganda. Environ. Conserv. 2011, 39, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huxley, C. Endangered Species Threatened Convention: The Past, Present and Future of CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora; Routledge: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, J.L. Sold into Extinction: The Global Trade in Endangered Species; Praeger: Westport, CT, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pires, S.F.; Moreto, W.D. Preventing Wildlife Crimes: Solutions That Can Overcome the ‘Tragedy of the Commons’. Eur. J. Crim. Policy Res. 2011, 17, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, A.A.; Catherina, R.; Frye, H.; Shelley, L. Illicit wildlife trade, wet markets, and COVID-19: Preventing future pandemics. World Med. Health Policy 2020, 12, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.O.; Frankham, G.J.; Bond, L.; Stuart, B.H.; Johnson, R.N.; Ueland, M. An overview of risk investment in the transnational illegal wildlife trade from stakeholder perspectives. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Forensic Sci. 2021, 3, e1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Vidal, P. The Overlooked Dimensions of Domestic Parrot Poaching in the Neotropics. PhD’s Dissertation, Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Seville, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovich, J. Parrots, Precaution and Project Elé: Management in the Face of Multiple Uncertainties. Biodiversity and the Precautionary Principle; EarthScan: London, UK, 2012; pp. 173–188. [Google Scholar]

- Gilardi, J.D. To ban or not to ban: A reply to Jorge Rabinovich. Oryx 2006, 40, 263–264. [Google Scholar]

- Falcón, W.; Tremblay, R.L. From the cage to the wild: Introductions of Psittaciformes to Puerto Rico. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cantú, J.C.; Sánchez, M.E.; Grosselet, M.; Silve, J. The Illegal Parrot Trade in Mexico: A Comprehensive Assessment; Defenders of Wildlife: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; p. 121. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, J.; Hiraldo, F.; Romero, M.A.; Tella, J.L. When does agriculture enter into conflict with wildlife? A global assessment of parrot-agriculture conflicts and their conservation effects. Divers. Distrib. 2021, 27, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daut, E.F.; Brightsmith, D.J.; Peterson, M.J. Role of non-governmental organizations in combating illegal wildlife–pet trade in Peru. J. Nat. Conserv. 2015, 24, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briceño-Linares, J.M.; Rodríguez, J.P.; Rodríguez-Clark, K.M.; Rojas-Suárez, F.; Millán, P.A.; Vittori, E.G.; Carrasco-Muñoz, M. Adapting to changing poaching intensity of yellow-shouldered parrot (Amazona barbadensis) nestlings in Margarita Island, Venezuela. Biol. Conserv. 2011, 144, 1188–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodrati, A.; Cockle, K.; Areta, J.I.; Capuzzi, G.; Fariña, R. El Maracaná Lomo Rojo (Primolius maracana) en Argentina:¿ de plaga a la extinción en 50 años? Hornero 2006, 21, 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Muccio, C. Estudio de Caso Sobre el Tráfico Ilegal del Loro Nuca Amarilla en Guatemala; WCS/DOS-INL: Guatemala City, Guatemala, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tella, J.L.; Hiraldo, F. Illegal and legal parrot trade shows a long-term, cross-cultural preference for the most attractive species increasing their risk of extinction. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107546. [Google Scholar]

| Country | Native Parrots | Year | Law | Last Year Export | No. of Individuals | No. of Species | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anguilla (UK) | no | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Antigua and Barbuda | no | 2015 | Environmental protection and management act No. 11. | 2004 | 13 | 6 | E |

| Argentina | yes | 1981 | Ley 22.421 | 2017 | 1,397,420 | 27 | B |

| Aruba | yes | 1995 | Natuurbeschermingsverordening. | 1993 | 2 | 1 | E |

| Bahamas | yes | 1952 | Act Nº 52 | 1988 | 2 | 2 | E |

| Barbados | no | 1985 | Wild Birds Protection Act. Ordinance No. 27. | 1989 | 138 | 5 | E |

| Belize | yes | 1981 | Wildlife Protection Act No. 4. | 1994 | 19 | 6 | B |

| Bermuda | no | 2006 | Endangered Animals and Plants Act | - | - | - | - |

| Bolivia | yes | 1999 | Ley 1333 | 2012 | 167,581 | 46 | B |

| Brazil | yes | 1998 | LEI Nº 9.605 | 1990 | 331 | 8 | B |

| British Virgin Islands | no | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Cayman Islands | yes | 1989 | National Conservation Law | 1994 | 6 | 5 | E |

| Chile | yes | 1998 | ley 19.473 | 2018 | 4755 | 5 | B |

| Colombia | yes | 1977 | Resolucion 0787 | 1992 | 574 | 8 | B |

| Costa Rica | yes | 1983 | Ley Nº 6.919—Ley de conservación de la fauna silvestre; substituted by Ley 7317. | 2004 | 7343 | 11 | B |

| Cuba | yes | 1997 | Ley del Medio Ambiente, Ley 81 | 1999 | 94 | 7 | B |

| Dominica | yes | 1976 | Forestry and Wildlife Act. | 2013 | 12 | 6 | B |

| Dominican Republic | yes | 2015 | Ley Sectorial sobre Biodiversidad, No. 333-15. G. O. No. 10822 | 2004 | 506 | 9 | B |

| Ecuador | yes | 2014 | Codigo Integral Penal Art. 247 | 1990 | 16,226 | 25 | B |

| El Salvador | yes | 1994 | Ley de conservación de vida silvestre. Decreto Legislativo D Nº: 844. | 1989 | 4801 | 8 | B |

| Falkland Islands | no | 1999 | Conservation of Wildlife and Nature Ordinance No. 10 | - | - | - | - |

| French Guiana | yes | 1967 | Loi 5197 | - | - | - | - |

| Grenada | no | 1957 | Birds and Other Wild Life Protection Ordinance No. 26 | 1989 | 96 | 4 | E |

| Guadeloupe | no | 1977 | Loi Nº 76-629. Decret Nº 77-1295. | - | - | - | - |

| Guatemala | yes | 1989 | Ley de Areas Protegidas | 1998 | 16,591 | 12 | B |

| Guyana | yes | Allowed | Wildlife Conservation and Management Bill 2016 | 2019 | 469,940 | 34 | B |

| Haiti | yes | 1971 | Decret organisant la surveillance et la Police de la chasse | 2003 | 7 | 2 | N |

| Honduras | yes | 2016 | Ley de protección y bienestar animal. Decreto 115-2015. | 2009 | 130,376 | 33 | B |

| Jamaica | yes | 1945 | Wild life Protection Act. | 1996 | 382 | 3 | B |

| Martinique | no | 1977 | Loi Nº 76-629. Decret Nº 77-1295. | - | - | - | - |

| Mexico | yes | 2000 | Ley General de Vida Silvestre | 2011 | 15,071 | 20 | B |

| Montserrat | no | 1996 | Forestry, Wildlife, National Parks and Protected Areas Act. Act 3. | - | - | - | - |

| Netherlands Antilles | yes | - | - | 2004 | 60 | 7 | B |

| Nicaragua | yes | 1998 | Ley General del Medio Ambiente y Los Recursos Naturales. Ley No. 217. Decreto No. 8-98. | 2007 | 86,246 | 18 | B |

| Panama | yes | 1995 | Ley de Vida Silvestre de Panama. LeyNo. 24. | 2006 | 358 | 18 | B |

| Paraguay | yes | 1992 | Ley nº 96 de Vida Silvestre | 2010 | 19,635 | 12 | N |

| Peru | yes | 1975 | Decreto Ley Nº 21147—Ley forestal y de fauna silvestre. | 2017 | 362,881 | 28 | B |

| Puerto Rico | yes | 1946 | Commonwealth regulations (EYNF) | 2012 | 3 | 2 | E |

| Saint Kitts and Nevis | no | 1987 | National Conservation and Environment Protection Act No. 5 | - | - | - | - |

| Saint Lucia | yes | 1980 | Wildlife Protection Act No. 9 | 1989 | 50 | 1 | N |

| Saint Martin (FR) | no | 1977 | Loi Nº 76-629. Decret Nº 77-1295. | - | - | - | - |

| Saint Vicent and the Grenadines | yes | 1987 | Wildlife Protection Act | - | - | - | - |

| Saint-Barthélemy (FR) | no | 1977 | Loi Nº 76-629. Decret Nº 77-1295. | - | - | - | - |

| Sint Maarten (NL) | no | 2003 | Nature Conservation Ordinance St. Marteen. AB2003, No. 25 | - | - | - | - |

| Suriname | yes | Allowed | - | 2019 | 243,330 | 28 | B |

| Trinidad and Tobago | yes | 1980 | Conservation of Wild Life Regulations. Conservation of Wildlife Act 16 | 2017 | 214 | 6 | B |

| Turks and Caicos Islands | no | - | - | 1992 | 1 | 1 | E |

| United States Virgin Islands | no | 1990 | Species Act of 1990 | - | - | - | - |

| Uruguay | yes | 1935 | Ley Nº 9.481—Normas sobre protección de la fauna indígena. | 2017 | 1,054,406 | 11 | B |

| Venezuela | yes | 1970 | Gaceta Oficial 29.289 | 2007 | 3324 | 9 | B |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Romero-Vidal, P.; Carrete, M.; Hiraldo, F.; Blanco, G.; Tella, J.L. Confounding Rules Can Hinder Conservation: Disparities in Law Regulation on Domestic and International Parrot Trade within and among Neotropical Countries. Animals 2022, 12, 1244. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12101244

Romero-Vidal P, Carrete M, Hiraldo F, Blanco G, Tella JL. Confounding Rules Can Hinder Conservation: Disparities in Law Regulation on Domestic and International Parrot Trade within and among Neotropical Countries. Animals. 2022; 12(10):1244. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12101244

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomero-Vidal, Pedro, Martina Carrete, Fernando Hiraldo, Guillermo Blanco, and José L. Tella. 2022. "Confounding Rules Can Hinder Conservation: Disparities in Law Regulation on Domestic and International Parrot Trade within and among Neotropical Countries" Animals 12, no. 10: 1244. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12101244

APA StyleRomero-Vidal, P., Carrete, M., Hiraldo, F., Blanco, G., & Tella, J. L. (2022). Confounding Rules Can Hinder Conservation: Disparities in Law Regulation on Domestic and International Parrot Trade within and among Neotropical Countries. Animals, 12(10), 1244. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12101244