Donkey Ownership Provides a Range of Income Benefits to the Livelihoods of Rural Households in Northern Ghana

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

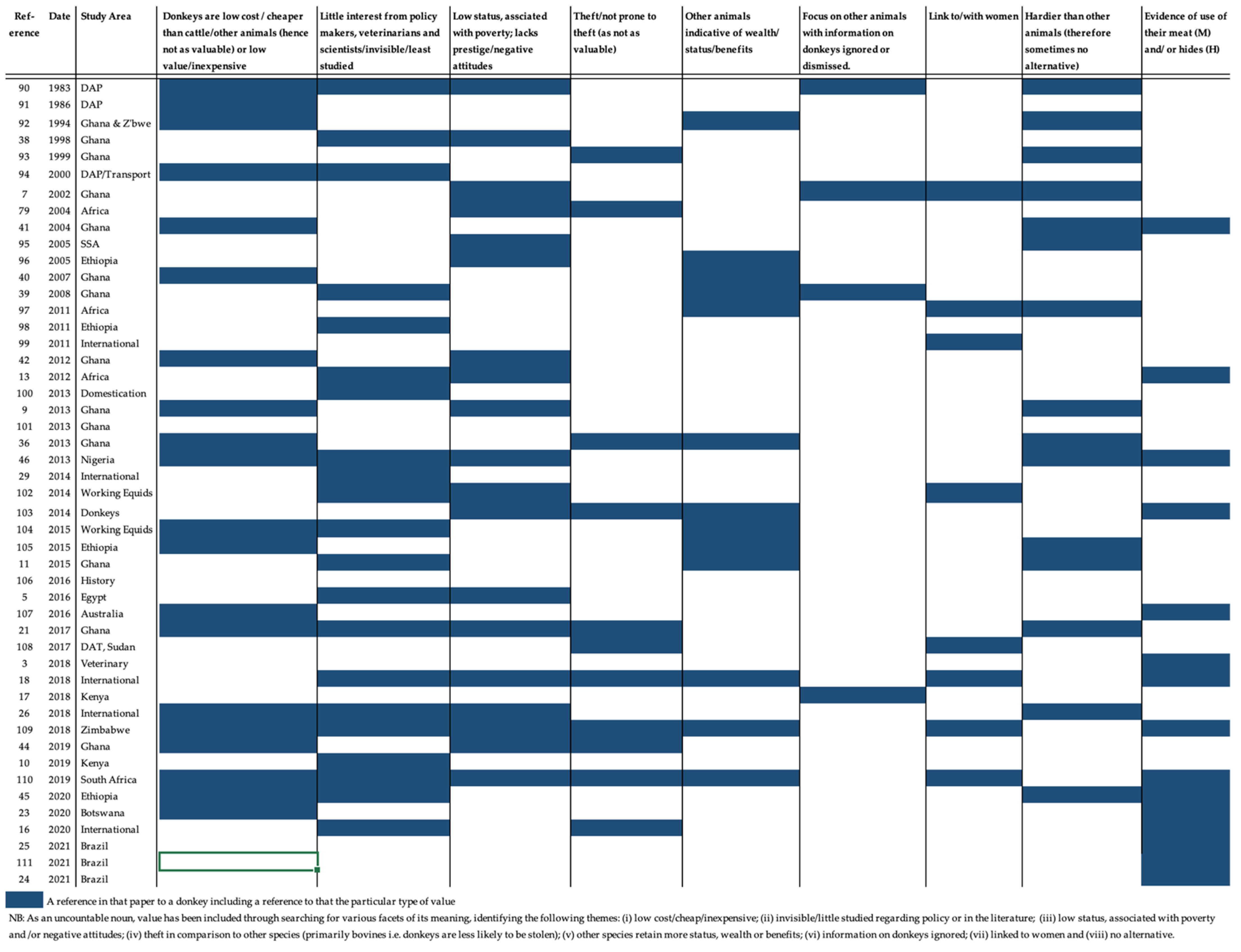

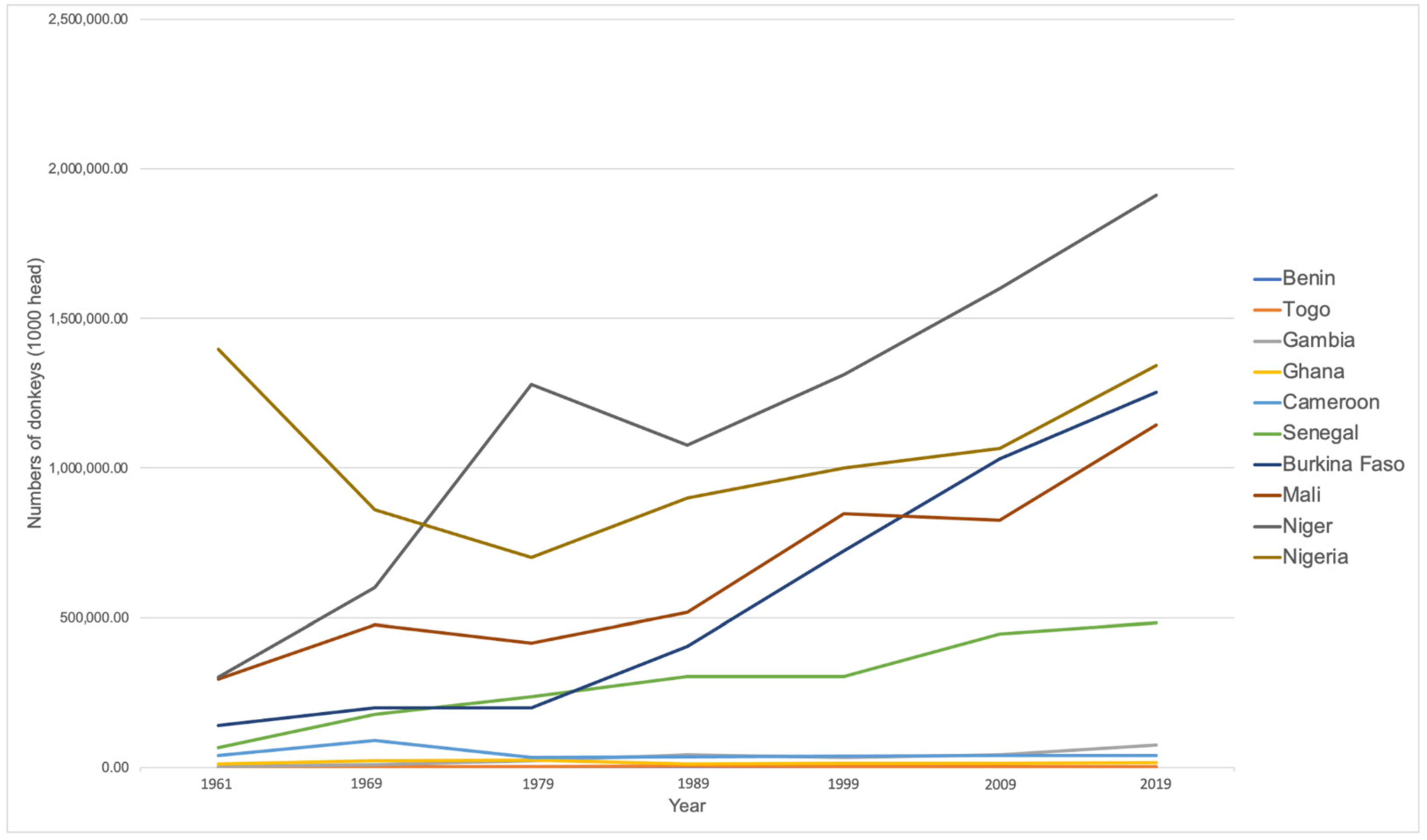

1. Introduction

“Anytime I don’t have money, I use the donkey to work and earn money at the end of the day. I can make at least 50.00 GH¢ (£6.48) and I can use that money to buy a female goat and it will reproduce”Kahiau, (RID27M67).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preliminary Considerations

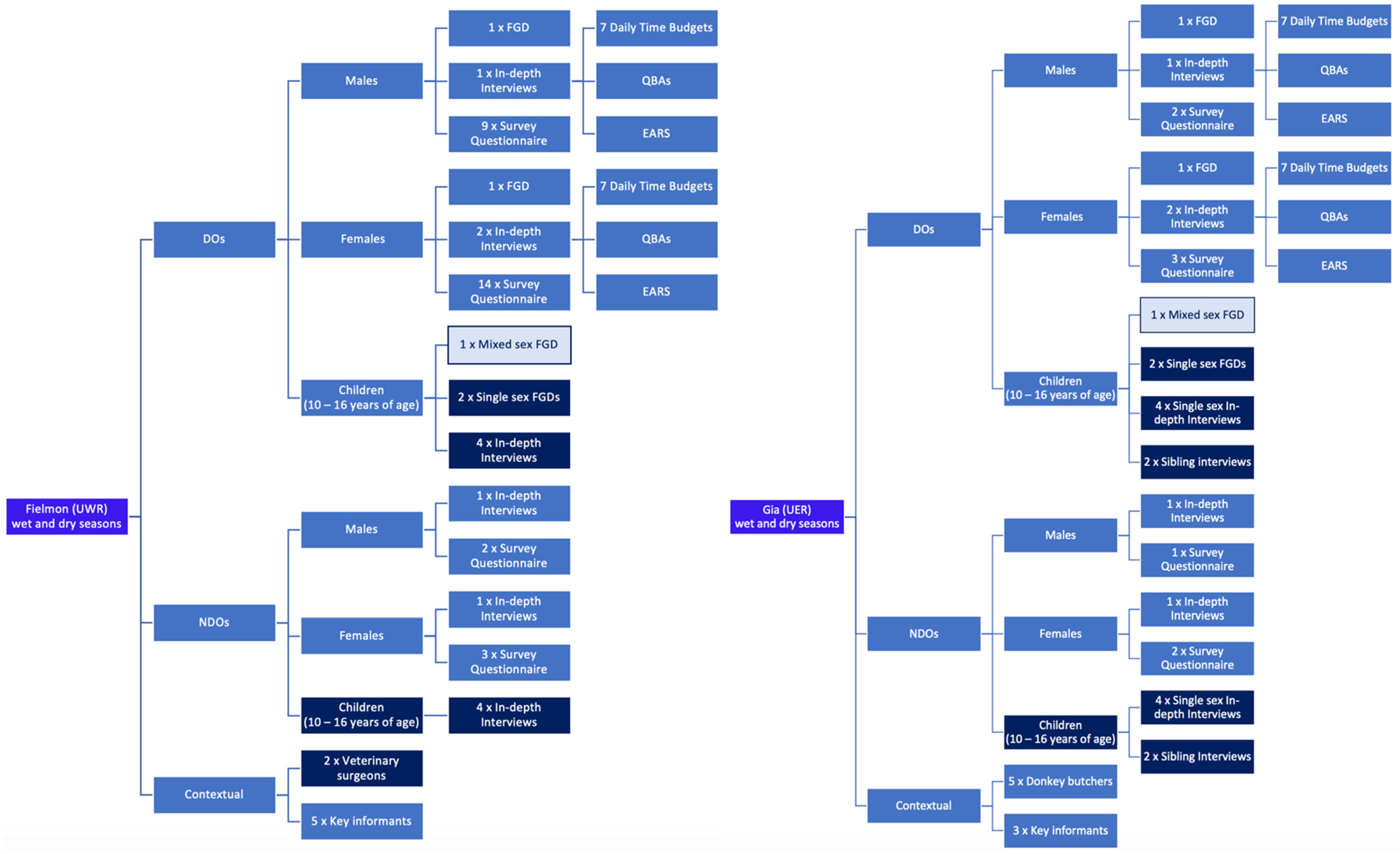

2.2. Data Collection and Study Location

2.3. Ethical Considerations

2.4. Ethics Approval and Sampling

2.5. Adult Research Instruments

2.6. Children’s Research Instruments

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. A Market for Hiring out Donkeys and Carts

3.2. Six Different Income Benefits from Donkey Ownership

3.2.1. Domestic Use of Donkeys for Non-Monetary Income Benefits (Cashless Indirect)

3.2.2. Direct Income Generation Utilising Donkeys (Direct)

The Role of Children in Direct Income Generation Utilising Donkeys

3.2.3. Speculative Sales as a Means of Generating Income from a Donkey and Cart (Indirect)

3.2.4. Speculative Collection as a Means of Generating Income from a Donkey and Cart (Indirect)

3.2.5. Generating Income through the Sale of Donkey Intestine Soup (Indirect)

3.2.6. Donkey Ownership Generates Income Benefits through the Saving of Time (Cashless Indirect)

3.3. Income Generated from the Use of Donkeys

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementaly Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Çakırlar, C.; Chahoud, J.; Berthon, R.; Pilaar Birch, S. Archaeozoology of the Near East XII. In Proceedings of the 12th International Symposium of the ICAZ Archaeozoology of Southwest Asia and Adjacent Areas Working Group, Groningen Institute of Archaeology, The Netherlands, Barkhuis, 14–15 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dezzutto, D.; Barbero, R.; Valle, E.; Giribaldi, M.; Raspa, F.; Biasato, I.; Cavallarin, L.; Bergagna, S.; McLean, A.; Gennero, M.S. Observations of the hematological, hematochemical, and electrophoretic parameters in lactat-ing donkeys (Equus asinus). J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2018, 65, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.A.W.Q.; Weng, Q. China: Will the donkey become the next pangolin? Equine Vet. J. 2018, 50, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burden, F.; Thiemann, A. Donkeys are different. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2015, 35, 376–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.B.; El Sayed, M.A.; Matoock, M.Y.; Fouad, M.A.; Heleski, C.R. A welfare assessment scoring system for working equids—A method for identifying at risk populations and for monitoring progress of welfare en-hancement strategies (trialled in Egypt). Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 176, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, J.C. Animal traction and transport in the 21st century: Getting the priorities right. Veter J. 2010, 186, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, G. Intermediate means of transport: A review paper with special reference to Ghana [monograph]. Technical Report. University of Durham, Durham. Available online: https://dro.dur.ac.uk/14145/ (accessed on 7 March 2018).

- Starkey, P.; Fernando, P. Women, Transport Energy and Donkeys: Some Implications for Development Workers. EN-ERGIA News Issue 2.2, May. Available online: https://www.ssatp.org/sites/ssatp/files/publications/HTML/Gender-RG/Source%20%20documents/Issue%20and%20Strategy%20Papers/G&T%20Rationale/ISGT19%20Women%20Transport%20Energy%20and%20Donkeys%20Starkey.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Braimah, M.M.; Abdul-Rahaman, I.; Oppong-Sekyere, D. Donkey-Cart Transport, a Source of Livelihood for Farmers in the Kassena Nankana Municipality in Upper East Region of Ghana. J. Biol. Agric. Healthc. 2013, 3, 127–136. [Google Scholar]

- Mwasame, D.B.; Otieno, D.J.; Nyang’ang’a, H. Quantifying the contribution of donkeys to household live-lihoods; Evidence from Kiambu county, Kenya. In Proceedings of the 6th African Conference of Agricultural Economists, Abuja, Nigeria, 23–26 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Avornyo, F.K.; Teye, G.A.; Bukari, D.; Salifu, S. Contribution of donkeys to household food security: A case study in the Bawku Municipality of the Upper East Region of Ghana. Ghana J. Sci. Technol. Dev. 2015, 3, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Admassu, B.; Shiferaw, Y. Donkeys, Horses and Mules–Their Contribution to People’s Livelihoods in Ethiopia. The Brooke, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Available online: https://www.thebrooke.org/sites/default/files/Advocacy-and-policy/Ethiopia-livelihoods-2020-01.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Blench, R. May Wild asses and donkeys in Africa: Interdisciplinary evidence for their biogeography, history and current use. In Proceedings of the 9th Donkey Conference, School of Oriental and African Studies, London, UK, 9 May 2012; pp. 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Valle, E.; Pozzo, L.; Giribaldi, M.; Bergero, D.; Gennero, M.S.; Dezzutto, D.; McLean, A.; Borreani, G.; Coppa, M.; Cavallarin, L. Effect of farming system on donkey milk composition. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 98, 2801–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawthorn, D.M.; Hoffman, L.C. Controversial cuisine: A global account of the demand, supply and ac-ceptance of “unconventional” and “exotic” meats. Meat Sci. 2016, 120, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.; Pfuderer, S. The Potential for New Donkey Farming Systems to Supply the Growing Demand for Hides. Animals 2020, 10, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dumas, S.E.; Maranga, A.; Mbullo, P.; Collins, S.; Wekesa, P.; Onono, M.; Young, S.L. ”Men are in front at eating time, but not when it comes to rearing the chicken”: Unpacking the gendered benefits and costs of livestock ownership in Kenya. Food Nutr. Bull. 2018, 39, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goulder, J.R. Modern Development Studies as a Resource for Understanding Working Animal use in Later Human Prehistory: The Example of 4th-3rd Millennium BC Mesopotamia. Ph.D. Thesis, University College London, London, UK.

- Geiger, M.; Hovorka, A.J. Animal performativity: Exploring the lives of donkeys in Botswana. Environ. Plan. D: Soc. Space 2015, 33, 1098–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, M.; Whay, R. Summary on the Socio-economic Value of Working Donkeys in Central Ethiopia. Final Research Report; The Donkey Sanctuary and Bristol University: Bristol, UK.

- Braimah, M.M.; Akampirige, A.O.M. Donkeys Transport, Source of Livelihoods, Food Security and Tra-ditional Knowledge, the Myths about Donkeys Usage: A Case of the Bolgatanga Municipality Ghana. Int. J. Curr. Res. Acad. Rev. 2017, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bennett, R.; Pfuderer, S. Demand for Donkey Hides and Implications for Global Donkey Populations. In Proceedings of the 93rd Annual Conference of the Agricultural Economics Society, Warwick University, Coventry, UK, 15–17 April 2020; Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/agsaesc19/289683.htm (accessed on 11 April 2021).

- Matlhola, D.M.; Chen, R. Telecoupling of the Trade of Donkey-Hides between Botswana and China: Challenges and Opportunities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tatemoto, P.; Lima, Y.F.; Santurtun, E.; Reeves, E.K.; Raw, Z. Donkey skin trade: Is it sustainable to slaughter donkeys for their skin? Braz. J. Vet. Res. Anim. Sci. 2021, 58, e174252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skippen, L.; Collier, J.; Kithuka, J.M. The donkey skin trade: A growing global problem. Braz. J. Vet. Res. Anim. Sci. 2021, 58, e175262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, A.K.; González, F.J.N. Can Scientists Influence Donkey Welfare? Historical Perspective and a Contemporary View. J. Equine Veter Sci. 2018, 65, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- FAO. FAOSTAT. Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home (accessed on 26 December 2019).

- Zeder, M.A. Domestication and early agriculture in the Mediterranean Basin: Origins, diffusion, and impact. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 11597–11604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Dijk, L.; Duguma, B.E.; Hernández Gil, M.; Marcoppido, G.; Ochieng, F.; Schlechter, P.; Starkey, P.; Wanga, C.; Zanella, A. Role, Impact and Welfare of Working (Traction and Transport) Animals; FAO Animal Production and Health Report eng no. 5; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- The Donkey Sanctuary, Under the Skin: The Emerging Trade in Donkey Skins and its Implications for Donkey Welfare and Livelihoods. Available online: https://www.thedonkeysanctuary.org.uk/sites/uk/files/2017-11/under_the_skin_report.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2018).

- Köhle, N. Feasting on Donkey Skin in Golley. In China Story Yearbook 2017: Prosperity; Golley, J., Jaivin, L., Eds.; ANU Publications: Canberra, Australia, 2018; pp. 176–181. [Google Scholar]

- CGTN. China Cuts Tariff on Donkey Hides. CGTN. Business. 31 December 2017. Available online: https://news.cgtn.com/news/3067444d35637a6333566d54/index.html (accessed on 15 August 2019).

- Xinhua News Agency. Shortage of Donkey Skin Breeds TCM Fakes. China Daily. 28 January 2016. Available online: http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2016-01/28/content_23287841.htm (accessed on 5 September 2017).

- BBC News. “Why are donkeys facing their ‘biggest ever crisis’?”. 7 October 2017. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-41524710 (accessed on 14 October 2017).

- Starkey, P.; Starkey, M. Regional and World Trends in Donkey Populations. In Donkeys, People and Development. A Resource Book in the Animal Traction Network for Eastern and Southern Africa (ATNESA); ACP-EU Technical Centre for Agriculture and Rural Cooperation: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2004; p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- Houssou, N.; Kolavalli, S.; Bobobee, E.; Owusu, V. Animal Traction in Ghana; Ghana Strategy Support Program Working Paper; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Geest, K.V.D. ‘We’re managing!’: Climate Change and Livelihood Vulnerability in Northwest Ghana. African Studies Centre Research Report, Type book-monograph. Available online: https://scholarlypublications.universiteitleiden.nl/access/item%3A3143942/view (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Canacoo, E.; Avornyo, F. Daytime activities of donkeys at range in the coastal savanna of Ghana. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1998, 60, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madama, E.; Naazie, A.; Adogla-Bessa, T.; Adjorlolo, L. Use of donkeys and cattle as draught animals in the Northern and Upper East and Volta Regions of Ghana. Draught Anim. News 2008, 46, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bobobee, E.Y. Performance Analysis of Draught Animal-Implement System to Improve Productivity and Welfare. Ph.D. Thesis, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden.

- Canacoo, E. Utilisation of donkeys in southern Ghana. In Donkeys, People and Development. A Resource Book in the Animal Traction Network for Eastern and Southern Africa (ATNESA); Fielding, D., Starkey, P., Eds.; ACP-EU Technical Centre for Agriculture and Rural Cooperation: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bellwood-Howard, I. Donkeys and bicycles: Capital interactions facilitating timely compost application in Northern Ghana. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2012, 10, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, A.J.; Van der Geest, K.; Obeng, F.; Yaro, J.A. Local perceptions of development and change in Northern Ghana. In Rural development in Northern Ghana; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Tuaruka, L.; Agbolosu, A.A. Assessing Donkey Production and Management in Bunkpurugu/Yunyoo District in the Northern Region of Ghana. J. Husb. Dairy Sci. 2019, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, M.; Hockenhull, J.; Buller, H.; Tefera Engida, G.; Mulugeta, G.; Burden, F.; Whay, B. Understanding the Attitudes of Communities to the Social, Economic, and Cultural Importance of Working Donkeys in Rural, Peri-urban, and Urban Areas of Ethiopia. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, M.R.; Steenstra, F.A.; Udo, H.M.J. Benefits of donkeys in rural and urban areas in northwest Nigeria. J. Agric. Res. 2013, 8, 6202–6212. [Google Scholar]

- Mileage Obtained from Google Maps. Available online: https://bit.ly/3kPedPv and https://bit.ly/3kPYP5c (accessed on 6 March 2021).

- The Donkey Sanctuary, Under the Skin: Update on the Global Crisis for Donkeys and the People Who Depend on Them. Available online: https://www.thedonkeysanctuary.org.uk/sites/uk/files/2019-11/underthe-skin-report-revised-2019.pdf (accessed on 7 December 2019).

- von Maxwell, S. Killing Donkeys. 2018. Available online: https://www.dandc.eu/de/article/too-many-donkeys-are-slaughtered-ghana-order-export-their-meat-and-skins (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism, 2019. The Donkey Slaughter Capital of West Africa. Available online: https://oxpeckers.org/2019/05/donkey-slaughter-capital-of-west-africa/ (accessed on 1 September 2018).

- Lawton, M.P.; Brody, E.M.; Médecin, U. Instrumental activities of daily living (IADL). Essential Activities of Daily Living (EADL) have been adapted and developed from a gerontological concept in the Minority world: Activities of Daily Living or ADLs. These basic self-care tasks: Eating; bathing; dressing; toileting; grooming and mobility are used to assess functionality of older people and can be used to decide the levels of care packages needed to suit current abilities. One of the first references to ADLs dates back Powell Lawton & Brody. Gerontologist 1969, 9, 179. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, E. Choosing a methodology: Philosophical underpinning. Pract. Res. Higher Educ. 2013, 7, 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghana-Net.com. Nalerigu named capital of newly created North East Region. 12 February 2019. Ghana Signed into Law a Further Six Regions in April 2019, from the Original The Regions in Which This Research Was Un-dertaken Remain Unchanged, although all Regional Data in this Paper Pertains to the Original 10 Regions, in Place Prior to 2019. Available online: http://ghana-net.com/ghana-district-news/category/regions-of-ghana (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Raw, Z.; Rodrigues, J.B.; Rickards, K.; Ryding, J.; Norris, S.L.; Judge, A.; Kubasiewicz, L.M.; Watson, T.L.; Little, H.; Hart, B.; et al. Equid assessment, research and scoping (EARS): The development and implemen-tation of a new equid welfare assessment and monitoring tool. Animals 2020, 10, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Minero, M.; Dalla Costa, E.; Dai, F.; Murray, L.A.M.; Canali, E.; Wemelsfelder, F. Use of Qualitative Behaviour Assessment as an indicator of welfare in donkeys. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2016, 174, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Molyneux, C.; Peshu, N.; Marsh, K. Understanding of informed consent in a low-income setting: Three case studies from the Kenyan coast. Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 59, 2547–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindana, P.O.; Kass, N.; Akweongo, P. The informed consent process in a rural African setting: A case study of the Kassena-Nankana district of Northern Ghana. IRB: Ethic Hum. Res. 2006, 28, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Barker, J.; Weller, S. Is it fun? Developing children centred research methods. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2003, 23, 33–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crivello, G.; Camfield, L.; Woodhead, M. How Can Children Tell Us About Their Wellbeing? Exploring the Potential of Participatory Research Approaches within Young Lives. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 90, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beazley, H.; Bessell, S.; Ennew, J.; Waterson, R. The right to be properly researched: Research with children in a messy, real world. Child. Geogr. 2009, 7, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, Convention New York, UNICEF. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention/convention-text (accessed on 21 August 2018).

- Brady, L.M.; Graham, B. Social Research with Children and Young People: A Practical Guide; Policy Press: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rodik, P.; Primorak, J. To Use or Not to Use: Computer-Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software. Available online: https://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/2221 (accessed on 9 October 2021).

- Shonfelder, W. CAQDAS and Qualitative Syllogism Logic—NVivo 8 and MAXQDA 10 Compared. Available online: https://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1514/3134 (accessed on 9 October 2021).

- John, W.S.; Johnson, P. The Pros and Cons of Data Analysis Software for Qualitative Research. J. Nurs. Sch. 2000, 32, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamawe, F.C. The Implication of Using NVivo Software in Qualitative Data Analysis: Evidence-Based Reflec-tions. J. Med Assoc. Malawi 2015, 27, 13–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maher, C.; Hadfield, M.; Hutchings, M.; De Eyto, A. Ensuring Rigor in Qualitative Data Analysis. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2018, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners; SAGE: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; SAGE: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Evers, J.C. Elaborating on thick analysis: About thoroughness and creativity in qualitative analysis. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moor, T. Why do Smallholder Farmers in Northern-Ghana Choose to Plough by hoe, with Bullocks or with Tractors? Master’s Thesis, Wageningen University and Research Centre, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, G.; Hampshire, K.; Dunn, C.; Hall, R.; Levesley, M.; Burton, K.; Robson, S.; Abane, A.; Blell, M.; Panther, J. Health impacts of pedestrian head-loading: A review of the evidence with particular reference to women and children in sub-Saharan Africa. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 88, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duncan, B.A. Women in Agriculture in Ghana; Friedrich Ebert Foundation: Accra, Ghana, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Louw, Q.A.; Morris, L.D.; Grimmer-Somers, K. The Prevalence of low back pain in Africa: A systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2007, 8, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geere, J.-A.L.; Hunter, P.R.; Jagals, P. Domestic water carrying and its implications for health: A review and mixed methods pilot study in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Environ. Heal. 2010, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoy, D.; March, L.; Woolf, A.; Blyth, F.; Brooks, P.; Smith, E.; Vos, T.; Barendregt, J.; Blore, J.; Murray, C.; et al. The global burden of neck pain: Estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2014, 73, 1309–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geere, J.-A.; Bartram, J.; Bates, L.; Danquah, L.; Evans, B.; Fisher, M.B.; Groce, N.; Majuru, B.; Mokoena, M.M.; Mukhola, M.S.; et al. Carrying water may be a major contributor to disability from musculoskeletal disorders in low income countries: A cross-sectional survey in South Africa, Ghana and Vietnam. J. Glob. Health 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, P.; Starkey, P. Donkeys and Development: Socio-Economic Aspects of Donkey Use in Africa. In Donkeys, People and Development. A Resource Book in the Animal Traction Network for Eastern and Southern Africa (ATNESA); Fielding, D., Starkey, P., Eds.; ACP-EU Technical Centre for Agriculture and Rural Cooperation: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bank of Ghana, 2021. Statistics and Reports Office. The Ghanaian Cedi: The Unit of Currency of Ghana, Which is Divided into 100 Pesewas. Available online: https://www.bog.gov.gh/bank-notes-coins/evolution-of-currency-in-ghana/ (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Moser, C.O. Gender planning in the third world: Meeting practical and strategic gender needs. World Dev. 1989, 17, 1799–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah, M.; Blay, D.; Damnyag, L.; Dwomoh, F.K.; Pappinen, A.; Luukkanen, O. Dependence on forest resources and tropical deforestation in Ghana. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2007, 11, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anang, B.T.; Akuriba, M.A.; Alerigesane, A. Charcoal production in Gushegu District, Northern Region, Ghana: Lessons for sustainable forest management. Int. of Environ. Sci. 2011, 1, 1944–1953. [Google Scholar]

- Amoah, M.; Cremer, T.; Dadzie, P.K.; Ohene, M.; Marfo, O. Firewood collection and consumption practic-es and barriers to uptake of modern fuels among rural households in Ghana. Int. Forestry Rev. 2019, 21, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrant, G.; Pesando, L.M.; Nowacka, K. Unpaid Care Work: The Missing Link in the Analysis of Gender Gaps in Labour Outcomes; OECD Development Center: Boulogne Billancourt, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bigler, C.; Amacker, M.; Ingabire, C.; Birachi, E. A view of the transformation of Rwanda's highland through the lens of gender: A mixed-method study about unequal dependents on a mountain system and their well-being. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 69, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanello, G.; Srinivasan, C.S.; Nkegbe, P. Piloting the use of accelerometry devices to capture energy ex-penditure in agricultural and rural livelihoods: Protocols and findings from northern Ghana. Develop. Eng. 2017, 2, 114–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilahi, N. The Intra-Household Allocation of Time and Tasks: What have We Learnt from the Empirical Literature? Development Research Group/Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Network; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA; Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.452.2177&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 21 May 2021).

- Gender, Time Use, and Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, N.S. Draught animal power. Ind. Int. Q. 1983, 10, 309–320. [Google Scholar]

- Falvey, J.L. An Introduction to Working Animals; MPW: Melbourne, Australia, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Doran, J. Transportation by women, and their access to animal-drawn carts in Zimbabwe. In Improving Animal Traction Technology; Mwenya, E., Stares, J., Starkey, P., Eds.; CTA: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1994; pp. 272–279. [Google Scholar]

- Bobobee, E.Y. Role of draft animal power in Ghanaian agriculture. In Conservation Tillage with Animal Traction; ATNESA: Harare, Zimbabwe, 1999; pp. 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Mahapa, S.M. Carting in the Northern Province: Structural and geographical change. Dev. South. Afr. 2000, 17, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.G.; Pearson, R.A. A Review of the Factors Affecting the Survival of Donkeys in Semi-arid Regions of Sub-Saharan Africa. Trop. Anim. Heal. Prod. 2005, 37, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tesfaye, A.; Curran, M.M. A Longitudinal Survey of Market Donkeys in Ethiopia. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2005, 37, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, F.; Weissbrod, L. Domestication processes and morphological change: Through the lens of the donkey and African pastoralism. Curr. Anthropol. 2011, 52, S397–S413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnke, R.H.; Metaferia, F. The Contribution of Livestock to the Ethiopian Economy—Part II. IGAD LPI Working Paper 02. 2005. Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/bitstream/handle/10568/24968/IGAD_LPI_WP_02-10.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 11 September 2021).

- Sims, B.; Röttger, A.; Mkomwa, S. Hire Services by Farmers for Farmers; FAO Diversification Booklet; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, B.; Marshall, F.; Beja-Pereira, A.; Mulligan, C. Donkey domestication. Afr. Archaeol. Rev. 2013, 30, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braimah, M.M.; Abdul-Rahaman, I.; Oppong-Sekyere, D. Factors that impedes draught animal technol-ogy in Kasenna Nankana municipality in the Upper East Region, Ghana. Int. J. Innov. Agric. Biol. Res. 2013, 1, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Valette, D. Invisible Helpers. Women’s Views on the Contributions of Working Donkeys, Horses and Mules to their Lives; Brooke: London, UK, 2014; p. 20143204172. [Google Scholar]

- Blakeway, S. The Multi-dimensional Donkey in Landscapes of Donkey-Human Interaction. Relations 2014, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Valette, D. Invisible Workers. The Economic Contributions of Working Donkeys, Horses and Mules to Livelihoods; Brooke: London, UK , 2015; p. 20153416319. [Google Scholar]

- Gina, T.G.; Tadesse, B.A. The role of working animals toward livelihoods and food security in selected districts of Fafan Zone, Somali Region, Ethiopia. Adv. Life Sci. Technol. 2015, 33, 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, V. Asses. In Mason’s World Encyclopedia of Livestock Breeds and Breeding; Porter, V., Alderson, L., Hall, S.J., Sponenberg, D.P., Eds.; CABI: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Primary Industry and Resources (Australia). Donkey Business: Potential of the donkey industry in the Northern Territory. 2016. Available online: https://industry.nt.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/373642/donkey-business-discussion-paper.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Makki, E.K.; Eltayeb, F.E.; Badri, O.A. Situation of Women Farmers Using Draught Animal Technology (DAT) in Elfashir, North Darfur State. J. Innov. Res. 2017, 5, 687–693. [Google Scholar]

- Mutizhe, E. The feasibility of donkey skin trade in Zimbabwe as a strategy to tap into the emerging donkey export market. Master’s Thesis, Bindura University of Science Education, Bindura, Zimbabwe, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Binda, K. A Donkey’s Worth in South Africa: Domestic Laborer or Export Product; Socioeconomic impacts of China’s skin trade on South African donkey owners. Master’s Thesis, Charles University in Prague, Prague, The Czech Republic, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gameiro, M.B.P.; Rezende, V.T.; Zanella, A.J. Brazilian donkey slaughter and exports. J. Vet. Res. Anim. Sci. 2002, 58, e174697. [Google Scholar]

| Study Site | No. of Respondents | Girls | Boys | Age Range (years) | Mean Age (years) | Family Owns 1 Donkey | Family Owns 2 Donkey | Family Owns 3 Donkey | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fielmon | Mixed sex FGD | December 2018 | 12 | 3 | 9 | 10–16 | 11.58 | 7 | 4 | 1 |

| Girls only | June 2019 | 8 | 8 | 12–15 | 13 | 4 | 4 | |||

| Boys only | June 2019 | 8 | 8 | 12–15 | 13.2 | 8 | ||||

| Gia | Mixed sex FGD | December 2018 | 11 | 4 | 7 | 10–16 | 12.81 | 0 | 8 | 3 |

| Girls only | June 2019 | 7 | 7 | 10–13 | 12 | 2 | 4 | 1 | ||

| Boys only | June 2019 | 8 | 8 | 10–14 | 13 | 2 | 4 | 2 | ||

| Method of Income Generation | Description | Potential Earnings Per Hire (GH¢) | Illustrative Participant Quotation | RID | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Domestic (Cashless Indirect) | No income generating activities per se. | Not applicable, but saves costs. | Still contributes to household income, through not having to hire in transportation and ploughing assistance - information provided by Jalia (DO). Also saves time, itemised separately under 6. | 25 |

| 2. | Direct Hire (Direct) | Hire directly for an EADL. | 10.00–20.00 GH¢ (£1.40–2.80). | Approximate weekly income from hiring out her donkey, costs quoted by Maiara (DO). | 28 |

| 3. | Speculative Selling (Indirect) | Collect a load of wood with no one in mind to sell it to, to sell 'on spec' to anyone who needs wood, for any purpose. | “Costs 5 GH¢ (£0.70) twice per week to hire a donkey to cart firewood back from the bush.” | Costs to hire a donkey and cart to collect firewood she has cut and collected in the bush, quoted by Selma (NDO). The only alternative is for her to carry it home on her head. | 38 |

| 4. | Speculative Collection (Indirect) | Collect firewood to sell “commercially” to specific petty traders. Rather than collecting wood to be sold to any person who needs it, a particular target audience is kept in mind by the DO when collecting wood. | 50.00 GH¢ (£6.95) per day. | Anytime I don’t have money, I use the donkey to work and earn money at the end of the day. I can make at least 50.00 GH¢ and I can use that money to buy a female goat and it will reproduce” Kahiau (DO). | 27 |

| 5. | Donkey Intestine Soup (Indirect) | Selling donkey intestine soup. | Unknown. | An option available only in Gia. Sharpur (a DO) reported women collecting donkey intestines at the slaughterhouses, making soup from them and then selling the soup, as “a business opportunity.” | 21 |

| 6. | Freeing Time (Cashless Indirect) | Saving time, which can be converted into money, through paid employment. | "We usually pay GH¢ 15 (£2.10) per person on [a] daily basis." | Costs provided by an NDO Kali (NDO 41) who reported: “We pay people to plough, sow, and even weed on our farm," to the benefit of Esosa, a DO (29) who advised that owning a donkey "saves me time to engage in a day job like sowing on someone’s farm for money.” | 41 and 29 |

| Unique ID | Study Site | Gender | Respon-dent * | Key EADLs Using Their Donkey | Income Generating Methods Used | Donkey’s Contri-bution to HH Income | Time Their Donkey(s) Saves Her/Him |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 29 | Gia | Female | Esosa | Income generation was the second key reason why she owns a donkey as it is the main source of her income. | Domestic; Direct Hire; Speculative Selling; Speculative Collection and Freeing Time. | 60% | “I can go to the market to sell my vegetables after using the donkey to carry out carting work/job”. |

| 28 | Gia | Female | Maiara | Brews pito to sell and does hire out her donkeys for income. | Domestic; Direct Hire; Speculative Selling; Speculative Collection and Freeing Time. | 40% | 2 h a day |

| 24 | Fielmon | Female | Abi | Domestic use, saved time and hiring out for income through her children. Currently, only her boys are old enough to assist in hiring donkey out: her girls are too young. | Domestic; Direct Hire; Speculative Selling; Speculative Collection and Freeing Time. | 40% | 6 h a day |

| 25 | Fielmon | Female | Jalia | Domestic use and saved time only: currently, no children old enough to help with hiring their donkey out. | Domestic; Freeing Time. | 30% | <1 h a day (6 h per week) |

| 27 | Gia | Male | Kahiau | Domestic, farming and gardening use, plus conscious breeding of females to minimise re-purchase costs. | Domestic; Direct Hire; Speculative Selling; Speculative Collection and Freeing Time. | ~50% | “Much time is saved for my household to perform other works. The saved time I use it to work on my garden.” |

| 26 | Fielmon | Male | Kaif | Domestic and farming chores and occasionally rents out his donkey and cart to carry firewood for a fee. | Domestic; Direct Hire; Speculative Selling; Speculative Collection and Freeing Time. | 40% | Saves men 5 h per week; women 5 h per week; children 10 h per week |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maggs, H.C.; Ainslie, A.; Bennett, R.M. Donkey Ownership Provides a Range of Income Benefits to the Livelihoods of Rural Households in Northern Ghana. Animals 2021, 11, 3154. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11113154

Maggs HC, Ainslie A, Bennett RM. Donkey Ownership Provides a Range of Income Benefits to the Livelihoods of Rural Households in Northern Ghana. Animals. 2021; 11(11):3154. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11113154

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaggs, Heather C., Andrew Ainslie, and Richard M. Bennett. 2021. "Donkey Ownership Provides a Range of Income Benefits to the Livelihoods of Rural Households in Northern Ghana" Animals 11, no. 11: 3154. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11113154

APA StyleMaggs, H. C., Ainslie, A., & Bennett, R. M. (2021). Donkey Ownership Provides a Range of Income Benefits to the Livelihoods of Rural Households in Northern Ghana. Animals, 11(11), 3154. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11113154