Feed Preference Response of Weaner Bull Calves to Bacillus amyloliquefaciens H57 Probiotic and Associated Volatile Organic Compounds in High Concentrate Feed Pellets

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Pellets, Animals, and Experimental Design

2.2. Chemical Analysis

2.3. Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS)

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

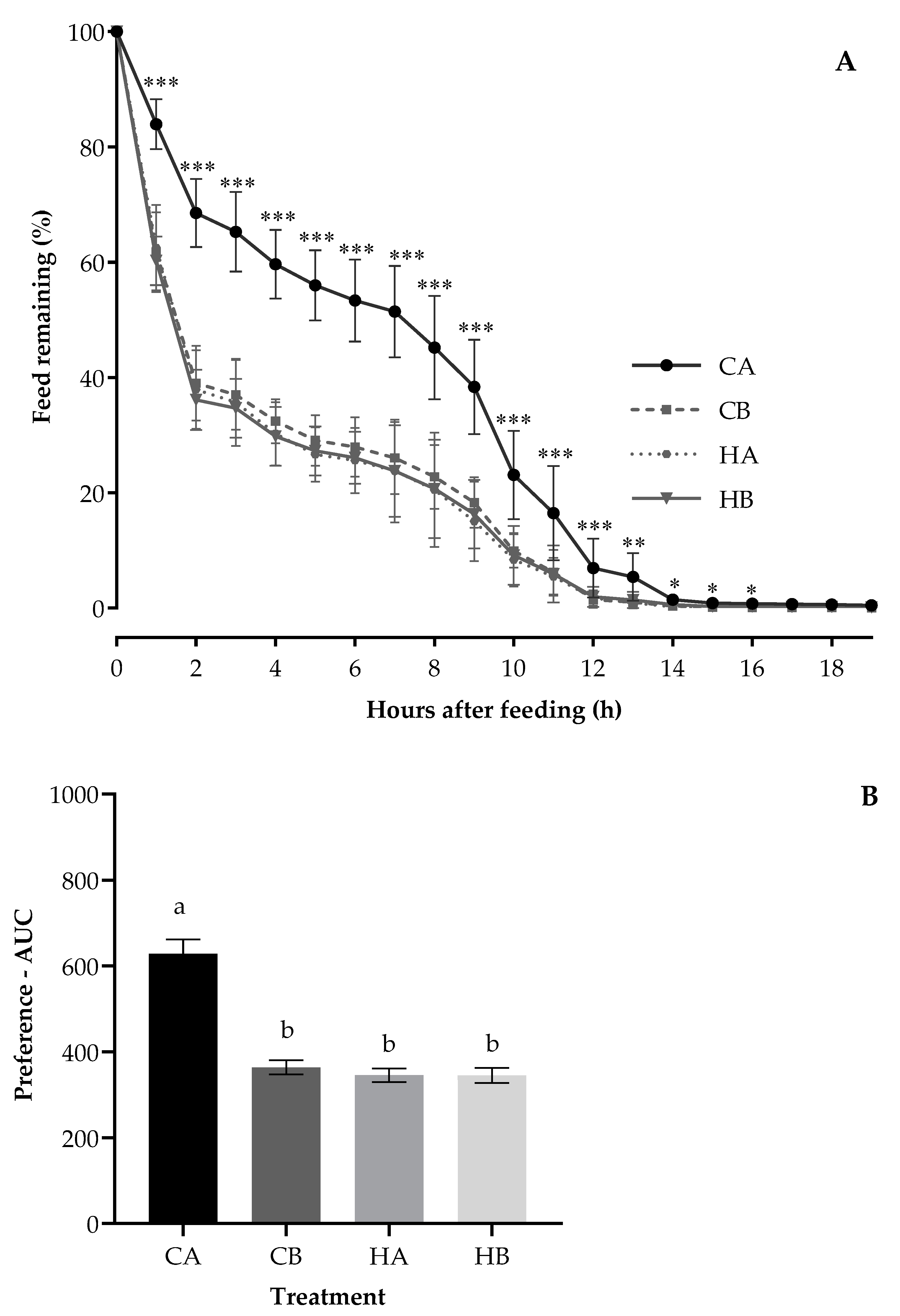

3.1. Preference Test

3.2. Volatile Organic Compound Profiles in the Pellet Treatments Offered in the Preference Test

3.3. Relationship between Preference and VOCs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Provenza, F.D.; Scott, C.B.; Phy, T.S.; Lynch, J.J. Preference of sheep for foods varying in flavors and nutrients. J. Anim. Sci. 1996, 74, 2355–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Provenza, F.D. Postingestive feedback as an elementary determinant of food preference and intake in ruminants. J. Range Manag. 1995, 48, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favreau-Peigné, A.; Baumont, R.; Ginane, C. Food sensory characteristics: Their unconsidered roles in the feeding behaviour of domestic ruminants. Animal 2013, 7, 806–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedelkov, K.; Harper, M.T.; Melgar, A.; Chen, X.; Räisänen, S.; Martins, C.M.M.R.; Faugeron, J.; Wall, E.H.; Hristov, A.N. Acceptance of flavored concentrate premixes by young ruminants following a short-term exposure. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spörndly, E.; Åsberg, T. Eating rate and preference of different concentrate components for cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 2188–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalba, J.J.; Bach, A.; Ipharraguerre, I.R. Feeding behavior and performance of lambs are influenced by flavor diversity. J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 89, 2571–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, G.W.; Boer, E.S.; Boundy, C.A.P. The influence of odour and taste on the food preferences and food intake of sheep. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1980, 31, 571–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estell, R.E.; Fredrickson, E.L.; Tellez, M.R.; Havstad, K.M.; Shupe, W.L.; Anderson, D.M.; Remmenga, M.D. Effects of volatile compounds on consumption of alfalfa pellets by sheep. J. Anim. Sci. 1998, 76, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pain, S.J. Identifying Nutritive, Physical and Volatile Characteristics of Oaten and Lucerne Hay that Affect the Short-Term Feeding Preferences of Lactating Holstein Friesian Cows and Thoroughbred Horses. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rapisarda, T.; Mereu, A.; Cannas, A.; Belvedere, G.; Licitra, G.; Carpino, S. Volatile organic compounds and palatability of concentrates fed to lambs and ewes. Small Rumin. Res. 2012, 103, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennerman, K.K.; Al-Maliki, H.S.; Lee, S.; Bennett, J.W. Fungal volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and the genus Aspergillus. In New and Future Developments in Microbial Biotechnology and Bioengineering; Gupta, V.K., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 95–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciorowski, K.G.; Herrera, P.; Jones, F.T.; Pillai, S.D.; Ricke, S.C. Effects on poultry and livestock of feed contamination with bacteria and fungi. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2007, 133, 109–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, A.; Giuberti, G.; Frisvad, J.C.; Bertuzzi, T.; Nielsen, K.F. Review on mycotoxin issues in ruminants: Occurrence in forages, effects of mycotoxin ingestion on health status and animal performance and practical strategies to counteract their negative effects. Toxins 2015, 7, 3057–3111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.; Dart, P. Testing Hay Treated with Mould-Inhibiting, Biocontrol Inoculum: Microbial Inoculant for Hay; Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation: Kingston, Australian Capital Territory, Australia, 2005; pp. 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Le, O.T.; Schofield, B.; Dart, P.J.; Callaghan, M.J.; Lisle, A.T.; Ouwerkerk, D.; Klieve, A.V.; McNeill, D.M. Production responses of reproducing ewes to a by-product-based diet inoculated with the probiotic Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain H57. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2016, 57, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, O.T.; Dart, P.J.; Callaghan, M.J.; Klieve, A.V.; McNeill, D.M. Preference of weaner calves for pellets is improved by inclusion of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens spores as an ingredient. In Proceedings of the 31st Biennial Conference of the Australian Society for animal welfare-meat consumer needs and increasing productivity, Adelaide, SA, Australia, 4–7 July 2016; Australian Society of Animal Production: Orange East, NSW, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield, B.J. Microbial Community Structure and Functionality in Ruminants Fed the Probiotic Bacillus amyloliquefaciens H57. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Queensland, Birsbane, QLD, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Harrigan, W.F.; McCance, M.E. The Microbiological Examination of Foods. In Laboratory Methods in Microbiology; Academic Press: London, UK, 1966; pp. 106–133. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis; Association of Official Analytical Chemists: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizsan, S.J.; Randby, A.T. The effect of fermentation quality on the voluntary intake of grass silage by growing cattle fed silage as the sole feed. J. Anim. Sci. 2007, 85, 984–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camo. The Unscrambler X User’s Guide, Version 10.5; Camo Software AS.: Oslo, Norway, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mayland, H.F.; Flath, R.A.; Shewmaker, G.E. Volatiles from fresh and air-dried vegetative tissues of tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea Schreb.): Relationship to cattle preference. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 2204–2210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Raza, W.; Shen, Q.; Huang, Q. Antifungal activity of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens NJN-6 volatile compounds against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 5942–5944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magan, N.; Evans, P. Volatiles as an indicator of fungal activity and differentiation between species, and the potential use of electronic nose technology for early detection of grain spoilage. J. Stored Prod. Res 2000, 36, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morath, S.U.; Hung, R.; Bennett, J.W. Fungal volatile organic compounds: A review with emphasis on their biotechnological potential. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2012, 26, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, S.M.S.; Hassan, W.H.; Shawki, H.M.; El-Lateef Osman, W.A. Study on toxigenic fungi in ruminant feeds under desert conditions with special references to its biological control. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2015, 4, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleurat-Lessard, F. Integrated management of the risks of stored grain spoilage by seedborne fungi and contamination by storage mould mycotoxins—An update. J. Stored Prod. Res 2017, 71, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, J.; Börjesson, T.; Lundstedt, T.; Schnürer, J. Detection and quantification of Ochratoxin A and Deoxynivalenol in barley grains by GC-MS and electronic nose. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2002, 72, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buśko, M.; Stuper, K.; Jeleń, H.; Góral, T.; Chmielewski, J.; Tyrakowska, B.; Perkowski, J. Comparison of volatiles profile and contents of Trichothecenes group b, Ergosterol, and ATP of bread wheat, durum wheat, and triticale grain naturally contaminated by mycobiota. Front. Plant. Sci. 2016, 7, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, J.W.; Inamdar, A.A. Are some fungal volatile organic compounds (VOCs) mycotoxins? Toxins 2015, 7, 3785–3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girotti, J.R.; Malbran, I.; Lori, G.A.; Juárez, M.P. Early detection of toxigenic Fusarium graminearum in wheat. World Mycotoxin J. 2012, 5, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infantino, A.; Aureli, G.; Costa, C.; Taiti, C.; Antonucci, F.; Menesatti, P.; Pallottino, F.; De Felice, S.; D’Egidio, M.G.; Mancuso, S. Potential application of PTR-TOFMS for the detection of deoxynivalenol (DON) in durum wheat. Food Control. 2015, 57, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippolis, V.; Cervellieri, S.; Damascelli, A.; Pascale, M.; Di Gioia, A.; Longobardi, F.; De Girolamo, A. Rapid prediction of deoxynivalenol contamination in wheat bran by MOS-based electronic nose and characterization of the relevant pattern of volatile compounds. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 4955–4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink-Gremmels, J. The role of mycotoxins in the health and performance of dairy cows. Vet. J. 2008, 176, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgavi, D.P.; Boudra, H.; Jouany, J.P.; Graviou, D. Prevention of patulin toxicity on rumen microbial fermentation by SH-containing reducing agents. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 6906–6910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, M.O.; Stern, M.D.; Koski, R.L.; Bach, A.; Murphy, M.J. Effects of patulin on rumen microbial fermentation in continuous culture fermenters. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2002, 97, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, H.D.; Wu, Q.; Blake, C.K. Effects of the Fusarium spp. mycotoxins fusaric acid and deoxynivalenol on the growth of Ruminococcus albus and Methanobrevibacter ruminantium. Can. J. Microbiol. 2000, 46, 692–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, G.L.; Wolf, C.A.; Harsh, S.B. Dairy cattle culling patterns, explanations, and implications. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 2286–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenz, J.R.; Jensen, S.M.; Lombard, J.E.; Wagner, B.A.; Dinsmore, R.P. Herd management practices and their association with bulk tank somatic cell count on United States dairy operations. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 3652–3659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carocho, M.; Ferreira, I.C. A review on antioxidants, prooxidants and related controversy: Natural and synthetic compounds, screening and analysis methodologies and future perspectives. Food. Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 51, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Pellet Treatment 1 | Hay | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | CA | CB | HA | HB | |

| Ingredients (% Dry matter, DM) | |||||

| Sorghum | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | - |

| Millrun | 66.3 | 66.3 | 66.3 | 66.3 | - |

| Full fat soybean | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | - |

| Barley | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 10.0 | - |

| Extruded wheat | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | |

| Molasses | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | - |

| Limestone | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | - |

| Vegetable oil | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | - |

| Salt | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | - |

| Premix 2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | - |

| H57 spores (cfu/g pellet, as fed) | - | - | 3.1 × 106 | 3.1 × 106 | - |

| Chemical component (% DM) | |||||

| DM (%) | 89.5 | 89.3 | 90.5 | 87.8 | 75.0 |

| Crude protein | 16.7 | 16.8 | 16.9 | 17.1 | 7.2 |

| Fat | 5.6 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 0.8 |

| Ash | 7.9 | 7.8 | 7.6 | 7.1 | 13.3 |

| Acid detergent fibre | 9.0 | 11.2 | 11.0 | 11.5 | 46.1 |

| Neutral detergent fibre | 27.7 | 30.5 | 32.6 | 32.6 | 61.4 |

| Starch | 24.3 | 25.6 | 24.3 | 24.1 | 0.4 |

| Calcium | 1.45 | 1.24 | 1.04 | 0.99 | 0.11 |

| Phosphorus | 0.75 | 0.73 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.24 |

| Iron (ppm) | 294 | 256 | 227 | 217 | 369 |

| Zinc (ppm) | 181 | 181 | 159 | 155 | 12 |

| Metabolisable energy (MJ/kg DM) | 12.81 | 12.79 | 12.84 | 12.85 | 7.35 |

| No | Compound Name 1 | Treatment 2 | SEM | p-Value 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA | CB | HA | HB | CA vs. CB vs. HA vs. HB 4 | Probiotic | Temperature | Pro×Tem 5 | |||

| Microbial volatile organic compounds 4 | ||||||||||

| 1 | Butanal, 3-methyl- | 9.7 | 9.6 | 9.2 | 10.2 | 0.24 | 0.04 | 0.94 | 0.14 | 0.12 |

| 2 | Acetic acid | 112 | 93 | 72 | 102 | 5.72 | 0.0002 | 0.03 | 0.40 | 0.005 |

| 3 | Pentanal | 12.9 | 9.6 | 10.8 | 9.1 | 0.32 | <0.0001 | 0.01 | 0.0004 | 0.06 |

| 5 | Pyrazine | 1.7 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 0.04 | <0.0001 | 0.006 | 0.08 | 0.0008 |

| 6 | Propionic acid | 55.0 | 14.6 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 1.17 | <0.0001 | 0.008 | 0.07 | 0.04 |

| 7 | Pyridine | 2.7 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 0.44 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.78 | 0.07 |

| 8 | 1-Pentanol | 6.7 | 3.8 | 4.9 | 2.9 | 0.22 | <0.00 01 | 0.003 | <0.0001 | 0.16 |

| 9 | Hexanal | 26.9 | 17.1 | 19.1 | 14.7 | 0.66 | <0.0001 | 0.0008 | 0.0001 | 0.02 |

| 10 | Pyrazine, methyl- | 14.6 | 12.4 | 11.8 | 12.5 | 0.41 | 0.0002 | 0.08 | 0.29 | 0.07 |

| 12 | Furfural | 20.7 | 15.9 | 15.5 | 17.1 | 0.52 | <0.0001 | 0.008 | 0.02 | 0.0009 |

| 14 | 2-Furanmethanol | 8.6 | 6.3 | 5.0 | 6.4 | 0.26 | <0.0001 | 0.0004 | 0.08 | 0.0004 |

| 15 | 2-Heptanone | 5.1 | 4.0 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 0.23 | 0.006 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| 16 | Heptanal | 2.0 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 0.6 | 0.08 | <0.0001 | 0.62 | 0.12 | 0.85 |

| 17 | Pyrazine, 2,5-dimethyl- | 12.6 | 12.9 | 11.2 | 12.4 | 0.41 | 0.04 | 0.14 | 0.23 | 0.48 |

| 21 | Furan, 2-pentyl- | 16.5 | 10.5 | 10.9 | 9.3 | 0.39 | <0.0001 | 0.0007 | 0.0004 | 0.006 |

| 23 | 1-Octen-3-ol | 2.1 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 0.11 | 0.0001 | 0.03 | 0.005 | 0.08 |

| 24 | Benzaldehyde | 4.6 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 4.0 | 0.10 | <0.0001 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.02 |

| 25 | Pyrazine, 2-ethyl-5-methyl- | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 0.11 | 0.21 | 0.66 | 0.15 | 0.70 |

| 26 | Octanal | 0.8 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.74 | <0.0001 | 0.76 | 0.13 | 0.80 |

| 27 | 2,4-Heptadienal, (E,E)- | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.15 |

| 31 | Nonanal | 5.2 | 3.4 | 3.9 | 3.1 | 0.27 | <0.0001 | 0.03 | 0.005 | 0.14 |

| 32 | 2(3H)-Furanone, 5-ethyldihydro- | 1.7 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 0.05 | <0.0001 | 0.03 | 0.0009 | 0.11 |

| 33 | 2-Nonenal, (E)- | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 0.62 | 0.92 | 0.45 | 0.32 |

| 35 | 2,4-Decadienal, (E,E)- | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.04 | <0.0001 | 0.004 | 0.0009 | 0.007 |

| Non—microbial volatile organic compounds | ||||||||||

| 4 | 2-Propanone, 1-hydroxy- | 38.2 | 31.7 | 22.9 | 33.5 | 1.44 | <0.0001 | 0.001 | 0.14 | 0.0004 |

| 11 | Ethane, 1,2-bis[(4-amino-3-furazanyl)oxy]- | 2.7 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.13 | <0.0001 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.08 |

| 13 | 1-Hexyne, 5-methyl- | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.34 | 0.03 | <0.0001 | 0.25 | 0.43 | 0.86 |

| 18 | Pyrazine, ethyl- | 2.0 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 0.06 | 0.0006 | 0.13 | 0.40 | 0.03 |

| 19 | Cyclotetrasiloxane, octamethyl- | 5.8 | 4.7 | 2.9 | 6.0 | 1.55 | 0.50 | 0.32 | 0.19 | 0.02 |

| 20 | 4-Cyclopentene-1,3-dione | 2.8 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 0.07 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0009 | <0.0001 |

| 22 | 2-Heptenal, (Z)- | 1.9 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 0.09 | <0.0001 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 0.76 |

| 28 | 1,3-Hexadiene, 3-ethyl-2-methyl- | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.04 | <0.0001 | 0.0009 | 0.002 | 0.04 |

| 29 | 1H-Pyrrole-2-carboxaldehyde | 4.9 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 0.14 | <0.0001 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.0004 |

| 30 | 9-Hexadecenoic acid, phenylmethyl ester, (Z)- | 1.9 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 0.06 | <0.0001 | 0.77 | 0.0009 | 0.09 |

| 34 | 2-Decenal, (E)- | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.01 | <0.0001 | 0.002 | 0.0003 | 0.0007 |

| 36 | 4-Hydroxy-2-methylacetophenone | 3.7 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 4.8 | 0.48 | 0.34 | 0.39 | 0.19 | 0.47 |

| 37 | (E)-Tetradec-2-enal | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.10 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.11 | 0.86 |

| 38 | 17-Octadecynoic acid, methyl ester | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.04 | 0.31 | 0.04 | 0.50 | 0.43 |

| 39 | Butylated hydroxytoluene | 0.7 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 0.17 | <0.0001 | 0.004 | 0.001 | 0.02 |

| 40 | 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)- | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.05 | 0.0003 | 0.10 | 0.005 | 0.18 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ngo, T.T.; Bang, N.N.; Dart, P.; Callaghan, M.; Klieve, A.; Hayes, B.; McNeill, D. Feed Preference Response of Weaner Bull Calves to Bacillus amyloliquefaciens H57 Probiotic and Associated Volatile Organic Compounds in High Concentrate Feed Pellets. Animals 2021, 11, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11010051

Ngo TT, Bang NN, Dart P, Callaghan M, Klieve A, Hayes B, McNeill D. Feed Preference Response of Weaner Bull Calves to Bacillus amyloliquefaciens H57 Probiotic and Associated Volatile Organic Compounds in High Concentrate Feed Pellets. Animals. 2021; 11(1):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11010051

Chicago/Turabian StyleNgo, Thi Thuy, Nguyen N. Bang, Peter Dart, Matthew Callaghan, Athol Klieve, Ben Hayes, and David McNeill. 2021. "Feed Preference Response of Weaner Bull Calves to Bacillus amyloliquefaciens H57 Probiotic and Associated Volatile Organic Compounds in High Concentrate Feed Pellets" Animals 11, no. 1: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11010051

APA StyleNgo, T. T., Bang, N. N., Dart, P., Callaghan, M., Klieve, A., Hayes, B., & McNeill, D. (2021). Feed Preference Response of Weaner Bull Calves to Bacillus amyloliquefaciens H57 Probiotic and Associated Volatile Organic Compounds in High Concentrate Feed Pellets. Animals, 11(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11010051