Ruminal Lipopolysaccharides Analysis: Uncharted Waters with Promising Signs

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Lipopolysaccharides Extraction Protocols

Ruminal Lipopolysaccharides Extraction, Purification, and Quantification

3. Ruminal Lipopolysaccharides’ Immunogenicity and Biosynthesis

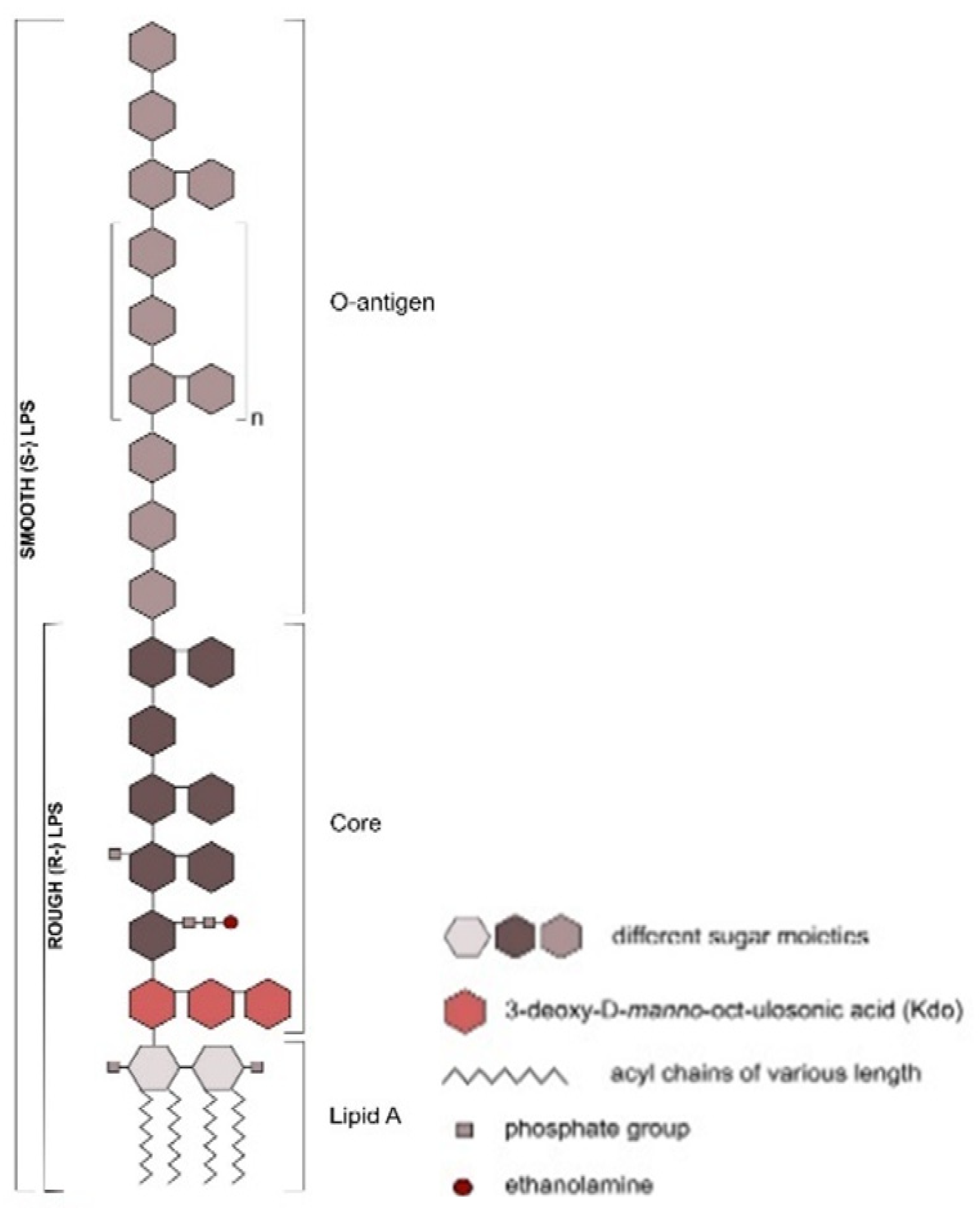

Ruminal Lipopolysaccharides’ Rough and Smooth Phenotypes

4. Lipopolysaccharide Sensing

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raetz, C.R.H.; Whitfield, C. Lipopolysaccharide Endotoxins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2002, 71, 635–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikaido, H. Outer membrane barrier as a mechanism of antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1989, 33, 1831–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papo, N.; Shai, Y.; Humphries, J.D.; Schofield, N.R.; Mostafavi-Pour, Z.; Green, L.J.; Garratt, A.N.; Mould, A.P.; Humphries, M.J. A Molecular Mechanism for Lipopolysaccharide Protection of Gram-negative Bacteria from Antimicrobial Peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 10378–10387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertani, B.; Ruiz, N. Function and Biogenesis of Lipopolysaccharides. EcoSal Plus 2018, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caradonna, L.; Amati, L.; Magrone, T.; Pellegrino, N.M.; Jirillo, E.; Caccavo, D. Enteric bacteria, lipopolysaccharides and related cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease: Biological and clinical significance. J. Endotoxin Res. 2000, 6, 205–214. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y.; Zhou, G.; He, C.; Yang, W.; He, Z.; Liu, Z. Serum Levels of Lipopolysaccharide and 1,3-β-D-Glucan Refer to the Severity in Patients with Crohn’s Disease. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuele, E.; Orsi, P.; Boso, M.; Broglia, D.; Brondino, N.; Barale, F.; Di Nemi, S.U.; Politi, P. Low-grade endotoxemia in patients with severe autism. Neurosci. Lett. 2010, 471, 162–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Miller, R.G.; Gascon, R.; Champion, S.; Katz, J.D.; Lancero, M.; Narvaez, A.; Honrada, R.; Ruvalcaba, D.; McGrath, M.S. Circulating endotoxin and systemic immune activation in sporadic amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (sALS). J. Neuroimmunol. 2009, 206, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerville, M.; Boudry, G. Gastrointestinal and hepatic mechanisms limiting entry and dissemination of lipopolysaccharide into the systemic circulation. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2016, 311, G1–G15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraja, T.G.; Titgemeyer, E.C. Ruminal acidosis in beef cattle: The current microbiological and nutritional outlook. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, E17–E38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosooghi-Poostindoz, V.; Foroughi, A.; Delkhoroshan, A.; Ghaffari, M.; Vakili, R.; Soleimani, A. Effects of different levels of protein with or without probiotics on growth performance and blood metabolite responses during pre- and post-weaning phases in male Kurdi lambs. Small Rumin. Res. 2014, 117, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, A.M.; Zanouny, A.; Singer, A. Growth performance, nutrients digestibility, and blood metabolites of lambs fed diets supplemented with probiotics during pre- and post-weaning period. Asian Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 30, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E.U. Regulations (EC). No 1831/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council: On Additives for Use in Animal Nutrition. Off. J. Eur. Commun. 2003, 268, 18. [Google Scholar]

- US Food and Drug Administration. New Animal Drugs and New Animal Drug Combination Products Administered in or on Medicated Feed or Drinking Water of Food Producing Animals; USFDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2013.

- Simpson, B.W.; Trent, M.S. Pushing the envelope: LPS modifications and their consequences. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 17, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregg, K.A.; Harberts, E.; Gardner, F.M.; Pelletier, M.R.; Cayatte, C.; Yu, L.; McCarthy, M.P.; Marshall, J.D.; Ernst, R.K. Rationally Designed TLR4 Ligands for Vaccine Adjuvant Discovery. mBio 2017, 8, e00492-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaizier, J.C.; Khafipour, E.; Li, S.; Gozho, G.N.; Krause, D.O. Subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA), endotoxins and health consequences. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2012, 172, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleen, J.L.; Upgang, L.; Rehage, J. Prevalence and consequences of subacute ruminal acidosis in German dairy herds. Acta Veter. Scand. 2013, 55, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraja, T.; Galyean, M.L.; Cole, N.A. Nutrition and Disease. Veter. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pr. 1998, 14, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozho, G.N.; Plaizier, J.; Krause, D.O.; Kennedy, A.D.; Wittenberg, K.M. Subacute Ruminal Acidosis Induces Ruminal Lipopolysaccharide Endotoxin Release and Triggers an Inflammatory Response. J. Dairy Sci. 2005, 88, 1399–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozho, G.; Krause, D.; Plaizier, J. Ruminal Lipopolysaccharide Concentration and Inflammatory Response During Grain-Induced Subacute Ruminal Acidosis in Dairy Cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 856–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebeli, Q.; Ametaj, B.N. Relationships between rumen lipopolysaccharide and mediators of inflammatory response with milk fat production and efficiency in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 3800–3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.; De Paula, E.M.; Lelis, A.; Da Silva, L.G.; Brandao, V.L.N.; Monteiro, H.; Fan, P.; Poulson, S.; Jeong, K.; Faciola, A. Effects of lipopolysaccharide dosing on bacterial community composition and fermentation in a dual-flow continuous culture system. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 334–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.; Hackmann, T.J.; Lobo, R.R.; Faciola, A.P. Lipopolysaccharide Stimulates the Growth of Bacteria That Contribute to Ruminal Acidosis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, T.L. Physiological Effects of Acidosis on Feedlot Cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 1976, 43, 902–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraja, T.G.; Lechtenberg, K.F. Acidosis in Feedlot Cattle. Veter. Clin. North Am. Food Anim. Pr. 2007, 23, 333–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, P.H.; Bergelin, B.; Christensen, K.A. Effect of feeding regimen on concentration of free endotoxin in ruminal fluid of cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 1994, 72, 487–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro, H.F.; Faciola, A.P. Ruminal acidosis, bacterial changes, and lipopolysaccharides. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 98, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanoni, I.; Bodio, C.; Broggi, A.; Ostuni, R.; Caccia, M.; Collini, M.; Venkatesh, A.; Spreafico, R.; Capuano, G.; Granucci, F. Similarities and differences of innate immune responses elicited by smooth and rough LPS. Immunol. Lett. 2012, 142, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanos, C.; Luderitz, O.; Westphal, O. A New Method for the Extraction of R Lipopolysaccharides. Eur. J. Biochem. 1969, 9, 245–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, J.; Ashwell, G. Isolation of a Bacterial Lipopolysaccharide from Xanthomonas campestris Containing 3-Acetamido-3,6-dideoxy-d-galactose and d-Rhamnose. J. Biol. Chem. 1966, 241, 1424–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, M.H.; Schweizer, H.P.; Tuanyok, A. Structural diversity of Burkholderia pseudomallei lipopolysaccharides affects innate immune signaling. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2017, 11, e0005571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezania, S.; Amirmozaffari, N.; Tabarraei, B.; Jeddi-Tehrani, M.; Zarei, O.; Alizadeh, R.; Masjedian, F.; Zarnani, A.-H. Extraction, Purification and Characterization of Lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhi. Avicenna J. Med. Biotechnol. 2011, 3, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goebel, W.F.; Binkley, F.; Perlman, E. Studies on the flexner group of dysentery bacilli. J. Exp. Med. 1945, 81, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribi, E.; Haskins, W.T.; Landy, M.; Milner, K.C. Preparation And Host-Reactive Properties Of Endotoxin With Low Content Of Nitrogen And Lipid. J. Exp. Med. 2004, 114, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westphal, O.; Jann, K. Bacterial Lipopolysaccharides Extraction with Phenol-Water and Further Applications of the Procedure. Methods Carbohydr. Chem. 1965, 5, 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, N.; Gray, G.; Wilkinson, S. Release of lipopolysaccharide during the preparation of cell walls of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Biomembr. 1967, 135, 1068–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, D.C.; Leive, L. Fractions of lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia coli O111:B4 prepared by two extraction pro-cedures. J. Biol. Chem. 1975, 250, 2911–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darveau, R.P.; Hancock, R.E. Procedure for isolation of bacterial lipopolysaccharides from both smooth and rough Pseu-domonas aeruginosa and Salmonella typhimurium strains. J. Bacteriol. 1983, 155, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berczi, I.; Bertók, L.; Bereznai, T. Comparative Studies On The Toxicity Of Escherichia Coli Lipopolysaccharide Endotoxin In Various Animal Species. Can. J. Microbiol. 1966, 12, 1070–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraja, T.G.; Fina, L.R.; Bartley, E.E.; Anthony, H.D. Endotoxic activity of cell-free rumen fluid from cattle fed hay or grain. Can. J. Microbiol. 1978, 24, 1253–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitchcock, P.J.; Brown, T.M. Morphological heterogeneity among Salmonella lipopolysaccharide chemotypes in sil-ver-stained polyacrylamide gels. J. Bacteriol. 1983, 154, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Liu, G.; Li, X.; Guan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, X.; Sun, G.; Wang, Z.; Liu, G. Inflammatory mechanism of Rumenitis in dairy cows with subacute ruminal acidosis. BMC Veter. Res. 2018, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefańska, B.; Człapa, W.; Pruszynska-Oszmalek, E.; Szczepankiewicz, D.; Fievez, V.; Komisarek, J.; Stajek, K.; Nowak, W. Subacute ruminal acidosis affects fermentation and endotoxin concentration in the rumen and relative expression of the CD14/TLR4/MD2 genes involved in lipopolysaccharide systemic immune response in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 1297–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emmanuel, D.; Madsen, K.; Churchill, T.; Dunn, S.; Ametaj, B.N. Acidosis and Lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia coli B:055 Cause Hyperpermeability of Rumen and Colon Tissues. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 5552–5557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent-Dennis, C.; Aschenbach, J.; Griebel, P.J.; Penner, G. Effects of lipopolysaccharide exposure in primary bovine ruminal epithelial cells. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, 103, 9587–9603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khafipour, E.; Li, S.; Plaizier, J.C.; Krause, D.O. Rumen Microbiome Composition Determined Using Two Nutritional Models of Subacute Ruminal Acidosis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7115–7124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khafipour, E.; Plaizier, J.; Aikman, P.; Krause, D.O. Population structure of rumen Escherichia coli associated with subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA) in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaizier, J.C.; Li, S.; Danscher, A.M.; Derakshani, H.; Andersen, P.H.; Khafipour, E. Changes in microbiota in rumen digesta and feces due to a grain-based subacute ruminal acidosis (SARA) challenge. Microb. Ecol. 2017, 74, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonesson, H.R.A.; Zähringer, U.; Grimmecke, H.D.; Westphal, O.R.E. Bacterial endotox. In Chemical Structure, Biological, Activity; Bringham, K., Ed.; Marcel Dekker Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Berezow, A.B.; Ernst, R.K.; Coats, S.R.; Braham, P.H.; Karimi-Naser, L.M.; Darveau, R.P. The structurally similar, penta-acylated lipopolysaccharides of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Bacteroides elicit strikingly different innate immune responses. Microb. Pathog. 2009, 47, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pier, G.B. Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipopolysaccharide: A major virulence factor, initiator of inflammation and target for effective immunity. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2007, 297, 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenberg, M.A.; Merlin, T.; Gumenscheimer, M.; Kalis, C.; Landmann, R.; Galanos, C. Role of lipopolysaccharide susceptibility in the innate immune response to Salmonella typhimurium infection: LPS, a primary target for recognition of Gram-negative bacteria. Microbes Infect. 2001, 3, 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jann, K. Polysaccharide Antigens of Escherichia coli. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1987, 9, S517–S526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.M.R.; Goldberg, J.B. Purification and Visualization of Lipopolysaccharide from Gram-negative Bacteria by Hot Aqueous-phenol Extraction. J. Vis. Exp. 2012, e3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leker, K.; Lozano-Pope, I.; Bandyopadhya, K.; Choudhury, B.; Obonyo, M. Comparison of lipopolysaccharides composition of two different strains of Helicobacter pylori. BMC Microbiol. 2017, 17, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munford, R.S.; Varley, A.W. Shield as Signal: Lipopolysaccharides and the Evolution of Immunity to Gram-Negative Bacteria. PLoS Pathog. 2006, 2, e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emaeshima, N.; Fernandez, R.C. Recognition of lipid A variants by the TLR4-MD-2 receptor complex. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2013, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietschel, E.T.; Kirikae, T.; Schade, F.U.; Mamat, U.; Schmidt, G.; Loppnow, H.; Ulmer, A.J.; Zähringer, U.; Seydel, U.; Di Padova, F.; et al. Bacterial endotoxin: Molecular relationships of structure to activity and function. FASEB J. 1994, 8, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brozek, K.A.; Raetz, C.R.H. Biosynthesis of lipid A in Escherichia coli. Acyl carrier protein-dependent incorporation of laurate and myristate. J. Biol. Chem. 1990, 265, 15410–15417. [Google Scholar]

- Zähringer, U.; Lindner, B.; Rietschel, E.T. Molecular structure of lipid A, the endotoxic center of bacterial lipopolysaccha-rides. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 1994, 50, 211–276. [Google Scholar]

- Molinaro, A.; Holst, O.; Di Lorenzo, F.; Callaghan, M.; Nurisso, A.; D’Errico, G.; Zamyatina, A.; Peri, F.; Berisio, R.; Jerala, R.; et al. Chemistry of Lipid A: At the Heart of Innate Immunity. Chem. A Eur. J. 2015, 21, 500–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, J.M. The immune response toPrevotellabacteria in chronic inflammatory disease. Immunology 2017, 151, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Wang, Z.; Dong, C.; Li, F.; Wang, W.; Yuan, Z.; Mo, F.; Weng, X. Rumen Bacteria Communities and Performances of Fattening Lambs with a Lower or Greater Subacute Ruminal Acidosis Risk. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCann, J.C.; Eluan, S.; Cardoso, F.C.; Ederakhshani, H.; Ekhafipour, E.; Loor, J.J. Induction of Subacute Ruminal Acidosis Affects the Ruminal Microbiome and Epithelium. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steimle, A.; Autenrieth, I.B.; Frick, J.-S. Structure and function: Lipid a modifications in commensals and pathogens. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2016, 306, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sauter, K.-S.; Brcic, M.; Franchini, M.; Jungi, T.W. Stable transduction of bovine TLR4 and bovine MD-2 into LPS-nonresponsive cells and soluble CD14 promote the ability to respond to LPS. Veter. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2007, 118, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Darveau, R.P. Contribution of Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide to periodontitis. Periodontol. 2000 2010, 54, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandell, L.; Moran, A.P.; Cocchiarella, A.; Houghton, J.; Taylor, N.; Fox, J.G.; Wang, T.C.; Kurt-Jones, E.A. Intact Gram-Negative Helicobacter pylori, Helicobacter felis, and Helicobacter hepaticus Bacteria Activate Innate Immunity via Toll-Like Receptor 2 but Not Toll-Like Receptor 4. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 6446–6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, K.; Qureshi, N.; Ribi, E.; Cantrell, J.L. Separation and Characterization of Toxic and Nontoxic Forms of Lipid A. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1984, 6, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, R.F.; Sá-Correia, I.; Valvano, M.A. Lipopolysaccharide modification in Gram-negative bacteria during chronic infection. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2016, 40, 480–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, C.; Trent, M.S. Biosynthesis and Export of Bacterial Lipopolysaccharides. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2014, 83, 99–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Védrine, M.; Berthault, C.; Leroux, C.; Répérant-Ferter, M.; Gitton, C.; Barbey, S.; Rainard, P.; Gilbert, F.B.; Germon, P. Sensing of Escherichia coli and LPS by mammary epithelial cells is modulated by O-antigen chain and CD14. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worku, M.; Morris, A. Binding of different forms of lipopolysaccharide and gene expression in bovine blood neutrophils. J. Dairy Sci. 2009, 92, 3185–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roach, J.C.; Glusman, G.; Rowen, L.; Kaur, A.; Purcell, M.K.; Smith, K.D.; Hood, L.E.; Aderem, A. The evolution of vertebrate Toll-like receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 9577–9582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poltorak, A.; He, X.; Smirnova, I.; Liu, M.-Y.; Van Huffel, C.; Du, X.; Birdwell, D.; Alejos, E.; Silva, M.; Galanos, C.; et al. Defective LPS Signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr Mice: Mutations in Tlr4 Gene. Science 1998, 282, 2085–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugin, J.; Ulevitch, R.J.; Tobias, P.S. A critical role for monocytes and CD14 in endotoxin-induced endothelial cell activation. J. Exp. Med. 1993, 178, 2193–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, E.A.; Miller, D.S.; Jahr, T.G.; Sundan, A.; Bazil, V.; Espevik, T.; Finlay, B.B.; Wright, S.D. Soluble CD14 participates in the response of cells to lipopolysaccharide. J. Exp. Med. 1992, 176, 1665–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, K. Roles for accessory molecules in microbial recognition by Toll-like receptors. J. Endotoxin Res. 2006, 12, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, R.R.; Leong, S.R.; Flaggs, G.W.; Gray, P.W.; Wright, S.D.; Mathison, J.C.; Tobias, P.S.; Ulevitch, R.J. Structure and function of lipopolysaccharide binding protein. Science 1990, 249, 1429–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimazu, R.; Akashi, S.; Ogata, H.; Nagai, Y.; Fukudome, K.; Miyake, K.; Kimoto, M. MD-2, a Molecule that Confers Lipopolysaccharide Responsiveness on Toll-like Receptor 4. J. Exp. Med. 1999, 189, 1777–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.D.; Ramos, R.A.; Tobias, P.S.; Ulevitch, R.J.; Mathison, J.C. CD14, a receptor for complexes of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and LPS binding protein. Science 1990, 249, 1431–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.S.; Song, D.H.; Kim, H.M.; Choi, B.-S.; Lee, H.; Lee, J.-O. The structural basis of lipopolysaccharide recognition by the TLR4–MD-2 complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 458, 1191–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krüger, C.L.; Zeuner, M.-T.; Cottrell, G.S.; Widera, D.; Heilemann, M. Quantitative single-molecule imaging of TLR4 reveals ligand-specific receptor dimerization. Sci. Signal. 2017, 10, eaan1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

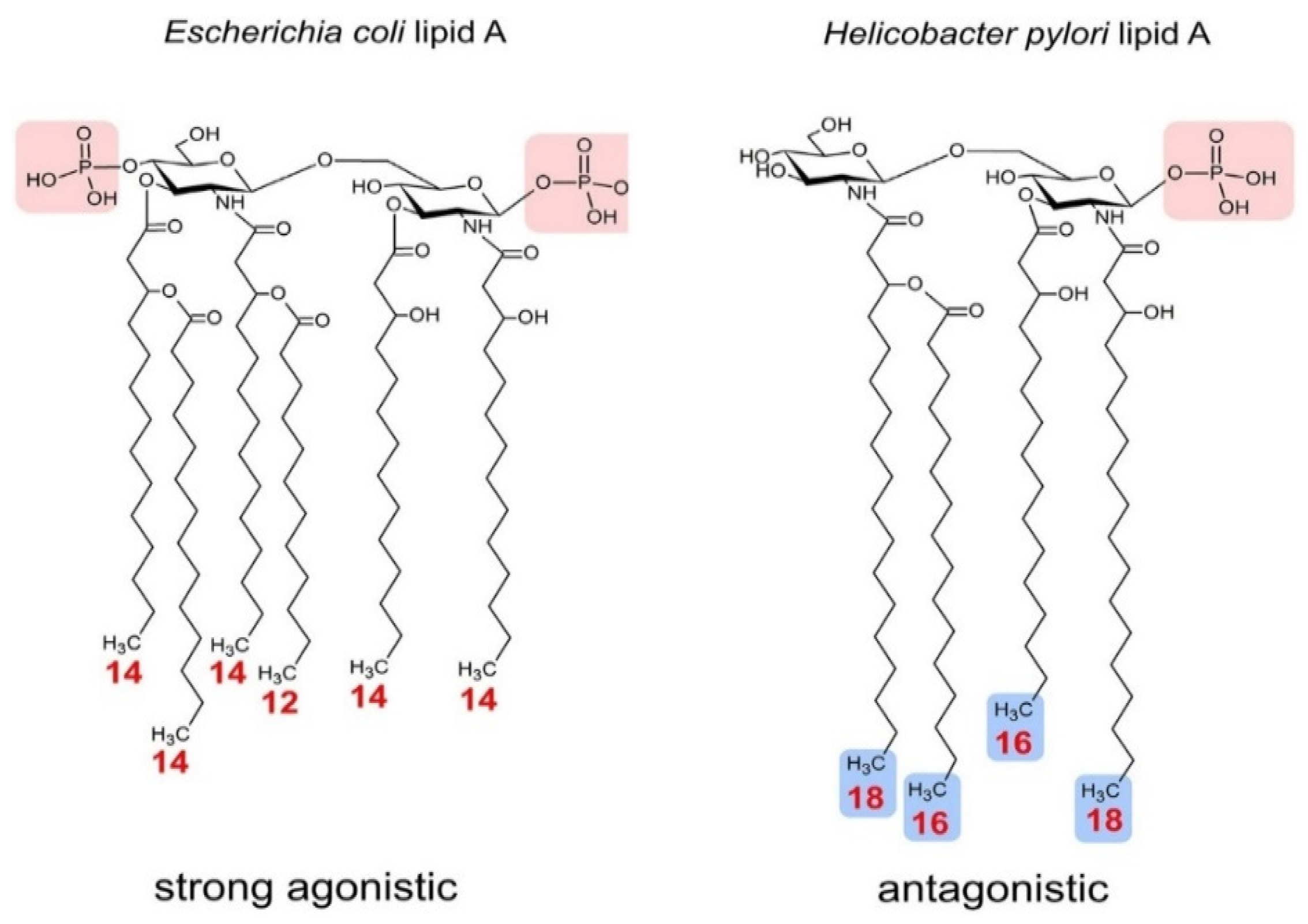

| Bacteria Species LPS | Acylation Pattern | Biological Properties | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | Hamster | Mouse | |||

| E. coli O55:B5 | Hexa-acylation | Strong Agonist | Strong Agonist | Strong Agonist | [67] |

| Porphyromonas gingivalis (Periodontopathogen) | Penta-or Tetra-acylation | Weak Agonist- Antagonist | - | - | [68] |

| Helicobacter pylori | Tetra-acylation | Weak Agonist | - | - | [69] |

| Salmonella minnesota (Di-phosphoryl-lipid A) | Hexa-acylation | Agonist | - | Agonist | [70] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarmikasoglou, E.; Faciola, A.P. Ruminal Lipopolysaccharides Analysis: Uncharted Waters with Promising Signs. Animals 2021, 11, 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11010195

Sarmikasoglou E, Faciola AP. Ruminal Lipopolysaccharides Analysis: Uncharted Waters with Promising Signs. Animals. 2021; 11(1):195. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11010195

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarmikasoglou, Efstathios, and Antonio P. Faciola. 2021. "Ruminal Lipopolysaccharides Analysis: Uncharted Waters with Promising Signs" Animals 11, no. 1: 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11010195

APA StyleSarmikasoglou, E., & Faciola, A. P. (2021). Ruminal Lipopolysaccharides Analysis: Uncharted Waters with Promising Signs. Animals, 11(1), 195. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11010195