Blind Trading: A Literature Review of Research Addressing the Welfare of Ball Pythons in the Exotic Pet Trade

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Literature Analysis

2.3. Statistical Analysis

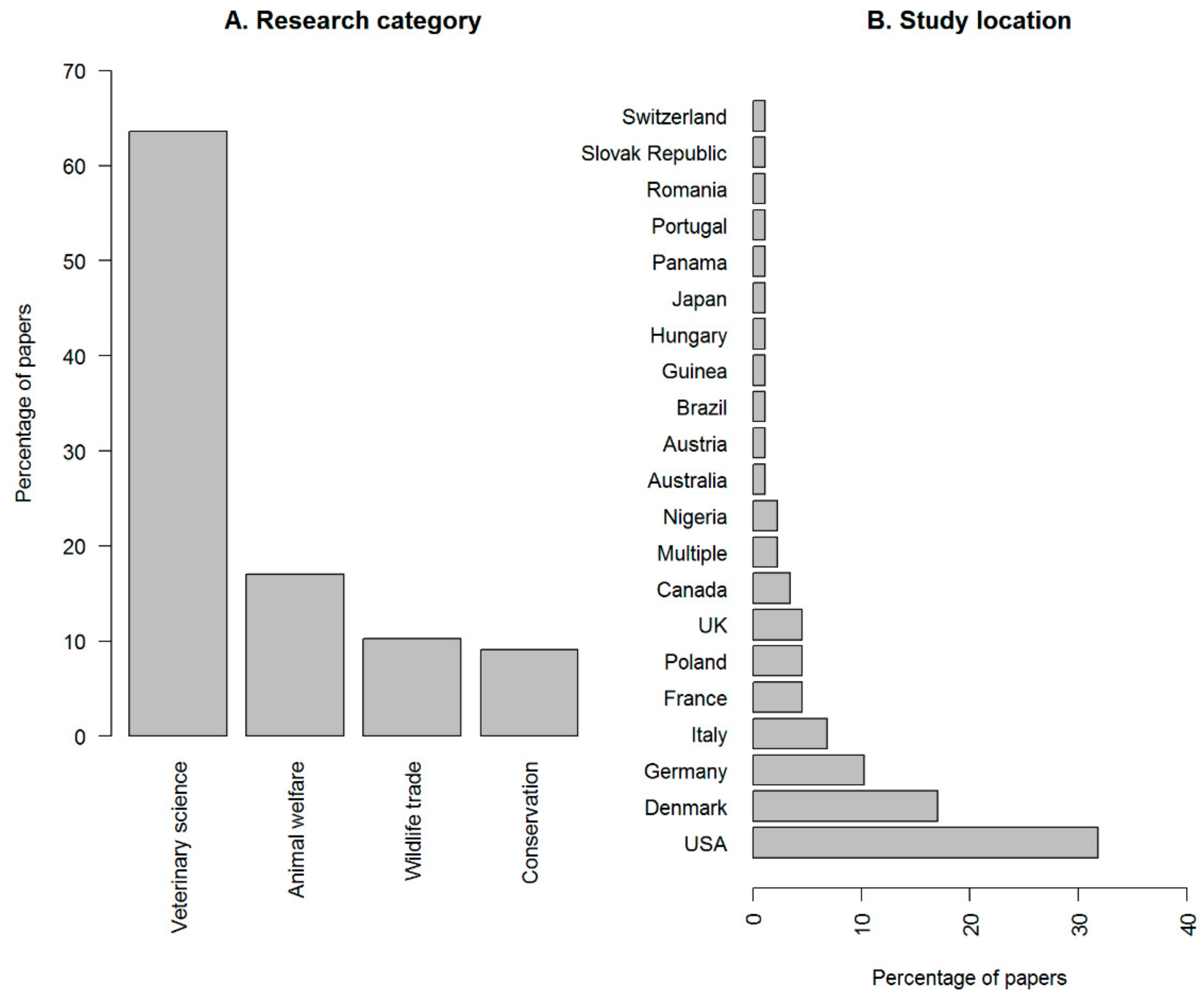

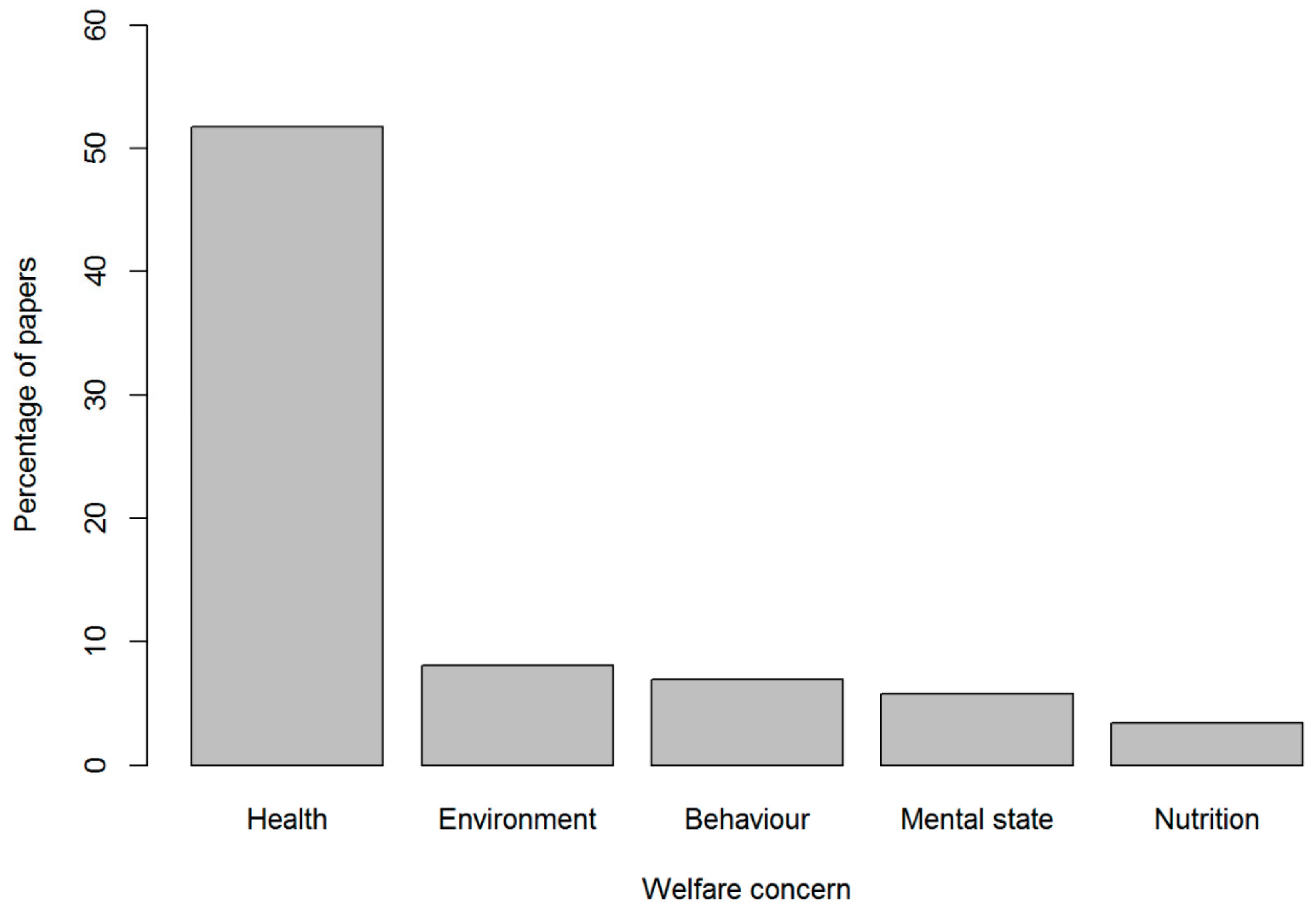

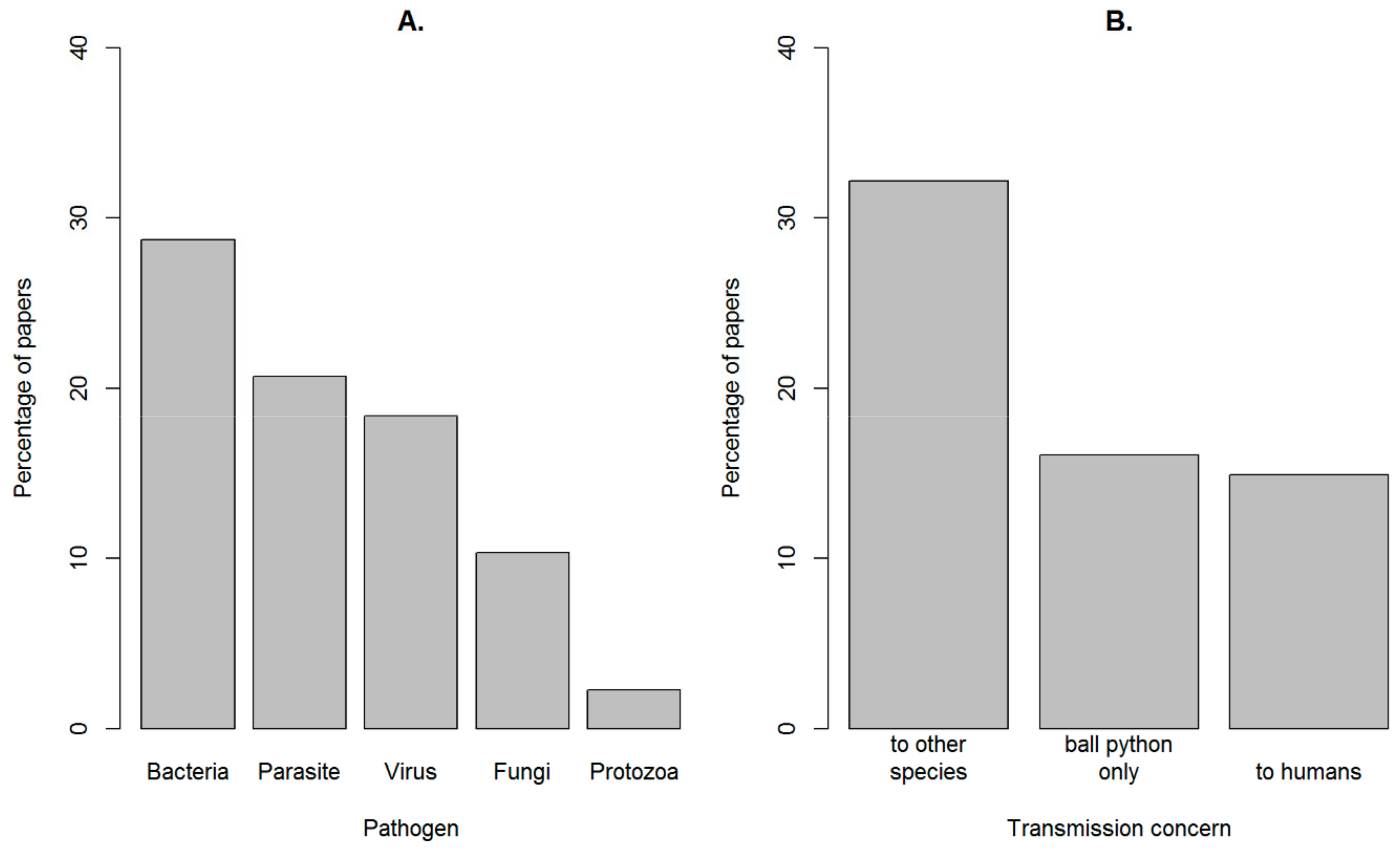

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Animal Welfare Domains

4.2. The Trade Chain

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Table of assigned categories for primary focus of papers used in this study and definitions

| Assigned Category | Definitions |

| Welfare | Primarily focused on the broader animal welfare (non-clinical: stress, harm, etc.) impacts on Ball pythons in captivity for commercial, private or zoological purposes. |

| Conservation | Primarily focused on Ball python conservation, wild populations and their management, and/or species status. |

| Veterinary science | Primarily focused on the pathology, clinical symptoms or treatments and procedures relating to Ball pythons. |

| Trade | Primarily focused on the trade of Ball pythons, other than welfare and conservation impacts. For example, scope and scale of trade, economic impacts and legislation or regulation. |

Appendix B. Table of negative behaviours and physical health afflictions mentioned in each of the papers in the dataset

| Domain | Terms (taken directly from source papers) |

| Behaviour | Abnormal posture [46]; Anorexia [46,47]; Disorientation [47]; head tremors [47]; Incoordination [47]; Lethargy [46]; Open-mouthed breathing [48]; Regurgitation [47]; Stargazing [47] |

| Health | Hyperglycaemia [49]; Anemia [49]; Azurophilia [49]; bacterial infection (unspecified) [46,50,51,52]; bilateral corneal opacity [8]; bilateral corneal ulceration [53]; bronchial epithelial hyperplasia [54]; cardiac malformations [55]; **caudal paralysis [46]; central nervous system disease [46,47]; corneal ulceration [54]; dermatitis [54]; **dysecdysis [53]; ectoparasite presence [56]; elevated creatine kinase activity [49]; esophagitis [48,57]; *facial cellulitis [58]; **facultative parthenogenesis [59]; focal dermatitis [46]; gastrointestinal tract diseases (unspecified) [60]; granulocytic meningomyelitis [46]; hamartoma [49]; hepatic lipidosis [54]; heteropenia [49]; moderate heterophilic and lymphocytic anterior uveitis [53]; heterophilic and lymphocytic keratoconjunctivitis with neovascularization and intralesional bacterial colonies [53]; histiocytic meningomyelitis [46]; hyperplasia [54]; Hyperuricemia [49]; leptospirosis [61]; lesions [54]; leukocytosis [49]; lymphocytic biliary dochitis [46]; lymphocytic encephalitis [46]; lymphocytic meningomyelitis [46]; lymphocytolysis [46]; lymphocytosis [49]; lympho proliferative disorder [47]; marked segmental degeneration [53]; mite infestation [49,62]; mucosal hemorrhages [48]; mucous metaplasia [54]; necrosis of stratum basale and spinosum [53]; necrotizing conjunctivitis [54]; nephritis nephrosis [54]; neuronal necrosis [46]; neuronophagia [46]; ocular disease [63]; opisthotonus [47]; oral bacteria [64]; pharyngitis [48,54]; pneumonia [46,47,48,54,57,65,66]; pulmonary hemorrhage [54]; renal lesions [67]; renal tubular degeneration [53]; respiratory disease [48,54,65]; salpingitis [54]; segmented epidermal erosion and ulceration [53]; sinusitis [48,54]; squamous cell carcinoma [49]; stomatitis [46,47,48,54]; superficial perivascular lymphocytic dermatitis [53]; subspectacular nematodiasis [68] tick parasatism [69,70,71,72]; tracheitis [48,54,57]; tracytoplasmic inclusion bodies [47]; under-developed ocular structures [73]; **wobble head syndrome [10]; bite wounds [49,52]; burns [49]; dermatologic lesions [49]; Inflammation [74,75]; skin incision made by researchers [76] |

Appendix C. Table of the specific pathogens (categorized into bacteria, parasites, protozoa and viruses) mentioned in the papers in the dataset

| Pathogen | Species, serovars and diseases (taken directly from source papers) |

| Bacteria | Acinetobacter calcoaceticus [64], A. lwoffii [77], Aeromonas hydrophila [64], A. veronii [77], Anaplasma phagocytophilum [78], Bacteroides spp. [64], Bordetella hinzii [65], chlamydophilosis [48], Citrobacter freundii [64,65,77], Clostridium spp. [64], Elizabethkingia meningoseptica [65], Enterobacter cloacae [64,65], Enterococcus pallens [77], Escherichia coli [51,64], Klebsiella oxytoca [49,65], K. pneumoniae [65], Klebsiella spp. [58], Leptospira grippotyphosa [61], Lysobacter pythonis [79], Moraxella osloensis [77], Morganella morganii [49,64], Mycoplasmosis [48], Proteus vulgaris [65], Providencia rettgeri [80], Pseudomonas aeruginosa [49,58,65,67], P. floureszens [65], P. japonica [77], Pseudomonas spp. [64], Salmonella Muenchen [65], Salmonella Paratyphi B [50,65], Salmonella spp. [49,64,65], Salmonella ssp. IIIb [65], Salmonella ssp. IV [65], Serratia plymuthica [77], Staphylococcus spp. [49,64,65], Staphylococcus warneri [77], Stenotrophomonas maltophilia [52,65,77], Tsukamurella paurometabola [77] |

| Parasites | Amblyomma dissimile [56], A. exornatum [69], A. latum [56,69,71,78], A. rotundatum [56], Amblyomma spp. [69,71,78], A. transversal [69,78], Armillifer spp. [81,82], Eutrombicula cinnabaris [56], E. splendens [56], Geckobia hemidactyli [56], Hirstiella stamii [56], Ixodes scapularis [70], Linguatula spp. [81], Nematoda spp. [48,83], Ophionyssus natricis [62,75], Porocephalus spp. [81], Raillietiella spp. [64], Serpentirhabdias dubielzigi [68,83], Pentastomida spp. [81] |

| Protozoa | Hepatozoon ayorgbor [84], Hepatozoon spp. [84,85,86], Trypanosoma cf. varani [87], Trypanosoma spp. [84,87] |

| Fungi | No species names reported |

| Viruses | Adenovirus [57,65], Barnivirus [48], Boid inclusion body disease [49,66], Chikungunya Virus [88], Circovirus [89], Ferlavirus [65], Filoviridae [54], Flaviviruses [57], Herpes viruses [57], Iridoviruses [57], Inclusion body disease [46,47,65,90,91], lymphocytic ganglioneuritis [46], Nidovirus [48,54,57], Paramyxovirus spp. [48,54,57,92,93], Reptarenaviruses [46,47], Reoviridae spp. [48,57], Retrovirus [91], Rhabdoviridae spp. [54], Torovirinae [48,54,57] |

References

- Warwick, C.; Steedman, C.; Jessop, M.; Arena, P.; Pilny, A.; Nicholas, E. Exotic pet suitability: Understanding some problems and using a labeling system to aid animal welfare, environment, and consumer protection. J. Vet. Behav. 2018, 26, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorhouse, T.P.; Balaskas, M.; D’Cruze, N.C.; Macdonald, D.W. Information Could Reduce Consumer Demand for Exotic Pets. Conserv. Lett. 2016, 10, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J.E.; St, John, F.A.V.; Griffiths, R.A.; Roberts, D.L. Captive reptile mortality rates in the home and implications for the wildlife trade. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auliya, M. Hot Trade in Cool Creatures: A Review of the Live Reptile Trade in the European Union in the 1990s with a Focus on Germany; TRAFFIC Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2003; Available online: https://www.traffic.org/site/assets/files/9705/a-review-of-live-reptile-trade-in-the-eu-in-the-1990s.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2019).

- Auliya, M.; Altherr, S.; Ariano-Sánchez, D.; Baard, E.; Brown, C.; Brown, R.; Cantu, C.; Gentile, G.; Gildenhuys, P.; Henningheim, E.; et al. Trade in live reptiles, its impact on wild populations, and the role of the European market. Biol. Conserv. 2016, 204, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, T.J.; Auliya, M.; Burgess, N.D.; Aust, P.W.; Pertoldi, C.; Strand, J. Exploring the international trade in African snakes not listed on CITES: Highlighting the role of the internet and social media. Biodivers. Conserv. 2019, 28, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PFMA. UK Pet Population Statistics. Pet Food Manufacturers’ Association. 2017. Available online: http://www.pfma.org.uk/pet-population-2017 (accessed on 11 November 2019).

- APPA. National Pet Owners Survey 2017–2018; American Pet Products Association: Stanford, CT, USA, 2017; Available online: http://www.americanpetproducts.org/press_industrytrends.asp (accessed on 25 June 2017).

- Warwick, C.; Arena, P.; Steedman, C. Spatial considerations for captive snakes. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2019, 30, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, M.P.; Williams, D.L. Neurological dysfunction in a Ball python (Python regius) colour morph and implications for welfare. J. Exot. Pet Med. 2014, 23, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Animal Protection. Exploiting Africa’s Wildlife—The ‘Big 5’ and ‘Little 5’. 2019. Available online: https://d31j74p4lpxrfp.cloudfront.net/sites/default/files/big_5_little_5_report.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2019).

- Paré, J.A. An overview of pet reptile species and proper handling. In Proceedings of the North American Veterinary Conference, Orlando, FL, USA, 7–1 January 2006; Volume 20, pp. 1657–1660. [Google Scholar]

- Trape, J.F.; Mané, Y. Savane et desert. In Guide des serpents d’Afrique occidentale; IRD Editions: Paris, France, 2006; p. 226. [Google Scholar]

- Burghardt, G.M. Keeping reptiles and amphibians as pets: Challenges and rewards. Vet. Rec. 2017, 181, 447–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broghammer, S. Python Regius: Atlas of Colour Morphs, Keeping and Breeding; Aufl. Natur-und-Tier-Verlag: Münster, Germany, 2018; p. 440. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, E.R.; Baker, S.E.; Macdonald, D.W. Global trade in exotic pets 2006–2012. Conserv. Biol. 2014, 28, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehead, M.L. Factors contributing to poor welfare of pet reptiles. Testudo 2018, 8, 47–61. [Google Scholar]

- Warwick, C.; Jessop, M.; Arena, P.; Pliny, A.; Nicholas, E.; Lambiris, A. Future of keeping pet reptiles and amphibians: animal welfare and public health perspective. Veterinary Record. 2017, 181, 454–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RSPCA Royal Python Care Sheet. 2018. Available online: https://www.rspca.org.uk/adviceandwelfare/pets/other/royalpython?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIo7r8mZP73AIV65XtCh1jvgcpEAAYASAAEgKlp_D_BwE (accessed on 11 November 2019).

- D’Cruze, N.; Paterson, S.; Green, J.; Megson, D.; Warwick, C.; Coulthard, E.; Norrey, J.; Auliya, M.; Carder, G. Dropping the Ball: The welfare of Ball Pythons traded in the EU and North America. Animals. in press.

- Baker, S.E.; Cain, R.; Van Kesteren, F.; Zommers, Z.A.; D’Cruze, N.; Macdonald, D.W. Rough trade: Animal welfare in the global wildlife trade. BioScience 2013, 63, 928–938. [Google Scholar]

- Arena, P.C.; Warwick, C.; Steedman, C. Welfare and environmental implications of farmed sea turtles. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2014, 27, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warwick, C.; Lindley, S.; Steedman, C. Signs of stress. Environ. Health News 2011, 10, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Warwick, C.; Arena, P.; Lindley, S.; Jessop, M.; Steedman, C. Assessing reptile welfare using behavioural criteria. InPractice 2013, 35, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuppli, C.A.; Fraser, D.; Bacon, H.J. Welfare of non-traditional pets. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2014, 33, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN/SSC. Guidelines for Reintroductions and Other Conservation Translocations, Version 1.0; IUCN Species Survival Commission: Gland, Switzerland, 2013; p. viiii + 57. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor, H.S.; Carder, G.; Cornish, A. Searching for Animal Sentience: A Systematic Review of the Scientific Literature. Animals 2013, 3, 882–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burghardt, G.M. Environmental enrichment and cognitive complexity in reptiles and amphibians: Concepts, review, and implications for captive populations. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2013, 147, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vere, A.J.; Kuczaj, S.A. Where are we in the study of animal emotions? Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Cogn. Sci. 2016, 7, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benn, A.L.; McLelland, D.J.; Whittaker, A.L. A Review of Welfare Assessment Methods in Reptiles, and Preliminary Application of the Welfare Quality® Protocol to the Pygmy Blue-Tongue Skink, Tiliqua adelaidensis, Using Animal-Based Measures. Animals 2019, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christoffel, R.A.; Lepczyk, C.A. Representation of herpetofauna in wildlife research journals. J. Wildl. Manag. 2012, 76, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warwick, C. Reptilian ethology in captivity: Observations of some problems and an evaluation of their aetiology. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1990, 26, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, H.; Carder, G.; D’Cruze, N. Given the Cold Shoulder: A Review of the Scientific Literature for Evidence of Reptile Sentience. Animals 2019, 9, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warwick, C.; Frye, F.L.; Murphy, J.B. Health and Welfare of Captive Reptiles; Springer Science & Business Media: London, UK, 2001; p. 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellor, D.J. Operational details of the five domains model and its key applications to the assessment and management of animal welfare. Animals 2017, 78, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Divers, S.J. Clinical aspects of reptile behavior. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Exot. Anim. Pract. 2001, 43, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arena, P.; Steedman, C.; Warwick, C. Amphibian and Reptile Pet Markets in the EU an Investigation and Assessment; Animal Protection Agency. 2012. Available online: https://www.apa.org.uk/pdfs/AmphibianAndReptilePetMarketsReport.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2020).

- Mutschmann, F. Snake Diseases—Preventing and Recognizing Illness; Chimaira Publishing: Frankfurt, Germany, 2008; p. 306. [Google Scholar]

- Arena, P.C.; Warwick, C. Miscellaneous factors affecting health and welfare. In Health and Welfare of Captive Reptiles; Warwick, C., Frye, F.L., Murphy, J.B., Eds.; Chapman & Hall/Kluwer: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 263–283. [Google Scholar]

- Warwick, C. Psychological and behavioural principles and problems. In Health and Welfare of Captive Reptiles; Warwick, C., Frye, F.L., Murphy, J.B., Eds.; Chapman & Hall/Kluwer: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 205–238. [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz, M.; Pütsch, M.; Bisschopinck, T. Transport Mortality During the Import of Wild Caught Birds and Reptiles to Germany: An Investigation (Including a Study on Pre-Export-Conditions in the United Republic of Tanzania); German Federal Agency for Nature Conservation: Bonn, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Scherz, M. Duckbill Mutation in Snakes. Available online: http://markscherz.tumblr.com/post/84960749508/what-is-the-duckbill-mutation (accessed on 21 January 2020).

- Wensley, S.; Dawson, S.; Stidworthy, M.; Soutar, R. Welfare of exotic pets. Vet. Rec. 2016, 17821, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, K. Folklore husbandry and a philosophical model for the design of captive management regimes. Herpetol. Rev. 2013, 44, 448–452. [Google Scholar]

- Mendyk, R.W. Challenging folklore reptile husbandry in zoological parks. In Zoo Animals: Husbandry, Welfare and Public Interactions; Berger, M., Corbett, S., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 265–292. [Google Scholar]

- Stenglein, M.D.; Guzman, D.S.M.; Garcia, V.E.; Layton, M.L.; Hoon-Hanks, L.L.; Boback, S.M.; Keel, M.K.; Drazenovich, T.; Hawkins, M.G.; DeRisi, J.L. Differential disease susceptibilities in experimentally reptarenavirus-infected boa constrictors and ball pythons. J. Virol. 2017, 91, 00451-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Fu, D.; Stenglein, M.D.; Hernandez, J.A.; DeRisi, J.L.; Jacobson, E.R. Detection and prevalence of boid inclusion body disease in collections of boas and pythons using immunological assays. Vet. J. 2016, 218, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoon-Hanks, L.L.; Layton, M.L.; Ossiboff, R.J.; Parker, J.S.; Dubovi, E.J.; Stenglein, M.D. Respiratory disease in ball pythons (Python regius) experimentally infected with ball python nidovirus. Virology 2018, 517, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, S.D.; Bourdeau, P.; Bruet, V.; Kass, P.H.; Tell, L.; Hawkins, M.G. Reptiles with dermatological lesions: a retrospective study of 301 cases at two university veterinary teaching hospitals (1992–2008). Vet. Dermatol. 2011, 22, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnasamy, V.; Stevenson, L.; Koski, L.; Kellis, M.; Schroeder, B.; Sundararajan, M.; Ladd-Wilson, S.; Sampsel, A.; Mannell, M.; Classon, A.; et al. Notes from the field: investigation of an outbreak of Salmonella Paratyphi B variant L (+) tartrate+(Java) associated with ball python exposure—United States, 2017. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, C.K.; Skals, M.; Wang, T.; Cheema, M.U.; Leipziger, J.; Praetorius, H.A. Python erythrocytes are resistant to α-hemolysin from Escherichia coli. J. Membr. Biol. 2011, 244, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinger, C.J.; Dengler, B.; Bauer, T.; Mueller, R.S. Successful treatment of a necrotizing, multi-resistant bacterial pyoderma in a python with cold plasma therapy. Tierarztl. Prax. Ausg. K. 2018, 6, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, D.W.; Baines, F.M.; Pandher, K. Photodermatitis and photokeratoconjunctivitis in a ball python (Python regius) and a blue-tongue skink (Tiliqua spp.). J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2009, 40, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenglein, M.D.; Jacobson, E.R.; Wozniak, E.J.; Wellehan, J.F.; Kincaid, A.; Gordon, M.; Porter, B.F.; Baumgartner, W.; Stahl, S.; Kelley, K.; et al. Ball python nidovirus: a candidate etiologic agent for severe respiratory disease in Python regius. MBio 2014, 5, e01484-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, B.; Wang, T. Hemodynamic consequences of cardiac malformations in two juvenile ball pythons (Python regius). J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2009, 752–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corn, J.L.; Mertins, J.W.; Hanson, B.; Snow, S. First reports of ectoparasites collected from wild-caught exotic reptiles in Florida. J. Med. Entomol. 2011, 48, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uccellini, L.; Ossiboff, R.J.; De Matos, R.E.; Morrisey, J.K.; Petrosov, A.; Navarrete-Macias, I.; Jain, K.; Hicks, A.L.; Buckles, E.L.; Tokarz, R.; et al. Identification of a novel nidovirus in an outbreak of fatal respiratory disease in ball pythons (Python regius). Virol. J. 2014, 11, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardi, E.; Vetere, A.; Aquaro, V.; Lubian, E.; Lauzi, S.; Ravasio, G.; Zani, D.D.; Manfredi, M.; Tecilla, M.; Roccabianca, P.; et al. Use of Thrombocyte–Leukocyte-Rich Plasma in the Treatment of Chronic Oral Cavity Disorders in Reptiles: Two Case Reports. J. Exot. Pet Med. 2019, 29, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, W.; Schuett, G.W.; Ridgway, A.; Buxton, D.W.; Castoe, T.A.; Bastone, G.; Bennett, C.; McMahan, W. New insights on facultative parthenogenesis in pythons. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. Lond. 2014, 112, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banzato, T.; Russo, E.; Finotti, L.; Zotti, A. Development of a technique for contrast radiographic examination of the gastrointestinal tract in ball pythons (Python regius). Am. J. Vet. Res. 2012, 73, 996–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajayi, O.L.; Antia, R.E.; Ojo, O.E.; Awoyomi, O.J.; Oyinlola, L.A.; Ojebiyi, O.G. Prevalence and renal pathology of pathogenic Leptospira spp. in wildlife in Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria. Onderstepoort. J. Vet. Res. 2017, 84, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, R.J.; Cleghorn, J.E.; Bermudez, S.E.; Perotti, M.A. Occurrence of the mite Ophionyssus natricis (Acari: Macronyssidae) on captive snakes from Panama. Acarologia 2017, 57, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauridsen, H.; Da Silva, M.A.O.; Hansen, K.; Jensen, H.M.; Warming, M.; Wang, T.; Pedersen, M. Ultrasound imaging of the anterior section of the eye of five different snake species. BMC Vet. Res. 2014, 10, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dipineto, L.; Russo, T.P.; Calabria, M.; De Rosa, L.; Capasso, M.; Menna, L.F.; Borrelli, L.; Fioretti, A. Oral flora of P ython regius kept as pets. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 58, 462–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, V.; Marschang, R.E.; Abbas, M.D.; Ball, I.; Szabo, I.; Helmuth, R.; Plenz, B.; Spergser, J.; Pees, M. Detection of pathogens in Boidae and Pythonidae with and without respiratory disease. Vet. Rec. 2013, 72, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, F.; Schneiter, M.; Hetzel, U.; Keller, S.; Frenz, M.; Rička, J.; Hatt, J.M. Investigation of the tracheal mucociliary clearance in snakes with and without boid inclusion body disease and lung pathology. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2018, 49, 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, A.; Di Ianni, F.; Pelizzone, I.; Bertocchi, M.; Santospirito, D.; Rogato, F.; Flisi, S.; Spadini, C.; Iemmi, T.; Moggia, E.; et al. The prevalence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and multidrug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in healthy captive ophidian. PeerJ 2019, 7, e6706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, J.C.; Mans, C.; Dreyfus, J.; Reavill, D.R.; Lucio-Forster, A.; Bowman, D.D. Subspectacular nematodiasis caused by a novel Serpentirhabdias species in ball pythons (Python regius). J. Comp. Pathol. 2015, 152, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihalca, A.D. Ticks imported to Europe with exotic reptiles. Vet. Parasitol. 2015, 213, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoder, J.A.; Rausch, B.A.; Jajack, A.J.; Tomko, P.M.; Gribbins, K.M.; Benoit, J.B. Snakes produce kairomones that induce aggregation of unfed larval blacklegged ticks Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae). Int. J. Acarol. 2013, 39, 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M. Parasitisation and localisation of ticks [Acari: Ixodida] on exotic reptiles imported into Poland. Ann. Agr. Env. Med. 2010, 17, 237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, M. The international trade in reptiles (Reptilia)—the cause of the transfer of exotic ticks (Acari: Ixodida) to Poland. Vet. Parasitol. 2010, 169, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, M.A.O.; Bertelsen, M.F.; Wang, T.; Pedersen, M.; Lauridsen, H.; Heegaard, S. Unilateral microphthalmia or anophthalmia in eight pythons (Pythonidae). Vet. Ophthalmol. 2015, 18, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, R.A.; Schumacher, J.P.; Rathore, K.; Newkirk, K.M.; Cole, G.; Seibert, R.; Cekanova, M. Evaluation of the role of the cyclooxygenase signaling pathway during inflammation in skin and muscle tissues of ball pythons (Python regius). Am. J. Vet. Res. 2016, 77, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilliger, L.H.; Morel, D.; Bonwitt, J.H.; Marquis, O. Cheyletus eruditus (Taurrus®): An effective candidate for the biological control of the snake mite (Ophionyssus natricis). J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2013, 44, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, G.L.; Lux, C.N.; Schumacher, J.P.; Seibert, R.L.; Sadler, R.A.; Henderson, A.L.; Odoi, A.; Newkirk, K.M. Effect of laser treatment on first-intention incisional wound healing in ball pythons (Python regius). Am. J. Vet. Res. 2015, 76, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zancolli, G.; Mahsberg, D.; Sickel, W.; Keller, A. Reptiles as reservoirs of bacterial infections: real threat or methodological bias? Microb. Ecol. 2015, 70, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Cieniuch, S.; Stańczak, J.; Siuda, K. Detection of Anaplasmaphagocytophilum in Amblyomma flavomaculatum ticks (Acari: Ixodidae) collected from lizard Varanus exanthematicus imported to Poland. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2010, 51, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busse, H.J.; Huptas, C.; Baumgardt, S.; Loncaric, I.; Spergser, J.; Scherer, S.; Wenning, M.; Kämpfer, P. Proposal of Lysobacter pythonis sp. nov. isolated from royal pythons (Python regius). Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 42, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, D.A.; Wellehan, J.F.; Isaza, R. Saccular lung cannulation in a ball python (Python regius) to treat a tracheal obstruction. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2009, 40, 214–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galecki, R.; Sokol, R.; Dudek, A. Tongue worm (Pentastomida) infection in ball pythons (Python regius)-a case report. Ann. Parasitol. 2016, 62, 363–365. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ayinmode, A.B.; Adedokun, A.O.; Aina, A.; Taiwo, V. The zoonotic implications of pentastomiasis in the royal python (Python regius). Ghana Med. J. 2010, 44, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucio-Forster, A.; Liotta, J.L.; Rishniw, M.; Bowman, D.D. Serpentirhabdias dubielzigi n. sp.(Nematoda: Rhabdiasidae) from Captive-Bred Ball Pythons, Python regius (Serpentes: Pythonidae) in the United States. Comp. Parasitol. 2015, 82, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halla, U.; Korbel, R.; Mutschmann, F.; Rinder, M. Blood parasites in reptiles imported to Germany. Parasitol. Res. 2014, 113, 4587–4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé, B.; Maia, J.P.; Salvi, D.; Brito, J.C.; Carretero, M.A.; Perera, A.; Meimberg, H.; Harris, D.J. Patterns of genetic diversity in Hepatozoon spp. infecting snakes from North Africa and the Mediterranean Basin. Syst. Parasitol. 2014, 87, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haklová, B.; Majláthová, V.; Majláth, I.; Harris, D.J.; Petrilla, V.; Litschka-Koen, T.; Oros, M.; Peťko, B. Phylogenetic relationship of Hepatozoon blood parasites found in snakes from Africa, America and Asia. Parasitology 2014, 141, 389–398. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, H.; Takano, A.; Kawabata, H.; Une, Y.; Watanabe, H.; Mukhtar, M.M. Trypanosoma cf. varani in an imported ball python (Python reginus) from Ghana. J. Parasitol. 2009, 95, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco-Lauth, A.M.; Hartwig, A.E.; Bowen, R.A. Reptiles and amphibians as potential reservoir hosts of Chikungunya virus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018, 98, 841–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marton, S.; Ihász, K.; Lengyel, G.; Farkas, S.; Dán, Á.; Paulus, P.; Bányai, K.; Fehér, E. Ubiquiter circovirus sequences raise challenges in laboratory diagnosis: the case of honey bee and bee mite, reptiles, and free-living amoebae. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2015, 62, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L.W.; Fu, A.; Wozniak, E.; Chow, M.; Duke, D.G.; Green, L.; Kelley, K.; Hernandez, J.A.; Jacobson, E.R. Immunohistochemical detection of a unique protein within cells of snakes having inclusion body disease, a world-wide disease seen in members of the families Boidae and Pythonidae. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keilwerth, M.; Buehler, I.; Hoffmann, R.; Soliman, H.; El-Matbouli, M. Inclusion Body Disease (IBD of Boids) a haematological, histological and electron microscopical study. Berl. Munch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 2012, 125, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pees, M.; Schmidt, V.; Marschang, R.E.; Heckers, K.O.; Krautwald-Junghanns, M.E. Prevalence of viral infections in captive collections of boid snakes in Germany. Vet. Rec. 2010, 166, 422–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschang, R.E.; Papp, T.; Frost, J.W. Comparison of paramyxovirus isolates from snakes, lizards and a tortoise. Virus Res. 2009, 144, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Green, J.; Coulthard, E.; Megson, D.; Norrey, J.; Norrey, L.; Rowntree, J.K.; Bates, J.; Dharmpaul, B.; Auliya, M.; D’Cruze, N. Blind Trading: A Literature Review of Research Addressing the Welfare of Ball Pythons in the Exotic Pet Trade. Animals 2020, 10, 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10020193

Green J, Coulthard E, Megson D, Norrey J, Norrey L, Rowntree JK, Bates J, Dharmpaul B, Auliya M, D’Cruze N. Blind Trading: A Literature Review of Research Addressing the Welfare of Ball Pythons in the Exotic Pet Trade. Animals. 2020; 10(2):193. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10020193

Chicago/Turabian StyleGreen, Jennah, Emma Coulthard, David Megson, John Norrey, Laura Norrey, Jennifer K. Rowntree, Jodie Bates, Becky Dharmpaul, Mark Auliya, and Neil D’Cruze. 2020. "Blind Trading: A Literature Review of Research Addressing the Welfare of Ball Pythons in the Exotic Pet Trade" Animals 10, no. 2: 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10020193

APA StyleGreen, J., Coulthard, E., Megson, D., Norrey, J., Norrey, L., Rowntree, J. K., Bates, J., Dharmpaul, B., Auliya, M., & D’Cruze, N. (2020). Blind Trading: A Literature Review of Research Addressing the Welfare of Ball Pythons in the Exotic Pet Trade. Animals, 10(2), 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10020193