Effects of Dog-Based Animal-Assisted Interventions in Prison Population: A Systematic Review

Abstract

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources and Searches

2.2. Risk of Bias

2.3. Data Extraction

3. Results

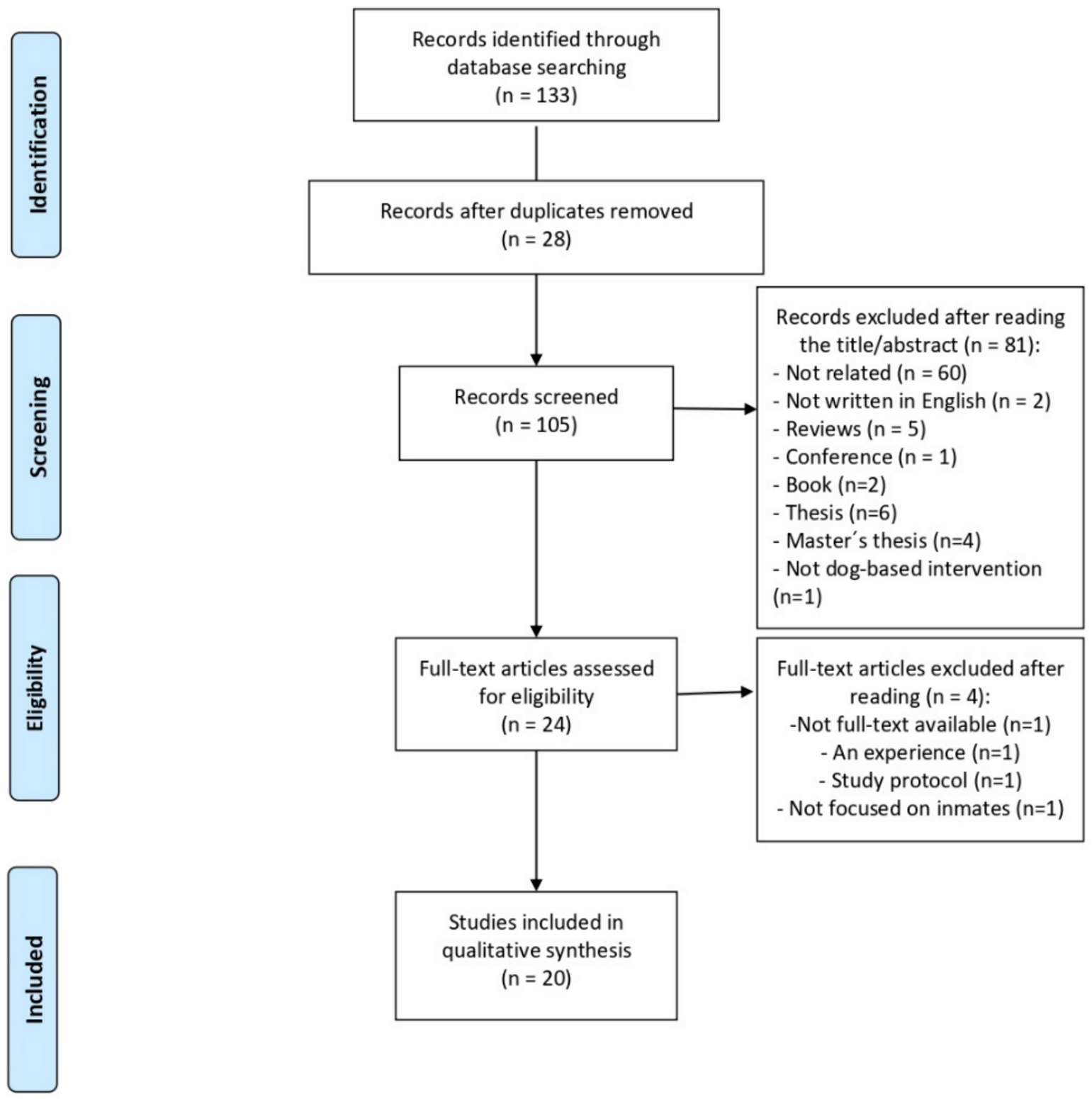

3.1. Article Selection

3.2. Risk of Bias

3.3. Participants

3.4. Study Design

3.5. Intervention

3.6. Comparison Groups

3.7. Outcomes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hockenberry, S.; Puzzanchera, C. Juvenile Court Statistics. 2015. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11212/1194 (accessed on 16 November 2020).

- Lahey, B.B.; Waldman, I.D.; McBurnett, K. Annotation: The development of antisocial behavior: An integrative causal model. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 1999, 40, 669–682. [Google Scholar]

- Goff, A.; Rose, E.; Rose, S.; Purves, D. Does PTSD occur in sentenced prison populations? A systematic literature review. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health CBMH 2007, 17, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leskelä, U.; Rytsälä, H.; Komulainen, E.; Melartin, T.; Sokero, P.; Lestelä-Mielonen, P.; Isometsä, E. The influence of adversity and perceived social support on the outcome of major depressive disorder in subjects with different levels of depressive symptoms. Psychol. Med. 2006, 36, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Armistead, L.; Wierson, M.; Forehand, R.; Frame, C. Psychopathology in incarcerated juvenile delinquents: Does it extend beyond externalizing problems? Adolescence 1992, 27, 309. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, R.J.; Schlosser, S. Emotional responses to peer praise in children with and without a diagnosed externalizing disorder. Merrill Palmer Q. 1994, 40, 60–81. [Google Scholar]

- Wilper, A.P.; Woolhandler, S.; Boyd, J.W.; Lasser, K.E.; McCormick, D.; Bor, D.H.; Himmelstein, D.U. The health and health care of US prisoners: Results of a nationwide survey. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, 666–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, S.; Danesh, J. Serious mental disorder in 23,000 prisoners: A systematic review of 62 surveys. Lancet 2002, 359, 545–550. [Google Scholar]

- Fazel, S.; Hayes, A.J.; Bartellas, K.; Clerici, M.; Trestman, R. Mental health of prisoners: Prevalence, adverse outcomes, and interventions. Lancet Psychiatry 2016, 3, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, J.C.; Mears, D.P.; Bales, W.D.; Stewart, E.A. Does inmate behavior affect post-release offending? Investigating the misconduct-recidivism relationship among youth and adults. Justice Q. 2014, 31, 1044–1073. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier, A.K.; Geller, E.S.; Fortney, E.V. Human-animal interaction in a prison setting: Impact on criminal behavior, treatment progress, and social skills. Behav. Soc. Issues 2007, 16, 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, B.; Meade, B. Assessing the link between exposure to a violent prison context and inmate maladjustment. J. Contemp. Crim. Justice 2016, 32, 328–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furst, G. Animal Programs in Prison: A Comprehensive Assessment; First Forum Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, B.J.; Farrington, D.P. The effects of dog-training programs: Experiences of incarcerated females. Women Crim. Justice 2015, 25, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strimple, E.O. A history of prison inmate-animal interaction programs. Am. Behav. Sci. 2003, 47, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fine, A.H. Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy: Theoretical Foundations and Guidelines for Practice; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Souter, M.A.; Miller, M.D. Do animal-assisted activities effectively treat depression? A meta-analysis. Anthrozoös 2007, 20, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dell, C.; Chalmers, D.; Stobbe, M.; Rohr, B.; Husband, A. Animal-assisted therapy in a Canadian psychiatric prison. Int. J. Prison. Health 2019, 15, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besthorn, F.H.; Saleebey, D. Nature, genetics and the biophilia connection: Exploring linkages with social work values and practice. Adv. Social Work 2003, 4, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa, M.; Kikusui, T.; Onaka, T.; Ohta, M. Dog’s gaze at its owner increases owner’s urinary oxytocin during social interaction. Horm. Behav. 2009, 55, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.M.; Katcher, A.H. Between Pets and People: The Importance of Animal Companionship; Purdue University Press: West Lafayette, IN, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Serpell, J. In the Company of Animals: A Study of Human-Animal Relationships; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Beetz, A.; Uvnäs-Moberg, K.; Julius, H.; Kotrschal, K. Psychosocial and psychophysiological effects of human-animal interactions: The possible role of oxytocin. Front. Psychol. 2012, 3, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amiot, C.E.; Bastian, B. Toward a psychology of human–animal relations. Psychol. Bull. 2015, 141, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odendaal, J.S.J. Animal-assisted therapy—Magic or medicine? J. Psychosom. Res. 2000, 49, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odendaal, J.S.J.; Meintjes, R.A. Neurophysiological correlates of affiliative behaviour between humans and dogs. Vet. J. 2003, 165, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cagna, F.; Fusar-Poli, L.; Damiani, S.; Rocchetti, M.; Giovanna, G.; Mori, A.; Politi, P.; Brondino, N. The role of intranasal oxytocin in anxiety and depressive disorders: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2019, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, E.C.J.; Wallace, J.E.; Pater, R.; Gross, D.P. Evaluating the Relationship between Well-Being and Living with a Dog for People with Chronic Low Back Pain: A Feasibility Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann, E.; Katcher, A.H.; Thomas, S.A.; Lynch, J.J.; Messent, P.R. Social interaction and blood pressure: Influence of animal companions. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1983, 171, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viau, R.; Arsenault-Lapierre, G.; Fecteau, S.; Champagne, N.; Walker, C.-D.; Lupien, S. Effect of service dogs on salivary cortisol secretion in autistic children. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2010, 35, 1187–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, L. Construct validity of animal-assisted therapy and activities: How important is the animal in AAT? Anthrozoös 2012, 25, s139–s151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, E.; Combs, K.M.; Gandenberger, J.; Tedeschi, P.; Morris, K.N. Measuring the Psychological Impacts of Prison-Based Dog Training Programs and In-Prison Outcomes for Inmates. Prison J. 2020, 100, 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamioka, H.; Okada, S.; Tsutani, K.; Park, H.; Okuizumi, H.; Handa, S.; Oshio, T.; Park, S.-J.; Kitayuguchi, J.; Abe, T. Effectiveness of animal-assisted therapy: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Complementary Ther. Med. 2014, 22, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furst, G. Prison-based animal programs: A national survey. Prison J. 2006, 86, 407–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, J. Pet. Facilitated Therapy in Correctional Institutions; Correctional Services of Canada by Office of the Deputy Commissioner for Women: Ottawa, QC, Canada, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson-Taylor, K.; Blanchette, K. Results of an Evaluation of the Pawsitive Directions Canine Program at Nova Institution for Women; Correctional Service Canada, Research Branch: Ottawa, QC, Canada, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K. Perspectives of youth in an animal-centered correctional vocational program: A qualitative evaluation of Project Pooch. Unpublished Research Monograph 2007, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Currie, N.S. A Case Study of Incarcerated Males Participating in a Canine Training Program. Ph.D. Thesis, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Koda, N.; Miyaji, Y.; Kuniyoshi, M.; Adachi, Y.; Watababe, G.; Miyaji, C.; Yamada, K. Effects of a dog-assisted program in a Japanese prison. Asian J. Criminol. 2015, 10, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germain, S.M.; Wilkie, K.D.; Milbourne, V.M.K.; Theule, J. Animal-assisted psychotherapy and trauma: A meta-analysis. Anthrozoös 2018, 31, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, B.J.; Farrington, D.P. The effectiveness of dog-training programs in prison: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Prison J. 2016, 96, 854–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, C.E.; Fonner, V.A.; Armstrong, K.A.; Denison, J.A.; Yeh, P.T.; O’Reilly, K.R.; Sweat, M.D. The evidence project risk of bias tool: Assessing study rigor for both randomized and non-randomized intervention studies. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasperson, R.A. Animal-assisted therapy with female inmates with mental illness: A case example from a pilot program. J. Offender Rehabil. 2010, 49, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seivert, N.P.; Cano, A.; Casey, R.J.; Johnson, A.; May, D.K. Animal assisted therapy for incarcerated youth: A randomized controlled trial. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2018, 22, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syzmanski, T.; Casey, R.J.; Johnson, A.; Cano, A.; Albright, D.; Seivert, N.P. Dog training intervention shows social-cognitive change in the journals of incarcerated youth. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contalbrigo, L.; De Santis, M.; Toson, M.; Montanaro, M.; Farina, L.; Costa, A.; Nava, F.A. The efficacy of dog assisted therapy in detained drug users: A pilot study in an Italian attenuated custody institute. IJERPH 2017, 14, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koda, N.; Watanabe, G.; Miyaji, Y.; Kuniyoshi, M.; Miyaji, C.; Hirata, T. Effects of a dog-assisted intervention assessed by salivary cortisol concentrations in inmates of a Japanese prison. Asian J. Criminol. 2016, 11, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, L.F.; Wilkerson, S.; Ellmo, F.; Skirius, M. Impact of Animal Assisted Therapy on Anxiety Levels among Mentally Ill Female Inmates. J. Creat. Ment. Health 2020, 15, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasperson, R.A. An animal-assisted therapy intervention with female inmates. Anthrozoös 2013, 26, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collica-Cox, K.; Furst, G. Implementing Successful Jail-Based Programming for Women: A Case Study of Planning Parenting, Prison & Pups—Waiting to ‘Let the Dogs In’. J. Prison Educ. Reentry 2019, 5, 101–119. [Google Scholar]

- Minke, L.K. Normalization, social bonding, and emotional support—A dog’s effect within a prison workshop for women. Anthrozoös 2017, 30, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minton, C.A.; Perez, P.R.; Miller, K. Voices from behind prison walls: The impact of training service dogs on women in prison. Soc. Anim. 2015, 23, 484–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz-Lomelin, A.; Nordberg, A. Assessing the impact of an animal-assisted intervention for jail inmates. J. Offender Rehabil. 2020, 59, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.P. A rescue dog program in two maximum-security prisons: A qualitative study. J. Offender Rehabil. 2019, 58, 305–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, M.E.; Davis, R.G.; Shutt, S.R. Dog training programs in Pennsylvania’s Department of Corrections: Perceived effectiveness for inmates and staff. Soc. Anim. 2017, 25, 475–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetina, B.U.; Krouzecky, C.; Emmett, L.; Klaps, A.; Ruck, N.; Kovacovsky, Z.; Bunina, A.; Aden, J. Differences between Female and Male Inmates in Animal Assisted Therapy (AAT) in Austria: Do We Need Treatment Programs Specific to the Needs of Females in AAT? Animals 2020, 10, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, R.J.; Buchanan-Smith, H.M.; McIvor, G.; Vick, S.-J. “You think you’re helping them, but they’re helping you too”: Experiences of Scottish male young offenders participating in a dog training program. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, H.P.; Smith, H. A qualitative assessment of a dog program for youth offenders in an adult prison. Public Health Nurs. 2019, 36, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braithwaite, R.L.; Treadwell, H.M.; Arriola, K.R.J. Health disparities and incarcerated women: A population ignored. Am. J. Public Health 2005, 95, 1679–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiles, W.B.; Barkham, M.; Wheeler, S. Duration of psychological therapy: Relation to recovery and improvement rates in UK routine practice. Br. J. Psychiatry 2015, 207, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boerema, A.M.; Cuijpers, P.; Beekman, A.T.F.; Hellenthal, A.; Voorrips, L.; van Straten, A. Is duration of psychological treatment for depression related to return into treatment? Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2016, 51, 1495–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SAMHSA. Treatment Episode Data Set (TENDS), State Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services (2004–2014); Department of Health and Human Services; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2014.

- Kazdin, A.E. Methodological standards and strategies for establishing the evidence base of animal-assisted therapies. In Handbook on Animal-Assisted Therapy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 519–546. [Google Scholar]

| Study | Cohort | Control or Comparison Group | Pre/Post Intervention Data | Random Assignment of Participants to Intervention | Random Selection of Participants for Assessment | Follow-Up Rate of 80% or More | Comparison Groups Equivalent on Sociodemographics | Comparison Groups Equivalentat Baseline On Disclosure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antonio (2017) |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Collica-Cox (2018) |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Contalbringo (2017) |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Cooke (2015) |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Dell (2019) |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Flynn (2019) |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Holman (2020) |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Jasperson (2010) |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Jasperson (2015) |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Koda (2015) |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Koda (2016) |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Kunz-Lomelin (2019) |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Leonardi (2017) |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Minke (2017) |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Minton (2015) |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Seivert (2016) |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Smith (2019) |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Smith and Smith (2019) |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Stetina (2020) |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Syzmanski (2018) |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

| Study/Year | Participants | Sample Size (N) | Age (SD) | Study Design | Control Group Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antonio (2017) | Female and male inmates and staff | 62 | 45.36 (9.29) 43.85 (11.69) | Observational (Quantitative) | None |

| Collica-Cox (2018) | Female inmates | 10 | NR | Non-RCT (Qualitative) | Parenting, prison, and pups program without animal-assisted intervention |

| Contalbringo (2017) | Drug-addicted male inmates | 22 | EG: 35.5(13.83) CG: 42.9 (9.1) | Non-RCT (Quantitative) | Standard rehabilitation program |

| Cooke (2015) | Female inmates (Adults and young) with problems in psychological and emotional health | 20 12 AI 8 YI | AI: 38.36 YI: 14–19 | Observational (Qualitative) | None |

| Dell (2019) | Male and female inmates in psychiatric prison | 3 1 F 2 M | 48 | Observational (Quantitative) | None |

| Flynn (2019) | Male and female inmates | 229 | EG: 39.4 (13.0) CG: 40.9 (11.0) | Non-RCT (Quantitative) | Passive control group. They did not participate in the program |

| Holman (2020) | Female inmates in mental health prison unit | 6 | 31 (7) | Observational (Quantitative) | None |

| Jasperson (2010) | Female inmates with mental illness | 5 | 26–42 | Observational (Qualitative) | None |

| Jasperson (2013) | Female inmates | 81 | 36 | RCT (Quantitative) | Psycho-education and therapeutic intervention without dog |

| Koda (2015) | Male inmates with developmental disorders | 72 | 26–60 | Observational (Quantitative) | None |

| Koda (2016) | Male inmates with psychiatric or/and developmental disorders | 73 | 26–60 | Observational (Quantitative) | None |

| Kunz-Lomelin (2019) | Male inmates | 17 | 19–58 | Observational (Quantitative) | None |

| Leonardi (2017) | Young offenders | 66 | 16–21 | Observational (Qualitative) | None |

| Minke (2017) | Female inmates | 12 | 39 | Observational (Qualitative) | None |

| Minton (2015) | Female inmates (multi-level security prison) | 30 | 50.23 | Observational (Qualitative) | None |

| Seivert (2016) | Young inmates | 117 | 15.7 (0.9) | RCT (Quantitative) | Animal education component and interaction component (Not engaged in dog training and were not assigned to any specific dog) |

| Smith (2019) | Male inmates (maximum-security prisons) | 285 | NR | Observational (Qualitative) | None |

| Smith and Smith (2019) | Young inmates (in adult prison) | 31 | 21 | Observational (Qualitative) | None |

| Stetina (2020) | Female and male inmates | 81 50 M 31 F | 29.3 (7.24) | Observational (Quantitative) | None |

| Syzmanski (2018) | Young inmates | 73 43 EG 30 CG | NR | RCT (Quantitative) | Only walking dogs without teaching them |

| Study/Year | Intervention Duration (Weeks) | Session Duration (Minute) | Weekly Frequency (Days) | Activities Included in Session |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antonio (2017) | -- | -- | -- | Dog training program. |

| Collica-Cox (2019) | 8 | 120 | 2 | The classes included Orientation and Parenting Styles; Effective Speaking; Effective Listening; Effective Problem Solving; Bonding Through Play and Reading; The Parent’s Job and The Child’s Job; Directions and Encouragement; Rules, Rewards and Consequences; Time Out with Back-Up Privilege Removal (non-violent discipline); Going Home To Your Children; Stress Management and Meditation; Healthy Adult Relationships; and CPR, First Aid, and AED certification for adults, children, and infants. The dogs will serve as emotional support during the class when difficult topics are discussed and the dogs will be incorporated into each lesson and serve as avatars/surrogates as women practice some of their skills. The therapy dogs will be available for the children and family members during the reunification/graduation day. |

| Contalbringo et al. (2017) | 26 | 60 | 1 | Experimental group is involved in dog-assisted therapy session, while control group is only part of standard rehabilitation program. Participants had to experience the interaction with the dog and they were involved in management and performance activities. |

| Cooke (2015) | 8 | -- | -- | Rehabilitation and educational program where participants have to train and care for shelter dogs. |

| Dell (2019) | 26 | 30 | -- | Participants are part of animal-assisted therapy where it is intended to work human-animal bond. |

| Flynn (2019) | -- | -- | -- | There are inmates who are part of dog training program, while there are a control group who are not part of dog training program. |

| Holman (2020) | 8 | 30 | 1 | Participants try to do clicker training exercise individually with the dog. |

| Jasperson (2010) | 4 or 8 | 60 | 2 or 1 | The treatment group implemented the use of a dog in order to facilitate the educational and therapeutic goals. In general, sessions were focused on the development of social skills, coping skills, and self-awareness. Each week, treatment group would sit in a circle on the floor and the dog would remain in the center of the circle. So, human–animal interaction was based on group member or animal initiative. |

| Jasperson (2015) | 8 | 60 | 1 | The group focused on personal safety, developing trust, being trustworthy, responsibility, understanding emotions, expressing emotions in a healthy manner, and learning new behaviors. Each week, group members sat in a circle on the floor and the dog remained in the center of the circle. Member or animal initiative prompted human–animal interaction. |

| Koda (2015) | 12 | 70 | 1 | The program was semi-structured with six themes, namely dog walking, dog obedience training, dog health check, dog massage, dog health care, and games with dogs. Each theme was repeated twice in successive weeks with different visitation dog–handler pairs. |

| Koda (2016) | 12 | 70 | 1 | The program was semi-structured and consisted of six activities, namely dog walking, dog obedience training, dog health check, dog massage, dog healthcare, and playing games with dogs. Each activity was repeated twice, in two successive weeks with different visiting dog–handler pairs. |

| Kunz-Lomelin (2019) | 5 | -- | -- | Participants are involved in a dog training course in which dogs receive Canine Good Citizenship. |

| Leonardi (2017) | 8 | -- | 3 | Maximum 10 young men participating in each session. Participants learns how to train and care for the dogs, so they design training plans and use positive reinforcement methods to achieve their training goals. |

| Minke (2017) | -- | -- | -- | Participants are involved in activities such as walking dog, cooking and dining, manufacturing key-hangers, and engaging in hobbies. |

| Minton (2015) | 26–208 | -- | -- | Dog training program in which women participated as dog trainers or assistants for the prison pup program. |

| Seivert(2016) | 10 | 120 | 2 | Sessions included a didactic 1 h animal education component and 1 h dog interaction component. The intervention group, in the interaction component, is involved in experiential learning in the form of positive dog training. While the control group do not engage in dog training and are not assigned to any specific dog. |

| Smith (2019) | -- | -- | -- | Participants are involved in a dog-training program in which inmates are part of a program with rescue dogs. |

| Smith and Smith (2019) | -- | -- | -- | Participants are involved in a dog-training program in which inmates are part of a program with rescue dogs. |

| Stetina (2020) | 10 | 60 | 1 | Dog-assisted group therapy is involved in competence and communication training that aims to enhance the social and emotional skills of the participants learning through interaction with the dog based on social and emotional skills that humans can learn from canines or socio-emotional interactions. |

| Syzmanski (2018) | 10 | 120 | 2 | Experimental group was learning to train dogs, while control group was walking the dogs. They also had classroom-based didactic sessions each week that focused on information about dog care, dog behavior, and humane treatment. |

| Authors | Instruments | Outcome Measure | EG Baseline | EG after Treatment | CG Baseline | CG after Treatment | Reported Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized Controlled Trials | |||||||

| Jasperson (2015) | Questionnaire (OQ) | -Social Role | 14.33 (4.27) | 12.65(3.80) | 12.25 (4.39) | 11.57 (4.82) | WG (EG) |

| -Symptom distress | 45.47 (11.77) | 37.16 (13.98) | 39.56 (14.31) | 33.58 (13.06) | WG (EG) | ||

| -Interpersonal relationships | 21.40 (4.57) | 19.91 (6.37) | 19.82 (5.12) | 17.98 (6.30) | WG (EG) | ||

| Seivert (2016) | TRFYSR | -Staff report internalizing | 56.76 (9.09) | 58.36 (9.50) | 55.72 (9.18) | 55.84 (9.62) | WG (EG/CG) |

| -Youth report internalizing | 55.43 (10.74) | 56.33 (11.04) | 53.89(11.09) | 55.07 (10.86) | WG (EG/CG) | ||

| -Empathic concern | 17.74 (5.54) | 17.67 (5.42) | 16.85 (5.50) | 18.43 (4.63) | WG (EG/CG) | ||

| -Perspective taking | 14.30 (5.92) | 14.47 (5.58) | 14.93 (5.12) | 16.25 (5.35) | = | ||

| Syzmanski (2018) | Review and medical chart | -Future orientation | NR | 6.13 (2.91) | NR | 4.33 (3.15) | = |

| -Cognitive growth | NR | 8.05 (3.93) | NR | 4.70 (2.52) | = | ||

| -Self-awareness | NR | 3.14 (1.27) | NR | 3.04 (1.90) | = | ||

| -Attachment | NR | 6.79 (5.29) | NR | 3.13 (3.10) | = | ||

| -Attitude toward program | NR | 3.12 (2.63) | NR | 1.08 (0.95) | = | ||

| -Positivity of emotion | NR | 4.03 (1.21) | NR | 2.97 (2.64) | = | ||

| Non-Randomized Controlled Trial | |||||||

| Contalbringo (2017) | SCL-90-R | -Somatization | 0.98 (0.89) | 0.21 (0.24) | 1.17 (1.30) | 0.65 (0.74) | WG (EG) |

| -Obsessive-compulsive symptoms | 1.07 (0.61) | 0.46 (0.29) | 1.37 (1.05) | 0.83 (0.53) | WG (EG) | ||

| -Interpersonal sensitivity | 0.60 (0.59) | 0.23 (0.24) | 0.70 (0.51) | 0.52 (0.55) | = | ||

| -Depression | 1.34 (0.84) | 0.45 (0.32) | 1.10 (0.77) | 0.83 (0.48) | WG (EG)/BG | ||

| -Anxiety | 1.39 (0.95) | 0.44 (0.35) | 1.07 (0.83) | 0.73 (0.41) | WG (EG) | ||

| -Hostility | 0.57 (0.58) | 0.43 (0.36) | 0.67 (0.75) | 0.53 (0.54) | = | ||

| -Phobic anxiety | 0.46 (0.55) | 0.06 (0.07) | 0.82 (1.40) | 0.35 (0.51) | =/BG | ||

| -Paranoid ideation | 1.17 (0.72) | 0.54 (0.49) | 0.86 (0.74) | 0.83 (0.59) | WG (EG) | ||

| -Psychoticism | 0.73 (0.62) | 0.19 (0.16) | 0.84 (0.77) | 0.66 (0.41) | WG (EG) | ||

| -Sleep disorders | 1.78 (0.53) | 0.63 (0.59) | 1.89 (1.47) | 1.00 (1.02) | WG(EG/CG)/BG | ||

| -Global severity index | 1.01 (0.54) | 0.35 (0.19) | 1.00 (0.82) | 0.67 (0.43) | WG (EG) | ||

| Flynn (2019) | Survey | -Infraction rate | 0.68 | 0.34 | 0.54 | 1.01 | WG (EG) |

| -Self-efficacy | NR | 3.23 (0.47) | NR | 3.15 (0.55) | = | ||

| -State anxiety | NR | 1.54 (0.48) | NR | 1.70 (0.61) | BG | ||

| -Trait anxiety | NR | 1.91 (0.49) | NR | 1.98 (0.56) | = | ||

| -Empathy | NR | 4.00 (0.75) | NR | 3.81 (0.88) | = | ||

| -Perspective taking | NR | 3.42 (0.94) | NR | 3.42 (0.93) | = | ||

| -Fantasy | NR | 3.09 (1.00) | NR | 3.09 (0.96) | = | ||

| Observational | |||||||

| Antonio (2017) | SAQ | -Reduced recidivism | NR | 6.88 (2.36) M | NR | 7.80 (2.37) F | BG |

| -Non-violent incidents in prison | NR | 3.76 (0.98) M | NR | 4.09 (1.17) F | BG | ||

| -Violent incidents in prison | NR | 4.32 (0.79) M | NR | 4.50 (0.72) F | = | ||

| -Cooperative with correctional staff | NR | 4.26 (0.73) M | NR | 4.44 (0.90) F | = | ||

| -Improved morale | NR | 4.24 (0.82) M | NR | 4.39 (0.91) F | = | ||

| -Brings all inmates together as a community | NR | 3.67 (0.98) M | NR | 4.10 (0.86) F | BG | ||

| -Provides inmates with marketable skills | NR | 4.26 (0.89) M | NR | 4.24 (0.88) F | = | ||

| -Positive interactions with other inmates | NR | 4.18 (0.75) M | NR | 4.39 (0.61) F | = | ||

| Dell (2019) | Questionnaire | -Emotional state | 3.3 (0.66) | 4.8 (0.17) | NR | NR | WG (EG) |

| Holman (2020) | Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7) | -Levels of anxiety | 16.16 (1.04) | 4.33 (4.04) | NR | NR | = |

| Koda (2015) | Questionnaire(PGFSME) | -Tension | 1.65 (1.10) | 1.16 (1.20) | NR | NR | WG (EG) |

| -Depression | 1.46 (1.02) | 1.14 (1.10) | NR | NR | = | ||

| -Irritation | 1.22 (1.01) | 1.09 (1.13) | NR | NR | = | ||

| -Vigor | 1.91 (1.00) | 2.12 (1.22) | NR | NR | = | ||

| -Fatigue | 1.35 (0.93) | 1.25 (1.11) | NR | NR | = | ||

| -Distraction | 1.49 (0.90) | 1.22 (1.11) | NR | NR | = | ||

| -Anxiety | 1.37 (1.04) | 1.18 (1.16) | NR | NR | = | ||

| Koda (2016) | Monitoring salivary cortisol | -Cortisol level | Psychiatric disorders | NR | NR | NR | WG |

| Development disorders | NR | NR | NR | = | |||

| Psychiatric and development disorders | NR | NR | NR | = | |||

| Kunz-Lomelin (2019) | CES-D | -Depression | 36.94 (11.62) | 32.18 (12.50) | NR | NR | = |

| GAD-7 | -Anxiety | 6.59 (5.81) | 5.53 (5.94) | NR | NR | = | |

| RS-E | -Self esteem | 17.76 (6.77) | 17.41 (6.65) | NR | NR | = | |

| PCL-C | -PTSD | 36.24 (14.42) | 27.23 (10.49) | NR | NR | WG (EG) | |

| UCLA | -Loneliness scale | 49.27 (8.63) | 42.55 (14.34) | NR | NR | = | |

| RS | -Brief resiliency scale | 3.82 (1.03) | 4.10 (0.91) | NR | NR | = | |

| Stetina (2020) | SEE | -Accept own emotion | 22.30 (3.56) F | 23.23 (2.69) F | 21.46 (4.69) M | 24.70 (3.8) M | WG (CG)/BG |

| -Emotional flooding | 21.93 (3.91) F | 20.22 (3.81) F | 21.36 (5.84) M | 19.43 (5.03) | WG (ET/CG) | ||

| -Lack of emotions | 13.35 (2.81) F | 13.29 (2.28) F | 13.82 (3.97) M | 12.20 (3.32) M | WG (CG)/BG | ||

| -Somatic representation | 24.77 (6.49) F | 27.03 (4.78) F | 25.20 (5.98) M | 26.30 (5.45) M | = | ||

| -Imaginative representation | 17.90 (4.64) F | 17.32 (4.93) F | 16.40 (4.82) M | 16.98 (4.68) M | = | ||

| -Emotional regulation | 12.16 (3.01) F | 12.80 (2.7) F | 13.30 (3.11) M | 15.66 (2.37) M | WG (CG)/BG | ||

| -Self-control | 20.83 (3.66) F | 21.74 (4.48) F | 19.54 (4.36) M | 22.64 (3.82) M | WG (CG)/BG | ||

| EMI-B | -Anxious vs. free from fear | 64.44 (9.48) F | 65.11 (6.86) F | 57.61 (12.97) M | 49.16 (12.38) M | WG (CG)/BG | |

| -Depressive vs. happy | 29.78 (4.37) F | 28.22 (4.39) F | 29.78 (8.04) M | 22.00 (7.27) M | WG (CG)/BG | ||

| -Tired vs. dynamic | 29.56 (4.13) F | 30.00 (2.03) F | 29.00 (7.65) M | 24.36 (6.84) M | WG (CG)/BG | ||

| -Aggressive vs. calm | 26.78 (5.01) F | 29.22 (2.87) F | 26.97 (7.71) M | 22.63 (6.81) M | WG (CG)/BG | ||

| -Inhibited vs. spontaneous | 32.11 (5.67) F | 32.44 (3.15) F | 29.86 (6.24) M | 27.08 (7.02) M | WG (CG) | ||

| -Lonely vs. secure | 30.67 (3.75) F | 29.11 (2.37) F | 30.50 (6.70) M | 26.52 (4.99) M | WG (EG/CG) | ||

| -Imbalanced feeling vs. well being | 50.56 (11.12) F | 49.33 (14.4) F | 57.80 (14.5) M | 45.36 (13.73) M | WG (CG)/BG | ||

| SDQ-III | -Math | 46.22 (10.86) F | 44.32 (15.8) F | 43.49 (17.45) M | 47.79 (14.82) M | WG (CG)/BG | |

| -Verbal | 43.45 (10.65) F | 55.74 (10.85) F | 53.67 (11.01) M | 59.45 (10.79) M | WG EG/CG)/BG | ||

| -Academic | 46.29 (10.36) F | 48.03 (12.48) F | 45.79 (14.00) M | 53.75 (15.19) M | WG (CG)/BG | ||

| -Problem solving | 48.64 (11.31) F | 56.77 (7.12) F | 51.93 (10.96) M | 64.26 (8.76) M | WG (EG/CG) | ||

| -Physical ability | 44.48 (9.19) F | 51.32 (11.73) F | 51.83 (15.38) M | 53.73 (14.34) M | WG (EG)/BG | ||

| -Same sex peer relations | 38.22 (7.48) F | 52.54 (12.16) F | 52.00 (10.77) M | 58.97 (10.38) M | WG EG/CG)/BG | ||

| -Opposite sex peer relations | 41.03 (16.15) F | 56.35 (7.03) F | 53.42 (10.67) M | 56.95 (11.39) M | WG EG/CG)/BG | ||

| -Parent relation | 39.19 (7.91) F | 44.58 (15.47) F | 46.97 (15.36) M | 48.28 (16.08) M | = | ||

| -Spiritual values/religion | 57.22 (8.89) F | 45.29 (12.54) F | 49.81 (16.28) M | 50.53 (20.33) M | WG (EG)/BG | ||

| -Honesty/trustworthiness | 49.61 (11.89) F | 68.32 (12.06) F | 66.4 (9.99) M | 74.36 (8.14) M | WG EG/CG)/BG | ||

| -Emotional stability | 51.25 (13.67) F | 50.19 (12.24) F | 51.95 (12.64) M | 63.36 (2.24) M | WG (CG)/BG | ||

| -General esteem | 54.19 (10.69) F | 69.93 (11.41) F | 66.08 (14.79) M | 80.18 (10.71) M | WG (EG/CG) | ||

| -Physical appearance | 43.00 (11.01) F | 41.45 (5.58) F | 49.89 (11.84) M | 51.53 (10.35) M | = | ||

| Authors | Instrument | Outcome Measures | EG Results | CG Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Randomized Controlled Trial | ||||

| Collica-Cox (2018) | Interview (DASS21) | Levels of stress | NR | −Stress, depression, and parental stress |

| Anxiety | ||||

| Depression | ||||

| Self-esteem | +Self-esteem | |||

| Observational | ||||

| Cooke (2015) | Interview (Psychometric test) | Psychological and emotional Health | +Motherhood | NR |

| Motherhood | +Transferable skills | NR | ||

| Transferable skills | +Security | NR | ||

| Security | +Trust | NR | ||

| Trust | +Serving time | NR | ||

| Serving time | +Social competence | NR | ||

| +Interpersonal | NR | |||

| dynamics | ||||

| Jasperson (2010) | Report GM and T’S | Anxiety | −Anxiety | NR |

| Depressive symptoms | −Depressive symptoms | NR | ||

| Self-awareness | +Self-awareness | NR | ||

| Observation (MHP) | Social isolation | −Social isolation | NR | |

| Pro-social behaviors | +Prosocial behaviors | NR | ||

| Leonardi (2017) | Semi-structured interviews | −Dogs | +Educational engagement | NR |

| −Positive effects | +Developing employability skills | NR | ||

| −Motivation | +Enhancing well-being | NR | ||

| −Charitable purpose | ||||

| −Self-efficacy | ||||

| −Improved skills | ||||

| −Social impact | ||||

| −Impulsivity | ||||

| −Emotional management | ||||

| Minke (2017) | Interview | −Social relations | +The prison atmosphere and emotional support was better after treatment | NR |

| −Emotional support | +Dog calm them and they defined prison as a “safe place” | NR | ||

| Observation | −Normalizing the prison setting | |||

| Minton (2015) | Semi-structured interviews | −Physical and emotional health | +Stress was reduced and losing weight | NR |

| −Goal-directed | +Improve their self-concept, ability to reorganize | NR | ||

| Behaviors | +Change their negative self-concept into a positive one | NR | ||

| −Self-concept | +More empathic | NR | ||

| −Empathy and self-control | +Ability to meet people | NR | ||

| −Socialization | ||||

| Smith (2019) | Survey questions | −Symbolism of the rescue dog | +Dog represented unconditional love and care | NR |

| −Universal support and spillover effects | +Dog as strengthening a sense of community in the unit | NR | ||

| −Reinforcement of positive emotions | +Dog produced a stabilizing emotional effect | NR | ||

| −Coping and linkage to the outside world | +Emotional stability | NR | ||

| −Hope and transformation | +Positive emotions and coping | NR | ||

| −Rotating dog handlers | +Participants need to rotate | NR | ||

| Smith and Smith (2019) | Survey questions | −Symbolism of the rescue dog | +Empathy and positive emotions | NR |

| −Positive behaviors and rehabilitation | +Hope and rehabilitative developments | NR | ||

| −A sense of normality | +Gave them a sense of normality and connection to the outside world | NR | ||

| −Universal support | +Increase inmate’s positive viewpoint of dog | NR | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Villafaina-Domínguez, B.; Collado-Mateo, D.; Merellano-Navarro, E.; Villafaina, S. Effects of Dog-Based Animal-Assisted Interventions in Prison Population: A Systematic Review. Animals 2020, 10, 2129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10112129

Villafaina-Domínguez B, Collado-Mateo D, Merellano-Navarro E, Villafaina S. Effects of Dog-Based Animal-Assisted Interventions in Prison Population: A Systematic Review. Animals. 2020; 10(11):2129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10112129

Chicago/Turabian StyleVillafaina-Domínguez, Beatriz, Daniel Collado-Mateo, Eugenio Merellano-Navarro, and Santos Villafaina. 2020. "Effects of Dog-Based Animal-Assisted Interventions in Prison Population: A Systematic Review" Animals 10, no. 11: 2129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10112129

APA StyleVillafaina-Domínguez, B., Collado-Mateo, D., Merellano-Navarro, E., & Villafaina, S. (2020). Effects of Dog-Based Animal-Assisted Interventions in Prison Population: A Systematic Review. Animals, 10(11), 2129. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10112129