The Impact of Targeted Trap–Neuter–Return Efforts in the San Francisco Bay Area

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Location

2.2. Background

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Findings

3.2. Common Modes of Disposition

3.3. Program Impacts

4. Discussion

4.1. Population Size

4.2. Disposition

4.3. Population Dynamics

5. Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berkley, E.P. TNR Past, Present and Future: A History of the Trap-Neuter-Return Movement; Alley Cat Allies: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-97-051942-9. [Google Scholar]

- Humane Society of the United States (HSUS). Managing Community Cats: A Guide for Municipal Leaders. 2020. Available online: https://www.animalsheltering.org/page/managing-community-cats-guide-municipal-leaders (accessed on 8 August 2020).

- Best Friends Animal Society. A Brief History of TNR. Available online: https://resources.bestfriends.org/article/brief-history-tnr (accessed on 27 August 2020).

- Kortis, B.; Richmond, S.; Weiss, M.; Frazier, A.; Needham, J.; McClurg, L.; Senk, L.G. Neighborhood Cats TNR Handbook, 2nd ed.; Neighborhood Cats, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, P.J.; Hamilton, F. Managing free-roaming cats in U.S. cities: An object lesson in public policy and citizen action. J. Urban Aff. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, J.D.; Slater, M.A. A Generalized Population Monitoring Program to Inform the Management of Free-Roaming Cats. Available online: http://www.acc-d.org/docs/default-source/think-tanks/frc-monitoring-revised-nov-2014.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2020).

- Boone, J.D. Better trap-neuter-return for free-roaming cats: Using models and monitoring to improve population management. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2015, 17, 800–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutter, F.B. Evaluation of a Trap-Neuter-Return Management Program for Feral Cat Colonies: Population Dynamics, Home Ranges, and Potentially Zoonotic Diseases. Ph.D. Thesis, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Boone, J.D.; Miller, P.S.; Briggs, J.R.; Benka, V.A.; Lawler, D.F.; Slater, M.; Levy, J.K.; Zawistowkski, S. A Long-Term Lens: Cumulative Impacts of Free-Roaming Cat Management Strategy and Intensity on Preventable Cat Mortalities. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spehar, D.D.; Wolf, P.J. Back to School: An Updated Evaluation of the Effectiveness of a Long-Term Trap-Neuter-Return Program on a University’s Free-Roaming Cat Population. Animals 2019, 9, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spehar, D.D.; Wolf, P.J. A Case Study in Citizen Science: The Effectiveness of a Trap-Neuter-Return Program in a Chicago Neighborhood. Animals 2018, 8, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spehar, D.D.; Wolf, P.J. An Examination of an Iconic Trap-Neuter-Return Program: The Newburyport, Massachusetts Case Study. Animals 2017, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarbrick, H.; Rand, J.; Swarbrick, H.; Rand, J. Application of a Protocol Based on Trap-Neuter-Return (TNR) to Manage Unowned Urban Cats on an Australian University Campus. Animals 2018, 8, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreisler, R.E.; Cornell, H.N.; Levy, J.K. Decrease in Population and Increase in Welfare of Community Cats in a Twenty-Three Year Trap-Neuter-Return Program in Key Largo, FL: The ORCAT Program. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, J.K.; Isaza, N.M.; Scott, K.C. Effect of high-impact targeted trap-neuter-return and adoption of community cats on cat intake to a shelter. Vet. J. 2014, 201, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.L.; Cicirelli, J. Study of the effect on shelter cat intakes and euthanasia from a shelter neuter return project of 10,080 cats from March 2010 to June 2014. PeerJ 2014, 2, e646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spehar, D.D.; Wolf, P.J. Integrated Return-To-Field and Targeted Trap-Neuter-Vaccinate-Return Programs Result in Reductions of Feline Intake and Euthanasia at Six Municipal Animal Shelters. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spehar, D.D.; Wolf, P.J. The Impact of Return-to-Field and Targeted Trap-Neuter-Return on Feline Intake and Euthanasia at a Municipal Animal Shelter in Jefferson County, Kentucky. Animals 2020, 10, 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spehar, D.D.; Wolf, P.J. The Impact of an Integrated Program of Return-to-Field and Targeted Trap-Neuter-Return on Feline Intake and Euthanasia at a Municipal Animal Shelter. Animals 2018, 8, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bissonnette, V.; Lussier, B.; Doize, B.; Arsenault, J. Impact of a trap-neuter-return event on the size of free-roaming cat colonies around barns and stables in Quebec: A randomized controlled trial. Can. J. Vet. Res. 2018, 82, 192–197. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, D.; Clarke, A.L. Trap/Neuter/Release Methods Ineffective in Controlling Domestic Cat “Colonies” on Public Lands. Nat. Areas J. 2003, 23, 247–253. [Google Scholar]

- Natoli, E.; Maragliano, L.; Cariola, G.; Faini, A.; Bonanni, R.; Cafazzo, S.; Fantini, C. Management of feral domestic cats in the urban environment of Rome (Italy). Prev. Vet. Med. 2006, 77, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.S.; Boone, J.D.; Briggs, J.R.; Lawler, D.F.; Levy, J.K.; Nutter, F.B.; Slater, M.; Zawistowski, S. Simulating Free-Roaming Cat Population Management Options in Open Demographic Environments. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e113553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Francisco Bay Trail | San Mateo County & Silicon Valley. Available online: https://www.smccvb.com/things-to-do/outdoor-activities/trails/san-francisco-bay-trail/ (accessed on 5 August 2020).

- About San Francisco Bay | San Francisco Bay Joint Venture. Available online: https://www.sfbayjv.org/about-san-francisco-bay.php (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Pacific Flyway. Available online: https://www.audubon.org/pacific-flyway (accessed on 5 August 2020).

- Maddie’s Fund. Working Cat Programs. Available online: www.maddiesfund.org/working-cats-program.htm (accessed on 16 October 2019).

- Christensen, J. Are Cats the Ultimate Weapon in Public Health? CNN Health. Available online: https://www.cnn.com/2016/07/15/health/cats-chicago-rat-patrol/index.html (accessed on 16 October 2020).

- Levy, J.K.; Gale, D.W.; Gale, L.A. Evaluation of the effect of a long-term trap-neuter-return and adoption program on a free-roaming cat population. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2003, 222, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunther, I.; Raz, T.; Klement, E. Association of neutering with health and welfare of urban free-roaming cat population in Israel, during 2012-2014. Prev. Vet. Med. 2018, 157, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.; Rand, J.; Morton, J. Trap-Neuter-Return Activities in Urban Stray Cat Colonies in Australia. Animals 2017, 7, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APPA. 2017–2018 APPA National Pet Owners Survey; American Pet Products Association: Stamford, CT, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- New, J.C.J.; Kelch, W.J.; Hutchison, J.M.; Salman, M.D.; King, M.; Scarlett, J.M.; Kass, P.H. Birth and death rate estimates of cats and dogs in U.S. households and related factors. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2004, 7, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natoli, E.; Malandrucco, L.; Minati, L.; Verzichi, S.; Perino, R.; Longo, L.; Pontecorvo, F.; Faini, A. Evaluation of Unowned Domestic Cat Management in the Urban Environment of Rome After 30 Years of Implementation of the No-Kill Policy (National and Regional Laws). Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutter, F.B.; Levine, J.F.; Stoskopf, M.K. Reproductive capacity of free-roaming domestic cats and kitten survival rate. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2004, 225, 1399–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoskopf, M.K.; Nutter, F.B. Analyzing approaches to feral cat management—one size does not fit all. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2004, 225, 1361–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Final Disposition | No. of Cats by Category | Total No. of Cats (%) | Duration On-Site * | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Age | Mean ± SD | Median | Range | ||||||

| M | F | Unknown | Kitten | Adult | Unknown | (Years) | (Years) | (Years) | ||

| Remaining | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 9 | – | – |

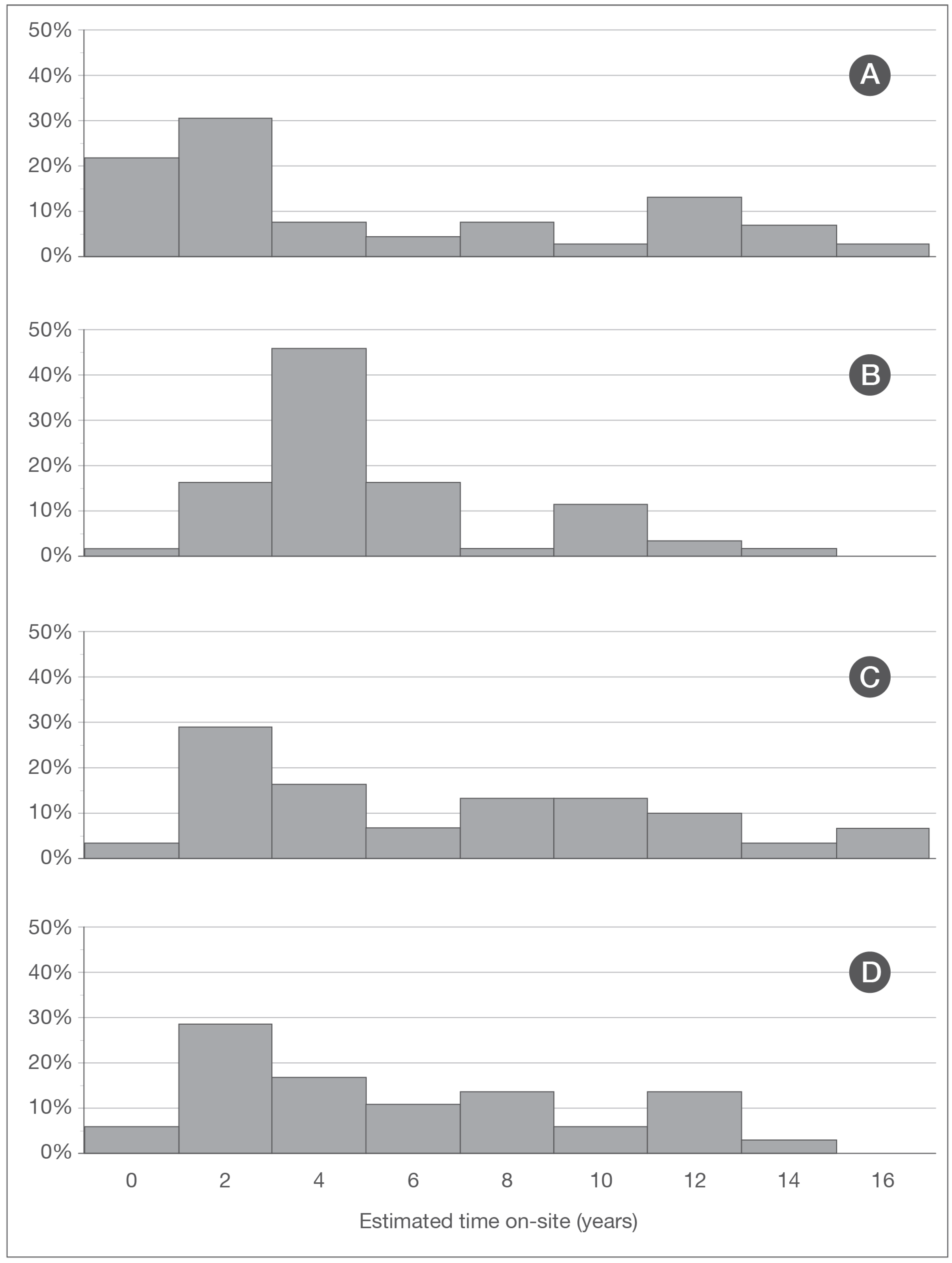

| Adopted | 36 | 50 | 21 | 49 | 44 | 14 | 107 (41%) | 4.3 ± 4.9 | 1.5 | 0–15.6 |

| Foster | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 10 (4%) | 1.7 ± 4.5 | 0 | 0–14.4 |

| Relocated | 3 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 10 (4%) | 7.2 ± 4.9 | 6.8 | 0.3–12.9 |

| Disappeared | 26 | 23 | 11 | 0 | 48 | 12 | 60 (23%) | 4.3 ± 2.9 | 3.6 | 0–13.6 |

| Migrated (off-site) | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 (2%) | 0.3 ± 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1–0.8 |

| Died | 14 | 12 | 5 | 1 | 23 | 7 | 31 (12%) | 5.7 ± 4.6 | 4.8 | 0–14.7 |

| Euthanized | 23 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 27 | 8 | 35 (14%) | 5.0 ± 3.9 | 3.9 | 0–13.1 |

| Total | 107 | 105 | 46 | 54 | 154 | 50 | 258 | 4.5 ± 4.4 | 3.1 | 0–15.6 |

| Program Location | PBC California | University of Central Florida [8] | Newburyport, MA, USA [10] | Key Largo, FL, USA [12] | Chicago, IL, USA [9] | Sydney, Australia [11] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration (years) | 16 | 28 | 17 | 14 | 4–10 | 9 |

| Cat populations | ||||||

| Total managed | 258 | 204 | ~340 | 2529 | 195 | 122 |

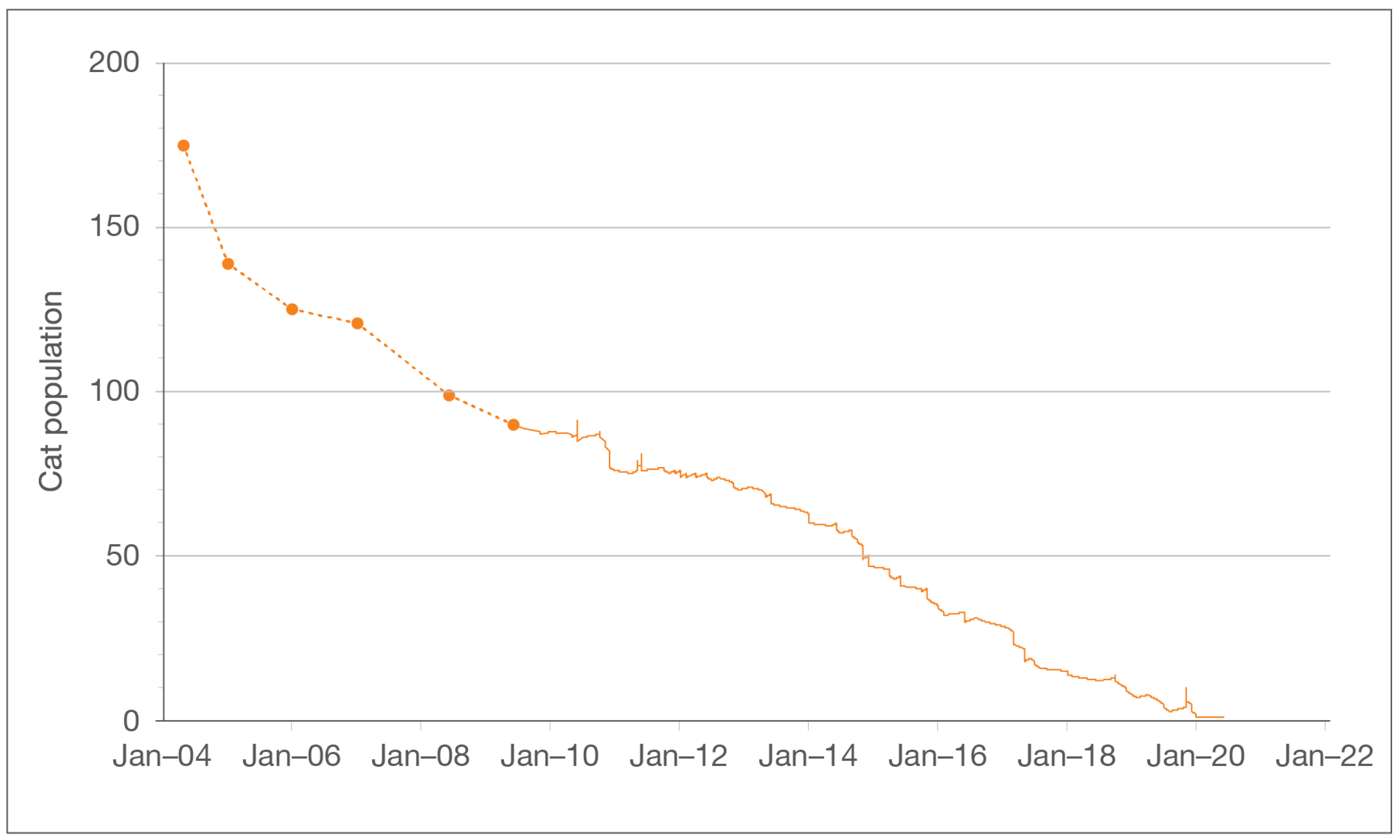

| Initial census | 175 | 68 | ~300 | 455 | 75 † | 69 |

| Remaining cats (no.) | 1 | 10 | 0 | 206 | 44 | 15 |

| (%) | 1 | 5 | 0 | 8 | 23 | 12 |

| Population reduction (%) | 99 | 85 | 100 | 55 | 41 | 78 |

| Colonies eliminated vs. total | 10/11 ‡ | 11/16 | 13/14 ‡ | 41/85 ‡ | 8/20 | NR |

| Modes of disposition | ||||||

| Adoption (%) | 41 | 45 | ~33 | 28 ^ | 30 | 27 |

| Disappeared (%) | 23 | 24 | NR | NR | 34 | 29 |

| Euthanized (%) | 14 | 11 | ~5–10 | 17 ^ | 3 | 17 |

| Died (%) | 12 | 8 | NR | 11 ^ | 7 | 12 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Spehar, D.D.; Wolf, P.J. The Impact of Targeted Trap–Neuter–Return Efforts in the San Francisco Bay Area. Animals 2020, 10, 2089. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10112089

Spehar DD, Wolf PJ. The Impact of Targeted Trap–Neuter–Return Efforts in the San Francisco Bay Area. Animals. 2020; 10(11):2089. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10112089

Chicago/Turabian StyleSpehar, Daniel D., and Peter J. Wolf. 2020. "The Impact of Targeted Trap–Neuter–Return Efforts in the San Francisco Bay Area" Animals 10, no. 11: 2089. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10112089

APA StyleSpehar, D. D., & Wolf, P. J. (2020). The Impact of Targeted Trap–Neuter–Return Efforts in the San Francisco Bay Area. Animals, 10(11), 2089. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10112089