Abstract

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), which caused Coronaviruses Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and a worldwide pandemic, is the seventh human coronavirus that has been cross-transmitted from animals to humans. It can be predicted that with continuous contact between humans and animals, more viruses will spread from animals to humans. Therefore, it is imperative to develop universal coronavirus or pan-coronavirus vaccines or drugs against the next coronavirus pandemic. However, a suitable target is critical for developing pan-coronavirus antivirals against emerging or re-emerging coronaviruses. In this review, we discuss the latest progress of possible targets of pan-coronavirus antiviral strategies for emerging or re-emerging coronaviruses, including targets for pan-coronavirus inhibitors and vaccines, which will provide prospects for the current and future research and treatment of the disease.

1. Introduction

To date, seven coronaviruses have been identified in the human population, including human coronavirus (HCoV)-229E, -OC43, -NL63, and -HKU1, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV), and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), which cross-transmitted from animals (bat, bovine, mouse, or other animals) to human [1]. Moreover, coronaviruses have a wide host spectrum, which was verified in numerous cell lines or animals [2,3]. For example, the SARS-CoV-2 spike could bind ACE2 (Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2) orthologs from 44 domestic animals, pets, livestock, and animals in zoos and aquaria, and initiate viral entry [3]. These results indicate that the potential spillover events of other coronaviruses from animals to humans, especially bat-derived SARS-related coronaviruses (SARSr-CoVs), are increasing, which may cause more pandemics in the future [1,4,5]. Therefore, many researchers suggest developing universal coronavirus vaccines or drugs against the next coronavirus pandemic [4,6]. We fully agree with this proposal, because effective universal vaccines or pan-coronaviruses inhibitors are promising for emerging or re-emerging coronavirus epidemics, which has attracted many groups to participate in designing universal vaccines and inhibitors for decades. However, whether for influenza, AIDS, or COVID-19, it is a challenging task to achieve this goal.

During past decades, many attempts have been made on the universal influenza vaccine, but less progress has been obtained due to three main reasons. First, because of the low conservation of virus antigens in the same viral family, especially key antigenic determinants, few conserved protective cross-reactive antigens have been identified. Second, the continuous mutations of the coronavirus lead to the immune evasion of the viruses and reduce the efficacy of existing vaccines or universal vaccines, which have also been identified in the SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (VOCs), including Alpha (B.1.1.7), Beta (B.1.351), Gamma (P.1), and Delta (B.1.617.2) [7,8,9,10]. Notably, the Delta variant SARS-CoV-2, which is characterized by spike mutations T19R, G142D, Δ157-158, L452R, T478K, D614G, P681R, and D950N, is rapidly outcompeting other VOCs and has become the dominant variant in past months [8,11]. Third, it takes a long time for the vaccine development, clinical trial, and authorized application of the vaccine. Excitingly, with the rapid development of artificial intelligence and vaccine technology, as well as the joint efforts and close cooperation of scientists all over the world, modern vaccinology may be accelerated, and the universal vaccine may be realized in the future.

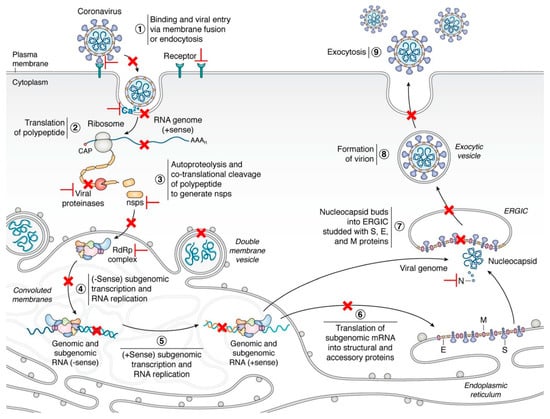

Contrary to the universal vaccine, it is scientifically feasible to develop pan-coronavirus inhibitors based on the genome-scale comprehensive analysis of virus genome and host factors using in silico virtual screening and molecular docking. Until now, numerous drugs or peptides have been identified as promising pan-inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 and other human coronaviruses [12,13,14,15,16,17]. In this review, we discuss the latest progress of possible targets of pan-coronavirus antiviral strategies against emerging or re-emerging coronaviruses (Figure 1), which will provide prospects for the current and future research and treatment of the disease.

Figure 1.

The life cycle of coronaviruses and possible targets for antivirals [18]. Key steps representing attractive antiviral targets are highlighted in red. Inhibitors can target virus fusion (especially the HR1, HR2, or 6-HB of the S2 subunit, Ca2+ channel), viral proteases (Mpro or PLpro), ORF1b and NSPs, replication/transcription complex (including RdRp, NSP14, and 16), viral genomic synthesis, and host factors and pathways (such as regulators of cholesterol metabolism, host proteases, HMGB1, SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex, cyclophilins, and immunophilins). Vaccines are designed by targeting multiple epitopes of the viral RBD, S2 subunit, as well as cross-reactive viral epitopes (in the S and ORF1ab) of B cell, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Reprinted with permission from ref. [18]. Copyright © 2020 Hartenian et al.

4. Conclusions and Perspectives

At present, the COVID-19 pandemic is continuing all over the world, especially the second or third outbreak that occurred in some countries, such as India, Thailand, and Vietnam. As of 2 July, 2021, there were more than 182,319,261 confirmed cases, 3,954,324 deaths, and 2,950,104,812 vaccinations. However, with the frequent contact between humans and animals, and the continuous migration of wild animals, emerging coronaviruses will spillover from animals to humans, and the number of mutant viruses produced by recombination will also increase [1,4,5]. Therefore, it is urgent to design multi-target antiviral strategies to protect against emerging or re-emerging coronaviruses that appear or reappear at present or in the future.

By using high-throughput genome-scale screenings, such as phage display library, CRISPR-based library, and electro-chemiluminescence-based multiplex assay [57,90,103,104], it is hopeful that we will identify conserved cross-reactive epitopes or domains in coronaviruses and host proteins, which can be used for pan-coronavirus antiviral strategies, and design small-molecule drugs and peptides or identify existing pharmaceuticals and herbal medicines specifically targeting coronaviruses infection, such as viral spike protein-receptor binding and fusion, viral polymerase, nonstructural protein, and proteases. Moreover, other antiviral strategies are also required for pan-coronavirus inhibition. For example, the CRISPR-based antiviral strategy reported by Abbott et al. can effectively inhibit 90% of all known coronaviruses by degrading viral RNA with six CRISPR RNAs (crRNAs) targeting conserved viral regions [103]. Notably, vaccines are mainly used for healthy people to prevent infection, while medicines can be used for prevention and treatment. Antivirals, such as amantadine and interferon, are good examples of universal inhibitors for preventing and controlling viral infections. Therefore, scientists should give priority to the design, screening, and development of pan-coronavirus inhibitors, which are easier to realize and bring benefits to people faster at the early stage of infection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Z. and L.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L. and S.C.; writing—review and revision, H.O. and L.R.; supervision, L.R.; and funding acquisition, L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant No. 31772747], the Jilin Province Science and Technology Development Projects [Grant No. 20200402043NC]. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chen, S.; Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; Ouyang, H.; Ren, L. Viruses from poultry and livestock pose continuous threats to human beings. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2022344118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C.E.; Yount, B.L.; Graham, R.L.; Leist, S.R.; Hou, Y.J.; Dinnon, K.H., 3rd; Sims, A.C.; Swanstrom, J.; Gully, K.; Scobey, T.D.; et al. Swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus replication in primary human cells reveals potential susceptibility to infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 26915–26925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, G.; Wang, Y.; Ren, W.; Zhao, X.; Ji, F.; Zhu, Y.; Feng, F.; Gong, M.; Ju, X.; et al. Functional and genetic analysis of viral receptor ACE2 orthologs reveals a broad potential host range of SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2025373118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koff, W.C.; Berkley, S.F. A universal coronavirus vaccine. Science 2021, 371, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Shi, Z.L. SARS-CoV-2 spillover events. Science 2021, 371, 120–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giurgea, L.T.; Han, A.; Memoli, M.J. Universal coronavirus vaccines: The time to start is now. NPJ Vaccines 2020, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Beltran, W.F.; Lam, E.C.; St Denis, K.; Nitido, A.D.; Garcia, Z.H.; Hauser, B.M.; Feldman, J.; Pavlovic, M.N.; Gregory, D.J.; Poznansky, M.C.; et al. Multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants escape neutralization by vaccine-induced humoral immunity. Cell 2021, 184, 2372–2383.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, F.; Archer, B.; Laurenson-Schafer, H.; Jinnai, Y.; Konings, F.; Batra, N.; Pavlin, B.; Vandemaele, K.; Van Kerkhove, M.D.; Jombart, T.; et al. Increased transmissibility and global spread of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern as at June 2021. Euro Surveill 2021, 26, 2100509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCallum, M.; Bassi, J.; De Marco, A.; Chen, A.; Walls, A.C.; Di Iulio, J.; Tortorici, M.A.; Navarro, M.J.; Silacci-Fregni, C.; Saliba, C.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 immune evasion by the B.1.427/B.1.429 variant of concern. Science 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, T.; Lavine, C.L.; Rawson, S.; Peng, H.; Zhu, H.; Anand, K.; Tong, P.; Gautam, A.; et al. Structural basis for enhanced infectivity and immune evasion of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Science 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarevic, I.; Pravica, V.; Miljanovic, D.; Cupic, M. Immune Evasion of SARS-CoV-2 Emerging Variants: What Have We Learnt So Far? Viruses 2021, 13, 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, J.T.; Cheng, T.R.; Juang, Y.P.; Ma, H.H.; Wu, Y.T.; Yang, W.B.; Cheng, C.W.; Chen, X.; Chou, T.H.; Shie, J.J.; et al. Identification of existing pharmaceuticals and herbal medicines as inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2021579118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.W. Current and Future Direct-Acting Antivirals Against COVID-19. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 587944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliamonte, M.S.; Abid, N.; Borocci, S.; Sangiovanni, E.; Ostrov, D.A.; Kosakovsky Pond, S.L.; Salemi, M.; Chillemi, G.; Mavian, C. Multiple Recombination Events and Strong Purifying Selection at the Origin of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein Increased Correlated Dynamic Movements. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, S.; Liu, M.; Wang, C.; Xu, W.; Lan, Q.; Feng, S.; Qi, F.; Bao, L.; Du, L.; Liu, S.; et al. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 (previously 2019-nCoV) infection by a highly potent pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor targeting its spike protein that harbors a high capacity to mediate membrane fusion. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yuan, S.; Yin, X.; Meng, X.; Chan, J.F.; Ye, Z.W.; Riva, L.; Pache, L.; Chan, C.C.; Lai, P.M.; Chan, C.C.; et al. Clofazimine broadly inhibits coronaviruses including SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2021, 593, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Xia, S.; Zhu, Y.; Lu, L.; Jiang, S. Pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitors as the hope for today and tomorrow. Protein Cell 2021, 12, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartenian, E.; Nandakumar, D.; Lari, A.; Ly, M.; Tucker, J.M.; Glaunsinger, B.A. The molecular virology of coronaviruses. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 12910–12934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V’Kovski, P.; Kratzel, A.; Steiner, S.; Stalder, H.; Thiel, V. Coronavirus biology and replication: Implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, S.; Yan, L.; Xu, W.; Agrawal, A.S.; Algaissi, A.; Tseng, C.K.; Wang, Q.; Du, L.; Tan, W.; Wilson, I.A.; et al. A pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor targeting the HR1 domain of human coronavirus spike. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav4580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yang, C.; Pan, X.; Huang, Y.; Cheng, C.; Xu, X.; Wu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Shang, W.; Niu, X.; Wan, Y.; et al. Drug Repurposing of Itraconazole and Estradiol Benzoate against COVID-19 by Blocking SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein-Mediated Membrane Fusion. Adv. Ther. 2021, 4, 2000224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, T.; Bidon, M.; Jaimes, J.A.; Whittaker, G.R.; Daniel, S. Coronavirus membrane fusion mechanism offers a potential target for antiviral development. Antivir. Res. 2020, 178, 104792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, A.L.; Millet, J.K.; Daniel, S.; Freed, J.H.; Whittaker, G.R. The SARS-CoV Fusion Peptide Forms an Extended Bipartite Fusion Platform that Perturbs Membrane Order in a Calcium-Dependent Manner. J. Mol. Biol. 2017, 429, 3875–3892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, P.; Huang, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, S. Inhibitory effect on SARS-CoV-2 infection of neferine by blocking Ca(2+) -dependent membrane fusion. J. Med. Virol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.L.; Huang, L.Y.; Wang, K.; Gu, C.J.; Hu, J.; Zhang, G.J.; Xu, W.; Xie, Y.H.; Tang, N.; Huang, A.L. Identification of bis-benzylisoquinoline alkaloids as SARS-CoV-2 entry inhibitors from a library of natural products. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Kusov, Y.; Hilgenfeld, R. Nsp3 of coronaviruses: Structures and functions of a large multi-domain protein. Antivir. Res. 2018, 149, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Wang, D.; Zhou, J.; Pan, T.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Lv, M.; Ye, X.; Peng, G.; Fang, L.; et al. Porcine Deltacoronavirus nsp5 Antagonizes Type I Interferon Signaling by Cleaving STAT2. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e00003-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stobart, C.C.; Sexton, N.R.; Munjal, H.; Lu, X.; Molland, K.L.; Tomar, S.; Mesecar, A.D.; Denison, M.R. Chimeric exchange of coronavirus nsp5 proteases (3CLpro) identifies common and divergent regulatory determinants of protease activity. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 12611–12618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vatansever, E.C.; Yang, K.S.; Drelich, A.K.; Kratch, K.C.; Cho, C.C.; Kempaiah, K.R.; Hsu, J.C.; Mellott, D.M.; Xu, S.; Tseng, C.K.; et al. Bepridil is potent against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2012201118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Li, Y.S.; Zeng, R.; Liu, F.L.; Luo, R.H.; Huang, C.; Wang, Y.F.; Zhang, J.; Quan, B.; Shen, C.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 M(pro) inhibitors with antiviral activity in a transgenic mouse model. Science 2021, 371, 1374–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockbaum, G.J.; Reyes, A.C.; Lee, J.M.; Tilvawala, R.; Nalivaika, E.A.; Ali, A.; Kurt Yilmaz, N.; Thompson, P.R.; Schiffer, C.A. Crystal Structure of SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease in Complex with the Non-Covalent Inhibitor ML188. Viruses 2021, 13, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirzada, R.H.; Haseeb, M.; Batool, M.; Kim, M.; Choi, S. Remdesivir and Ledipasvir among the FDA-Approved Antiviral Drugs Have Potential to Inhibit SARS-CoV-2 Replication. Cells 2021, 10, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elghoneimy, L.K.; Ismail, M.I.; Boeckler, F.M.; Azzazy, H.M.E.; Ibrahim, T.M. Facilitating SARS CoV-2 RNA-Dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) drug discovery by the aid of HCV NS5B palm subdomain binders: In silico approaches and benchmarking. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 134, 104468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, C.J.; Tchesnokov, E.P.; Schinazi, R.F.; Gotte, M. Molnupiravir promotes SARS-CoV-2 mutagenesis via the RNA template. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 100770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, L.; Ren, L. Antiviral mechanisms of candidate chemical medicines and traditional Chinese medicines for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Virus Res. 2020, 286, 198073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picarazzi, F.; Vicenti, I.; Saladini, F.; Zazzi, M.; Mori, M. Targeting the RdRp of Emerging RNA Viruses: The Structure-Based Drug Design Challenge. Molecules 2020, 25, 5695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Li, P.; Ju, X.; Rao, J.; Huang, W.; Ren, L.; Zhang, S.; Xiong, T.; Xu, K.; Zhou, X.; et al. In vivo structural characterization of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome identifies host proteins vulnerable to repurposed drugs. Cell 2021, 184, 1865–1883.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.H.; Min, J.S.; Jeon, S.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Park, T.; Park, D.; Jang, M.S.; Park, C.M.; Song, J.H.; et al. Lycorine, a non-nucleoside RNA dependent RNA polymerase inhibitor, as potential treatment for emerging coronavirus infections. Phytomedicine 2021, 86, 153440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, A.; Selisko, B.; Le, N.T.; Huchting, J.; Touret, F.; Piorkowski, G.; Fattorini, V.; Ferron, F.; Decroly, E.; Meier, C.; et al. Rapid incorporation of Favipiravir by the fast and permissive viral RNA polymerase complex results in SARS-CoV-2 lethal mutagenesis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.; Li, X.; Kumar, S.; Jockusch, S.; Chien, M.; Tao, C.; Morozova, I.; Kalachikov, S.; Kirchdoerfer, R.N.; Russo, J.J. Nucleotide analogues as inhibitors of SARS-CoV Polymerase. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2020, 8, e00674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Yin, W.; Xu, H.E. RNA-dependent RNA polymerase: Structure, mechanism, and drug discovery for COVID-19. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 538, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirchdoerfer, R.N.; Ward, A.B. Structure of the SARS-CoV nsp12 polymerase bound to nsp7 and nsp8 co-factors. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maio, N.; Lafont, B.A.P.; Sil, D.; Li, Y.; Bollinger, J.M., Jr.; Krebs, C.; Pierson, T.C.; Linehan, W.M.; Rouault, T.A. Fe-S cofactors in the SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase are potential antiviral targets. Science 2021, eabi5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, P.R.; Scaiola, A.; Loughran, G.; Leibundgut, M.; Kratzel, A.; Meurs, R.; Dreos, R.; O’Connor, K.M.; McMillan, A.; Bode, J.W.; et al. Structural basis of ribosomal frameshifting during translation of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA genome. Science 2021, 372, 1306–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Abriola, L.; Niederer, R.O.; Pedersen, S.F.; Alfajaro, M.M.; Silva Monteiro, V.; Wilen, C.B.; Ho, Y.C.; Gilbert, W.V.; Surovtseva, Y.V.; et al. Restriction of SARS-CoV-2 replication by targeting programmed -1 ribosomal frameshifting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2023051118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plant, E.P.; Dinman, J.D. The role of programmed-1 ribosomal frameshifting in coronavirus propagation. Front. Biosci. 2008, 13, 4873–4881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kelly, J.A.; Olson, A.N.; Neupane, K.; Munshi, S.; San Emeterio, J.; Pollack, L.; Woodside, M.T.; Dinman, J.D. Structural and functional conservation of the programmed -1 ribosomal frameshift signal of SARS coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 10741–10748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neupane, K.; Munshi, S.; Zhao, M.; Ritchie, D.B.; Ileperuma, S.M.; Woodside, M.T. Anti-Frameshifting Ligand Active against SARS Coronavirus-2 Is Resistant to Natural Mutations of the Frameshift-Stimulatory Pseudoknot. J. Mol. Biol. 2020, 432, 5843–5847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cai, H.; Pan, J.; Xiang, N.; Tien, P.; Ahola, T.; Guo, D. Functional screen reveals SARS coronavirus nonstructural protein nsp14 as a novel cap N7 methyltransferase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 3484–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vithani, N.; Ward, M.D.; Zimmerman, M.I.; Novak, B.; Borowsky, J.H.; Singh, S.; Bowman, G.R. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp16 activation mechanism and a cryptic pocket with pan-coronavirus antiviral potential. Biophys. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, K.; Ramirez, S.I.; Lokugamage, K.G.; Makino, S. Coronavirus nonstructural protein 1: Common and distinct functions in the regulation of host and viral gene expression. Virus Res. 2015, 202, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simeoni, M.; Cavinato, T.; Rodriguez, D.; Gatfield, D. I(nsp1)ecting SARS-CoV-2-ribosome interactions. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schubert, K.; Karousis, E.D.; Jomaa, A.; Scaiola, A.; Echeverria, B.; Gurzeler, L.A.; Leibundgut, M.; Thiel, V.; Muhlemann, O.; Ban, N. SARS-CoV-2 Nsp1 binds the ribosomal mRNA channel to inhibit translation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020, 27, 959–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tidu, A.; Janvier, A.; Schaeffer, L.; Sosnowski, P.; Kuhn, L.; Hammann, P.; Westhof, E.; Eriani, G.; Martin, F. The viral protein NSP1 acts as a ribosome gatekeeper for shutting down host translation and fostering SARS-CoV-2 translation. Rna 2020, 27, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, W.M.; Luna, J.M.; Hoffmann, H.H.; Sanchez-Rivera, F.J.; Leal, A.A.; Ashbrook, A.W.; Le Pen, J.; Ricardo-Lax, I.; Michailidis, E.; Peace, A.; et al. Genome-Scale Identification of SARS-CoV-2 and Pan-coronavirus Host Factor Networks. Cell 2021, 184, 120–132.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, H.H.; Sanchez-Rivera, F.J.; Schneider, W.M.; Luna, J.M.; Soto-Feliciano, Y.M.; Ashbrook, A.W.; Le Pen, J.; Leal, A.A.; Ricardo-Lax, I.; Michailidis, E.; et al. Functional interrogation of a SARS-CoV-2 host protein interactome identifies unique and shared coronavirus host factors. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 267–280.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Alfajaro, M.M.; DeWeirdt, P.C.; Hanna, R.E.; Lu-Culligan, W.J.; Cai, W.L.; Strine, M.S.; Zhang, S.M.; Graziano, V.R.; Schmitz, C.O.; et al. Genome-wide CRISPR Screens Reveal Host Factors Critical for SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Cell 2021, 184, 76–91.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, D.W.; Jumper, C.C.; Ackerman, P.J.; Bracha, D.; Donlic, A.; Kim, H.; Kenney, D.; Castello-Serrano, I.; Suzuki, S.; Tamura, T.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 requires cholesterol for viral entry and pathological syncytia formation. Elife 2021, 10, e65962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardacci, R.; Colavita, F.; Castilletti, C.; Lapa, D.; Matusali, G.; Meschi, S.; Del Nonno, F.; Colombo, D.; Capobianchi, M.R.; Zumla, A.; et al. Evidences for lipid involvement in SARS-CoV-2 cytopathogenesis. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proto, M.C.; Fiore, D.; Piscopo, C.; Pagano, C.; Galgani, M.; Bruzzaniti, S.; Laezza, C.; Gazzerro, P.; Bifulco, M. Lipid homeostasis and mevalonate pathway in COVID-19: Basic concepts and potential therapeutic targets. Prog. Lipid Res. 2021, 82, 101099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Li, W.; Hui, H.; Tiwari, S.K.; Zhang, Q.; Croker, B.A.; Rawlings, S.; Smith, D.; Carlin, A.F.; Rana, T.M. Cholesterol 25-Hydroxylase inhibits SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses by depleting membrane cholesterol. EMBO J. 2020, 39, e106057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingues, M.M.; Gomes, B.; Hollmann, A.; Santos, N.C. 25-Hydroxycholesterol Effect on Membrane Structure and Mechanical Properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaender, S.; Mar, K.B.; Michailidis, E.; Kratzel, A.; Boys, I.N.; V’Kovski, P.; Fan, W.; Kelly, J.N.; Hirt, D.; Ebert, N.; et al. LY6E impairs coronavirus fusion and confers immune control of viral disease. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 1330–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferle, S.; Schopf, J.; Kogl, M.; Friedel, C.C.; Muller, M.A.; Carbajo-Lozoya, J.; Stellberger, T.; von Dall’Armi, E.; Herzog, P.; Kallies, S.; et al. The SARS-coronavirus-host interactome: Identification of cyclophilins as target for pan-coronavirus inhibitors. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carbajo-Lozoya, J.; Ma-Lauer, Y.; Malesevic, M.; Theuerkorn, M.; Kahlert, V.; Prell, E.; von Brunn, B.; Muth, D.; Baumert, T.F.; Drosten, C.; et al. Human coronavirus NL63 replication is cyclophilin A-dependent and inhibited by non-immunosuppressive cyclosporine A-derivatives including Alisporivir. Virus Res. 2014, 184, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satarker, S.; Nampoothiri, M. Structural Proteins in Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2. Arch. Med. Res. 2020, 51, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Meng, B.; Xiang, J.; Wilson, I.A.; Yang, B. Crystal structure of the post-fusion core of the Human coronavirus 229E spike protein at 1.86 A resolution. Acta Crystallogr. D Struct. Biol. 2018, 74, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Artese, A.; Svicher, V.; Costa, G.; Salpini, R.; Di Maio, V.C.; Alkhatib, M.; Ambrosio, F.A.; Santoro, M.M.; Assaraf, Y.G.; Alcaro, S.; et al. Current status of antivirals and druggable targets of SARS CoV-2 and other human pathogenic coronaviruses. Drug Resist. Updates 2020, 53, 100721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, R.D.; Schmitz, K.S.; Bovier, F.T.; Predella, C.; Khao, J.; Noack, D.; Haagmans, B.L.; Herfst, S.; Stearns, K.N.; Drew-Bear, J.; et al. Intranasal fusion inhibitory lipopeptide prevents direct-contact SARS-CoV-2 transmission in ferrets. Science 2021, 371, 1379–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Zhu, Y.; Yan, H.; Wu, T.; Chong, H.; He, Y. Pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitors possess potent inhibitory activity against HIV-1, HIV-2, and simian immunodeficiency virus. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2021, 10, 810–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Xu, W.; Gu, C.; Cai, X.; Qu, D.; Lu, L.; Xie, Y.; Jiang, S. Griffithsin with A Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Activity by Binding Glycans in Viral Glycoprotein Exhibits Strong Synergistic Effect in Combination with A Pan-Coronavirus Fusion Inhibitor Targeting SARS-CoV-2 Spike S2 Subunit. Virol. Sin. 2020, 35, 857–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Yang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Ge, J.; Huang, Y.C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, T.; Gao, S.; et al. Coupling of N7-methyltransferase and 3′-5′ exoribonuclease with SARS-CoV-2 polymerase reveals mechanisms for capping and proofreading. Cell 2021, 184, 3474–3485.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.E.; Wang, Y.; Du, X.; Zhang, T.; Mak, H.Y.; Hancock, S.E.; McEwen, H.; Pandzic, E.; Whan, R.M.; Aw, Y.C.; et al. TMEM41B and VMP1 are scramblases and regulate the distribution of cholesterol and phosphatidylserine. J. Cell Biol. 2021, 220, e202103105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schloer, S.; Brunotte, L.; Goretzko, J.; Mecate-Zambrano, A.; Korthals, N.; Gerke, V.; Ludwig, S.; Rescher, U. Targeting the endolysosomal host-SARS-CoV-2 interface by clinically licensed functional inhibitors of acid sphingomyelinase (FIASMA) including the antidepressant fluoxetine. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 2245–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tummino, T.A.; Rezelj, V.V.; Fischer, B.; Fischer, A.; O’Meara, M.J.; Monel, B.; Vallet, T.; White, K.M.; Zhang, Z.; Alon, A.; et al. Drug-induced phospholipidosis confounds drug repurposing for SARS-CoV-2. Science 2021, eabi4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Hozumi, Y.; Zheng, Y.H.; Yin, C.; Wei, G.W. Host Immune Response Driving SARS-CoV-2 Evolution. Viruses 2020, 12, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Starr, T.N.; Greaney, A.J.; Addetia, A.; Hannon, W.W.; Choudhary, M.C.; Dingens, A.S.; Li, J.Z.; Bloom, J.D. Prospective mapping of viral mutations that escape antibodies used to treat COVID-19. Science 2021, 371, 850–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreano, E.; Piccini, G.; Licastro, D.; Casalino, L.; Johnson, N.V.; Paciello, I.; Monego, S.D.; Pantano, E.; Manganaro, N.; Manenti, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 escape in vitro from a highly neutralizing COVID-19 convalescent plasma. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, S.; Srivastava, R.; Coulon, P.G.; Dhanushkodi, N.R.; Chentoufi, A.A.; Tifrea, D.F.; Edwards, R.A.; Figueroa, C.J.; Schubl, S.D.; Hsieh, L.; et al. Genome-Wide B Cell, CD4(+), and CD8(+) T Cell Epitopes That Are Highly Conserved between Human and Animal Coronaviruses, Identified from SARS-CoV-2 as Targets for Preemptive Pan-Coronavirus Vaccines. J. Immunol. 2021, 206, 2566–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.; Choudhary, M.C.; Regan, J.; Sparks, J.A.; Padera, R.F.; Qiu, X.; Solomon, I.H.; Kuo, H.H.; Boucau, J.; Bowman, K.; et al. Persistence and Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in an Immunocompromised Host. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2291–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Kaabi, N.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, S.; Yang, Y.; Al Qahtani, M.M.; Abdulrazzaq, N.; Al Nusair, M.; Hassany, M.; Jawad, J.S.; Abdalla, J.; et al. Effect of 2 Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines on Symptomatic COVID-19 Infection in Adults: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Zou, J.; Fontes-Garfias, C.R.; Xia, H.; Swanson, K.A.; Cutler, M.; Cooper, D.; et al. Neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 spike 69/70 deletion, E484K and N501Y variants by BNT162b2 vaccine-elicited sera. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 620–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Yisimayi, A.; Bai, Y.; Huang, W.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yuan, T.; An, R.; Wang, J.; Xiao, T.; et al. Humoral immune response to circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants elicited by inactivated and RBD-subunit vaccines. Cell Res. 2021, 31, 732–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, E.M.; Yang, X.; Blackman, C.; Feifer, R.A.; Gravenstein, S.; Mor, V. Incident SARS-CoV-2 Infection among mRNA-Vaccinated and Unvaccinated Nursing Home Residents. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Raddad, L.J.; Chemaitelly, H.; Butt, A.A.; National Study Group for COVID-19 Vaccination. Effectiveness of the BNT162b2 Covid-19 Vaccine against the B.1.1.7 and B.1.351 Variants. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buss, L.F.; Prete, C.A., Jr.; Abrahim, C.M.M.; Mendrone, A., Jr.; Salomon, T.; de Almeida-Neto, C.; Franca, R.F.O.; Belotti, M.C.; Carvalho, M.; Costa, A.G.; et al. Three-quarters attack rate of SARS-CoV-2 in the Brazilian Amazon during a largely unmitigated epidemic. Science 2021, 371, 288–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Soh, W.T.; Kishikawa, J.I.; Hirose, M.; Nakayama, E.E.; Li, S.; Sasai, M.; Suzuki, T.; Tada, A.; Arakawa, A.; et al. An infectivity-enhancing site on the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein targeted by antibodies. Cell 2021, 184, 3452–3466.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavine, J.S.; Bjornstad, O.N.; Antia, R. Immunological characteristics govern the transition of COVID-19 to endemicity. Science 2021, 371, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldman, J.; Bals, J.; Denis, K.S.; Lam, E.C.; Hauser, B.M.; Ronsard, L.; Sangesland, M.; Moreno, T.B.; Okonkwo, V.; Hartojo, N.; et al. Naive human B cells can neutralize SARS-CoV-2 through recognition of its receptor binding domain. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoddard, C.I.; Galloway, J.; Chu, H.Y.; Shipley, M.M.; Sung, K.; Itell, H.L.; Wolf, C.R.; Logue, J.K.; Magedson, A.; Garrett, M.E.; et al. Epitope profiling reveals binding signatures of SARS-CoV-2 immune response in natural infection and cross-reactivity with endemic human CoVs. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiakolas, A.R.; Kramer, K.J.; Wrapp, D.; Richardson, S.I.; Schafer, A.; Wall, S.; Wang, N.; Janowska, K.; Pilewski, K.A.; Venkat, R.; et al. Cross-reactive coronavirus antibodies with diverse epitope specificities and Fc effector functions. Cell Rep. Med. 2021, 2, 100313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedry, J.; Hurdiss, D.L.; Wang, C.; Li, W.; Obal, G.; Drulyte, I.; Du, W.; Howes, S.C.; van Kuppeveld, F.J.M.; Forster, F.; et al. Structural insights into the cross-neutralization of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 by the human monoclonal antibody 47D11. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabf5632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routhu, N.K.; Cheedarla, N.; Bollimpelli, V.S.; Gangadhara, S.; Edara, V.V.; Lai, L.; Sahoo, A.; Shiferaw, A.; Styles, T.M.; Floyd, K.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 RBD trimer protein adjuvanted with Alum-3M-052 protects from SARS-CoV-2 infection and immune pathology in the lung. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, B.M.; Sangesland, M.; Lam, E.C.; Feldman, J.; Yousif, A.S.; Caradonna, T.M.; Balazs, A.B.; Lingwood, D.; Schmidt, A.G. Engineered receptor binding domain immunogens elicit pan-coronavirus neutralizing antibodies. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, D.R.; Schafer, A.; Leist, S.R.; De la Cruz, G.; West, A.; Atochina-Vasserman, E.N.; Lindesmith, L.C.; Pardi, N.; Parks, R.; Barr, M.; et al. Chimeric spike mRNA vaccines protect against Sarbecovirus challenge in mice. Science 2021, eabi4506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, A.A.; Gnanapragasam, P.N.P.; Lee, Y.E.; Hoffman, P.R.; Ou, S.; Kakutani, L.M.; Keeffe, J.R.; Wu, H.J.; Howarth, M.; West, A.P.; et al. Mosaic nanoparticles elicit cross-reactive immune responses to zoonotic coronaviruses in mice. Science 2021, 371, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, P.A.; Das, H.; Liu, H.; Kummerer, B.M.; Gohr, F.N.; Jenster, L.M.; Schiffelers, L.D.J.; Tesfamariam, Y.M.; Uchima, M.; Wuerth, J.D.; et al. Structure-guided multivalent nanobodies block SARS-CoV-2 infection and suppress mutational escape. Science 2021, 371, eabe6230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, M.G.; Chen, W.H.; Sankhala, R.S.; Hajduczki, A.; Thomas, P.V.; Choe, M.; Chang, W.; Peterson, C.E.; Martinez, E.; Morrison, E.B.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 ferritin nanoparticle vaccines elicit broad SARS coronavirus immunogenicity. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, E.S.; Schramm, C.A.; Shi, W.; Pegu, A.; Oloniniyi, O.K.; Henry, A.R.; Darko, S.; et al. Ultrapotent antibodies against diverse and highly transmissible SARS-CoV-2 variants. Science 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Sang, Z.; Kim, Y.J.; Xiang, Y.; Cohen, T.; Belford, A.K.; Huet, A.; Conway, J.F.; Sun, J.; Taylor, D.J.; et al. Potent neutralizing nanobodies resist convergent circulating variants of SARS-CoV-2 by targeting novel and conserved epitopes. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhao, J.; Mangalam, A.K.; Channappanavar, R.; Fett, C.; Meyerholz, D.K.; Agnihothram, S.; Baric, R.S.; David, C.S.; Perlman, S. Airway Memory CD4(+) T Cells Mediate Protective Immunity against Emerging Respiratory Coronaviruses. Immunity 2016, 44, 1379–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, M.; Zeng, J.; Li, R.; Wen, Z.; Cai, Y.; Wallin, J.; Shu, Y.; Du, X.; Sun, C. Rational Design of a Pan-Coronavirus Vaccine Based on Conserved CTL Epitopes. Viruses 2021, 13, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, T.R.; Dhamdhere, G.; Liu, Y.; Lin, X.; Goudy, L.; Zeng, L.; Chemparathy, A.; Chmura, S.; Heaton, N.S.; Debs, R.; et al. Development of CRISPR as an Antiviral Strategy to Combat SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza. Cell 2020, 181, 865–876.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhury, S.; Hutter, J.; Bolton, J.S.; Hakre, S.; Mose, E.; Wooten, A.; O’Connell, W.; Hudak, J.; Krebs, S.J.; Darden, J.M.; et al. Serological profiles of pan-coronavirus-specific responses in COVID-19 patients using a multiplexed electro-chemiluminescence-based testing platform. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0252628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).