Advances in Entomopathogen Isolation: A Case of Bacteria and Fungi

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Isolation of Entomopathogenic Bacteria

2.1. Milky Disease-Causing Paenibacillus spp.

- (a)

- Disinfect the surface of the larvae of grubs (Coleoptera) with 0.5% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl).

- (b)

- Pinch the cadaver using a sterilized needle and collect the emerging drops in sterilized water.

- (c)

- Culture the dilutions of the drops on St. Julian medium (J-Medium) (Appendix A, Medium 1) [26], or Mueller-Hinton broth, yeast extract, potassium phosphate, glucose, and pyruvate (MYPGP) (Appendix A, Medium 2) agar [27].

- (a)

- Make soil suspensions by adding 2 g soil to 20 mL sterilized water.

- (b)

- Make a germinating medium, i.e., 0.5% yeast extract and 0.1% glucose.

- (c)

- Adjust the pH to 6.5.

- (d)

- Add germinating medium into the soil suspension at 1:50 ratio.

- (e)

- Apply series of heat shocks at 70 °C for 20 min after every hour, 7 times.

- (f)

- Spread the aliquot on J-Medium and incubate for 7 h at 28 °C, anaerobically.

2.2. Amber Disease-Causing Serratia spp.

- (a)

- Soil inoculums or hemolymph of the diseased larvae can be isolated on Caprylate-thallous agar (CTA) (Appendix A, Medium 3) [31].

- (b)

- Culturing is done by pulling and separating the anterior end of the cadavers. The gut contents are then cultured on CTA plates.

- (c)

- Serratia marcescens produces colonies which are red in color. Cream-colured bacterial colonies formed on CTA can then be transferred into different selective media for the identification of Serratia spp. [30].

- (d)

- The production of a halo on a Deoxyribonuclease (DNase)-Toluidine Blue agar (Appendix A, Medium 4) when incubated at 30 °C for 24 h, indicates the presence of Serratia spp. [32]. Thereafter, the production of blue or green colonies on adonitol agar (Appendix A, Medium 5) confirms S. proteamaculans. The formation of yellow colonies on adonitol agar hints the presence of S. entomophila, which can be confirmed by the growth on itaconate agar (Appendix A, Medium 6) at 30 °C after 96 h [25]. Further molecular approaches targeting specific DNA regions can distinguish pathogenic strains from the non-pathogenic ones.

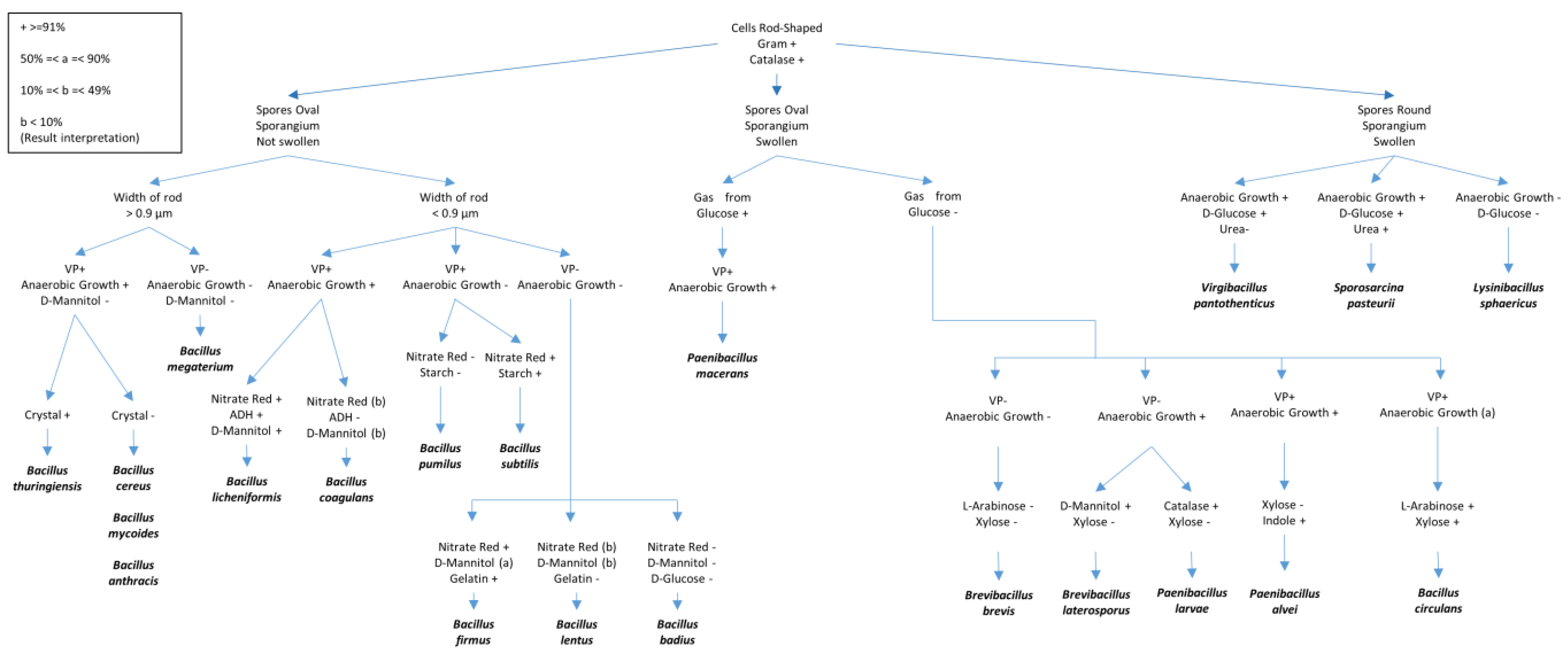

2.3. Other Bacteria from the Class Bacilli

- (a)

- Isolation can be done from soils (2–4 g in 10 mL sterilized water), insects (0.2–0.4 g/mL sterilized water), or water samples (after concentrating using 0.22 µm filter).

- (b)

- Heat the samples in a water bath at 80 °C for 10 min to kill the vegetative cells.

- (c)

- Perform serial dilutions, generally at 10−2 and 10−3, and culture the inoculums on Minimal Basal Salt (MBS) medium (Appendix A, Medium 7), as suggested by Kalfon et al. [33]. Continue subculturing until pure cultures are obtained.

- (d)

3. Isolation of Entomopathogenic Fungi

3.1. Isolations from Naturally Mycosed Insect Cadavers

- (a)

- Insect cadavers are brought to the laboratory as separate entities in sterile tubes.

- (b)

- Insects are observed under a stereomicroscope (40×) for probable mycosis.

- (c)

- In case of a visible mycosis, the insects are surface sterilized using 70% ethanol or 1% NaOCl, for 3 min, followed by 3 distinct washes with 100 mL of sterilized water. Then, the sporulating EPF from the insect cadaver is plated directly.

- (d)

- Cadavers are then cultured on a selective medium at 22 °C for up to 3 weeks, depending on the time taken by the fungi for germination and proliferation. In case of no germination, the cadavers can be homogenized and plated on the selective medium. Details of the different selective medium are provided later in the text.

- (e)

- Obtained fungi are subcultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA) (Appendix A, Medium 8) or Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) (Appendix A, Medium 9) until pure culture is obtained.

- (f)

- (g)

- Molecular identifications can be done by extracting the DNA and performing PCR for the amplification and subsequent sequencing of the nuclear internal transcribed spacer (nrITS) region of the fungal nuclear ribosomal DNA, as described in Yurkov et al. [40].

3.2. Isolations from Soils

3.2.1. Soil Suspension Culture

Metarhizium spp.

Beauveria spp.

Purpureocillium spp.

Lecanicillium spp.

Clonostachys spp.

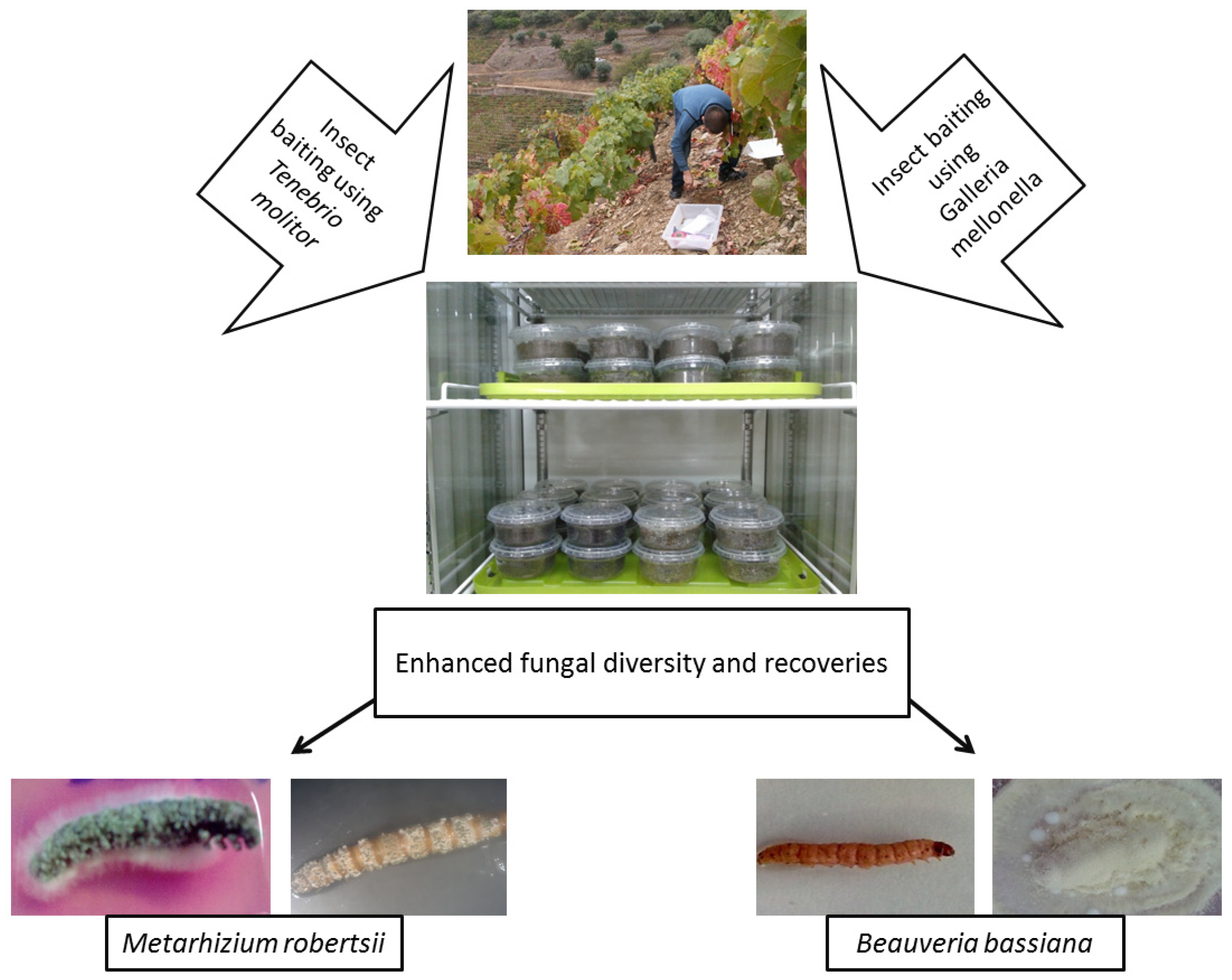

3.2.2. Insect Baiting

Galleria-Bait Method or Tenebrio-Bait Method

Galleria-Tenebrio-Bait Method

Other Bait Insects

3.3. Isolation from Phyllosphere

3.4. Molecular Identifications of the Isolated Entomopathogenic Fungi

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- (1)

- Caprylate-thallous agar (CTA).

- (1a)

- Solution A

| Reagents and Chemicals | Chemical Formula (If Applicable) | Quantity |

| Monopotassium phosphate | KH2PO4 | 0.68 g |

| Magnesium sulfate heptahydrate | MgSO4.7H2O | 0.3 g |

| Dipotassium phosphate | K2HPO4 | 0.15 g |

| Thallium(I) sulphate | Tl2SO4 | 0.25 g |

| Yeast Extract | 1 g | |

| Calcium chloride | CaCl2 | 0.1 g |

| Caprylic (n-octanoic) acid | CH3(CH2)6.COOH | 1.1 mL |

| Trace element solution | 10 mL | |

| Distilled water | H2O | 1 L |

| Reagents and Chemicals | Chemical Formula (If Applicable) | Quantity |

| Ferrous sulphate heptahydrate | FeSO4.7H2O | 0.055 g |

| Trihydrogen phosphate | H3PO4 | 1.96 g |

| Zinc sulphate heptahydrate | ZnSO4.7H2O | 0.0287 g |

| Manganese(II) sulphate monohydrate | MnSO4.H2O | 0.0223 g |

| Copper(II) sulphate pentahydrate | CuSO4.5H2O | 0.0025 g |

| Cobalt(II) nitrate hexahydrate | Co(NO3)2.6H2O | 0.003 g |

| Boric acid | H3BO3 | 0.0062 g |

| Distilled water | H2O | 1 L |

- (1b)

- Solution B

| Reagents and Chemicals | Chemical Formula (If Applicable) | Quantity |

| Ammonium sulphate | (NH4)2SO4 | 1.0 g |

| Sodium chloride | NaCl | 7.0 g |

| Agar | 15 g | |

| Distilled water | H2O | 1 L |

- (2)

- Deoxyribonuclease (DNase)-Toluidine Blue agar.

| Reagents and Chemicals | Chemical Formula (If Applicable) | Quantity |

| Deoxyribonuclease test agar | 37.8 g | |

| Toluidine blue 0.1% w/v solution | NaCl | 90.0 ml |

| L-arabinose | C5H10O5 | 10.0 g |

| Distilled water | H2O | 900 mL |

- (3)

- St. Julian medium (J-medium).

| Reagents and Chemicals | Chemical Formula (If Applicable) | Quantity |

| Yeast extract | 15 g | |

| Tryptone | 5 g | |

| Dipotassium phosphate | K2HPO4 | 3 g |

| Glucose (sterilized by filtration) | C6H12O6 | 2.0 g |

| Distilled water | H2O | 1 L |

- (4)

- Mueller-Hinton broth, yeast extract, potassium phosphate, glucose and pyruvate (MYPGP) medium.

| Reagents and Chemicals | Chemical Formula (If Applicable) | Quantity |

| Dipotassium phosphate | K2HPO4 | 3.0 g |

| Sodium pyruvate | C3H3O3Na | 1.0 g |

| Mueller-Hinton broth | 10.0 g | |

| Glucose (sterilized by filtration) | C6H12O6 | 2.0 g |

| Yeast Extract | 10.0 g | |

| Distilled water | 1 L |

- (5)

- Adonitol agar.

| Reagents and Chemicals | Chemical Formula (If Applicable) | Quantity |

| Sodium chloride | NaCl | 4.17 g |

| Adonitol | C5H12O5 | 5.0 g |

| Peptone | 8.33 g | |

| Bacto agar | 12.5 g | |

| Bromothymol blue solution | C27H28Br2O5S | 10 mL |

| Distilled water | H2O | 990 mL |

| Reagents and Chemicals | Chemical Formula (If Applicable) | Quantity |

| Bromothymol blue | C27H28Br2O5S | 0.2 g |

| Sodium hydroxide (0.1M) | NaOH | 5 mL |

| Distilled water | H2O | 900 mL |

- (6)

- Itaconate agar.

| Reagents and Chemicals | Chemical Formula (If Applicable) | Quantity |

| Monopotassium phosphate | KH2PO4 | 3.0 g |

| Disodium phosphate | Na2HPO4 | 6.0 g |

| Sodium chloride | NaCl | 0.5 g |

| Ammonium chloride | NH4Cl | 1.0 g |

| Calcium chloride solution (sterilised) (0.01M) | CaCl2 | 10.0 mL |

| Magnesium sulfate heptahydrate (sterilised) (1M) | MgSO4.7H2O | 1.0 mL |

| Itaconic acid solution (filter sterilised) (20%) | C5H6O4 | 10 mL |

| Distilled water | H2O | 1 L |

- (7)

- Minimal Basal Salt (MBS) medium.

| Reagents and Chemicals | Chemical Formula (If Applicable) | Quantity |

| Monopotassium phosphate | KH2PO4 | 6.8 g |

| Magnesium sulfate heptahydrate | MgSO4.7H2O | 0.3 g |

| Manganese monohydrate sulphate | MnSO4.1H2O | 0.02 g |

| Ferric sulfate | Fe2(SO4)3 | 0.02 g |

| Zinc sulfate heptahydrate | ZnSO4.7H2O | 0.02 g |

| Calcium chloride | CaCl2 | 0.2 g |

| Tryptone | 10 g | |

| Yeast Extract | 2 g |

- (8)

- Potato Dextrose agar (PDA)

| Reagents and Chemicals | Chemical formula (If Applicable) | Quantity |

| Potato dextrose agar | 39.0 g | |

| Distilled water | H2O | 1 L |

- (9)

- Sabouraud Dextrose agar (SDA)

| Reagents and Chemicals | Chemical Formula (if Applicable) | Quantity |

| Sabouraud dextrose agar | 65.0 g | |

| Distilled water | H2O | 1 L |

- (10)

- Oatmeal Cetyl Trimethyl Ammonium Bromide (OM-CTAB) agar.

| Reagents and Chemicals | Chemical Formula (If Applicable) | Quantity |

| Oatmeal (cooked in distilled water) | 20.0 g | |

| Cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) | C19H42BrN | 0.6 g |

| Chloramphenicol | C11H12Cl2N2O5 | 0.5 g |

| Agar | 20 g | |

| Distilled water | H2O | To make upto 1L |

- (11)

- Dichloran Rose-Bengal Chloramphenicol agar (DRBCA).

| Reagents and Chemicals | Chemical Formula (If Applicable) | Quantity |

| Dichloran Rose-Bengal Chloramphenicol agar | 32.0 g | |

| Distilled water | H2O | 1 L |

- (12)

- Metarhizium Medium

| Reagents and Chemicals | Chemical Formula (If Applicable) | Quantity |

| Glucose | C6H12O6 | 10.0 g |

| Peptone | 10.0 g | |

| Oxgall | 15.0 g | |

| Agar | 35.0 g | |

| Dodine (N-dodecylguanidine monoacetate) | C15H33N3O2 | 10 mg |

| Cycloheximide | C15H23NO4 | 250 mg |

| Chloramphenicol | C11H12Cl2N2O5 | 500 mg |

| Distilled water | H2O | 1 L |

- (13)

- Chloramphenicol Thiabendazole Cycloheximide (CTC) medium.

| Reagents and Chemicals | Chemical Formula (If Applicable) | Quantity |

| Potato dextrose agar | 39.0 g | |

| Yeast extract | 0.5 g | |

| Chloramphenicol | C11H12Cl2N2O5 | 500 mg |

| Thiabendazole | C10H7N3S | 1 mg |

| Cycloheximide | C15H23NO4 | 250 mg |

| Distilled water | H2O | 1 L |

- (14)

- Oatmeal Dodine agar (ODA).

| Reagents and Chemicals | Chemical Formula (If Applicable) | Quantity |

| Oatmeal infusion | 20.0 g | |

| Dodine (N-dodecylguanidine monoacetate) | C15H33N3O2 | 550 mg |

| Chlortetracycline | C22H23ClN2O8 | 5 mg |

| Crystal violet | C25N3H30Cl | 10 mg |

| Agar | 20.0 g | |

| Distilled water | H2O | 1 L |

- (15)

- Sabouraud-2-Glucose agar (S2GA).

| Reagents and Chemicals | Chemical Formula (If Applicable) | Quantity |

| Glucose | C6H12O6 | 20.0 g |

| Peptone | 10.0 g | |

| Streptomycin sulphate | C42H84N14O36S3 | 600 mg |

| Tetracycline | C22H24N2O8 | 50 mg |

| Cycloheximide | C15H23NO4 | 50 mg |

| Dodine (N-dodecylguanidine monoacetate) | C15H33N3O2 | 100 mg |

| Agar | 12.0 g | |

| Distilled water | H2O | 1 L |

- (16)

- Purpureocillium lilacinum medium.

| Reagents and Chemicals | Chemical formula (If Applicable) | Quantity |

| Potato dextrose agar | 39.0 g | |

| Sodium chloride | NaCl | 10–30 g |

| Tergitol | 1 g | |

| Pentachloronitrobenzene | C6Cl5NO2 | 500 mg |

| Benomyl | C14H18N4O3 | 500 mg |

| Streptomycin sulphate | C42H84N14O36S3 | 100 mg |

| Chlortetracycline hydrochloride | C22H24Cl2N2O8 | 50 mg |

| Distilled water | H2O | 1 L |

- (17)

- Lecanicillium-specific medium.

| Reagents and Chemicals | Chemical Formula (If Applicable) | Quantity |

| L-sorbose | C6H12O6 | 2 g |

| L-asparagine | C4H8N2O3 | 2 g |

| Dipotassium phosphate | K2HPO4 | 1 g |

| Potassium chloride | KCl | 1 g |

| Magnesium sulfate heptahydrate | MgSO4.7H2O | 0.5 g |

| Ferric-sodium salt (FeNaEDTA) | C10H12N2O8FeNa | 0.01 g |

| Agar | 20 g | |

| Streptomycin sulphate | C42H84N14O36S3 | 0.3 g |

| Chlortetracycline hydrochloride | C22H24Cl2N2O8 | 0.05 g |

| Pentachloronitrobenzene | C6Cl5NO2 | 0.8 g |

| Borax | NaB4O7.10H2O | 1 g |

| Distilled water | 1 L |

References

- Ruiu, L. Microbial Biopesticides in Agroecosystems. Agronomy 2018, 8, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glare, T.; Caradus, J.; Gelernter, W.; Jackson, T.; Keyhani, N.; Köhl, J.; Marrone, P.; Morin, L.; Stewart, A. Have biopesticides come of age? Trends Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marx-Stoelting, P.; Pfeil, R.; Solecki, R.; Ulbrich, B.; Grote, K.; Ritz, V.; Banasiak, U.; Heinrich-Hirsch, B.; Moeller, T.; Chahoud, I.; et al. Assessment strategies and decision criteria for pesticides with endocrine disrupting properties relevant to humans. Reprod. Toxicol. 2011, 31, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, L.; Gonçalves, F.; Oliveira, I.; Torres, L.; Marques, G. Insect-associated fungi from naturally mycosed vine mealybug Planococcus ficus (Signoret) (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae). Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2018, 28, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.; Marques, G. Fusarium, an Entomopathogen—A Myth or Reality? Pathogens 2018, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, L.; Oliveira, I.; Raimundo, F.; Torres, L.; Marques, G. Soil chemical properties barely perturb the abundance of entomopathogenic Fusarium oxysporum: A case study using a generalized linear mixed model for microbial pathogen occurrence count data. Pathogens 2018, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.; Oliveira, I.; Torres, L.; Marques, G. Entomopathogenic fungi in Portuguese vineyards soils: Suggesting a ‘Galleria-Tenebrio-bait method’ as bait-insects Galleria and Tenebrio significantly underestimate the respective recoveries of Metarhizium (robertsii) and Beauveria (bassiana). MycoKeys 2018, 38, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.; Bohra, N.; Singh, R.K.; Marques, G. Potential of Entomopathogenic Bacteria and Fungi. In Microbes for Sustainable Insect Pest Management: An Eco-friendly Approach—Volume 1; Khan, M.A., Ahmad, W., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 115–149. [Google Scholar]

- Azizoglu, U.; Jouzani, G.S.; Yilmaz, N.; Baz, E.; Ozkok, D. Genetically modified entomopathogenic bacteria, recent developments, benefits and impacts: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 734, 139169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faria, M.R.d.; Wraight, S.P. Mycoinsecticides and Mycoacaricides: A comprehensive list with worldwide coverage and international classification of formulation types. Biol. Control. 2007, 43, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, E.H.; Jaronski, S.T.; Hajek, A.E. Virulence of commercialized fungal entomopathogens against asian longhorned beetle (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae). J. Insect Sci. 2020, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papagiannoulis, A.; Mathiopoulos, K.D.; Mossialos, D. Molecular detection of the entomopathogenic bacterium Pseudomonas entomophila using PCR. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 50, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, S.; Hendriksen, N.B.; Melin, P.; Lundstrom, J.O.; Sundh, I. Chromosome-Directed PCR-based detection and quantification of Bacillus cereus group members with focus on B. thuringiensis Serovar israelensis active against nematoceran larvae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 81, 4894–4903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Schneider, S.; Widmer, F.; Jacot, K.; Kölliker, R.; Enkerli, J. Spatial distribution of Metarhizium clade 1 in agricultural landscapes with arable land and different semi-natural habitats. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2012, 52, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfora, L.; Malusà, E.; Tkaczuk, C.; Tartanus, M.; Łabanowska, B.H.; Pinzari, F. Development of a method for detection and quantification of B. brongniartii and B. bassiana in soil. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrido-Jurado, I.; Landa, B.B.; Quesada-Moraga, E. Detection and quantification of the entomopathogenic fungal endophyte Beauveria bassiana in plants by nested and quantitative PCR. In Microbial-Based Biopesticides: Methods and Protocols; Glare, T.R., Moran-Diez, M.E., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon, A.C.; Glare, T.R.; Ridgway, H.J.; Mendoza-Mendoza, A.; Holyoake, A.; Godsoe, W.K.; Bufford, J.L. Detection of the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana in the rhizosphere of wound-stressed zea mays plants. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiu, L. Insect Pathogenic Bacteria in Integrated Pest Management. Insects 2015, 6, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godjo, A.; Afouda, L.; Baimey, H.; Decraemer, W.; Willems, A. Molecular diversity of Photorhabdus and Xenorhabdus bacteria, symbionts of Heterorhabditis and Steinernema nematodes retrieved from soil in Benin. Arch. Microbiol. 2018, 200, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, M.R.H.; Becher, S.A.; Young, S.D.; Nelson, T.L.; Glare, T.R. Yersinia entomophaga sp. nov., isolated from the New Zealand grass grub Costelytra zealandica. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2011, 61, 844–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vodovar, N.; Vinals, M.; Liehl, P.; Basset, A.; Degrouard, J.; Spellman, P.; Boccard, F.; Lemaitre, B. Drosophila host defense after oral infection by an entomopathogenic Pseudomonas species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 11414–11419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, P.A.W.; Hirose, E.; Aldrich, J.R. Toxicity of Chromobacterium subtsugae to southern green stink bug (Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) and corn rootworm (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2007, 100, 680–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahly, D.P.; Takefman, D.M.; Livasy, C.A.; Dingman, D.W. Selective medium for quantitation of Bacillus popilliae; in soil and in commercial spore powders. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1992, 58, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stahly, D.P.; Andrews, R.E.; Yousten, A.A. The genus Bacillus—Insect pathogens. In The Prokaryotes: Volume 4: Bacteria: Firmicutes, Cyanobacteria; Dworkin, M., Falkow, S., Rosenberg, E., Schleifer, K.-H., Stackebrandt, E., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 563–608. [Google Scholar]

- Koppenhöfer, A.M.; Jackson, T.; Klein, M.G. Bacteria for Use Against Soil-Inhabiting Insects; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 129–149. [Google Scholar]

- St. Julian, G.J.; Pridham, T.G.; Hall, H.H. Effect of diluents on viability of Popillia japonica Newman larvae, Bacillus popilliae Dutky, and Bacillus lentimorbus Dutky. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1963, 5, 440–450. [Google Scholar]

- Dingman, D.W.; Stahly, D.P. Medium Promoting Sporulation of Bacillus larvae and Metabolism of Medium Components. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1983, 46, 860–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger, L.; Franken, E.; Schnetter, W. Bacillus popilliae var melolontha H1, a pathogen for the May beetles, Melolontha spp. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Workshop on Microbial Control of Soil Dwelling Pests, Lincoln, New Zealand, 21–23 February 1996; Jackson, T.A., Glare, T.R., Eds.; AgResearch: Lincoln, New Zealand, 1996; pp. 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, R.J. A method for isolating milky disease, Bacillus popilliae var. rhopaea, spores from the soil. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1977, 30, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Callaghan, M.; Jackson, T.A. Isolation and enumeration of Serratia entomophila—a bacterial pathogen of the New Zealand grass grub, Costelytra zealandica. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1993, 75, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr, M.P.; Grimont, P.A.; Grimont, F.; Starr, P.B. Caprylate-thallous agar medium for selectively isolating Serratia and its utility in the clinical laboratory. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1976, 4, 270. [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz, D.M.; Lee, W.S. A selective medium for the isolation and identification of Serratia marcescens. In Abstracts of the Annual Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology; American Society for Microbiology: Washington, DC, USA, 1973; Volume 105. [Google Scholar]

- Kalfon, A.; Larget-Thiéry, I.; Charles, J.-F.; de Barjac, H. Growth, sporulation and larvicidal activity of Bacillus sphaericus. Eur. J. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1983, 18, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, T.W.; Garczynski, S.F. Chapter III—Isolation, culture, preservation, and identification of entomopathogenic bacteria of the Bacilli. In Manual of Techniques in Invertebrate Pathology, 2nd ed.; Lacey, L.A., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 75–99. [Google Scholar]

- Lacey, L.A.; Grzywacz, D.; Shapiro-Ilan, D.I.; Frutos, R.; Brownbridge, M.; Goettel, M.S. Insect pathogens as Biological Control agents: Back to the future. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2015, 132, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza-Menchaca, T.; Singh, R.K.; Quiroz-Chávez, J.; García-Pérez, L.M.; Rodríguez-Mora, N.; Soto-Luna, M.; Gastélum-Contreras, G.; Vanzzini-Zago, V.; Sharma, L.; Quiroz-Figueroa, F.R. First demonstration of clinical Fusarium strains causing cross-kingdom infections from humans to plants. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos, C.G.F.; Sousa, S.; Salvação, J.; Sharma, L.; Soares, R.; Manso, J.; Nóbrega, M.; Lopes, A.; Soares, S.; Aranha, J.; et al. Environmentally safe strategies to control the European Grapevine Moth, Lobesia botrana (Den. & Schiff.) in the Douro Demarcated Region. Cienc. Tec. Vitivinic. 2013, 28, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Domsch, K.H.; Gams, W.; Anderson, T.H. Compendium of Soil Fungi, 2nd ed.; IHW-Verlag and Verlagsbuchhandlung: Eching, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Humber, R.A. Chapter VI—Identification of entomopathogenic fungi. In Manual of Techniques in Invertebrate Pathology, 2nd Ed.; Lacey, L.A., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 151–187. [Google Scholar]

- Yurkov, A.; Guerreiro, M.A.; Sharma, L.; Carvalho, C.; Fonseca, Á. Correction: Multigene assessment of the species boundaries and sexual status of the basidiomycetous yeasts Cryptococcus flavescens and C. terrestris (Tremellales). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0126996. [Google Scholar]

- Inglis, G.D.; Enkerli, J.; Goettel, M.S. Chapter VII—Laboratory techniques used for entomopathogenic fungi: Hypocreales. In Manual of Techniques in Invertebrate Pathology, 2nd ed.; Lacey, L.A., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 189–253. [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, Y.; Portal, O.; Lysøe, E.; Meyling, N.V.; Klingen, I. Diversity and abundance of Beauveria bassiana in soils, stink bugs and plant tissues of common bean from organic and conventional fields. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2017, 150, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, B.-D.; Liu, X.-Z. Occurrence and diversity of insect-associated fungi in natural soils in China. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2008, 39, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, I.; Pereira, J.A.; Lino-Neto, T.; Bento, A.; Baptista, P. Fungal diversity associated to the olive moth, Prays oleae Bernard: A survey for potential entomopathogenic fungi. Microb. Ecol. 2012, 63, 964–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, I.; Pereira, J.A.; Quesada-Moraga, E.; Lino-Neto, T.; Bento, A.; Baptista, P. Effect of soil tillage on natural occurrence of fungal entomopathogens associated to Prays oleae Bern. Sci. Hortic. 2013, 159, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, M.; Gómez-Jiménez, M.I.; Ortiz, V.; Vega, F.E.; Kramer, M.; Parsa, S. Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae endophytically colonize cassava roots following soil drench inoculation. Biol. Control 2016, 95, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posadas, J.B.; Comerio, R.M.; Mini, J.I.; Nussenbaum, A.L.; Lecuona, R.E. A novel dodine-free selective medium based on the use of cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) to isolate Beauveria bassiana, Metarhizium anisopliae sensu lato and Paecilomyces lilacinus from soil. Mycologia 2012, 104, 974–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.D.; Hocking, A.D.; Pitt, J.I. Dichloran-rose bengal medium for enumeration and isolation of molds from foods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1979, 37, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veen, K.H.; Ferron, P. A selective medium for the isolation of Beauveria tenella and of Metarrhizium anisopliae. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1966, 8, 268–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, A.R.; Osborne, L.S.; Ferguson, V.M. Selective isolation of the entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae from an artificial potting medium. Fla. Entomol. 1986, 69, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneh, B. Isolation of Metarhizium anisopliae from insects on an improved selective medium based on wheat germ. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1991, 58, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Milner, R.J.; McRae, C.F.; Lutton, G.G. The use of dodine in selective media for the isolation of Metarhizium spp. from soil. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1993, 62, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, D.E.N.; Dettenmaier, S.J.; Fernandes, É.K.K.; Roberts, D.W. Susceptibility of Metarhizium spp. and other entomopathogenic fungi to dodine-based selective media. Biocontrol. Sci. Technol. 2010, 20, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, É.K.K.; Keyser, C.A.; Rangel, D.E.N.; Foster, R.N.; Roberts, D.W. CTC medium: A novel dodine-free selective medium for isolating entomopathogenic fungi, especially Metarhizium acridum, from soil. Biol. Control. 2010, 54, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Domínguez, C.; Cerroblanco-Baxcajay, M.d.L.; Alvarado-Aragón, L.U.; Hernández-López, G.; Guzmán-Franco, A.W. Comparison of the relative efficacy of an insect baiting method and selective media for diversity studies of Metarhizium species in the soil. Biocontrol. Sci. Technol. 2016, 26, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ormond, E.L.; Thomas, A.P.; Pugh, P.J.; Pell, J.K.; Roy, H.E. A fungal pathogen in time and space: The population dynamics of Beauveria bassiana in a conifer forest. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2010, 74, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Clifton, E.H.; Jaronski, S.T.; Hodgson, E.W.; Gassmann, A.J. Abundance of soil-borne entomopathogenic fungi in organic and conventional fields in the midwestern usa with an emphasis on the effect of herbicides and fungicides on fungal persistence. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Jurado, I.; Fernandez-Bravo, M.; Campos, C.; Quesada-Moraga, E. Diversity of entomopathogenic Hypocreales in soil and phylloplanes of five Mediterranean cropping systems. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2015, 130, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, E.H.; Jaronski, S.T.; Coates, B.S.; Hodgson, E.W.; Gassmann, A.J. Effects of endophytic entomopathogenic fungi on soybean aphid and identification of Metarhizium isolates from agricultural fields. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0194815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strasser, H.; Forer, A.; Schinner, F. Development of media for the selective isolation and maintenance of Beauveria brongniartii. In Microbial Control of Soil Dwelling Pests; Jackson, T.A., Glare, T.R., Eds.; AgResearch: Lincoln, New Zealand, 1996; pp. 125–130. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, S.; Kessler, P.; Schweizer, C. Distribution of insect pathogenic soil fungi in Switzerland with special reference to Beauveria brongniartii and Metharhizium anisopliae. BioControl 2003, 48, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enkerli, J.; Widmer, F.; Keller, S. Long-term field persistence of Beauveria brongniartii strains applied as biocontrol agents against European cockchafer larvae in Switzerland. Biol. Control. 2004, 29, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, P.; Enkerl, J.; Schweize, C.; Keller, S. Survival of Beauveria brongniartii in the soil after application as a biocontrol agent against the European cockchafer Melolontha melolontha. BioControl 2004, 49, 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyling, N.V.; Eilenberg, J. Isolation and characterisation of Beauveria bassiana isolates from phylloplanes of hedgerow vegetation. Mycol. Res. 2006, 110, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Świergiel, W.; Meyling, N.V.; Porcel, M.; Rämert, B. Soil application of Beauveria bassiana GHA against apple sawfly, Hoplocampa testudinea (Hymenoptera: Tenthredinidae): Field mortality and fungal persistence. Insect. Sci. 2016, 23, 854–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Rodríguez, D.; Sánchez-Peña, S.R. Recovery of endophytic Beauveria bassiana on a culture medium based on cetyltrimethylammonium bromide. Biocontrol. Sci. Technol. 2016, 26, 570–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.J.; Kannwischer-Mitchell, M.E.; Dickson, D.W. A semi-selective medium for the isolation of Paecilomyces lilacinus from soil. J. Nematol. 1987, 19, 255–256. [Google Scholar]

- Goettel, M.S.; Inglis, G.D. Chapter V-3—Fungi: Hyphomycetes. In Manual of Techniques in Insect Pathology; Lacey, L.A., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1997; pp. 213–249. [Google Scholar]

- Kope, H.; Alfaro, R.; Lavallee, R. Virulence of the entomopathogenic fungus Lecanicillium (Deuteromycota: Hyphomycetes) to Pissodes strobi (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Can. Entomol. 2006, 138, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Peng, D.-L.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, X.-L.; Zhang, Z.-R.; Zhao, J.-J.; Wu, Y.-H. Persistence and Viability of Lecanicillium lecanii in Chinese Agricultural Soil. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0138337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheepmaker, J.W.A.; Butt, T.M. Natural and released inoculum levels of entomopathogenic fungal biocontrol agents in soil in relation to risk assessment and in accordance with EU regulations. Biocontrol. Sci. Technol. 2010, 20, 503–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, F.E.; Meyling, N.V.; Luangsa-ard, J.J.; Blackwell, M. Fungal Entomopathogens. In Insect Pathology, 2nd ed.; Vega, F.E., Kaya, H.K., Eds.; Academic Press Elsevier Inc.: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 171–220. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, G. The ‘Galleria bait method’ for detection of entomopathogenic fungi in soil. J. Appl. Entomol. 1986, 102, 213–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, D.; Hay, D.; Reid, A.P. Sampling and occurrence of entomopathogenic fungi and nematodes in UK soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 1997, 5, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, C.W.; Barker, G.M. Generalist entomopathogens as biological indicators of deforestation and agricultural land use impacts on Waikato soils. N. Zeal. J. Ecol. 1998, 22, 189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Bidochka, M.J.; Kasperski, J.E.; Wild, G.A.M. Occurrence of the entomopathogenic fungi Metarhizium anisopliae and Beauveria bassiana in soils from temperate and near-northern habitats. Can. J. Bot. 1998, 76, 1198–1204. [Google Scholar]

- Hummel, R.L.; Walgenbach, J.F.; Barbercheck, M.E.; Kennedy, G.G.; Hoyt, G.D.; Arellano, C. Effects of production practices on soil-borne entomopathogens in Western North Carolina vegetable systems. Environ. Entomol. 2002, 31, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali-Shtayeh, M.S.; Mara’i, A.-B.B.M.; Jamous, R.M. Distribution, occurrence and characterization of entomopathogenic fungi in agricultural soil in the Palestinian area. Mycopathologia 2003, 156, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asensio, L.; Carbonell, T.; Lopez Jimenez, J.; López Llorca, L. Entomopathogenic fungi in soils from Alicante province. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2003, 1, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyling, N.V.; Eilenberg, J. Occurrence and distribution of soil borne entomopathogenic fungi within a single organic agroecosystem. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2006, 113, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesada-Moraga, E.; Navas-Cortés, J.A.; Maranhao, E.A.A.; Ortiz-Urquiza, A.; Santiago-Álvarez, C. Factors affecting the occurrence and distribution of entomopathogenic fungi in natural and cultivated soils. Mycol. Res. 2007, 111, 947–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.-D.; Yu, H.-y.; Chen, A.J.; Liu, X.-Z. Insect-associated fungi in soils of field crops and orchards. Crop. Protect. 2008, 27, 1421–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, R.; Barbercheck, M.E. Soil management effects on entomopathogenic fungi during the transition to organic agriculture in a feed grain rotation. Biol. Control. 2009, 51, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevim, A.; Demir, I.; Höfte, M.; Humber, R.A.; Demirbag, Z. Isolation and characterization of entomopathogenic fungi from hazelnut-growing region of Turkey. BioControl 2009, 55, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.J.; Rehner, S.A.; Bruck, D.J. Diversity of rhizosphere associated entomopathogenic fungi of perennial herbs, shrubs and coniferous trees. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2011, 106, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñiz-Reyes, E.; Guzmán-Franco, A.W.; Sánchez-Escudero, J.; Nieto-Angel, R. Occurrence of entomopathogenic fungi in tejocote (Crataegus mexicana) orchard soils and their pathogenicity against Rhagoletis pomonella. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 117, 1450–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-González, V.H.; Guzmán-Franco, A.W.; Alatorre-Rosas, R.; Hernández-López, J.; Hernández-López, A.; Carrillo-Benítez, M.G.; Baverstock, J. Specific diversity of the entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria and Metarhizium in Mexican agricultural soils. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2014, 119, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medo, J.; Michalko, J.; Medová, J.; Cagáň, Ľ. Phylogenetic structure and habitat associations of Beauveria species isolated from soils in Slovakia. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2016, 140, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Salas, A.; Alonso-Díaz, M.A.; Alonso-Morales, R.A.; Lezama-Gutiérrez, R.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, J.C.; Cervantes-Chávez, J.A. Acaricidal activity of Metarhizium anisopliae isolated from paddocks in the Mexican tropics against two populations of the cattle tick Rhipicephalus microplus. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2017, 31, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, H.; Wickings, K. Soil ecological responses to pest management in golf turf vary with management intensity, pesticide identity, and application program. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2017, 246, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirubakaran, S.A.; Abdel-Megeed, A.; Senthil-Nathan, S. Virulence of selected indigenous Metarhizium pingshaense (Ascomycota: Hypocreales) isolates against the rice leaffolder, Cnaphalocrocis medinalis (Guenèe) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). Physiol. Mol. Plant. Pathol. 2018, 101, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Peña, S.R.; Lara, J.S.-J.; Medina, R.F. Occurrence of entomopathogenic fungi from agricultural and natural ecosystems in Saltillo, México, and their virulence towards thrips and whiteflies. J. Insect Sci. 2011, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinwender, B.M.; Enkerli, J.; Widmer, F.; Eilenberg, J.; Thorup-Kristensen, K.; Meyling, N.V. Molecular diversity of the entomopathogenic fungal Metarhizium community within an agroecosystem. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2014, 123, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera Sammaritano, J.A.; López Lastra, C.C.; Leclerque, A.; Vazquez, F.; Toro, M.E.; D’Alessandro, C.P.; Cuthbertson, A.G.S.; Lechner, B.E. Control of Bemisia tabaci by entomopathogenic fungi isolated from arid soils in Argentina. Biocontrol. Sci. Technol. 2016, 26, 1668–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imoulan, A.; Alaoui, A.; El Meziane, A. Natural occurrence of soil-borne entomopathogenic fungi in the moroccan endemic forest of Argania spinosa and their pathogenicity to Ceratitis capitata. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 27, 2619–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyser, C.A.; De Fine Licht, H.H.; Steinwender, B.M.; Meyling, N.V. Diversity within the entomopathogenic fungal species Metarhizium flavoviride associated with agricultural crops in Denmark. BMC Microbiol. 2015, 15, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medo, J.; Cagáň, Ľ. Factors affecting the occurrence of entomopathogenic fungi in soils of Slovakia as revealed using two methods. Biol. Control. 2011, 59, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkaczuk, C.; Król, A.; Majchrowska-Safaryan, A.; Nicewicz, Ł. The occurrence of entomopathogenic fungi in soils from fields cultivated in a conventional and organic system. J. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 15, 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Kepler, R.M.; Ugine, T.A.; Maul, J.E.; Cavigelli, M.A.; Rehner, S.A. Community composition and population genetics of insect pathogenic fungi in the genus Metarhizium from soils of a long-term agricultural research system. Environ. Microbiol. 2015, 17, 2791–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Domínguez, C.; Guzmán-Franco, A.W. Species diversity and population dynamics of entomopathogenic fungal species in the genus Metarhizium—a spatiotemporal Study. Microb. Ecol. 2017, 74, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, A.I.; Siva-Jothy, M.T. DensitY-dependent prophylaxis in the mealworm beetle Tenebrio molitor L. (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae): Cuticular melanization is an indicator of investment in immunity. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2000, 267, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubovskiy, I.M.; Whitten, M.M.A.; Kryukov, V.Y.; Yaroslavtseva, O.N.; Grizanova, E.V.; Greig, C.; Mukherjee, K.; Vilcinskas, A.; Mitkovets, P.V.; Glupov, V.V.; et al. More than a colour change: Insect melanism, disease resistance and fecundity. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2013, 280, 20130584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryukov, V.Y.; Tyurin, M.V.; Tomilova, O.G.; Yaroslavtseva, O.N.; Kryukova, N.A.; Duisembekov, B.A.; Tokarev, Y.S.; Glupov, V.V. Immunosuppression of insects by the venom of Habrobracon hebetor increases the sensitivity of bait method for the isolation of entomopathogenic fungi from soils. Biol. Bull. 2017, 44, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vänninen, I. Distribution and occurrence of four entomopathogenic fungi in Finland: Effect of geographical location, habitat type and soil type. Mycol. Res. 1996, 100, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, W.O.H.; Thomsen, L.; Eilenberg, J.; Boomsma, J.J. Diversity of entomopathogenic fungi near leaf-cutting ant nests in a neotropical forest, with particular reference to Metarhizium anisopliae var. anisopliae. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2004, 85, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oddsdottir, E.S.; Nielsen, C.; Sen, R.; Harding, S.; Eilenberg, J.; Halldorsson, G. Distribution patterns of soil entomopathogenic and birch symbiotic ectomycorrhizal fungi across native woodlandand degraded habitats in Iceland. Icel. Agric. Sci. 2010, 23, 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Meyling, N.V.; Schmidt, N.M.; Eilenberg, J. Occurrence and diversity of fungal entomopathogens in soils of low and high Arctic Greenland. Polar Biol. 2012, 35, 1439–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingen, I.; Eilenberg, J.; Meadow, R. Effects of farming system, field margins and bait insect on the occurrence of insect pathogenic fungi in soils. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2002, 91, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goble, T.A.; Dames, J.F.; Hill, M.P.; Moore, S.D. The effects of farming system, habitat type and bait type on the isolation of entomopathogenic fungi from citrus soils in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. BioControl 2010, 55, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudeen, M.L.; Jaronski, S.T.; Petzold-Maxwell, J.L.; Gassmann, A.J. Entomopathogenic fungi in cornfields and their potential to manage larval western corn rootworm Diabrotica virgifera virgifera. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2013, 114, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ownley, B.H.; Griffin, M.R.; Klingeman, W.E.; Gwinn, K.D.; Moulton, J.K.; Pereira, R.M. Beauveria bassiana: Endophytic colonization and plant disease control. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2008, 98, 267–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, O.; Sushida, H.; Higashi, Y.; Iida, Y. Epiphytic and endophytic colonisation of tomato plants by the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana strain GHA. Mycology 2020, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyling, N.V.; Pilz, C.; Keller, S.; Widmer, F.; Enkerli, J. Diversity of Beauveria spp. isolates from pollen beetles Meligethes aeneus in Switzerland. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2012, 109, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehner, S.A.; Posada, F.; Buckley, E.P.; Infante, F.; Castillo, A.; Vega, F.E. Phylogenetic origins of African and neotropical Beauveria bassiana s.l. pathogens of the coffee berry borer, Hypothenemus hampei. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2006, 93, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyling, N.V.; Lubeck, M.; Buckley, E.P.; Eilenberg, J.; Rehner, S.A. Community composition, host range and genetic structure of the fungal entomopathogen Beauveria in adjoining agricultural and seminatural habitats. Mol. Ecol. 2009, 18, 1282–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bischoff, J.F.; Rehner, S.A.; Humber, R.A. A multilocus phylogeny of the Metarhizium anisopliae lineage. Mycologia 2009, 101, 512–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, J.M.; Zanardo, A.B.R.; da Silva Lopes, M.; Delalibera, I.; Rehner, S.A. Phylogenetic diversity of Brazilian Metarhizium associated with sugarcane agriculture. BioControl 2015, 60, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spatafora, J.W.; Sung, G.H.; Sung, J.M.; Hywel-Jones, N.L.; White, J.F. Phylogenetic evidence for an animal pathogen origin of ergot and the grass endophytes. Mol. Ecol. 2007, 16, 1701–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepler, R.M.; Rehner, S.A. Genome-assisted development of nuclear intergenic sequence markers for entomopathogenic fungi of the Metarhizium anisopliae species complex. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2013, 13, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enkerli, J.; Widmer, F.; Gessler, C.; Keller, S. Strain-specific microsatellite markers in the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria brongniartii. Mycol. Res. 2001, 105, 1079–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehner, S.A.; Buckley, E.P. Isolation and characterization of microsatellite loci from the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana (Ascomycota: Hypocreales). Mol. Ecol. Notes 2003, 3, 409–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enkerli, J.; Widmer, F. Molecular ecology of fungal entomopathogens: Molecular genetic tools and their applications in population and fate studies. BioControl 2010, 55, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goble, T.A.; Costet, L.; Robene, I.; Nibouche, S.; Rutherford, R.S.; Conlong, D.E.; Hill, M.P. Beauveria brongniartii on white grubs attacking sugarcane in South Africa. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2012, 111, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enkerli, J.; Kölliker, R.; Keller, S.; Widmer, F. Isolation and characterization of microsatellite markers from the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2005, 5, 384–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oulevey, C.; Widmer, F.; Kölliker, R.; Enkerli, J. An optimized microsatellite marker set for detection of Metarhizium anisopliae genotype diversity on field and regional scales. Mycol. Res. 2009, 113, 1016–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyling, N.V.; Thorup-Kristensen, K.; Eilenberg, J. Below- and aboveground abundance and distribution of fungal entomopathogens in experimental conventional and organic cropping systems. Biol. Control. 2011, 59, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korosi, G.A.; Wilson, B.A.L.; Powell, K.S.; Ash, G.J.; Reineke, A.; Savocchia, S. Occurrence and diversity of entomopathogenic fungi (Beauveria spp. and Metarhizium spp.) in Australian vineyard soils. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2019, 164, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyling, N.V.; Eilenberg, J. Ecology of the entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae in temperate agroecosystems: Potential for conservation biological control. Biol. Control. 2007, 43, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bacteria | Target Pest | Crops | PRODUCT (Company, Country) |

|---|---|---|---|

| B. acillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki | Lepidoptera | Row crops, forests, orchards, forests turfs | CRYMAX (Certis, USA) |

| DELIVER (Certis, USA) | |||

| JAVELIN WG (Certis, USA) | |||

| COSTAR JARDIN; COSTAR WG (Mitsui AgriScience International NV, Belgium) | |||

| LEPINOX PLUS (CBC, Europe) | |||

| BACTOSPEINE JARDIN EC (Duphar BV, The Netherlands) | |||

| DOLPHIN (Andermatt Biocontrol, Switzerland) | |||

| BMP 123 (Becker, USA) | |||

| DIPEL DF (Valent Biosciences, USA) | |||

| LEAP (Valent Biosciences, USA) | |||

| FORAY 48 B (Valent Biosciences, USA) | |||

| B. thuringiensis subsp. aizawai | Lepidoptera | Row crops, orchards | CRYMAX (Certis, USA) |

| AGREE 50 WG (Certis, USA) | |||

| XENTARI (Valent Biosciences, USA) | |||

| FLORBAC (Bayer, Germany) | |||

| B. thuringiensis subsp. tenebrionis | Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae | Potatoes, tomatoes, eggplant, elm trees | TRIDENT (Certis USA) |

| NOVODOR FC (Valent Biosciences, USA) | |||

| B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis | Diptera | Diverse lentic and lotic aquatic habitats | AQUABAC DF3000, (Becker Microbial Products Inc, USA) |

| VECTOPRIME (Valent Biosciences, USA) | |||

| TEKNAR (Valent Biosciences, USA) | |||

| VECTOBAC (Valent Biosciences, USA) | |||

| BACTIMOS (Valent Biosciences, USA) | |||

| SOLBAC (Andermatt Biocontrol, Switzerland) | |||

| Lysinibacillus sphaericus | Diptera: Culicidae | Lentic aquatic habitats | VECTOLEX (Valent Biosciences, USA) |

| Serratia entomophila | Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae | Pastures | BIOSHIELD GRASS GRUB (Biostart, New Zealand) |

| Paenibacillus popilliae | Japanese beetle larvae/grub | Lawns, flowers, mulch beds, gardens | MILKY SPORE POWDER (St. Gabriel Organics, USA) |

| Fungi | Target Pest | Crop | Product and Company |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beauveria bassiana sensu lato | Psyllids, whiteflies, thrips, aphids, mites | crops | BOTE GHA (Certis, USA) |

| Flies, mites, thrips, leafhoppers, and weevils | cotton, glasshouse crops | NATURALIS (Troy Biosciences, USA) | |

| Coffee berry borer | coffee | CONIDIA (AgroEvo, Germany) | |

| Whiteflies, aphids, thrips | field crops | MYCOTROL (Bioworks, USA) | |

| Whiteflies, aphids, thrips | field crops | BOTANIGRAD (Bioworks, USA) | |

| Corn borer | maize | OSTRINIL (Arysta Lifescience, France) | |

| Spotted mite, eucalyptus weevil, coffee borer, and whitefly | crops | BOVERIL (Koppert, The Netherlands) | |

| Flies | BALANCE (Rincon-Vitova Insectaries, USA) | ||

| As soil treatment | crops | BEAUVERIA BASSIANA PLUS, (BuildASoil, USA) | |

| Whitefly | peppers, tomatoes, potatoes, eggplants | BEA-SIN (Agrobionsa, Mexico) | |

| B. brongniartii | May beetle | forests, vegetables, fruits, grasslands | MELOCONT PILZGERSTE (Samen-schwarzenberger, Austria) |

| Cockchafer larvae | Fruits, Meadows | BEAUPRO (Andermatt Biocontrol, Switzerland) | |

| Scarabs beetle larvae | sugarcane | BETEL (Natural Plant Protection, France) | |

| Cockchafer | fruits, Meadows | BEAUVERIA-SCHWEIZER (Eric Schweizer, Switzerland) | |

| Metarhizium anisopliae sensu lato | Sugar cane root leafhopper | sugarcane | METARRIL WP (Koppert, The Netherlands) |

| Cockroaches | houses | BIO-PATH (EcoScience, USA) | |

| Vine weevils, sciarid flies, wireworms and thrips pupae | glasshouse, ornamental crops | BIO 1020 (Bayer, Germany) | |

| White grubs | sugarcane | BIOCANE (BASF, Australia) | |

| termites | BIOBLAST (Paragon, USA) | ||

| Black vine weevil, strawberry root weevil, thrips | stored grains and crops | MET-52 (Novozymes, USA) | |

| Pepper weevil | chili and bell peppers | META-SIN (Agrobionsa, Mexico) | |

| M. acridum | Locusts and grasshoppers | crops | GREEN GUARD (BASF, Australia) |

| M. frigidum | Scarab larvae | crops | BIOGREEN (BASF, Australia) |

| M. brunneum | Wireworms | potato and asparagus crops | ATTRACAP (Biocare, Germany) |

| Cordyceps fumosorosea | Whiteflies | glasshouse crops | PREFERAL WG (Biobest, Belgium) |

| Aphids, Citrus psyllid, spider mite, thrips, whitefly | wide range of crops | PFR-97 20% WDG (Certis, USA) | |

| Whitefly | Peppers, tomatoes, potatoes, eggplants | BEA-SIN (Agrobionsa, Mexico) | |

| Cotton bullworm, Citrus psyllid | Field crops | CHALLENGER (Koppert, The Netherlands) | |

| Lecanicillium longisporum | Aphids | crops | VERTALEC (Koppert, The Netherlands) |

| Whiteflies, thrips | crops | MYCOTAL (Koppert, The Netherlands) | |

| L. lecanii | Aphids | peppers, tomatoes, potatoes, eggplants | VERTI-SIN (Agrobionsa, Mexico) |

| Entomopathogenic Fungi | Soil Habitat Type | Medium for Soil Suspension Culture | Insect Baiting a | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beauveria bassiana sensu lato | Organically managed farm and hedgerows with hawthorn, poplar, nettles, in Bakkegården, Denmark | n/a | GM | [80] |

| Conventional and organic corn field and soybean field; and field margins with grass strips in Iowa, USA | Appendix A, Medium 14 (supplemented with 0.62 gL−1 dodine) | GM | [57] | |

| Agricultural habitat and natural habitat, Southern Ontario and the Kawartha Lakes region, Canada | n/a | GM | [76] | |

| Cultivated habitats (olive and stone-fruit crops, horticultural crops, cereals crops, leguminous crops, and sunflower); and natural habitats (natural forests, pastures, riverbanks, and desert areas) in Spain and the Canary and the Balearic Archipelagos | n/a | GM | [81] | |

| Three conventional citrus farms and three organic citrus farms in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa | n/a | C. capitata; T. leucotreta; GM | [109] | |

| Cornfields, Iowa, USA | n/a | D. virgifera virgifera; TM; GM | [110] | |

| Tejocote orchard soils, Mexico | n/a | GM | [86] | |

| Solovakian crop fields, meadows, hedgerows, and forests | Appendix A, Medium 15 | GM | [88,97] | |

| Darmstadt surroundings, Germany | n/a | GM | [73] | |

| Fields in east, north, central and south west of Switzerland | Appendix A, Medium 15 | GM | [61] | |

| Argan forests in Morocco | Appendix A, Medium 15 | GM | [95] | |

| Natural and cultivated soils, Finland | n/a | A. aedilis; T. castaneum; GM; TM | [104] | |

| Native woodland soils, Iceland | n/a | GM; TM | [106] | |

| Field crop and hedgerows, Årslev, Denmark | n/a | GM | [126] | |

| Soils from Dylas plant community, Greenland | n/a | GM | [107] | |

| Vineyard soils and hedgerows, Douro wine region, Portugal | n/a | GM; TM | [7] | |

| Vineyards in the states of New South Wales and Victoria, Australia | Appendix A, Medium 9 (supplemented with 0.2 g/L dodine, 0.1 g/L chloramphenicol, and 0.05 g/L streptomycin sulphate); Appendix A, Medium 15 | TM | [127] | |

| B. brongniartii | Solovakian crop fields, hedgerows, and forests | n/a | GM | [88] |

| Fields in east, north, central, and southwest Switzerland | Appendix A, Medium 15 | GM | [61,62] | |

| B. pseudobassiana | Tejocote orchard soils, Mexico | n/a | GM | [86] |

| Solovakian crop fields, meadows, hedgerows, and forests | n/a | GM | [88] | |

| Hedgerows around an organic farming field, Bakkegården, Denmark | n/a | GM | [128] | |

| Soils from grasses, Salix, and Betula community, Greenland | n/a | GM | [107] | |

| Hedgerows in vineyards, Douro wine region, Portugal | n/a | GM | [7] | |

| Vineyards in the states of New South Wales and Victoria, Australia | n/a | TM | [127] | |

| B. australis | Vineyards in the states of New South Wales and Victoria, Australia | Appendix A, Medium 9 (supplemented with 0.2 g/L dodine, 0.1 g/L chloramphenicol, and 0.05 g/L streptomycin sulphate); Appendix A, Medium 15 | TM | [127] |

| B. varroae | Hedgerows in vineyards, Douro wine region, Portugal | n/a | GM | [7] |

| Clonostachys rosea f. rosea | Vineyard soils and hedgerows, Douro wine region, Portugal | n/a | GM; TM | [7] |

| Conidiobolus coronatus | Organically managed farm in Bakkegården, Denmark | n/a | GM | [80] |

| Three conventional citrus farms and three organic citrus farms in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa | n/a | C. capitata | [109] | |

| Cordyceps farinosa | Organically managed farm; Hedgerows with hawthorn, poplar, nettles in Bakkegården, Denmark | n/a | GM | [80] |

| Agricultural habitat and natural habitat, Southern Ontario and the Kawartha Lakes region, Canada | n/a | GM | [76] | |

| Crop fields, meadows, hedgerows, and forests, Slovakia | n/a | GM | [97] | |

| Darmstadt surroundings, Germany | n/a | GM | [73] | |

| Natural and cultivated soils, Finland | n/a | A. aedilis; T. castaneum; TM | [104] | |

| Natural soils, Finland | n/a | GM | [104] | |

| Native woodland soils, Iceland | n/a | GM; TM | [106] | |

| Field crop and hedgerows, Årslev, Denmark | n/a | GM | [126] | |

| Soils from grasses and Salix community, Greenland | n/a | GM | [107] | |

| C. fumosorosea | Organically managed farm and Hedgerows with hawthorn, poplar, nettles in Bakkegården, Denmark | n/a | GM | [80] |

| Agricultural habitat and natural habitat, Southern Ontario and the Kawartha Lakes region, Canada | n/a | GM | [76] | |

| Crop fields, meadows, hedgerows, and forests, Slovakia | Appendix A, Medium 15 | GM | [97] | |

| Darmstadt surroundings, Germany | n/a | GM | [73] | |

| Fields in east, north, central and south west of Switzerland | Appendix A, Medium 15 | GM | [61] | |

| Cultivated soils, Finland | n/a | A. aedilis; T. castaneum | [104] | |

| Natural and cultivated soils, Finland | n/a | TM | [104] | |

| Natural soils, Finland | n/a | GM | [104] | |

| Hedgerows, Årslev, Denmark | n/a | GM | [126] | |

| Soils from Dyras, Salix, and Vaccinium plant communities, Greenland | n/a | GM | [107] | |

| Lecanicillium spp. | Organically managed farm in Bakkegården, Denmark | n/a | GM | [80] |

| Three conventional citrus farms and three organic citrus farms in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa | n/a | C. capitata | [109] | |

| Vineyard soils, Douro wine region, Portugal | n/a | GM; TM | [7] | |

| Metarhizium anisopliae sensu lato and/or M. robertsii | Organically managed farm in Bakkegården, Denmark | n/a | GM | [80] |

| Conventional and organic corn field and soybean field; and field margins with grass strips, Iowa, USA | Appendix A, Medium 14 (supplemented with 0.39 gL−1 dodine and 0.25 gL−1) | GM | [57] | |

| Agricultural habitat and natural habitat, Southern Ontario and the Kawartha Lakes region, Canada | n/a | GM | [76] | |

| Three conventional citrus farms and three organic citrus farms in the Eastern Cape province, South Africa | n/a | T. leucotreta; GM | [109] | |

| Cornfields, Iowa, USA | n/a | D. virgifera virgifera; TM; GM | [110] | |

| Tejocote orchard soils, Mexico | n/a | GM | [86] | |

| Crop fields, meadows, hedgerows, and forests, Slovakia | Appendix A, Medium 15 | GM | [97] | |

| Darmstadt surroundings, Germany | n/a | GM | [73] | |

| Fields in east, north, central, and southwest Switzerland | Appendix A, Medium 15 | GM | [61] | |

| Argan forests, Morocco | Appendix A, Medium 15 | GM | [95] | |

| Cultivated soils, Finland | n/a | A. aedilis; T. castaneum | [104] | |

| Natural and cultivated soils, Finland | n/a | GM; TM | [104] | |

| Native woodland soils, Iceland | n/a | TM | [106] | |

| Field crop and hedgerows, Årslev, Denmark | n/a | GM | [126] | |

| Soils near ant nests, Tropical forest, Panama | Appendix A, Medium 9 (with and without supplementation of 0.01% (v/v) dodine, 0.01% (v/v) streptomycinsulphate, and 0.005% (v/v) chloramphenicol) | GM; TM | [105] | |

| Soils from grass, sugarcane and lime grass, Acatlán de Pérez Figueroa, Oaxaca, Mexico | Appendix A, Medium 12, Medium 13 | GM | [100] | |

| Field crop and hedgerows, Årslev, Denmark | n/a | TM | [93] | |

| Vineyard soils, Douro wine region, Portugal | n/a | GM; TM | [7] | |

| Vineyards in the states of New South Wales and Victoria, Australia | Appendix A, Medium 9, (supplemented with 0.2 g/L dodine, 0.1 g/L chloramphenicol, and 0.05 g/L streptomycin sulphate); Appendix A, Medium 15 | TM | [127] | |

| Corn, soybean and alfalfa field with different farming treatments (chisel-till, no-till, organic 6-year rotation) in Prince George’s County, Maryland, USA | Appendix A, Medium 10 (with varying strength of CTAB); Appendix A, Medium 15 (with varying strength of dodine) | n/a | [99] | |

| Cultivated habitats (olive and stone-fruit crops, horticultural crops, cereals crops, leguminous crops, and sunflower); and natural habitats (natural forests, pastures, riverbanks, and desert areas) in Spain and the Canary and the Balearic Archipelagos | n/a | GM | [81] | |

| M. pingshaense | Sugar cane leaf, Acatlán de Pérez Figueroa, Oaxaca, Mexico | Appendix A, Medium 12, Medium 13 | n/a | [100] |

| Vineyards in the states of New South Wales and Victoria, Australia | n/a | TM | [127] | |

| Soybean (no-till), and corn (chisel-till) farming field in Prince George’s County, Maryland, USA | Appendix A, Medium 10 (with varying strength of CTAB); Appendix A, Medium 15 (with varying strength of dodine) | n/a | [99] | |

| M. brunneum | Oilseed rape, Winter wheat and Grass pasture, Eastern Denmark | Appendix A, Medium 13 | TM | [96] |

| Field crop and hedgerows, Årslev, Denmark | n/a | TM | [93] | |

| Vineyards in the states of New South Wales and Victoria, Australia | Appendix A, Medium 9 (supplemented with 0.2 g/L dodine, 0.1 g/L chloramphenicol, and 0.05 g/L streptomycin sulphate); Appendix A, Medium 15 | TM | [127] | |

| Corn (two systems: organic 6 year rotation; and no-till), and soybean (organic 6 year rotation) farming in Prince George’s County, Maryland, USA | Appendix A, Medium 10 (with varying strength of CTAB); Appendix A, Medium 15 (with varying strength of dodine) | n/a | [99] | |

| M. guizhouense | Lime grass soil, Acatlán de Pérez Figueroa, Oaxaca, Mexico | n/a | GM | [100] |

| Vineyard soils, Douro wine region, Portugal | n/a | GM | [7] | |

| Vineyards in the states of New South Wales and Victoria, Australia | n/a | TM | [127] | |

| M. flavoviride | Organically managed farm and Hedgerows with hawthorn, poplar, nettles in Bakkegården, Denmark | n/a | GM | [80] |

| Three conventional citrus farms and three organic citrus farms in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa | n/a | T. leucotreta; GM | [109] | |

| Oilseed rape, Winter wheat and Grass pasture, Eastern Denmark | Appendix A, Medium 13 | TM | [96] | |

| Field crop and hedgerows, Årslev, Denmark | n/a | TM | [93] | |

| Vineyards in the states of New South Wales and Victoria, Australia | Appendix A, Medium 9 (supplemented with 0.2 g/L dodine, 0.1 g/L chloramphenicol, and 0.05 g/L streptomycin sulphate); Appendix A, Medium 15 | TM | [127] | |

| M. majus | Grass pasture, Eastern Denmark | Appendix A, Medium 13 | n/a | [96] |

| Vineyards in the states of New South Wales and Victoria, Australia | Appendix A, Medium 9 (supplemented with 0.2 g/L dodine, 0.1 g/L chloramphenicol, and 0.05 g/L streptomycin sulphate); Appendix A, Medium 15 | n/a | [127] | |

| Purpureocillium lilacinum | Argan forests in Morocco | Appendix A, Medium 15 | GM | [95] |

| Vineyard soils, Douro wine region, Portugal | n/a | GM; TM | [7] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharma, L.; Bohra, N.; Rajput, V.D.; Quiroz-Figueroa, F.R.; Singh, R.K.; Marques, G. Advances in Entomopathogen Isolation: A Case of Bacteria and Fungi. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9010016

Sharma L, Bohra N, Rajput VD, Quiroz-Figueroa FR, Singh RK, Marques G. Advances in Entomopathogen Isolation: A Case of Bacteria and Fungi. Microorganisms. 2021; 9(1):16. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9010016

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharma, Lav, Nitin Bohra, Vishnu D. Rajput, Francisco Roberto Quiroz-Figueroa, Rupesh Kumar Singh, and Guilhermina Marques. 2021. "Advances in Entomopathogen Isolation: A Case of Bacteria and Fungi" Microorganisms 9, no. 1: 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9010016

APA StyleSharma, L., Bohra, N., Rajput, V. D., Quiroz-Figueroa, F. R., Singh, R. K., & Marques, G. (2021). Advances in Entomopathogen Isolation: A Case of Bacteria and Fungi. Microorganisms, 9(1), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9010016