Clinical and Genetic Characteristics of Enterobacter cloacae and Klebsiella aerogenes in Children

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Definitions

2.2. Whole-Genome Sequencing

2.3. Species Identification

2.4. Multilocus Sequence Typing

2.5. Antimicrobial Resistance Gene Detection

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Subject Characteristics

3.2. Clinical and Microbiological Characteristics of ECC and K. aerogenes

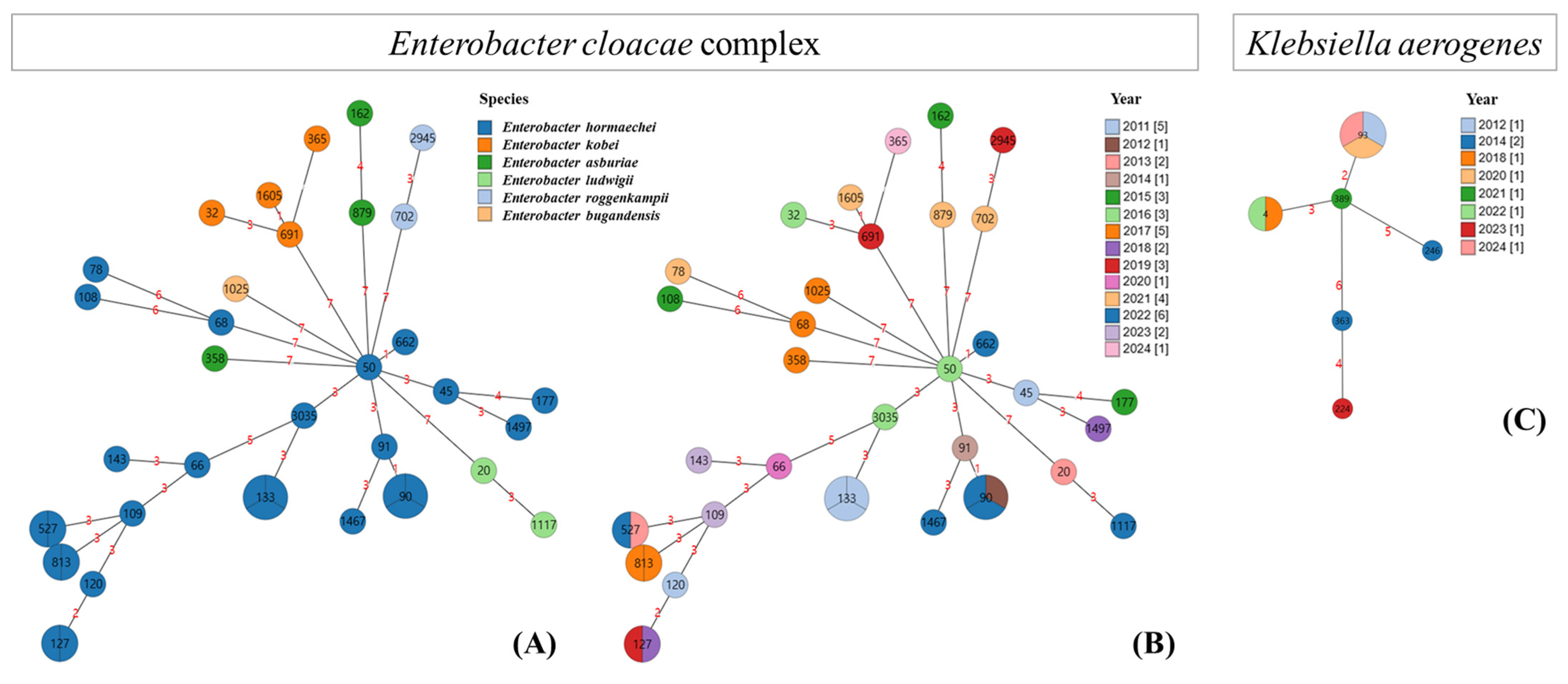

3.3. Species Identification and MLST of the ECC and K. aerogenes

3.4. Phylogenetic Tree of the ECC and K. aerogenes Based on MLST

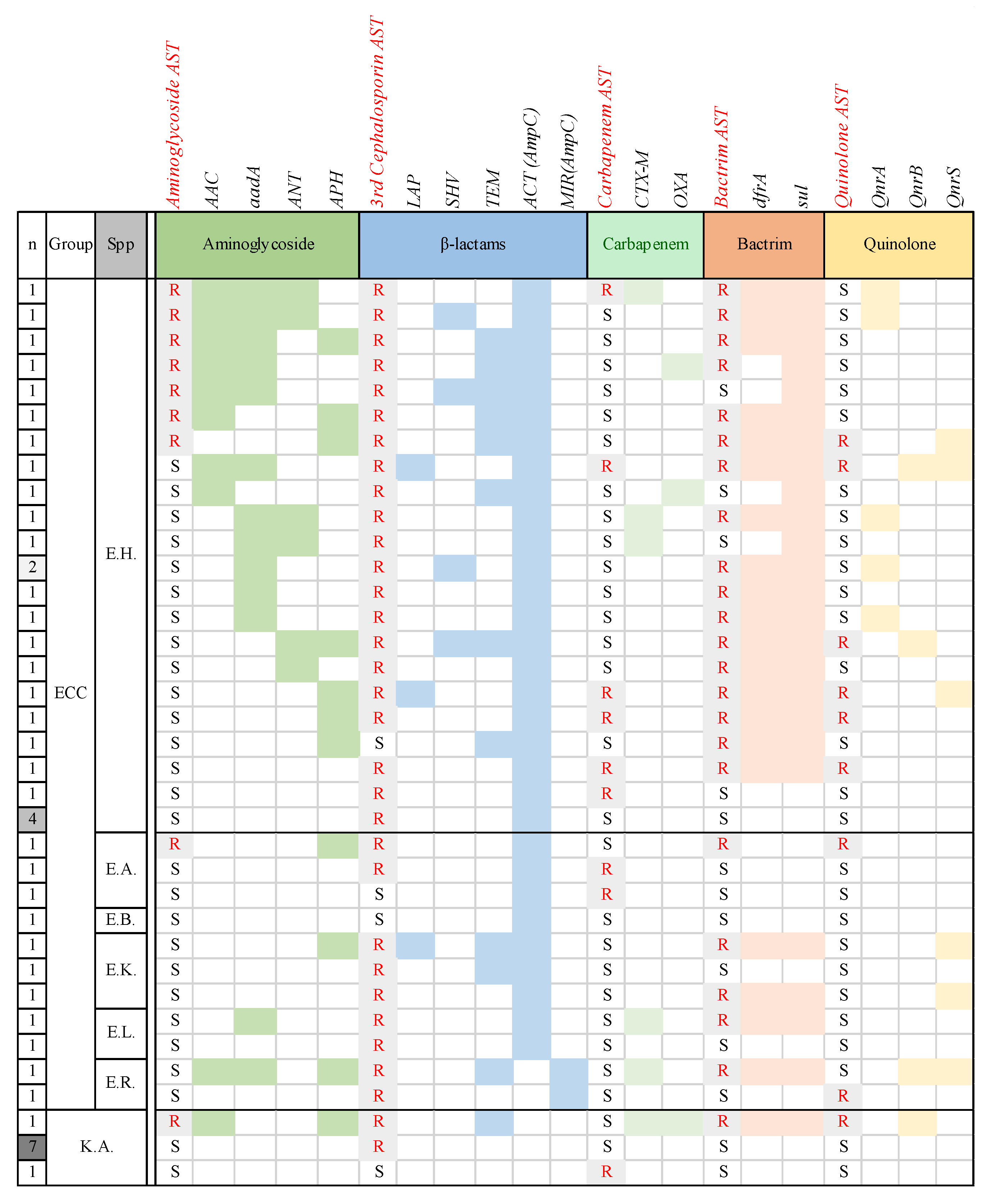

3.5. Antimicrobial Resistance Genes Detected in ECC and K. aerogenes

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GNBs | Gram-negative bacteria |

| ESBL | extended-spectrum β-lactamase |

| CRE | carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae |

| ECC | Enterobacter cloacae complex |

| BSI | bloodstream infection |

| SNUCH | Seoul National University Children’s Hospital |

| CDW | clinical data warehouse |

| AST | antimicrobial susceptibility testing |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| IRB | institutional review board |

| WGS | whole-genome sequencing |

| MLST | multilocus sequence typing |

| ST | sequence type |

| IQR | interquartile range |

| HOD | haemato-oncologic disease |

| CLABSI | central line-associated BSI |

| PIP-TAZ | piperacillin–tazobactam |

| TMP-SMX | trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole |

| OR | odds ratio |

| CI | confidence interval |

References

- Sturenburg, E.; Mack, D. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: Implications for the clinical microbiology laboratory, therapy, and infection control. J. Infect. 2003, 47, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukac, P.J.; Bonomo, R.A.; Logan, L.K. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in children: Old foe, emerging threat. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 60, 1389–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.M.S.; Abidin, A.Z.; Liew, S.M.; Roberts, J.A.; Sime, F.B. The global prevalence of multidrug-resistance among Acinetobacter baumannii causing hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia and its associated mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. 2019, 79, 593–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamma, P.D.; Doi, Y.; Bonomo, R.A.; Johnson, J.K.; Simner, P.J. Antibacterial Resistance Leadership Group. A primer on AmpC beta-lactamases: Necessary knowledge for an increasingly multidrug-resistant world. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 69, 1446–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavda, K.D.; Chen, L.; Fouts, D.E.; Sutton, G.; Brinkac, L.; Jenkins, S.G.; Bonomo, R.A.; Adams, M.D.; Kreiswirth, B.N. Comprehensive genome analysis of carbapenemase-producing Enterobacter spp.: New insights into phylogeny, population structure, and resistance mechanisms. mBio 2016, 7, e02093-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, M.; Huh, K.; Ko, J.H.; Cho, S.Y.; Huh, H.J.; Lee, N.Y.; Kang, C.I.; Chung, D.R.; Peck, K.R. Difference in the clinical outcome of bloodstream infections caused by Klebsiella aerogenes and Enterobacter cloacae complex. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2021, 8, ofab390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, A.; Sucgang, R.; Hamill, R.J.; Zechiedrich, L.; Trautner, B.W. Mortality difference from Klebsiella aerogenes vs Enterobacter cloacae bloodstream infections. Access Microbiol. 2023, 5, acmi000421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laupland, K.B.; Edwards, F.; Harris, P.N.A.; Paterson, D.L. Significant clinical differences but not outcomes between Klebsiella aerogenes and Enterobacter cloacae bloodstream infections: A comparative cohort study. Infection 2023, 51, 1445–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, M.; Gathara, D.; Lopez-Hernandez, I.; Perez-Crespo, P.M.M.; Perez-Rodriguez, M.T.; Sousa, A.; Plata, A.; Reguera-Iglesias, J.M.; Boix-Palop, L.; Dietl, B.; et al. Differences in clinical outcomes of bloodstream infections caused by Klebsiella aerogenes, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterobacter cloacae: A multicentre cohort study. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2024, 23, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 30th ed.; CLSI: Wayne, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, J.W.; Fine, M.J.; Shlaes, D.M.; Quinn, J.P.; Hooper, D.C.; Johnson, M.P.; Ramphal, R.; Wagener, M.M.; Miyashiro, D.K.; Yu, V.L. Enterobacter bacteremia: Clinical features and emergence of antibiotic resistance during therapy. Ann. Intern. Med. 1991, 115, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Lee, J.E.; Park, S.J.; Choi, S.H.; Lee, S.O.; Jeong, J.Y.; Kim, M.N.; Woo, J.H.; Kim, Y.S. Emergence of antibiotic resistance during therapy for infections caused by Enterobacteriaceae producing AmpC beta-lactamase: Implications for antibiotic use. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Marin, R.; Navarro-Amuedo, D.; Gasch-Blasi, O.; Rodriguez-Martinez, J.M.; Calvo-Montes, J.; Lara-Contreras, R.; Lepe-Jimenez, J.A.; Tubau-Quintano, F.; Cano-Garcia, M.E.; Rodriguez-Lopez, F.; et al. A prospective, multicenter case control study of risk factors for acquisition and mortality in Enterobacter species bacteremia. J. Infect. 2020, 80, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, H.; Hong, J.Y.; Byeon, J.H.; Kim, Y.K.; Lee, H.J. High prevalence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing strains among blood isolates of Enterobacter spp. collected in a tertiary hospital during an 8-year period and their antimicrobial susceptibility patterns. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 3159–3161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesevich, A.; Sutton, G.; Ruffin, F.; Park, L.P.; Fouts, D.E.; Fowler, V.G., Jr.; Thaden, J.T. Newly named Klebsiella aerogenes (formerly Enterobacter aerogenes) is associated with poor clinical outcomes relative to other Enterobacter species in patients with bloodstream infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2020, 58, e00582-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, E.H.; Park, K.H.; Jang, E.Y.; Lee, E.J.; Chong, Y.P.; Cho, O.H.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.O.; Sung, H.; Kim, M.N.; et al. Comparison of the clinical and microbiologic characteristics of patients with Enterobacter cloacae and Enterobacter aerogenes bacteremia: A prospective observation study. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2010, 66, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Marin, R.; Lepe, J.A.; Gasch-Blasi, O.; Rodriguez-Martinez, J.M.; Calvo-Montes, J.; Lara-Contreras, R.; Martin-Gandul, C.; Tubau-Quintano, F.; Cano-Garcia, M.E.; Rodriguez-Lopez, F.; et al. Clinical characteristics and outcome of bacteraemia caused by Enterobacter cloacae and Klebsiella aerogenes: More similarities than differences. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 25, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Wei, L.; Feng, Y.; Xie, Y.; Zong, Z. Precise species identification by whole-genome sequencing of Enterobacter bloodstream infection, China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2021, 27, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarangi, J.; Matsuo, N.; Nonogaki, R.; Hayashi, M.; Kawamura, K.; Suzuki, M.; Jin, W.; Tamai, K.; Ogawa, M.; Wachino, J.I.; et al. Molecular epidemiology of Enterobacter cloacae Complex isolates with reduced carbapenem susceptibility recovered by blood culture. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emeraud, C.; Petit, C.; Gauthier, L.; Bonnin, R.A.; Naas, T.; Dortet, L. Emergence of VIM-producing Enterobacter cloacae complex in France between 2015 and 2018. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 77, 944–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.; Zhu, M.; Li, Y.; Huang, D.; Wang, L.; Yan, C.; Zhang, L.; Dong, F.; Lu, J.; Lin, X.; et al. Whole-genome sequencing-based species classification, multilocus sequence typing, and antimicrobial resistance mechanism analysis of the Enterobacter cloacae complex in southern China. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0216022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izdebski, R.; Baraniak, A.; Herda, M.; Fiett, J.; Bonten, M.J.; Carmeli, Y.; Goossens, H.; Hryniewicz, W.; Brun-Buisson, C.; Gniadkowski, M.; et al. MLST reveals potentially high-risk international clones of Enterobacter cloacae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davin-Regli, A.; Pages, J.M. Enterobacter aerogenes and Enterobacter cloacae; versatile bacterial pathogens confronting antibiotic treatment. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livermore, D.M.; Brown, D.F. Detection of beta-lactamase-mediated resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2001, 48, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maillard, A.; Dortet, L.; Delory, T.; Lafaurie, M.; Bleibtreu, A.; Treatment of AmpC Producing Enterobacterales Study Group. Mutation rate of AmpC beta-lactamase-producing enterobacterales and treatment in clinical practice: A word of caution. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, 79, 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. of Cases (%) | p-Value * | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | ECC | K. aerogenes | ||

| (n = 115) | (n = 86) | (n = 29) | ||

| Sex, male | 54 (47.0) | 43 (50.0) | 11 (37.9) | 0.286 |

| Median age (IQR), years | 4.3 (0.3–11.9) | 7.8 (1.2–13.0) | 0.3 (0.1–4.3) | 0.001 |

| Underlying disease | ||||

| Haemato-oncologic | 58 (50.4) | 52 (60.5) | 6 (20.7) | <0.001 |

| Preterm (GA < 34 weeks) | 18 (15.7) | 10 (11.6) | 8 (27.6) | 0.031 |

| Gastrointestinal/hepatobiliary | 18 (15.7) | 14 (16.3) | 4 (13.8) | 1.000 |

| Congenital heart disease | 15 (13.0) | 9 (10.5) | 6 (20.7) | 0.121 |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Urosepsis | 8 (7.0) | 3 (3.5) | 5 (17.2) | 0.027 |

| CLABSI | 67 (58.3) | 52 (60.5) | 15 (51.7) | 0.360 |

| Empirical antibiotics | ||||

| 3rd-generation cephalosporin | 7 (6.1) | 2 (2.3) | 5 (17.2) | 0.012 |

| Piperacillin–tazobactam | 17 (14.8) | 13 (15.1) | 4 (13.8) | 1.000 |

| Cefepime | 3 (2.6) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (6.9) | 0.164 |

| Meropenem | 88 (76.5) | 70 (81.4) | 18 (62.1) | 0.029 |

| Antimicrobial susceptibility to | ||||

| empirical antibiotics used | 107 (93.0) | 80 (93.0) | 27 (93.1) | 1.000 |

| Outcome | ||||

| Cure | 104 (90.4) | 79 (91.9) | 25 (86.2) | 0.471 |

| Recurrence | 6 (5.2) | 5 (5.8) | 1 (3.4) | 1.000 |

| Mortality, total in hospital | 19 (16.5) | 11 (12.8) | 8 (27.6) | 0.077 |

| attributable | 9 (7.8) | 5 (5.8) | 4 (13.8) | 0.234 |

| all-cause 30 d | 11 (9.6) | 5 (5.8) | 6 (20.7) | 0.022 |

| all-cause 100 d | 18 (15.7) | 10 (11.6) | 8 (27.6) | 0.050 |

| Target Antibiotics and AMR Genes | E. hormaechei (n = 26) | Other ECC Strains (n = 11) | K. aerogenes (n = 9) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aminoglycoside | |||

| AAC | 8 (30.8) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (11.1) |

| aadA | 12 (46.2) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0) |

| ANT | 6 (23.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| APH | 7 (26.9) | 3 (27.3) | 1 (11.1) |

| Beta-lactam | |||

| ACT (ampC) | 26 (100) | 9 (81.8) | 0 (0) |

| MIR (ampC) | 0 (0) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0) |

| CTX-M | 5 (19.2) | 2 (18.2) | 1 (11.1) |

| LAP | 2 (7.7) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0) |

| OXA | 2 (7.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (11.1) |

| SHV | 5 (19.2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| TEM | 8 (30.8) | 3 (27.3) | 1 (11.1) |

| Bactrim | |||

| dfrA | 17 (65.4) | 4 (36.4) | 1 (11.1) |

| sul | 21 (80.8) | 4 (36.4) | 1 (11.1) |

| Quinolone | |||

| Qnr | 10 (38.5) | 3 (27.3) | 1 (11.1) |

| Tetracycline | |||

| tet | 4 (15.4) | 2 (18.2) | 1 (11.1) |

| Colistin | |||

| MCR | 11 (42.3) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0) |

| Antiseptics | |||

| qacE | 17 (65.4) | 3 (27.3) | 0 (0) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yun, K.W.; Kim, Y.E.; Kang, D.; Moon, H.J. Clinical and Genetic Characteristics of Enterobacter cloacae and Klebsiella aerogenes in Children. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 292. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020292

Yun KW, Kim YE, Kang D, Moon HJ. Clinical and Genetic Characteristics of Enterobacter cloacae and Klebsiella aerogenes in Children. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(2):292. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020292

Chicago/Turabian StyleYun, Ki Wook, Ye Eun Kim, Dayun Kang, and Hye Jeong Moon. 2026. "Clinical and Genetic Characteristics of Enterobacter cloacae and Klebsiella aerogenes in Children" Microorganisms 14, no. 2: 292. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020292

APA StyleYun, K. W., Kim, Y. E., Kang, D., & Moon, H. J. (2026). Clinical and Genetic Characteristics of Enterobacter cloacae and Klebsiella aerogenes in Children. Microorganisms, 14(2), 292. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020292