Probiotic and Dietary Supplements Intervention in Age-Related Neurodegenerative Disorders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

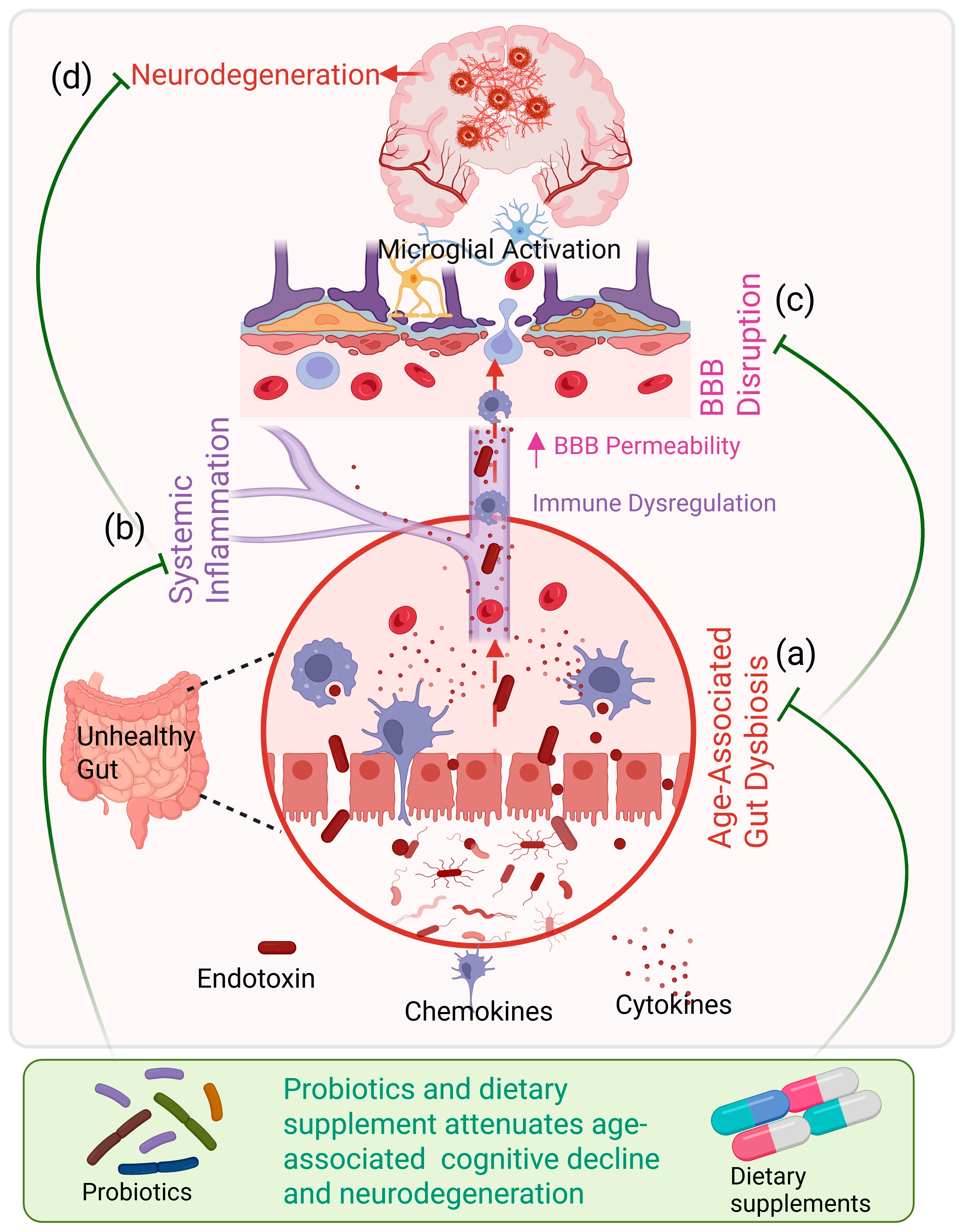

3. Mechanistic Interface: Aging, Gut Dysbiosis, and Neurodegeneration

4. Interventions Based on Different Neurodegenerative Diseases

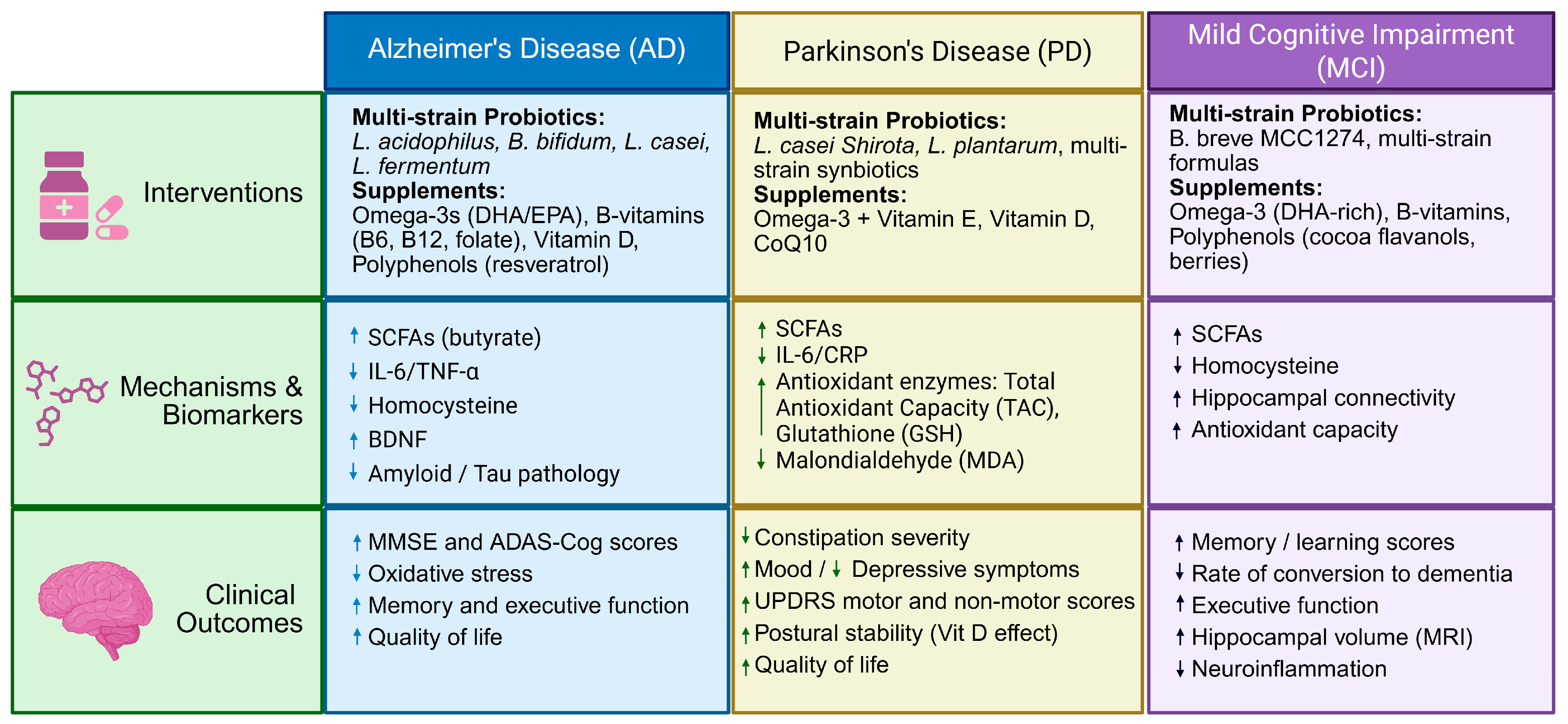

4.1. Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)

4.1.1. Preclinical Evidence

4.1.2. Clinical Evidence

4.2. Parkinson’s Disease (PD)

4.2.1. Preclinical Evidence

4.2.2. Clinical Evidence

4.3. Mild Cognitive Impairment and Age-Related Cognitive Decline (MCI)

4.3.1. Preclinical Evidence

4.3.2. Clinical Evidence

| Author (Year) | Disease/Population | Study Design | N (Number of Participants) | Intervention (Strain/Supplement) | Duration | Primary Outcomes | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akbari et al. (2016) [53] | AD | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 60 | Lactobacillus acidophilus, L. casei, Bifidobacterium bifidum, L. fermentum | 12 weeks | MMSE, metabolic markers | Modest but significant improvement in MMSE; reduced insulin resistance and inflammatory markers |

| Tamtaji et al. (2019) [75] | AD | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 79 | Multi-strain probiotics + selenium | 12 weeks | MMSE, oxidative stress, cytokines | Small improvement in MMSE; reduced IL-6, TNF-α, oxidative stress |

| Xiao et al. (2020) [76] | MCI | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 80 | Bifidobacterium breve MCC1274 | 16 weeks | Cognitive battery, inflammatory markers | Improved memory and visuospatial function; reduced CRP and IL-1β |

| Naomi et al. (2021) [19] | AD & MCI (meta-analysis) | Systematic review & meta-analysis | 22 | Various probiotic formulations | 8–24 weeks | MMSE, ADAS-Cog | Small but consistent cognitive improvements; high heterogeneity |

| Barichella et al. (2016) [82] | PD | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 120 | Multi-strain probiotics + prebiotic fiber (synbiotic) | 4 weeks | Constipation scores, GI outcomes | Significant improvement in bowel function; no disease-modifying effects |

| Yang et al. (2023) [83] | PD | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 56 | Lacticaseibacillus paracasei Shirota | 12 weeks | GI symptoms, microbiome composition | Improved GI symptoms; favorable microbiome shifts |

| Yurko-Mauro et al. (2010) [66] | Age-related cognitive decline | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled | 485 | DHA-rich omega-3 fatty acids | 24 weeks | Memory performance | Modest improvement in memory in early cognitive decline |

| Witte et al. (2014) [58] | Healthy older adults | Randomized, placebo-controlled | 46 | Resveratrol | 26 weeks | Memory, hippocampal connectivity | Improved memory and hippocampal functional connectivity |

| Baker et al. (2023) [97] | Older adults | Randomized, placebo-controlled | >2000 | Multivitamin–mineral supplement | 3 years | Global cognition | Slowed cognitive decline; greater benefit in high-risk individuals |

5. Limitations

6. Challenges and Future Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hou, Y.; Dan, X.; Babbar, M.; Wei, Y.; Hasselbalch, S.G.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloem, B.R.; Okun, M.S.; Klein, C. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 2021, 397, 2284–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, W.; Chen, P.; Cai, H.; Zhang, Q.; Su, Z.; Cheung, T.; Jackson, T.; Sha, S.; Xiang, Y.-T. Worldwide prevalence of mild cognitive impairment among community dwellers aged 50 years and older: A meta-analysis and systematic review of epidemiology studies. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afac173. [Google Scholar]

- Prince, M.; Wimo, A.; Guerchet, M.; Ali, G.-C.; Wu, Y.-T.; Prina, M. The Global Impact of Dementia: An Analysis of Prevalence, Incidence, Cost and Trends; World Alzheimer Report 2015; Alzheimer’s Disease International: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2024, 20, 3708–3821. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, U.C.; Gupta, S.C. Optimizing modifiable and lifestyle-related factors in the prevention of dementia disorders with special reference to Alzheimer, Parkinson and autism diseases. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2020, 16, 900–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharias, H.U.; Kaleta, C.; Cossais, F.; Schaeffer, E.; Berndt, H.; Best, L.; Dost, T.; Glüsing, S.; Groussin, M.; Poyet, M. Microbiome and metabolome insights into the role of the gastrointestinal–brain axis in Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease: Unveiling potential therapeutic targets. Metabolites 2022, 12, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaky, M.Y.; Mohamed, E.E.; Ahmed, O.M. Neurodegenerative disorders: Available therapies and their limitations. In Nanocarriers in Neurodegenerative Disorders; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; pp. 29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson Study Group QE3 Investigators. A randomized clinical trial of high-dosage coenzyme Q10 in early parkinson disease no evidence of benefit. JAMA Neurol. 2014, 75, 543–552.

- Peterson, C.T. Dysfunction of the microbiota-gut-brain axis in neurodegenerative disease: The promise of therapeutic modulation with prebiotics, medicinal herbs, probiotics, and synbiotics. J. Evid. Based Integr. Med. 2020, 25, 2515690X20957225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, Y.-C.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Tsai, S.-Y.; Kuo, Y.-W.; Lin, J.-H.; Ho, H.-H.; Chen, J.-F.; Hsia, K.-C.; Sun, Y. Efficacy of probiotic supplements on brain-derived neurotrophic factor, inflammatory biomarkers, oxidative stress and cognitive function in patients with Alzheimer’s dementia: A 12-week randomized, double-blind active-controlled study. Nutrients 2023, 16, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciulla, M.; Marinelli, L.; Cacciatore, I.; Stefano, A.D. Role of dietary supplements in the management of Parkinson’s disease. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.; Glover, C.; Shuler, M.S.; Dayal, V.; Lithander, F.E. The effect of diet on Parkinson’s disease progression, symptoms and severity: A review of randomised controlled trials. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, S.K.; Wang, S.; Mishra, S.P.; Jain, S.; Yadav, H. Protection of Alzheimer’s disease progression by a human-origin probiotics cocktail. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1589. [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi, C.; Garagnani, P.; Parini, P.; Giuliani, C.; Santoro, A. Inflammaging: A new immune–metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 576–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V.; Yadav, D.; Solanki, K.S.; Koul, B.; Song, M. A review on the protective effects of probiotics against Alzheimer’s disease. Biology 2023, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, S.K.; Yadav, D.; Katiyar, S.; Jain, S.; Yadav, H. Postbiotics as Mitochondrial Modulators in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Potential. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cryan, J.F.; O’Riordan, K.J.; Cowan, C.S.; Sandhu, K.V.; Bastiaanssen, T.F.; Boehme, M.; Codagnone, M.G.; Cussotto, S.; Fulling, C.; Golubeva, A.V. The microbiota-gut-brain axis. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1877–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naomi, R.; Embong, H.; Othman, F.; Ghazi, H.F.; Maruthey, N.; Bahari, H. Probiotics for Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review. Nutrients 2021, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, S.K.; Jain, S.; Yadav, H. Age-Related Cognitive Decline and Dementia: Interface of Microbiome-Immune-Neuronal Interactions. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2025, 80, glaf038. [Google Scholar]

- Prajapati, S.K.; Shah, R.; Alford, N.; Mishra, S.P.; Jain, S.; Hansen, B.; Sanberg, P.; Molina, A.J.; Yadav, H. The triple alliance: Microbiome, mitochondria, and metabolites in the context of age-related cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2023, 78, 2187–2202. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A.; Madkan, S.; Patil, P. The role of gut microbiota in neurodegenerative diseases: Current insights and therapeutic implications. Cureus 2023, 15, e47861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, S.; Sisodia, S.S.; Vassar, R.J. The gut microbiome in Alzheimer’s disease: What we know and what remains to be explored. Mol. Neurodegener. 2023, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erny, D.; Hrabě de Angelis, A.L.; Jaitin, D.; Wieghofer, P.; Staszewski, O.; David, E.; Keren-Shaul, H.; Mahlakoiv, T.; Jakobshagen, K.; Buch, T. Host microbiota constantly control maturation and function of microglia in the CNS. Nat. Neurosci. 2015, 18, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, K.; Mu, C.-L.; Farzi, A.; Zhu, W.-Y. Tryptophan metabolism: A link between the gut microbiota and brain. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Chen, T.; Ni, C.; Hu, Y.; Nan, Y.; Lin, W.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, F.; Shi, X.; Lin, Z. Indole-3-propionic acid attenuates HI-related blood–brain barrier injury in neonatal rats by modulating the PXR signaling pathway. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2022, 13, 2897–2912. [Google Scholar]

- Naureen, Z.; Dhuli, K.; Medori, M.C.; Caruso, P.; Manganotti, P.; Chiurazzi, P.; Bertelli, M. Dietary supplements in neurological diseases and brain aging. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63, E174. [Google Scholar]

- Praticò, A.D. Therapeutic opportunities for food supplements in neurodegenerative diseases. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medeiros, D.; McMurry, K.; Pfeiffer, M.; Newsome, K.; Testerman, T.; Graf, J.; Silver, A.C.; Sacchetti, P. Slowing Alzheimer’s disease progression through probiotic supplementation. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1309075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharjee, P.; Singh, V.V.; Prasad, S.K.; Thakur, P.; Acharjee, A. Signaling Pathways and Gut–Brain Axis: Relationship in Neurological Disorders. In Biotics and the Gut–Brain Axis in Neurological Disorders; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 218–233. [Google Scholar]

- Koumpouli, D.; Koumpouli, V.; Koutelidakis, A.E. The Gut–Brain Axis and Neurodegenerative Diseases: The Role of Nutritional Interventions Targeting the Gut Microbiome—A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 5558. [Google Scholar]

- Bonaz, B.; Bazin, T.; Pellissier, S. The vagus nerve at the interface of the microbiota-gut-brain axis. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 336468. [Google Scholar]

- Romano, S.; Savva, G.M.; Bedarf, J.R.; Charles, I.G.; Hildebrand, F.; Narbad, A. Meta-analysis of the Parkinson’s disease gut microbiome suggests alterations linked to intestinal inflammation. NPJ Park. Dis. 2021, 7, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, G. A more holistic perspective of Alzheimer’s disease: Roles of gut microbiome, adipocytes, HPA axis, melatonergic pathway and astrocyte mitochondria in the emergence of autoimmunity. Front. Biosci.-Landmark 2023, 28, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.A.; Rinaman, L.; Cryan, J.F. Stress & the gut-brain axis: Regulation by the microbiome. Neurobiol. Stress 2017, 7, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colca, J.R.; Finck, B.N. Metabolic Mechanisms connecting Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases: Potential avenues for novel therapeutic approaches. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 929328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bou Zerdan, M.; Hebbo, E.; Hijazi, A.; El Gemayel, M.; Nasr, J.; Nasr, D.; Yaghi, M.; Bouferraa, Y.; Nagarajan, A. The gut microbiome and alzheimer’s disease: A growing relationship. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2022, 19, 808–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, P.; Kumar, S.; Chellammal, H.S.J.; Sahu, N.; Srivastava, S.; Kumar, R.; Gasmi, A. Gut Microbiota and Dietary Strategies for Age-Related Diseases. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2025, 69, e70308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saji, N.; Niida, S.; Murotani, K.; Hisada, T.; Tsuduki, T.; Sugimoto, T.; Kimura, A.; Toba, K.; Sakurai, T. Analysis of the relationship between the gut microbiome and dementia: A cross-sectional study conducted in Japan. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Z.-Q.; Shen, L.-L.; Li, W.-W.; Fu, X.; Zeng, F.; Gui, L.; Lü, Y.; Cai, M.; Zhu, C.; Tan, Y.-L. Gut microbiota is altered in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018, 63, 1337–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binda, S.; Hill, C.; Johansen, E.; Obis, D.; Pot, B.; Sanders, M.E.; Tremblay, A.; Ouwehand, A.C. Criteria to qualify microorganisms as “probiotic” in foods and dietary supplements. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-F.; Hsia, K.-C.; Kuo, Y.-W.; Chen, S.-H.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Li, C.-M.; Hsu, Y.-C.; Tsai, S.-Y.; Ho, H.-H. Safety Assessment and Probiotic Potential Comparison of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. infantis BLI-02, Lactobacillus plantarum LPL28, Lactobacillus acidophilus TYCA06, and Lactobacillus paracasei ET-66. Nutrients 2023, 16, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Mal, G.; Kalra, R.S.; Marotta, F. Designer Probiotics and Postbiotics. In Probiotics as Live Biotherapeutics for Veterinary and Human Health, Volume 2: Functional Foods and Post-Genomics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 539–568. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoog, S.; Taneri, P.E.; Roa Díaz, Z.M.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Troup, J.P.; Bally, L.; Franco, O.H.; Glisic, M.; Muka, T. Dietary factors and modulation of bacteria strains of Akkermansia muciniphila and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii: A systematic review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfili, L.; Cecarini, V.; Berardi, S.; Scarpona, S.; Suchodolski, J.S.; Nasuti, C.; Fiorini, D.; Boarelli, M.C.; Rossi, G.; Eleuteri, A.M. Microbiota modulation counteracts Alzheimer’s disease progression influencing neuronal proteolysis and gut hormones plasma levels. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, C.M.; Omoluabi, T.; Janes, A.M.; Rodgers, E.J.; Torraville, S.E.; Negandhi, B.L.; Nobel, T.E.; Mayengbam, S.; Yuan, Q. Targeting early tau pathology: Probiotic diet enhances cognitive function and reduces inflammation in a preclinical Alzheimer’s model. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2025, 17, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Businaro, R.; Vauzour, D.; Sarris, J.; Münch, G.; Gyengesi, E.; Brogelli, L.; Zuzarte, P. Therapeutic opportunities for food supplements in neurodegenerative disease and depression. Front. Nutr. 2021, 8, 669846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chyan, Y.-J.; Poeggeler, B.; Omar, R.A.; Chain, D.G.; Frangione, B.; Ghiso, J.; Pappolla, M.A. Potent neuroprotective properties against the Alzheimer β-amyloid by an endogenous melatonin-related indole structure, indole-3-propionic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 21937–21942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathyasaikumar, K.V.; Blanco-Ayala, T.; Zheng, Y.; Schwieler, L.; Erhardt, S.; Tufvesson-Alm, M.; Poeggeler, B.; Schwarcz, R. The tryptophan metabolite indole-3-propionic acid raises kynurenic acid levels in the rat brain in vivo. Int. J. Tryptophan Res. 2024, 17, 11786469241262876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arpaia, N.; Campbell, C.; Fan, X.; Dikiy, S.; Van Der Veeken, J.; Deroos, P.; Liu, H.; Cross, J.R.; Pfeffer, K.; Coffer, P.J. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature 2013, 504, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furusawa, Y.; Obata, Y.; Fukuda, S.; Endo, T.A.; Nakato, G.; Takahashi, D.; Nakanishi, Y.; Uetake, C.; Kato, K.; Kato, T. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature 2013, 504, 446–450, Erratum in Nature 2014, 506, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.; Kim, M.; Kang, S.G.; Jannasch, A.H.; Cooper, B.; Patterson, J.; Kim, C.H. Short-chain fatty acids induce both effector and regulatory T cells by suppression of histone deacetylases and regulation of the mTOR–S6K pathway. Mucosal Immunol. 2015, 8, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, E.; Asemi, Z.; Daneshvar Kakhaki, R.; Bahmani, F.; Kouchaki, E.; Tamtaji, O.R.; Hamidi, G.A.; Salami, M. Effect of probiotic supplementation on cognitive function and metabolic status in Alzheimer’s disease: A randomized, double-blind and controlled trial. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2016, 8, 229544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vauzour, D.; Camprubi-Robles, M.; Miquel-Kergoat, S.; Andres-Lacueva, C.; Bánáti, D.; Barberger-Gateau, P.; Bowman, G.L.; Caberlotto, L.; Clarke, R.; Hogervorst, E. Nutrition for the ageing brain: Towards evidence for an optimal diet. Ageing Res. Rev. 2017, 35, 222–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheltens, P.; Twisk, J.W.; Blesa, R.; Scarpini, E.; Von Arnim, C.A.; Bongers, A.; Harrison, J.; Swinkels, S.H.; Stam, C.J.; De Waal, H. Efficacy of Souvenaid in mild Alzheimer’s disease: Results from a randomized, controlled trial. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2012, 31, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.D.; Refsum, H. Homocysteine, B vitamins, and cognitive impairment. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2016, 36, 211–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidd, P.M. Omega-3 DHA and EPA for cognition, behavior, and mood: Clinical findings and structural-functional synergies with cell membrane phospholipids. Altern. Med. Rev. 2007, 12, 207. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Witte, A.V.; Kerti, L.; Margulies, D.S.; Flöel, A. Effects of resveratrol on memory performance, hippocampal functional connectivity, and glucose metabolism in healthy older adults. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 7862–7870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankers, W.; Colin, E.M.; Van Hamburg, J.P.; Lubberts, E. Vitamin D in autoimmunity: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Front. Immunol. 2017, 7, 236441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dankers, W.; Davelaar, N.; Van Hamburg, J.P.; Van De Peppel, J.; Colin, E.M.; Lubberts, E. Human memory Th17 cell populations change into anti-inflammatory cells with regulatory capacity upon exposure to active vitamin D. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdaca, G.; Tonacci, A.; Negrini, S.; Greco, M.; Borro, M.; Puppo, F.; Gangemi, S. Emerging role of vitamin D in autoimmune diseases: An update on evidence and therapeutic implications. Autoimmun. Rev. 2019, 18, 102350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, N.; Serhan, C.N. Specialized pro-resolving mediator network: An update on production and actions. Essays Biochem. 2020, 64, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serhan, C.N.; Levy, B.D. Resolvins in inflammation: Emergence of the pro-resolving superfamily of mediators. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 2657–2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, P.C. Marine omega-3 fatty acids and inflammatory processes: Effects, mechanisms and clinical relevance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2015, 1851, 469–484. [Google Scholar]

- Rangel-Huerta, O.D.; Gil, A. Effect of omega-3 fatty acids on cognition: An updated systematic review of randomized clinical trials. Nutr. Rev. 2018, 76, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Yurko-Mauro, K.; McCarthy, D.; Rom, D.; Nelson, E.B.; Ryan, A.S.; Blackwell, A.; Salem, N., Jr.; Stedman, M.; Investigators, M. Beneficial effects of docosahexaenoic acid on cognition in age-related cognitive decline. Alzheimers Dement. 2010, 6, 456–464. [Google Scholar]

- Heneka, M.T.; Carson, M.J.; El Khoury, J.; Landreth, G.E.; Brosseron, F.; Feinstein, D.L.; Jacobs, A.H.; Wyss-Coray, T.; Vitorica, J.; Ransohoff, R.M. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 388–405. [Google Scholar]

- Prajapati, S.K.; Pathak, A.; Samaiya, P.K. Alzheimer’s disease: From early pathogenesis to novel therapeutic approaches. Metab. Brain Dis. 2024, 39, 1231–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlov, S.; Prajapati, S.K.; Yadav, D.; Marcano-Rodriguez, A.; Yadav, H.; Jain, S. Advances in Bioactive Compounds from Plants and Their Applications in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomolecules 2025, 16, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parashar, A.; Mehta, V.; Chauhan, B.; Ghosh, P.; Deb, P.K.; Jaiswal, M.; Prajapati, S.K. Sonic hedgehog signalling pathway contributes in age-related disorders and Alzheimer’s disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 96, 102271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lim, G.P.; Chu, T.; Yang, F.; Beech, W.; Frautschy, S.A.; Cole, G.M. The curry spice curcumin reduces oxidative damage and amyloid pathology in an Alzheimer transgenic mouse. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 8370–8377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Ho, L.; Zhao, Z.; Seror, I.; Humala, N.; Dickstein, D.L.; Thiyagarajan, M.; Percival, S.S.; Talcott, S.T.; Maria Pasinetti, G. Moderate consumption of Cabernet Sauvignon attenuates A neuropathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 2313–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calon, F.; Lim, G.P.; Yang, F.; Morihara, T.; Teter, B.; Ubeda, O.; Rostaing, P.; Triller, A.; Salem, N.; Ashe, K.H. Docosahexaenoic acid protects from dendritic pathology in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Neuron 2004, 43, 633–645. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, A.; Ying, Z.; Gomez-Pinilla, F. Docosahexaenoic acid dietary supplementation enhances the effects of exercise on synaptic plasticity and cognition. Neuroscience 2008, 155, 751–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamtaji, O.R.; Heidari-Soureshjani, R.; Mirhosseini, N.; Kouchaki, E.; Bahmani, F.; Aghadavod, E.; Tajabadi-Ebrahimi, M.; Asemi, Z. Probiotic and selenium co-supplementation, and the effects on clinical, metabolic and genetic status in Alzheimer’s disease: A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 2569–2575. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J.; Katsumata, N.; Bernier, F.; Ohno, K.; Yamauchi, Y.; Odamaki, T.; Yoshikawa, K.; Ito, K.; Kaneko, T. Probiotic Bifidobacterium breve in Improving Cognitive Functions of Older Adults with Suspected Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020, 77, 139–147, Erratum in J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2025, Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1177/13872877251407772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.; Kaushik, M.; Dwivedi, R.; Tiwari, P.; Tripathi, M.; Dada, R. The effect of probiotics on select cognitive domains in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Alzheimers Dis. Rep. 2024, 8, 1422–1433. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, B.; Fu, L.; Yang, Z.; Yu, G. Effect of probiotics on cognitive function and cardiovascular risk factors in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease: An umbrella meta-analysis. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2025, 44, 109. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, S.; Ji, J.-L.; Li, S.; Cao, X.-P.; Xu, W.; Tan, L.; Tan, C.-C. Efficacy and safety of probiotics for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, and Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 730036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhgarjand, C.; Vahabi, Z.; Shab-Bidar, S.; Etesam, F.; Djafarian, K. Effects of probiotic supplements on cognition, anxiety, and physical activity in subjects with mild and moderate Alzheimer’s disease: A randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 1032494. [Google Scholar]

- Prajapati, S.K.; Garabadu, D.; Krishnamurthy, S. Coenzyme Q10 prevents mitochondrial dysfunction and facilitates pharmacological activity of atorvastatin in 6-OHDA induced dopaminergic toxicity in rats. Neurotox. Res. 2017, 31, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barichella, M.; Pacchetti, C.; Bolliri, C.; Cassani, E.; Iorio, L.; Pusani, C.; Pinelli, G.; Privitera, G.; Cesari, I.; Faierman, S.A. Probiotics and prebiotic fiber for constipation associated with Parkinson disease: An RCT. Neurology 2016, 87, 1274–1280. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; He, X.; Xu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Mo, C.; Lai, Y.; Song, Y.; Yan, Z.; Ai, P.; Qian, Y. Effect of Lacticaseibacillus paracasei strain Shirota supplementation on clinical responses and gut microbiome in Parkinson’s disease. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 6828–6839. [Google Scholar]

- Westfall, S.; Lomis, N.; Kahouli, I.; Dia, S.Y.; Singh, S.P.; Prakash, S. Microbiome, probiotics and neurodegenerative diseases: Deciphering the gut brain axis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2017, 74, 3769–3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Prasad, A.A. Probiotics treatment improves hippocampal dependent cognition in a rodent model of Parkinson’s disease. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, T.-H.; Kuo, C.-W.; Hsieh, K.-H.; Shieh, M.-J.; Peng, C.-W.; Chen, Y.-C.; Chang, Y.-L.; Huang, Y.-Z.; Chen, C.-C.; Chang, P.-K. Probiotics alleviate the progressive deterioration of motor functions in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousquet, M.; Saint-Pierre, M.; Julien, C.; Salem, N., Jr.; Cicchetti, F.; Calon, F. Beneficial effects of dietary omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid on toxin-induced neuronal degeneration in an animal model of Parkinson’s disease. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 1213–1225. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.P.; Fletcher-Turner, A.; Yurek, D.M.; Cass, W.A. Calcitriol protection against dopamine loss induced by intracerebroventricular administration of 6-hydroxydopamine. Neurochem. Res. 2006, 31, 533–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cass, W.A.; Peters, L.E.; Fletcher, A.M.; Yurek, D.M. Evoked dopamine overflow is augmented in the striatum of calcitriol treated rats. Neurochem. Int. 2012, 60, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassani, E.; Privitera, G.; Pezzoli, G.; Pusani, C.; Madio, C.; Iorio, L.; Barichella, M. Use of probiotics for the treatment of constipation in Parkinson’s disease patients. Minerva Gastroenterol. Dietol. 2011, 57, 117–121. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, T.M.; Munhoz, R.P.; Alvarez, C.; Naliwaiko, K.; Kiss, Á.; Andreatini, R.; Ferraz, A.C. Depression in Parkinson’s disease: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled pilot study of omega-3 fatty-acid supplementation. J. Affect. Disord. 2008, 111, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taghizadeh, M.; Tamtaji, O.R.; Dadgostar, E.; Kakhaki, R.D.; Bahmani, F.; Abolhassani, J.; Aarabi, M.H.; Kouchaki, E.; Memarzadeh, M.R.; Asemi, Z. The effects of omega-3 fatty acids and vitamin E co-supplementation on clinical and metabolic status in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neurochem. Int. 2017, 108, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, M.; Yoshioka, M.; Hashimoto, M.; Murakami, M.; Noya, M.; Takahashi, D.; Urashima, M. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of vitamin D supplementation in Parkinson disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 1004–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shults, C.W.; Oakes, D.; Kieburtz, K.; Beal, M.F.; Haas, R.; Plumb, S.; Juncos, J.L.; Nutt, J.; Shoulson, I.; Carter, J. Effects of coenzyme Q10 in early Parkinson disease: Evidence of slowing of the functional decline. Arch. Neurol. 2002, 59, 1541–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Huélamo, M.; Rodríguez-Morató, J.; Boronat, A.; De la Torre, R. Modulation of Nrf2 by olive oil and wine polyphenols and neuroprotection. Antioxidants 2017, 6, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.D.; Smith, S.M.; De Jager, C.A.; Whitbread, P.; Johnston, C.; Agacinski, G.; Oulhaj, A.; Bradley, K.M.; Jacoby, R.; Refsum, H. Homocysteine-lowering by B vitamins slows the rate of accelerated brain atrophy in mild cognitive impairment: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e12244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, L.D.; Manson, J.E.; Rapp, S.R.; Sesso, H.D.; Gaussoin, S.A.; Shumaker, S.A.; Espeland, M.A. Effects of cocoa extract and a multivitamin on cognitive function: A randomized clinical trial. Alzheimers Dement. 2023, 19, 1308–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.-S.; Cha, J.; Sim, M.; Jung, S.; Chun, W.Y.; Baik, H.W.; Shin, D.-M. Probiotic supplementation improves cognitive function and mood with changes in gut microbiota in community-dwelling older adults: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2021, 76, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickman, A.M.; Khan, U.A.; Provenzano, F.A.; Yeung, L.-K.; Suzuki, W.; Schroeter, H.; Wall, M.; Sloan, R.P.; Small, S.A. Enhancing dentate gyrus function with dietary flavanols improves cognition in older adults. Nat. Neurosci. 2014, 17, 1798–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soininen, H.; Solomon, A.; Visser, P.J.; Hendrix, S.B.; Blennow, K.; Kivipelto, M.; Hartmann, T.; Hallikainen, I.; Hallikainen, M.; Helisalmi, S. 24-month intervention with a specific multinutrient in people with prodromal Alzheimer’s disease (LipiDiDiet): A randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

D’Anniballe De Salles, C.B.; Prajapati, S.K.; Yadav, D.; Rennar, J.; Marcano-Rodriguez, A.; Yadav, H.; Jain, S. Probiotic and Dietary Supplements Intervention in Age-Related Neurodegenerative Disorders. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020290

D’Anniballe De Salles CB, Prajapati SK, Yadav D, Rennar J, Marcano-Rodriguez A, Yadav H, Jain S. Probiotic and Dietary Supplements Intervention in Age-Related Neurodegenerative Disorders. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(2):290. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020290

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Anniballe De Salles, Carolina Beatrice, Santosh Kumar Prajapati, Dhananjay Yadav, Joell Rennar, Andrea Marcano-Rodriguez, Hariom Yadav, and Shalini Jain. 2026. "Probiotic and Dietary Supplements Intervention in Age-Related Neurodegenerative Disorders" Microorganisms 14, no. 2: 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020290

APA StyleD’Anniballe De Salles, C. B., Prajapati, S. K., Yadav, D., Rennar, J., Marcano-Rodriguez, A., Yadav, H., & Jain, S. (2026). Probiotic and Dietary Supplements Intervention in Age-Related Neurodegenerative Disorders. Microorganisms, 14(2), 290. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14020290