Coupled Effects of Tree Species and Understory Morel on Modulating Soil Microbial Communities and Nutrient Dynamics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Soil Sampling

2.3. Soil Physicochemical Analysis

2.4. The Determination of Soil Enzyme Activities

2.5. High-Throughput Sequencing

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

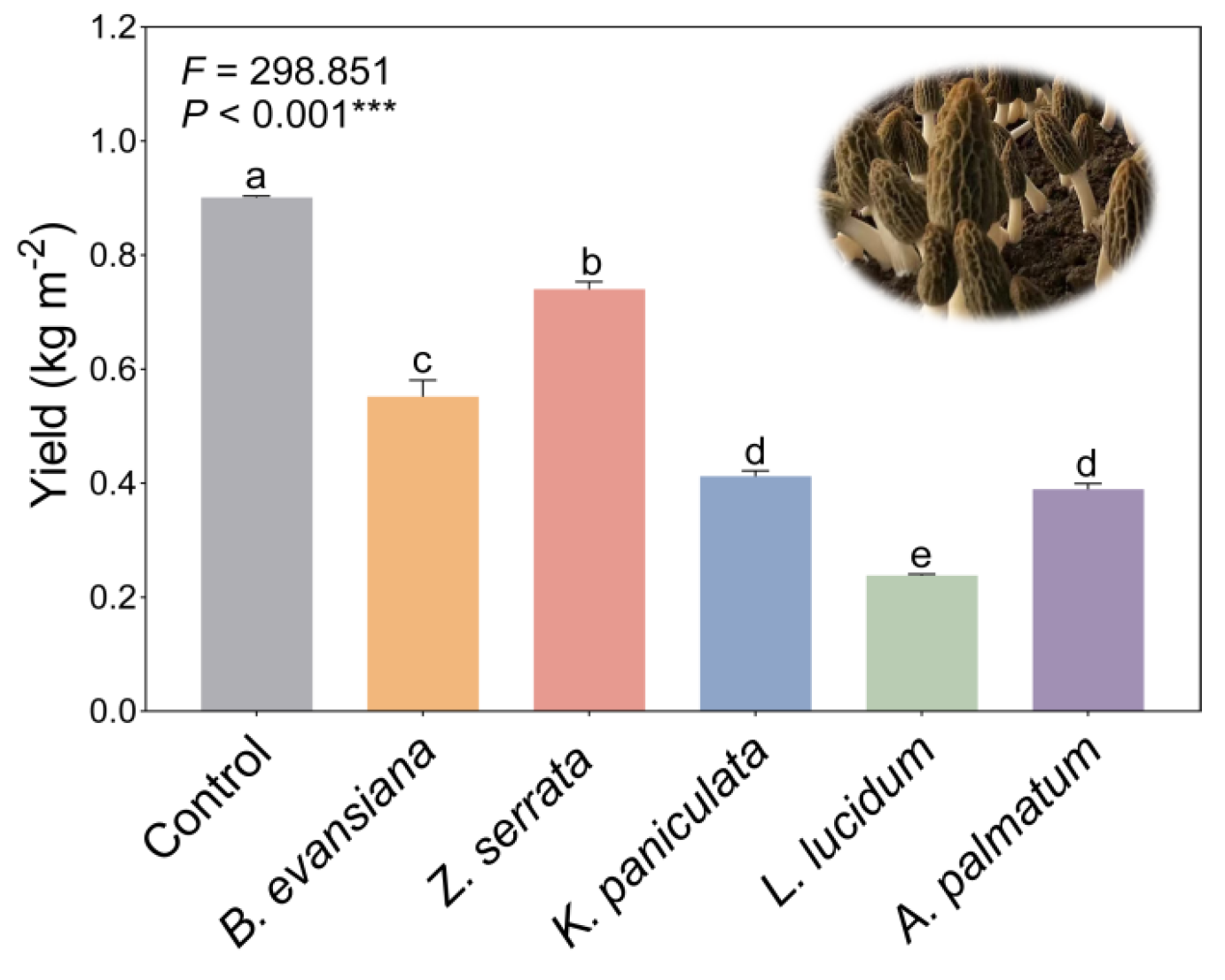

3.1. The Yield of Morels

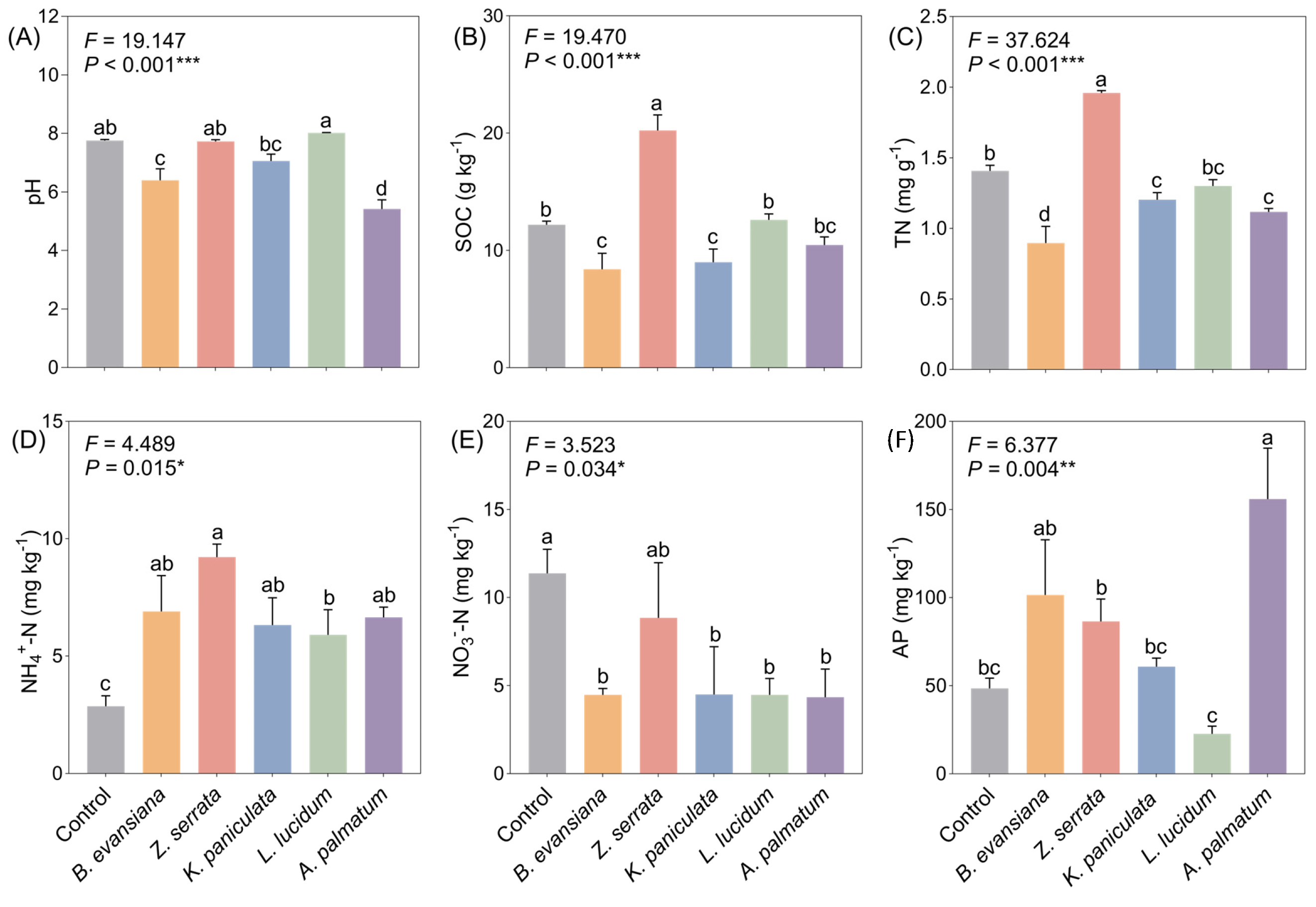

3.2. Physico-Chemical Properties of Soil

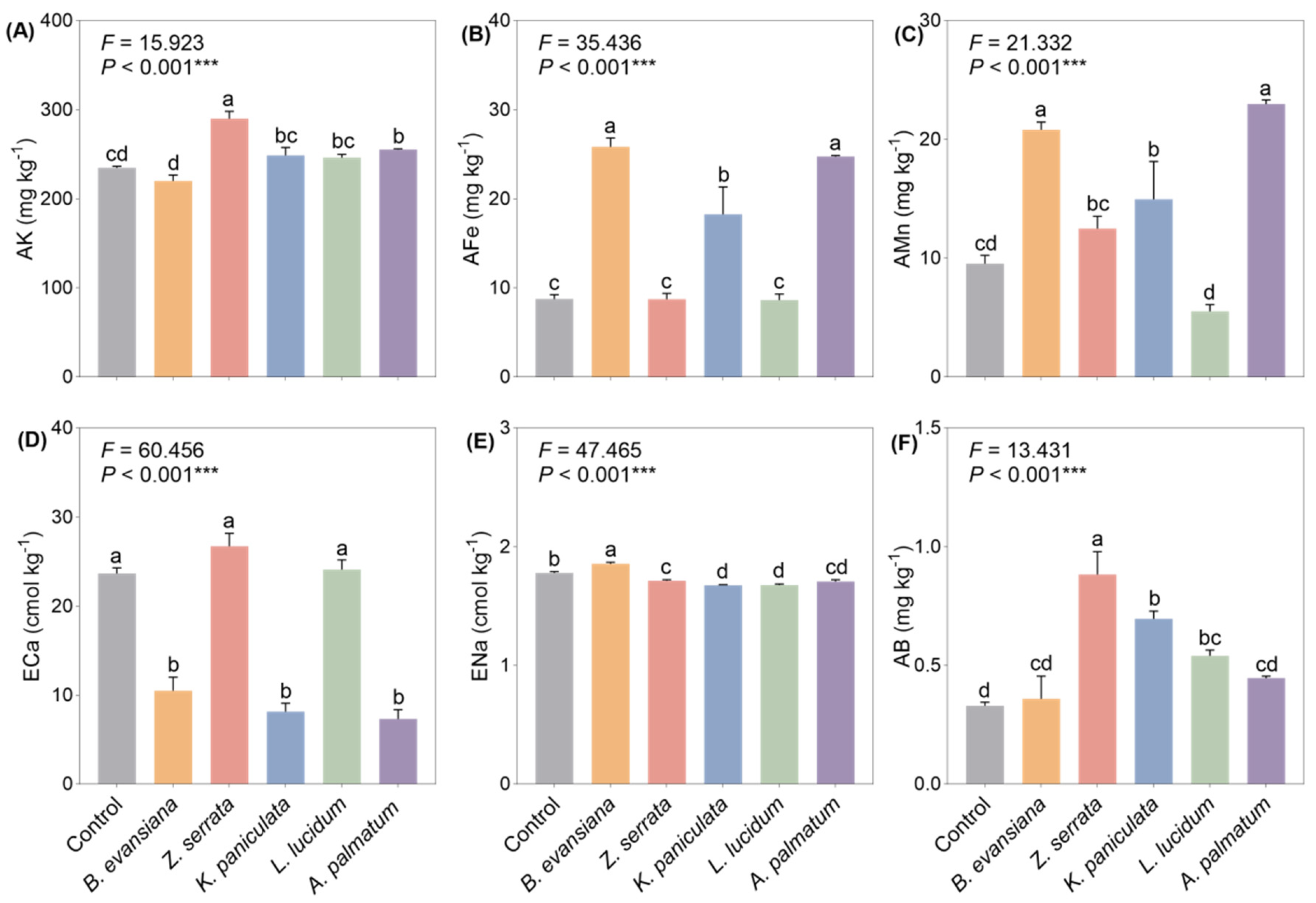

3.3. Soil Mineral Elements

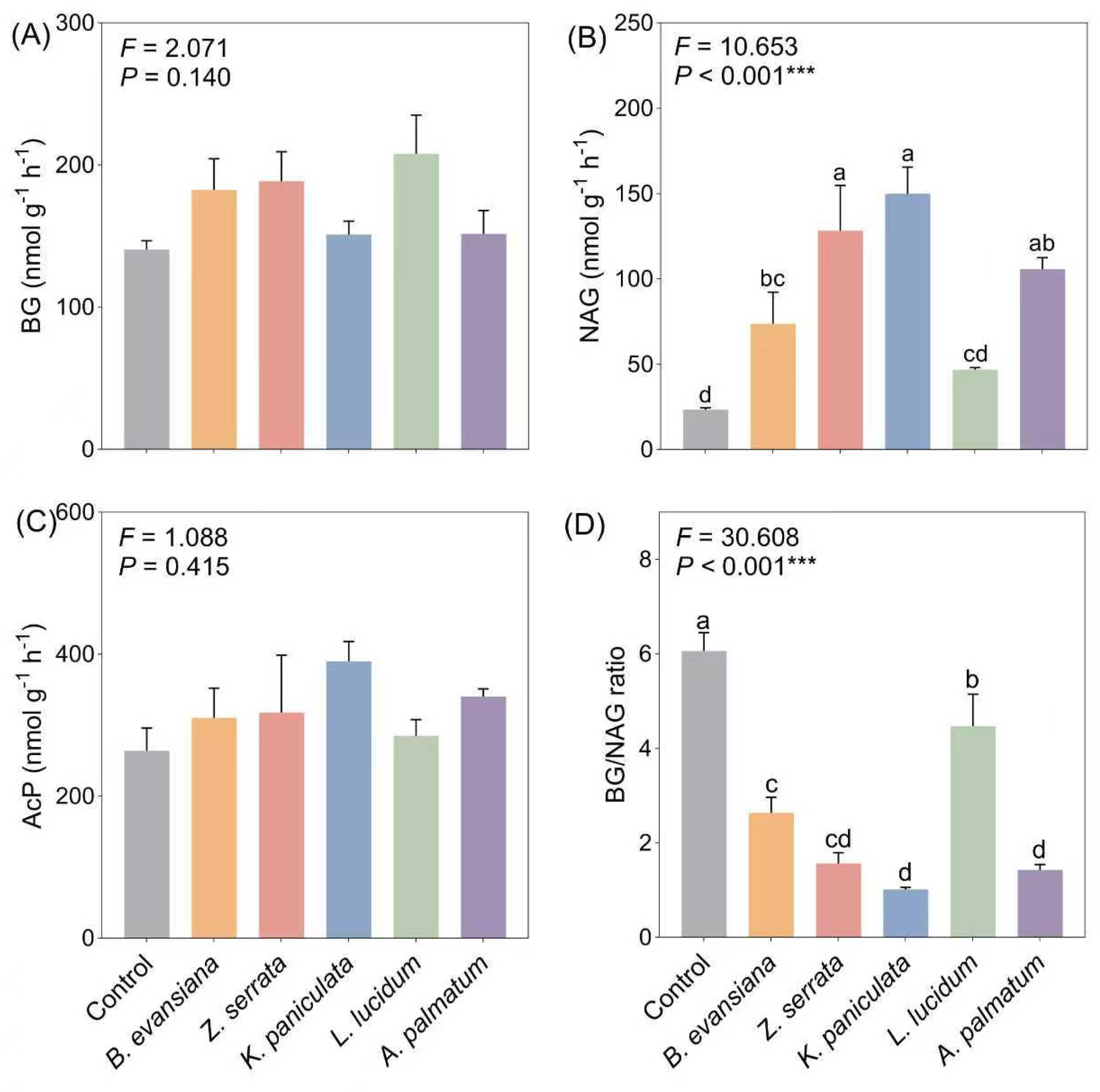

3.4. Soil Enzyme Activities

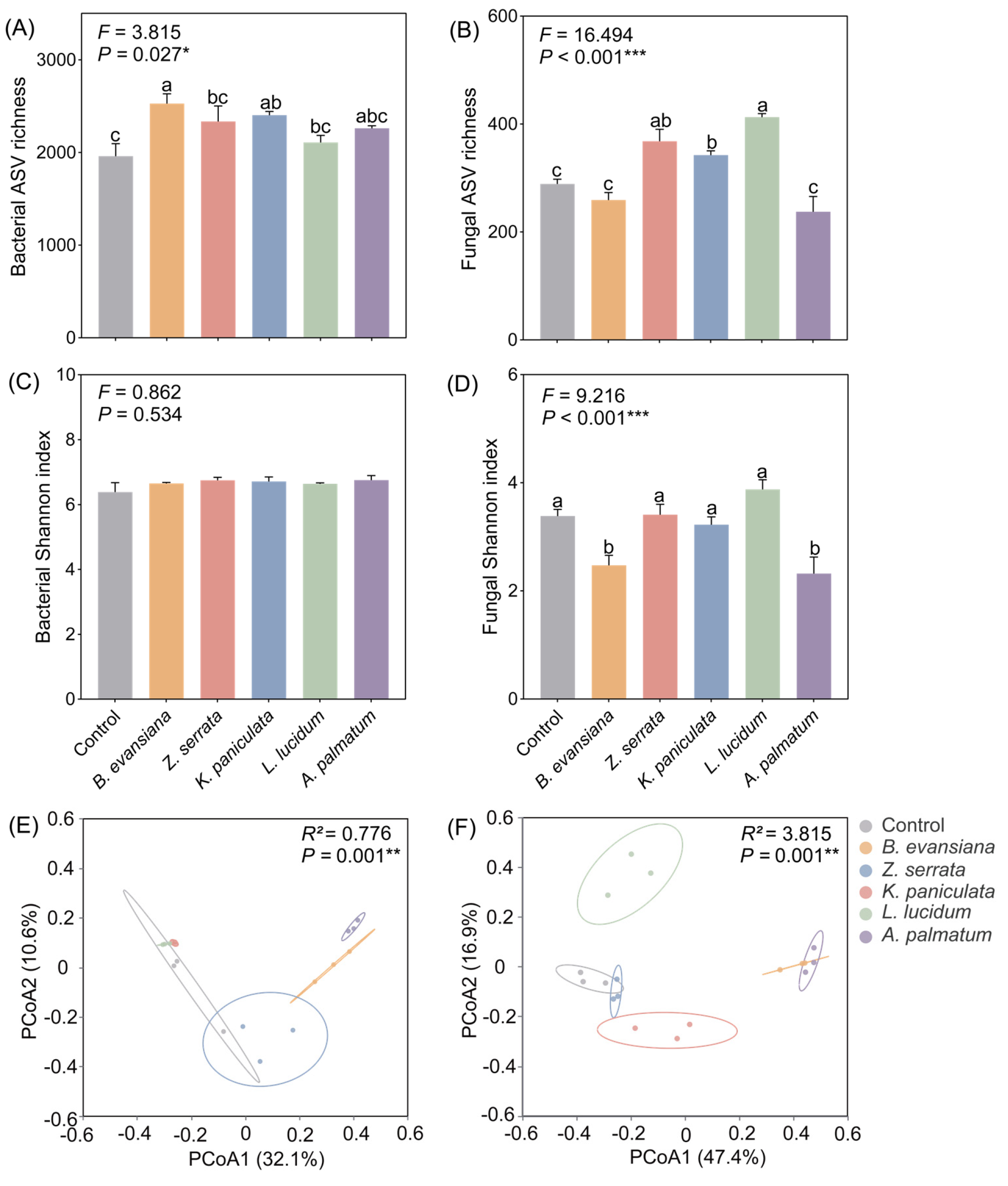

3.5. Soil Microbial Diversity

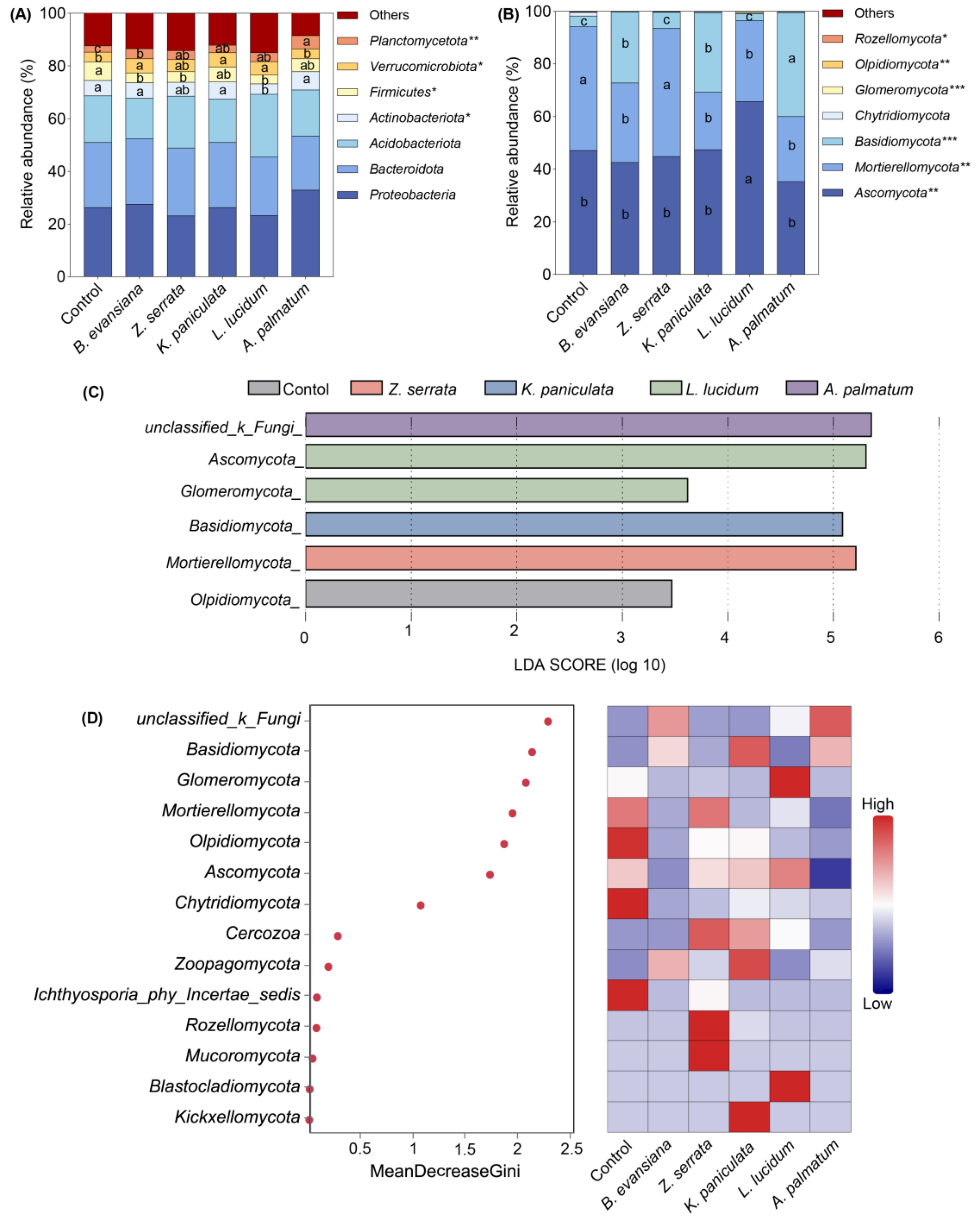

3.6. Soil Microbial Community Composition

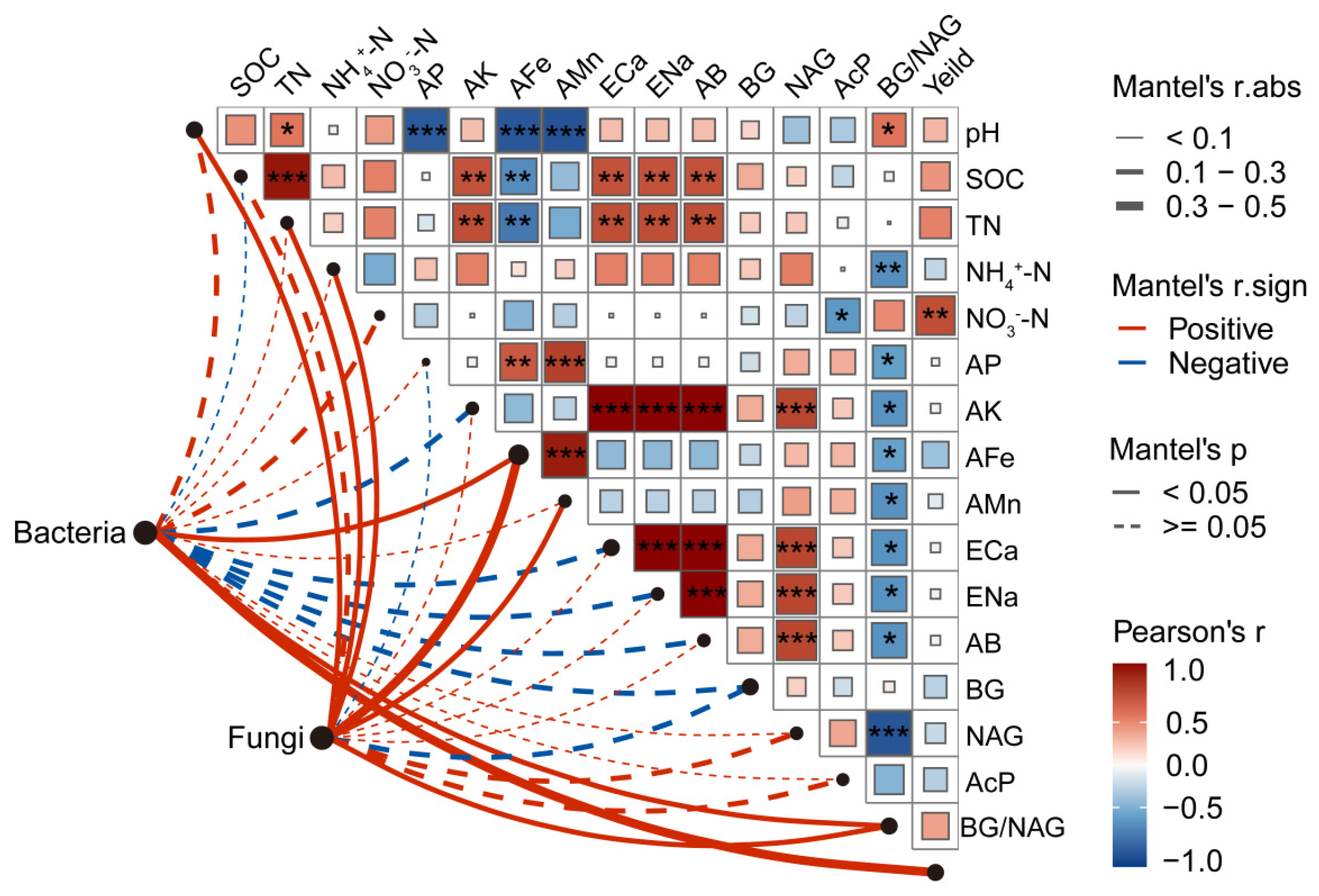

3.7. Regulatory Factors Influencing Soil Microbes

4. Discussion

4.1. Different Responses of Soil Nutrients and Mineral Elements to Understory Morel Cultivation

4.2. Diversified Responses of Soil Microbial Communities to Understory Morel Cultivation

4.3. Mechanisms of Carbon and Nitrogen Accumulation Under Conditions of Coexistence of Morels and Trees

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Du, X.; Zhao, Q.; Yang, Z.L. A review on research advances, issues, and perspectives of morels. Mycology 2015, 6, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masaphy, S. Biotechnology of morel mushrooms: Successful fruiting body formation and development in a soilless system. Biotechnol. Lett. 2010, 32, 1523–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brudvig, L.A.; Grman, E.; Habeck, C.W.; Orrock, J.L.; Ledvina, J.A. Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 310, 944–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, P.; Preece, C.; Peuelas, J.; Giri, J. Soil carbon sequestration by root exudates. Trends Plant Sci. 2022, 27, 749–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purahong, W.; Wubet, T.; Kahl, T.; Arnstadt, T.; Hoppe, B.; Lentendu, G.; Baber, K.; Rose, T.; Kellner, H.; Hofrichter, M.; et al. Increasing N deposition impacts neither diversity nor functions of deadwood-inhabiting fungal communities, but adaptation and functional redundancy ensure ecosystem function. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 20, 1693–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frac, M.; Hannula, S.E.; Belka, M.; Jedryczka, M. Fungal Biodiversity and Their Role in Soil Health. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.; Kohler, A.; Duplessis, S. Living in harmony in the wood underground: Ectomycorrhizal genomics. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2007, 10, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M.; Zobel, M. How mycorrhizal associations drive plant population and community biology. Science 2020, 367, eaba1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xun, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Ren, Y.; Xiong, W.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, N.; Miao, Y.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, R. Specialized metabolic functions of keystone taxa sustain soil microbiome stability. Microbiome 2021, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilliam, F.S.; Hargis, E.A.; Rabinowitz, S.K.; Davis, B.C.; Sweet, L.L.; Moss, J.A. Soil microbiomes of hardwood- versus pine-dominated stands: Linkage with overstory species. Ecosphere 2023, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanek, M.; Kushwaha, P.; Murawska-Wlodarczyk, K.; Stefanowicz, A.M.; Babst-Kostecka, A. Quercus rubra invasion of temperate deciduous forest stands alters the structure and functions of the soil microbiome. Geoderma 2023, 430, 116328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Long, L.; Hu, Z.; Yu, X.; Liu, Q.; Bao, J.; Long, Z. Analyses of artificial morel soil bacterial community structure and mineral element contents in ascocarp and the cultivated soil. Can. J. Microbiol. 2019, 65, 738–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Liu, T.; Yu, Y.; Tang, J.; Jiang, L.; Martin, F.M.; Peng, W. Morel Production Related to Soil Microbial Diversity and Evenness. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e00229-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.W.; Jin, Z.X.; George, T.S.; Feng, G.; Zhang, L. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance plant phosphorus uptake through stimulating hyphosphere soil microbiome functional profiles for phosphorus turnover. New Phytol. 2023, 238, 2578–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wei, Y.; Lian, L.; Wei, B.; Bi, Y.; Liu, N.; Yang, G.; Zhang, Y. Macrofungi promote SOC decomposition and weaken sequestration by modulating soil microbial function in temperate steppe. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 899, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Ji, S.; Wu, D.; Zhu, M.; Lv, G. Effects of Root-Root Interactions on the Physiological Characteristics of Haloxylon ammodendron Seedlings. Plants 2024, 13, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelenik, S.; Perakis, S.; Hibbs, D. Regional constraints to biological nitrogen fixation in post-fire forest communities. Ecology 2013, 94, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subbarao, G.V.; Yoshihashi, T.; Worthington, M.; Nakahara, K.; Ando, Y.; Sahrawat, K.L.; Rao, I.M.; Lata, J.-C.; Kishii, M.; Braun, H.-J. Suppression of soil nitrification by plants. Plant Sci. 2015, 233, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tay, N.E.; Hopkins, A.J.M.; Ruthrof, K.X.; Burgess, T.; Hardy, G.E.S.; Fleming, P.A. The tripartite relationship between a bioturbator, mycorrhizal fungi, and a key Mediterranean forest tree. Austral. Ecol. 2018, 43, 742–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Tang, J.; Wang, Y.; He, X.; Tan, H.; Yu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Peng, W. Large-scale commercial cultivation of morels: Current state and perspectives. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 4401–4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, M.M.; Kakouridis, A.; Starr, E.; Nhu, N.; Shi, S.; Pett-Ridge, J.; Nuccio, E.; Zhou, J.; Firestone, M. Fungal-Bacterial Cooccurrence Patterns Differ between Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Nonmycorrhizal Fungi across Soil Niches. Mbio 2021, 12, 03509-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, H.; Chen, L.; Chen, W.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, X.; Su, K.; Zhao, Y. Characterization of mating-type idiomorphs suggests that Morchella importuna, Mel-20 and M-sextelata are heterothallic. Mycol. Prog. 2017, 16, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.W.; Fan, M.X.; Qin, H.Y.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Liu, S.J.; Wu, S.W.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, X. Interactions Between Morel Cultivation, Soil Microbes, and Mineral Nutrients: Impacts and Mechanisms. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.R. Estimation of Available Phosphorus in Soils by Extraction with Sodium Bicarbonate; US Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, M.; Shan, X.; Zhang, S.; Wen, B. Comparison of a rhizosphere-based method with other one-step extraction methods for assessing the bioavailability of soil metals to wheat. Chemosphere 2005, 59, 939–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, S.K.; Shukla, A.K.; Suresh, K.; Manorama, K.; Mathur, R.K.; Kumar, A.; Harinarayana, P.; Prakash, C.; Tripathi, A. Oil palm cultivation enhances soilpH, electrical conductivity, concentrations of exchangeable calcium, magnesium, and available sulfur and soil organic carbon content. Land Degrad. Dev. 2020, 31, 2789–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, X.; Chen, X.; Tang, M.; Ding, Z.; Jiang, L.; Li, P.; Ma, S.; Tian, D.; Xu, L.; Zhu, J.; et al. Nitrogen deposition has minor effect on soil extracellular enzyme activities in six Chinese forests. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 607, 806–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liang, C.; Mao, J.; Jiang, Y.; Bian, Q.; Liang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Sun, B. Microbial keystone taxa drive succession of plant residue chemistry. ISME J. 2023, 17, 748–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampt, E.A.; van Ruijven, J.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; Termorshuizen, A.J.; Mommer, L. Linking ecology and plant pathology to unravel the importance of soil-borne fungal pathogens in species-rich grasslands. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2019, 154, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Wagner, H. Vegan: Community Ecology R Package, v2.0-10. 2013. Available online: https://www.google.com.hk/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/vegan.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwiJ4aS55-aRAxVJ0DQHHZzXN7cQFnoECB8QAQ&usg=AOvVaw1WN4JmOwzwgBuLef_YXco0 (accessed on 26 December 2025).

- Liaw, A.; Wiener, M. Classification and regression by randomForest. R News 2002, 2/3, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Q.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, G. Patterns and drivers of atmospheric nitrogen deposition retention in global forests. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zong, N.; Song, M.; Shi, P.; Ma, W.; Fu, G.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, X.; Ouyang, H. Responses of ecosystem respiration and its components to fertilization in an alpine meadow on the Tibetan Plateau. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2013, 56, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.H.; Wei, Y.Q.; Lian, L.; Zhang, J.L.; Liu, N.; Wilson, G.W.T.; Rillig, M.C.; Jia, S.G.; Yang, G.W.; Zhang, Y.J. Discovering the role of fairy ring fungi in accelerating nitrogen cycling to in grasslands. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 199, 109595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKane, R.B.; Johnson, L.C.; Shaver, G.R.; Nadelhoffer, K.J.; Rastetter, E.B.; Fry, B.; Giblin, A.E.; Kielland, K.; Kwiatkowski, B.L.; Laundre, J.A.; et al. Resource-based niches provide a basis for plant species diversity and dominance in arctic tundra. Nature 2002, 415, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J.B.; Connolly, E.L. Plant-Soil Interactions: Nutrient Uptake. Nat. Educ. Knowl. 2013, 4, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, P.; Ding, Z.; Chen, G.; Wang, S.; Cheng, K.; Guo, C.; Li, X. Organic Carbon Sequestration by Secondary Fe–Mn Complex Minerals via the Anoxic Redox Reaction of Fe(II) and Birnessite. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 15128–15141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salas-Gonzalez, I.; Reyt, G.; Flis, P.; Custodio, V.; Gopaulchan, D.; Bakhoum, N.; Dew, T.P.; Suresh, K.; Franke, R.B.; Dangl, J.L.; et al. Coordination between microbiota and root endodermis supports plant mineral nutrient homeostasis. Science 2021, 371, eabd0695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bader, B.R.; Taban, S.K.; Fahmi, A.H.; Abood, M.A.; Hamdi, G.J. Potassium availability in soil amended with organic matter and phosphorous fertiliser under water stress during maize (Zea mays L) growth. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2021, 20, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Communar, G.; Keren, R. Boron adsorption by soils as affected by dissolved organic matter from treated sewage effluent. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2008, 72, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Shi, X.; Zhang, T.; An, H.; Hou, J.; Lan, H.; Zhao, P.; Hou, D.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J. Response of Soil Bacterial Communities and Potato Productivity to Fertilizer Application in Farmlands in the Agropastoral Zone of Northern China. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, W.; Ni, Z.; Hashidoko, Y.; Shen, W. Ammonium nitrogen content is a dominant predictor of bacterial community composition in an acidic forest soil with exogenous nitrogen enrichment. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 624, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Clarke, N. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungal Interacted with Biochar and Enhanced Phosphate-Solubilizing Microorganism Abundance and Phosphorus Uptake in Maize. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pold, G.; Domeignoz-Horta, L.A.; Morrison, E.W.; Frey, S.D.; Deangelis, K.M. Carbon Use Efficiency and Its Temperature Sensitivity Covary in Soil Bacteria. mBio 2020, 11, 02293-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei Ye, L.; Hong Bo, G.; Ke Xin, B.; Alekseevna, S.L.; Xiao Jian, Q.; Xiao Dan, Y. Determining why continuous cropping reduces the production of the morel Morchella sextelata. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 903983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, G.; Ye, J.; Wang, H.; He, H. Soil metagenomic analysis on changes of functional genes and microorganisms involved in nitrogen-cycle processes of acidified tea soils. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 998178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.W.; Riaz, M.; Yan, L.; Du, C.Q.; Liu, Y.L.; Jiang, C.C. Boron Deficiency in Trifoliate Orange Induces Changes in Pectin Composition and Architecture of Components in Root Cell Walls. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, V.N.L.; Dalal, R.C.; Greene, R.S.B. Carbon dynamics of sodic and saline soils following gypsum and organic material additions: A laboratory incubation. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2009, 41, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Hou, N.; Li, D. Remediation of soda-saline-alkali soil through soil amendments: Microbially mediated carbon and nitrogen cycles and remediation mechanisms. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 924, 171641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Xie, Z.; Li, P.; Chen, M.; Zhong, Z. A newly isolated indigenous metal-reducing bacterium induced Fe and Mn oxides synergy for enhanced in situ As (III/V) immobilization in groundwater. J. Hydrol. 2022, 608, 127635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melton, E.D.; Swanner, E.D.; Behrens, S.; Schmidt, C.; Kappler, A. The interplay of microbially mediated and abiotic reactions in the biogeochemical Fe cycle. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 12, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yuan, X.; Qin, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Fan, M.; Li, L.; Tian, L.; Fu, Y. Coupled Effects of Tree Species and Understory Morel on Modulating Soil Microbial Communities and Nutrient Dynamics. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010099

Yuan X, Qin H, Wang Y, Wu S, Zhang Z, Fan M, Li L, Tian L, Fu Y. Coupled Effects of Tree Species and Understory Morel on Modulating Soil Microbial Communities and Nutrient Dynamics. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010099

Chicago/Turabian StyleYuan, Xia, Haiyan Qin, Yun Wang, Shuwen Wu, Zeyu Zhang, Muxin Fan, Li Li, Liuqian Tian, and Yiwen Fu. 2026. "Coupled Effects of Tree Species and Understory Morel on Modulating Soil Microbial Communities and Nutrient Dynamics" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010099

APA StyleYuan, X., Qin, H., Wang, Y., Wu, S., Zhang, Z., Fan, M., Li, L., Tian, L., & Fu, Y. (2026). Coupled Effects of Tree Species and Understory Morel on Modulating Soil Microbial Communities and Nutrient Dynamics. Microorganisms, 14(1), 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010099