Risk Factors and Ocular Health Associated with Toxoplasmosis in Quilombola Communities

Abstract

1. Introduction

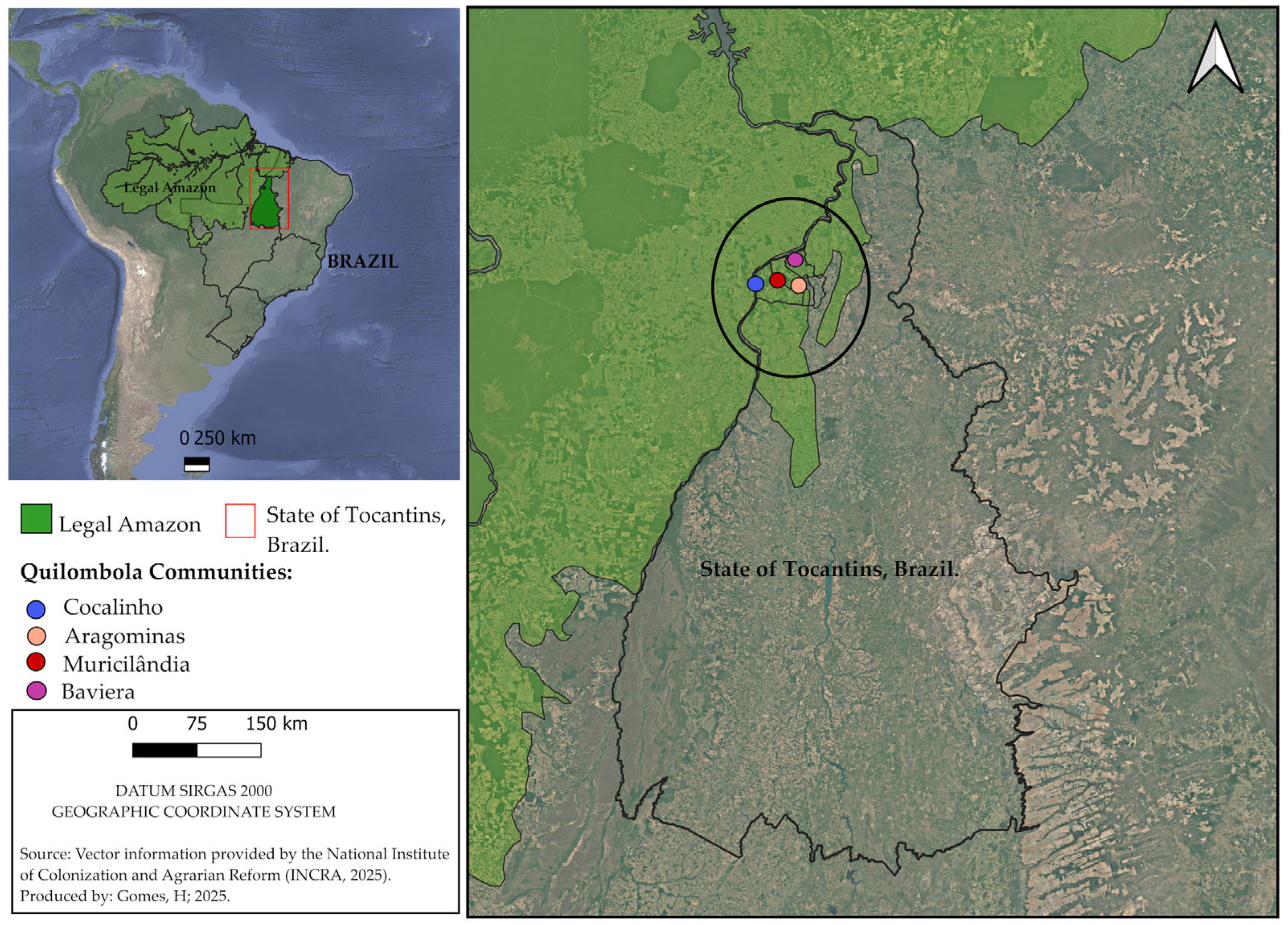

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Splendore, A. Un nuovo protozoa parasita de conigli incontrato nelle lesioni anatomiche d’una malattia che ricorda in molti punti il kala-azar dell’umo. Nota preliminare. Rev. Soc. Sci. São Paulo 1908, 3, 109–112. [Google Scholar]

- Panazzolo, G.K.; Kmetiuk, L.B.; Domingues, O.J.; Farinhas, J.H.; Doline, F.R.; de França, D.A.; Rodrigues, N.J.L.; Biondo, L.M.; Giuffrida, R.; Langoni, H.; et al. One Health Approach in Serosurvey of Toxoplasma gondii in Former Black Slave (Quilombola) Communities in Southern Brazil and Among Their Dogs. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remington, J.S.; Macleod, R.; Thulliez, P.; Desmonts, G. Toxoplasmosis. In Infectious Diseases of the Fetus and Newborn, 7th ed.; Remington, J.S., Klein, J.O., Wilson, C.B., Nizet, V., Maldonado, Y.A., Eds.; W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011; pp. 918–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, M.F.; Harun, A.B.; Hossain, D.; Bristi, S.Z.T.; Uddin, A.H.M.M.; Karim, M.R. Toxoplasmosis in animals and humans: A neglected zoonotic disease in Bangladesh. J. Parasit. Dis. 2024, 48, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoli, A.; Olfatifar, M.; Eslahi, A.V.; Moghadamizad, Z.; Samimi, R.; Habibi, M.A.; Kianimoghadam, A.S.; Badri, M.; Karanis, P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of protozoan parasite infections among patients with mental health disorders: An overlooked phenomenon. Gut Pathog. 2024, 16, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cifuentes-González, C.; Rojas-Carabali, W.; Olate Pérez, Á.; Carvalho, É.; Valenzuela, F.; Miguel-Escuder, L.; Ormaechea, M.S.; Heredia, M.; Baquero-Ospina, P.; Adan, A.; et al. Risk factors for recurrences and visual impairment in patients with ocular toxoplasmosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, P.S.; Scussel, A.C.M.O.; Silva, R.J.; Araújo, T.E.; Gonzaga, H.T.; Marcon, C.F.; Brito-de-Sousa, J.P.; Diniz, A.L.D.; Paschoini, M.C.; Barbosa, B.F.; et al. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Congenital Toxoplasmosis Diagnosis: Advances and Challenges. J. Trop. Med. 2024, 1, 1514178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milne, G.C.; Webster, J.P.; Walker, M. Is the incidence of congenital toxoplasmosis declining? Trends Parasitol. 2023, 39, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.; Souza, B. Quilombos no Brasil e nas Américas: Resistência Negra em Perspectiva Histórica. Agrar. Sul J. Polit. Econ. 2022, 11, 112–133. [Google Scholar]

- Freitas, D.A.; Caballero, A.D.; Marques, A.S.; Hernández, C.I.V.; Antunes, S.L.N.O. Saúde e comunidades quilombolas: Uma revisão da literatura. Rev. CEFAC 2011, 13, 937–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobe. Available online: https://www.strobe-statement.org/checklists/ (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Gubert, M.B.; Segall-Corrêa, A.M.; Spaniol, A.M.; Pedroso, J.; Coelho, S.E.; Pérez-Escamilla, R. Insegurança alimentar domiciliar em comunidades de descendentes de negros escravizados no Brasil: O legado da escravidão realmente acabou? Nutr. Em Saúde Pública 2017, 20, 1513–1522. [Google Scholar]

- Friesema, I.H.M.; Waap, H.; Swart, A.; Györke, A.; Le, R.D.; Evangelista, F.M.D.; Spano, F.; Schares, G.; Deksne, G.; Gargaté, M.J.; et al. Systematic review and modelling of Toxoplasma gondii seroprevalence in humans, Europe, 2000 to 2021. Euro Surveill 2025, 30, 2500069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahadori, A.; Babazadeh, T.; Chollou, K.M.; Moqadam, H.; Zendeh, M.B.; Valipour, B.; Valizadeh, L.; Valizadeh, S.; Abolhasani, S.; Behniafar, H. Seroprevalence and risk factors associated with toxoplasmosis in nomadic, rural, and urban communities of northwestern Iran. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1516693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doline, F.R.; Farinhas, J.H.; Biondo, L.M.; Oliveira, P.R.F.; Rodrigues, N.J.L.; Patrício, K.P.; Mota, R.A.; Langoni, H.; Pettan-Brewer, C.; Giuffrida, R.; et al. Toxoplasma gondii exposure in Brazilian indigenous populations, their dogs, environment, and healthcare professionals. One Health 2023, 16, 100567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmanian, V.; Rahmanian, K.; Jahromi, A.S.; Bokaie, S. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii infection: An umbrella review of updated systematic reviews and meta-analyses. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 3848–3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, T.; Ijaz, S.; Afzal, M.; Ijaz, N. Serological detection of Toxoplasma gondii and associated risk factors among pregnant women in Lahore Pakistan. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 101, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Martínez, S.; Pérez-Álamos, A.R.; Ibarra-Segovia, M.; Beristaín-Garcia, I.; Ramos-Nevárez, A.; Saenz-Soto, L.; Rábago-Sánchez, E.; Guido-Arreola, C.A.; Alvarado-Esquivel, C. Seroepidemiology of Toxoplasma gondii infection in people with alcohol consumption in Durango, Mexico. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assoni, L.C.P.; Nakashima, F.; Sousa, V.P.; Paduan, N.J.; Andreasse, I.R.; Anghinoni, T.H.; Junior, G.M.F.; Ricci Junior, O.; Castiglioni, L.; Brandão, C.C.; et al. Soroepidemiologia da infecção por Toxoplasma gondii em doadores de sangue em uma população da região noroeste do estado de São Paulo, Brasil. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2024, 118, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boussalem, H.; Chahed, C.; Brahem, H.; Gamha, W.; Mahjoub, W.; Touati, H.; Ghezal, L.; Essid, S.; Loghmari, E.; Guezguez, L.; et al. Seroprevalence and risk factors of toxoplasmosis among pregnant women in the M’saken region (Tunisia). Clin. Chim. Acta 2024, 558, 119189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menajovsky, M.F.; Espunyes, J.; Ulloa, G.; Calderon, M.; Diestra, A.; Malaga, E.; Muñoz, C.; Montero, S.; Lescano, A.G.; Santolalla, M.L.; et al. Toxoplasma gondii in a Remote Subsistence Hunting-Based Indigenous Community of the Peruvian Amazon. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2024, 9, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calero-Bernal, R.; Gennari, S.M.; Cano, S.; Salas-Fajardo, M.Y.; Ríos, A.; Álvarez-García, G.; Ortega-Mora, L.M. Anti-Toxoplasma gondii Antibodies in European Residents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Studies Published between 2000 and 2020. Pathogens 2023, 8, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, L.; Seeber, F.; Aebischer, A.; Kuhnert, R.; Schlaud, M.; Stark, K.; Wilking, H. Toxoplasma gondii Infections and Associated Factors in Female Children and Adolescents, Germany. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 995–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassie, E.; Kebede, N.; Kassa, T.; Garoma, A.; Girma, M.; Asnake, Y.; Alemu, A.; Degu, S.; Tsigie, M. Seroprevalence and risk factors for Toxoplasma gondii infection among pregnant women at Debre Markos Referral Hospital, northwest Ethiopia. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2024, 118, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montalbano, G.; Kung, V.M.; Franco-Paredes, C.; Barahona, L.V.; Chastain, D.B.; Tuells, J.; Henao-Martínez, A.F.; Montoya, J.G.; Reno, E. Positive Toxoplasma IgG Serology Is Associated with Increased Overall Mortality—A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2024, 110, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khairullah, A.R.; Kurniawan, S.C.; Widodo, A.; Effendi, M.H.; Hasib, A.; Silaen, O.S.M.; Ramandinianto, S.C.; Moses, I.B.; Riwu, K.H.P.; Yanestria, S.M.; et al. A Comprehensive Review of Toxoplasmosis: Serious Threat to Human Health. Open Public Health J. 2024, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quites, H.F.O. Fatores associados à infecção com Toxoplasma gondii em comunidade rural do Vale do Jequitinhonha, Minas Gerais. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Velasco-Velásquez, S.; Orozco, A.S.; Ramirez, M.; Pachón, L.; Hurtado-Gomez, M.J.; Valois, G.; Celis-Giraldo, D.; Cordero-López, S.S.; McLeod, R.; Gómez-Marín, J.E. Impact of education on knowledge, attitudes, and practices for gestational toxoplasmosis. J. Infect. Public Health 2024, 17, 102516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzgar, G.; Ahmadpour, E.; Kohansal, M.H.; Moghaddam, S.M.; Koski, T.J.; Barac, A.; Nissapatorn, V.; Paul, A.K.; Micic, J. Seroprevalence and risk factors of Toxoplasma gondii infection among pregnant women. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2024, 18, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebaa, S.; Behnke, J.M.; Labed, A.; Abu-Madi, M.A. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii and Associated Risk Factors among Pregnant Women in Algeria. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2024, 110, 1137–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubey, J.P.; Lindsay, D.S.; Speer, C.A. Structures of Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites, bradyzoites, and sporozoites and biology and development of tissue cysts. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1998, 11, 267–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.-Y.; Remington, J.S. Toxoplasmosis in Pregnancy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1994, 18, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Perez, L.; Rico Torres, C.P.; Valenzuela Moreno, L.F.; Cedillo-Pelaez, C.; Caballero-Ortega, H.; Acosta-Salinas, R.; Villalobos, N.; Martínez Maya, J.J. Toxoplasmosis in cats from a dairy-producing region in Hidalgo, Mexico. Vet. México OA 2024, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed-Cherif, A.; Benfodil, K.; Ansel, S.; Ait-Oudhia, K.H. Seroprevalence and associated risk factors of Toxoplasma gondii infection in stray cats in Algiers urban area, Algeria. J. Hell. Vet. Med. Soc. 2020, 71, 2135–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruda, S.; Vieira, B.R.; Garcia, D.M.; Araújo, M.; Simôes, M.; Moreto, R.; Rodrigues, M.W., Jr.; Belfort, R., Jr.; Smith, J.R.; Furtado, J.M. Clinical manifestations and visual outcomes associated with ocular toxoplasmosis in a Brazilian population. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balikoglu, M.; Ozdal, P.; Ozdemir, P.; Kavuncu, S.; Ozturk, F. Prognostic factors for final visual acuity and recurrence in active ocular toxoplasmosis. J. Retin. Vitr. 2009, 17, 255–262. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch-Driessen, L.E.H.; Berendschot, T.T.J.M.; Ongkosuwito, J.V.; Rothova, A. Ocular toxoplasmosis: Clinical features and prognosis of 154 patients. Ophthalmology 2002, 109, 869–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch-Driessen, L.E.H.; Karimi, S.; Stilma, J.S.; Rothova, A. Retinal detachment in ocular toxoplasmosis. Ophthalmology 2000, 107, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandão-de-Resende, C.; Santos, H.H.; Lagos, A.A.R.; Lara, C.M.; Arruda, J.S.D.; Marino, A.P.M.P.; Antonelli, L.R.V.; Gazzinelli, R.T.; Vitor, R.W.A.; Vasconcelos-Santos, D.V. Clinical and Multimodal Imaging Findings and Risk Factors for Ocular Involvement in a Presumed Waterborne Toxoplasmosis Outbreak, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 2922–2932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulson, A.; Jacob, D.; Kishikova, L.; Saad, A. Toxoplasmosis Related Neuroretinitis: More than Meets the Eye. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2022, 30, 556–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyinloye, S.O.; Igila-Atsibee, M.; Ajayi, B.; Lawan, M.A. Serological screening for ante-natal toxoplasmosis in Maiduguri Municipal Council, Borno State, Nigeria. Afr. J. Clin. Exp. Microbiol. 2014, 15, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.R.; Ferreira, L.B.; Furtado, J.M.; Charng, J.; Franchina, M.; Molan, A.; Hunter, M.; Mackey, D.A. Prevalence of ocular toxoplasmosis in the Australian population. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2022, 49, 845–846. [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer, J.; Iliev, M.; Halberstadt, M.; Kodjikian, L.; Garweg, J.G. Visual function in human ocular toxoplasmosis. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2007, 91, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Test | Children | Elderly | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | OR | CI 95% | p | |

| IgG | 36/81 | 44.44 | 62/80 | 77.50 | 98/161 | 60.87 | 4.31 | 2.17–8.53 | <0.0001 |

| IgG and IgM | 2/81 | 2.47% | - | - | 2/161 | 1.24 | - | - | - |

| IgM | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| PCR | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total | 38/81 | 46.91 | 62/80 | 77.50 | 100/161 | 62.11 | 3.90 | 1.97–7.71 | 0.0001 |

| n (Positive)/Total Children | n (Negative)/Total Children | OR | CI 95% | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||||

| Has cats | Yes | 23 | 60.53 | 10 | 23.25 | 5.06 | 1.93–13.23 | 0.001 |

| No | 15 | 39.47 | 33 | 76.74 | ||||

| Has a garden | Yes | 25 | 65.79 | 15 | 34.88 | 3.59 | 1.43–8.99 | 0.005 |

| No | 13 | 34.21 | 28 | 65.12 | ||||

| Plays in the soil | Yes | 35 | 92.11 | 21 | 95.35 | 12.22 | 3.26–45.85 | 0.0001 |

| No | 3 | 7.89 | 22 | 4.65 | ||||

| n (Positive)/Total Elderly | n (Negative)/Total Elderly | OR | CI 95% | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||||

| Has a garden | Yes | 40 | 64.52 | 5 | 50.00 | 4.73 | 1.49–15.00 | 0.013 |

| No | 22 | 35.48 | 13 | 50.00 | ||||

| Has a yard with soil | Yes | 57 | 91.94 | 11 | 61.11 | 7.25 | 1.94–27.08 | 0.004 |

| No | 5 | 8.06 | 7 | 38.89 | ||||

| Has cats | Yes | 40 | 64.52 | 5 | 27.78 | 4.72 | 1.49–15.01 | 0.013 |

| No | 22 | 35.48 | 13 | 72.22 | ||||

| n (Positive)/Total | n (Negative)/Total | OR | CI 95% | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |||||

| Age | ≥5 ≤ 7 | 38 | 38.00 | 43 | 70.49 | 4.07 | 2.05–8.06 | 0.00004 |

| ≥60 | 62 | 62.00 | 18 | 29.51 | ||||

| Distance visual acuity | 20/20 | 34 | 34.00 | 31 | 50.82 | - | - | - |

| 20/30–20/60 | 21 | 21.00 | 19 | 31.15 | 1.01 | 0.46–2.22 | 0.458 | |

| 20/70–20/160 | 20 | 20.00 | 7 | 11.48 | 2.60 | 0.97–7.00 | 0.089 | |

| 20/200–20/400 | 8 | 8.00 | 2 | 3.28 | 3.65 | 0.72–15.50 | 0.193 | |

| Blindness | 12 | 12.00 | 1 | 1.64 | 10.94 | 1.34–89.10 | 0.018 | |

| Without light perception | 4 | 4.00 | 0 | 0.00 | - | - | - | |

| Luminous perception | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 1.64 | - | - | - | |

| Goes to a farm, ranch, or poultry farm | Yes | 51 | 51.00 | 41 | 67.21 | 0.51 | 0.26–0.98 | 0.044 |

| No | 49 | 49.00 | 20 | 32.79 | ||||

| Has any illness | Yes | 38 | 38.00 | 10 | 16.39 | 3.13 | 1.42–6.88 | 0.004 |

| No | 62 | 62.00 | 51 | 83.61 | ||||

| Has noticed any vision problems | Yes | 63 | 63.00 | 23 | 37.70 | 2.81 | 1.46–5.43 | 0.002 |

| No | 37 | 37.00 | 38 | 62.30 | ||||

| Lens | Opaque | 37 | 39.78 | 10 | 16.67 | 3.30 | 1.49–7.32 | 0.002 |

| Normal | 56 | 60.22 | 50 | 83.33 | ||||

| Parents’ education level | ≤8 years | 80 | 80.00 | 35 | 52.46 | 2.97 | 1.46–6.02 | 0.00004 |

| >8 years | 20 | 20.00 | 26 | 47.54 | ||||

| Spherical equivalent | Normal vision | 42 | 42.00 | 35 | 57.38 | - | - | - |

| Myopia | 31 | 31.00 | 8 | 13.11 | 3.23 | 1.32–7.92 | 0.015 | |

| Hyperopia | 27 | 27.00 | 18 | 29.51 | 1.25 | 0.59–2.64 | 0.691 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Filho, S.C.C.; Moron, S.E.; Ferreira, R.G.; Gomes, H.; Costa, N.M.E.P.d.L.d.; Cangussu, A.S.R.; Ribeiro, B.M.; Campos, F.S.; Santos, G.R.d.; Aguiar, R.W.d.S.; et al. Risk Factors and Ocular Health Associated with Toxoplasmosis in Quilombola Communities. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010096

Filho SCC, Moron SE, Ferreira RG, Gomes H, Costa NMEPdLd, Cangussu ASR, Ribeiro BM, Campos FS, Santos GRd, Aguiar RWdS, et al. Risk Factors and Ocular Health Associated with Toxoplasmosis in Quilombola Communities. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):96. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010096

Chicago/Turabian StyleFilho, Silvio Carneiro Cunha, Sandro Esteban Moron, Raphael Gomes Ferreira, Helierson Gomes, Noé Mitterhofer Eiterer Ponce de Leon da Costa, Alex Sander Rodrigues Cangussu, Bergmann Morais Ribeiro, Fabricio Souza Campos, Gil Rodrigues dos Santos, Raimundo Wagner de Souza Aguiar, and et al. 2026. "Risk Factors and Ocular Health Associated with Toxoplasmosis in Quilombola Communities" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010096

APA StyleFilho, S. C. C., Moron, S. E., Ferreira, R. G., Gomes, H., Costa, N. M. E. P. d. L. d., Cangussu, A. S. R., Ribeiro, B. M., Campos, F. S., Santos, G. R. d., Aguiar, R. W. d. S., Costa, T. R., Oliveira, E. C. A. M., Pinheiro, J. D., Eugênio, F., Gontijo, E. E. L., Sousa, S. F. d., & Silva, M. G. d. (2026). Risk Factors and Ocular Health Associated with Toxoplasmosis in Quilombola Communities. Microorganisms, 14(1), 96. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010096