High-Altitude Extreme Environments Drive Convergent Evolution of Skin Microbiota in Humans and Horses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Next-Generation Sequencing of 16S Full Length and Bioinformatics

2.3. Statistics

3. Results

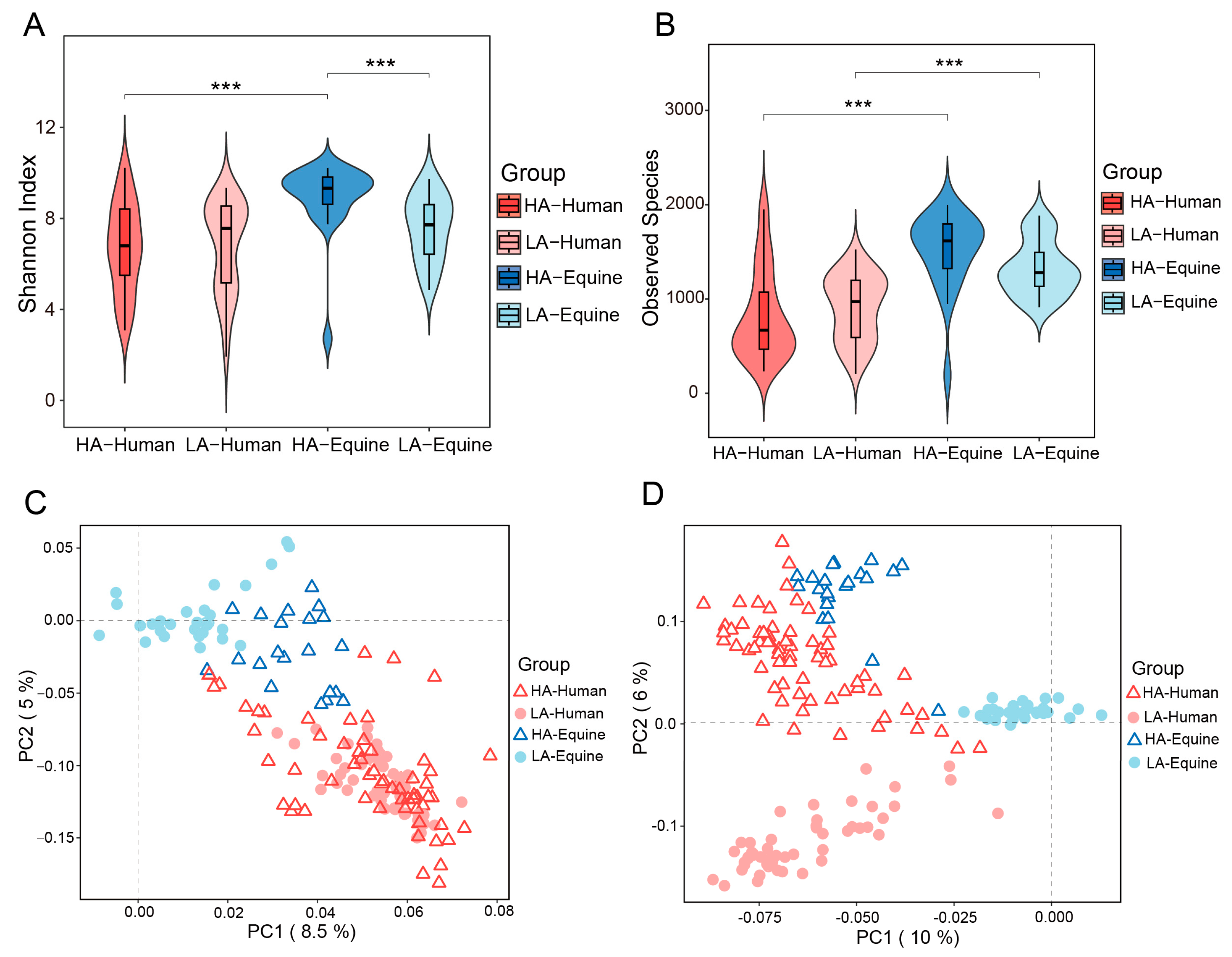

3.1. Altitude Affects the Diversity of Skin Microbiota of Humans and Horses Living at Different Altitudes

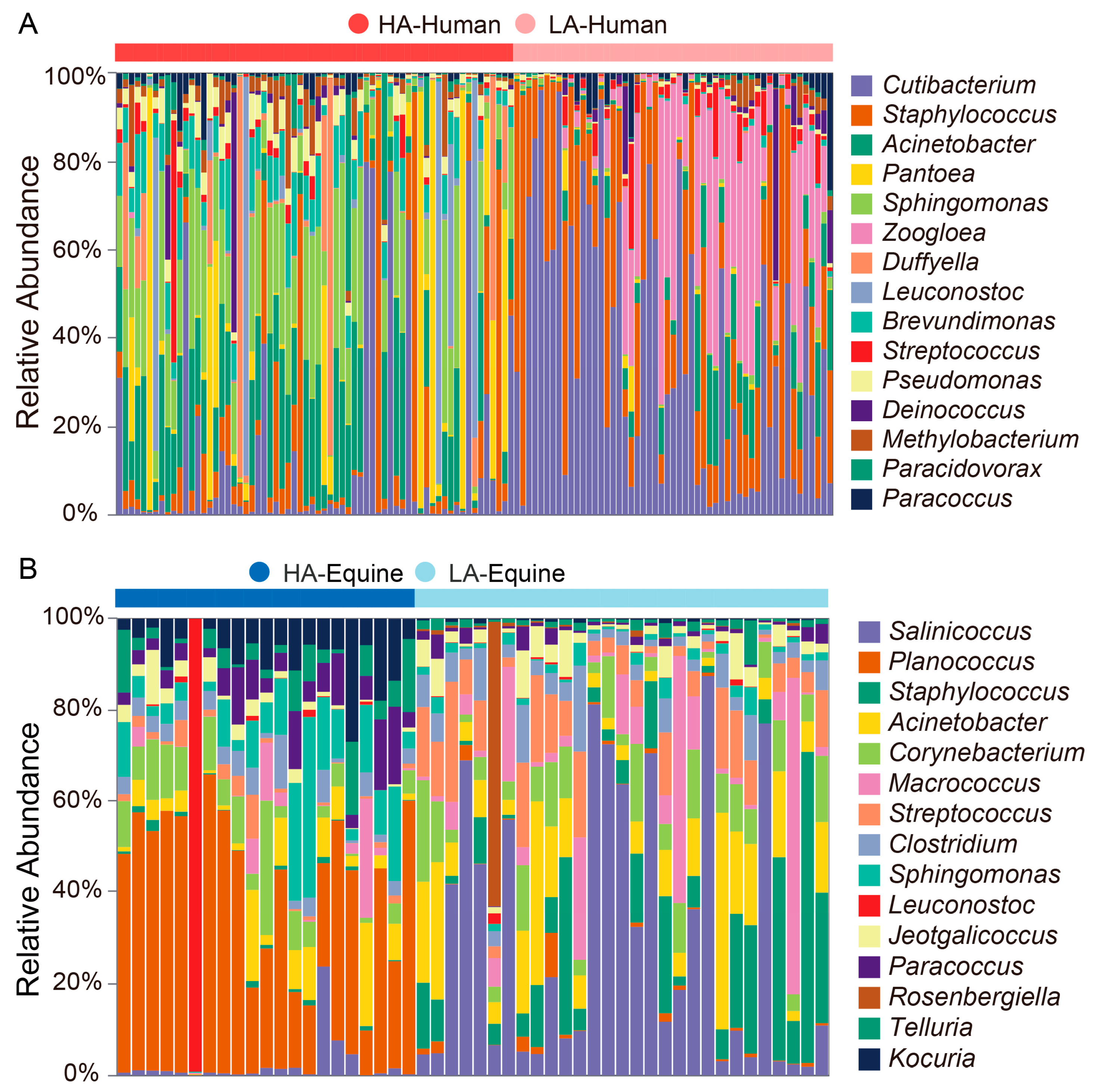

3.2. Bacterial Taxonomic Identification Associated with Altitudes and Species

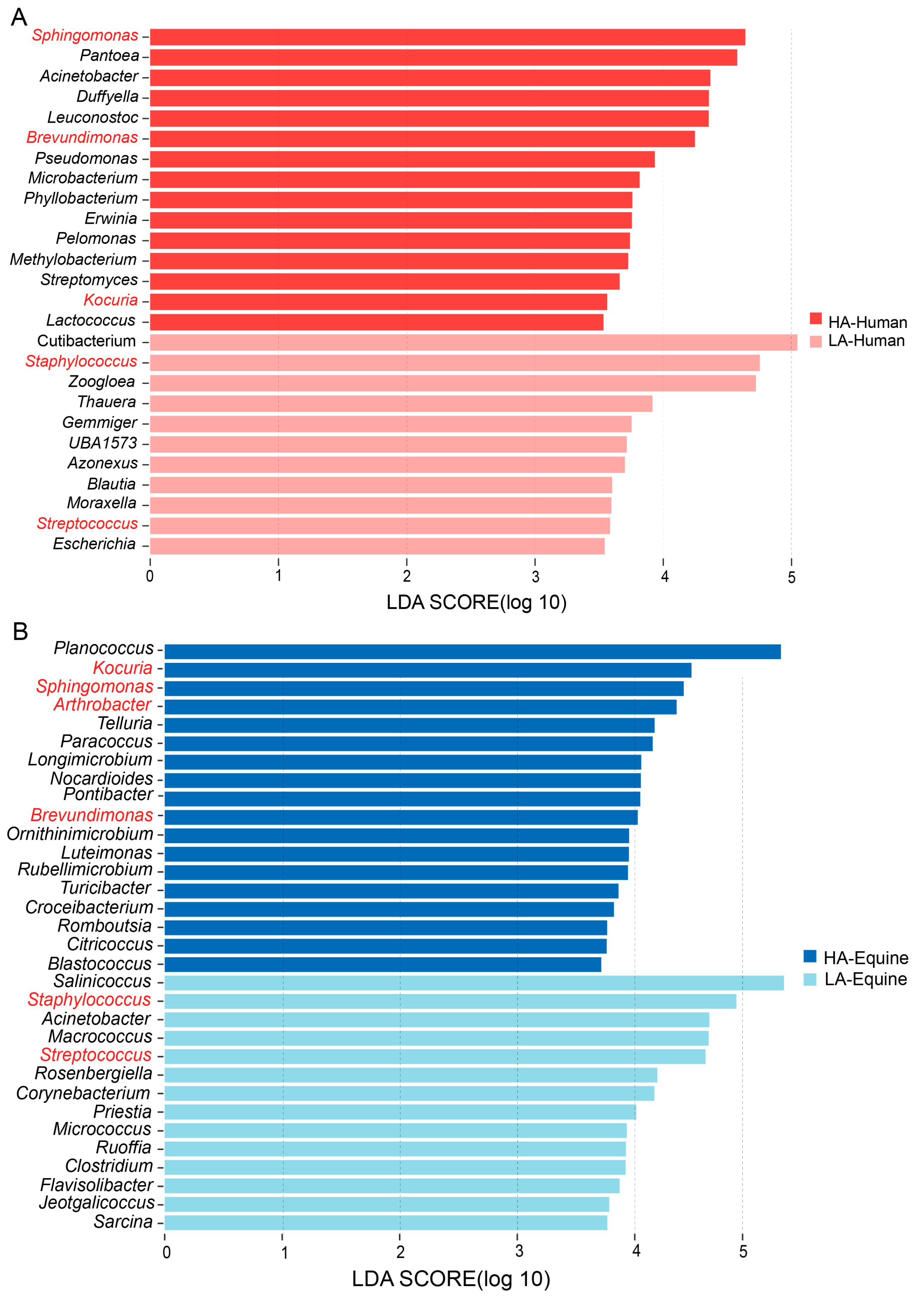

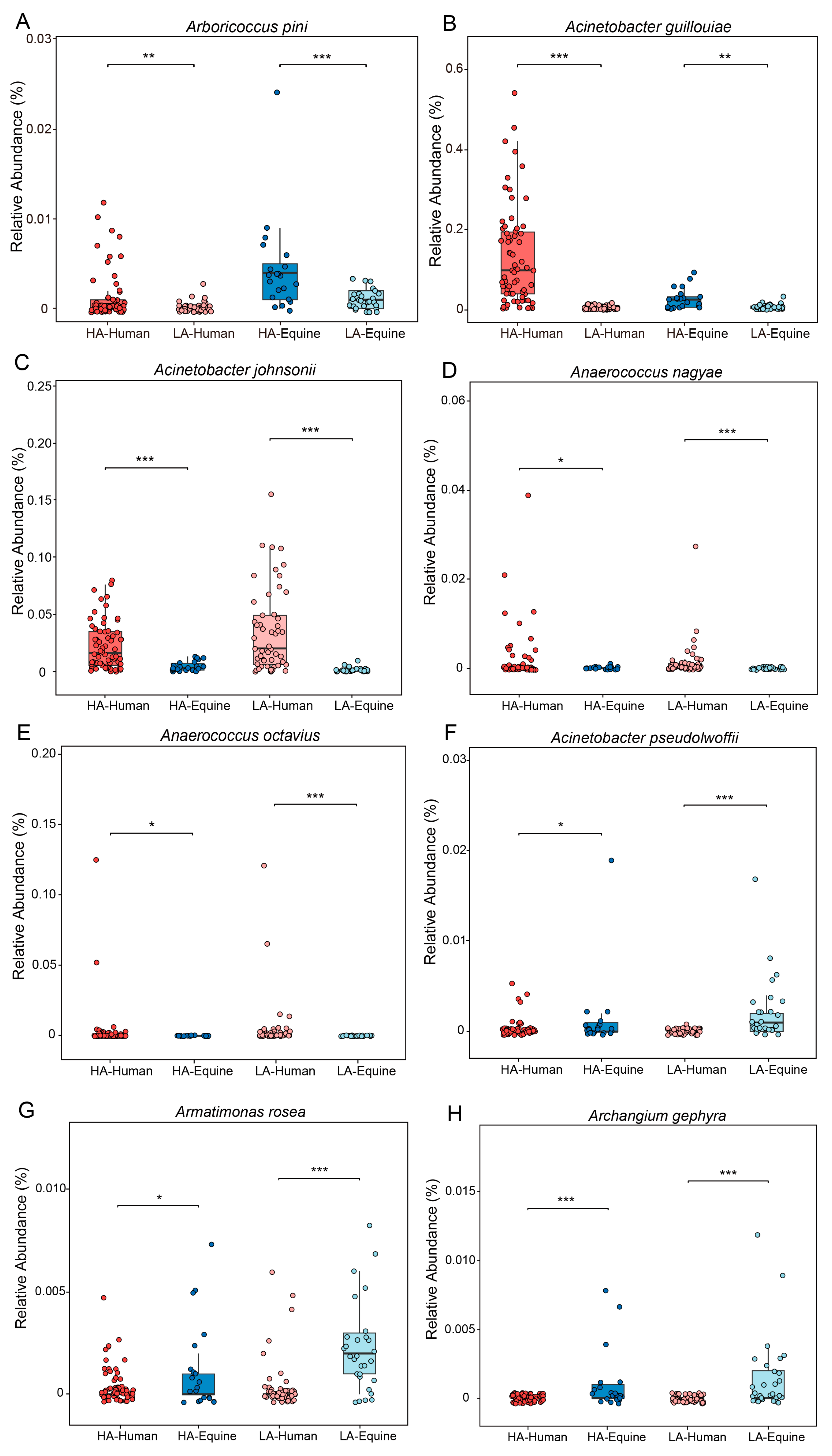

3.3. Signature Bacteria Differentiating Altitudes and Species

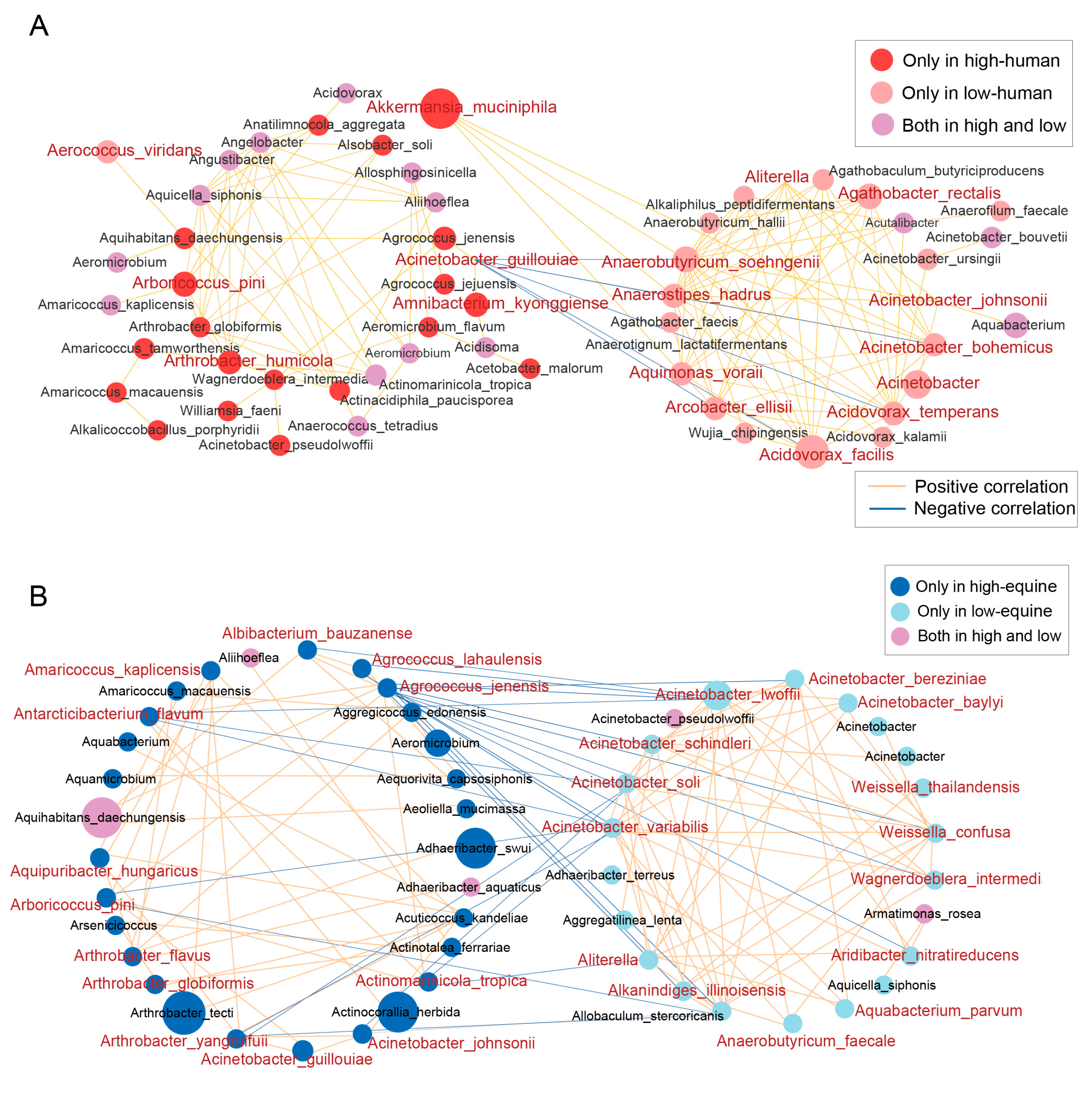

3.4. Multiple Taxonomic Treatments Associated with High- and Low-Altitude Samples Show Strong Positive Correlations Respectively

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, S.; Zhong, H.; He, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, L.; Xiong, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, N.; Morgavi, D.P.; Wang, J. Leveraging core enzyme structures for microbiota targeted functional regulation: Urease as an example. Imeta 2025, 4, e70032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshio, H.; Lagercrantz, H.; Gudmundsson, G.H.; Agerberth, B. First line of defense in early human life. Semin. Perinatol. 2004, 28, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, A.A.; Doxey, A.C.; Neufeld, J.D. The Skin Microbiome of Cohabiting Couples. mSystems 2017, 2, e00043-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smythe, P.; Wilkinson, H.N. The Skin Microbiome: Current Landscape and Future Opportunities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moissl-Eichinger, C.; Probst, A.J.; Birarda, G.; Auerbach, A.; Koskinen, K.; Wolf, P.; Holman, H.N. Human age and skin physiology shape diversity and abundance of Archaea on skin. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, J.; Byrd, A.L.; Park, M.; Kong, H.H.; Segre, J.A. Temporal Stability of the Human Skin Microbiome. Cell 2016, 165, 854–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grice, E.A.; Segre, J.A. The skin microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kortekaas Krohn, I.; Callewaert, C.; Belasri, H.; De Pessemier, B.; Diez Lopez, C.; Mortz, C.G.; O’Mahony, L.; Pérez-Gordo, M.; Sokolowska, M.; Unger, Z.; et al. The influence of lifestyle and environmental factors on host resilience through a homeostatic skin microbiota: An EAACI Task Force Report. Allergy 2024, 79, 3269–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, J.; Kim, T.G.; Ryu, J.H. Conversation between skin microbiota and the host: From early life to adulthood. Exp. Mol. Med. 2025, 57, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunjani, N.; Ahearn-Ford, S.; Dube, F.S.; Hlela, C.; O’Mahony, L. Mechanisms of microbe-immune system dialogue within the skin. Genes Immun. 2021, 22, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefèvre-Utile, A.; Braun, C.; Haftek, M.; Aubin, F. Five Functional Aspects of the Epidermal Barrier. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mead, M.N. Nutrigenomics: The genome–food interface. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, A582–A589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Tseng, C.H.; Strober, B.E.; Pei, Z.; Blaser, M.J. Substantial alterations of the cutaneous bacterial biota in psoriatic lesions. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grice, E.A.; Kong, H.H.; Renaud, G.; Young, A.C.; Bouffard, G.G.; Blakesley, R.W.; Wolfsberg, T.G.; Turner, M.L.; Segre, J.A. A diversity profile of the human skin microbiota. Genome Res. 2008, 18, 1043–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszkowski, W.; Roszkowski, K.; Ko, H.L.; Beuth, J.; Jeljaszewicz, J. Immunomodulation by propionibacteria. Zentralbl Bakteriol. 1990, 274, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.W.; Stratton, C.W. Staphylococcus aureus: An old pathogen with new weapons. Clin. Lab. Med. 2010, 30, 179–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; Han, Y.; Li, M.; Peng, Y.; Chai, J.; Yang, G.; Li, Y.; Zhao, J. HiFi based metagenomic assembly strategy provides accuracy near isolated genome resolution in MAG assembly. iMetaOmics 2025, 2, e70041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, M.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Kuo, S.; Coda, A.; Jiang, Y.; Gallo, R.L.; Huang, C.M. Fermentation of Propionibacterium acnes, a commensal bacterium in the human skin microbiome, as skin probiotics against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Kuo, S.; Shu, M.; Yu, J.; Huang, S.; Dai, A.; Two, A.; Gallo, R.L.; Huang, C.M. Staphylococcus epidermidis in the human skin microbiome mediates fermentation to inhibit the growth of Propionibacterium acnes: Implications of probiotics in acne vulgaris. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knackstedt, R.; Knackstedt, T.; Gatherwright, J. The role of topical probiotics in skin conditions: A systematic review of animal and human studies and implications for future therapies. Exp. Dermatol. 2020, 29, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beall, C.M. Andean, Tibetan, and Ethiopian patterns of adaptation to high-altitude hypoxia. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2006, 46, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jablonski, N.G.; Chaplin, G. Colloquium paper: Human skin pigmentation as an adaptation to UV radiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 8962–8968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, C.M.; Wilson, L.F.; Green, A.C.; Bain, C.J.; Fritschi, L.; Neale, R.E.; Whiteman, D.C. Cancers in Australia attributable to exposure to solar ultraviolet radiation and prevented by regular sunscreen use. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2015, 39, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Q.; Feng, T.; Zhou, R.; Shao, L.; Qu, J.; Li, N.; Bo, T.; Zhou, H. Elevation is Associated with Human Skin Microbiomes. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, B.; Zhao, J.; Guo, W.; Zhang, S.; Hua, Y.; Tang, J.; Kong, F.; Yang, X.; Fu, L.; Liao, K.; et al. High-Altitude Living Shapes the Skin Microbiome in Humans and Pigs. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Ran, H.; Hua, Y.; Deng, F.; Zeng, B.; Chai, J.; Li, Y. Screening and evaluation of skin potential probiotic from high-altitude Tibetans to repair ultraviolet radiation damage. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1273902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zheng, J.; Mao, H.; Vinitchaikul, P.; Wu, D.; Chai, J. Multiomics of yaks reveals significant contribution of microbiome into host metabolism. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.; Wang, C.; Li, D.; Peng, Y.; Deng, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, M.; Wu, K.; Zhao, J.; et al. The unique gut microbiome of giant pandas involved in protein metabolism contributes to the host’s dietary adaption to bamboo. Microbiome 2023, 11, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizley, S.C.; Dudhia, J.; Smith, R.K.W.; Williams, A.C. Transdermal drug delivery in horses: An in vitro comparison of skin structure and permeation of two model drugs at various anatomical sites. Vet. Dermatol. 2023, 34, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.S.; Spakowicz, D.J.; Hong, B.Y.; Petersen, L.M.; Demkowicz, P.; Chen, L.; Leopold, S.R.; Hanson, B.M.; Agresta, H.O.; Gerstein, M.; et al. Evaluation of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for species and strain-level microbiome analysis. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estaki, M.; Jiang, L.; Bokulich, N.A.; McDonald, D.; González, A.; Kosciolek, T.; Martino, C.; Zhu, Q.; Birmingham, A.; Vázquez-Baeza, Y.; et al. QIIME 2 Enables Comprehensive End-to-End Analysis of Diverse Microbiome Data and Comparative Studies with Publicly Available Data. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2020, 70, e100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, M.; Duncan, C.; Schaffer, P.A.; Wobeser, B.; Magzamen, S. Environmental risk factors for UV-induced cutaneous neoplasia in horses: A GIS approach. Can. Vet. J. 2023, 64, 971–975. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, D.R.; McCutcheon, L.J.; Byrd, S.K.; Brown, W.S.; Bayly, W.M.; Brengelmann, G.L.; Gollnick, P.D. Dissipation of metabolic heat in the horse during exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 1993, 74, 1161–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, Q.; Zhou, R.; Feng, T.; Hilal, M.G.; Li, H. Nationality and body location alter human skin microbiome. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 5241–5256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grice, E.A.; Kong, H.H.; Conlan, S.; Deming, C.B.; Davis, J.; Young, A.C.; Bouffard, G.G.; Blakesley, R.W.; Murray, P.R.; Green, E.D.; et al. Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science 2009, 324, 1190–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.; Arellano, K.; Lee, Y.; Yeo, S.; Ji, Y.; Ko, J.; Holzapfel, W. Pilot Study on the Forehead Skin Microbiome and Short Chain Fatty Acids Depending on the SC Functional Index in Korean Cohorts. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, C.; Rusling, M.; Lampeter, T.; Love, C.; Karim, A.; Bongiorno, C.; Yuan, L.L. Automation of QIIME2 Metagenomic Analysis Platform. Curr. Protoc. 2021, 1, e254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, R.C.; Haas, B.J.; Clemente, J.C.; Quince, C.; Knight, R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2194–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Garrity, G.M.; Tiedje, J.M.; Cole, J.R. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 5261–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P.; De Cáceres, M. Beta diversity as the variance of community data: Dissimilarity coefficients and partitioning. Ecol. Lett. 2013, 16, 951–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, J.R.; Curtis, J.T. An Ordination of the Upland Forest Communities of Southern Wisconsin. Ecol. Monogr. 1957, 27, 325–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segata, N.; Izard, J.; Waldron, L.; Gevers, D.; Miropolsky, L.; Garrett, W.S.; Huttenhower, C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, H.; Dijkshoorn, L.; Gerner-Smidt, P.; Pelzer, N.; Tjernberg, I.; Vaneechoutte, M. Distribution of Acinetobacter species on human skin: Comparison of phenotypic and genotypic identification methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1997, 35, 2819–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloo, A.C.M.; de Vries, E.D.; Jean-Pierre, H.; van Winkelhoff, A.J. Anaerococcus nagyae sp. nov., isolated from human clinical specimens. Anaerobe 2016, 38, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, T.; Shinozaki, J.; Kajiura, T.; Iwasaki, K.; Fudou, R. A newly discovered Anaerococcus strain responsible for axillary odor and a new axillary odor inhibitor, pentagalloyl glucose. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2014, 89, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sladecek, V.; Senk, D.; Stolar, P.; Bzdil, J.; Holy, O. Predominance of Acinetobacter pseudolwoffii among Acinetobacter species in domestic animals in the Czech Republic. Vet. Med. 2023, 68, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamaki, H.; Tanaka, Y.; Matsuzawa, H.; Muramatsu, M.; Meng, X.Y.; Hanada, S.; Mori, K.; Kamagata, Y. Armatimonas rosea gen. nov., sp. nov., of a novel bacterial phylum, Armatimonadetes phyl. nov., formally called the candidate phylum OP10. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2011, 61, 1442–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, N.; Yang, X.; Yang, Q.; Guo, M. Comparative Genomic and Transcriptomic Analysis of Phenol Degradation and Tolerance in Acinetobacter lwoffii through Adaptive Evolution. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Capua, C.; Bortolotti, A.; Farías, M.E.; Cortez, N. UV-resistant Acinetobacter sp. isolates from Andean wetlands display high catalase activity. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2011, 317, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asker, D.; Beppu, T.; Ueda, K. Sphingomonas astaxanthinifaciens sp. nov., a novel astaxanthin-producing bacterium of the family Sphingomonadaceae isolated from Misasa, Tottori, Japan. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2007, 273, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishida, Y.; Adachi, K.; Kasai, H.; Shizuri, Y.; Shindo, K.; Sawabe, A.; Komemushi, S.; Miki, W.; Misawa, N. Elucidation of a carotenoid biosynthesis gene cluster encoding a novel enzyme, 2,2′-beta-hydroxylase, from Brevundimonas sp. strain SD212 and combinatorial biosynthesis of new or rare xanthophylls. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 4286–4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaeeyan, Z.; Safarpour, A.; Amoozegar, M.A.; Babavalian, H.; Tebyanian, H.; Shakeri, F. High carotenoid production by a halotolerant bacterium, Kocuria sp. strain QWT-12 and anticancer activity of its carotenoid. EXCLI J. 2017, 16, 840–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paredes Contreras, B.V.; Vermelho, A.B.; Casanova, L.; de Alencar Santos Lage, C.; Spindola Vilela, C.L.; da Silva Cardoso, V.; Pacheco Arge, L.W.; Cardoso-Rurr, J.S.; Correa, S.S.; Passos De Mansoldo, F.R.; et al. Enhanced UV-B photoprotection activity of carotenoids from the novel Arthrobacter sp. strain LAPM80 isolated from King George Island, Antarctica. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seel, W.; Baust, D.; Sons, D.; Albers, M.; Etzbach, L.; Fuss, J.; Lipski, A. Carotenoids are used as regulators for membrane fluidity by Staphylococcus xylosus. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giani, M.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.M. Carotenoids as a Protection Mechanism against Oxidative Stress in Haloferax mediterranei. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, T.; Cui, X.; Xu, Y.; Hu, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, G.; Zhang, G. Sphingomonas radiodurans sp. nov., a novel radiation-resistant bacterium isolated from the north slope of Mount Everest. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2022, 72, 005312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, J.J.; Ekanayake-Mudiyanselage, S. Vitamin E in human skin: Organ-specific physiology and considerations for its use in dermatology. Mol. Aspects Med. 2007, 28, 646–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, Y. Ceramide signaling in mammalian epidermis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1841, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarracín, V.H.; Pathak, G.P.; Douki, T.; Cadet, J.; Borsarelli, C.D.; Gärtner, W.; Farias, M.E. Extremophilic Acinetobacter strains from high-altitude lakes in Argentinean Puna: Remarkable UV-B resistance and efficient DNA damage repair. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 2012, 42, 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muletz Wolz, C.R.; Yarwood, S.A.; Campbell Grant, E.H.; Fleischer, R.C.; Lips, K.R. Effects of host species and environment on the skin microbiome of Plethodontid salamanders. J. Anim. Ecol. 2018, 87, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Z.; Peng, Y.; Deng, F.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, M.; Song, B.; Kim, J.K.; Pan, J.H.; et al. High-Altitude Extreme Environments Drive Convergent Evolution of Skin Microbiota in Humans and Horses. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010057

Zhang Y, Zhang M, Zhao Z, Peng Y, Deng F, Jiang H, Zhang M, Song B, Kim JK, Pan JH, et al. High-Altitude Extreme Environments Drive Convergent Evolution of Skin Microbiota in Humans and Horses. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010057

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yuwei, Manyu Zhang, Zhengge Zhao, Yunjuan Peng, Feilong Deng, Hui Jiang, Meimei Zhang, Bo Song, Jae Kyeom Kim, Jeong Hoon Pan, and et al. 2026. "High-Altitude Extreme Environments Drive Convergent Evolution of Skin Microbiota in Humans and Horses" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010057

APA StyleZhang, Y., Zhang, M., Zhao, Z., Peng, Y., Deng, F., Jiang, H., Zhang, M., Song, B., Kim, J. K., Pan, J. H., Chai, J., & Li, Y. (2026). High-Altitude Extreme Environments Drive Convergent Evolution of Skin Microbiota in Humans and Horses. Microorganisms, 14(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010057