Sulfide Production and Microbial Dynamics in the Water Reinjection System from an Offshore Oil-Producing Platform

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field and Sampling Sites for Chemical and Culture-Based Microbiological Analyses

2.2. Chemical Analysis

2.3. Abundances of Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria (SRB) and Total Anaerobic Heterotrophic Bacteria (TAHB)

2.4. DNA Extraction for Molecular-Based Microbiome Analyses

2.5. Real-Time Quantitative PCR (qPCR)

2.6. Microbiome Analysis on the Basis of 16S rRNA Gene Sequences

3. Results

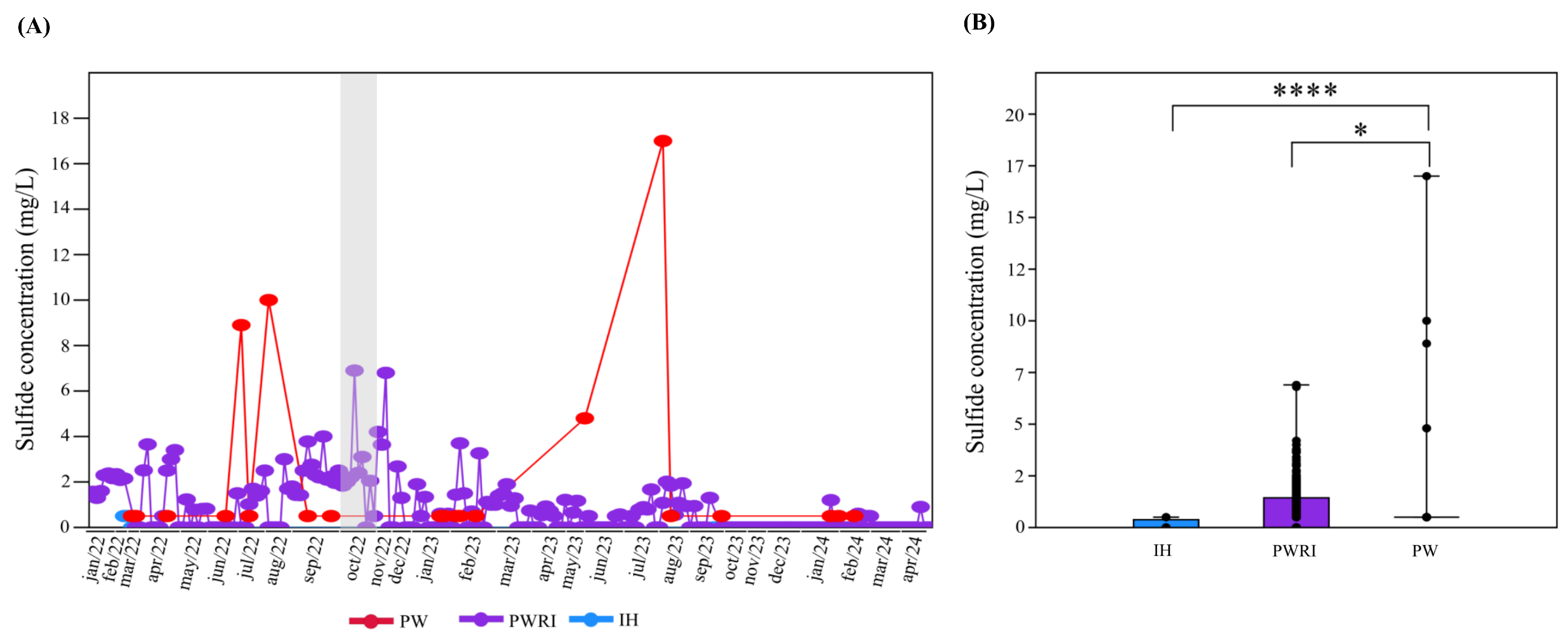

3.1. Analysis of H2S in the Oil Reservoir

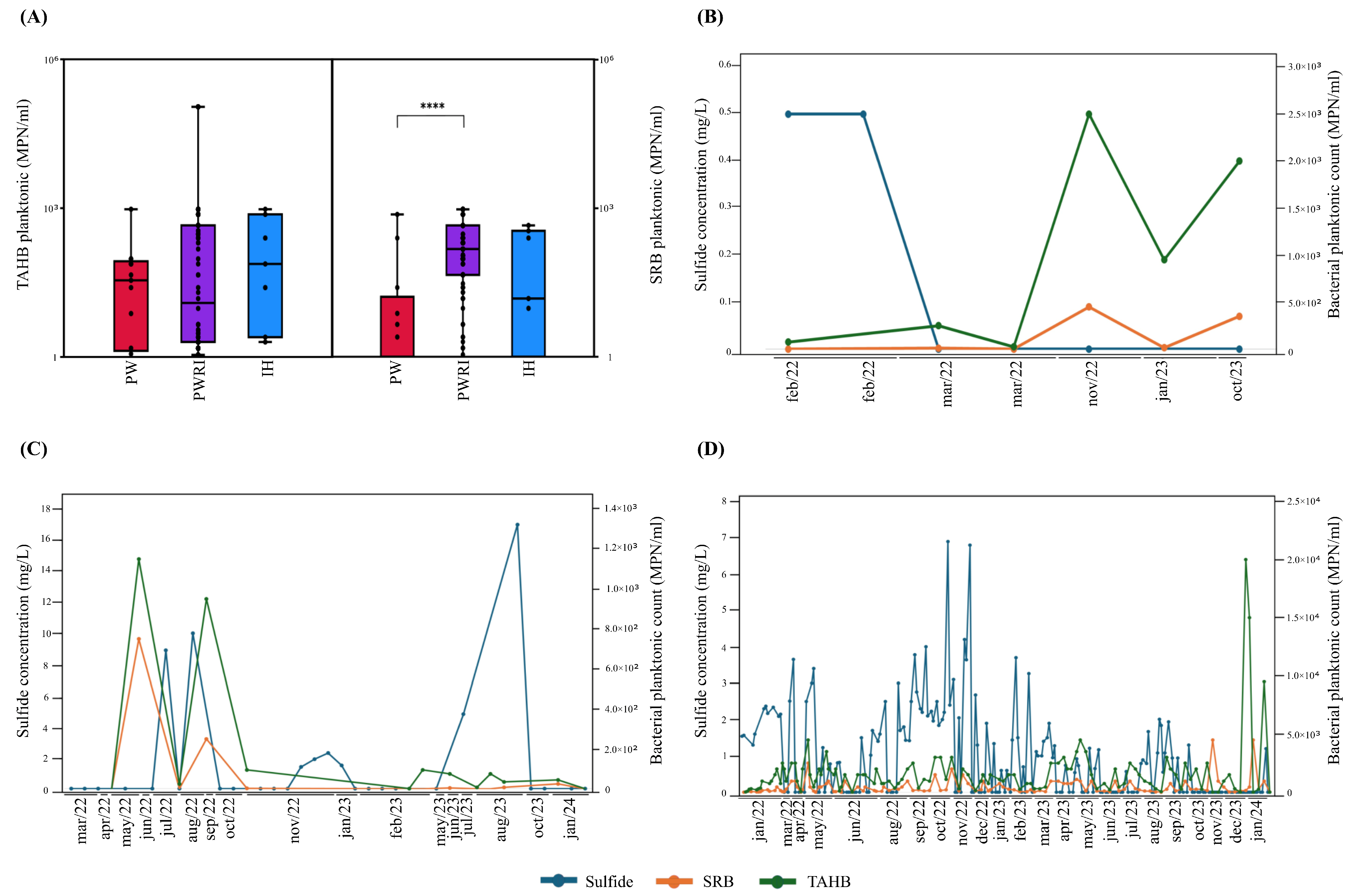

3.2. Abundances of SRB and TAHB in PW and PWRI Samples

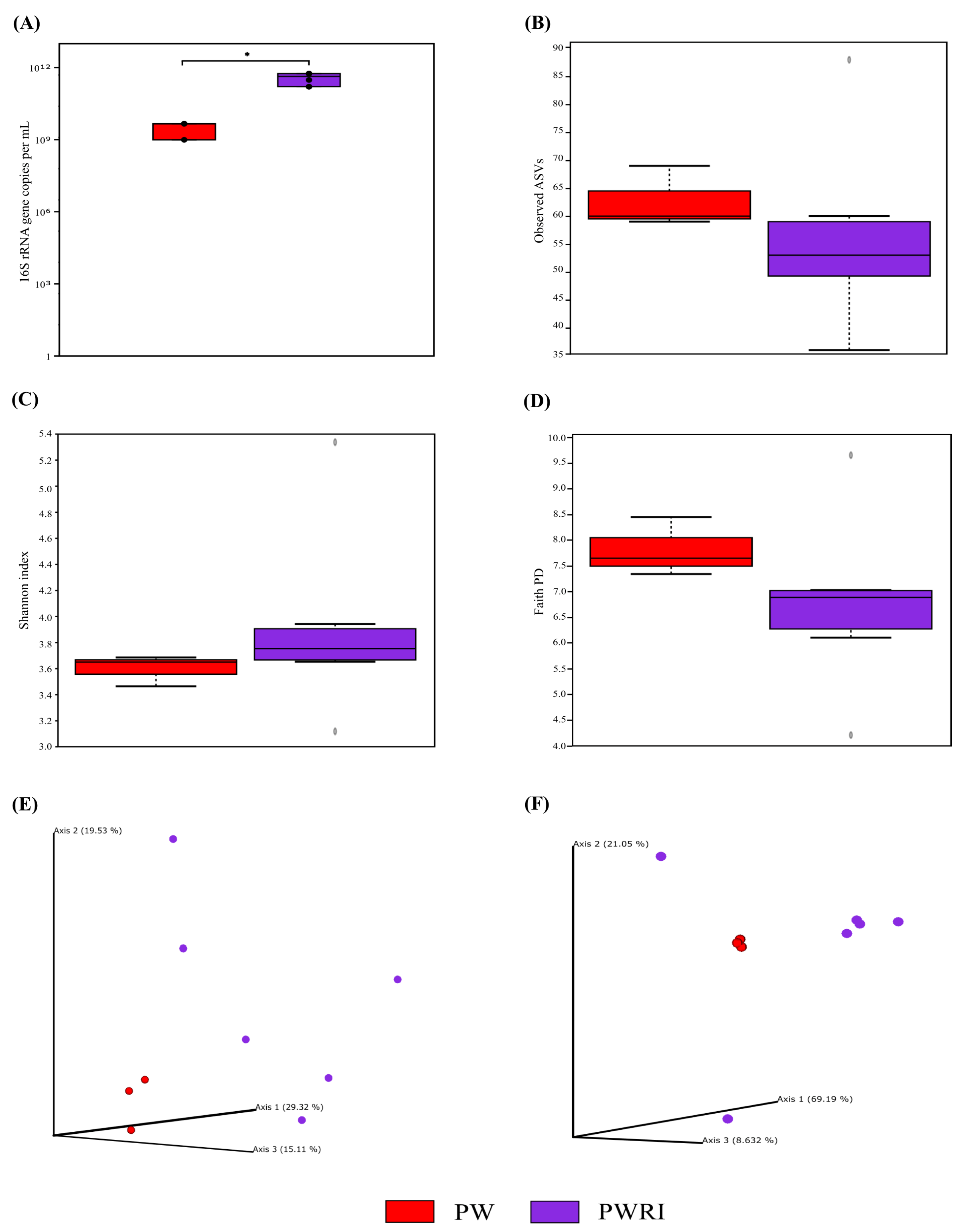

3.3. Total 16S rRNA Abundance and Alpha and Beta Diversity Analyses of the Prokaryotic Communities Present in the PW and PWRI Samples

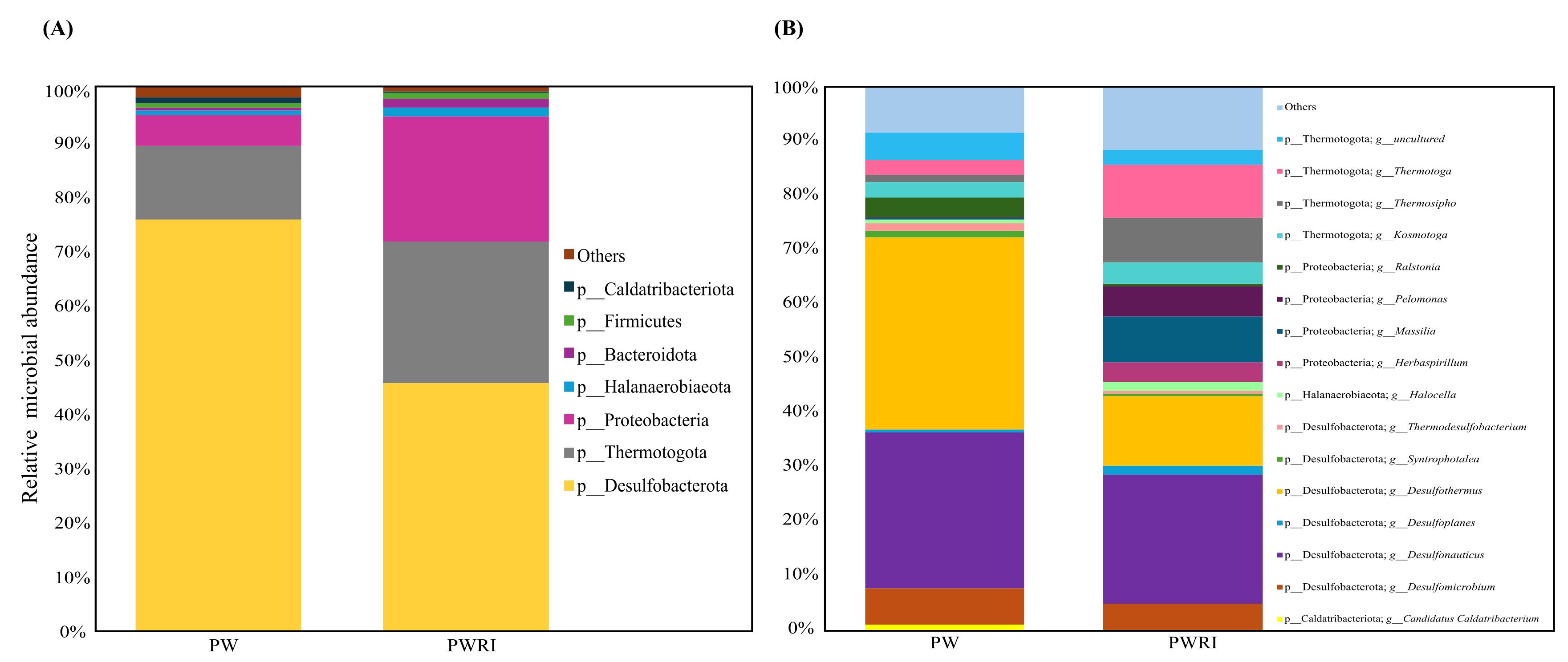

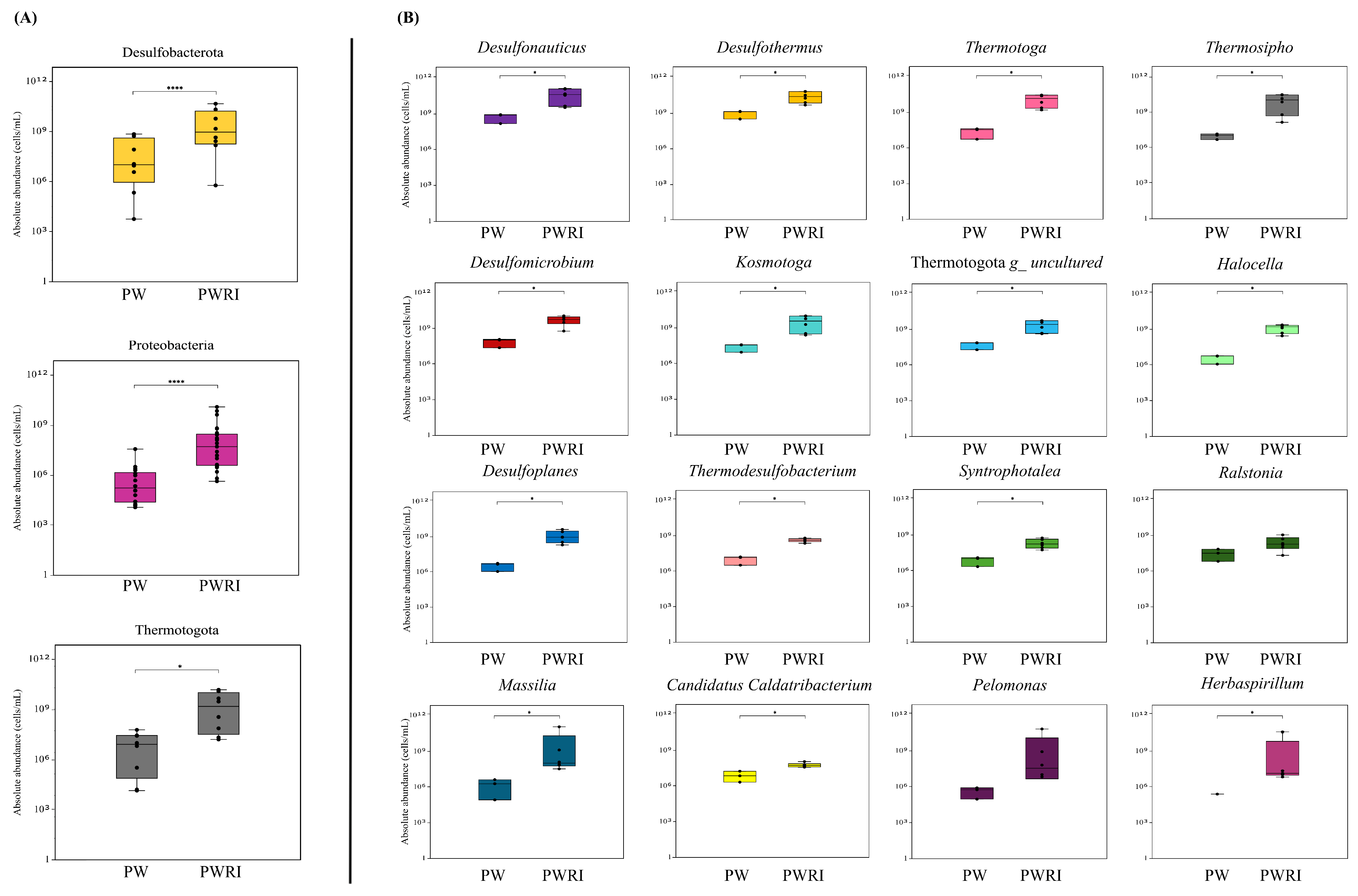

3.4. Microbiome Composition in PW and PWRI Samples

4. Discussion

4.1. Biogenic Sulfide Production Dynamics

4.2. Total 16S rRNA Abundance in Produced Water Systems, Abundance of Planktonic SRB and TAHB, and Sulfide Correlation

4.3. Diversity, Composition, and Effects of Flotation Treatment on the Prokaryotic Communities of PW and PWRI Samples

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IH | Injection header |

| PW | Produced water |

| PWRI | Produced water reinjection |

| SRB | Sulfate-reducing bacteria |

| TAHB | Total anaerobic heterotrophic bacteria |

| H2S | Hydrogen sulfide |

| MPN | Most probable number |

| qPCR | Quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| ASV | Amplicon sequence variant |

| PCoA | Principal coordinate analysis |

| PD | Phylogenetic diversity |

| SPB | Sulfide-producing bacteria |

| THPS | Tetrakis hydroxymethyl phosphonium sulfate |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| 16S rRNA | 16S ribosomal RNA |

References

- Neves Junior, A.; Queiroz, G.N.; Godoy, M.G.; Cardoso, V.S.; Cedrola, S.M.L.; Mansoldo, F.R.P.; Firpo, R.M.; Paiva, L.M.G.; Sohrabi, M.; Vermelho, A.B. Assessing EOR Strategies for Application in Brazilian Pre-Salt Reservoirs. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 223, 211508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Liu, Q.; Lv, J.; Peng, B. Review on Microbial Enhanced Oil Recovery: Mechanisms, Modeling and Field Trials. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 192, 107350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodi, A.; Hosseinzadehsadati, S.B.; Kermani, H.M.; Nick, H.M. On the Benefits of Desulfated Seawater Flooding in Mature Hydrocarbon Fields. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 166732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mokheimer, E.M.A.; Hamdy, M.; Abubakar, Z.; Shakeel, M.R.; Habib, M.A.; Mahmoud, M. A Comprehensive Review of Thermal Enhanced Oil Recovery: Techniques Evaluation. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2019, 141, 030801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muggeridge, A.; Cockin, A.; Webb, K.; Frampton, H.; Collins, I.; Moulds, T.; Salino, P. Recovery Rates, Enhanced Oil Recovery and Technological Limits. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2014, 372, 20120320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udoh, T.H. Improved Insight on the Application of Nanoparticles in Enhanced Oil Recovery Process. Sci. Afr. 2021, 13, e00873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghouti, M.A.; Al-Kaabi, M.A.; Ashfaq, M.Y.; Da’na, D.A. Produced Water Characteristics, Treatment and Reuse: A Review. J. Water Process Eng. 2019, 28, 222–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neff, J.; Lee, K.; DeBlois, E.M. Produced Water: Overview of Composition, Fates, and Effects. In Produced Water; Lee, K., Neff, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohia, N.P.; Onwudiwe, E.C.; Nwanwe, O.I.; Ekwueme, S. A Comparative Study on the Performance of Different Secondary Recovery Techniques for Effective Production from Oil Rim Reservoirs. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2023, 16, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccioli, M.; Aanesen, S.V.; Zhao, H.; Dudek, M.; Øye, G. Gas Flotation of Petroleum Produced Water: A Review on Status, Fundamental Aspects, and Perspectives. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 15579–15592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saththasivam, J.; Loganathan, K.; Sarp, S. An Overview of Oil–Water Separation Using Gas Flotation Systems. Chemosphere 2016, 144, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultanova, A.V.; Mammadov, R.M. About Impact of Clogging Phenomena on Well Productivity. Nafta-Gaz 2023, 79, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lü, Y.; Song, C.; Zhang, D.; Rong, F.; He, L. Separation of Emulsified Crude Oil from Produced Water by Gas Flotation: A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 845, 157304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetere, A.; Profrock, D.; Schrader, W. Qualitative and Quantitative Evaluation of Sulfur-Containing Compound Types in Heavy Crude Oil and Its Fractions. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 8723–8732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigneron, A.; Alsop, E.B.; Lomans, B.P.; Kyrpides, N.C.; Head, I.M.; Tsesmetzis, N. Succession in the Petroleum Reservoir Microbiome through an Oil Field Production Lifecycle. ISME J. 2017, 11, 2141–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basafa, M.; Hawboldt, K. Reservoir Souring: Sulfur Chemistry in Offshore Oil and Gas Reservoir Fluids. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2019, 9, 1105–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Fan, K. Sulfur-Oxidizing Bacteria (SOB) and Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria (SRB) in Oil Reservoir and Biological Control of SRB: A Review. Arch. Microbiol. 2023, 205, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieg, L.M.; Jack, T.R.; Foght, J.M. Biological Souring and Mitigation in Oil Reservoirs. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 92, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, R.W. Global Oil & Gas Depletion: An Overview. Energy Policy 2002, 30, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbadamosi, A.; Patil, S.; Al Shehri, D.; Kamal, M.S.; Hussain, S.S.; Al-Shalabi, E.W.; Hassan, A.M. Recent Advances on the Application of Low Salinity Waterflooding and Chemical Enhanced Oil Recovery. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 9969–9996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannekens, M.; Kroll, L.; Müller, H.; Mbow, F.T.; Meckenstock, R.U. Oil Reservoirs, an Exceptional Habitat for Microorganisms. New Biotechnol. 2019, 49, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, X.; Yu, L.; Huang, L.; Xiu, J.; Lin, W.; Zhang, Y. Characterizing the Microbiome in Petroleum Reservoir Flooded by Different Water Sources. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 653, 872–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurelevicius, D.; Ramos, L.; Abreu, F.; Lins, U.; de Sousa, M.P.; dos Santos, V.V.; Penna, M.; Seldin, L. Long-Term Souring Treatment Using Nitrate and Biocides in High-Temperature Oil Reservoirs. Fuel 2021, 288, 119731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Public Health Association. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 21st ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA; American Water Works Association: Washington, DC, USA; Water Environment Federation: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Petrobras. PE-2P&D-01590-A—Preparation of Modified Postgate “E” Culture Media for Mesophilic Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria (M-SRB). 2017. Available online: https://bit.ly/3J1uNbk (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Petrobras. PE-2P&D-01598—Total Anaerobic Heterotrophic Bacteria (BANHT) Count. 2019. Available online: https://bit.ly/3F4YYgI (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Sakamoto, I.K.; Maintinguer, S.I.; Hirasawa, J.S.; Adorno, M.A.T.; Varesche, M.B.A. Evaluation of Microorganisms with Sulfidogenic Metabolic Potential under Anaerobic Conditions. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2012, 55, 779–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muyzer, G.; De Waal, E.C.; Uitterlinden, A.G. Profiling of Complex Microbial Populations by Denaturing Gradient Gel Electrophoresis Analysis of Polymerase Chain Reaction-Amplified Genes Coding for 16S rRNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1993, 59, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundberg, C.; Al-Soud, W.A.; Larsson, M.; Alm, E.; Yekta, S.S.; Svensson, B.H.; Sørensen, S.J.; Karlsson, A. 454 Pyrosequencing Analyses of Bacterial and Archaeal Richness in 21 Full-Scale Biogas Digesters. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2013, 85, 612–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; Alexander, H.; Alm, E.J.; Arumugam, M.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Reproducible, Interactive, Scalable, and Extensible Microbiome Data Science Using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857, Erratum in Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, A.; McDonald, D.; Navas-Molina, J.A.; Kopylova, E.; Morton, J.T.; Xu, Z.Z.; Kightley, E.P.; Thompson, L.R.; Hyde, E.R.; Gonzalez, A.; et al. Deblur Rapidly Resolves Single-Nucleotide Community Sequence Patterns. mSystems 2017, 2, e00191-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruesse, E.; Quast, C.; Knittel, K.; Fuchs, B.M.; Ludwig, W.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. SILVA: A Comprehensive Online Resource for Quality-Checked and Aligned Ribosomal RNA Sequence Data Compatible with ARB. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 7188–7196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, C.E.; Weaver, W. The Mathematical Theory of Communication; University of Illinois Press: Urbana, IL, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Faith, D.P.; Baker, A.M. Phylogenetic Diversity (PD) and Biodiversity Conservation: Some Bioinformatics Challenges. Evol. Bioinform. Online 2007, 2, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.J. Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance (PERMANOVA). In Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online; Balakrishnan, N., Colton, T., Everitt, B., Piegorsch, W., Ruggeri, F., Teugels, J.L., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, J.T.; Marotz, C.; Washburne, A.; Silverman, J.; Zaramela, L.S.; Edlund, A.; Zengler, K.; Knight, R. Establishing Microbial Composition Measurement Standards with Reference Frames. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, C.; Luukkonen, P.; Yki-Järvinen, H.; Salonen, A.; Korpela, K. Quantitative PCR Provides a Simple and Accessible Method for Quantitative Microbiota Profiling. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkan, H.; Kögler, F.; Namazova, G.; Hatscher, S.; Jelinek, W.; Amro, M. Assessment of the Biogenic Souring in Oil Reservoirs under Secondary and Tertiary Oil Recovery. Energies 2024, 17, 2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushkevych, I.; Dordević, D.; Vítězová, M.; Rittmann, S.K.M. Environmental Impact of Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria, Their Role in Intestinal Bowel Diseases, and Possible Control by Bacteriophages. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedoya, K.; Niño, J.; Acero, J.; Cabarcas, F.; Alzate, J.F. Assessment of the Microbial Community and Biocide Resistance Profile in Production and Injection Waters from an Andean Oil Reservoir in Colombia. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2021, 157, 105137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korenblum, E.; Valoni, É.; Penna, M.; Seldin, L. Bacterial Diversity in Water Injection Systems of Brazilian Offshore Oil Platforms. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 85, 791–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Oliveira, D.A.; Holsten, L.; Steinhauer, K.; de Rezende, J.R. Long-Term Biocide Efficacy and Its Effect on a Souring Microbial Community. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 87, e00842-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Hubbard, C.G.; Zheng, L.; Arora, B.; Li, L.; Karaoz, U.; Ajo-Franklin, J.; Bouskill, N.J. Next Generation Modeling of Microbial Souring–Parameterization through Genomic Information. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2018, 126, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, B.; Laycock, P.J.; Fielder, M. Oilfield Reservoir Souring. In Corrosion; U.S. Department of Energy Office of Scientific and Technical Information: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, I.B.D.; Cintra, L.C. Treatment of Water for Injection into Oil Reservoirs: Evaluation of the Technologies Used. Bachelor’s Thesis, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hagar, H.S.; Foroozesh, J.; Kumar, S.; Zivar, D.; Banan, N.; Dzulkarnain, I. Microbial H2S Generation in Hydrocarbon Reservoirs: Analysis of Mechanisms and Recent Remediation Technologies. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2022, 106, 104729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, R.; Zhao, J.; Li, G.; Min, J.; Han, S.; Zhang, Y. Characterization and Inhibition of Hydrogen Sulfide-Producing Bacteria from Petroleum Reservoirs Subjected to Alkali-Surfactant-Polymer Flooding. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 418, 131961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbow, F.T.; Akbari, A.; Dopffel, N.; Schneider, K.; Mukherjee, S.; Meckenstock, R.U. Insights into the Effects of Anthropogenic Activities on Oil Reservoir Microbiome and Metabolic Potential. New Biotechnol. 2024, 79, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseininoosheri, P.; Lashgari, H.; Sepehrnoori, K. Numerical Prediction of Reservoir Souring under the Effect of Temperature, pH, and Salinity on the Kinetics of Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria. In Proceedings of the SPE International Conference on Oilfield Chemistry, Montgomery, TX, USA, 3–5 April 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okabe, S.; Itoh, T.; Satoh, H.; Watanabe, Y. Analyses of spatial distributions of sulfate-reducing bacteria and their activity in aerobic wastewater biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 5107–5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villahermosa, D.; Corzo, A.; Garcia-Robledo, E.; Gonzalez, J.M.; Papaspyrou, S. Kinetics of indigenous nitrate reducing sulfide oxidizing activity in microaerophilic wastewater biofilms. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0149096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senthilmurugan, B.; Radhakrishnan, J.S.; Poulsen, M.; Tang, L.; AlSaber, S. Assessment of Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion in Oilfield Water Handling Systems Using Molecular Microbiology Methods. Upstream Oil Gas Technol. 2021, 7, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.Y.; Modi, H.; Ayala, A.; Kilbane, J.J. Technical Note: Rapid Detection and Quantification of Microbes Related to Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion Using Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction. Corrosion 2006, 62, 950–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, H.F.; Williams, N.H.; Ogram, A. Phylogeny of Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2000, 31, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leu, J.Y.; McGovern-Traa, C.P.; Porter, A.J.R.; Hamilton, W.A. The Same Species of Sulphate-Reducing Desulfomicrobium Occur in Different Oil Field Environments in the North Sea. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1999, 29, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunoura, T.; Oida, H.; Miyazaki, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Takai, K.; Horikoshi, K. Desulfothermus okinawensis sp. nov., a Thermophilic and Heterotrophic Sulfate-Reducing Bacterium Isolated from a Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Field. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 2360–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, D.S.; Semenova, E.M.; Grouzdev, D.S.; Bidzhieva, S.K.; Babich, T.L.; Loiko, N.G.; Ershov, A.P.; Kadnikov, V.V.; Beletsky, A.V.; Mardanov, A.V.; et al. Sulfidogenic Microbial Communities of the Uzen High-Temperature Oil Field in Kazakhstan. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuever, J.; Rainey, F.A.; Widdel, F. Genus III. Desulfothermus gen. nov. In Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, 2nd ed.; Brenner, D.J., Krieg, N.R., Staley, J.T., Garrity, G.M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005; Volume 2, pp. 955–956. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, A.A. Evolution and Adaptation to Temperature in Thermotogota. Doctoral Dissertation, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ravot, G.; Ollivier, B.; Patel, B.K.; Magot, M.; Garcia, J.L. Emended Description of Thermosipho africanus as a Carbohydrate-Fermenting Species Using Thiosulfate as an Electron Acceptor. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1996, 46, 321–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, K.J.; Sierra-Garcia, I.N.; Zafra, G.; de Oliveira, V.M. Genome-resolved meta-analysis of the microbiome in oil reservoirs worldwide. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, E.T.; Caceres-Martinez, L.E.; Kilaz, G.; Solomon, K.V. Top-Down Enrichment of Oil Field Microbiomes to Limit Souring and Control Oil Composition during Extraction Operations. AIChE J. 2022, 68, e17927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Xue, S.; Ma, Y. Comparative Analysis of Bacterial Community and Functional Species in Oil Reservoirs with Different in Situ Temperatures. Int. Microbiol. 2020, 23, 557–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voskuhl, L. Unraveling Mechanisms of Microbial Community Assembly Using Naturally Replicated Microbiomes. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität Duisburg–Essen, Duisburg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Coon, G.R.; Williams, L.C.; Matthews, A.; Diaz, R.; Kevorkian, R.T.; LaRowe, D.E.; Lloyd, K.G. Control of hydrogen concentrations by microbial sulfate reduction in two contrasting anoxic coastal sediments. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1455857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, H.; Xiong, S.; Gao, G.; Song, Y.; Cao, G.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, X. Bacteria in the Injection Water Differently Impacts the Bacterial Communities of Production Wells in High-Temperature Petroleum Reservoirs. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, J.L.; Andrews, R.S.; Akob, D.M.; DeVera, C.A.; Mumford, A.; McCray, J.E.; McIntosh, J.C. Microbial Community Composition of a Hydrocarbon Reservoir 40 Years after a CO2 Enhanced Oil Recovery Flood. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2018, 94, fiy153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, B.C.; Gong, S.; Greenfield, P.; Midgley, D.J.; Paulsen, I.T.; George, S.C. Aromatic Compound-Degrading Taxa in an Anoxic Coal Seam Microbiome from the Surat Basin, Australia. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2021, 97, fiab053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughlin, R.B., Jr.; Neff, J.M. Influence of Temperature, Salinity, and Phenanthrene (a Petroleum Derived Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon) on the Respiration of Larval Mud Crabs, Rhithropanopeus harrisii. Estuar. Coast. Mar. Sci. 1980, 10, 655–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, M.; Kim, D.U.; Ka, J.O. Massilia aromaticivorans sp. nov., a BTEX-Degrading Bacterium Isolated from Arctic Soil. Curr. Microbiol. 2021, 78, 2143–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lou, J.; Gu, H.; Luo, X.; Yang, L.; Wu, L.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Xu, J. Efficient Biodegradation of Phenanthrene by a Novel Strain Massilia sp. WF1 Isolated from a PAH-Contaminated Soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 13378–13388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.X.; Wu, H.Y.; Qiu, Y.P.; Shi, X.Q.; He, G.H.; Zhang, J.F.; Wu, J.C. Degradation of Fluoranthene by a Newly Isolated Strain of Herbaspirillum chlorophenolicum from Activated Sludge. Biodegradation 2011, 22, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Shi, X.; Wu, J. Biodegradation of Pyrene by Free and Immobilized Cells of Herbaspirillum chlorophenolicum Strain FA1. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2016, 227, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Domingues, V.d.S.P.; Sousa, M.P.d.; Waldow, V.; Akamine, R.; Seldin, L.; Jurelevicius, D. Sulfide Production and Microbial Dynamics in the Water Reinjection System from an Offshore Oil-Producing Platform. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010038

Domingues VdSP, Sousa MPd, Waldow V, Akamine R, Seldin L, Jurelevicius D. Sulfide Production and Microbial Dynamics in the Water Reinjection System from an Offshore Oil-Producing Platform. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010038

Chicago/Turabian StyleDomingues, Vitória da Silva Pereira, Maira Paula de Sousa, Vinicius Waldow, Rubens Akamine, Lucy Seldin, and Diogo Jurelevicius. 2026. "Sulfide Production and Microbial Dynamics in the Water Reinjection System from an Offshore Oil-Producing Platform" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010038

APA StyleDomingues, V. d. S. P., Sousa, M. P. d., Waldow, V., Akamine, R., Seldin, L., & Jurelevicius, D. (2026). Sulfide Production and Microbial Dynamics in the Water Reinjection System from an Offshore Oil-Producing Platform. Microorganisms, 14(1), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010038