Novel Genetic Diversity and Geographic Structures of Aspergillus fumigatus (Order Eurotiales, Family Aspergillaceae) in the Karst Regions of Guizhou, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

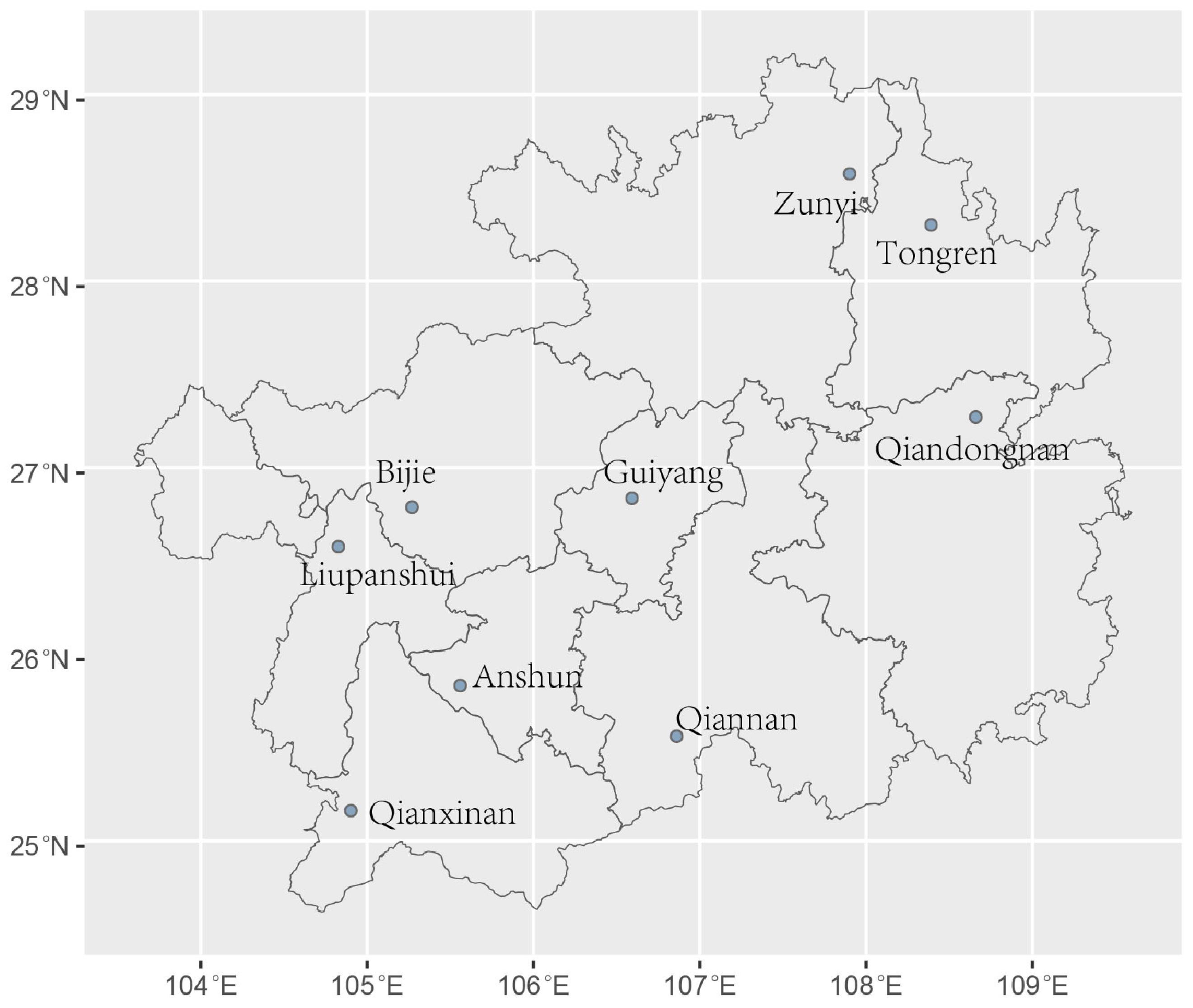

2.1. Soil Samples, A. fumigatus Isolation and Identification

2.2. STR Genotypes and Population Genetic Analyses

2.3. Susceptibility of A. fumigatus Isolates and cyp51A Gene Sequencing

3. Results

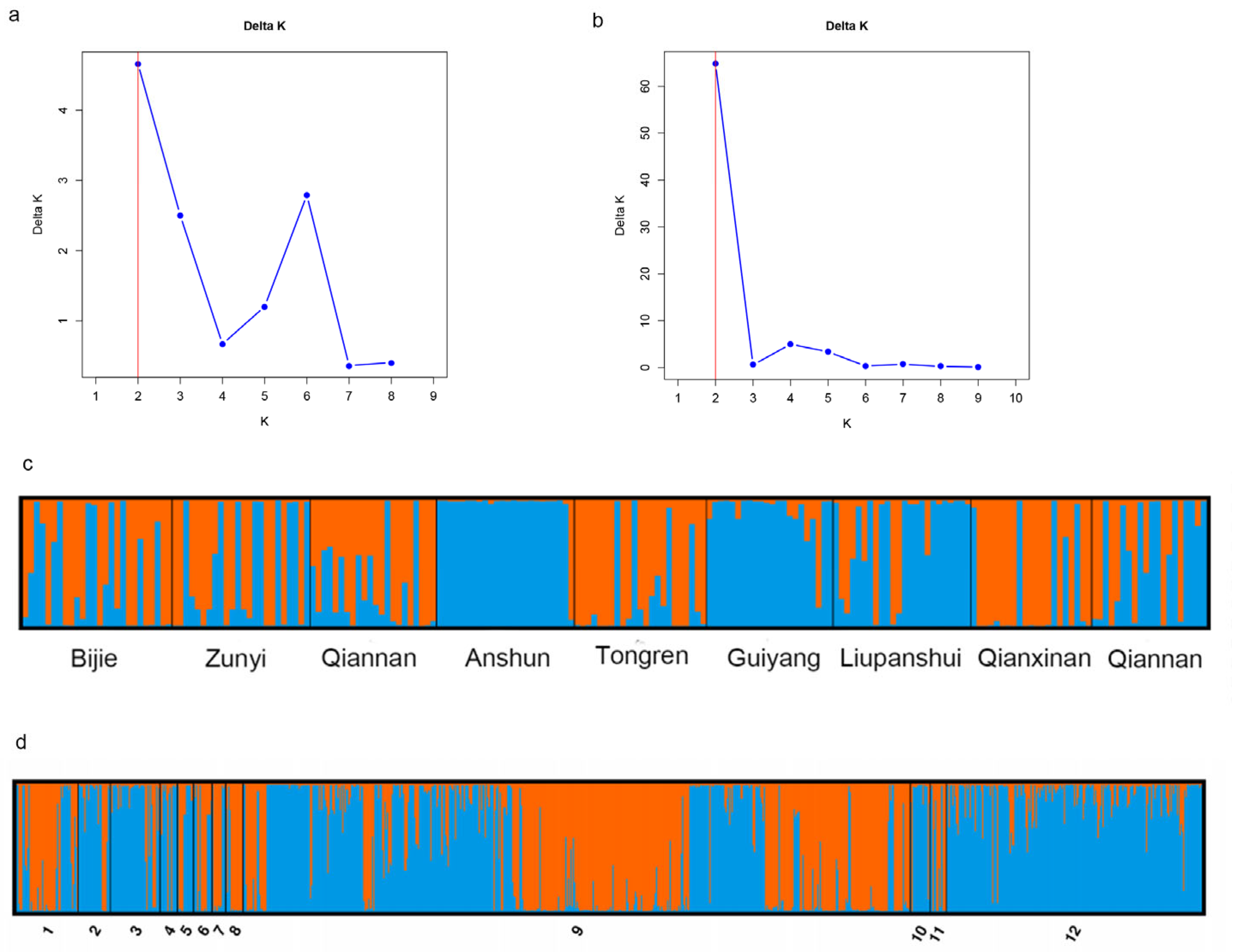

3.1. Genotyping of A. fumigatus Samples from Guizhou Province

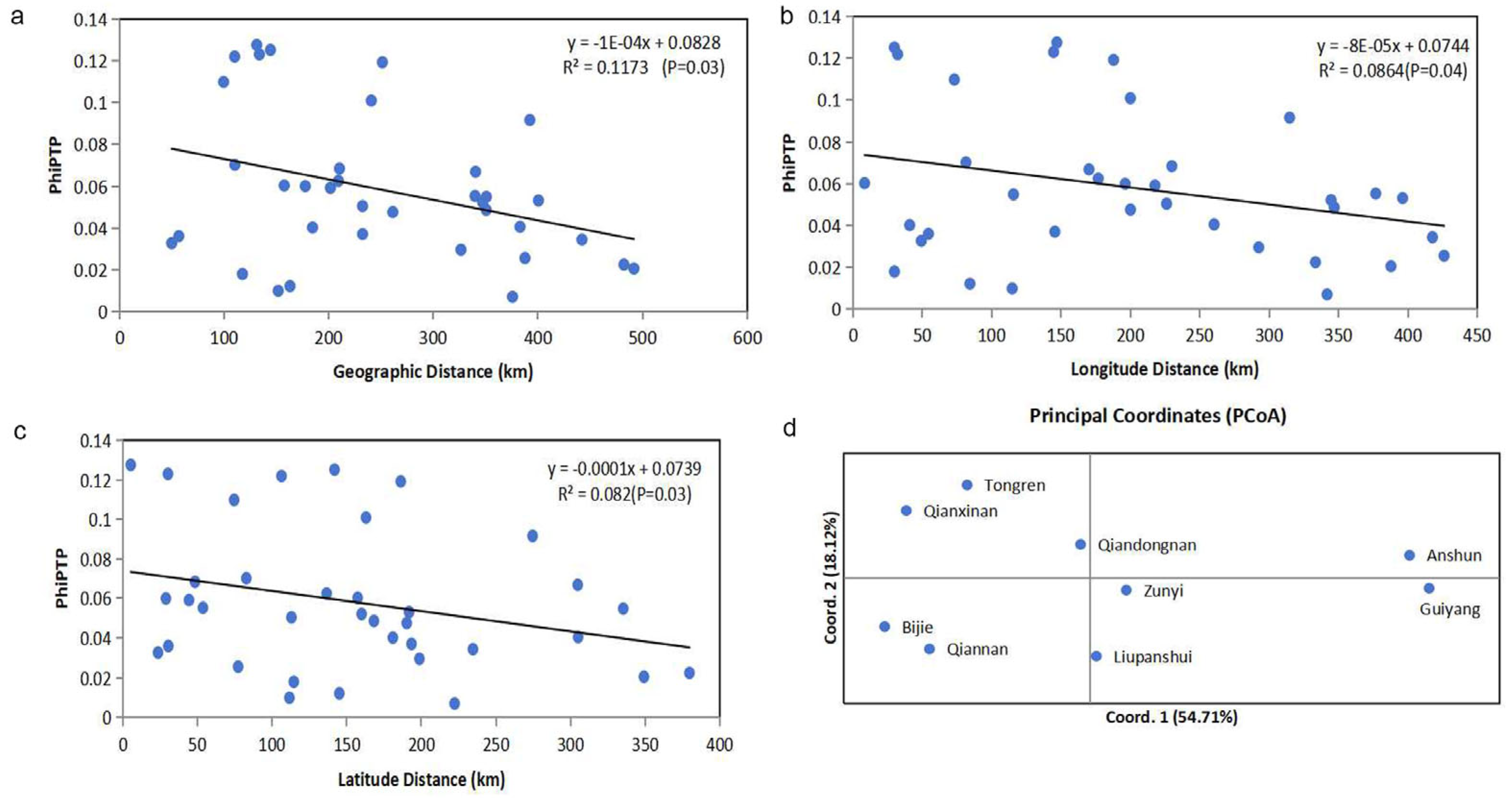

3.2. Relationships Among Local Populations

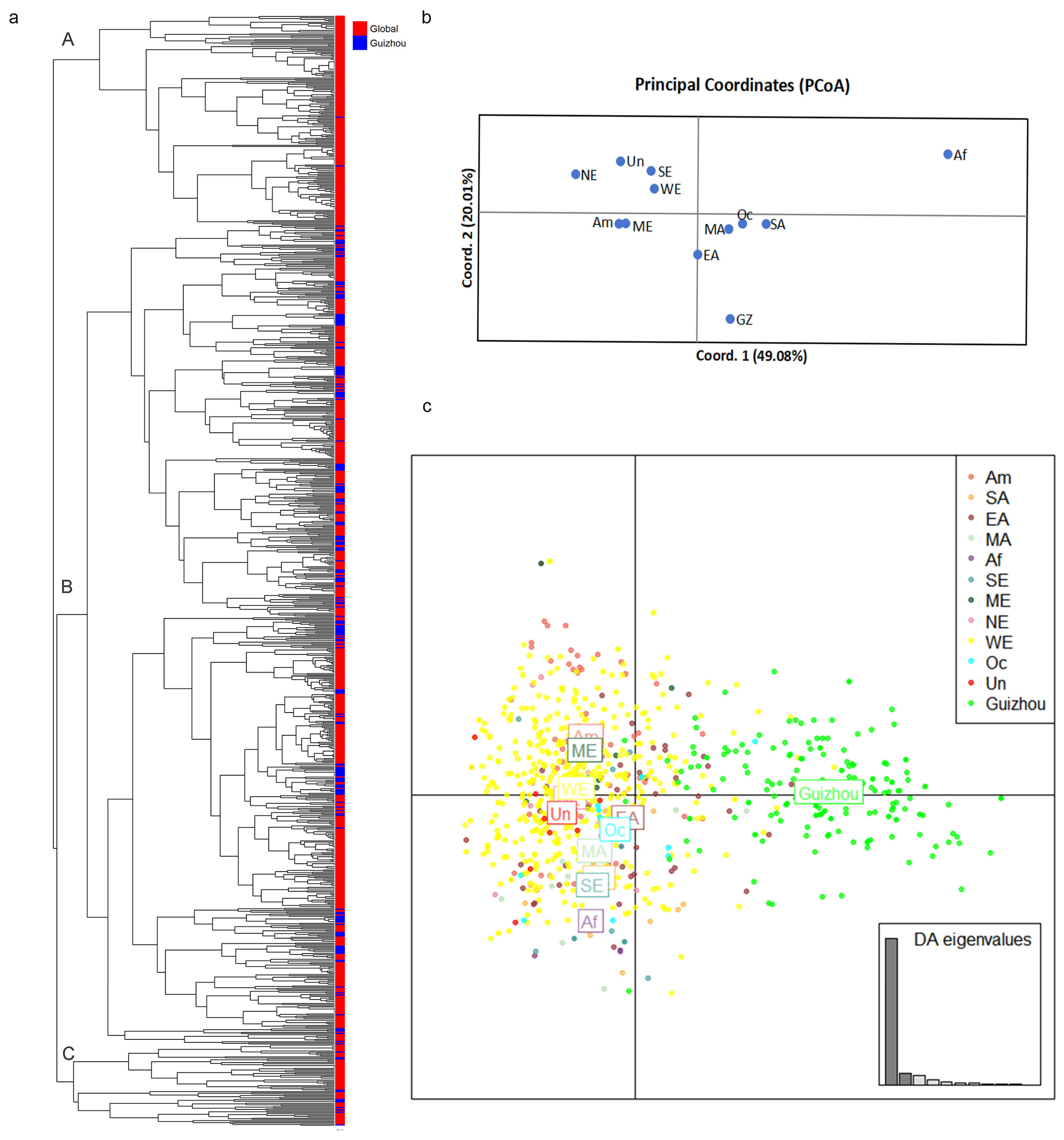

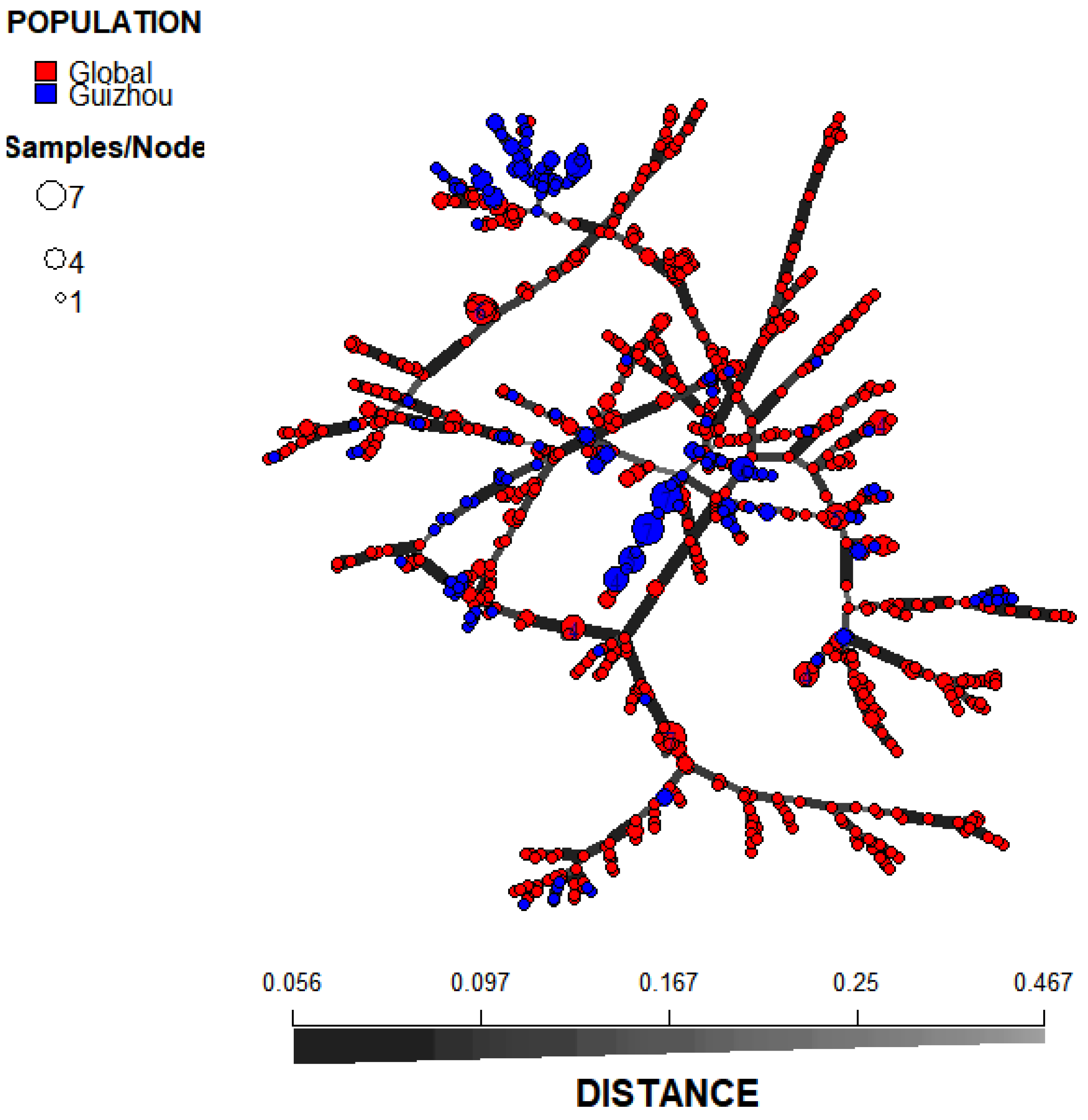

3.3. Relationship Between the Guizhou Population of A. fumigatus and Those in Other Global Regions

3.4. Prevalence of Azole Resistance and cyp51A Mutation

4. Discussion

4.1. Extensive Novel Genetic Diversity in Guizhou Province

4.2. High Level of Genetic Differentiation Among the Nine Geographical Populations

4.3. Low Level of Azole Resistance

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| STRs | Short Tandem Repeats |

| ARAF | azole-resistant A. fumigatus |

| ITR | itraconazole |

| VOR | voriconazole |

| MIC | minimum inhibitory concentration |

References

- Latgé, J.-P.; Chamilos, G. Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillosis in 2019. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 33, e00140-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doughty, K.J.; Sierotzki, H.; Semar, M.; Goertz, A. Selection and Amplification of Fungicide Resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus in Relation to DMI Fungicide Use in Agronomic Settings: Hotspots versus Coldspots. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Huang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y. Unveiling environmental transmission risks: Comparative analysis of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus clinical and environmental isolates from Yunnan, China. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e01594-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordana, N.; Johnson, A.; Quinn, K.; Obar, J.J.; Cramer, R.A. Recent developments in Aspergillus fumigatus research: Diversity, drugs, and disease. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2025, 89, e00011-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyedmousavi, S.; Guillot, J.; Arné, P.; de Hoog, G.S.; Mouton, J.W.; Melchers, W.J.G.; Verweij, P.E. Aspergillus and aspergilloses in wild and domestic animals: A global health concern with parallels to human disease. Med. Mycol. 2015, 53, 765–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, B.H.; Romani, L.R. Invasive aspergillosis in chronic granulomatous disease. Med. Mycol. 2009, 47, S282–S290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, K.; Strek, M.E. Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2010, 7, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashu, E.E.; Hagen, F.; Chowdhary, A.; Meis, J.F.; Xu, J. Global Population Genetic Analysis of Aspergillus fumigatus. mSphere 2017, 2, e00019-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Linden, J.W.M.; Snelders, E.; Kampinga, G.A.; Rijnders, B.J.A.; Mattsson, E.; Debets-Ossenkopp, Y.J.; Kuijper, E.J.; Van Tiel, F.H.; Melchers, W.J.G.; Verweij, P.E. Clinical Implications of Azole Resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus, the Netherlands, 2007–2009. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 1846–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroczyńska, M.; Kurzyk, E.; Śliwka-Kaszyńska, M.; Nawrot, U.; Adamik, M.; Brillowska-Dąbrowska, A. The Effect of Posaconazole, Itraconazole and Voriconazole in the Culture Medium on Aspergillus fumigatus Triazole Resistance. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, D.W.; Radford, S.A.; Oakley, K.L.; Hall, L.; Johnson, E.M.; Warnock, D.W. Correlation between in-vitro susceptibility testing to itraconazole and in-vivo outcome of Aspergillus fumigatus infection. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1997, 40, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Paassen, J.; Russcher, A.; Veld-van Wingerden, A.W.M.; Verweij, P.E.; Kuijper, E.J. Emerging aspergillosis by azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus at an intensive care unit in the Netherlands, 2010 to 2013. Eurosurveillance 2016, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, C.O.; Kim, H.Y.; Duong, T.-M.N.; Moran, E.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Denning, D.W.; Perfect, J.R.; Nucci, M.; Chakrabarti, A.; Rickerts, V.; et al. Aspergillus fumigatus—A systematic review to inform the World Health Organization priority list of fungal pathogens. Med. Mycol. 2024, 62, myad129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Zhu, G.; Lin, H.; Guo, J.; Deng, S.; Wu, W.; Goldman, G.H.; Lu, L.; Zhang, Y. Variability in competitive fitness among environmental and clinical azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus isolates. mBio 2024, 15, e00263-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, N.P.; Verweij, P.E. Aspergillus fumigatus and pan-azole resistance: Who should be concerned? Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 33, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Han, L.; Gong, J.; Liu, L.; Miao, B.; Xu, J. Research advances and public health strategies in China on WHO priority fungal pathogens. Mycology 2025, 16, 1437–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korfanty, G.A.; Dixon, M.; Jia, H.; Yoell, H.; Xu, J. Genetic Diversity and Dispersal of Aspergillus fumigatus in Arctic Soils. Genes 2021, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuypers, L.; Aerts, R.; Van de gaer, O.; Vinken, L.; Merckx, R.; Gerils, V.; Vande Velde, G.; Reséndiz-Sharpe, A.; Maertens, J.; Lagrou, K. Doubling of triazole resistance rates in invasive aspergillosis over a 10-year period, Belgium, 1 April 2022 to 31 March 2023. Eurosurveillance 2025, 30, 2400559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verweij, P.E.; Arendrup, M.C.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Gold, J.A.W.; Lockhart, S.R.; Chiller, T.; White, P.L. Dual use of antifungals in medicine and agriculture: How do we help prevent resistance developing in human pathogens? Drug Resist. Updates 2022, 65, 100885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Castlebury, L.A.; Miller, A.N.; Huhndorf, S.M.; Schoch, C.L.; Seifert, K.A.; Rossman, A.Y.; Rogers, J.D.; Kohlmeyer, J.; Volkmann-Kohlmeyer, B. An overview of the systematics of the Sordariomycetes based on a four-gene phylogeny. Mycologia 2006, 98, 1076–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Xiao, F.; Wu, H.; Mo, S.; Zhu, S.; Yu, L.; Xiong, K.; Lan, A. Combating the Fragile Karst Environment in Guizhou, China. AMBIO J. Hum. Environ. 2006, 35, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, S.; Xiong, K.; Li, B.; Tian, Z.; Chen, Q.; Yan, L.; Xiao, S. The spatial distribution and factors affecting karst cave development in Guizhou Province. J. Geogr. Sci. 2017, 27, 1011–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Luo, J.; Niu, S.; Bai, D.; Chen, Y. Population structure analysis to explore genetic diversity and geographical distribution characteristics of wild tea plant in Guizhou Plateau. BMC Plant Biol. 2023, 23, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zhang, H.; Wei, X.; Qi, Y.; Wang, M.; Sun, J.; Ding, L.; Tang, S.; Qiu, Z.E.; Cao, Y.; et al. Genetic structure and diversity of Oryza sativa L. in Guizhou, China. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2007, 52, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, X.; Lu, J.; Tian, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Qu, L.; et al. Analysis of genetic diversity and genetic structure of indigenous chicken populations in Guizhou province based on genome-wide single nucleotide polymorphism markers. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Z.; Zhi, J.; Zhou, Y.; Meng, Z.; Wen, J. Population genetic structure and migration patterns of Dendrothrips minowai (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in Guizhou, China. Entomol. Sci. 2017, 20, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-F.; Liu, J.-K.; Hyde, K.D.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Ran, H.-Y.; Liu, Z.-Y. Ascomycetes from karst landscapes of Guizhou Province, China. Fungal Divers. 2023, 122, 1–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Valk, H.A.; Meis, J.F.G.M.; Curfs, I.M.; Muehlethaler, K.; Mouton, J.W.; Klaassen, C.H.W. Use of a Novel Panel of Nine Short Tandem Repeats for Exact and High-Resolution Fingerprinting of Aspergillus fumigatus Isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 4112–4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Wang, R.; Li, X.; Peng, B.; Yang, G.; Zhang, K.-Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J. Genetic Diversity and Azole Resistance Among Natural Aspergillus fumigatus Populations in Yunnan, China. Microb. Ecol. 2021, 83, 869–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Korfanty, G.A.; Mo, M.; Wang, R.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Li, S.; Wu, J.-Y.; Zhang, K.-Q.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Extensive Genetic Diversity and Widespread Azole Resistance in Greenhouse Populations of Aspergillus fumigatus in Yunnan, China. mSphere 2021, 6, e00066-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peakall, R.; Smouse, P.E. GenAlEx 6.5: Genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research—An update. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2537–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubisz, M.J.; Falush, D.; Stephens, M.; Pritchard, J.K. Inferring weak population structure with the assistance of sample group information. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2009, 9, 1322–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.; Stephens, M.; Pritchard, J.K. fastSTRUCTURE: Variational Inference of Population Structure in Large SNP Data Sets. Genetics 2014, 197, 573–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.L.; Liu, J.X. StructureSelector: A web-based software to select and visualize the optimal number of clusters using multiple methods. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2017, 18, 176–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jombart, T.; Ahmed, I. adegenet 1.3-1: New tools for the analysis of genome-wide SNP data. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 3070–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Peterson, D.; Filipski, A.; Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 2725–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agapow, P.M.; Burt, A. Indices of multilocus linkage disequilibrium. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2001, 1, 101–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI M38; Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Filamentous Fungi. 3rd ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2017. Available online: https://standards.globalspec.com/std/10266415/clsi-m38 (accessed on 10 January 2024).

- Snelders, E.; Camps, S.M.T.; Karawajczyk, A.; Rijs, A.J.M.M.; Zoll, J.; Verweij, P.E.; Melchers, W.J.G. Genotype–phenotype complexity of the TR46/Y121F/T289A cyp51A azole resistance mechanism in Aspergillus fumigatus. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2015, 82, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Gong, J.; Duan, C.; He, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J. Genetic structure and triazole resistance among Aspergillus fumigatus populations from remote and undeveloped regions in Eastern Himalaya. mSphere 2023, 8, e00071-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashu, E.E.; Korfanty, G.A.; Xu, J. Evidence of unique genetic diversity in Aspergillus fumigatus isolates from Cameroon. Mycoses 2017, 60, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korfanty, G.A.; Teng, L.; Pum, N.; Xu, J. Contemporary Gene Flow is a Major Force Shaping the Aspergillus fumigatus Population in Auckland, New Zealand. Mycopathologia 2019, 184, 479–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashu, E.E.; Kim, G.Y.; Roy-Gayos, P.; Dong, K.; Forsythe, A.; Giglio, V.; Korfanty, G.; Yamamura, D.; Xu, J. Limited evidence of fungicide-driven triazole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in Hamilton, Canada. Can. J. Microbiol. 2018, 64, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; Yuan, C.; Zhang, P.; Wang, H.; Luo, D.; Dai, X. Study on the characteristics of genetic diversity of different populations of Guizhou endemic plant Rhododendron pudingense based on microsatellite markers. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Tu, Y.; Zou, J.; Luo, K.; Ji, G.; Shan, Y.; Ju, X.; Shu, J. Population structure and genetic diversity of seven Chinese indigenous chicken populations in Guizhou Province. J. Poult. Sci. 2021, 58, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Yuan, C.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; He, S.; Chen, M.; Dai, X.; Luo, D. Study on the Diversity Characteristics of the Endemic Plant Rhododendron bailiense in Guizhou, China Based on SNP Molecular Markers. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e70966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Dong, F.; Zhao, J.; Fan, H.; Qin, C.; Li, R.; Verweij, P.E.; Zheng, Y.; Han, L. High azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus isolates from strawberry fields, China, 2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korfanty, G.; Kazerouni, A.; Dixon, M.; Trajkovski, M.; Gomez, P.; Xu, J. What in Earth? Analyses of Canadian soil populations of Aspergillus fumigatus. Can. J. Microbiol. 2024, 71, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, S.F.; Berkow, E.L.; Stevenson, K.L.; Litvintseva, A.P.; Lockhart, S.R. Isolation of azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus from the environment in the south-eastern USA. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 2443–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amona, F.M.; Oladele, R.O.; Resendiz-Sharpe, A.; Denning, D.W.; Kosmidis, C.; Lagrou, K.; Zhong, H.; Han, L. Triazole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus isolates in Africa: A systematic review. Med. Mycol. 2022, 60, myac059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigitano, A.; Esposto, M.C.; Romanò, L.; Auxilia, F.; Tortorano, A.M. Azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in the Italian environment. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2019, 16, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisi, U. Assessment of selection and resistance risk for demethylation inhibitor fungicides in Aspergillus fumigatus in agriculture and medicine: A critical review. Pest Manag. Sci. 2014, 70, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzo-Gallo, P.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Chumbita, M.; Aiello, T.F.; Gallardo-Pizarro, A.; Peyrony, O.; Teijon-Lumbreras, C.; Alcazar-Fuoli, L.; Espasa, M.; Soriano, A. Report of three azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus cases with TR34/L98H mutation in hematological patients in Barcelona, Spain. Infection 2024, 52, 1651–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snelders, E.; van der Lee, H.A.L.; Kuijpers, J.; Rijs, A.J.M.; Varga, J.; Samson, R.A.; Mellado, E.; Donders, A.R.T.; Melchers, W.J.G.; Verweij, P.E. Emergence of azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus and spread of a single resistance mechanism. PLoS Med. 2008, 5, e219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meis, J.F.; Chowdhary, A.; Rhodes, J.L.; Fisher, M.C.; Verweij, P.E. Clinical implications of globally emerging azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20150460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verweij, P.E.; Chowdhary, A.; Melchers, W.J.G.; Meis, J.F.; Weinstein, R.A. Azole Resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: Can We Retain the Clinical Use of Mold-Active Antifungal Azoles? Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Moreno, C.; Lavergne, R.-A.; Hagen, F.; Morio, F.; Meis, J.F.; Le Pape, P. Azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus harboring TR34/L98H, TR46/Y121F/T289A and TR53 mutations related to flower fields in Colombia. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockhart, S.R.; Frade, J.P.; Etienne, K.A.; Pfaller, M.A.; Diekema, D.J.; Balajee, S.A. Azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus isolates from the ARTEMIS global surveillance study is primarily due to the TR/L98H mutation in the cyp51A gene. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 4465–4468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zou, Z.; Gong, Y.; Qu, F.; Bao, Z.; Qiu, G.; Song, M.; Zhang, Q. Epidemiology and molecular characterizations of azole resistance in clinical and environmental Aspergillus fumigatus isolates from China. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 5878–5884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J. Assessing global fungal threats to humans. mLife 2022, 1, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Population | No. of Strains | No. of Genotypes | Microsatellite Loci and Number of Alleles (Private Alleles) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2A | 2B | 2C | 3A | 3B | 3C | 4A | 4B | 4C | Total | |||

| Guiyang | 22 | 20 | 10 | 8 (1) | 10 | 17 (6) | 6 | 7 | 4 | 7 (1) | 4 | 73 (8) |

| Zunyi | 24 | 15 | 8 | 12 (1) | 12 (2) | 10 (2) | 11 (2) | 10 (2) | 7 (1) | 5 | 5 | 80 (10) |

| Qiannan | 22 | 22 | 9 | 6 | 11 | 13 (1) | 9 | 10 (2) | 9 (2) | 5 | 5 (1) | 77 (6) |

| Anshun | 24 | 17 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 15 (3) | 6 | 7 (2) | 5 (1) | 8 | 6 | 69 (6) |

| Qiandongnan | 20 | 19 | 10 | 9 | 9 (1) | 16 (3) | 10 | 10 | 6 (1) | 9 (1) | 6 | 85 (6) |

| Qianxinan | 21 | 14 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 10 (3) | 8 | 11 (1) | 6 | 5 (1) | 3 | 65 (5) |

| Liupanshui | 24 | 17 | 8 | 7 (1) | 10 | 15 | 12 | 11 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 78 (1) |

| Bijie | 26 | 23 | 8 | 9 (1) | 13 (1) | 20 (3) | 11 (1) | 16 (5) | 10 (1) | 4 | 4 | 95 (12) |

| Tongren | 23 | 16 | 6 (1) | 8 | 10 (2) | 11 | 9 | 13 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 75 (3) |

| Total | 206 | 161 | 16 (1) | 18 (4) | 26 (6) | 52 (21) | 23 (3) | 36 (12) | 18 (6) | 13 (3) | 10 (1) | 212 (57) |

| Sampling Site | Effective Alleles (Ne) | Shannon’s Information Index (I) | Diversity (h) | Unbiased Diversity (uh) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bijie | 7.426 | 1.982 | 0.789 | 0.825 |

| Zunyi | 6.543 | 1.963 | 0.822 | 0.88 |

| Qiannan | 5.426 | 1.807 | 0.775 | 0.813 |

| Anshun | 5.132 | 1.679 | 0.732 | 0.778 |

| Tongren | 5.984 | 1.88 | 0.806 | 0.86 |

| Guiyang | 5.695 | 1.711 | 0.731 | 0.769 |

| Liupanshui | 6.068 | 1.85 | 0.785 | 0.834 |

| Qianxinan | 5.414 | 1.741 | 0.771 | 0.83 |

| Qiandongnan | 7.099 | 2.026 | 0.835 | 0.881 |

| Bijie | Zunyi | Qiannan | Anshun | Tongren | Guiyang | Liupanshui | Qianxinan | Qiandongnan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.009 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.013 | 0.003 | 0.001 | Bijie | |

| 0.030 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.009 | 0.006 | 0.264 | 0.078 | 0.158 | Zunyi | |

| 0.062 | 0.055 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 0.001 | Qiannan | |

| 0.122 | 0.041 | 0.123 | 0.001 | 0.204 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | Anshun | |

| 0.049 | 0.036 | 0.067 | 0.092 | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.110 | 0.101 | Tongren | |

| 0.128 | 0.037 | 0.125 | 0.010 | 0.101 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | Guiyang | |

| 0.033 | 0.007 | 0.050 | 0.070 | 0.053 | 0.060 | 0.002 | 0.031 | Liupanshui | |

| 0.040 | 0.022 | 0.059 | 0.110 | 0.021 | 0.119 | 0.060 | 0.015 | Qianxinan | |

| 0.055 | 0.012 | 0.048 | 0.052 | 0.018 | 0.068 | 0.026 | 0.034 | Qiandongnan |

| Locus | No. of Alleles in All 12 Populations | No. of Alleles in Guizhou | Private Alleles in Guizhou (Location, Frequency of Private Allele) |

|---|---|---|---|

| STRAF2A | 19 | 16 | None |

| STRAF2B | 25 | 18 | 6 (Liupanshui, 0.005), 31 (Guiyang, 0.005) |

| STRAF2C | 30 | 26 | 6 (Qiannan, Tongren, Qianxinan, 0.015), 7 (Bijie, Qiannan, Anshun, 0.049), 29 (Bijie, 0.005), 30 (Zunyi, 0.005) |

| STRAF3A | 86 | 52 | 64 (Qianxinan, 0.005), 104 (Bijie, 0.005), 106 (Guiyang, 0.015), 107 (Guiyang, 0.005) |

| STRAF3B | 33 | 23 | None |

| STRAF3C | 49 | 36 | 35 (Anshun, 0.005), 38 (Bijie, 0.005) |

| STRAF4A | 26 | 18 | 3 (Qiannan, Guiyang, Qiandongnan, 0.02) |

| STRAF4B | 25 | 13 | 18 (Qiandongnan, 0.005), 21 (Guiyang, 0.005) |

| STRAF4C | 29 | 10 | None |

| Total | 322 | 212 | 15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhou, D.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J. Novel Genetic Diversity and Geographic Structures of Aspergillus fumigatus (Order Eurotiales, Family Aspergillaceae) in the Karst Regions of Guizhou, China. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010237

Zhou D, Liu Y, Zhang Q, Zhang Y, Xu J. Novel Genetic Diversity and Geographic Structures of Aspergillus fumigatus (Order Eurotiales, Family Aspergillaceae) in the Karst Regions of Guizhou, China. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):237. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010237

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Duanyong, Yixian Liu, Qifeng Zhang, Ying Zhang, and Jianping Xu. 2026. "Novel Genetic Diversity and Geographic Structures of Aspergillus fumigatus (Order Eurotiales, Family Aspergillaceae) in the Karst Regions of Guizhou, China" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010237

APA StyleZhou, D., Liu, Y., Zhang, Q., Zhang, Y., & Xu, J. (2026). Novel Genetic Diversity and Geographic Structures of Aspergillus fumigatus (Order Eurotiales, Family Aspergillaceae) in the Karst Regions of Guizhou, China. Microorganisms, 14(1), 237. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010237