The Restorative Effects of Electron Mediators on the Formation of Electroactive Biofilms in Geobacter sulfurreducens

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains

2.2. Mutants Construction

2.3. BESs Construction and Biofilm Formation

2.4. Biofilm Imaging

2.5. Electrochemical Measurements

2.6. Extraction and Determination of Extracellular Polymeric Substances

2.7. c-Cyts Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

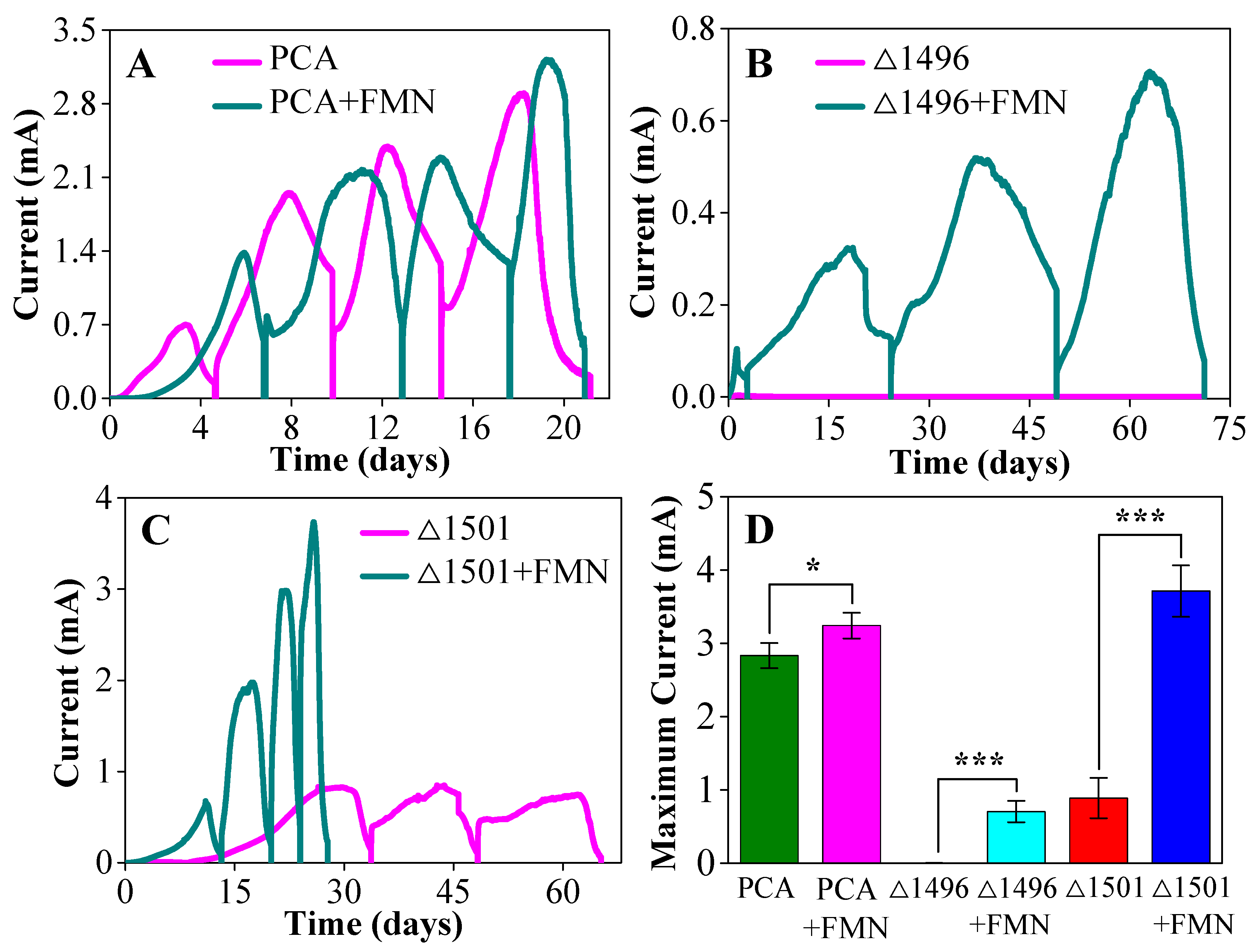

3.1. Exogenous FMN Promoted Biofilm Formation

3.2. Exogenous FMN Increased EET Efficiency

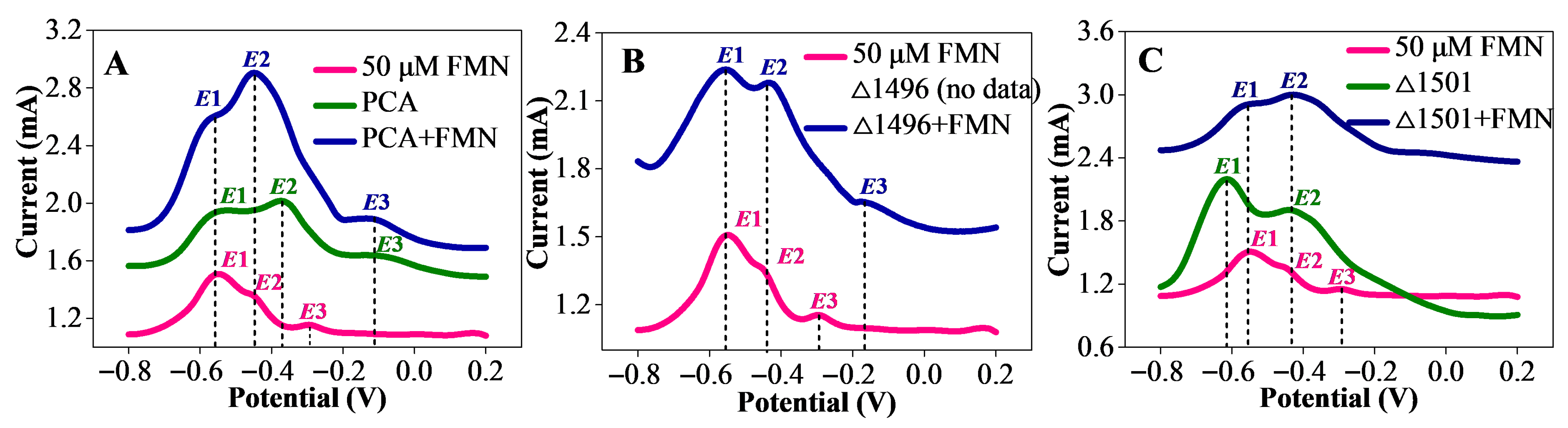

3.3. Exogenous FMN Enhanced Biofilm Electroactivity

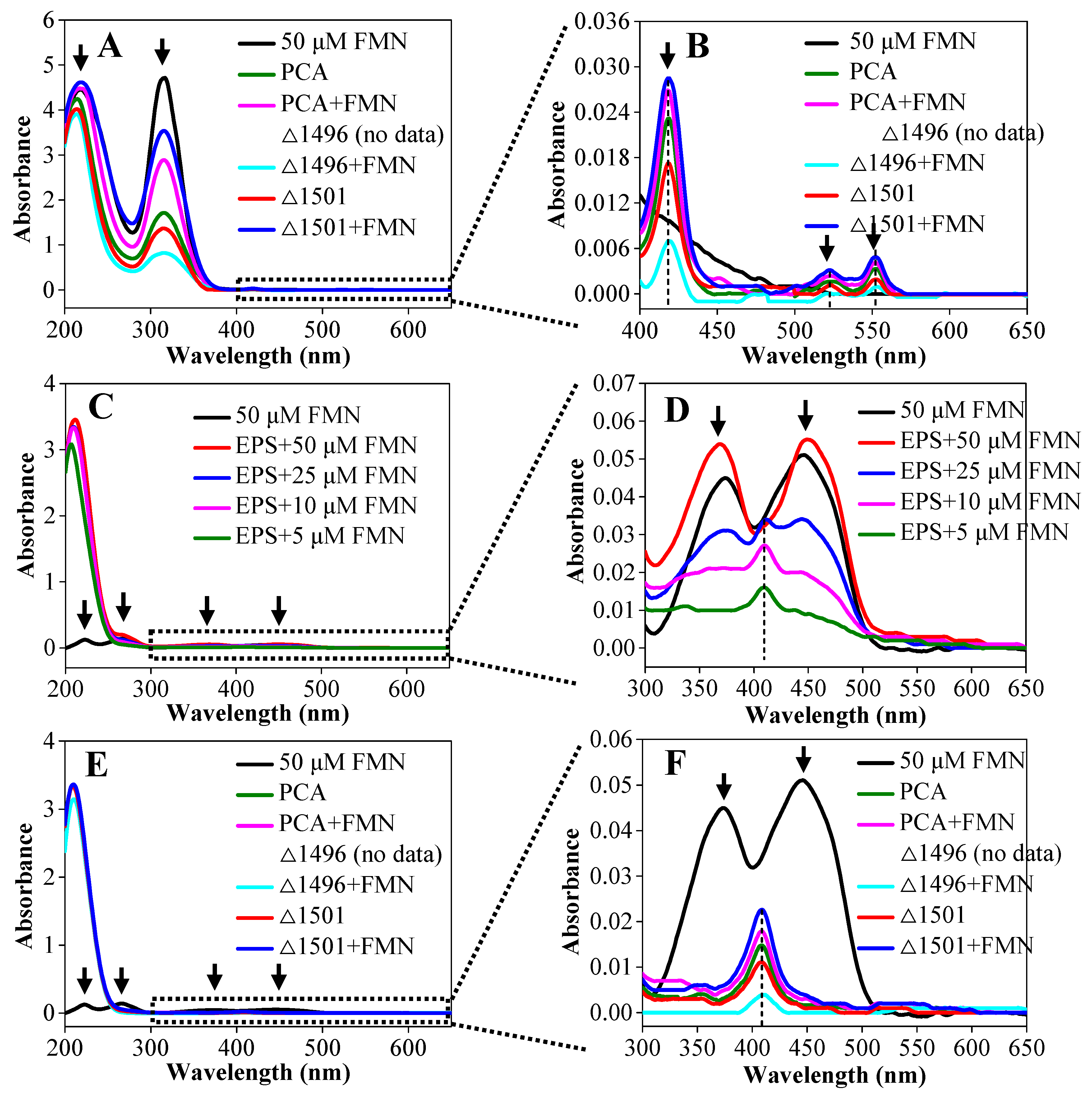

3.4. Exogenous FMN Acted as Cytochrome-Bound Cofactors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Flemming, H.C.; Wuertz, S. Bacteria and Archaea On Earth and their Abundance in Biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatan, E.; Watnick, P. Signals, Regulatory Networks, and Materials that Build and Break Bacterial Biofilms. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2009, 73, 310–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Ramnarayanan, R.; Logan, B.E. Production of Electricity During Wastewater Treatment Using a Single Chamber Microbial Fuel Cell. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 2281–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevda, S.; Sharma, S.; Joshi, C. Biofilm Formation and Electron Transfer in Bioelectrochemical Systems. Environ. Technol. Rev. 2018, 7, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghangrekar, M.M.; Chatterjee, P. A Systematic Review On Bioelectrochemical Systems Research. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2017, 3, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivase, T.J.P.; Nyakuma, B.B.; Oladokun, O.; Abu, P.T.; Hassan, M.N. Review of the Principal Mechanisms, Prospects, and Challenges of Bioelectrochemical Systems. Environ. Prog. Sustain. 2020, 39, 13298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, D.; Chetri, S.; Enerijiofi, K.E.; Naha, A.; Kanungo, T.D.; Shah, M.P.; Nath, S. Multitudinous Approaches, Challenges and Opportunities of Bioelectrochemical Systems in Conversion of Waste to Energy from Wastewater Treatment Plants. Clean. Circ. Bioecon. 2023, 4, 100040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Freguia, S.; Dennis, P.G.; Chen, X.; Donose, B.C.; Keller, J.; Gooding, J.J.; Rabaey, K. Effects of Surface Charge and Hydrophobicity On Anodic Biofilm Formation, Community Composition, and Current Generation in Bioelectrochemical Systems. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 7563–7570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Chen, J.; Huang, H.; Liu, W.; Ye, Y.; Cheng, S. The Effect of Biofilm Thickness On Electrochemical Activity of Geobacter sulfurreducens. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 16523–16528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reguera, G.; Pollina, R.B.; Nicoll, J.S.; Lovley, D.R. Possible Nonconductive Role of Geobacter sulfurreducens Pilus Nanowires in Biofilm Formation. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 2125–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reguera, G.; McCarthy, K.D.; Mehta, T.; Nicoll, J.S.; Tuominen, M.T.; Lovley, D.R. Extracellular Electron Transfer Via Microbial Nanowires. Nature 2005, 435, 1098–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Z.; Yang, G.; Zhuang, L. Exopolysaccharides Matrix Affects the Process of Extracellular Electron Transfer in Electroactive Biofilm. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Z.; Yang, G.; Mai, Q.; Guo, J.; Liu, X.; Zhuang, L. Physiological Potential of Extracellular Polysaccharide in Promoting Geobacter Biofilm Formation and Extracellular Electron Transfer. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 741, 140365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brutinel, E.D.; Gralnick, J.A. Shuttling Happens: Soluble Flavin Mediators of Extracellular Electron Transfer in Shewanella. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 93, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Hsu, L.H.H.; Kavanagh, P.; Brrière, F.; Lens, P.N.L.; Lapinsonnière, L.; Lienhard, V.J.H.; Schröder, U.; Jiang, X.; Dónal, L. The Ins and Outs of Microorganism–Electrode Electron Transfer Reactions. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017, 1, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, F.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, T.; Song, H.; Wang, Z. Microbial Extracellular Electron Transfer and Strategies for Engineering Electroactive Microorganisms. Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 53, 107682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Luo, X.; Qin, B.; Li, F.; Häggblom, M.M.; Liu, T. Enhanced Current Production by Exogenous Electron Mediators Via Synergy of Promoting Biofilm Formation and the Electron Shuttling Process. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 7217–7225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovley, D.R.; Fraga, J.L.; Coates, J.D.; Blunt Harris, E.L. Humics as an Electron Donor for Anaerobic Respiration. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 1, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Lin, J.; Zeng, E.Y.; Zhuang, L. Extraction and Characterization of Stratified Extracellular Polymeric Substances in Geobacter Biofilms. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 276, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Jing, X.; Tang, J.; Fang, Y.; Zhou, S. Quorum Sensing Signals Enhance the Electrochemical Activity and Energy Recovery of Mixed-Culture Electroactive Biofilms. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 97, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Yuan, Y.; Tang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, S. Biochar as an Electron Shuttle for Reductive Dechlorination of Pentachlorophenol by Geobacter sulfurreducens. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Jin, Y.; Zhou, D.; Liu, L.; Huang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y. A Review of the Role of Extracellular Polymeric Substances (Eps) in Wastewater Treatment Systems. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 12191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitmann, D.; Einsle, O. Structural and Biochemical Characterization of Dhc2, a Novel Diheme Cytochrome c from Geobacter sulfurreducens. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 12411–12419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, X. Ratiometric Fluorescence Detection of Riboflavin Based On Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer from Nitrogen and Phosphorus Co-Doped Carbon Dots to Riboflavin. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2019, 411, 2803–2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Hu, A.; Ren, G.; Chen, M.; Tang, J.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, S.; He, Z. Enhancing Sludge Methanogenesis with Improved Redox Activity of Extracellular Polymeric Substances by Hematite in Red Mud. Water Res. 2018, 134, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pous, N.; Carmona-Martinez, A.A.; Vilajeliu-Pons, A.; Fiset, E.; Baneras, L.; Trably, E.; Dolors Balaguer, M.; Colprim, J.; Bernet, N.; Puig, S. Bidirectional Microbial Electron Transfer: Switching an Acetate Oxidizing Biofilm to Nitrate Reducing Conditions. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 75, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, A.; Hashimoto, K.; Nealson, K.H.; Nakamura, R. Rate Enhancement of Bacterial Extracellular Electron Transport Involves Bound Flavin Semiquinones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 7856–7861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhang, E.; Zhang, J.; Dai, Y.; Yang, Z.; Christensen, H.E.M.; Ulstrup, J.; Zhao, F. Extracellular Polymeric Substances are Transient Media for Microbial Extracellular Electron Transfer. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borole, A.P.; Reguera, G.; Ringeisen, B.; Wang, Z.; Feng, Y.; Kim, B.H. Electroactive Biofilms: Current Status and Future Research Needs. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 4813–4834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Peng, P.; Li, X.; Zhou, X.; Chen, L.; Zhao, F. Unlocking Anaerobic Digestion Potential via Extracellular Electron Transfer by Exogenous Materials: Current Status and Perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 416, 131734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, A.; Nakamura, R.; Nealson, K.H.; Hashimoto, K. Bound Flavin Model Suggests Similar Electron-Transfer Mechanisms in Shewanella and Geobacter. ChemElectroChem 2014, 1, 1808–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Tang, J.; Chen, M.; Liu, X.; Zhou, S. Two Modes of Riboflavin-Mediated Extracellular Electron Transfer in Geobacter uraniireducens. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Singh, L.; Zularisam, A.W. Exoelectrogens: Recent Advances in Molecular Drivers Involved in Extracellular Electron Transfer and Strategies Used to Improve It for Microbial Fuel Cell Applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 56, 1322–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueki, T. Cytochromes in Extracellular Electron Transfer in Geobacter. Appl. Environ. Microb. 2021, 87, e3109–e3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, X.; Liu, X.; Dong, H.; Lin, M.; Zheng, X.; Yang, Q. Implementation of Cytochrome c Proteins and Carbon Nanotubes Hybrids in Bioelectrodes Towards Bioelectrochemical Systems Applications. Bioproc. Biosyst. Eng. 2024, 47, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, A.; Saito, K.; Inoue, K.; Nealson, K.H.; Hashimoto, K.; Nakamura, R. Uptake of Self-Secreted Flavins as Bound Cofactors for Extracellular Electron Transfer in Geobacter Species. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 1357–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhuang, Z.; Shi, Y.; Yang, G.; Zhuang, L. The Restorative Effects of Electron Mediators on the Formation of Electroactive Biofilms in Geobacter sulfurreducens. Microorganisms 2026, 14, 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010214

Zhuang Z, Shi Y, Yang G, Zhuang L. The Restorative Effects of Electron Mediators on the Formation of Electroactive Biofilms in Geobacter sulfurreducens. Microorganisms. 2026; 14(1):214. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010214

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhuang, Zheng, Yue Shi, Guiqin Yang, and Li Zhuang. 2026. "The Restorative Effects of Electron Mediators on the Formation of Electroactive Biofilms in Geobacter sulfurreducens" Microorganisms 14, no. 1: 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010214

APA StyleZhuang, Z., Shi, Y., Yang, G., & Zhuang, L. (2026). The Restorative Effects of Electron Mediators on the Formation of Electroactive Biofilms in Geobacter sulfurreducens. Microorganisms, 14(1), 214. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms14010214