Global Epidemiology and Antimicrobial Resistance of Klebsiella Pneumoniae Carbapenemase (KPC)-Producing Gram-Negative Clinical Isolates: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Objectives

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Selection Process

2.5. Data Extraction

3. Results

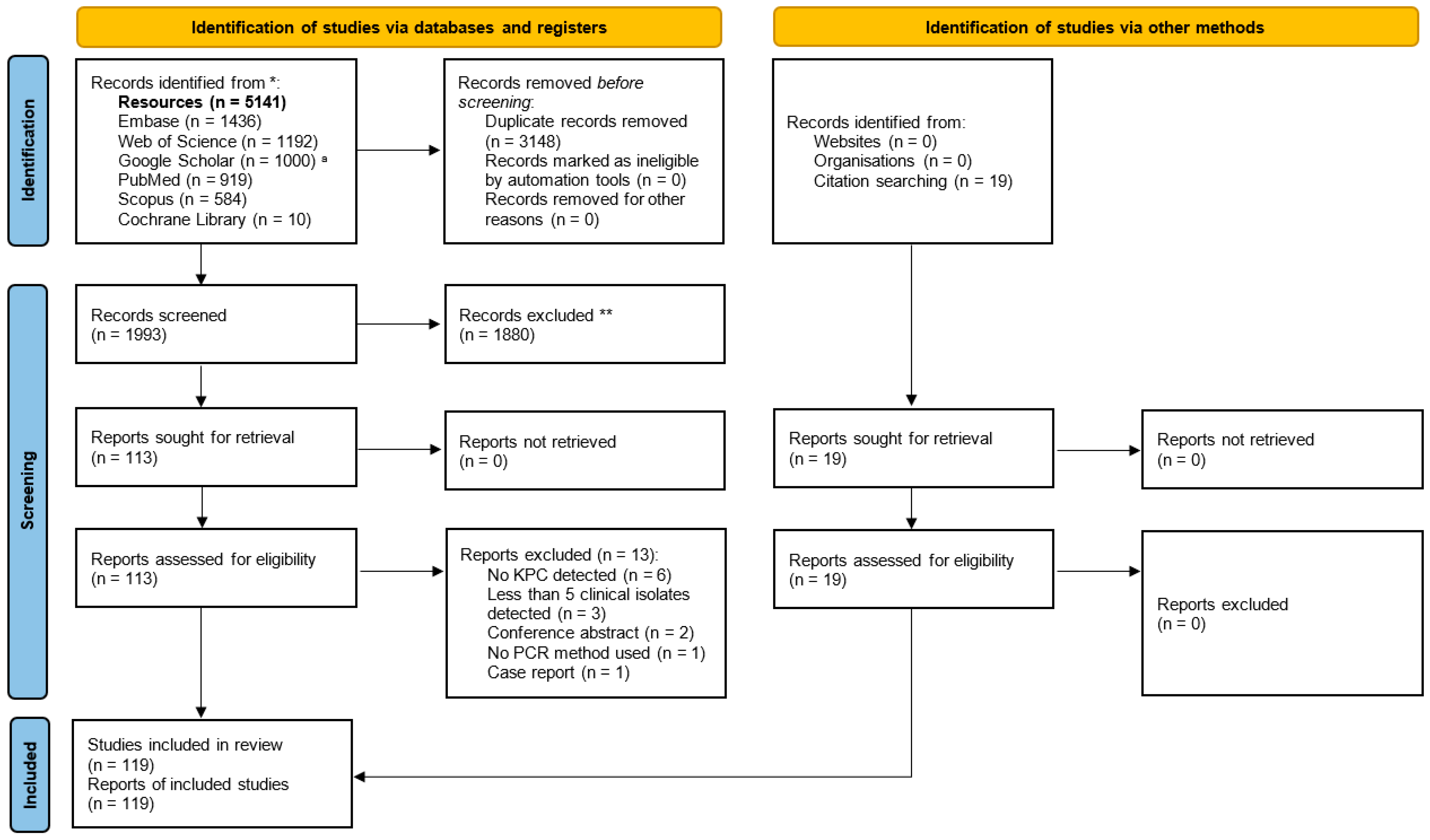

3.1. Selection of Relevant Articles

3.2. Results of Individual Studies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| EUCAST | European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| HAP | healthcare-associated pneumonia |

| KPC | Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase |

| MBL | metallo-β-lactamase |

| NDM | New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase |

| PCR | polymerase chain reaction |

| SSTI | skin and soft tissue infection |

| ST | sequence type |

| UTI | urinary tract infection |

| VAP | ventilator-associated pneumonia |

References

- Lim, C.; Hantrakun, V.; Klaytong, P.; Rangsiwutisak, C.; Tangwangvivat, R.; Phiancharoen, C.; Doung-ngern, P.; Kripattanapong, S.; Hinjoy, S.; Yingyong, T.; et al. Frequency and Mortality Rate Following Antimicrobial-Resistant Bloodstream Infections in Tertiary-Care Hospitals Compared with Secondary-Care Hospitals. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulingam, T.; Parumasivam, T.; Gazzali, A.M.; Sulaiman, A.M.; Chee, J.Y.; Lakshmanan, M.; Chin, C.F.; Sudesh, K. Antimicrobial Resistance: Prevalence, Economic Burden, Mechanisms of Resistance and Strategies to Overcome. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 170, 106103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naghavi, M.; Vollset, S.E.; Ikuta, K.S.; Swetschinski, L.R.; Gray, A.P.; Wool, E.E.; Aguilar, G.R.; Mestrovic, T.; Smith, G.; Han, C.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance 1990–2021: A Systematic Analysis with Forecasts to 2050. Lancet 2024, 404, 1199–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babic, M.; Hujer, A.M.; Bonomo, R.A. What’s New in Antibiotic Resistance? Focus on Beta-Lactamases. Drug Resist. Updates 2006, 9, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambler, R.P.; Baddiley, J.; Abraham, E.P. The Structure of β-Lactamases. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1997, 289, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tooke, C.L.; Hinchliffe, P.; Bragginton, E.C.; Colenso, C.K.; Hirvonen, V.H.A.; Takebayashi, Y.; Spencer, J. β-Lactamases and β-Lactamase Inhibitors in the 21st Century. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 3472–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, F.; Cui, S.; Mao, L.; Li, X.; Awan, F.; Lv, W.; Zeng, Z. Prevalence and Distribution Characteristics of BlaKPC-2 and BlaNDM-1 Genes in Klebsiella Pneumoniae. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 2901–2910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnin, R.A.; Jousset, A.B.; Chiarelli, A.; Emeraud, C.; Glaser, P.; Naas, T.; Dortet, L. Emergence of New Non-Clonal Group 258 High-Risk Clones among Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase-Producing K. Pneumoniae Isolates, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1212–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Mathema, B.; Chavda, K.D.; DeLeo, F.R.; Bonomo, R.A.; Kreiswirth, B.N. Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae: Molecular and Genetic Decoding. Trends Microbiol 2014, 22, 686–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Tang, Y.; Fu, P.; Tian, D.; Yu, L.; Huang, Y.; Li, G.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Z.; et al. The Type I-E CRISPR-Cas System Influences the Acquisition of blaKPC-IncF Plasmid in Klebsiella Pneumonia. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 1011–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budia-Silva, M.; Kostyanev, T.; Ayala-Montaño, S.; Bravo-Ferrer Acosta, J.; Garcia-Castillo, M.; Cantón, R.; Goossens, H.; Rodriguez-Baño, J.; Grundmann, H.; Reuter, S. International and Regional Spread of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Europe. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripabelli, G.; Sammarco, M.L.; Scutellà, M.; Felice, V.; Tamburro, M. Carbapenem-Resistant KPC- and TEM-Producing Escherichia coli ST131 Isolated from a Hospitalized Patient with Urinary Tract Infection: First Isolation in Molise Region, Central Italy, July 2018. Microb. Drug Resist. 2020, 26, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miriagou, V.; Cornaglia, G.; Edelstein, M.; Galani, I.; Giske, C.G.; Gniadkowski, M.; Malamou-Lada, E.; Martinez-Martinez, L.; Navarro, F.; Nordmann, P.; et al. Acquired Carbapenemases in Gram-Negative Bacterial Pathogens: Detection and Surveillance Issues. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2010, 16, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Tansarli, G.S.; Karageorgopoulos, D.E.; Vardakas, K.Z. Deaths Attributable to Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae Infections. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 1170–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassetti, M.; Peghin, M. How to Manage KPC Infections. Ther. Adv. Infect. 2020, 7, 2049936120912049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantón, R.; Akóva, M.; Carmeli, Y.; Giske, C.G.; Glupczynski, Y.; Gniadkowski, M.; Livermore, D.M.; Miriagou, V.; Naas, T.; Rossolini, G.M.; et al. Rapid Evolution and Spread of Carbapenemases among Enterobacteriaceae in Europe. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzidimitriou, M.; Kavvada, A.; Kavvadas, D.; Kyriazidi, M.A.; Eleftheriadis, K.; Varlamis, S.; Papaliagkas, V.; Mitka, S. Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in the Balkans: Clonal Distribution and Associated Resistance Determinants. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2024, 71, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djahmi, N.; Dunyach-Remy, C.; Pantel, A.; Dekhil, M.; Sotto, A.; Lavigne, J.-P. Epidemiology of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter Baumannii in Mediterranean Countries. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 305784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, G.T. Continuous Evolution: Perspective on the Epidemiology of Carbapenemase Resistance Among Enterobacterales and Other Gram-Negative Bacteria. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2021, 10, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Lu, X.; Xu, H.; Ma, X.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hong, G.; Liang, X. Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae Colonisation and Infections: Case-Controlled Study from an Academic Medical Center in a Southern Area of China. Pathog. Dis. 2019, 77, ftz034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Zhou, Y.; Jin, H.; Liu, K.; Zhu, K.; Yu, Y.; Xue, J.; Wang, Q.; Du, X.; Wang, H.; et al. Genomic Insights and Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles of CRKP and Non-CRKP Isolates in a Beijing Geriatric Medical Center: Emphasizing the blaKPC-2 Carrying High-Risk Clones and Their Spread. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1359340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Shi, Q.; Wu, S.; Yin, D.; Peng, M.; Dong, D.; Zheng, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, R.; Hu, F.; et al. Dissemination of Carbapenemases (KPC, NDM, OXA-48, IMP, and VIM) Among Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae Isolated from Adult and Children Patients in China. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, C.; Shen, Z.; Zhou, H.; Cao, J.; Chen, S.; Lv, H.; Zhou, M.; Wang, Q.; Sun, L.; et al. Prevalence, Risk Factors and Molecular Epidemiology of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Patients from Zhejiang, China, 2008–2018. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 1771–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Z.; Wang, Z.; Gong, L.; Yi, L.; Liu, N.; Luo, L.; Gong, W. Molecular Epidemiological Characteristics of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae among Children in China. AMB Express 2022, 12, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jing, N.; Yan, W.; Zhang, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Wei, X.; Zhao, W.; Guo, S.; Guo, L.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, L.; et al. Epidemiology and Genotypic Characteristics of Carbapenem Resistant Enterobacterales in Henan, China: A Multicentre Study. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2022, 29, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.; Zheng, W.; Kong, Z.; Jiang, F.; Gu, B.; Ma, P.; Ma, X. Disease Burden and Molecular Epidemiology of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumonia Infection in a Tertiary Hospital in China. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, Z.; Tang, M.; Min, C.; Xia, F.; Hu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhou, H.; Zou, M. Clonal Dissemination of Multiple Carbapenemase Genes in Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales Mediated by Multiple Plasmids in China. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 3287–3295. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Y.; Zhao, C.; Lu, Y.; Liao, K.; Kong, Y.; Hong, M.; Li, L.; Chen, Y. Microbiological Characteristics, Risk Factors, and Short-Term Mortality of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae Bloodstream Infections in Pediatric Patients in China: A 10-Year Longitudinal Study. Infect. Drug Resist. 2024, 17, 4815–4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Gong, J.; Yuan, X.; Lu, H.; Jiang, L. Drug Resistance Genes and Molecular Epidemiological Characteristics of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumonia. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, 16, 1511–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Huang, N.; Zhou, C.; Lin, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zheng, X.; Zhou, T.; Wang, Z. Molecular Mechanisms and Epidemiology of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacter Cloacae Complex Isolated from Chinese Patients During 2004–2018. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 3647–3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Gao, K.; Li, M.; Zhou, J.; Song, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Yu, Z.; Cheng, W.; Zhang, W.; et al. Epidemiological and Molecular Characteristics of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae from Pediatric Patients in Henan, China. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2024, 23, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Feng, D.-H.; Zhan, Y.; Wang, Q.; Chen, D.-Q.; Xu, Z.; Yang, L. Molecular Epidemiology, Microbial Virulence, and Resistance of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales Isolates in a Teaching Hospital in Guangzhou, China. Microb. Drug Resist. 2022, 28, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, M.; Chen, X.; He, J.; Xiong, L.; Tian, R.; Yang, G.; Zha, H.; Wu, K. Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns, Sequence Types, Virulence and Carbapenemase Genes of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Clinical Isolates from a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital in Zunyi, China. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, 16, 637–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Q.; Ruan, Z.; Zhang, P.; Hu, H.; Han, X.; Wang, Z.; Lou, T.; Quan, J.; Lan, W.; Weng, R.; et al. Epidemiology of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in China and the Evolving Trends of Predominant Clone ST11: A Multicentre, Genome-Based Study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2024, 79, 2292–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, D.; Pan, F.; Wang, C.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, H. Resistance Phenotype and Clinical Molecular Epidemiology of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae among Pediatric Patients in Shanghai. Infect. Drug Resist. 2018, 11, 1935–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Zheng, X.; Sun, Y.; Fang, R.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Lin, J.; Cao, J.; Zhou, T. Molecular Mechanisms and Epidemiology of Carbapenem-Resistant Escherichia coli Isolated from Chinese Patients During 2002–2017. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Ouyang, P.; Jin, C.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, L.; Chen, H.; Wang, Z.; et al. Phenotypic and Genotypic Characterization of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae: Data from a Longitudinal Large-Scale CRE Study in China (2012–2016). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 67, S196–S205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Dong, H.; Wang, M.; Ma, W.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, J.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, H.; Yu, X. Molecular Epidemiology of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Tertiary Hospital in Northern China. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2022, 2022, 2615753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yu, F.; Shen, X.; Li, M. A Polyclonal Spread Emerged: Characteristics of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates from the Intensive Care Unit in a Chinese Tertiary Hospital. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2020, 69, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Zou, C.; Qin, J.; Tao, J.; Yan, L.; Wang, J.; Du, H.; Shen, F.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, H. Emergence of Hypervirulent ST11-K64 Klebsiella pneumoniae Poses a Serious Clinical Threat in Older Patients. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 765624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, G.; Li, J.; Wang, T.; Kang, W.; Zhang, J.; Sun, H.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y. In-Vitro Activities of Essential Antimicrobial Agents Including Aztreonam/Avibactam, Eravacycline, Colistin and Other Comparators against Carbapenem-Resistant Bacteria with Different Carbapenemase Genes: A Multi-Centre Study in China, 2021. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2024, 64, 107341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.J.; Jing, N.; Wang, S.M.; Xu, J.H.; Yuan, Y.H.; Zhang, Q.; Li, A.L.; Chen, L.H.; Zhang, J.F.; Ma, B.; et al. Molecular Characterization of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae and Emergence of Tigecycline Non-Susceptible Strains in the Henan Province in China: A Multicentrer Study. J. Med. Microbiol. 2021, 70, 001325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ye, L.; Guo, L.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, R.; Luo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Tian, S.; Zhao, J.; Shen, D.; et al. A Nosocomial Outbreak of KPC-2-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Chinese Hospital: Dissemination of ST11 and Emergence of ST37, ST392 and ST395. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2013, 19, E509–E515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.-X.; Chen, H.-Y.; Chen, C.; Chen, J.-H.; Wan, F.-S.; Li, L.-X.; Chen, M.; Zhang, J. Resistance Phenotype and Molecular Epidemiology of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates in Shanghai. Microb. Drug Resist. 2021, 27, 1312–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, A.; Miller-Roll, T.; Assous, M.V.; Geffen, Y.; Paikin, S.; Schwartz, D.; Weiner-Well, Y.; Hussein, K.; Cohen, R.; Carmeli, Y. A Multicenter Study of the Clonal Structure and Resistance Mechanism of KPC-Producing Escherichia coli Isolates in Israel. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, A.; Navon-Venezia, S.; Moran-Gilad, J.; Marcos, E.; Schwartz, D.; Carmeli, Y. Laboratory and Clinical Evaluation of Screening Agar Plates for Detection of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae from Surveillance Rectal Swabs. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 2239–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-David, D.; Maor, Y.; Keller, N.; Regev-Yochay, G.; Tal, I.; Shachar, D.; Zlotkin, A.; Smollan, G.; Rahav, G. Potential Role of Active Surveillance in the Control of a Hospital-Wide Outbreak of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Infection. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2015, 31, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, K.; Geffen, Y.; Eluk, O.; Warman, S.; Aboalheja, W.; Alon, T.; Firan, I.; Paul, M. The Changing Epidemiology of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacterales. Rambam Maimonides Med. J. 2022, 13, e0004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manandhar, S.; Zellweger, R.M.; Maharjan, N.; Dongol, S.; Prajapati, K.G.; Thwaites, G.; Basnyat, B.; Dixit, S.M.; Baker, S.; Karkey, A. A High Prevalence of Multi-Drug Resistant Gram-Negative Bacilli in a Nepali Tertiary Care Hospital and Associated Widespread Distribution of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase (ESBL) and Carbapenemase-Encoding Genes. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2020, 19, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sah, R.; Bhattarai, S.; Basnet, S.; Mani Pokhrel, B.; Prasad Shah, N.; Sah, S.; Sah, R.; Dhama, K.; Rijal, B. A Prospective Study on Neonatal Sepsis in a Tertiary Hospital, Nepal. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 15, 2409–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, T.; Tada, T.; Shrestha, S.; Hishinuma, T.; Sherchan, J.B.; Tohya, M.; Kirikae, T.; Sherchand, J.B. Molecular Characterisation of Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Clinical Isolates in Nepal. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 26, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, M.L.; Tee, Y.M.; Tan, S.G.; Amin, I.M.; How, K.B.; Tan, K.Y.; Lee, L.C. Risk Factors for Acquisition of Carbapenem Resistant Enterobacteriaceae in an Acute Tertiary Care Hospital in Singapore. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2015, 4, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, J.W.P.; Tan, P.; La, M.-V.; Krishnan, P.; Tee, N.; Koh, T.H.; Deepak, R.N.; Tan, T.Y.; Jureen, R.; Lin, R.T.P. Surveillance Trends of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae from Singapore, 2010–2013. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2014, 2, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, J.Q.-M.; Tang, C.Y.; Tan, S.H.; Chang, H.Y.; Ong, S.M.; Lee, S.J.-Y.; Koh, T.-H.; Sim, J.H.-C.; Kwa, A.L.-H.; Ong, R.T.-H. Genomic Surveillance of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae from a Major Public Health Hospital in Singapore. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0095722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S.-K.; Wu, T.-L.; Chuang, Y.-C.; Lin, J.-C.; Fung, C.-P.; Lu, P.-L.; Wang, J.-T.; Wang, L.-S.; Siu, L.K.; Yeh, K.-M. National Surveillance Study on Carbapenem Non-Susceptible Klebsiella pneumoniae in Taiwan: The Emergence and Rapid Dissemination of KPC-2 Carbapenemase. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e69428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.-S.; Chen, P.-Y.; Chou, P.-C.; Wang, J.-T. In Vitro Activities and Inoculum Effects of Cefiderocol and Aztreonam-Avibactam against Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0056923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.-L.; Ko, W.-C.; Lee, W.-S.; Lu, P.-L.; Chen, Y.-H.; Cheng, S.-H.; Lu, M.-C.; Lin, C.-Y.; Wu, T.-S.; Yen, M.-Y.; et al. In-Vitro Activity of Cefiderocol, Cefepime/Zidebactam, Cefepime/Enmetazobactam, Omadacycline, Eravacycline and Other Comparative Agents against Carbapenem-Nonsusceptible Enterobacterales: Results from the Surveillance of Multicenter Antimicrobial Resistance in Taiwan (SMART) in 2017–2020. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2021, 58, 106377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Im, J.H.; Shim, J.Y.; Lee, H.J.; Hyun, J.H.; Lee, S.J.; Park, S.K. Status of Reported Cases of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) Infections in Korea, 2022. Public Health Wkly. Rep. 2024, 17, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, E.H.; Hong, H.-L.; Kim, E.J. Epidemiology and Mortality Analysis Related to Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales in Patients After Admission to Intensive Care Units: An Observational Study. Infect. Drug Resist. 2023, 16, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, B.; Hoang, N.T.B.; Tärnberg, M.; Le, N.K.; Nilsson, M.; Khu, D.T.K.; Svartström, O.; Welander, J.; Nilsson, L.E.; Olson, L.; et al. Molecular and Phenotypic Characterization of Clinical Isolates Belonging to a KPC-2-Producing Strain of ST15 Klebsiella pneumoniae from a Vietnamese Pediatric Hospital. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2019, 8, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linh, T.D.; Thu, N.H.; Shibayama, K.; Suzuki, M.; Yoshida, L.; Thai, P.D.; Anh, D.D.; Duong, T.N.; Trinh, H.S.; Thom, V.P.; et al. Expansion of KPC-Producing Enterobacterales in Four Large Hospitals in Hanoi, Vietnam. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2021, 27, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlAmri, A.M.; AlQurayan, A.M.; Sebastian, T.; AlNimr, A.M. Molecular Surveillance of Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter Baumannii. Curr. Microbiol. 2019, 77, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.S.; Shah, H.; Singh, B.N.; Chandi, D.H.; Deb, M.; Jha, R. Molecular Detection of Carbapenem Resistance in Clinical Isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae in Tertiary Care Hospital. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 17, 1109–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darabi, N.; Motazakker, M.; Khalkhali, H.R.; Yousefi, S. A Multicenter Study of β-Lactamase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolated from University Teaching Hospitals of Urmia, Iran. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2019, 13, 690–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falco, A.; Ramos, Y.; Franco, E.; Guzmán, A.; Takiff, H. A Cluster of KPC-2 and VIM-2-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST833 Isolates from the Pediatric Service of a Venezuelan Hospital. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yürek, M.; Cevahir, N. Investigation of Virulence Genes and Carbapenem Resistance Genes in Hypervirulent and Classical Isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolated from Various Clinical Specimens. Mikrobiyol. Bul. 2023, 57, 188–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidelshtein, M.V.; Shaidullina, E.R.; Ivanchik, N.V.; Dekhnich, A.V.; Mikotina, A.V.; Skleenova, E.Y.; Sukhorukova, M.V.; Azizov, I.S.; Shek, E.A.; Romanov, A.V.; et al. Antibiotic Resistance of Clinical Isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli in Russian Hospitals: Results of a Multicenter Epidemiological Study. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2024, 26, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontopidou, F.; Giamarellou, H.; Katerelos, P.; Maragos, A.; Kioumis, I.; Trikka-Graphakos, E.; Valakis, C.; Maltezou, H.C. Group for the Study of KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae infections in intensive care units Infections Caused by Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae among Patients in Intensive Care Units in Greece: A Multi-Centre Study on Clinical Outcome and Therapeutic Options. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20, O117–O123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pournaras, S.; Zarkotou, O.; Poulou, A.; Kristo, I.; Vrioni, G.; Themeli-Digalaki, K.; Tsakris, A. A Combined Disk Test for Direct Differentiation of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in Surveillance Rectal Swabs. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 2986–2990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorovou, G.; Schinas, G.; Pasxali, A.; Tzoukmani, A.; Tryfinopoulou, K.; Gogos, C.; Dimopoulos, G.; Akinosoglou, K. Epidemiology and Resistance Phenotypes of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Corfu General Hospital (2019–2022): A Comprehensive Time Series Analysis of Resistance Gene Dynamics. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarras, C.; Pappa, S.; Zarras, K.; Karampatakis, T.; Vagdatli, E.; Mouloudi, E.; Iosifidis, E.; Roilides, E.; Papa, A. Changes in Molecular Epidemiology of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in the Intensive Care Units of a Greek Hospital, 2018–2021. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2022, 69, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agodi, A.; Voulgari, E.; Barchitta, M.; Politi, L.; Koumaki, V.; Spanakis, N.; Giaquinta, L.; Valenti, G.; Romeo, M.A.; Tsakris, A. Containment of an Outbreak of KPC-3-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Italy. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 3986–3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orena, B.S.; Liporace, M.F.; Teri, A.; Girelli, D.; Salari, F.; Mutti, M.; Giordano, G.; Alteri, C.; Gentiloni Silverj, F.; Matinato, C.; et al. Active Surveillance of Patients Colonized with CRE: A Single-Center Study Based on a Combined Molecular/Culture Protocol. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piazza, A.; Mattioni Marchetti, V.; Bielli, A.; Biffignandi, G.B.; Piscopiello, F.; Giudici, R.; Tartaglione, L.; Merli, M.; Vismara, C.; Migliavacca, R. A Novel KPC-166 in Ceftazidime/Avibactam Resistant ST307 Klebsiella pneumoniae Causing an Outbreak in Intensive Care COVID Unit, Italy. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2024, 57, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santino, I.; Bono, S.; Nuccitelli, A.; Martinelli, D.; Petrucci, C.; Alari, A. Microbiological and Molecular Characterization of Extreme Drug-Resistant Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2013, 26, 785–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzek, A.; Rybicki, Z.; Tomaszewski, D. An Analysis of the Type and Antimicrobial Resistance of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae Isolated at the Military Institute of Medicine in Warsaw, Poland, 2009–2016. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 2019, 12, e67823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuch, A.; Zieniuk, B.; Żabicka, D.; Van de Velde, S.; Literacka, E.; Skoczyńska, A.; Hryniewicz, W. Activity of Temocillin against ESBL-, AmpC-, and/or KPC-Producing Enterobacterales Isolated in Poland. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 39, 1185–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrowiec, P.; Klesiewicz, K.; Małek, M.; Skiba-Kurek, I.; Sowa-Sierant, I.; Skałkowska, M.; Budak, A.; Karczewska, E. Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Prevalence of Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamases in Clinical Strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolated from Pediatric and Adult Patients of Two Polish Hospitals. New Microbiol. 2019, 42, 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Buzgó, L.; Kiss, Z.; Göbhardter, D.; Lesinszki, V.; Ungvári, E.; Rádai, Z.; Laczkó, L.; Damjanova, I.; Kardos, G.; Tóth, Á. High Prevalence of Cefiderocol Resistance Among New Delhi Metallo-β-Lactamase Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae High-Risk Clones in Hungary. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, Á.; Damjanova, I.; Puskás, E.; Jánvári, L.; Farkas, M.; Dobák, A.; Böröcz, K.; Pászti, J. Emergence of a Colistin-Resistant KPC-2-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 Clone in Hungary. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2010, 29, 765–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoenigl, M.; Valentin, T.; Zarfel, G.; Wuerstl, B.; Leitner, E.; Salzer, H.J.F.; Posch, J.; Krause, R.; Grisold, A.J. Nosocomial Outbreak of Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella Oxytoca in Austria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 2158–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Laveleye, M.; Huang, T.D.; Bogaerts, P.; Berhin, C.; Bauraing, C.; Sacré, P.; Noel, A.; Glupczynski, Y.; Multicenter Study Group. Increasing Incidence of Carbapenemase-Producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae in Belgian Hospitals. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 36, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobreva, E.; Ivanov, I.; Donchev, D.; Ivanova, K.; Hristova, R.; Dobrinov, V.; Dobrinov, V.; Sabtcheva, S.; Kantardjiev, T. In Vitro Investigation of Antibiotic Combinations against Multi- and Extensively Drug-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 10, 1308–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerum, A.M.; Lauridsen, C.A.S.; Blem, S.L.; Roer, L.; Hansen, F.; Henius, A.E.; Holzknecht, B.J.; Søes, L.; Andersen, L.P.; Røder, B.L.; et al. Investigation of Possible Clonal Transmission of Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Complex Member Isolates in Denmark Using Core Genome MLST and National Patient Registry Data. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Räisänen, K.; Lyytikäinen, O.; Kauranen, J.; Tarkka, E.; Forsblom-Helander, B.; Grönroos, J.O.; Vuento, R.; Arifulla, D.; Sarvikivi, E.; Toura, S.; et al. Molecular Epidemiology of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacterales in Finland, 2012–2018. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020, 39, 1651–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonne, A.; Thiolet, J.M.; Fournier, S.; Fortineau, N.; Kassis-Chikhani, N.; Boytchev, I.; Aggoune, M.; Seguier, J.C.; Senechal, H.; Tavolacci, M.P.; et al. Control of a Multi-Hospital Outbreak of KPC-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Type 2 in France, September to October 2009. Euro Surveill. 2010, 15, 19734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, D.; Boyle, F.; Morris, C.; Condon, I.; Delannoy-Vieillard, A.-S.; Power, L.; Khan, A.; Morris-Downes, M.; Finnegan, C.; Powell, J.; et al. Inter-Hospital Outbreak of Klebsiella pneumoniae Producing KPC-2 Carbapenemase in Ireland. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 2367–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamin, C.; Notermans, D.W.; Beuken, E.; Maat, I.; Lansu, S.; Witteveen, S.; Landman, F.; van Alphen, L.; Oteo-Iglesias, J.; Carattoli, A.; et al. KPC-85, a Carbapenemase-Producing and Ceftazidime-Avibactam-Resistant KPC-3 Variant Found in Klebsiella pneumoniae ST512 in the Netherlands. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2024, 64, 107271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelsen, Ø.; Overballe-Petersen, S.; Bjørnholt, J.V.; Brisse, S.; Doumith, M.; Woodford, N.; Hopkins, K.L.; Aasnæs, B.; Haldorsen, B.; Sundsfjord, A.; et al. Molecular and Epidemiological Characterization of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in Norway, 2007 to 2014. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baicus, A.; Lixandru, B.; Stroia, M.; Cirstoiu, M.; Constantin, A.; Usein, C.R.; Cirstoiu, C.F. Antimicrobial Susceptibility and Molecular Epidemiology of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Strains Isolated in an Emergency University Hospital. Biotechnol. Lett. 2018, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Gracia-Ahufinger, I.; López-González, L.; Vasallo, F.J.; Galar, A.; Siller, M.; Pitart, C.; Bloise, I.; Torrecillas, M.; Gijón-Cordero, D.; Viñado, B.; et al. The CARBA-MAP Study: National Mapping of Carbapenemases in Spain (2014–2018). Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1247804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnin, R.A.; Creton, E.; Perrin, A.; Girlich, D.; Emeraud, C.; Jousset, A.B.; Duque, M.; Jacquemin, A.; Hopkins, K.; Bogaerts, P.; et al. Spread of Carbapenemase-Producing Morganella spp. from 2013 to 2021: A Comparative Genomic Study. Lancet Microbe 2024, 5, e547–e558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, S.; Reuter, S.; Harris, S.R.; Glasner, C.; Feltwell, T.; Argimon, S.; Abudahab, K.; Goater, R.; Giani, T.; Errico, G.; et al. Epidemic of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Europe Is Driven by Nosocomial Spread. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 1919–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazmierczak, K.M.; de Jonge, B.L.M.; Stone, G.G.; Sahm, D.F. Longitudinal Analysis of ESBL and Carbapenemase Carriage among Enterobacterales and Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Isolates Collected in Europe as Part of the International Network for Optimal Resistance Monitoring (INFORM) Global Surveillance Programme, 2013–2017. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 1165–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundmann, H.; Glasner, C.; Albiger, B.; Aanensen, D.M.; Tomlinson, C.T.; Andrasević, A.T.; Cantón, R.; Carmeli, Y.; Friedrich, A.W.; Giske, C.G.; et al. Occurrence of Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli in the European Survey of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae (EuSCAPE): A Prospective, Multinational Study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, P.A.; Bratu, S.; Urban, C.; Visalli, M.; Mariano, N.; Landman, D.; Rahal, J.J.; Brooks, S.; Cebular, S.; Quale, J. Emergence of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella Species Possessing the Class A Carbapenem-Hydrolyzing KPC-2 and Inhibitor-Resistant TEM-30 Beta-Lactamases in New York City. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 39, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanheira, M.; Mendes, R.E.; Sader, H.S. Low Frequency of Ceftazidime-Avibactam Resistance among Enterobacteriaceae Isolates Carrying blaKPC Collected in U.S. Hospitals from 2012 to 2015. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e02369-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endimiani, A.; Depasquale, J.M.; Forero, S.; Perez, F.; Hujer, A.M.; Roberts-Pollack, D.; Fiorella, P.D.; Pickens, N.; Kitchel, B.; Casiano-Colón, A.E.; et al. Emergence of blaKPC-Containing Klebsiella pneumoniae in a Long-Term Acute Care Hospital: A New Challenge to Our Healthcare System. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2009, 64, 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, M.A.; Suda, K.J.; Ramanathan, S.; Wilson, G.; Poggensee, L.; Evans, M.; Jones, M.M.; Pfeiffer, C.D.; Klutts, J.S.; Perencevich, E.; et al. Increased Carbapenemase Testing Following Implementation of National VA Guidelines for Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales (CRE). Antimicrob. Steward. Healthc. Epidemiol. 2022, 2, e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Simmonds, A.; Annavajhala, M.K.; McConville, T.H.; Dietz, D.E.; Shoucri, S.M.; Laracy, J.C.; Rozenberg, F.D.; Nelson, B.; Greendyke, W.G.; Furuya, E.Y.; et al. Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacterales Causing Secondary Infections during the COVID-19 Crisis at a New York City Hospital. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, R.M.; Castanheira, M.; Jones, R.N.; Tenover, F.; Lynfield, R. Trends in Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase-Positive K. Pneumoniae in US Hospitals: Report from the 2007–2009 SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013, 76, 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, L.K.; Nguyen, D.C.; Scaggs Huang, F.A.; Qureshi, N.K.; Charnot-Katsikas, A.; Bartlett, A.H.; Zheng, X.; Hujer, A.M.; Domitrovic, T.N.; Marshall, S.H.; et al. A Multi-Centered Case-Case-Control Study of Factors Associated with Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae Infections in Children and Young Adults. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2019, 38, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Precit, M.R.; Kauber, K.; Glover, W.A.; Weissman, S.J.; Robinson, T.; Tran, M.; D’Angeli, M. Statewide Surveillance of Carbapenemase-Producing Carbapenem-Resistant Escherichia coli and Klebsiella Species in Washington State, October 2012–December 2017. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2020, 41, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shortridge, D.; Kantro, V.; Castanheira, M. Meropenem-Vaborbactam Activity against U.S. Multidrug-Resistant Enterobacterales Strains, Including Carbapenem-Resistant Isolates. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0450722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Duin, D.; Arias, C.A.; Komarow, L.; Chen, L.; Hanson, B.M.; Weston, G.; Cober, E.; Garner, O.B.; Jacob, J.T.; Satlin, M.J.; et al. Molecular and Clinical Epidemiology of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales in the USA (CRACKLE-2): A Prospective Cohort Study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 731–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, M.; Lutgring, J.D.; Ansari, U.; Lawsin, A.; Albrecht, V.; McAllister, G.; Daniels, J.; Lonsway, D.; McKay, S.L.; Beldavs, Z.; et al. Molecular Characterization of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales Collected in the United States. Microb. Drug Resist. 2022, 28, 389–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, M.R.; Abdelhamed, A.M.; Good, C.E.; Rhoads, D.D.; Hujer, K.M.; Hujer, A.M.; Domitrovic, T.N.; Rudin, S.D.; Richter, S.S.; Van Duin, D.; et al. ARGONAUT-I: Activity of Cefiderocol (S-649266), a Siderophore Cephalosporin, against Gram-Negative Bacteria, Including Carbapenem-Resistant Nonfermenters and Enterobacteriaceae with Defined Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases and Carbapenemases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issac, M.; Flinchum, A.; Spicer, K. Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales-Kentucky, 2013-2020: Challenges and Successes. J. Appalach. Health 2023, 5, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mataseje, L.F.; Abdesselam, K.; Vachon, J.; Mitchel, R.; Bryce, E.; Roscoe, D.; Boyd, D.A.; Embree, J.; Katz, K.; Kibsey, P.; et al. Results from the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program on Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae, 2010 to 2014. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 6787–6794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghi, M.; Pereira, M.F.; Schuenck, R.P. The Presence of Virulent and Multidrug-Resistant Clones of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in Southeastern Brazil. Curr. Microbiol. 2023, 80, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conci Campos, C.; Franco Roriz, N.; Nogueira Espínola, C.; Aguilar Lopes, F.; Tieppo, C.; Freitas Tetila, A.; Volpe Chaves, C.E.; Alexandrino de Oliveira, P.; Rodrigues Chang, M. KPC: An Important Mechanism of Resistance in K. Pneumoniae Isolates from Intensive Care Units in the Midwest Region of Brazil. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2017, 11, 646–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fochat, R.C.; de Lelis Araújo, A.C.; Pereira Júnior, O.D.S.; Silvério, M.S.; de Nassar, A.F.C.; Junqueira, M.d.L.; Silva, M.R.; Garcia, P.G. Prevalence and Molecular Characterization of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales in Patients from a Public Referral Hospital in a Non-Metropolitan Region of Brazil during and Post the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2024, 55, 3873–3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiffer, C.R.V.; Rezende, T.F.T.; Costa-Nobre, D.T.; Marinonio, A.S.S.; Shiguenaga, L.H.; Kulek, D.N.O.; Arend, L.N.V.S.; de Santos, I.C.O.; Sued-Karam, B.R.; Rocha-de-Souza, C.M.; et al. A 7-Year Brazilian National Perspective on Plasmid-Mediated Carbapenem Resistance in Enterobacterales, Pseudomonas Aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter Baumannii Complex and the Impact of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic on Their Occurrence. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 77, S29–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavares, C.P.; Pereira, P.S.; de Andrade Marques, E.; Faria, C., Jr.; da Penha Araújo Herkenhoff de Souza, M.; de Almeida, R.; de Fátima Morais Alves, M.; Asensi, M.D.; D’Alincourt Carvalho-Assef, A.P. Molecular Epidemiology of KPC-2-Producing Enterobacteriaceae (Non-Klebsiella pneumoniae) Isolated from Brazil. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2015, 82, 326–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Tolentino, F.M.; Bueno, M.F.C.; Franscisco, G.R.; de Barcelos, D.D.P.; Lobo, S.M.; Tomaz, F.M.M.B.; da Silva, N.S.; de Andrade, L.N.; Casella, T.; da Darini, A.L.C.; et al. Endemicity of the High-Risk Clone Klebsiella pneumoniae ST340 Coproducing QnrB, CTX-M-15, and KPC-2 in a Brazilian Hospital. Microb. Drug Resist. 2019, 25, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez-Prada, E.D.; Bustos, I.G.; Gamboa-Silva, E.; Josa, D.F.; Mendez, L.; Fuentes, Y.V.; Serrano-Mayorga, C.C.; Baron, O.; Ruiz-Cuartas, A.; Silva, E.; et al. Molecular Characterization and Descriptive Analysis of Carbapenemase-Producing Gram-Negative Rod Infections in Bogota, Colombia. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0171423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo, A.M.; Chen, L.; Cienfuegos, A.V.; Roncancio, G.; Chavda, K.D.; Kreiswirth, B.N.; Jiménez, J.N. A Two-Year Surveillance in Five Colombian Tertiary Care Hospitals Reveals High Frequency of Non-CG258 Clones of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae with Distinct Clinical Characteristics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echegorry, M.; Marchetti, P.; Sanchez, C.; Olivieri, L.; Faccone, D.; Martino, F.; Sarkis Badola, T.; Ceriana, P.; Rapoport, M.; Lucero, C.; et al. National Multicenter Study on the Prevalence of Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in the Post-COVID-19 Era in Argentina: The RECAPT-AR Study. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quesille-Villalobos, A.M.; Solar, C.; Martínez, J.R.W.; Rivas, L.; Quiroz, V.; González, A.M.; Riquelme-Neira, R.; Ugalde, J.A.; Peters, A.; Ortega-Recalde, O.; et al. Multispecies Emergence of Dual blaKPC/NDM Carbapenemase-Producing Enterobacterales Recovered from Invasive Infections in Chile. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2025, 69, e0120524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soria-Segarra, C.; Soria-Segarra, C.; Molina-Matute, M.; Agreda-Orellana, I.; Núñez-Quezada, T.; Cevallos-Apolo, K.; Miranda-Ayala, M.; Salazar-Tamayo, G.; Galarza-Herrera, M.; Vega-Hall, V.; et al. Molecular Epidemiology of Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacilli in Ecuador. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.M.; Salem, S.T.; Hassan, S.I.M.; Hegab, A.S.; Elkholy, Y.S. Molecular Characterization of Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter Baumannii Clinical Isolates from Egyptian Patients. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odewale, G.; Jibola-Shittu, M.Y.; Ojurongbe, O.; Olowe, R.A.; Olowe, O.A. Genotypic Determination of Extended Spectrum β-Lactamases and Carbapenemase Production in Clinical Isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae in Southwest Nigeria. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2023, 15, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ssekatawa, K.; Ntulume, I.; Byarugaba, D.K.; Michniewski, S.; Jameson, E.; Wampande, E.M.; Nakavuma, J. Isolation and Characterization of Novel Lytic Bacteriophages Infecting Carbapenem-Resistant Pathogenic Diarrheagenic and Uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Drug Resist. 2024, 17, 3367–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanheira, M.; Sader, H.S.; Farrell, D.J.; Mendes, R.E.; Jones, R.N. Activity of Ceftaroline-Avibactam Tested against Gram-Negative Organism Populations, Including Strains Expressing One or More β-Lactamases and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Carrying Various Staphylococcal Cassette Chromosome Mec Types. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 4779–4785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estabrook, M.; Muyldermans, A.; Sahm, D.; Pierard, D.; Stone, G.; Utt, E. Epidemiology of Resistance Determinants Identified in Meropenem-Nonsusceptible Enterobacterales Collected as Part of a Global Surveillance Study, 2018 to 2019. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2023, 67, e0140622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazmierczak, K.M.; Biedenbach, D.J.; Hackel, M.; Rabine, S.; de Jonge, B.L.M.; Bouchillon, S.K.; Sahm, D.F.; Bradford, P.A. Global Dissemination of blaKPC into Bacterial Species beyond Klebsiella pneumoniae and In Vitro Susceptibility to Ceftazidime-Avibactam and Aztreonam-Avibactam. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 4490–4500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobrega, D.; Peirano, G.; Matsumura, Y.; Pitout, J.D.D. Molecular Epidemiology of Global Carbapenemase-Producing Citrobacter spp. (2015–2017). Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0414422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanheira, M.; Deshpande, L.M.; Mendes, R.E.; Canton, R.; Sader, H.S.; Jones, R.N. Variations in the Occurrence of Resistance Phenotypes and Carbapenemase Genes Among Enterobacteriaceae Isolates in 20 Years of the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2019, 6, S23–S33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, D.; Peirano, G.; Lascols, C.; Lloyd, T.; Church, D.L.; Pitout, J.D.D. Laboratory Detection of Enterobacteriaceae That Produce Carbapenemases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 3877–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gales, A.C.; Stone, G.; Sahm, D.F.; Wise, M.G.; Utt, E. Incidence of ESBLs and Carbapenemases among Enterobacterales and Carbapenemases in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Isolates Collected Globally: Results from ATLAS 2017–2019. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2023, 78, 1606–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawser, S.P.; Bouchillon, S.K.; Hoban, D.J.; Hackel, M.; Johnson, J.L.; Badal, R.E. Klebsiellapneumoniae Isolates Possessing KPC Beta-Lactamase in Israel, Puerto Rico, Colombia and Greece. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2009, 34, 384–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlowsky, J.A.; Wise, M.G.; Hackel, M.A.; Pevear, D.C.; Moeck, G.; Sahm, D.F. Ceftibuten-Ledaborbactam Activity against Multidrug-Resistant and Extended-Spectrum-β-Lactamase-Positive Clinical Isolates of Enterobacterales from a 2018–2020 Global Surveillance Collection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e0093422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazmierczak, K.M.; Karlowsky, J.A.; de Jonge, B.L.M.; Stone, G.G.; Sahm, D.F. Epidemiology of Carbapenem Resistance Determinants Identified in Meropenem-Nonsusceptible Enterobacterales Collected as Part of a Global Surveillance Program, 2012 to 2017. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e0200020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazmierczak, K.M.; Tsuji, M.; Wise, M.G.; Hackel, M.; Yamano, Y.; Echols, R.; Sahm, D.F. In Vitro Activity of Cefiderocol, a Siderophore Cephalosporin, against a Recent Collection of Clinically Relevant Carbapenem-Non-Susceptible Gram-Negative Bacilli, Including Serine Carbapenemase- and Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Isolates (SIDERO-WT-2014 Study). Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2019, 53, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascols, C.; Hackel, M.; Hujer, A.M.; Marshall, S.H.; Bouchillon, S.K.; Hoban, D.J.; Hawser, S.P.; Badal, R.E.; Bonomo, R.A. Using Nucleic Acid Microarrays to Perform Molecular Epidemiology and Detect Novel β-Lactamases: A Snapshot of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases throughout the World. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 1632–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wise, M.G.; Karlowsky, J.A.; Mohamed, N.; Kamat, S.; Sahm, D.F. In Vitro Activity of Aztreonam-Avibactam against Enterobacterales Isolates Collected in Latin America, Africa/Middle East, Asia, and Eurasia for the ATLAS Global Surveillance Program in 2019–2021. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2023, 42, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haji, S.H.; Aka, S.T.H.; Ali, F.A. Prevalence and Characterisation of Carbapenemase Encoding Genes in Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacilli. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0259005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigit, H.; Queenan, A.M.; Anderson, G.J.; Domenech-Sanchez, A.; Biddle, J.W.; Steward, C.D.; Alberti, S.; Bush, K.; Tenover, F.C. Novel Carbapenem-Hydrolyzing β-Lactamase, KPC-1, from a Carbapenem-Resistant Strain of Klebsiella Pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther-Rasmussen, J.; Høiby, N. Class A Carbapenemases. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007, 60, 470–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Bij, A.K.; Pitout, J.D.D. The Role of International Travel in the Worldwide Spread of Multiresistant Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 2090–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoesser, N.; Phan, H.T.T.; Seale, A.C.; Aiken, Z.; Thomas, S.; Smith, M.; Wyllie, D.; George, R.; Sebra, R.; Mathers, A.J.; et al. Genomic Epidemiology of Complex, Multispecies, Plasmid-Borne blaKPC Carbapenemase in Enterobacterales in the United Kingdom from 2009 to 2014. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, S.; Chavda, K.D.; Wei, J.; Zou, C.; Marshall, S.H.; Dhawan, P.; Wang, D.; Bonomo, R.A.; Kreiswirth, B.N.; Chen, L. A Ceftazidime-Avibactam-Resistant and Carbapenem-Susceptible Klebsiella pneumoniae Strain Harboring blaKPC-14 Isolated in New York City. mSphere 2020, 5, e00775-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-R.; Lee, J.H.; Park, K.S.; Kim, Y.B.; Jeong, B.C.; Lee, S.H. Global Dissemination of Carbapenemase-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae: Epidemiology, Genetic Context, Treatment Options, and Detection Methods. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, J.A.; Melano, R.; Cárdenas, P.A.; Trueba, G. Mobile Genetic Elements Associated with Carbapenemase Genes in South American Enterobacterales. Braz. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 24, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcillán-Barcia, M.P.; Redondo-Salvo, S.; de la Cruz, F. Plasmid Classifications. Plasmid 2023, 126, 102684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman-Otazo, J.; Joffré, E.; Agramont, J.; Mamani, N.; Jutkina, J.; Boulund, F.; Hu, Y.O.O.; Jumilla-Lorenz, D.; Farewell, A.; Larsson, D.G.J.; et al. Conjugative Transfer of Multi-Drug Resistance IncN Plasmids from Environmental Waterborne Bacteria to Escherichia coli. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 997849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochan, T.J.; Nozick, S.H.; Valdes, A.; Mitra, S.D.; Cheung, B.H.; Lebrun-Corbin, M.; Medernach, R.L.; Vessely, M.B.; Mills, J.O.; Axline, C.M.R.; et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae Clinical Isolates with Features of Both Multidrug-Resistance and Hypervirulence Have Unexpectedly Low Virulence. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellera, F.P.; Lincopan, N.; Fuentes-Castillo, D.; Stehling, E.G.; Furlan, J.P.R. Rapid Evolution of Pan-β-Lactam Resistance in Enterobacterales Co-Producing KPC and NDM: Insights from Global Genomic Analysis after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Lancet Microbe 2024, 5, e412–e413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsioutis, C.; Eichel, V.M.; Mutters, N.T. Transmission of Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase (KPC)-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae: The Role of Infection Control. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, i4–i11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Tan, R.; Sun, J.; Li, L.; Huang, J.; Wu, J.; Gu, Q.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Infection-Prevention and Control Interventions to Reduce Colonisation and Infection of Intensive Care Unit-Acquired Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella Pneumoniae: A 4-Year Quasi-Experimental before-and-after Study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2019, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelesidis, T.; Falagas, M.E. The Safety of Polymyxin Antibiotics. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2015, 14, 1687–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Wang, Y.-L.; Du, S.; Chen, L.; Long, L.-H.; Wu, Y. Efficacy and Safety of Tigecycline for Patients with Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia. Chemotherapy 2016, 61, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, M.S.; Sfeir, M.M.; Calfee, D.P.; Satlin, M.J. Cost-Effectiveness of Ceftazidime-Avibactam for Treatment of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae Bacteremia and Pneumonia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobson, C.A.; Pierrat, G.; Tenaillon, O.; Bonacorsi, S.; Bercot, B.; Jaouen, E.; Jacquier, H.; Birgy, A. Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase Variants Resistant to Ceftazidime-Avibactam: An Evolutionary Overview. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e0044722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shields, R.K.; Chen, L.; Cheng, S.; Chavda, K.D.; Press, E.G.; Snyder, A.; Pandey, R.; Doi, Y.; Kreiswirth, B.N.; Nguyen, M.H.; et al. Emergence of Ceftazidime-Avibactam Resistance Due to Plasmid-Borne Bla(KPC-3) Mutations during Treatment of Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Infections. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaibani, P.; Campoli, C.; Lewis, R.E.; Volpe, S.L.; Scaltriti, E.; Giannella, M.; Pongolini, S.; Berlingeri, A.; Cristini, F.; Bartoletti, M.; et al. In Vivo Evolution of Resistant Subpopulations of KPC-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae during Ceftazidime/Avibactam Treatment. J. Antimicrob Chemother. 2018, 73, 1525–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamma, P.D.; Heil, E.L.; Justo, J.A.; Mathers, A.J.; Satlin, M.J.; Bonomo, R.A. Infectious Diseases Society of America 2024 Guidance on the Treatment of Antimicrobial-Resistant Gram-Negative Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, ciae403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Author, Year [ref.] * | Continent | Country | Isolation Period | Population, n/N (%) | Sources of Isolation (n) | Species (n) | KPC Detection, n/N (%) | Types of KPC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hassan, 2021 [121] | Africa | Egypt | 12/2018–12/2019 | Clinical isolates, 154/206 (75) ICU | Wound swabs (77), respiratory secretions (56), blood (37), urine (27), and other (9) | Carbapenem-resistant A. baumannii | 22/206 (11) | blaKPC |

| Odewale, 2023 [122] | Africa | Nigeria | 2/2018–8/2019 | Clinical isolates | NR | K. pneumoniae | 17/128 (13) | blaKPC |

| Ssekatawa, 2021 [123] | Africa | Uganda | 1/2019–12/2019 | Clinical isolates | Urine (128), pus swabs (48), blood (23), rectal swabs (16), vaginal swabs (7), tracheal aspirate (3), and sputum (2) | K. pneumoniae | 18/227 (8) | blaKPC-type |

| Fang, 2019 [20] | Asia | China | 1/2015–1/2017 | Inpatient, 41/47, (87) colonization, 6/47 (13) infection | Respiratory (20), urine (12), blood (6), ascites (3), bile (2), skin (1), and other (3) | CRE; K. pneumoniae (35), E. cloacae (4), Citrobacter freundii (3), E. coli (3), and K. oxytoca (2) | 38/47 (81) | blaKPC-2 |

| Ge, 2024 [21] | Asia | China | 2021–2022 | Inpatient | BAL, blood, sputum, and urine | CRKP; K. pneumoniae | 30/31 (97) | blaKPC-2 |

| Han, 2020 [22] | Asia | China | 1/2016 –12/2018 | Inpatient, 498/935 (53) children | Ascites, bile, blood, catheter, drainage, other aseptic body fluids, pus, sputum, and urine | CRE; K. pneumoniae (709), E. coli (149), E. cloacae (36), Citrobacter freundii (14), Serratia marcescens (8), E. aerogenes (7), K. oxytoca (7), Morganella morganii (3), Proteus vulgaris (1), and Providencia rettgeri (1) | 482/935 (52); 307/935 (70) in adults, 175/935 (35) in children | blaKPC |

| Hu, 2020 [23] | Asia | China | 2008–2018 | Clinical isolates | NR | CRKP; K. pneumoniae | 504/534 (94) | blaKPC-2 |

| Jin, 2022 [24] | Asia | China | 1/2019–12/2021 | Inpatient, children | Sputum, urine, blood, catheter, BAL, gastric fluid, and others | K. pneumoniae | 21/34 (62) | blaKPC-2 |

| Jing, 2022 [25] | Asia | China | 07/2019–10/2019 | NR | Respiratory tract (129), blood (45), urine (17), wounds (8), ascitic fluid (6), pleural effusion (5), cerebrospinal fluid (4), and other (24) | K. pneumoniae (184), E. cloacae (11), K. oxytoca (6), Citrobacter freundii (5), K. aerogenes (2), and Serratia marcescens (1) | 175/238 (74) | blaKPC-2 |

| Kang, 2020 [26] | Asia | China | 1/2016–12/2016 | ICU | Blood, CSF, lower respiratory tract, urine, and wounds | CRKP; K. pneumoniae | 120/128 (94) | blaKPC-2 |

| Li, 2021 [27] | Asia | China | 2015–2018 | NR | Lower respiratory tract (249), urine (33), secretion (25), blood (14), catheter (13), puncture fluid (7), pleural fluid (7), drainage fluid (4), ascitic fluid (3), cerebral spinal fluid (2), pus (2), and bile (1) | K. pneumoniae (350), E. coli (26), E. cloacae (15), and other (8) | 119/399 (30) | blaKPC-2 |

| Liang, 2024 [28] | Asia | China | 1/2013–12/2022 | Inpatient | Bloodstream infections | CRE; K. pneumoniae, E. coli, E. cloacae, and K. oxytoca, Salmonella spp. | 8/35 (23) | blaKPC |

| Liao, 2023 [29] | Asia | China | 01/2018–02/2021 | Clinical isolates | Sputum (17), bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (8), urine (7), blood (3), secretion (3), and others (4) | K. pneumoniae | 35/42 (83) | blaKPC-2 |

| Liu, 2021 [30] | Asia | China | 2004–2018 | Clinical isolates | NR | E. cloacae complex | 14/113 (12) | blaKPC-2 |

| Ma, 2024 [31] | Asia | China | 1/2021–12/2021 | Inpatient, children | Sputum (63), blood (11), urine (10), BAL (9), ascites (5), CSF (3), joint fluid (1), hydrothorax (1), and other (2) | CRKP; K. pneumoniae | 93/108 (86) | blaKPC |

| Peng, 2022 [32] | Asia | China | 1/2015–12/2018 | Inpatient, 36/89 (40) ICU | Sputum (86), urine (31), blood (13), lung tissue (9), and bile (7) | CRE; K. pneumoniae (89), E. coli (28), E. cloacae (20), Citrobacter freundii (5), K. aerogenes (3), and Cronobacter sakazakii (1) | 73/146 (50) | blaKPC-2 |

| Shen, 2023 [33] | Asia | China | 01/2018–12/2020 | Clinical isolates | NR | K. pneumoniae | 23/94 (24) | blaKPC |

| Shi, 2024 [34] | Asia | China | 2018–2019 | Clinical isolates | NR | CRKP; K. pneumoniae (708) | 563/708 (80) | blaKPC-2 |

| Tian, 2018 [35] | Asia | China | 1/2016–12/2017 | Inpatient, children | NR | CRKP; K. pneumoniae | 30/169 (18) | blaKPC-2 |

| Tian, 2020 [36] | Asia | China | 2002–2017 | Clinical isolates | Urine (18), blood (16), drainage (11), and other (13) | E. coli | 13/58 (22) | blaKPC-2 |

| Wang, 2018 [37] | Asia | China | 1/2012 –12/2016 | Clinical isolates | Respiratory tract (858), blood (304), urine (303), abdominal fluid (117), and other (219) | CRE; K. pneumoniae (1201), E. coli (282), E. cloacae (179), Citrobacter freundii (44), K. oxytoca (29), Serratia marcescens (28), E. aerogenes (24), Raoultella ornithinolytica (6), Citrobacter braakii (3), Citrobacter koseri (3), and Raoultella planticola (2) | 961/1801 (53) | blaKPC-2 |

| Wang, 2020 [39] | Asia | China | 10/2016–3/2019 | Inpatient | Sputum (12), drainage fluid (4), blood (3), wound (2), urine/urinary catheter (7), and bronchial perfusate (1) | CRKP; K. pneumoniae | 12/30 (40) | blaKPC |

| Wang, 2022 [38] | Asia | China | 3/2018–6/2018 | Inpatient | Sputum (18), blood (16), pus (6), ascites (2), CSF (1), bile (1), and secretions (1) | CRKP; K. pneumoniae | 42/45 (93) | blaKPC-2 |

| Wei, 2022 [40] | Asia | China | 1/2020–12/2020 | ICU | Blood, pus, puncture fluid, respiratory tract, and urine | CRKP; K. pneumoniae | 79/80 (99) | blaKPC-2 |

| Wu, 2024 [41] | Asia | China | 2021 | Inpatient | Blood, CNS, gastrointestinal tract, genital tract, peritoneum, respiratory tract, skin/soft tissue, and urinary tract | Carbapenem-resistant: A. baumannii, Enterobacterales, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and P. aeruginosa | 203/1257 (16) | blaKPC |

| Yan, 2021 [42] | Asia | China | 2018–2019 | Clinical isolates | Sputum (142), blood (82), urine (21), ascites (11), wound (9), CSF (5), and other (35) | CRE; K. pneumoniae, E. coli, E. cloacae, Citrobacter freundii, K. oxytoca, Providencia rettgeri, K. aerogenes, and Serratia marcescens | 215/305 (70) | blaKPC |

| Yang, 2013 [43] | Asia | China | 2/2009–11/2011 | Inpatient, ICU | Sputum (25), blood (8), urine (7), venous cannula (3), drainage fluid (3), and bile (2) | K. pneumoniae | 2/2009–11/2011: 48/1636 (3) 12/2012–6/2012: 41/351 (12) | blaKPC-2 |

| Zhang, 2021 [44] | Asia | China | 4/2018–7/2019 | Inpatient, 102/133 (77) ICU | Sputum (81), bile (12), urine (12), blood (8), and CSF and BAL (7) | CRKP; K. pneumoniae | 133/133 (100) | blaKPC-2 |

| Patil, 2023 [63] | Asia | India | 1/2020–12/2021 | Inpatients, outpatient | Blood, urine, wound, sputum, and CSF | K. pneumoniae | 13/60 (22) | blaKPC |

| Darabi, 2019 [64] | Asia | Iran | 12/2013–9/2016 | Inpatient, 107/182 (59) outpatient | Urine (137) and sputum (26), wounds (10), blood (8), and stool (1) | K. pneumoniae | 7/182 (4) | blaKPC |

| Haji, 2021 [137] | Asia | Iraq | 2019–2020 | Clinical isolates, inpatient and outpatient | Urine, sputum, swabs, and blood | E. coli, A. baumannii, and Achromobacter dentrificans | 4/53 (7) | blaKPC |

| Adler, 2011 [46] | Asia | Israel | 8/2008–4/2009 | Inpatient | Rectal swabs | CRE; K. pneumoniae, K. oxytoca, and E. aerogenes | 32/33 (97) | blaKPC |

| Adler, 2015 [45] | Asia | Israel | 1/2009–6/2012 | Inpatient | Surveillance cultures (76) and blood (12) | E. coli | 88/88 (100) | blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3 |

| Ben-David, 2015 [47] | Asia | Israel | 1/2006–5/2007 | Inpatient | Blood and urine | CRKP; K. pneumoniae | 120/120 (100) | blaKPC-3 |

| Hussein, 2022 [48] | Asia | Israel | 1/2005–12/2020 | Inpatient | Rectal swabs | CPE; Citrobacter spp., E. coli, E. cloacae, K. oxytoca, K. pneumoniae, Morganella spp., Proteus spp., Providencia spp., and Raoultella spp. | 2014: 89/95 (94) 2015: 100/109 (92) 2016: 51/59 (84) 2017: 58/65 (88) 2018: 58/88 (66) 2019: 71/141 (51) 2020: 75/134 (56) 2014–2020: 502/691 (73) | blaKPC |

| Manandhar, 2020 [49] | Asia | Nepal | 6/2012–12/2018 | Inpatient, 295/2153 (14) children | NR | E. coli (719), Klebsiella spp. (532), and Enterobacter spp. (520), and A. baumannii (383) | E. coli: 0/719 (0) Klebsiella spp.: 22/532 (4) Enterobacter: 201/337 (60) a A. baumannii: not tested | blaKPC |

| Sah, 2021 [50] | Asia | Nepal | 1/2016–12/2016 | Inpatient, ICU, children, neonates | Blood | A. baumannii complex, E. coli, E, aerogenes, and K. pneumoniae | 8/50 (16) | blaKPC |

| Takahashi, 2021 [51] | Asia | Nepal | 10/2018–1/2020 | Hospital samples | NR | P. aeruginosa | 4/43 | blaKPC-2 |

| AlAmri, 2019 [62] | Asia | Saudi Arabia | 9/2017–5/2018 | Clinical isolates | Respiratory tract (41), wound swabs (18), rectal swabs (13), blood (10), urine (6), and other (15) | A. baumannii | 103/103 (100) | blaKPC-like |

| Ling, 2015 [52] | Asia | Singapore | 1/2011–12/2013 | Inpatient | Stool, urine, wound, blood, sputum, bile, catheter, peritoneal fluid, mephrostomy fluid, tracheal aspirate, and ulcer | CRE; K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and E. cloacae complex | 107/268 (40) | blaKPC |

| Teo, 2014 [53] | Asia | Singapore | 9/2010–5/2013 | Clinical isolates | NR | CRE; E. coli, Klebsiella spp., Citrobacter spp., and Enterobacter spp. | 31/400 (8) | blaKPC-type |

| Teo, 2022 [54] | Asia | Singapore | 2009–2020 | Inpatient | NR | CRKP; K. pneumoniae sensu stricto (500), K. quasipneumoniae subsp. similipneumoniae (55), K. quasipneumoniae subsp. quasipneumoniae (55), and K. variicola subsp. variicola (9) | 235/575 (41) | blaKPC |

| Lim, 2024 [1] | Asia | South Korea | 2018–2022 | Clinical isolates | NR | CPE; K. pneumoniae, E. coli, Enterobacter spp., Citrobacter freundii, K. oxytoca, Serratia marcescens, Citrobacter koseri, Raoultella ornitholytica, Providencia rettgeri, Proteus spp., and Morganella morganii | 47,313/63,513 (74) | blaKPC |

| Yoo, 2023 [59] | Asia | South Korea | 01/2016–12/2021 | Inpatients from ICU | NR | K. pneumoniae (253), E. cloacae complex (44), E. coli (15), and others (15) | 164/327 (50) | blaKPC |

| Chiu, 2013 [55] | Asia | Taiwan | 2010–2012 | Clinical isolates | NR | CRKP; K. pneumoniae | 41/347 (12) | blaKPC-2 |

| Huang, 2023 [56] | Asia | Taiwan | 2013–2021 | NR | Urine (68), blood (50), sputum (37), skin/pus/wound (14), body fluids (5), and catheter tip (1) | CPE; K. pneumoniae (79), E. coli (56), E. cloacae complex (44), Citrobacter freundii (9), K. oxytoca (6), and K. aerogenes (1) | 38/195 (19) | blaKPC |

| Lee, 2021 [57] | Asia | Taiwan | 2017–2020 | Inpatient | NR | CRE; K. pneumoniae (175), E. coli (26) | 2017: 64/83 (77) 2018: 27/36 (75) 2019: 37/43 (85) 2020: 32/39 (82) 2017–2020: 69/201 (34) | blaKPC |

| Falco, 2016 [65] | Asia | Venezuela | 4/2014–7/2014 | Inpatient, children, 2/19 (11) ICU | Blood (15), bronchial secretion (2) catheter (1), and lesion secretion (1) | CRKP; K. pneumoniae | 19/19 (100) | blaKPC-2 |

| Berglund, 2019 [60] | Asia | Vietnam | 2/2015–9/2015 | Inpatient | Tracheal fluid, nasopharynx, blood, and other | K. pneumoniae | 57/57 (100) | blaKPC-2 |

| Linh, 2021 [61] | Asia | Vietnam | 2010–2015 | Inpatient | Bronchial fluid (92), blood (18), sputum (6), urine (4), pleural fluid (1), abdominal fluid (1) | CRE; K. pneumoniae (305), E. coli (186), Klebsiella spp. (54), Enterobacter spp. (29), and Citrobacter spp. (25) | 122/599 (20) b | blaKPC-2, blaKPC-12 |

| Miriagou, 2010 [13] | Asia/Europe | Russia | 1/2020–12/2021 | Inpatient | Blood, cerebrospinal fluid, urine, BAL, endotracheal aspirate, biopsies, and wound swabs | K. pneumoniae (2503) and E. coli (2055) | 410/4558 (9) | blaKPC-3 |

| Yürek, 2023 [66] | Asia/Europe | Turkey | 12/2020–3/2021 | Inpatient, outpatient | Urine (27), blood (6), respiratory tract (6), abscess or wound (3), and other (3) | K. pneumoniae | 5/35 (14) | blaKPC c |

| David, 2019 [93] | Europe | 31 countries d | 11/2013–4/2014 | NR | NR | K. pneumoniae spp. | 311/1649 (18) | blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3, blaKPC-12 |

| Grundmann, 2017 [95] | Europe | Albania, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Kosovo, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Montenegro, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Macedonia, Turkey, the UK—England and Northern Ireland, and the UK—Scotland | 11/2013–4/2014 | Inpatient | All clinical specimens were accepted, except for stool and surveillance screening samples | K. pneumoniae (850), E. coli (77) | 393/927 (42) | blaKPC |

| Hoenigl, 2012 [81] | Europe | Austria | 10/2010–2/2011 | Inpatient | NR | K. oxytoca | 31/31 (100) | blaKPC |

| Kazmierczak, 2020 [94] | Europe | Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, the UK, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Turkey, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Russia | 2013–2017 | NR | Lower respiratory tract, skin and soft tissue, urinary tract, intra-abdominal, bloodstream, or other infections | CRE; K. pneumoniae, E. cloacae, and E. coli | 570/1231 | blaKPC |

| De Laveleye, 2017 [82] | Europe | Belgium | 1/2013–12/2014 | NR | NR | E. coli and K. pneumoniae | 2013: 13/35 (37) 2014: 25/35 (71) | blaKPC |

| Dobreva, 2022 [83] | Europe | Bulgaria | 2014–2018 | NR | Urine (4), blood (3), wound (2), cerebrospinal fluid (1), tracheobronchial aspirate (1), and rectal swab (1) | K. pneumoniae | 12/12 (100) | blaKPC-2 |

| Hammerum, 2020 [84] | Europe | Denmark | 1/2014–6/2018 | Clinical isolates | NR | K. pneumoniae, Klebsiella quasipneumoniae, and Klebsiella variicola | 8/103 (8) | blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3 |

| Räisänen, 2020 [85] | Europe | Finland | 2012–2018 | Clinical isolates | Urine, wound swabs, blood, respiratory tract | CPE; K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and Citrobacter freundii, E. cloacae | 71/231 (31) | blaKPC-like |

| Carbonne, 2010 [86] | Europe | France | 9/2009–10/2009 | Inpatient, 4/13 (31) infection, 9/13 (69) colonization c | Bile, blood, bronchial aspirate, and rectal swab | K. pneumoniae | 13/295 (4) | blaKPC-2 |

| Bonnin, 2024 [92] | Europe | Germany, Belgium, England, Austria, Netherlands, Poland, and Czech Republic | 1/2013–3/2021 | NR | NR | Carbapenemase-producing Morganella morganii | 26/247 (11) | blaKPC-2 |

| Kontopidou, 2014 [68] | Europe | Greece | 9/2009–6/2010 | ICU | NR | CPKP; K. pneumoniae | 52/82 (63) | blaKPC |

| Pournaras, 2013 [69] | Europe | Greece | 9/2010–2/2012 | Inpatient | Rectal swab | CPE; K. pneumoniae, E. coli | 56/97 (58) | blaKPC |

| Sorovou, 2023 [70] | Europe | Greece | 1/2019–12/2022 | Inpatient, 26/212 (12) ICU | Urine (154), rectal swab (12), BAL (11), wound swabs (8), sputum (7), central venous catheter (5), and other (15) | K. pneumoniae | 2019: 10/51 (20) 2020: 8/42 (19) 2021: 9/54 (17) 2022: 38/65 (58) 2019–2022: 65/212 (31) | blaKPC |

| Zarras, 2022 [71] | Europe | Greece | 3/2018–3/2021 | ICU, 34/150 (23) pediatric/neonatal | Blood, bronchial secretions, rectal swabs, trauma, and urine e | CRKP; K. pneumoniae | 56/150 (37), 24/34 (71) in children and neonates | blaKPC |

| Budia-Silva, 2024 [11] | Europe | Greece, Italy, Romania, Serbia, Spain, and Turkey | 2016–2018 | Inpatient | Blood (334), urine (213), and other (140) | CRKP; K. pneumoniae | 384/683 (56) | blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3, blaKPC-36 |

| Buzgó, 2025 [79] | Europe | Hungary | 3/2021–4/2023 | Inpatient | NR | K. pneumoniae | 53/420 (13) | blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3 |

| Toth, 2010 [80] | Europe | Hungary | 9/2008–4/2009 | Inpatient | Wound (2), lower respiratory tract (2), upper respiratory tract (2), stool (2), and central venous catheter (1) | K. pneumoniae | 9/9 (100) | blaKPC-2 |

| Morris, 2012 [87] | Europe | Ireland | 2011 | Inpatient | Blood, central venous catheter, rectal swab, and urine | CRKP; K. pneumoniae | 19/19 (100) | blaKPC-2 |

| Agodi, 2011 [72] | Europe | Italy | 3/2009–5/2009 | ICU | Sputum (7), blood (6), urine (5), tonsillar swab (3), catheter tip (2), and peritoneal fluid (1) | CRKP; K. pneumoniae | 24/24 (100) | blaKPC-3 |

| Orena, 2024 [73] | Europe | Italy | 1/2024–6/2024 | Inpatient | Rectal swabs | CRE; E. coli, E. cloacae, K. oxytoca, and K. pneumoniae | 30/118 (25) | blaKPC |

| Piazza, 2024 [74] | Europe | Italy | 10/2021–3/2022 | Inpatient, infection, colonization | Blood (14), rectal swabs (3), respiratory tract (3), urine (1) | Ceftazidime-resistant; K. pneumoniae | 21/21 (100) | blaKPC |

| Santino, 2013 [75] | Europe | Italy | 1/2012–6/2012 | Clinical isolates | Urine (5), wound (3), sputum (3), BAL (1), skin swab (l), blood (1), and pharyngeal swab (1) | K. pneumoniae | 15/15 (100) | blaKPC-3 |

| Jamin, 2024 [88] | Europe | Netherlands | 2011–2023 | Clinical isolates | NR | K. pneumoniae | 107/2985 (4) | blaKPC-3 |

| Samuelsen, 2017 [89] | Europe | Norway | 2007–2014 | Inpatient, traveling abroad | Urine and fecal screening | CPE; K. pneumoniae and E. cloacae | 20/59 (34) | blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3 |

| Guzek, 2019 [76] | Europe | Poland | 1/2009–12/2016 | Inpatients | Urine (46), cloacal swabs for fecal carriage (43), blood (11), wounds (9), bronchial tree aspirates collected via an endotracheal tube (8), abscesses (3), and fluid collected from the abdominal cavity (2) | K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and C. freundii | 73/122 (60) | blaKPC |

| Kuch, 2020 [77] | Europe | Poland | 1/2000–1/2017 | NR | Urine, blood, and other clinical specimens (bronchial secretions, cerebrospinal fluid, peritoneal fluid, pleural fluid, pus, skin lesions, sputum, and wounds) | K. pneumoniae, K. oxytoca, P. mirabilis, P. penneri, P. vulgaris, C. freundii, C. braakii, E. cloacae, E. aerogenes, E. amnigenus, S. marcescens, M. morganii, and P. rettgeri | 40/400 (10) | blaKPC |

| Mrowiec, 2019 [78] | Europe | Poland | 2008–2015 | Inpatient | Children: stool (69) and perianal swabs (12); adults: respiratory system (39), urine (23), and blood (10) | K. pneumoniae | 14/170 (8) | blaKPC |

| Baicus, 2018 [90] | Europe | Romania | 2016 | Inpatient, ICU | Lower respiratory tract (20), urine (30), blood (4), peritoneum (1), wound (5), and sputum (1) | K. pneumoniae | 6/20 (30) | blaKPC |

| Gracia-Ahufinger, 2023 [91] | Europe | Spain | 1/2014–12/2018 | Inpatient | NR | CPE; K. pneumoniae, E. cloacae complex, E. coli, and K. aerogenes | 313/2280 (14) | blaKPC |

| Kazmierczak, 2016 [126] | Global | 40 countries | 2012–2014 | Inpatient, 195/586 (33) ICU f | Respiratory tract (189), urinary tract (137), skin/soft tissue (132), and wounds (71) f | CRE; Enterobacterales (38,266) and P. aeruginosa (8010) | 586/46,276 (1) | blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3, blaKPC-9, blaKPC-12, blaKPC-18 |

| Nobrega, 2023 [127] | Global | 56 countries | 2015–2017 | NR | NR | Citrobacter freundii (51), Citrobacter portucalensis (20), Citrobacter koseri (10), Citrobacter farmeri (3), Citrobacter amalonaticus (1), and Citrobacter braakii (1) | 29/91 (32) | blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3 |

| Estabrook, 2023 [125] | Global | NR | 2018–2019 | NR | NR | Meropenem-resistant; K. pneumoniae, E. cloacae, E. coli, Providencia spp., Serratia marcescens, Klebsiella spp., Citrobacter spp., Enterobacter spp., Proteus spp., and Morganella morganii | 568/2228 (26) | blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3, blaKPC-4, blaKPC-6, blaKPC-31, blaKPC-46, blaKPC-66 |

| Castanheira, 2012 [124] | Global | NR g | 1999–2008 | Inpatient | NR | CPE; E. coli and Klebsiella spp. | 56/69 (81) | blaKPC |

| Issac, 2023 [108] | North America | Canada | 2013–2020 | Inpatient | Urine (917), axilla/groin/rectum (343), wounds (197), respiratory tract (163), blood (84), other (91), and unknown (10) | CRE; K. pneumoniae (542), E. cloacae (508), E. coli (238), others (512), and unknown (5) | 406/1805 (22) | blaKPC |

| Mataseje, 2016 [109] | North America | Canada | 1/2010–12/2014 | Inpatient, outpatient | Stool or rectal swab, urine, sputum, blood, skin or soft tissue, surgical site, and other | CPE; K. pneumoniae, Enterobacter spp., Serratia spp., Citrobacter spp., K. oxytoca, Morganella morganii, Providencia rettgeri, Pantoea spp., and Kluyvera spp. | 169/261 (65) | blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3, blaKPC-4 |

| Bradford, 2004 [96] | North America | USA | 11/1997–7/2001 | Inpatient | Urine (9), sputum (8), blood (1), and miscellaneous sources (3) h | CPE; K. pneumoniae (18) and K. oxytoca (1) | 19/19 (100) | blaKPC-2 |

| Castanheira, 2017 [97] | North America | USA | 2012–2015 | Inpatient | Pneumonia, urinary tract infections, skin/soft tissue infections, bloodstream infections, and intra-abdominal infections | CRE; K. pneumoniae, E. cloacae species complex, E. coli, K. oxytoca, Serratia marcescens, Citrobacter freundii, and E. aerogenes | 456/525 (87) | blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3, blaKPC-4, blaKPC-17 i |

| Endimiani, 2009 [98] | North America | USA | 3/2008–4/2008 | Inpatient | Blood, respiratory tract, and urine | K. pneumoniae | 10/241 (4) (total), 10/10 (100) (CRKP) | blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3 |

| Fitzpatrick, 2022 [99] | North America | USA | 1/2013–12/2018 | Inpatient, outpatient | Urine (1163), respiratory tract (235), blood (189), rectal (28), and other (290) | Carbapenemase-producing CRE; E. coli, K. pneumoniae, K. oxytoca, and Enterobacter spp. | 914/1047 (87) | blaKPC |

| Gomez-Simmonds, 2021 [100] | North America | USA | 3/2020–4/2020 | Inpatient | Respiratory tract (14), blood (5), and urine (1) | CPE; K. pneumoniae | 27/31 (87) | blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3 |

| Jacobs, 2019 [107] | North America | USA | NR | NR | NR | K. pneumoniae (794), E. coli (35), Enterobacter spp. (4), and Citrobacter freundii (1) | 737/834 (88) | blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3, blaKPC-4, blaKPC-4-like |

| Kaiser, 2013 [101] | North America | USA | 2007–2009 | Inpatient | Blood, skin and soft tissue, respiratory tract, urinary tract | K. pneumoniae | 113/2049 (6) | blaKPC |

| Karlsson, 2022 [106] | North America | USA | 2011–2015 | Inpatient | Urine (349), blood (58), and other normally sterile sites (14) | CPE; K. pneumoniae (265), E. cloacae complex (77), E. coli (50), K. aerogenes (26), and K. oxytoca (3) | 299/307 (97) | blaKPC |

| Logan, 2019 [102] | North America | USA | 1/2008–12/2014 | Inpatient, children | Urine (9), blood (9), respiratory tract (8), and other (10) | K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and E. cloacae | 18/36 (50) | blaKPC |

| Precit, 2020 [103] | North America | USA | 10/2010–12/2017 | Clinical isolates | Urine (45), bronchial wash or sputum (7), wound (6), blood (3), stool or rectal swab (5), and other (7) | E. coli and Klebsiella spp. | 35/74 (47) | blaKPC |

| Shortridge, 2023 [104] | North America | USA | 2016–2020 | Inpatient | Bloodstream infections, pneumonia, and urinary tract infections | CRE; E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and E. cloacae | 184/222 (83) | blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3, blaKPC-4, blaKPC-6 |

| van Duin, 2020 [105] | North America | USA | 4/2016–8/2017 | Inpatient | Urine (404), respiratory tract (268), blood (130), wound (130), intra-abdominal (58), and other (50) | K. pneumoniae, Enterobacter spp., E. coli, non-K. pneumoniae Klebsiella spp., and other | 573/1040 (55) | blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3, blaKPC-4, blaKPC-6, blaKPC-8, blaKPC-18 |

| Echegorry, 2024 [118] | South America | Argentina | 11/2021 | Clinical isolates | Urine, blood, respiratory tract, abdominal tract, and others | K. pneumoniae (628), Morganellaceae (57), Enterobacter cloacae complex (51), E. coli (38), and other (47) j | 327/821 (40) | blaKPC |

| Borghi, 2023 [110] | South America | Brazil | 4/2015–11/2015 | Inpatient | Blood, bone fragment, catheter, nasal swab, rectal swab, secretions, tracheal aspirate, urine, and wound swab | CRKP; K. pneumoniae | 40/40 (100) | blaKPC |

| Campos, 2017 [111] | South America | Brazil | 3/2013–3/2014 | ICU | Urine, swab surveillance, tracheal aspirate, blood, surgical wound, catheter tip, biological fluids, CSF, and skin biopsy | K. pneumoniae | 149/165 (90) | blaKPC |

| Fochat, 2024 [112] | South America | Brazil | 1/2020–8/2023 | Inpatient, ICU | NR | CRE; K. pneumoniae, Serratia marcescens, E. cloacae, K. aerogenes, and E. coli | 9/46 (20) | blaKPC |

| Kiffer, 2023 [113] | South America | Brazil | 2015–2022 | Inpatient | NR | Enterobacterales, P. aeruginosa, and A. baumannii | Enterobacterales: 41,282/60,205 (68) P. aeruginosa: 1065/12,625 (8) A. baumannii: 52/10,452 (0.5) | blaKPC |

| Tavares, 2015 [114] | South America | Brazil | 1/2009–12/2011 | NR | Surveillance swabs (26), urine (13), respiratory tract (12), skin and soft tissue (10), blood (5), other (10), and NR (7) k | CRE; E. aerogenes (121), E. coli (104), E. cloacae (100), Serratia marcescens (19), Providencia stuartii (11), Pantoea agglomerans (10), Citrobacter freundii (8), K. oxytoca (9), and Morganella morganii (5) | 83/387 (21) | blaKPC-2 |

| Tolentino, 2019 [115] | South America | Brazil | 2011–2014 | Inpatient, 48/48 (100) | NR | K. pneumoniae | 48/48 (100) | blaKPC-2 |

| Quesille-Villalobos, 2025 [119] | South America | Chile | 1/2019–12/2022 | Inpatient | Biopsies, blood, bone tissue, sterile fluids, and other | CPE; K. pneumoniae, E. cloacae complex, E. coli, Citrobacter spp., and K. oxytoca | 2019: 8/12 (67) 2020: 35/60 (58) 2021: 69/168 (41) 2022: 87/190 (46) 2019–2020: 199/430 (46) | blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3 |

| Ibáñez-Prada, 2024 [116] | South America | Colombia | 7/2017–7/2021 | Inpatient, 189/248 (76) ICU | NR | CRE; K. pneumoniae, Enterobacter hormaechei, Klebsiella variicola subsp. variicola, Providencia rettgeri, and P. aeruginosa | 171/228 (75) | blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3 |

| Ocampo, 2016 [117] | South America | Colombia | 6/2012–6/2014 | Inpatient, 28/193 (15) children, 55/193 (29) ICU | NR | K. pneumoniae | 166/193 (86) | blaKPC |

| Soria-Segarra, 2024 [120] | South America | Ecuador | 1/2022–5/2022 | Clinical isolates | NR | CPE; K. pneumoniae, K. aerogenes, E. cloacae, E. coli, A. baumannii, and P. aeruginosa | 52/60 (87) | blaKPC |

| Lascols, 2012 [135] | Various; Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America, the Middle East, North America, South Pacific | NR | 2008–2009 | Clinical isolates | Intra-abdominal infections | E. coli, K. oxytoca, K. pneumoniae, and Proteus mirabilis | 28/1093 (3) | blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3, blaKPC-11 |

| Wise, 2023 [136] | Various; Africa/Middle East, Asia, Eurasia, Latin America | 27 countries l | 2019–2021 | Inpatient, 6632/24,937 (27) ICU | Urinary tract (6408), bloodstream (5921), lower respiratory tract (4907), skin/soft tissue (4400), intra-abdominal (3263), and other (38) | Enterobacterales | 705/7446 m (9) | blaKPC |

| Hawser, 2009 [131] | Various; America, Asia, Europe | Israel, Puerto Rico, Colombia, and Greece | 2005–2008 | Clinical isolates | NR | NR | 26/86 (30) | blaKPC |

| Doyle, 2012 [129] | Various; Asia, Europe, Latin America, Middle East, North America, the South Pacific | NR | 2008–2009 | Clinical isolates | NR | CPE; Klebsiella spp., E. coli, Citrobacter freundii, and Enterobacter spp. | 49/142 (35) | blaKPC |

| Karlowsky, 2022 [132] | Various; Asia, Europe, Latin America, North America | 52 countries | 2018–2020 | NR | Urinary tract (1210), respiratory tract (998), blood (823), intra-abdominal (409), and skin/soft tissue (449) | Enterobacterales | 230/1265 (18) | blaKPC |

| Gales, 2023 [130] | Various; Asia/Pacific, Europe, Latin America, Middle East/Africa, North America | NR n | 2017–2019 | Inpatient | Blood, intra-abdominal, other (nervous system, reproductive system, head, ears, eyes, nose and throat), respiratory tract, skin/musculoskeletal, urinary tract, and instruments | E. coli (20,047), P. aeruginosa (20,643), K. pneumoniae (17,229), and E. cloacae (6866) | 830/64,785 (1) | blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3 |

| Castanheira, 2019 [128] | Various; Asia/Pacific, Europe, Latin America, North America | 42 countries | 2007–2016 | NR | NR | CRE; K. pneumoniae (997), E. cloacae species complex (69), E. coli (52), Serratia marcescens (44), K. oxytoca (30), K. aerogenes (27), Citrobacter freundii species complex (9), Proteus mirabilis (6), Enterobacter spp. (4), Raoultella ornithinolytica (3), Pluralibacter gergoviae (2), Providencia stuartii (2), Raoultella planticola (2), Serratia spp. (2), Hafnia alvei (1), Morganella morganii (1), Pantoea agglomerans (1), and Raoultella spp. (1) | 2007–2009: 186/1298 (50) 2014–2016: 501/1298 (54) | blaKPC-2, blaKPC-3, blaKPC-4, blaKPC-6, blaKPC-12, blaKPC-17, blaKPC-20, blaKPC-like o |