Microbiome and Microbiota Within Wineries: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

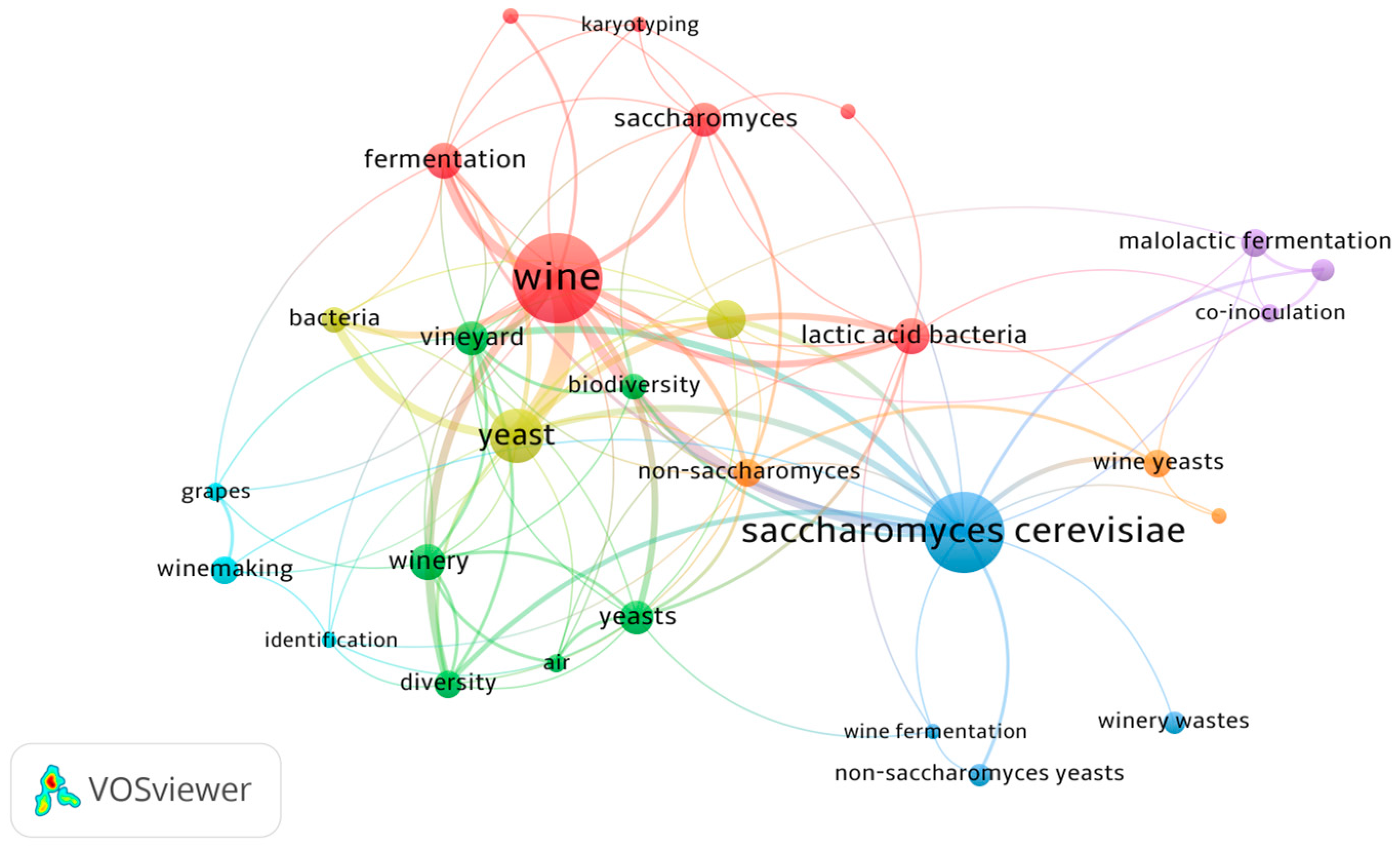

2. Methodology

3. Microbiology of Grape Berries, Must and Winery Surfaces

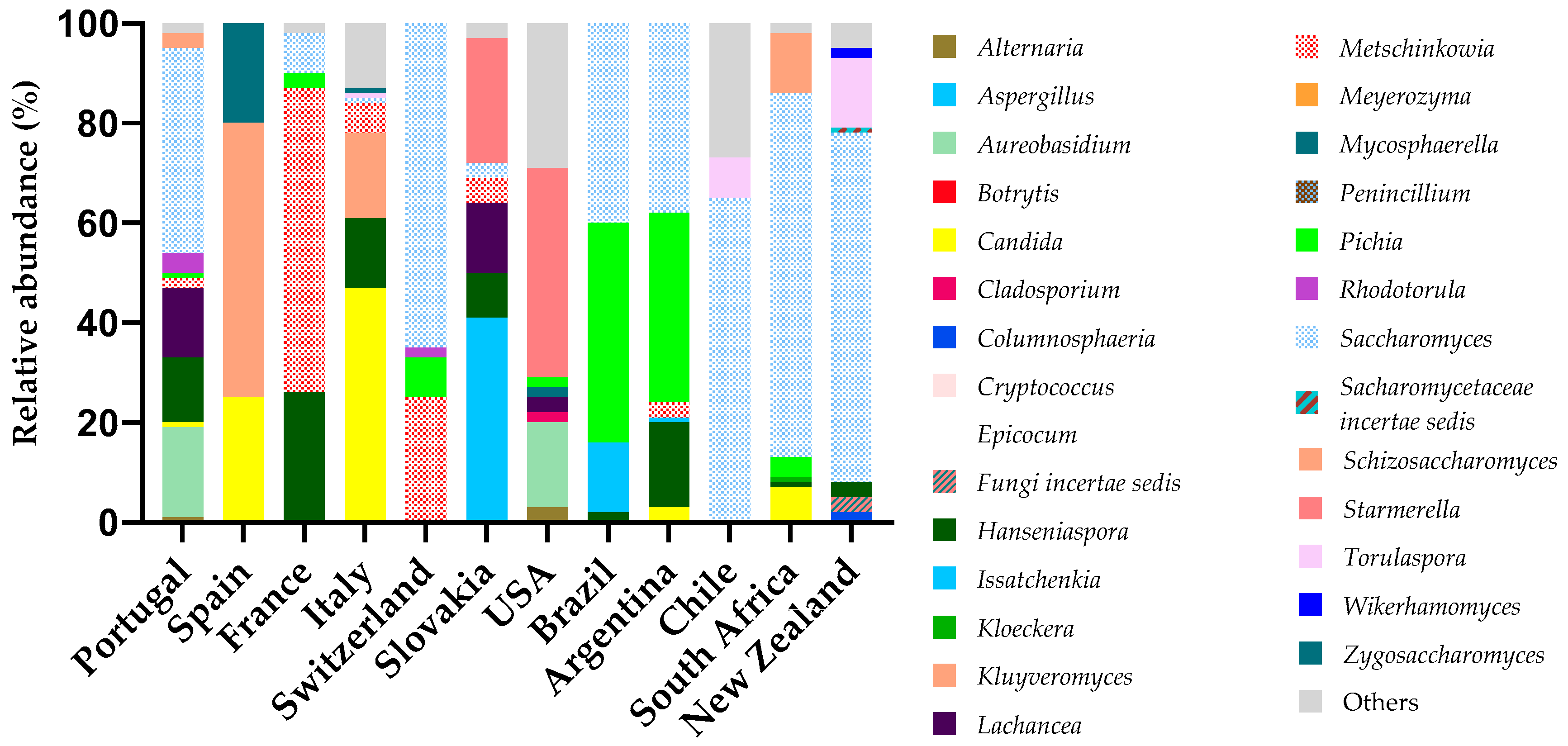

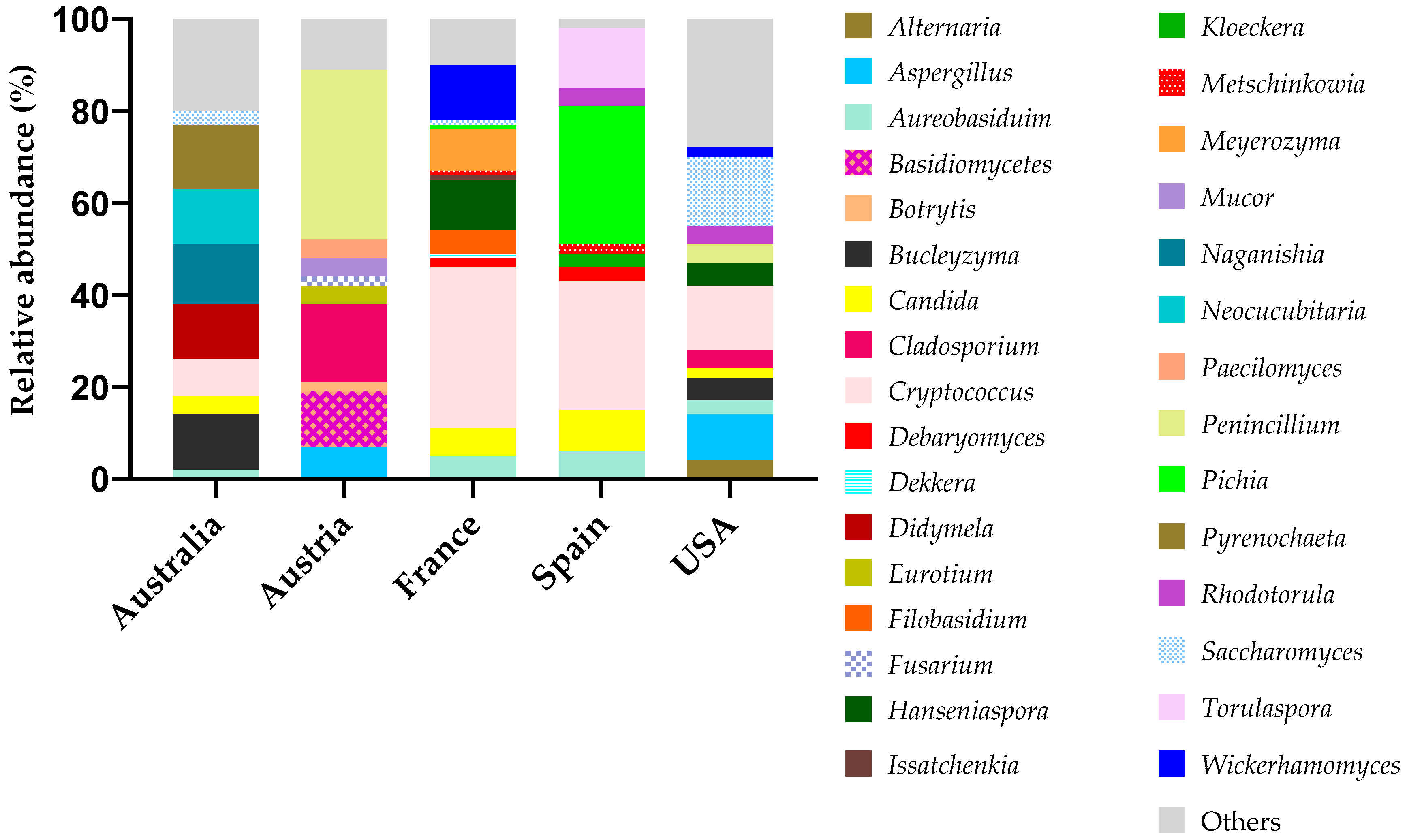

3.1. Microbiology of Grape Berries

| Sample | Methods | Sampling | Fungi Taxa | Bacteria Taxa | Location, Country | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grapes from Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon and Cabernet Franc | Cultural methods and PCR-RFLP-ITS (fungi), PCR-DGGE (bacteria) | Grape from 3 vineyards at different stages (berry set for harvest) | A. pullulans, Yarrowia lipolytica, C. boidinii, Candida fructus, Candida intermedia, Candida membranifaciens, Candida stellata, Lipomyces spencermartinsiae, Met. pulcherrima, Debaryomyces hansenii, Issatchenkia orientalis, Issatchenkia terricola, Kluyveromyces lactis, P. anomala, Pichia fermentans, Saccharomyces boulardii, S. cerevisiae, H. guillermondii, H. opuntiae, H. uvarum, Bulleromyces albus, Cr. albidus, Cr. flavescens, Papiliotrema laurentii, Rhodosporidium babjevae, Rh. glutinis, Rh. graminis, Rh. mucilaginosa, Sporidiobolus pararoseus, S. salmonicolor, Sporobolomyces roseus | Enterobacter, Serratia, Gluconobacter oxydans, O. oeni, Pediococcus parvulus, Burkholderia vietnamiensis | Not mentioned, France | [20] |

| Merlot grapes from two vineyards | Cultural methods and T-RFLP | Beginning of grape ripening, healthy and undamaged grapes | Pseudomonas, Massilia, Micrococcus Curtobacterium Brevibacterium Enterobacter, Burkholderia | Lussac St. Emilion, France | [32] | |

| Merlot grapes from five vineyards | Illumina (NGS) | During harvesting | Sphingomonas, Pseudomonas, Methylobacterium | Long Island, USA | [22] | |

| Sauvignon blanc grapes | Pyrosequencing (NGS) | During harvesting | Cladosporium, Davidiella Columnosphaeria, Botryotinia Torulaspora, Saccharomyces Hanseniaspora, Pleosporales Trichocomaceae | Six wine regions (36 vineyards), New Zealand | [23] | |

| Grapes from Peloponnese peninsula, Santorini, Crete (33 vineyards) | Culture followed by PCR-RFLP | Grapes from 2–9 sampling plots per vineyard | A. pullulans, C. diversa, C. glabrata, C. membranifaciens, C. tropicalis, Cr. diffluens, H. uvarum, H. guilliermondii, H. opuntiae, Hyphopichia pseudoburtonii, L. thermotolerans, Meyerozyma caribbica, Met. pulcherrima, Papiliotrema laurentii, Pichia anomala, S. cerevisiae, Starmerella bacillaris, Torulaspora delbrueckii | Peloponnese peninsula, Santorini and Crete islands, Greece | [29] | |

| Grape varieties Faith and Gratitude | Illumina (NGS) | Grape berries 7 days before harvest | Meyerozyma, Candida, Cladosporium, Saccharomycetales, Filobasidium, Papiliotrema, Zygoascus, Hanseniaspora, Hannaella, Didymella, Dissoconium Less abundant: A. pullulans, Metschnikowia, Pichia, Rhodotorula, Cryptococcus | Not mentioned, USA | [43] | |

| Grapes from Cabernet Sauvignon, Marselan, Merlot, Chardonnay, Petit Manseng, Petit Verdott, Cabernet Franc, Beimei, Beihong, Syrah, Vidal | Cultural methods; molecular identification | Grape berries near ripening/harvest (11 varieties, 9 wine regions, 3 vineyards, 2 consecutive years) | H. uvarum, H. opuntiae, H. occidentalis, H. vineae, R. paludigena, R. nothofagi, C. glabrata, C. apicola, C. xestobii, C. silosis, M. caribbica, M. guilliermondii, Met. pulcherrima, Met. chrysoperlae, K. exigua, K. hellenicae, Cr. flavescens, Issatchenkia terricola, S. bacillaris, T. delbrueckii, K. marxianus, Z. bailii, Clavispora lusitaniae, A. pullulans, Wickerhamomyces anomalus, Cyberlindnera fabianii | Several regions, China | [31] | |

| Grapes from two vineyards (organic versus conventional management) | Culture followed by molecular identification of the isolates | Grape berries 6/8 days before harvest | A. pullulans, Cladosporium ramotenellium, C. cladosporoides, Naganishia globosa, F. magnum, H. uvarum, Zygosaccharomyces rouxii, S. bacillaris, Paraconiothyrium sp. | Valpolicella DOC wine region, Italy | [28] | |

| Grapes of Maraština cultivar (11 vineyards) | Illumina (NGS) | Mature, healthy and undamaged grapes | Alternaria, Aureobasidium Cladosporium, Filobasidium Hanseniaspora, Metschnikowia Quambalaria (<1%): Botrytis, Buckleyzyma, Cryptococcus, Cystobasidium, Didymella, Eremothecium, Hyphopichia, Penicillium, Pichia, Plenodomus, Sporobolomyces | Dalmatian coast, Croatia | [24] | |

| Grapes of red wine cultivars from 7 vineyards | Illumina (NGS) | During harvesting | Alternaria, Aureobasodium, Cladosporium, Curvularia, Filobasidium, Pseudopithomyces Vishniacozyma | Pseudomonas Sphingomonadaceae Massilia Methylobacterium | Northeast Macedonia Region, Greece | [30] |

3.2. Microbiology of Must

3.3. Microbiology of Winery Surfaces

3.4. Air Microbiology

| Sampling Method | Media | Incubation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| One-stage SAS Compact sampler, 1.2 m above ground (60 L/sample) | MEA, MESA | 8–15 days (22 or 37 °C) | [80] |

| SKC BioSampler system 1, 250 L/sample | BSE | 40–48 h (30 °C) | [81] |

| MAS-100 Eco air sampler (≤100 L per sample) | TSA, MCA, META | TSA: 3 days (30 °C) MCA: 3 days (33 °C) META: 4 days (27 °C) | [79] |

| MAS-100 Eco air sampler, 1.5 m above ground (20, 50, 100 L air) | MEA, CASO-agar, DG18 | 6 days (RT or 28 °C) | [82] |

| Air IDEAL 3P air sampler, 1 m above ground (20–100 L) | CGA, CZA, MRS-agar | 48 h–7 days (25 °C), 10 days (30 °C, anaerobiosis) | [75] |

| Air IDEAL 3P air sampler, 1 m above ground (1500 L/sample) | MRS-agar with 50 mg/L of pimaricin | 10 days (30 °C) | [61] |

| Six-stage Andersen-Cascade impactor, cut-off size (d50), 1.5 m above ground (56.6 L/sample) | MEA, DG18 | 7 days (25 °C) | [67] |

| Air IDEAL 3P air sampler, 1 m above ground (100 L/sample) | CZA | 7 days (20 °C) | [83] |

| Air IDEAL 3P air sampler (500 or 1500 L/sample) | CGA, MR-agar (enriched TSB) | 3 days (25 °C) | [84] |

| Air IDEAL 3P air sampler, 1 m above ground (500 or 1500 L/sample) | CGA, MR-agar (enriched TSB) | 3 days (25 °C) | [85] |

| AirPort MD8 air sampler, 1 m above ground (LAB—1000 L; yeast—250 L per sample) | MRS, CGA | LAB: 5 days (30 °C) Yeast: 2 days (25 °C) | [64] |

| Air Ideal air sampler (100–250 L) | TSA, TSA-HN 2 | 3 days (37 °C) with or without CO2 | [86] |

| One-stage volumetric sieve sampler (SAS IAQ) | PDA, MEA, RBA (with chloramphenicol) | 3–8/15 days (25 °C) | [73] |

| Koch sedimentation method, 0.6 m above ground or ceiling level, 4 h exposure | SDAC (0.5 g/L) | 10 days (25 °C) | [87] |

4. Microbial Risks in Wineries

4.1. Risks to the Wine

| Taxa (Genus/Species) or Group) | Metabolites | Instability/Flavors/Risks/Faults |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria | ||

| Bacillus (B. subtilis, B. circulans, B. coagulans) | Long-chain polysaccharides | Sediment/haze formation, ropiness, viscous |

| LAB | Acetic acid | Vinegar |

| Lactobacillus | Acrolein * | Bitterness |

| Lactobacillus, Oenococcus | diacetyl (2,3-butanedione) | Buttery, nutty, caramel |

| Lactobacillus, Pediococcus | 2-Ethoxy-3,5-hexadiene | Crushed geranium leaves |

| Lactobacillus, O. oeni | 2-Acetyl-tetrahydropyridine, 2-Ethyl-tetrahydropyridine | Caged mouse/mousy |

| Oenococcus | Mannitol | Viscous, sweet |

| Leuconostoc, Pediococcus | β-D-glucan | Viscous and thick |

| AAB, LAB | Acetic acid, Ethyl acetate | Vinegar, solvent-like aroma, nail polish removal |

| AAB (Acetobacter, Gluconobacter) | Acetaldehyde ** | Bruised apple, sherry-like, nutty |

| O. oeni | Ethyl carbamate ** | Saline, bitter taste |

| Streptomyces | Guaiacol, 4-methylguaiacol | Smoked, phenolic and medicinal odors |

| Yeasts | ||

| Candida | Acetic acid, ethyl acetate | Vinegar, nail polish removal, |

| C. boidinii P. guilliermondii | 4-vinylphenol 4-vinylphenol, 4-ethylphenol | Barnyard, medicinal, band-aids, mousy |

| Brettanomyces/Dekkera | 4-ethylphenol, 4-ethyl guaiacol, 2-acetyl-tetrahydropyridine, 2-ethyl-tetrahydropyridine | Barnyard-like, horsy, wet wool, sweaty saddle, medicinal, mousy |

| Hansenula | Acetic acid, ethyl acetate | Vinegar, nail polish removal, film formation |

| Kloeckera/Hanseniaspora | Acetic acid, ethyl acetate | Vinegar, nail polish removal, film formation, yeasty and estery aromas |

| Pichia (P. membranifaciens, P. anomala) | Ethyl acetate | Film formation, nail polish removal |

| Saccharomyces | NA | Cloudiness, sediment, yeasty aroma/flavor |

| S. cerevisiae | Hydrogen sulphide | Rotten-egg off-flavor |

| Saccharomycodes | Acetoin, ethyl acetate, acetic acid | Film/sediment formation, gas production, vinegar, nail polish removal |

| Schizosaccharomyces | NA | Sediment |

| Zygosaccharomyces | NA | Haze or deposit after bottling |

| Molds | ||

| B. cinerea | 1-octen-3-ol, 1-octen-3-one | Metallic, fresh mushrooms |

| B. cinerea, P. expansum | Geosmin (trans-1,10-dimethyl-trans-9-decalol) | Dump hearth, humus, dump cellar |

| Aspergillus (A. niger), Paecilomyces, P. chrysogenum, P. glabrum, Mucor racemosus, Trichoderma viride | 2,4,6-trichloroanisole (TCA) 2,3,4,6-tetrachloroanisole (TeCA) 2,4,6-tribromoanisole (TBA) | Cork taint, wet dog Moldy cellar odor Moldy and mushrooms |

4.2. Risks to the Wine Consumers, Workers and Visitors

5. Challenges in Wineries

5.1. Microbiology of Wineries and Climate Change

| Growth at | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeast Species | 19 °C | 25 °C | 34 °C | 37 °C | 40 °C |

| Candida apicola | + | + | v | − | − |

| Candida bombi | + | + | + | + | − |

| Candida parapsilosis | + | + | + | + | v |

| Candida stellatta | + | + | v | − | − |

| Candida sake | + | + | − | − | − |

| Candida vini | + | + | − | − | − |

| Debaryomyces carsonii * | + | + | nd | v | nd |

| Debaryomyces hansenii ** | + | + | + | + | nd |

| Dekkera bruxelensis | + | + | + | + | v |

| Hanseniaspora guilliermondii | + | + | + | + | − |

| Hanseniaspora uvarum | + | + | nd | − | − |

| Issatchenkia occidentalis | nd | + | + | + | − |

| Kloeckera lindneri | + | + | − | − | − |

| Kluveryomyces thermotolerans | + | + | + | v | nd |

| Metschnikowia pulcherrima | + | + | nd | v | nd |

| Pichia anomala | + | + | nd | v | nd |

| Pichia membranifaciens | + | + | nd | v | nd |

| Saccharomyces bayanus | + | + | v | − | − |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | + | + | v | v | v |

| Schizosaccharomyces pombe | + | + | nd | − | nd |

| Torulaspora delbrueckii | + | + | nd | v | nd |

| Zygosaccharomyces bailii | + | + | nd | v | nd |

5.2. Wineries’ Design

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reynolds, A.G. The Grapevine, Viticulture, and Winemaking: A Brief Introduction. In Grapevine Viruses: Molecular Biology, Diagnostics and Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGovern, P.; Jalabadze, M.; Batiuk, S.; Callahan, M.P.; Smith, K.E.; Hall, G.R.; Kvavadze, E.; Maghradze, D.; Rusishvili, N.; Bouby, L.; et al. Early neolithic wine of georgia in the south caucasus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E10309–E10318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIV. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/what-we-do/data-discovery-report?oiv (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- OIV. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/who-we-are/member-states-and-observers (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Firstleaf. Available online: https://www.firstleaf.com/wine-school/article/wine-statistics (accessed on 15 February 2024).

- Fugelsang, K.C.; Edwards, C.G. Managing Microbial Growth. In Wine Microbiology—Practical Applications and Procedures; Springer: New York, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Van Leeuwen, C.; Destrac-Irvine, A.; Gowdy, M.; Farris, L.; Pieri, P.; Marolleau, L.; Gambetta, G.A. An operational model for capturing grape ripening dynamics to support harvest decisions. OENO One 2023, 57, 505–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liao, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Bi, J.; Liu, Y.; Song, Y.; Qin, Y. Revealing the flavor differences of Sauvignon Blanc wines fermented in different oak barrels and stainless-steel tanks through GC-MS, GC-IMS, Electronic, and Artificial Sensory Analyses. Food Chem. X 2025, 25, 102188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbi, A.; Acedo, A.; Imam, N.; Santini, R.G.; Ortiz-Álvarez, R.; Ellegaard-Jensen, L.; Belda, I.; Hansen, L.H. A Global microbiome survey of vineyard soils highlights the microbial dimension of viticultural terroirs. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, G.C.; Leiva, J.; Nand, S.; Lee, D.M.; Hajkowski, M.; Dick, K.; Withers, B.; Soto, L.; Mingoa, B.-R.; Acholonu, M.; et al. Soil microbial communities and wine terroir: Research gaps and data needs. Foods 2024, 13, 2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Collins, T.S.; Masarweh, C.; Allen, G.; Heymann, H.; Ebeler, S.E.; Mills, D.A. Associations among wine grape microbiome, metabolome, and fermentation behavior suggest microbial contribution to regional wine characteristics. mBio 2016, 7, e00631-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belda, I.; Zarraonaindia, I.; Perisin, M.; Palacios, A.; Acedo, A. From vineyard soil to wine fermentation: Microbiome approximations to explain the “terroir” concept. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGovern, P.E.; Glusker, D.L.; Exner, L.J.; Voigt, M.M. Neolithic resinated wine. Nature 1996, 381, 480–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Zhang, P.; Chen, D.; Howell, K. From the vineyard to the winery: How microbial ecology drives regional distinctiveness of wine. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Styger, G.; Prior, B.; Bauer, F.F. Wine flavor and aroma. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 38, 1145–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubeck, A.M.; Preiss, L.; Jung, A.; Dörner, E.; Podlesny, D.; Kulis, M.; Maddox, C.; Arze, C.; Zörb, C.; Merkt, N.; et al. Bacterial microbiota diversity and composition in red and white wines correlate with plant-derived DNA contributions and Botrytis infection. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 13828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griggs, R.G.; Steenwerth, K.L.; Mills, D.A.; Cantu, D.; Bokulich, N.A. Sources and assembly of microbial communities in vineyards as a functional component of winegrowing. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 673810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiter, T.; Montpetit, R.; Byer, S.; Frias, I.; Leon, E.; Viano, R.; Mcloughlin, M.; Halligan, T.; Hernandez, D.; Figueroa-Balderas, R.; et al. Transcriptomics provides a genetic signature of vineyard site and offers insight into vintage-independent inoculated fermentation outcomes. mSystems 2021, 6, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barata, A.; Malfeito-Ferreira, M.; Loureiro, V. The microbial ecology of wine grape berries. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 153, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renouf, V.; Claisse, O.; Lonvaud-Funel, A. Understanding the microbial ecosystem on the grape berry surface through numeration and identification of yeast and bacteria. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2005, 11, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, Q.; Wang, P.; Lin, J.; Huang, L.; Xu, Y. Synergistic effect in core microbiota associated with sulfur metabolism in spontaneous Chinese liquor fermentation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e01475-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarraonaindia, I.; Owens, S.M.; Weisenhorn, P.; West, K.; Hampton-Marcell, J.; Lax, S.; Bokulich, N.A.; Mills, D.A.; Martin, G.; Taghavi, S.; et al. The soil microbiome influences grapevine-associated microbiota. mBio 2015, 6, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison-Whittle, P.; Goddard, M.R. From vineyard to winery: A source map of microbial diversity driving wine fermentation. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 20, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milanović, V.; Cardinali, F.; Ferrocino, I.; Boban, A.; Franciosa, I.; Gajdoš Kljusurić, J.; Mucalo, A.; Osimani, A.; Aquilanti, L.; Garofalo, C.; et al. Croatian white grape variety Maraština: First taste of its indigenous mycobiota. Food Res. Int. 2022, 162, 111917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavijo, A.; Calderón, I.L.; Paneque, P. Diversity of Saccharomyces and non-Saccharomyces Yeasts in three red grape varieties cultured in the Serranía de Ronda (Spain) vine-growing region. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 143, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleet, G.H. Yeast-growth during fermentation. J. Wine Res. 1990, 1, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raspor, P.; Milek, D.M.; Polanc, J.; Smole Možina, S.; Čadež, N. Yeasts isolated from three varieties of grapes cultivated in different locations of the Dolenjska vine-growing Region, Slovenia. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 109, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, T.; Gaiotti, F.; Tomasi, D. Characterization of indigenous microbial communities in vineyards employing different agronomic practices: The importance of trunk bark as a source of microbial biodiversity. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalvantzi, I.; Banilas, G.; Tassou, C.; Nisiotou, A. Biogeographical regionalization of wine yeast communities in Greece and environmental drivers of species distribution at a local scale. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 705001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekris, F.; Papadopoulou, E.; Vasileiadis, S.; Karapetsas, N.; Theocharis, S.; Alexandridis, T.K.; Koundouras, S.; Karpouzas, D.G. Vintage and terroir are the strongest determinants of grapevine carposphere microbiome in the viticultural zone of Drama, Greece. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2025, 101, fiaf008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Qing, X.; Yang, S.; Li, R.; Zhan, J.; You, Y.; Huang, W. Study on the Diversity of non-Saccharomyces yeasts in Chinese wine regions and their potential in improving wine aroma by β-glucosidase activity analyses. Food Chem. 2021, 360, 129886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, G.; Lauga, B.; Miot-Sertier, C.; Mercier, A.; Lonvaud, A.; Soulas, M.-L.; Soulas, G.; Masneuf-Pomarède, I. Characterization of epiphytic bacterial communities from grapes, leaves, bark and soil of grapevine plants grown, and their relations. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grangeteau, C.; Roullier-Gall, C.; Rousseaux, S.; Gougeon, R.D.; Schmitt-Kopplin, P.; Alexandre, H.; Guilloux-Benatier, M. Wine microbiology is driven by vineyard and winery anthropogenic factors. Microb. Biotechnol. 2017, 10, 354–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, S.; Klaere, S.; Fedrizzi, B.; Goddard, M.R. Regional Microbial Signatures Positively correlate with differential wine phenotypes: Evidence for a microbial aspect to terroir. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertin, W.; Setati, M.E.; Miot-Sertier, C.; Mostert, T.T.; Colonna-Ceccaldi, B.; Coulon, J.; Girard, P.; Moine, V.; Pillet, M.; Salin, F.; et al. Hanseniaspora uvarum from winemaking environments show spatial and temporal genetic clustering. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 6, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banilas, G.; Sgouros, G.; Nisiotou, A. Development of microsatellite markers for Lachancea thermotolerans typing and population structure of wine-associated isolates. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 193, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lleixà, J.; Kioroglou, D.; Mas, A.; Portillo, M. del C. Microbiome dynamics during spontaneous fermentations of sound grapes in comparison with sour rot and Botrytis infected grapes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 281, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzini, M.; Simonato, B.; Favati, F.; Bernardi, P.; Sbarbati, A.; Zapparoli, G. Filamentous fungi associated with natural infection of noble rot on withered grapes. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2018, 272, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Li, T.; Xu, X.; Shi, X.; Wang, B. Succession of fungal communities at different developmental stages of Cabernet Sauvignon grapes from an organic vineyard in Xinjiang. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 718261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dachery, B.; Hernandes, K.C.; Veras, F.F.; Schmidt, L.; Augusti, P.R.; Manfroi, V.; Zini, C.A.; Welke, J.E. Effect of Aspergillus carbonarius on ochratoxin a levels, volatile profile and antioxidant activity of the grapes and respective wines. Food Res. Int. 2019, 126, 108687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, S.L.; Hocking, A.D.; Pitt, J.I.; Kazi, B.A.; Emmett, R.W.; Scott, E.S. Australian research on ochratoxigenic fungi and ochratoxin a. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 111, S10–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testempasis, S.I.; Papazlatani, C.V.; Theocharis, S.; Karas, P.A.; Koundouras, S.; Karpouzas, D.G.; Karaoglanidis, G.S. Vineyard practices reduce the incidence of Aspergillus spp. and alter the composition of carposphere microbiome in grapes (Vitis vinifera L.). Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1257644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cureau, N.; Threlfall, R.; Savin, M.; Marasini, D.; Lavefve, L.; Carbonero, F. Year, location, and variety impact on grape-, soil-, and leaf-associated fungal microbiota of Arkansas-grown table grapes. Microb. Ecol. 2021, 82, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capozzi, V.; Garofalo, C.; Chiriatti, M.A.; Grieco, F.; Spano, G. Microbial terroir and food innovation: The case of yeast biodiversity in wine. Microbiol. Res. 2015, 181, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilo, S.; Chandra, M.; Branco, P.; Malfeito-Ferreira, M. Wine microbial consortium: Seasonal sources and vectors linking vineyard and winery environments. Fermentation 2022, 8, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, C.; Pinho, D.; Cardoso, R.; Custódio, V.; Fernandes, J.; Sousa, S.; Pinheiro, M.; Egas, C.; Gomes, A.C. Wine fermentation microbiome: A landscape from different Portuguese wine appellations. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocón, E.; Gutiérrez, A.R.; Garijo, P.; López, R.; Santamaría, P. Presence of non-Saccharomyces yeasts in cellar equipment and grape juice during harvest time. Food Microbiol. 2010, 27, 1023–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciani, M.; Comitini, F. Yeast interactions in multi-starter wine fermentation. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2015, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, C.; Molina, A.M.; Nähring, J.; Fischer, R. Characterization and dynamic behavior of wild yeast during spontaneous wine fermentation in steel tanks and amphorae. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 540465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabegović, I.; Malićanin, M.; Danilović, B.; Stanojević, J.; Stamenković Stojanović, S.; Nikolić, N.; Lazić, M. Potential of Non-Saccharomyces yeast for improving the aroma and sensory profile of Prokupac red wine. OENO One 2021, 55, 181–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grangeteau, C.; Gerhards, D.; Rousseaux, S.; von Wallbrunn, C.; Alexandre, H.; Guilloux-Benatier, M. Diversity of yeast strains of the genus Hanseniaspora in the winery environment: What is their involvement in grape must fermentation? Food Microbiol. 2015, 50, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romancino, D.P.; Di Maio, S.; Muriella, R.; Oliva, D. Analysis of non-Saccharomyces yeast populations isolated from grape musts from Sicily (Italy). J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 105, 2248–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhmer, M.; Smoľak, D.; Ženišová, K.; Čaplová, Z.; Pangallo, D.; Puškárová, A.; Bučková, M.; Cabicarová, T.; Budiš, J.; Šoltýs, K.; et al. Comparison of microbial diversity during two different wine fermentation processes. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2020, 367, fnaa150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.L.; Hopfer, H.; Cockburn, D.W.; Wee, J. Characterization of microbial dynamics and volatile metabolome changes during fermentation of Chambourcin hybrid grapes from two Pennsylvania regions. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 614278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezerra-Bussoli, C.; Baffi, M.A.; Gomes, E.; Da-Silva, R. Yeast diversity isolated from grape musts during spontaneous fermentation from a Brazilian winery. Curr. Microbiol. 2013, 67, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerard, L.M.; Corrado, M.B.; Davies, C.V.; Soldá, C.A.; Dalzotto, M.G.; Esteche, S. Isolation and identification of native yeasts from the spontaneous fermentation of grape musts. Arch. Microbiol. 2023, 205, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandakovic, D.; Pulgar, R.; Maldonado, J.; Mardones, W.; González, M.; Cubillos, F.A.; Cambiazo, V. Fungal diversity analysis of grape musts from central valley-Chile and characterization of potential new starter cultures. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zyl, J.A.; Du Plessis, L.D.W. The microbiology of South African winemaking. Part I. The yeasts occurring in vineyards, musts and wines. S. Afr. J. Agric. Sci. 1961, 4, 393–403. [Google Scholar]

- Torija, M.J.; Rozès, N.; Poblet, M.; Guillamón, J.M.; Mas, A. Yeast population dynamics in spontaneous fermentations: Comparison between two different wine-producing areas over a period of three years. Anton. Leeuw. Int. J. G 2001, 79, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christaki, T.; Tzia, C. Quality and safety assurance in winemaking. Food Control 2002, 13, 503–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garijo, P.; López, R.; Santamaría, P.; Ocón, E.; Olarte, C.; Sanz, S.; Gutiérrez, A.R. Presence of lactic bacteria in the air of a winery during the vinification period. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 136, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Arenzana, L.; Santamaría, P.; López, R.; Tenorio, C.; López-Alfaro, I. Ecology of indigenous lactic acid bacteria along different winemaking processes of Tempranillo red wine from La Rioja (Spain). Sci. World J. 2012, 2012, 796327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, C.; Krupovic, M.; Jaomanjaka, F.; Claisse, O.; Petrel, M.; Le Marrec, C. Bacteriophage GC1, a Novel Tectivirus Infecting Gluconobacter cerinus, an acetic acid bacterium associated with winemaking. Viruses 2018, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Martín, F.; Seseña, S.; Fernández-González, M.; Arévalo, M.; Palop, M.L. Microbial communities in air and wine of a winery at two consecutive vintages. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 190, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokulich, N.A.; Ohta, M.; Richardson, P.M.; Mills, D.A. Monitoring seasonal changes in winery-resident microbiota. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, C.; Cuijvers, K.; Borneman, A. Temporal comparison of microbial community structure in an Australian winery. Fermentation 2021, 7, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, D.; Galler, H.; Habib, J.; Melkes, A.; Schlacher, R.; Buzina, W.; Friedl, H.; Marth, E.; Reinthaler, F.F. Concentrations of viable airborne fungal spores and trichloroanisole in wine cellars. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 144, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdo, H.; Catacchio, C.R.; Ventura, M.; D’Addabbo, P.; Alexandre, H.; Guilloux-Bénatier, M.; Rousseaux, S. The establishment of a fungal consortium in a new winery. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 7962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabate, J.; Cano, J.; Esteve-Zarzoso, B.; Guillamón, J.M. Isolation and identification of yeasts associated with vineyard and winery by RFLP analysis of ribosomal genes and mitochondrial DNA. Microbiol. Res. 2002, 157, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosini, G. Assessment of dominance of added yeast in wine fermentation and origin of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in wine-making. J. Gen. Appl. Microbiol. 1984, 30, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.N.; Magalhães, R.; Campos, F.M.; Couto, J.A. Survival and metabolism of hydroxycinnamic acids by Dekkera bruxellensis in monovarietal wines. Food Microbiol. 2021, 93, 103617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccarone, C.; Petruzzi, L.; Bevilacqua, A.; Sinigaglia, M. Qualitative survey of fungi isolated from wine-aging environment. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2012, 47, 1138–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magyar, D.; Kállai, Z.; Sipiczki, M.; Dobolyi, C.; Sebők, F.; Beregszászi, T.; Bihari, Z.; Kredics, L.; Oros, G. Survey of viable airborne fungi in wine cellars of Tokaj, Hungary. Aerobiologia 2018, 34, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippis, F.; Valentino, V.; Alvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Cotter, P.D.; Ercolini, D. Environmental microbiome mapping as a strategy to improve quality and safety in the food Industry. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2021, 38, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garijo, P.; Santamaría, P.; López, R.; Sanz, S.; Olarte, C.; Gutiérrez, A.R. The occurrence of fungi, yeasts and bacteria in the air of a Spanish winery during vintage. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 125, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loveniers, P.-J.; Devlieghere, F.; Sampers, I. Towards. Tailored guidelines for microbial air quality in the food industry. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2024, 421, 110779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łukaszuk, C.; Krajewska-Kułak, E.; Guzowski, A.; Kułak, W.; Kraszyńska, B. Comparison of the results of studies of air pollution fungi using the SAS Super 100, MAS 100, and Air IDEAL. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabral, J.P.S. Can we use indoor fungi as bioindicators of indoor air quality? Historical perspectives and open questions. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 4285–4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zollinger, M.; Krebs, W.; Brandl, H. Bioaerosol formation during grape stemming and crushing. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 363, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simeray, J.; Mandin, D.; Mercier, M.; Chaumont, J.-P. Survey of viable airborne fungal propagules in French wine cellars. Aerobiologia 2001, 17, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, L.; Stender, H.; Edwards, C.G. Rapid detection and identification of Brettanomyces from winery air samples based on peptide nucleic acid analysis. Am. J. Enol. Vitic 2002, 53, 322–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemenz, A.; Sterflinger, K.; Kneifel, W.; Mandl, K. Airborne fungal microflora of selected types of wine-cellars in Austria. Mitt. Klosterneubg. 2008, 58, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ocón, E.; Gutiérrez, A.R.; Garijo, P.; Santamaría, P.; López, R.; Olarte, C.; Sanz, S. Factors of influence in the distribution of mold in the air in a wine cellar. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, M169–M174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocón, E.; Garijo, P.; Sanz, S.; Olarte, C.; López, R.; Santamaría, P.; Gutiérrez, A.R. Analysis of airborne yeast in one winery over a period of one year. Food Control 2013, 30, 585–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocón, E.; Garijo, P.; Sanz, S.; Olarte, C.; López, R.; Santamaría, P.; Gutiérrez, A.R. Screening of yeast mycoflora in winery air samples and their risk of wine contamination. Food Control 2013, 34, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folayan, A.; Mohandas, K.; Kumarasamy, V.; Lee, N.; Mak, J.W. Kytococcus sedentarius and Micrococcus luteus: Highly prevalent in indoor air and potentially deadly to the immunocompromised-should standards be set? Trop. Biomed. 2018, 35, 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Ilieș, D.C.; Onet, A.; Mukthar Sonko, S.; Ilieș, A.; Gaceu, O.; Baias, Ș.G.; Ilieș, M.H.; Berdenov, Z.I.; Herman, G.J.; Sambou, A.K.; et al. Air quality in cellars: A case study of wine cellar in Sălacea, Romania. Folia Geograph. 2020, 62, 158–173. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R.I.; Miletto, M.; Taylor, J.W.; Bruns, T.D. Dispersal in microbes: Fungi in indoor air are dominated by outdoor air and show dispersal limitation at short distances. ISME J. 2013, 7, 1262–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannigan, B. Air sampling for fungi in indoor environments. J. Aerosol Sci. 1997, 28, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, B.G.; Kirkland, K.H.; Flanders, W.D.; Morris, G.K. Profiles of airborne fungi in buildings and outdoor environments in the United States. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 1743–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picco, A.M.; Rodolfi, M. Assessments of indoor fungi in selected wineries of Oltrepo Pavese (Northern Italy) and Sottoceneri (Switzerland). Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2004, 55, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prussin, A.J.; Garcia, E.B.; Marr, L.C. Total concentrations of virus and bacteria in indoor and outdoor air. Environ. Sci. Technol Lett 2015, 2, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Phelan, P.E.; Duan, T.; Raupp, G.B.; Fernando, H.J.S.; Che, F. Experimental study of indoor and outdoor airborne bacterial concentrations in Tempe, Arizona, USA. Aerobiologia 2003, 19, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zíková, N.; Ziembik, Z.; Olszowski, T.; Bożym, M.; Nabrdalik, M.; Rybak, J. Elemental and microbiota content in indoor and outdoor air using recuperation unit filters. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 789, 147903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocón, E.; Garijo, P.; Santamaría, P.; López, R.; Olarte, C.; Gutiérrez, A.R.; Sanz, S. Comparison of culture media for the recovery of airborne yeast in wineries. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2013, 57, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Collaborative Action. Indoor air quality and its impact on man-biological particles in indoor environments. In Environment and Quality of Life. Report No. 12: Biological Particles in Indoor Environments; Commission of the European Communities: Luxembourg, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.; Lyng, J.; Dunne, G.; Bolton, D.J. An assessment of the microbial quality of the air within a pork processing plant. Food Control 2008, 19, 915–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle Garcia, M.; Sonnenstrahl Bregão, A.; Parussolo, G.; Olivier Bernardi, A.; Stefanello, A.; Venturini Copetti, M. Incidence of spoilage fungi in the air of bakeries with different hygienic status. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 290, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, J.; Tascón, A.; Ayuga, F. Systematic layout planning of wineries: The case of Rioja Region (Spain). J. Agric. Eng. 2018, 49, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Toxicology Program. 15th Report on Carcinogens; National Toxicology Program: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- The Australian Wine Research Institute. Avoiding Spoilage Caused by Lactic Acid Bacteria; The Australian Wine Research Institute: Netherby, SA, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- La Guerche, S.; Chamont, S.; Blancard, D.; Dubourdieu, D.; Darriet, P. Origin of (−)-Geosmin on Grapes: On the complementary action of two fungi, Botrytis cinerea and Penicillium expansum. Anton. Leeuw. Int. J. G 2005, 88, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loureiro, V. Spoilage yeasts in the wine industry. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2003, 86, 23–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartowsky, E.J. Bacterial spoilage of wine and approaches to minimize it. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2009, 48, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prak, S.; Gunata, Z.; Guiraud, J.-P.; Schorr-Galindo, S. Fungal strains isolated from cork stoppers and the formation of 2,4,6-trichloroanisole involved in the cork taint of wine. Food Microbiol. 2007, 24, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangorrín, M.P.; Lopes, C.A.; Jofré, V.; Querol, A.; Caballero, A.C. Spoilage yeasts from Patagonian cellars: Characterization and potential biocontrol based on killer interactions. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 24, 945–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of California. Available online: https://wineserver.ucdavis.edu/industry-info/enology/wine-microbiology/bacteria/bacillus-sp (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Pegg, A.E. Toxicity of polyamines and their metabolic products. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2013, 26, 1782–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thangam, E.B.; Jemima, E.A.; Singh, H.; Baig, M.S.; Khan, M.; Mathias, C.B.; Church, M.K.; Saluja, R. The role of histamine and histamine receptors in mast cell-mediated allergy and inflammation: The hunt for new therapeutic targets. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.Z.; Nawaz, W. The emerging roles of human trace amines and human trace amine-associated receptors (HTAARs) in central nervous system. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2016, 83, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosnaim, A.D.; Wolf, M.E. β-Phenylethylamine-class trace amines in neuropsychiatric disorders. In Trace Amines and Neurological Disorders; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, A.M.; Carvalho, F.; Bastos, M.d.L. Guedes de Pinho, P.; Carvalho, M. The hallucinogenic world of tryptamines: An updated review. Arch. Toxicol. 2015, 89, 1151–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szeliga, M.; Albrecht, J. Roles of nitric oxide and polyamines in brain tumor growth. Adv. Med. Sci. 2021, 66, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleixandre, J.L.; Aleixandre-Tudó, J.L.; Bolaños-Pizarro, M.; Aleixandre-Benavent, R. Viticulture and oenology scientific research: The old world versus the new world wine-producing countries. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozzi, V.; Ladero, V.; Beneduce, L.; Fernández, M.; Alvarez, M.A.; Benoit, B.; Laurent, B.; Grieco, F.; Spano, G. Isolation and characterization of tyramine-producing Enterococcus faecium strains from red wine. Food Microbiol. 2011, 28, 434–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, L.d.P.D.; Corich, V.; Jørgensen, E.G.; Devold, T.G.; Nadai, C.; Giacomini, A.; Porcellato, D. Potential bioactive peptides obtained after in vitro gastrointestinal digestion of wine lees from sequential fermentations. Food Res. Int. 2024, 176, 113833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, M.R.; Giovannitti, J.A. Histamine and histamine antagonists. In Pharmacology and Therapeutics for Dentistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, S. The management of compounds that influence human health in modern winemaking from an HACCP point of view. Fermentation 2019, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, F.; Montuori, P.; Schettino, M.; Velotto, S.; Stasi, T.; Romano, R.; Cirillo, T. Level of biogenic amines in red and white wines, dietary exposure, and histamine-mediated symptoms upon wine ingestion. Molecules 2019, 24, 3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirheimer, G.; Creppy, E.E. Mechanism of action of Ochratoxin A. IARC Sci. Publ. 1991, 115, 171–186. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC217510/ (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Kochman, J.; Jakubczyk, K.; Janda, K. Mycotoxins in red wine: Occurrence and risk assessment. Food Control 2021, 129, 108229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.J.G.; Rodrigues, A.P.; Pereira, A.M.P.T.; Lino, C.M.; Pena, A. Ochratoxin A in the Portuguese wine market, occurrence and risk assessment. Food Addit. Contam. B 2019, 12, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega, M.; Ríos, G.; von Baer, D.; Mardones, C.; Tessini, C.; Herlitz, E.; Saelzer, R.; Ruiz, M.A. Ochratoxin A occurrence in wines produced in Chile. Food Control 2012, 28, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otteneder, H.; Majerus, P. Occurrence of Ochratoxin A (OTA) in wines: Influence of the type of wine and its geographical origin. Food Addit. Contam. 2000, 17, 793–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, G.; De Girolamo, A.; Sarigiannis, Y.; Haidukowski, M.E.; Visconti, A. Occurrence of ochratoxin A, Fumonisin B2 and black Aspergilli in raisins from Western Greece regions in relation to environmental and geographical factors. Food Addit. Contam. A 2013, 30, 1339–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logrieco, A.; Ferracane, R.; Haidukowsky, M.; Cozzi, G.; Visconti, A.; Ritieni, A. Fumonisin B2 Production by Aspergillus niger from grapes and natural occurrence in must. Food Addit. Contam. A 2009, 26, 1495–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, R.T.; Merrill, A.H. Ceramide synthase inhibition by fumonisins: A perfect storm of perturbed sphingolipid metabolism, signaling, and disease. J. Lipid Res. 2019, 60, 1183–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logrieco, A.; Ferracane, R.; Visconti, A.; Ritieni, A. Natural occurrence of Fumonisin B2 in red wine from Italy. Food Addit Contam A 2010, 27, 1136–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mogensen, J.M.; Larsen, T.O.; Nielsen, K.F. Widespread occurrence of the mycotoxin Fumonisin B2 in wine. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 4853–4857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Air Quality Testing. Available online: https://verifyairqualitytest.ca/verify-air-quality-blog/f/mycotoxins-and-indoor-air-quality-what-you-need-to-know (accessed on 9 December 2024).

- Di Paolo, N.; Guarnieri, A.; Loi, F.; Sacchi, G.; Mangiarotti, A.M.; Di Paolo, M. Acute renal failure from inhalation of mycotoxins. Nephron 1993, 64, 621–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dündar, H. Bacteriocinogenic potential of Enterococcus faecium isolated from wine. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2016, 8, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, L.M.; Webb, A.K.; Limbago, B.; Dudeck, M.A.; Patel, J.; Kallen, A.J.; Edwards, J.R.; Sievert, D.M. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: Summary of data reported to the national healthcare safety network at the centers for disease control and prevention, 2011–2014. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2016, 37, 1288–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisiotou, A.A.; Rantsiou, K.; Iliopoulos, V.; Cocolin, L.; Nychas, G.-J.E. Bacterial species associated with sound and Botrytis-infected grapes from a Greek vineyard. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 145, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Multidrug-Resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, J.Y.; Yang, J.; Ko, J.-H.; Cho, S.Y.; Huh, K.; Chung, D.R.; Peck, K.R.; Ko, K.S.; Kang, C.-I. Extensively drug-resistant Enterobacter ludwigii co-harbouring MCR-9 and a multicopy of BlaIMP-1 in South Korea. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 36, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutsen, A.P.; Bush, R.K.; Demain, J.G.; Denning, D.W.; Dixit, A.; Fairs, A.; Greenberger, P.A.; Kariuki, B.; Kita, H.; Kurup, V.P.; et al. Fungi and allergic lower respiratory tract diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 129, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brera, C.; Caputi, R.; Miraglia, M.; Iavicoli, I.; Salerno, A.; Carelli, G. Exposure Assessment to mycotoxins in workplaces: Aflatoxins and ochratoxin A occurrence in airborne dusts and human sera. Microchem. J. 2002, 73, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, S.; Veiga, L.; Almeida, A.; dos Santos, M.; Carolino, E.; Viegas, C. Occupational exposure to Aflatoxin B1 in a Portuguese poultry slaughterhouse. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2016, 60, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youakim, S. Occupational health risks of wine industry workers. B C Med. J. 2006, 48, 386–391. [Google Scholar]

- Styles, O. The Dangerous Work of Making Wine. Available online: https://www.wine-searcher.com/m/2024/11/the-dangerous-work-of-making-wine?srsltid=AfmBOooBUa07Qnz9DBMeNi8H4CbAmNjVJ4tQadvvh6WF0cw9Y7pJwc-t (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Louis, F.; Guez, M.; Le Bâcle, C. Intoxication par inhalation de dioxyde de carbone. DMT 1999, 79, 179–194. [Google Scholar]

- Testud, F.; Matray, D.; Lambert, R.; Hillion, B.; Blanchet, C.; Teisseire, C.; Thibaudier, J.; Raoux, C.; Pacheco, Y. Respiratory symptoms after exposure to sulfurous anhydride in wine- cellar workers: Report of 6 cases. Rev. Mal. Respir. 2000, 17, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Tarara, J.M.; Lee, J.; Spayd, S.E.; Scagel, C.F. Berry temperature and solar radiation alter acylation, proportion, and concentration of anthocyanin in Merlot grapes. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2008, 59, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moukarzel, R.; Parker, A.K.; Schelezki, O.J.; Gregan, S.M.; Jordan, B. Bunch microclimate influence amino acids and phenolic profiles of Pinot Noir grape berries. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1162062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzamourani, A.; Evangelou, A.; Ntourtoglou, G.; Lytra, G.; Paraskevopoulos, I.; Dimopoulou, M. Effect of non-Saccharomyces species monocultures on alcoholic fermentation behavior and aromatic profile of Assyrtiko wine. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molitor, D.; Keller, M. Yield of Müller-Thurgau and Riesling grapevines is altered by meteorological conditions in the current and previous growing seasons. OENO One 2017, 50, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erasmus, D.J.; Cliff, M.; van Vuuren, H.J.J. Impact of yeast strain on the production of acetic acid, glycerol, and the sensory attributes of Icewine. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2004, 55, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labagnara, T.; Carrozza, G.; Toffanin, A. Biodiversity of wine yeast in response to environmental stress. Internet J. Enol. Vitic. 2014, 10/3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, M.G.; San Romão, M.V.; Loureiro-Dias, M.C.; Rombouts, F.M.; Abee, T. Flow cytometric assessment of membrane integrity of ethanol-stressed Oenococcus oeni cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 6087–6093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, J.A.; Payne, R.W.; Yarrow, D. Yeasts: Characteristics and Identification, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tofalo, R.; Rossetti, A.P.; Perpetuini, G. Climate change and wine quality. In Climate-Resilient Agriculture; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; Volume 1, pp. 157–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, A.; Vargas Soto, S.; Gambetta, G.; Schober, D.; Jeffers, E.; Coulson, T. Modelling the climate changing concentrations of key red wine grape quality molecules using a flexible modelling approach. OENO One 2024, 58, 8086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Escobar, R.; Aliaño-González, M.J.; Cantos-Villar, E. Variety and year: Two key factors on amino acids and biogenic amines content in grapes. Food Res. Int. 2024, 175, 113721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarca-Rivas, C.; Martín-Garcia, A.; Riu-Aumatell, M.; Bidon-Chanal, A.; López-Tamames, E. Effect of fermentation temperature on oenological parameters and volatile compounds in wine. BIO Web. Conf. 2023, 56, 02034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntuli, R.G.; Saltman, Y.; Ponangi, R.; Jeffery, D.W.; Bindon, K.; Wilkinson, K.L. Impact of fermentation temperature and grape solids content on the chemical composition and sensory profiles of Cabernet Sauvignon wines made from flash détente treated must fermented off-skins. Food Chem. 2022, 369, 130861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goelzer, A.; Charnomordic, B.; Colombié, S.; Fromion, V.; Sablayrolles, J.M. Simulation and optimization software for alcoholic fermentation in winemaking conditions. Food Control 2009, 20, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Antonio Gomez, C.; Manzano Agugliaro, F.; Ignacio Rojas Sola, J. Analysis of design criteria in authored wineries. Sci. Res. Essays 2011, 6, 4097–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facility Development Company (FDC). Available online: https://fdc-comp.com/services/winery-construction (accessed on 23 December 2024).

- Brown, D.C.; Turner, R.J. Assessing microbial monitoring methods for challenging environmental strains and cultures. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 13, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Celis, M.; Ruiz, J.; Vicente, J.; Acedo, A.; Marquina, D.; Santos, A.; Belda, I. Expectable diversity patterns in wine yeast communities. FEMS Yeast Res. 2022, 22, foac034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladin, Z.S.; Ferrell, B.; Dums, J.T.; Moore, R.M.; Levia, D.F.; Shriver, W.G.; D’Amico, V.; Trammell, T.L.E.; Setubal, J.C.; Wommack, K.E. Assessing the efficacy of eDNA metabarcoding for measuring microbial biodiversity within forest ecosystems. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, D.; Acharya, K.; Blackburn, A.; Zan, R.; Plaimart, J.; Allen, B.; Mgana, S.M.; Sabai, S.M.; Halla, F.F.; Massawa, S.M.; et al. MinIONNanopore sequencing accelerates progress towards ubiquitous genetics in water research. Water 2022, 14, 2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xufre, A.; Albergaria, H.; Inácio, J.; Spencer-Martins, I.; Gírio, F. Application of fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) to the analysis of yeast population dynamics in winery and laboratory grape must fermentations. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 108, 376–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, P.; Candeias, A.; Caldeira, A.T.; González-Pérez, M. An important step forward for the future development of an easy and fast procedure for identifying the most dangerous wine spoilage yeast, Dekkera bruxellensis, in wine environment. Microb. Biotechnol. 2019, 12, 1237–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares-Santos, V.; Pardo, I.; Ferrer, S. Improved detection and enumeration of yeasts in wine by Cells-qPCR. Lwt-Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 90, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mančić, S.; Stamenković Stojanović, S.; Danilović, B.; Djordjević, N.; Malićanin, M.; Lazić, M.; Karabegović, I. Oenological characterization of native Hanseniaspora uvarum strains. Fermentation 2022, 8, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Winery Type | RT (°C) | RH (%) | Micro-Organism | Concentration Mean (CFU or MNP per m3) | Concentration Range (CFU or MNP per m3) | Country [Reference] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old, modern and “Vin jeune” cellars | ~9.0–16.0 | 40–60 | Mesophilic molds Xerophilic molds | MEA: 665 MESA: 826 | MEA: 57–2422 MESA: 98–2547 | France [80] |

| Medium-sized winery | NR | NR | Brettanomyces | NR | BSE: 12–400 | USA [81] |

| Indoor processing facility | NR | NR | Bacteria Bacteria (Gram−) Fungi | NR NR NR | TSA: ~500–485,000 MCA: 0–180 MEA: ~200–146,000 | [79] |

| Old subterranean House-family Modern air-conditioned | ~9.0–13.0 NR ~9.5–15.3 | ~85–93 NR ~72–81 | Molds | MEA: 4769 MEA: 4293 MEA: 357 | MEA: 848–12,050 NR NR | Austria [82] |

| Winery (only red wines) | NR | NR | Molds Yeasts LAB | CZA: 500–10,000 CGA: 0–1000 MRS: 0–500 | Spain [75] | |

| Winery in La Rioja | NR | NR | LAB | MRS: 18 | MRS: 0–328 | Spain [61] |

| Brick and concrete wineries | 13.0–18.0 | 39–85 | Mesophilic molds Xerophilic molds | MEA: 1300 DG18: 1400 | MEA: 35–12,000 DG18: 110–14,000 | Austria [67] |

| Modern winery (four areas) in La Rioja | 10.3–23.5 | 45–86 | Molds | CZA: 2053 | CZA: 355–29,000 | Spain [83] |

| Three modern wineries (four areas) in La Rioja | NR | NR | Yeasts total Brettanomyces | CGA: NP DBDM: 1 | CGA: 0–180 DBDM: 0–18 | Spain [85] |

| Modern winery (four areas, 12 months) in La Rioja | NR | NR | Yeasts | CGA: 20 DBDM: 0 | CGA: 0–240 DBDM: 0 | Spain [84] |

| Winery (three areas, 2 years) in Castilla-La Mancha | NR | NR | Yeasts LAB | NR NR | CGA: 87–2300 MRS: <100–1800 | Spain [64] |

| Old (subterranean) and modern wine cellars | 13.7–17.7 | 52.4–89.5 | Molds | RBAC: 2788 MEA: NP | RBAC: 75–8190 MEA: NR | Hungary [73] |

| Underground cellar, covered by earth | 3.9–15.1 | 82–93 | Molds | NR | NR | Romania [87] |

| Winery Type | Micro-Organism Type | Dominant Group/Genera/Species (%) | Other Genera/Species (≤10%) | Reference | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Twelve wine cellars (Arbois region) | Molds | Penicillium, Cladosporium, Aspergillus | Botrytis cinerea, Zasmidium cellare, Emericella nidulans, Geotrichum, Mucor racemosus, Mycosphearella, Oidiodendron cereale, O. griseum, Spiniger meineckellus, Wardomyces inflatus | [80] | France |

| Old subterranean House-family Modern air-conditioned | Molds | Penicillium (77%), Aspergillus (15%) Penicillium (78%), Aspergillus (16%) Penicillium (50%), Aspergillus (20%) | Exophiala, Trichoderma - Clasdosporium, Phialophora, Phoma, Trichoderma, Ulocladium | [82] | Austria |

| Winery (pre-, during and post-harvest) | Molds Yeasts | Penicillium (20–80%), Aspergillus (10–50%), Botrytis (20–40%) Non-Saccharomyces (50–100%), Saccharomyces (20–100%) | - - | [75] | Spain |

| Winery (pre-, during and post-harvest) | LAB | Oenococcus oeni (15–100%) | Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Pediococcus pentosaceus | [61] | Spain |

| Thirty-six (2×) wine cellars (from 20 Styrian vintners) | Molds | Penicillium (45.1%), Aspergillus (20.5%), Cladosporium (11.5%) | Acremonium, Alternaria, Aureobasidium, Botrytis, Chrysonilia, Emericella, Epicoccum, Eurotium, Fusarium, Geotrichum, Moniliella, Mucor, Phanerochaete, Phoma, Rhizopus, Scopulariopsis, Schizophyllum, Stachybotrys, Trametes, Trichoderma, Trichothecium, Ulocladium, Wallemia | [67] | Austria |

| One winery (from February to December, in four places) | Molds | Penicillium (up to 90%), Aspergillus (up to 50%) | Alternaria, Botrytis, Clasdosporium, Fusarium, Paecillomyces, Trichoderma | [83] | Spain |

| Three wineries, 10–40 years old (over four seasons, in four places) | Yeasts | Cryptococus (23–73%), Aureobasidium (6–25%), Saccharomyces (6–10%), Sporidiobolus (1–16%) | Debaryomyces, Candida, Kloeckera, Pichia, Rhodotorula, Torulaspora, Sporobolomyces, Sporidiobolus, Bretanomyces, Arthroascus | [85] | Spain |

| One winery (from February 2008 to January 2009) in four areas (cask and bottle aging cellars, vinification and bottling) | Yeasts | Cryptococcus (30.3%), Sporidiobolus (20.1%), Aureobasidium (12.1%) | Candida, Debaryomyces, Williopsis, Rhodotorula, Pichia, Sporobolomyces, Saccharomyces, Bullera, Torulaspora | [84] | Spain |

| One winery (over 2 years, in three places, one season per year) | LAB | L. mesenteroides (31–56%), Pediococcus acidilactici (0–29%), O. oeni (0–24%), Lactobacillus casei/paracasei (1–24%), Lactobacillus plantarum (0–11%) | Enterococcus sp., Lentilactobacillus hilgardii Lactococcus lactis spp. hordniae, Lactobacillus brevis, Lactobacillus fermentum | [64] | Spain |

| Yeasts | Saccharomyces cerevisiae (87–89%) | Torulaspora delbrueckii, Hanseniaspora uvarum/guilliermondii, Cryptococus flavescens, Pichia anomala, Candida norvegica | |||

| Winery with GMP | Bacteria | Micrococcus luteus (67.4%), Kytococcus sedentarius (12.3%) | Aerococcus, Brevibacillus, Bacillus, Corynebacterium, Leuconostoc, Lactococcus, Pediococcus, Staphylococcus, Streptococcus | [86] | Malaysia |

| Five traditional and subterranean wine cellars (Tokaj wine district) | Molds Yeasts | Penicillium, Rasamsonia, Talaromyces and Aspergillus Yeasts not identified | Alternaria, Aphanocladium, Aspergillus, Botrytis cinerea, Clasdosporium, Emericella nidulans, Epicoccum, Mucor, Scopulariopsis, Zasmidium cellare Candida membranifaciens, Debaryomyces subglobosus | [73] | Hungary |

| One traditional wine cellar (in Sălacea), between April and May 2018 | Molds | Cladosporium, Penicillium, Aspergillus, | Trichoderma, Ulocladium, Geotrichum, Fusarium, Alternaria | [87] | Romania |

| Metabolites/Micro-Organism | Taxa (Group/Genus/Species) | Health Issues |

|---|---|---|

| Biogenic amines (e.g., histamine, tyramine, putrescine, cadaverine) | LAB, some yeasts, S. epidermis, E. faecium | Allergenic, vasoactive, psychoactive effects |

| Aflatoxins, ochratoxin A | Aspergillus (A. carbonarius, A. fumigatus, A. niger, A. tubingensis, A. japonicus, A. welwistichiae), Penicillium | Carcinogenic, genotoxic, immunotoxic, hepatotoxic |

| Alternariol | Alternaria (A. alternata), B. cinerea | Mutagenic, carcinogenic |

| Fumonisins | Fusarium (F. verticillioides, F. oxysporum), A. niger, A. welwitschiae | Disrupt sphingolipid biosynthesis (inhibition of ceramide synthase) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aires, C.; Maioto, R.; Inês, A.; Dias, A.A.; Rodrigues, P.; Egas, C.; Sampaio, A. Microbiome and Microbiota Within Wineries: A Review. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13030538

Aires C, Maioto R, Inês A, Dias AA, Rodrigues P, Egas C, Sampaio A. Microbiome and Microbiota Within Wineries: A Review. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(3):538. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13030538

Chicago/Turabian StyleAires, Cristina, Rita Maioto, António Inês, Albino Alves Dias, Paula Rodrigues, Conceição Egas, and Ana Sampaio. 2025. "Microbiome and Microbiota Within Wineries: A Review" Microorganisms 13, no. 3: 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13030538

APA StyleAires, C., Maioto, R., Inês, A., Dias, A. A., Rodrigues, P., Egas, C., & Sampaio, A. (2025). Microbiome and Microbiota Within Wineries: A Review. Microorganisms, 13(3), 538. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13030538