The Global Trends and Advances in Oral Microbiome Research on Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

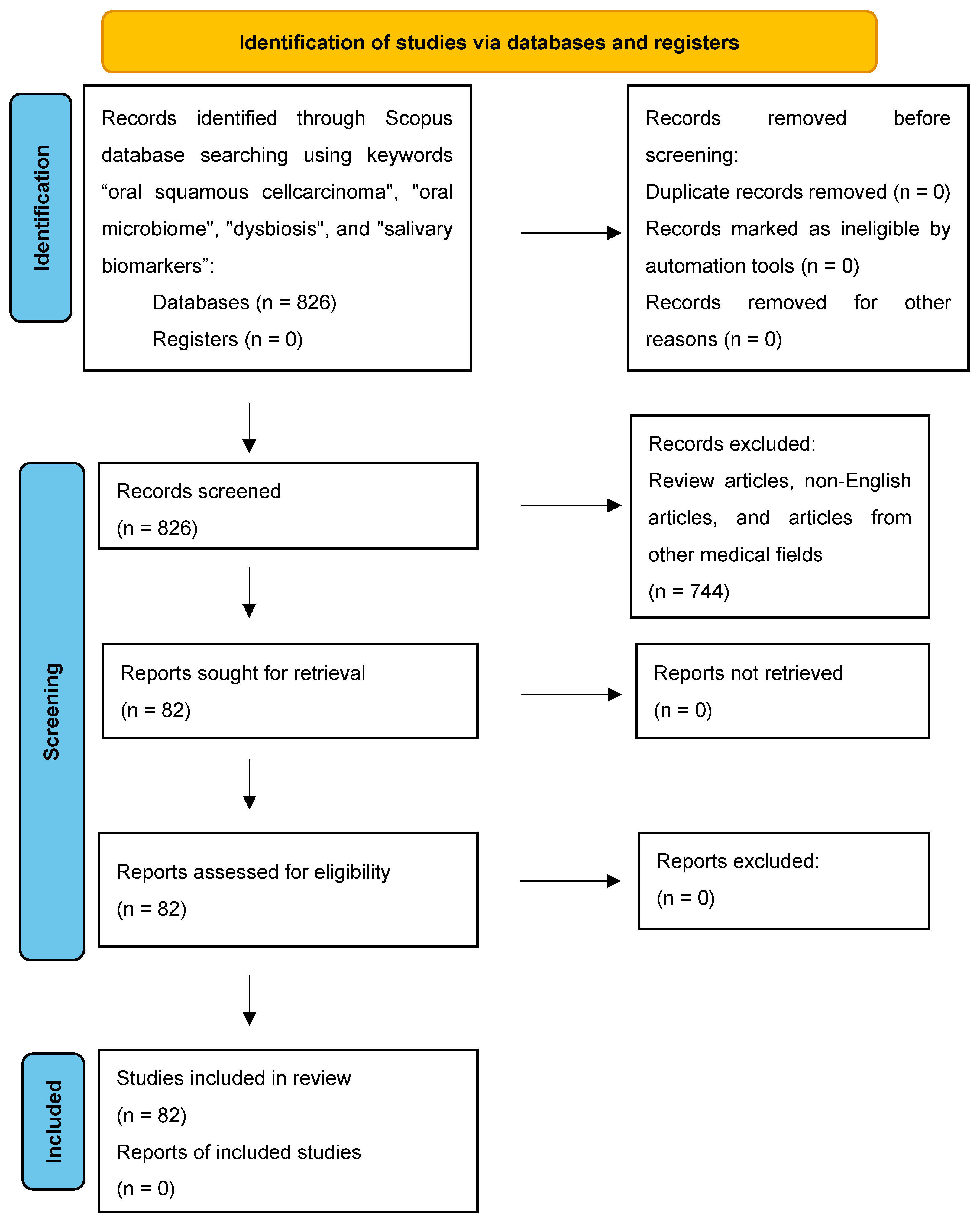

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources, Collection, and Processing

2.2. Risk of Bias

2.3. Bibliometric Analysis

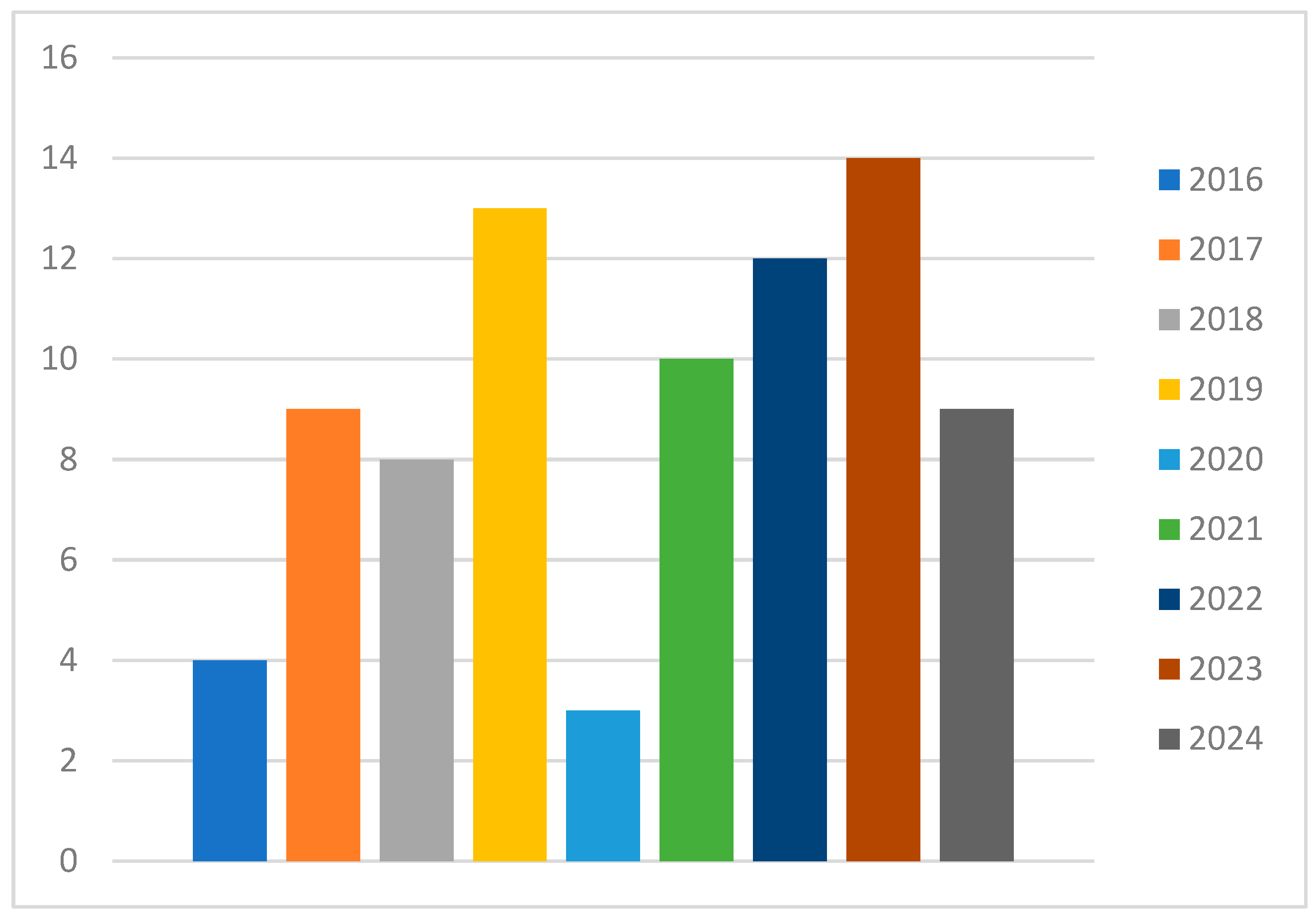

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection, Data Extraction, and Risk of Bias

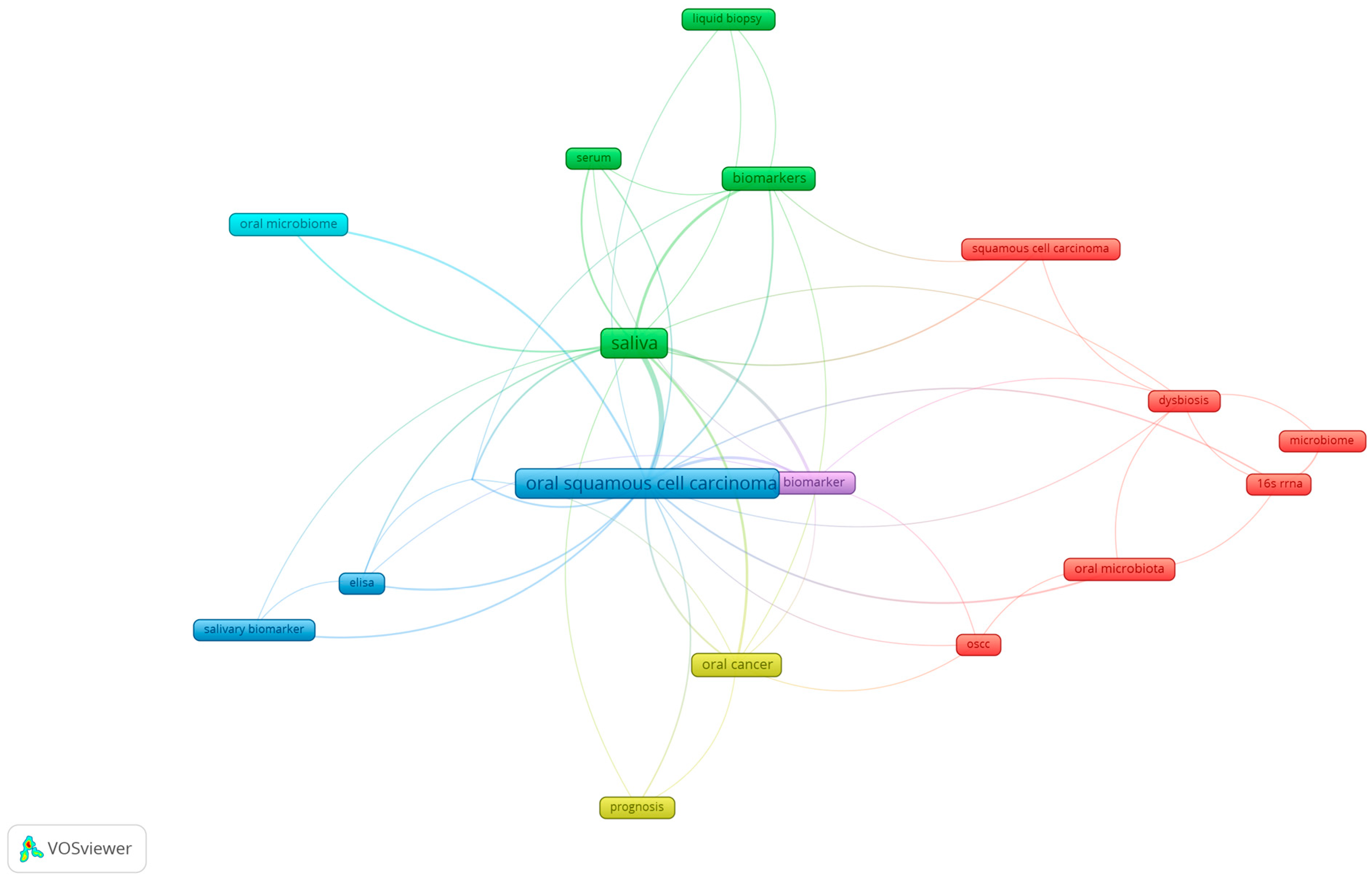

3.2. Keyword Analysis of Research Themes in Oral Microbiome and Oral Cancer

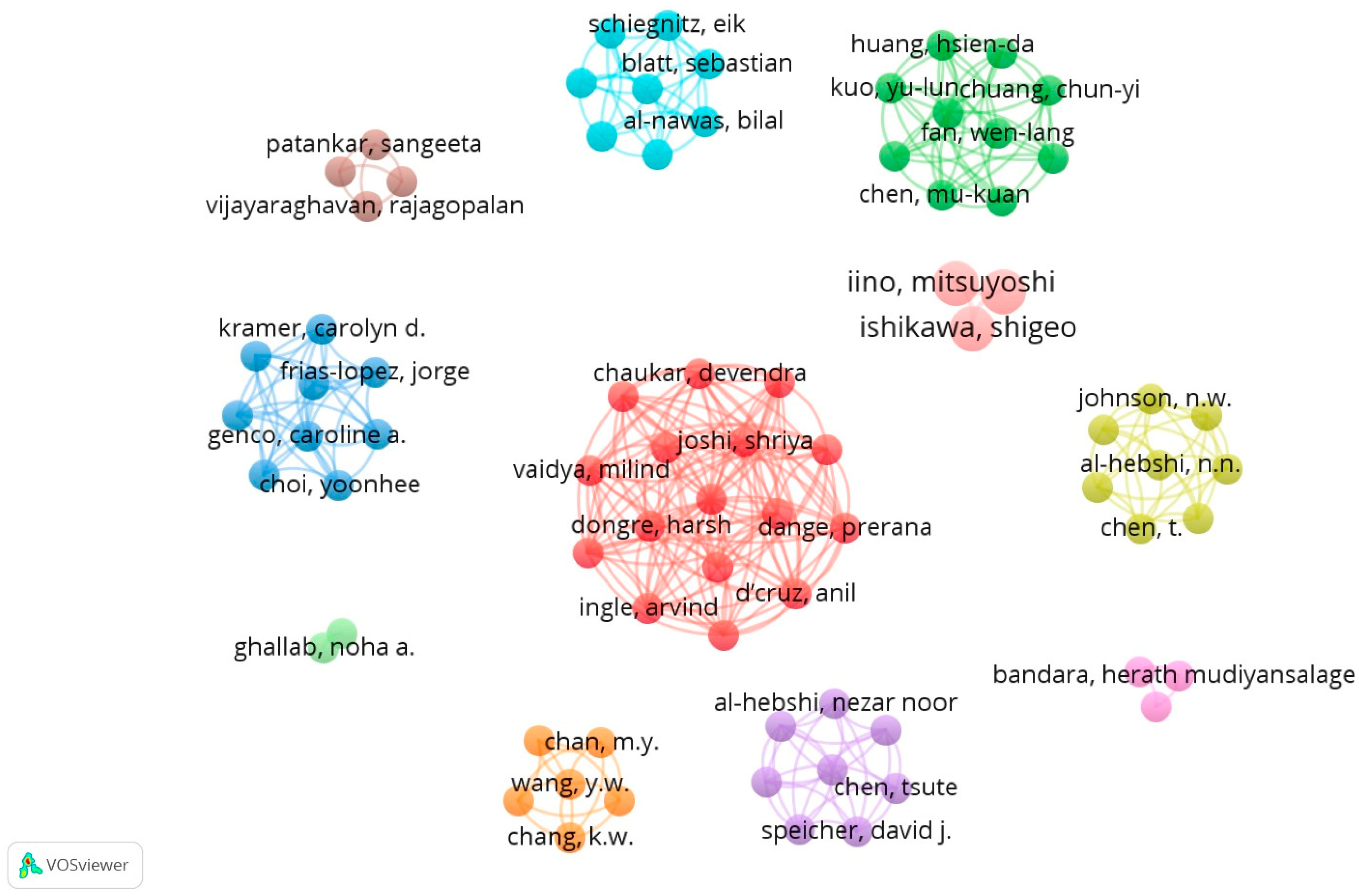

3.3. Analysis of “Co-Authorship” in Terms of Number of Citations

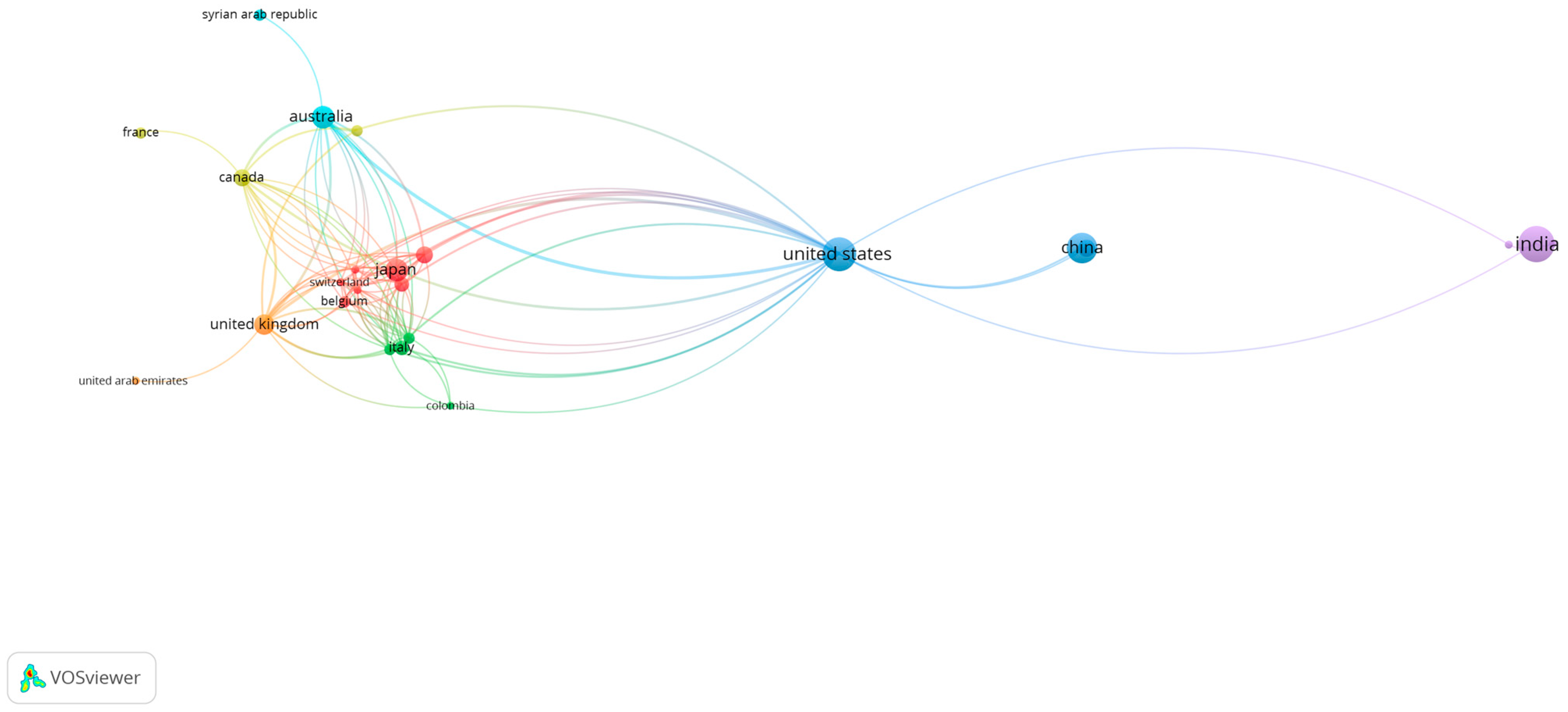

3.4. Analysis of International Co-Authorship Networks in Scientific Research

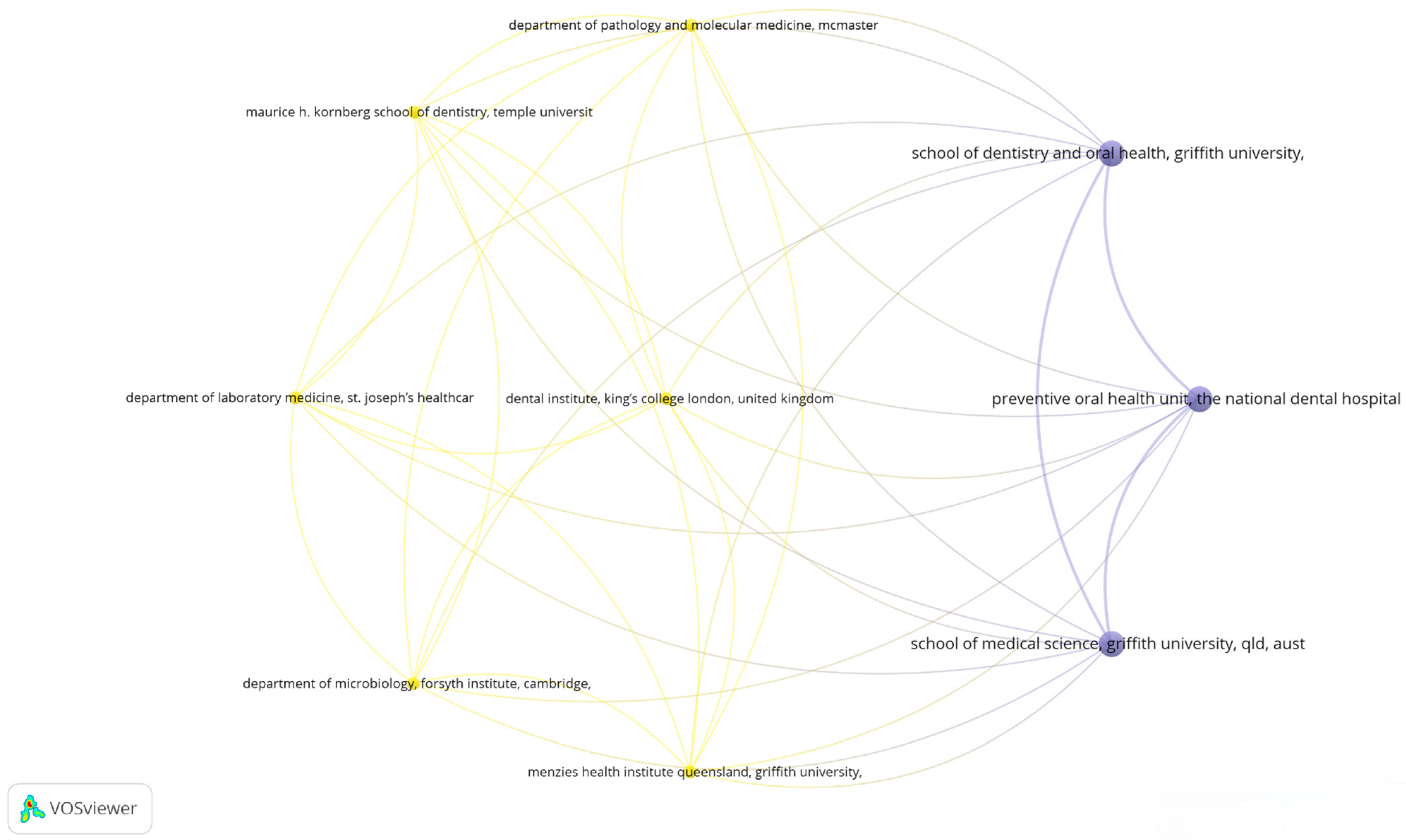

3.5. Visualizing Collaborative Networks in Dental Research: A Co-Authorship Bibliometric Analysis of Key Organizations

3.6. Exploring Co-Occurrence Relationships: Insights from Oral Microbiome Research

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deo, P.; Deshmukh, R. Oral Microbiome: Unveiling the Fundamentals. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2019, 23, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotti, E.; Boué, S.; Sasso, G.L.; Zanetti, F.; Belcastro, V.; Poussin, C.; Sierro, N.; Battey, J.; Gimalac, A.; Ivanov, N.V.; et al. Exploring the Microbiome in Health and Disease: Implications for Toxicology. Toxicol. Res. Appl. 2017, 1, 239784731774188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Xu, T.; Huang, G.; Jiang, S.; Gu, Y.; Chen, F. Oral Microbiomes: More and More Importance in Oral Cavity and Whole Body. Protein Cell 2018, 9, 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, B.; Faustoferri, R.C.; Quivey, R.G. What Are We Learning and What Can We Learn from the Human Oral Microbiome Project? Curr. Oral Health Rep. 2016, 3, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Luo, J.; Dong, X.; Zhao, S.; Hao, Y.; Peng, C.; Shi, H.; Zhou, Y.; Shan, L.; Sun, Q.; et al. Salivary Microbial Dysbiosis Is Associated with Systemic Inflammatory Markers and Predicted Oral Metabolites in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Patients. J. Cancer 2019, 10, 1651–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Bai, H.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, X.; Ying, B. Promising Applications of Human-Derived Saliva Biomarker Testing in Clinical Diagnostics. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2023, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.-Z.; Cheng, X.-Q.; Li, J.-Y.; Zhang, P.; Yi, P.; Xu, X.; Zhou, X.-D. Saliva in the Diagnosis of Diseases. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2016, 8, 133–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, C.; Balean, O.; Dumitrescu, R.; Ciordas, P.D.; Marian, C.; Georgescu, M.; Bolchis, V.; Sava-Rosianu, R.; Fratila, A.D.; Alexa, I.; et al. Total Antioxidant Capacity of Saliva and Its Correlation with pH Levels among Dental Students under Different Stressful Conditions. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Q.; Zhang, C.; Hua, H.; Hu, X. Compositional and Functional Changes in the Salivary Microbiota Related to Oral Leukoplakia and Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Case Control Study. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, N.A.J.; Vardhan, B.G.H.; Srinivasan, S.; Gopal, S.K. Evaluation of Salivary Interleukin-6 in Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders, Chronic Periodontitis and in Healthy Controls—A Cross-Sectional Comparative Study. Ann. Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 13, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavakoli, F.; Ghavimi, M.A.; Fakhrzadeh, V.; Abdolzadeh, D.; Afshari, A.; Eslami, H. Evaluation of Salivary Transferrin in Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2024, 10, e809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radhika, T.; Jeddy, N.; Nithya, S.; Muthumeenakshi, R.M. Salivary Biomarkers in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma—An Insight. J. Oral Biol. Craniofacial Res. 2016, 6, S51–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shield, K.D.; Ferlay, J.; Jemal, A.; Sankaranarayanan, R.; Chaturvedi, A.K.; Bray, F.; Soerjomataram, I. The Global Incidence of Lip, Oral Cavity, and Pharyngeal Cancers by Subsite in 2012. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, M.; Nair, R.; Jamieson, L.; Liu, Z.; Bi, P. Incidence Trends of Lip, Oral Cavity, and Pharyngeal Cancers: Global Burden of Disease 1990–2017. J. Dent. Res. 2020, 99, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Hu, C.; He, H.; Li, Y.; Lyu, J. Global and Regional Burdens of Oral Cancer from 1990 to 2017: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Cancer Commun. 2020, 40, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuanbo, Z.; Tianyi, L.; Xuejing, S.; Xinpeng, L.; Jianqun, W.; Wenxia, X.; Jingshu, G. Using Formalin Fixed Paraffin Embedded Tissue to Characterize the Microbiota in P16-Positive and P16-Negative Tongue Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Pilot Study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.; Fiscella, K.A.; Gill, S.R. Oral Microbiome: Possible Harbinger for Children’s Health. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2020, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, L.; Yang, X. Bibliometric Analysis of Research Trends and Characteristics of Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders. Clin. Oral Investig. 2020, 24, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassona, Y.; Qutachi, T. A Bibliometric Analysis of the Most Cited Articles about Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Mouth, Lips, and Oropharynx. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2019, 128, 25–32.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pena-Cristóbal, M.; Diniz-Freitas, M.; Monteiro, L.; Diz Dios, P.; Warnakulasuriya, S. The 100 Most Cited Articles on Oral Cancer. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2018, 47, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, I.D. Bibliometrics Basics. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2015, 103, 217–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, A.K.; Panda, M.; Das, A.K.; Rahman, T.; Das, R.; Das, K.; Sarma, A.; Kataki, A.C.; Chattopadhyay, I. Dysbiosis of Salivary Microbiome and Cytokines Influence Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma through Inflammation. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bugshan, A.; Farooq, I. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Metastasis, Potentially Associated Malignant Disorders, Etiology and Recent Advancements in Diagnosis. F1000Research 2020, 9, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Moles, M.Á.; Warnakulasuriya, S.; González-Ruiz, I.; González-Ruiz, L.; Ayén, Á.; Lenouvel, D.; Ruiz-Ávila, I.; Ramos-García, P. Worldwide Prevalence of Oral Lichen Planus: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2021, 27, 813–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibliometrics & Verification|Karolinska Institutet University Library. Available online: https://kib.ki.se/en/publish-analyse/bibliometrics-verification (accessed on 26 May 2024).

- Zyoud, S.H.; Al-Jabi, S.W.; Amer, R.; Shakhshir, M.; Shahwan, M.; Jairoun, A.A.; Akkawi, M.; Abu Taha, A. Global Research Trends on the Links between the Gut Microbiome and Cancer: A Visualization Analysis. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Chang, C.; Chen, X.; Li, K. Emerging Trends and Focus of Human Gastrointestinal Microbiome Research from 2010–2021: A Visualized Study. J. Transl. Med. 2021, 19, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Page, M.J.; Pritchard, C.C.; McGuinness, L.A. PRISMA2020: An R Package and Shiny App for Producing PRISMA 2020-compliant Flow Diagrams, with Interactivity for Optimised Digital Transparency and Open Synthesis. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2022, 18, e1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, L.A.; Higgins, J.P.T. Risk-of-bias VISualization (Robvis): An R Package and Shiny Web App for Visualizing Risk-of-bias Assessments. Res. Synth. Methods 2021, 12, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Citation-Based Clustering of Publications Using CitNetExplorer and VOSviewer. Scientometrics 2017, 111, 1053–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Gupta, R.; Acharya, A.K.; Patthi, B.; Goud, V.; Reddy, S.; Garg, A.; Singla, A. Changing Trends in Oral Cancer—A Global Scenario. Nepal J. Epidemiol. 2017, 6, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minarovits, J. Anaerobic Bacterial Communities Associated with Oral Carcinoma: Intratumoral, Surface-Biofilm and Salivary Microbiota. Anaerobe 2021, 68, 102300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.A.; Sborchia, M.; Bye, H.; Roman-Escorza, M.; Amar, A.; Henley-Smith, R.; Odell, E.; McGurk, M.; Simpson, M.; Ng, T.; et al. Mutation Detection in Saliva from Oral Cancer Patients. Oral Oncol. 2024, 151, 106717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapado-González, Ó.; Costa-Fraga, N.; Bao-Caamano, A.; López-Cedrún, J.L.; Álvarez-Rodríguez, R.; Crujeiras, A.B.; Muinelo-Romay, L.; López-López, R.; Díaz-Lagares, Á.; Suárez-Cunqueiro, M.M. Genome-Wide DNA Methylation Profiling in Tongue Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oral Dis. 2024, 30, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheurer, M.J.J.; Wagner, A.; Sakkas, A.; Pietzka, S.; Derka, S.; Vairaktari, G.; Wilde, F.; Schramm, A.; Bauer, A.; Siebert, R.; et al. Influence of Analytical Procedures on miRNA Expression Analyses in Saliva Samples. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 52, 748–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Shen, W.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Zhai, R.; Zhang, J.; Wang, M.; Wang, M.; Liu, L. Capnocytophaga Gingivalis Is a Potential Tumor Promotor in Oral Cancer. Oral Dis. 2024, 30, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riccardi, G.; Bellizzi, M.G.; Fatuzzo, I.; Zoccali, F.; Cavalcanti, L.; Greco, A.; Vincentiis, M.D.; Ralli, M.; Fiore, M.; Petrella, C.; et al. Salivary Biomarkers in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Proteomic Overview. Proteomes 2022, 10, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhadian, S.; Hashemi-Shahraki, F.; Amirifar, S.; Asadpour, S.; Shareghi, B.; Heidari, E.; Shakerian, B.; Rafatifard, M.; Firooz, A.R. Malachite Green, the Hazardous Materials That Can Bind to Apo-Transferrin and Change the Iron Transfer. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 194, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.Y.; Chen, J.W.; Wu, L.W.; Huang, K.C.; Chen, J.Y.; Wu, W.S.; Chiang, W.F.; Shih, C.J.; Tsai, K.N.; Hsieh, W.T.; et al. Carcinogenesis of Male Oral Submucous Fibrosis Alters Salivary Microbiomes. J. Dent. Res. 2021, 100, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herreros-Pomares, A.; Hervás, D.; Bagan-Debón, L.; Jantus-Lewintre, E.; Gimeno-Cardona, C.; Bagan, J. On the Oral Microbiome of Oral Potentially Malignant and Malignant Disorders: Dysbiosis, Loss of Diversity, and Pathogens Enrichment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganly, I.; Yang, L.; Giese, R.A.; Hao, Y.; Nossa, C.W.; Morris, L.G.T.; Rosenthal, M.; Migliacci, J.; Kelly, D.; Tseng, W.; et al. Periodontal Pathogens Are a Risk Factor of Oral Cavity Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Independent of Tobacco and Alcohol and Human Papillomavirus. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 145, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K.; Shimizu, D.; Ueda, S.; Miyabe, S.; Oh-Iwa, I.; Nagao, T.; Shimozato, K.; Nomoto, S. Feasibility of Oral Microbiome Profiles Associated with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Oral Microbiol. 2022, 14, 2105574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Wang, L.; Ma, D.; Zhang, H.; Fan, J.; Gao, H.; Xia, X.; Wu, W.; Shi, Y. miR-19a May Function as a Biomarker of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC) by Regulating the Signaling Pathway of miR-19a/GRK6/GPCRs/PKC in a Chinese Population. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2023, 52, 971–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, D.; Jose, J.; Harish Kumar, A. Is Salivary Sialic Acid a Reliable Biomarker in the Detection of Oral Potentially Malignant Disorder and Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2021, 20, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yap, T.; Seers, C.; Koo, K.; Cheng, L.; Vella, L.J.; Hill, A.F.; Reynolds, E.; Nastri, A.; Cirillo, N.; McCullough, M. Non-Invasive Screening of a microRNA-Based Dysregulation Signature in Oral Cancer and Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders. Oral Oncol. 2019, 96, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, J.; Sun, L.; Yuan, W.; Xu, J.; Yu, X.; Wang, F.; Sun, L.; Zeng, Y. Clinical Value of Naa10p and CEA Levels in Saliva and Serum for Diagnosis of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2018, 47, 830–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hes, C.; Desilets, A.; Tonneau, M.; El Ouarzadi, O.; De Figueiredo Sousa, M.; Bahig, H.; Filion, É.; Nguyen-Tan, P.F.; Christopoulos, A.; Benlaïfaoui, M.; et al. Gut Microbiome Predicts Gastrointestinal Toxicity Outcomes from Chemoradiation Therapy in Patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2024, 148, 106623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdipour, M.; Shahidi, M.; Anbari, F.; Mirzaei, H.; Jafari, S.; Kholghi, A.; Lotfi, E.; Manifar, S.; Mashhadiabbas, F. Salivary Level of microRNA-146a and microRNA-155 Biomarkers in Patients with Oral Lichen Planus versus Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapado-González, Ó.; López-Cedrún, J.L.; Lago-Lestón, R.M.; Abalo, A.; Rubin-Roger, G.; Salgado-Barreira, Á.; López-López, R.; Muinelo-Romay, L.; Suárez-Cunqueiro, M.M. Integrity and Quantity of Salivary Cell-Free DNA as a Potential Molecular Biomarker in Oral Cancer: A Preliminary Study. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2022, 51, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menaka, T.R.; Vasupradha, G.; Ravikumar, S.S.; Dhivya, K.; Dinakaran, J.; Saranya, V. Evaluation of Salivary Alkaline Phosphatase Levels in Tobacco Users to Determine Its Role as a Biomarker in Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2019, 23, 344–348. [Google Scholar]

- Sridharan, G.; Ramani, P.; Patankar, S.; Vijayaraghavan, R. Evaluation of Salivary Metabolomics in Oral Leukoplakia and Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2019, 48, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandara, H.M.H.N.; Panduwawala, C.P.; Samaranayake, L.P. Biodiversity of the Human Oral Mycobiome in Health and Disease. Oral Dis. 2019, 25, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palaia, G.; Pippi, R.; Rocchetti, F.; Caputo, M.; Macali, F.; Mohsen, A.; Vecchio, A.D.; Tenore, G.; Romeo, U. Liquid Biopsy in the Assessment of microRNAs in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2022, 14, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afifi, S.; Zahran, F.; Shaker, O.; Tarrad, N.; Elsaadany, B. Sensitivity and Specificity of Serum and Salivary Cyfra21-1 in Detecting Malignant Changes in Oral Potentially Malignant Lesions (Diagnostic Accuracy Study). World J. Dent. 2021, 12, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.; Shetti, A.V.; Bagewadi, A.S. Assessment and Comparison of Salivary Survivin Biomarker in Oral Leukoplakia, Oral Lichen Planus, and Oral Cancer: A Comparative Study. World J. Dent. 2017, 8, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, M.; Al-hebshi, N.N.; Perera, I.; Ipe, D.; Ulett, G.C.; Speicher, D.J.; Chen, T.; Johnson, N.W. Inflammatory Bacteriome and Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Dent. Res. 2018, 97, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farshbaf, A.; Mohajertehran, F.; Aghaee-Bakhtiari, S.H.; Ayatollahi, H.; Douzandeh, K.; Pakfetrat, A.; Mohtasham, N. Downregulation of Salivary miR-3928 as a Potential Biomarker in Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Oral Lichen Planus. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2024, 10, e877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosratzehi, T.; Risbaf Fakour, S.; Alijani, E.; Salehi, M. Investigating the Level of Salivary Endothelin-1 in Premalignant and Malignant Lesions. Spec. Care Dentist. 2017, 37, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vesty, A.; Gear, K.; Biswas, K.; Radcliff, F.J.; Taylor, M.W.; Douglas, R.G. Microbial and Inflammatory-Based Salivary Biomarkers of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2018, 4, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blatt, S.; Krüger, M.; Ziebart, T.; Sagheb, K.; Schiegnitz, E.; Goetze, E.; Al-Nawas, B.; Pabst, A.M. Biomarkers in Diagnosis and Therapy of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Review of the Literature. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 45, 722–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, Z.; Shaikh, A.H.; Zaman, U.; Ahmed, S.; Majeed, M.M.; Kazmi, A.; Farooqui, W.A. Estimation of Salivary Matrix Metalloproteinases- 12 (MMP- 12) Levels among Patients Presenting with Oral Submucous Fibrosis and Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, e87721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrad, N.A.F.; Hassan, S.; Shaker, O.G.; AbdelKawy, M. “Salivary LINC00657 and miRNA-106a as Diagnostic Biomarkers for Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma, an Observational Diagnostic Study”. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, E.R.; Reis, I.M.; Gomez-Fernandez, C.; Smith, D.; Pereira, L.; Freiser, M.E.; Marotta, G.; Thomas, G.R.; Sargi, Z.B.; Franzmann, E.J. CD44 and Associated Markers in Oral Rinses and Tissues from Oral and Oropharyngeal Cancer Patients. Oral Oncol. 2020, 106, 104720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajaram, S.; Danasekaran, B.; Venkatachalapathy, R.; Prashad, K.; Rajaram, S. N-Acetylneuraminic Acid: A Scrutinizing Tool in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Diagnosis. Dent. Res. J. 2017, 14, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, N.; Hashida, Y.; Higuchi, T.; Ohno, S.; Sento, S.; Sasabe, E.; Murakami, I.; Yamamoto, T.; Daibata, M. Detection of Merkel Cell Polyomavirus in Multiple Primary Oral Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Odontology 2023, 111, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaba, F.I.; Sheth, C.C.; Veses, V. Salivary Biomarkers and Their Efficacies as Diagnostic Tools for Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2021, 50, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.-S.L.; Jordan, L.; Chen, H.-S.; Kang, D.; Oxford, L.; Plemons, J.; Parks, H.; Rees, T. Chronic Periodontitis Can Affect the Levels of Potential Oral Cancer Salivary mRNA Biomarkers. J. Periodontal Res. 2017, 52, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabbir, A.; Waheed, H.; Ahmed, S.; Shaikh, S.S.; Farooqui, W.A. Association of Salivary Cathepsin B in Different Histological Grades among Patients Presenting with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. BMC Oral Health 2022, 22, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougeot, J.-L.C.; Stevens, C.B.; Almon, K.G.; Paster, B.J.; Lalla, R.V.; Brennan, M.T.; Mougeot, F.B. Caries-Associated Oral Microbiome in Head and Neck Cancer Radiation Patients: A Longitudinal Study. J. Oral Microbiol. 2019, 11, 1586421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, S.; Sugimoto, M.; Edamatsu, K.; Sugano, A.; Kitabatake, K.; Iino, M. Discrimination of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma from Oral Lichen Planus by Salivary Metabolomics. Oral Dis. 2020, 26, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiuch, K.; Bednarczyk, A.; Gawlik, K.; Pawlica-Gosiewska, D.; Kęsek, B.; Darczuk, D.; Stępień, P.; Chomyszyn-Gajewska, M.; Kaczmarzyk, T. Evaluation of Enzymatic and Non-Enzymatic Antioxidant Status and Biomarkers of Oxidative Stress in Saliva of Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Oral Leukoplakia: A Pilot Study. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2019, 77, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, J.; Sun, Z.; Yang, J.; Xu, J.; Shi, W.; Wu, Y.; Fan, Y.; Li, H. Discovery and Preclinical Validation of Proteomic Biomarkers in Saliva for Early Detection of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Oral Dis. 2019, 25, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katase, N.; Kudo, K.; Ogawa, K.; Sakamoto, Y.; Nishimatsu, S.; Yamauchi, A.; Fujita, S. DKK3/CKAP4 Axis Is Associated with Advanced Stage and Poorer Prognosis in Oral Cancer. Oral Dis. 2023, 29, 3193–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelwhab, A.; Shaker, O.; Aggour, R.L. Expression of Mucin1 in Saliva in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders (Case Control Study). Oral Dis. 2023, 29, 1487–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallalli, B.N.; Rawson, K.; Muzammil; Singh, A.; Awati, M.A.; Shivhare, P. Lactate Dehydrogenase as a Biomarker in Oral Cancer and Oral Submucous Fibrosis. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2016, 45, 687–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapple, I.L.C.; Mealey, B.L.; Van Dyke, T.E.; Bartold, P.M.; Dommisch, H.; Eickholz, P.; Geisinger, M.L.; Genco, R.J.; Glogauer, M.; Goldstein, M.; et al. Periodontal Health and Gingival Diseases and Conditions on an Intact and a Reduced Periodontium: Consensus Report of Workgroup 1 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, S74–S84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolivet-Gougeon, A.; Bonnaure-Mallet, M. Screening for Prevalence and Abundance of Capnocytophaga Spp by Analyzing NGS Data: A Scoping Review. Oral Dis. 2021, 27, 1621–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, S.; Wong, D.T.W.; Sugimoto, M.; Gleber-Netto, F.O.; Li, F.; Tu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Akin, D.; Iino, M. Identification of Salivary Metabolites for Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Oral Epithelial Dysplasia Screening from Persistent Suspicious Oral Mucosal Lesions. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019, 23, 3557–3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banavar, G.; Ogundijo, O.; Julian, C.; Toma, R.; Camacho, F.; Torres, P.J.; Hu, L.; Chandra, T.; Piscitello, A.; Kenny, L.; et al. Detecting Salivary Host and Microbiome RNA Signature for Aiding Diagnosis of Oral and Throat Cancer. Oral Oncol. 2023, 145, 106480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, X.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; He, Y.; Wei, W.; Wang, Y. Oral Microbiota Alteration Associated with Oral Cancer and Areca Chewing. Oral Dis. 2021, 27, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.; Zraiki, S.; Khayat, M. Evaluation of the Salivary Zinc Assay as a Potential Diagnostic Tool in Potential Malignant and Malignant Lesions of the Oral Cavity. J. Indian Acad. Oral Med. Radiol. 2019, 31, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chari, A.; Rajesh, P.; Prabhu, S. Estimation of Serum Lactate Dehydrogenase in Smokeless Tobacco Consumers. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2016, 27, 602–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayal, L.; Hamadah, O.; Almasri, A.; Idrees, M.; Thomson, P.; Kujan, O. Saliva-Based Cell-Free DNA and Cell-Free Mitochondrial DNA in Head and Neck Cancers Have Promising Screening and Early Detection Role. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2023, 52, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameena, M.; Rathy, R. Evaluation of Tumor Necrosis Factor: Alpha in the Saliva of Oral Cancer, Leukoplakia, and Healthy Controls—A Comparative Study. J. Int. Oral Health 2019, 11, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yost, S.; Stashenko, P.; Choi, Y.; Kukuruzinska, M.; Genco, C.A.; Salama, A.; Weinberg, E.O.; Kramer, C.D.; Frias-Lopez, J. Increased Virulence of the Oral Microbiome in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Revealed by Metatranscriptome Analyses. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2018, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, J.; Yi, P.; Xu, X.; Fan, Y.; Cui, B.; Yu, Y.; Li, X.; Du, Y.; et al. Salivary Protease Spectrum Biomarkers of Oral Cancer. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2019, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghallab, N.A.; Shaker, O.G. Serum and Salivary Levels of Chemerin and MMP-9 in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Oral Premalignant Lesions. Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 21, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawant, S.; Gokulan, R.; Dongre, H.; Vaidya, M.; Chaukar, D.; Prabhash, K.; Ingle, A.; Joshi, S.; Dange, P.; Joshi, S.; et al. Prognostic Role of Oct4, CD44 and c-Myc in Radio–Chemo-Resistant Oral Cancer Patients and Their Tumourigenic Potential in Immunodeficient Mice. Clin. Oral Investig. 2016, 20, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.T.; Wong, Y.K.; Hsiao, H.Y.; Wang, Y.W.; Chan, M.Y.; Chang, K.W. Evaluation of Saliva and Plasma Cytokine Biomarkers in Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 47, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triani, M.; Widodo, H.B.; Novrial, D.; Agustina, D.; Nawangtantrini, G. Salivary Ki-67 and Micronucleus Assay as Potential Biomarker of OSCC in Betel Nut Chewers. J. Indian Acad. Oral Med. Radiol. 2021, 33, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, M.; Al-Hebshi, N.N.; Perera, I.; Ipe, D.; Ulett, G.C.; Speicher, D.J.; Chen, T.; Johnson, N.W. A Dysbiotic Mycobiome Dominated by Candida Albicans Is Identified within Oral Squamous-Cell Carcinomas. J. Oral Microbiol. 2017, 9, 1385369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, J.Y.K.; Cheung, M.K.; Lan, L.; Ng, C.; Lau, E.H.L.; Yeung, Z.W.C.; Wong, E.W.Y.; Leung, L.; Qu, X.; Cai, L.; et al. Characterization of Oral Microbiota in HPV and Non-HPV Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Its Association with Patient Outcomes. Oral Oncol. 2022, 135, 106245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, J.; Politis, C.; Jacobs, R. Salivary 8-Hydroxy-2-Deoxyguanosine, Malondialdehyde, Vitamin C, and Vitamin E in Oral Pre-Cancer and Cancer: Diagnostic Value and Free Radical Mechanism of Action. Clin. Oral Investig. 2016, 20, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumaran, J.; Ramesh, V.; Daniel, M. Salivary Micrornas (miRNAs) Expression and Its Implications as Biomarkers in Oral Cancer. J. Indian Acad. Oral Med. Radiol. 2022, 34, 475–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, H.; Gunasekaran, N.; James, A.; Krishnan, R.; Thayalan, D.; Kumar, A. Alpha-L-Fucosidase Levels in Patients with Oral Submucous Fibrosis and Controls: A Comparative Study. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2022, 26, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrazzo, K.L.; De Melo, L.D.W.; Danesi, C.C.; Thomas, A.; Bonzanini, L.I.L.; Zanatta, N. Sensitivity and Specificity of Salivary Pipecolic Acid in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Braz. J. Oral Sci. 2022, 22, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SHahinas, J.; Hysi, D. Methods and Risk of Bias in Molecular Marker Prognosis Studies in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oral Dis. 2018, 24, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Pei, T.; Wu, G.; Liu, J.; Pan, W.; Pan, X. Circular RNAs as a Diagnostic Biomarker in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Meta-Analysis. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 80, 756–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furquim, C.P.; Soares, G.M.S.; Ribeiro, L.L.; Azcarate-Peril, M.A.; Butz, N.; Roach, J.; Moss, K.; Bonfim, C.; Torres-Pereira, C.C.; Teles, F.R.F. The Salivary Microbiome and Oral Cancer Risk: A Pilot Study in Fanconi Anemia. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susha, K.P.; Ravindran, R. Evaluation of Salivary Chemerin in Oral Leukoplakia, Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Healthy Controls. J. Orofac. Sci. 2023, 15, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Shi, H.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, C.; Shen, X. Association of Salivary miRNAs with Onset and Progression of Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders: Searching for Noninvasive Biomarkers. J. Dent. Sci. 2023, 18, 432–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peisker, A.; Raschke, G.F.; Fahmy, M.D.; Guentsch, A.; Roshanghias, K.; Hennings, J.; Schultze-Mosgau, S. Salivary MMP-9 in the Detection of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cirugia Bucal 2017, 22, e270–e275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamichi, E.; Sakakura, H.; Mii, S.; Yamamoto, N.; Hibi, H.; Asai, M.; Takahashi, M. Detection of Serum/Salivary Exosomal Alix in Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oral Dis. 2021, 27, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.H.; Sodnom-Ish, B.; Choi, S.W.; Jung, H.-I.; Cho, J.; Hwang, I.; Kim, S.M. Salivary Biomarkers in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Korean Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 46, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robledo-Sierra, J.; Ben-Amy, D.P.; Varoni, E.; Bavarian, R.; Simonsen, J.L.; Paster, B.J.; Wade, W.G.; Kerr, R.; Peterson, D.E.; Frandsen Lau, E. World Workshop on Oral Medicine VII: Targeting the Oral Microbiome Part 2: Current Knowledge on Malignant and Potentially Malignant Oral Disorders. Oral Dis. 2019, 25, 28–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Aziz Shaikh, S.; Denny, E.C.; Kumarchandra, R.; Natarajan, S.; Sunny, J.; Shenoy, N.; K P, N. Evaluation of Salivary Tumor Necrosis Factor α as a Diagnostic Biomarker in Oral Submucosal Fibrosis and Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Oral Cavity and Oropharynx: A Cross Sectional Observational Study. Front. Oral Health 2024, 5, 1375162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimal, J.; George, N.A.; Kumar, R.R.; Kattoor, J.; Kannan, S. Identification of Salivary Metabolic Biomarker Signatures for Oral Tongue Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Arch. Oral Biol. 2023, 155, 105780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, Q.-W.; Li, R.-F.; Zhong, N.-N.; Liu, B. Prognostic Value of CD8-to-EGFR Ratio in Salivary Microvesicles of Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oral Dis. 2023, 29, 1480–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.-F.; Huang, H.-D.; Fan, W.-L.; Jong, Y.-J.; Chen, M.-K.; Huang, C.-N.; Chuang, C.-Y.; Kuo, Y.-L.; Chung, W.-H.; Su, S.-C. Compositional and Functional Variations of Oral Microbiota Associated with the Mutational Changes in Oral Cancer. Oral Oncol. 2018, 77, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.F.; Lin, C.W.; Chuang, C.Y.; Lee, Y.C.; Chung, W.H.; Lai, H.C.; Chang, L.C.; Su, S.C. Host Genetic Associations with Salivary Microbiome in Oral Cancer. J. Dent. Res. 2022, 101, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantray, S.; Sharma, S.; Prabhat, K.; Nasrullah, N.; Gupta, M. Salivary Metabolite Signatures of Oral Cancer and Leukoplakia through Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. J. Oral Maxillofac. Pathol. 2022, 26, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulzar, R.A.; Ajitha, P.; Subbaiyan, H. Comparative Evaluation on the Levels of Salivary Mucin MUC1 in Precancerous and Cancerous Conditions. Int. J. Dent. Oral Sci. 2021, 8, 3734–3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Tripathi, A.; Patil, R.; Kumar, V.; Khanna, V.; Singh, V. Estimation of Salivary and Serum Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor in Treated and Untreated Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Oral Biol. Craniofacial Res. 2019, 9, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karmelić, I.; Salarić, I.; Baždarić, K.; Rožman, M.; Zajc, I.; Mravak-Stipetić, M.; Bago, I.; Brajdić, D.; Lovrić, J.; Macan, D. Salivary Scca1, Scca2 and Trop2 in Oral Cancer Patients— A Cross-Sectional Pilot Study. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, K.D.; Amenábar, J.M.; Schussel, J.L.; Torres-Pereira, C.C.; Bonfim, C.; Dimitrova, N.; Hartel, G.; Punyadeera, C. Profiling Salivary miRNA Expression Levels in Fanconi Anemia Patients—A Pilot Study. Odontology 2024, 112, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.; Bossuyt, P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.; Akl, E.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. MetaArXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Word No. | Group 1 (Red) | Occ | T.L.S. | Group 2 (Green) | Occ | T.L.S. | Group 3 (Blue) | Occ | T.L.S. | Group 4 (Yellow) | Occ | T.L.S. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bacterium | 9 | 36 | Early detection | 11 | 59 | Cell carcinoma | 6 | 37 | Early diagnosis | 9 | 54 |

| 2 | Carcinogenesis | 9 | 45 | Early stage | 5 | 23 | Concentration | 8 | 44 | Malignant transformation | 9 | 45 |

| 3 | Development | 9 | 40 | Marker | 16 | 70 | Evaluation | 13 | 70 | Potential biomarker | 8 | 35 |

| 4 | Disease | 20 | 75 | Risk | 7 | 31 | Healthy individual | 7 | 38 | Prognosis | 10 | 38 |

| 5 | Head | 12 | 48 | Salivary | 13 | 63 | Malignant disorder | 14 | 65 | Salivary metabolite | 5 | 23 |

| 6 | Important role | 5 | 25 | Sensitivity | 19 | 95 | Oral | 6 | 36 | |||

| 7 | Neck squamous cell carcinoma | 5 | 16 | Serum | 8 | 34 | OSCC group | 7 | 38 | |||

| 8 | Oral microbiome | 9 | 32 | Specificity | 18 | 89 | Reliable biomarker | 5 | 28 | |||

| 9 | Pathogenesis | 5 | 21 | Use | 8 | 35 | ||||||

| 10 | Progression | 10 | 46 | |||||||||

| 11 | Squamous cell carcinoma | 69 | 277 | |||||||||

| 12 | Tissue | 12 | 43 |

| Group (Color) | Main Authors | Citations/Document | TLS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (red) | Chaukar, Devendra; Joshi, Shriya; Vaidya, Milind; Dongre, Harsh; Iino, Mitsuyoshi | ≥50 | 75 |

| Group 2 (light blue) | Schierz, Eik; Blatt, Sebastian; Al-Nawas, Bilal | ≥50 | 70 |

| Group 3 (green) | Huang, Hsien-Da; Kuo, Yu-Lun; Tan, Yen-Jang | ≥50 | 85 |

| Group 4 (dark blue) | Kramer, Carolyn D.; Frias-Lopez, Jorge; Genco, Caroline A.; Choi, Yoonhee | ≥50 | 65 |

| Group 5 (yellow) | Johnson, N.W.; Al-Hebshi, N.M.; Chen, T. | ≥50 | 55 |

| Group 6 (purple) | Al-Hebshi, Nezar Noor; Chen, Tsute; Speicher, David J. | ≥50 | 70 |

| Group 7 (orange) | Chang, M.Y.; Wang, W.W.; Chang, K.W. | ≥50 | 55 |

| Group 8 (dark red) | Patankar, Sangeeta; Vijayaraghavan, Rajagopalan | ≥50 | 60 |

| Group 9 (light green) | Ghallab, Noha A. | ≥50 | 50 |

| Group 10 (pink) | Bandara, Herath Mudiyanselage | ≥50 | 45 |

| Author | Publication Year | Focus of the Investigation | Sample Size | Type of Study | Type of Analysis | Statistics | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lan, Qingying et al. [9] | 2023 | Microbiota, microflora, Mouth Neoplasms, carcinoma, and squamous cells | 18 OSCC patients, 21 OLK patients, and 21 healthy controls (HCs) | Case–control study | The researchers used metagenomic sequencing | Spearman’s correlation | The study found significant differences in the salivary microbiota among OSCC, OLK, and HCs |

| Daniel, Diana et al. [44] | 2021 | Biomarkers; oral squamous cell carcinoma; saliva; total sialic acid level | 60 subjects divided into three groups | Case–control study | The researchers analyzed total salivary sialic acid (TSA) levels using a sialic acid kit and UV spectrophotometer | Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney post hoc tests | The study suggested that salivary sialic acid could be a reliable biomarker for detecting OSCC and OPMDs |

| Yap, T. et al. [45] | 2019 | Genetics, periodontitis, gingivitis, biomarkers, carcinoma, microRNAs | 190 individuals | Systematic review | Developed dysregulation score (dSCORE) and risk classification algorithm | qPCR analysis, dSCORE and risk classification algorithm, sensitivity and specificity analysis, demographic and risk factor analysis | MicroRNA for analysis can be predictably isolated from oral swirls sourced from individuals with a range of demographic, systemic, and oral health findings |

| Zheng, Jun et al. [46] | 2018 | Mouth Neoplasms, carcinoma, mouth squamous cell carcinoma, saliva level, early detection of cancer | 202 individuals | Observational clinical study | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays | Student’s t-test, ANOVA, Pearson’s correlation, Spearman’s correlation, ROC analysis | Salivary and serum levels of Naa10p and CEA in OSCC patients were significantly higher than those detected in OPML and the control groups, although patients with OPMLs also showed increased salivary and serum Naa10p and CEA levels as compared to the control group |

| Hes, Cecilia et al. [47] | 2024 | Microbiome, Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Head and Neck, metagenomics, DNA library | 52 patients | Prospective study | Shotgun metagenomic sequencing | Wilcoxon rank-sum test, Kruskal–Wallis test, Kaplan–Meier survival analysis, Cox proportional hazards model, PERMANOVA, Spearman’s correlation | All patients developed CRT-induced mucositis, including 42% with severe events (i.e., CTCAE v5.0 grade ≥ 3) and 25% who required enteral feeding |

| Mehdipour, Masoumeh et al. [48] | 2023 | Biomarkers, squamous cells, microRNA | 60 patients divided into four groups | Case–control study | Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) | Kruskal–Wallis and Dunn–Bonferroni tests | Altered expressions of microRNA-146a and microRNA-155 in dysplastic OLP and OSCC could serve as potential biomarkers for malignancy |

| Rapado-González, Óscar et al. [49] | 2022 | Biomarkers, carcinoma, squamous cells, tumor, Cell-Free Nucleic Acids | 34 subjects divided into two groups | Preliminary study | The researchers analyzed the concentration and integrity of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) fragments in saliva samples using molecular techniques | Descriptive Statistics | The study found significant differences in the integrity and quantity of cfDNA between OSCC patients and healthy controls |

| Menaka, T.R. et al. [50] | 2019 | Biomarkers; saliva; salivary alkaline phosphatase | 42 individuals | Observational cross-sectional study | Kinetic photometric method | Mann–Whitney U test | Data obtained were subjected to statistical analysis; the mean S-ALP was 18.00 IU/L for normal individuals without tobacco usage, 4.60 IU/L for smokers without lesions, 7.50 IU/L for tobacco chewers without any lesions, and 64.90 IU/L for individuals with OPMD |

| Sridharan, Gokul et al. [51] | 2019 | Biomarkers, squamous cells, metabolome | 61 patients | Observational case–control study | Q-TOF–liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry | MassHunter profile software and Metlin database, ANOVA | Significant upregulation of 1-methylhistidine, inositol 1,3,4-triphosphate, d-glycerate-2-phosphate, 4-nitroquinoline-1-oxide, 2-oxoarginine, norcocaine nitroxide, sphinganine-1-phosphate, and pseudouridine in oral leukoplakia and OSCC was noted |

| Bandara, Herath Mudiyansalage Herath Nihal et al. [52] | 2019 | Microbiology, saliva, mouth flora, mycobiome, salivation, biodiversity | 20 referenced studies | Systematic review | Literature review, NGS, bioinformatics analysis | Descriptive statistics, ANOVA | Identified Candida as dominant genus; linked fungal diversity to oral diseases like OSCC and periodontitis |

| Tavakoli, Fatemeh et al. [11] | 2024 | Mouth squamous cell carcinoma, biological marker, mouth cancer, diagnosis | 40 patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) | Observational study | Independent sample t-test or its nonparametric equivalent, Mann–Whitney U test | SPSS 17 statistical software | The results showed a statistically significant difference in the mean levels of salivary transferrin between the OSCC patients and the healthy controls |

| Palaia, Gaspare et al. [53] | 2022 | miRNAs, OSCC, liquid biopsy | 34 studies | Literature search | Qualitative and quantitative review, subgroup analysis | Descriptive statistics, SIGN checklist for bias | The analysis showed that 57 microRNAs of liquid biopsy samples of four different fluids (whole blood, serum, plasma, and saliva) were analyzed |

| Afifi, Salsabeel et al. [54] | 2021 | Diagnostic accuracy study, oral cancer, potentially malignant lesions, saliva | 28 participants divided into three groups | Prospective pilot study | The researchers used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) | Chi-square test | Indicated its potential as a promising biomarker for the early detection of oral malignancy |

| Garg, Ruchika et al. [55] | 2017 | Oral cancer, oral leukoplakia, oral lichen planus, potentially malignant conditions, survivin | 96 subjects | Comparative study | The researchers used high-throughput sequencing and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) | Mann–Whitney U test | The study found statistically significant differences in the levels of salivary survivin among the groups |

| Perera, M. et al. [56] | 2018 | 16S, microbiota, ribosomal, RNA, dysbiosis, Sequence Analysis, squamous cells, DNA | The study included 25 cases of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) and 27 controls with fibroepithelial polyps (FEPs) | Case–control study | The researchers used high-throughput sequencing | Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe), PICRUSt | The study found that OSCC tissues had lower species richness and diversity compared to FEP tissues |

| Farshbaf, Alieh et al. [57] | 2024 | Metabolism, Mouth Neoplasms, biomarkers, squamous cells, biological marker, microRNAs | 30 healthy control individuals, 30 patients with erosive/atrophic oral lichen planus (OLP), and 31 patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC); this is a cross-sectional study | The researchers used quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) | Shapiro–Wilk test, Kruskal–Wallis test, Pearson’s chi-square test, Mann–Whitney U test | The study found a statistically significant difference in miR-3928 expression between the three groups (p < 0.05) | |

| Nosratzehi, Tahereh et al. [58] | 2017 | Biomarkers, carcinoma, tumor | 75 cases | Observational study | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and optical density | SPSS version 20 and one-way ANOVA and LSD tests were used to analyze the data | The mean salivary endothelin-1 level in patients with OSCC was 163.98 pg/mL; in patients with OLP, it was 160.9 pg/mL; and in healthy people, it was 137.19 pg/ml |

| Vesty, Anna et al. [59] | 2018 | Cytokines, head and neck cancer, oral microbiome, oral mycobiome, saliva | 30 participants | Observational study | The researchers used 16S rRNA gene sequencing for bacterial analysis and ITS1 amplicon sequencing for fungal analysis | Diversity-based analyses | The study found that the bacterial communities of HNSCC patients were significantly different from those of healthy controls but not from dentally compromised individuals |

| Blatt, Sebastian et al. [60] | 2017 | Biomarkers, carcinoma, squamous cells, tumor, cell cycle regulation, Drug Resistance, prognosis | 128 studies | Systematic review | Literature analysis, systematic review methodology, narrative synthesis | Not applicable | In the review, the current evidence on over 100 different biomarkers found for predicting prognosis, outcome, and therapy alterations of OSCC is summarized |

| Saleem, Zohra et al. [61] | 2021 | Head and Neck Neoplasms, squamous cells, Matrix Metalloproteinase | 91 subjects | Analytical study | The researchers used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) | One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) | The study found a significant difference in salivary MMP-12 expression between the groups (p < 0.001) |

| Tarrad, Nayroz Abdel Fattah et al. [62] | 2023 | Biomarkers, Head and Neck Neoplasms, squamous cells, microRNA, precancerous conditions | 36 participants | Observational diagnostic study | The researchers used quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) | Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis | The study found that OSCC showed the highest fold change for LINC00657 and the lowest fold change for miRNA-106a among the included groups |

| Cohen, Erin R. et al. [63] | 2020 | Saliva, metabolism, biomarkers, progression-free survival, prognosis | 64 cases | Prospective study | Immunohistochemistry, salivary biomarker analysis, multivariate analysis | Multivariate analysis, p-values for associations | High solCD44 levels associated with strong CD44 tissue expression |

| Rajaram, Suganya et al. [64] | 2017 | Biomarkers, carcinoma, N-acetylneuraminic acid, saliva, serum | 31 patients | Case–control study | Colorimeter, acidic ninhydrin method | Student’s t-test | There is elevated serum and salivary sialic acid level in moderately/poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma without any significant change in well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma |

| Kitamura, Naoya et al. [65] | 2023 | Head and Neck Neoplasms, squamous cells, DNA | 115 Japanese patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) | Case–control study | The researchers used quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) | Chi-square test | The study found that 20.9% of the patients were positive for MCPyV DNA |

| Gaba, Fariah I. et al. [66] | 2021 | Biomarkers, carcinoma, Head and Neck Neoplasms, sensitivity and specificity, interleukin 8, diagnostic accuracy | 17 articles | Meta-analysis | Sensitivity and specificity analysis | Specificities of biomarkers | Specificities of the biomarkers analyzed were found to be IL-8 (0.69; 95%CI 0.66–0.99), IL1-β (0.47; 95%CI 0.46–0.90), DUSP-1 (0.75; 95%CI 0.33–1), and S100P (0.73; 95%CI 0.18–0.99) |

| Cheng, Y.-S.L. et al. [67] | 2017 | Metabolism, biomarkers, carcinoma, reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction | 105 human subjects | Observational study | Bio-Rad CFX96 Real-Time System | Mann–Whitney U test with Bonferroni corrections | Only S100P showed significantly higher levels in patients with OSCC compared to both patients with CPNS (p = 0.003) and CPS (p = 0.007) |

| Shabbir, Alveena et al. [68] | 2022 | Mouth Neoplasms, biomarkers, carcinoma | 80 participants | Analytical study | The researchers used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) | One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) | The study found that salivary Cathepsin B levels were significantly increased in patients with OSCC compared to healthy controls (p < 0.001) |

| Mougeot, Jean-Luc C. et al. [69] | 2019 | Streptococcus mutans, bacterial microbiome, cancer radiotherapy, DMFS index, host–bacterium interaction, microbial diversity | 31 head and neck cancer (HNC) patients | Longitudinal study | The researchers used high-throughput sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene | Beta-diversity analysis and DMFSs (Decayed, Missing, and Filled Surfaces) scores | The study found significant changes in the oral microbiome at T6 and T18 |

| Ishikawa, Shigeo et al. [70] | 2019 | Biomarkers, tumor marker, Hyperplasia | 48 participants | Case–control study | The researchers used capillary electrophoresis–mass spectrometry (CE-MS) | Multiple logistic regression (MLR) | The study identified six metabolites that were significantly different between OSCC/OED and PSOML |

| Babiuch, Karolina et al. [71] | 2019 | Antioxidants, Oxidative Stress, Mouth Neoplasms, biomarkers, squamous cells | 60 patients | Prospective study | Salivary biomarkers | Chi-square test; Dunn’s post hoc test; Kruskal–Wallis test; Spearman’s correlation test; Mann–Whitney test | The activity of SOD was significantly higher in the OSCC group in comparison with the OL and control groups |

| Shan, Jing et al. [72] | 2019 | Saliva analysis, biomarkers, diagnostic test accuracy study, proteomics, early detection of cancer, interleukin 1 receptor blocking agent | 60 saliva samples | Diagnostic test accuracy study | Isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ) method | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) | In total, 246 differentially expressed proteins were identified by comparing each two groups, and 21 proteins were differentially expressed when OSCC was compared with both OPMD and control |

| Katase, Naoki et al. [73] | 2023 | Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Head and Neck, Cell Line, Western blotting, cell proliferation, Intercellular Signaling Peptides and Proteins, prognosis | 60 patients | Case–control study | The researchers used immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Chi-square test and logistic regression analysis | The study found that high expression levels of DKK3 and CKAP4 were significantly associated with advanced stage and poorer prognosis in oral cancer patients |

| Abdelwhab, Amira et al. [74] | 2023 | Metabolism, Mouth Neoplasms, biomarkers, Head and Neck Neoplasms, histology, dysplasia | Forty oral potentially malignant disorders | Experimental study | Real-time PCR | Comparison between groups | Mucin1 expression in saliva was significantly elevated in oral potentially malignant disorders when compared with controls |

| Kallalli, Basavaraj N. et al. [75] | 2016 | Histopathology, mouth disease, saliva level | 60 subjects | Observational study | ERBA-CHEM 5 semi-auto-analyzer | Descriptive statistics and paired t-test using the SPSS software | The mean LDH levels were as follows: Group I, 608.28 ± 30.22; Group II, 630.96 ± 39.80; and Group III, 182.21 ± 34.85 |

| Chapple, Iain L C et al. [76] | 2018 | Periodontitis, gingivitis, peri-implantitis | 26 experts | Consensus report | The report involved a comprehensive review | Qualitative analysis and expert consensus rather than quantitative statistical methods | The report introduced a new classification system for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions, emphasizing a more comprehensive approach that includes stages and grades of periodontitis, as well as conditions affecting peri-implant health |

| Jolivet-Gougeon, Anne et al. [77] | 2021 | Microbiota, RNA 16S, dental caries, microbial diversity, immunocompromised patient, prevalence | 42 papers | Scoping review | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Protocols (PRISMA—ScR) | A data-charting form was used | They showed a link between the abundance of Capnocytophaga spp. in the oral microbiota and various local pathologies (higher for gingivitis and halitosis; lower in active smokers, etc.) or systemic diseases (higher for cancer and carcinomas, IgA nephropathy, etc.) |

| Ishikawa, Shigeo et al. [78] | 2020 | Saliva analysis, cancer diagnosis, squamous cell carcinoma | 60 patients | Case–control study | Salivary biomarker analysis | Multiple logistic regression (MLR); Mann–Whitney U test | Saliva analysis showed significant differentiation between SCC patients and control groups |

| Banavar, Guruduth et al. [79] | 2023 | RNA, saliva analysis, biomarkers, cancer staging, genomic RNA, head and neck tumor, sensitivity and specificity | 1.175 individuals | Observational study | Machine learning analysis | Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) | The classifier showed a specificity of 94% and sensitivity of 90% for participants with oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) and 84.2% for participants with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) |

| Hashimoto, Kengo et al. [42] | 2022 | Saliva analysis, microbial diversity, Bacteroidetes, high-throughput sequencing, cancer recurrence | 86 participants | Observational study | The researchers used next-generation sequencing (NGS) | Fisher’s exact test, chi-square test, logistic regression analysis | The study found significant differences in the abundances of certain bacterial genera and phyla among the groups |

| Zhong, Xiaohuan et al. [80] | 2021 | RNA 16S, Mouth Neoplasms, microbial community, community dynamics, oral submucous fibrosis | 162 participants | Cross-sectional study | 16S rRNA gene sequencing | PERMANOVA; Wilcoxon rank-sum; Kruskal–Wallis | The study found that the oral microbiome of people who chew areca nuts is different from that of people who do not chew areca nuts |

| Khalil, Marwa et al. [81] | 2019 | Leukoplakia; oral squamous cell carcinoma; saliva; zinc | 45 patients | Randomized clinical trial | Standard spectrophotometric methods | ANOVA and chi-square test | There was a highly significant decrease in the level of salivary Zn in patients with OSCC when compared to OL patients and controls (p < 0.05) |

| Chari, Abinaya et al. [82] | 2016 | Biomarkers, squamous cells, Surveys and Questionnaires, blood | 35 patients | Case–control study | Blood biomarker analysis | Two-tailed t-test and chi-square analysis | The mean serum LDH value for patients with smokeless tobacco-related oral lesions was 446.8 U/L, compared to 269.4 U/L for healthy controls |

| Chen, Jijun et al. [43] | 2023 | RNA, real-time polymerase chain reaction, biomarkers, Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Head and Neck, cell migration, blood, protein expression | 132 participants | Case–control study | Real-time PCR analysis | ANOVA, Tukey test | The study found that miR-19a, GPR39 mRNA, and PKC mRNA were upregulated while GRK6 mRNA was downregulated in the serum and saliva samples of OSCC patients compared to healthy controls |

| Sayal, Lana et al. [83] | 2023 | Saliva analysis, biomarkers, Head and Neck Neoplasms, sex difference, early cancer diagnosis, liquid biopsy | 133 leukoplakia patients versus 137 healthy volunteers | Observational study | Salivary cf-mtDNA and cfDNA were quantified using Multiplex Quantitative PCR | Chi-square test; Shapiro–Wilk test of normality; nonparametric tests (Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal–Wallis H test) | The study found that the median scores of cfDNA and cf-mtDNA were significantly higher among HNSCC patients compared to healthy controls and OLK patients |

| Yuanbo, Zhan et al. [16] | 2024 | DNA, Papillomavirus Infections, tongue tumor | 60 patients | Pilot study | The researchers used 16S rRNA gene sequencing | Wilcoxon test; multiple comparisons using FDR p-value correction; Spearman’s rank test | The study found that microbiota diversity was significantly increased in p16-positive patients compared to p16-negative patients |

| Rani, N. Alice Josephine et al. [10] | 2023 | ELISA; interleukin 6; oral potentially malignant disorders | 60 patients | Cross-sectional comparative study | Saliva samples; ELISA | Shapiro–Wilk test; one-way ANOVA; post hoc Tukey test; Kruskal–Wallis test | The study found that the concentration of IL-6 was significantly higher in the OSCC group compared to the other three groups |

| Ameena, M. et al. [84] | 2019 | ELISA; leukoplakia; oral squamous cell carcinoma | 90 participants | Comparative study | ELISA test | Statistical analysis was performed using the one-way ANOVA | The study found that salivary TNF-α levels were significantly elevated in patients with OSCC compared to those with leukoplakia and healthy controls |

| Yost, Susan et al. [85] | 2018 | Microbiota, squamous cells, transcriptome, Virulence, Metagenome | Small pilot study with a limited number of participants | Pilot study | Metatranscriptome analysis | LEfSe; Kruskal–Wallis (KW) sum-rank test; Wilcoxon test | The study found that Fusobacteria exhibited a statistically significant increase in transcript abundance at tumor sites and tumor-adjacent sites in cancer patients compared to healthy controls |

| Rapado-González, Óscar et al. [34] | 2024 | Biomarkers, cancer diagnosis, gene expression, genomic DNA | Study included six consecutive patients | Cross-sectional study | Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling | Principal component analysis (PCA) and ROC curve analysis were assessed to obtain the best models | The study identified a group of novel tumor-specific DNA methylation markers with diagnostic potential in saliva |

| Feng, Yun et al. [86] | 2019 | Saliva, metabolism, biomarkers, squamous cells | 16 patients | Observational study | The researchers used human protease array kits, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), Western blot, and immunofluorescence | One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) | The study found that the salivary protease spectrum was significantly associated with oral diseases |

| Ghallab, Noha A. et al. [87] | 2017 | Saliva, metabolism, biomarkers, Intercellular Signaling Peptides and Proteins | 45 individuals | Case–control study | The researchers used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) | The study employed receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve analysis | The study found that serum and salivary levels of chemerin and MMP-9 were significantly higher in patients with OSCC compared to those with OPMLs and healthy controls |

| Sawant, Sharada et al. [88] | 2016 | Biomarkers, squamous cells, prognosis, CD44 protein, survival rate | 87 patients | Prospective study | The researchers performed immunohistochemistry | Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test | The study found significant correlations between the expression of Oct4, CD44, and c-Myc with overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) independently |

| Lee, L.T. et al. [89] | 2018 | Mouth tumor, biomarkers, carcinoma, cytokine, blood sampling, interleukin 1 beta, interleukin 6, risk factors | 65 patients | Case–control study | Luminex Bead-based Multiplex Assay | Mann–Whitney U test and Kruskal–Wallis test | The study found that plasma levels of IP-10 in early-stage OSCC patients differed significantly from those in controls |

| Triani, Maulina et al. [90] | 2021 | Betel nut; Ki-67; micronucleus; oral squamous cell carcinoma; saliva | 60 participants | Cross-sectional analytic survey | Papanicolaou method | Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis tests | The study found significant differences in Ki-67 expression and micronucleus counts between the betel nut chewers with OSCC and the control groups |

| Perera, Manosha et al. [91] | 2017 | Mycobiome, carcinoma, DNA ribosomal spacer, microbiome, squamous cells | 52 tissue biopsies | Observational study | The researchers used Illumina sequencing and BLASTN algorithm | Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) | The study found that the mycobiome in OSCC was dominated by Candida albicans, with significantly lower species richness and diversity compared to FEPs |

| Chan, Jason Y.K. et al. [92] | 2022 | Ribosomal, RNA 16S, dysbiosis, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, genotyping | 166 Chinese adults | Cohort study | Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) | Mann–Whitney; Wilcoxon rank-sum test | The study found that 15.7% of the HNSCC patients were positive for HPV DNA, with infection rates varying by cancer subtype |

| Kaur, Jasdeep et al. [93] | 2016 | Biomarkers, sensitivity and specificity, risk factor, biopsy | 200 participants | Observational study | Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis | Mann–Whitney U test | The findings revealed that patients with OSCC and precancerous conditions exhibited significantly higher salivary levels of 8-OHdG and MDA, alongside lower levels of vitamins C and E, compared to healthy controls |

| Zhu, Weiwen et al. [36] | 2024 | Squamous cells, Streptococcus, Capnocytophaga gingivalis, Cell Line, Fluorescence, In Situ Hybridization | 178 participants | Comparative observational study | 16S rRNA gene sequencing | PERMANOVA, t-test, ANOVA, regression | The findings revealed that the overall microbiome diversity was higher in healthy controls compared to OSCC patients |

| Chen, M.Y. et al. [39] | 2021 | Microbiota, Head and Neck Neoplasms, artificial intelligence | OSF (n = 18) and OSCC-OSF (n = 34) groups | Comparative observational study | 16S rRNA gene sequencing | ANOVA, regression, Alpha-diversity indices | The study found significant differences in the salivary microbiomes between the OSCC-OSF and OSF groups |

| Kumaran, Jimsha et al. [94] | 2022 | MicroRNA; non-invasive method; potential biomarker | Does not specify the exact number | Observational study | Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) | Not applicable | Discusses the differential expression of specific salivary miRNAs and their potential roles as biomarkers for oral diseases |

| Suresh, H. et al. [95] | 2022 | Alpha-L-fucosidase; oral squamous cell carcinoma; oral submucous fibrosis; salivary biomarker | 40 participants | Comparative study | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) | Pearson’s correlation | The study found a significant increase in AFU levels in both saliva and serum of OSMF patients compared to healthy controls |

| Ferrazzo, Kívia Linhares et al. [96] | 2022 | Saliva; biomarkers; squamous cells | 20 participants | Case–control study | Questionnaire; saliva samples; liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) | Shapiro–Wilk test; Student’s t-test; Mann–Whitney test | The results suggest that while salivary pipecolic acid demonstrates high sensitivity, its specificity is moderate, indicating potential as a non-invasive biomarker for HNSCC detection |

| SHahinas, J. et al. [97] | 2018 | Metabolism, biomarkers, carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, prognosis, immunohistochemistry | 36 articles | Systematic review | Quality in Prognosis Studies (QUIPS), data extraction form | Cox regression and Kaplan–Meier | The findings indicated that the majority of the reviewed studies were replication prognostic factor studies (35 out of 36) |

| Huang, Long et al. [98] | 2022 | Biomarkers, carcinoma, diagnostic test accuracy study, diagnostic value | Six studies | Meta-analysis | Hierarchical analysis | Quality Assessment for Studies of Diagnostic Accuracy 2 | The pooled sensitivity and specificity of circRNAs for OSCC diagnosis were 0.72 and 0.81, respectively |

| Furquim, C.P. et al. [99] | 2017 | Microbiota, saliva, squamous cells, risk factors, Gingival Hemorrhage | 61 patients | Cross-sectional | 16S rRNA gene sequencing | General linear models | The analysis revealed that the most abundant bacterial phyla in the salivary microbiome of FA patients were Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes |

| Susha, Karthika Pradeep et al. [100] | 2023 | Salivary biomarker, oral squamous cell carcinoma, oral leukoplakia, early diagnosis | 90 patients | Case–control study | Salivary chemerin; ELISA | Independent t-test; analysis of variance test (F test); Scheffe’s multiple comparisons (post hoc test) | The study found that salivary chemerin levels were significantly higher in the OSCC group compared to both the OL and HC groups |

| Liu, Wei et al. [101] | 2023 | Bubble analysis; non-invasive diagnosis; oral cancer; oral potentially malignant disorders; saliva; microRNAs | 17 eligible studies | Systematic review | Bubble chart analysis | Excel Visual Basic for Applications | The analysis identified that miR-21 exhibited the highest diagnostic power for detecting the onset of OPMDs, followed by miR-31 and miR-142 |

| Peisker, Andre et al. [102] | 2017 | Biomarkers, carcinoma, biopsy, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay | 60 participants | Case–control study | Saliva samples; enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) | Mann–Whitney U test | The median absorbance MMP-9 value for the OSCC group was 0.186 (IQR = 0.158), while the control group had a median value of 0.156 (IQR = 0.102) |

| Nakamichi, Eiji et al. [103] | 2021 | Saliva, biomarkers, carcinoma, Western blotting, immunoreactivity, protein analysis | 57 patients | Case–control study | Serum/salivary exoAlix levels | Chi-square tests; Mann–Whitney U tests; Kruskal–Wallis test; Dunn’s tests; Fisher’s exact tests; Spearman’s correlation coefficient by rank; Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank tests | The findings revealed that both serum and salivary exoAlix levels were significantly higher in OSCC patients compared to healthy controls |

| Nguyen, Truc Thi Hoang et al. [104] | 2020 | Carcinogenesis, saliva protein, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, liquid biopsy | This study did not involve a specific sample size | Narrative review | Literature review | Not applicable | The review highlights several salivary biomarkers with potential diagnostic and prognostic value for OSCC |

| Robledo-Sierra, Jairo et al. [105] | 2019 | Microbiota, carcinoma, squamous cells, bacterium identification | 23 studies on oral squamous cell carcinoma, 2 studies on oral leukoplakia, and 4 studies on oral lichen planus | Systematic review | The researchers performed a comprehensive literature review and meta-analysis | The study employed qualitative synthesis and quantitative analysis | The study found substantial differences in diagnostic criteria, sample types, regions sequenced, and sequencing methods across the included studies |

| Abdul Aziz Shaikh, Sabiha et al. [106] | 2024 | TNF-α, oral submucosal fibrosis, squamous cell carcinoma, salivary biomarkers, chronic inflammation | 45 participants | Case–control study | Saliva samples; salivary TNF-α levels; ELISA kit | ANOVA and post hoc Tukey HSD | The analysis revealed no significant differences in salivary TNF-α levels among the OSMF, SCC, and control groups |

| Vimal, Joseph et al. [107] | 2023 | Biomarkers, Head and Neck Neoplasms, Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Head and Neck | 20 samples from patients | Case–control study | Untargeted metabolomics | Progenesis QI | The study identified N-Acetyl-D-glucosamine, L-Pipecolic acid, and L-Carnitine as signature diagnostic biomarkers for oral tongue squamous cell carcinoma |

| Man, Qi-Wen et al. [108] | 2023 | Mouth Neoplasms, biomarkers, flow cytometry, protein expression, prognosis | 61 patients with OSCC, 21 healthy patients | Short communication | Salivary mRNA | Mann–Whitney test, univariate and multivariate analyses | Identified potential of salivary mRNA biomarkers for OSCC early prediction |

| Yang, Shun-Fa et al. [109] | 2018 | Genomics, microbiota, microbial community, histopathology | 103 participants | Observational study | 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing | Taxonomic analysis | The analysis revealed three distinct MSC groups in OSCC patients, each significantly associated with specific demographic and clinical features |

| Yang, S.F. et al. [110] | 2022 | Microbiota, RNA, mouth tumor, Head and Neck Neoplasms, squamous cells | 315 participants | Meta-analysis | Sequencing the salivary microbiome | Quantitative trait loci (QTL) | The study identified associations of three genetic loci with the abundance of specific bacterial genera and four loci with measures of β diversity |

| Tantray, Shoborose et al. [111] | 2022 | Metabolite, OSCC, OLK | 90 participants | Comparative observational study | The researchers employed gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) | Principal component analysis (PCA) | Fifteen metabolites showed significant differences between the control, OLK, and OSCC groups |

| Gulzar, Rukhsaar Akbar et al. [112] | 2021 | Salivary MUC1, cancerous conditions | 30 patients | Comparative observational study | ELISA | ANOVA | MUC1 levels were highest in OSCC (19.33 ± 4.39 ng/mL), followed by premalignant (8.32 ± 3.08 ng/mL) and control (2.73 ± 0.34 ng/mL) |

| Gupta, Archana et al. [113] | 2019 | Mustard oil, dry socket, Curcumin, Holy powder, anti-inflammatory | 178 patients | Randomized clinical trial | Comparative analysis of treatment outcomes between two groups | Chi-square test | Group A (turmeric and mustard oil) showed faster symptom relief (starting by day 2) compared to Group B (zinc oxide eugenol, relief by day 4) |

| Ahmed, Ahmed A. et al. [33] | 2024 | Saliva, Mouth Neoplasms, DNA sequencing, biomarkers, circulating free DNA, liquid biopsy | 250 participants | Observational study | Descriptive and inferential statistics | Nuclear morphometric analysis (NMA) using Image J, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis | Significant differences in nuclear morphometric parameters (NMPs) among different smoking groups |

| Karmelić, Ivana et al. [114] | 2022 | Oral cancer; early diagnosis; biomarkers; saliva | 58 patients | Cross section | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing | Mann–Whitney U test and Kolmogorov–Smirnov test | Difference between the OSCC group and the control group was found between the levels of SCCA1 and SCCA 2 both in UWS and SWS |

| Tang, Kai Dun et al. [115] | 2024 | Metabolism, biomarkers, Head and Neck Neoplasms, microRNA | 66 participants | Pilot study | Quantitative analysis using qPCR (quantitative polymerase chain reaction) | t-tests; one-way ANOVA; Tukey–Kramer HSD multiple comparison; Pearson’s correlation | The study identified specific miRNAs (miR-744, miR-150-5P, and miR-146B-5P) with high discriminatory capacity between Fanconi anemia patients and healthy controls |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dumitrescu, R.; Bolchis, V.; Fratila, A.D.; Jumanca, D.; Buzatu, B.L.R.; Sava-Rosianu, R.; Alexa, V.T.; Galuscan, A.; Balean, O. The Global Trends and Advances in Oral Microbiome Research on Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13020373

Dumitrescu R, Bolchis V, Fratila AD, Jumanca D, Buzatu BLR, Sava-Rosianu R, Alexa VT, Galuscan A, Balean O. The Global Trends and Advances in Oral Microbiome Research on Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(2):373. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13020373

Chicago/Turabian StyleDumitrescu, Ramona, Vanessa Bolchis, Aurora Doris Fratila, Daniela Jumanca, Berivan Laura Rebeca Buzatu, Ruxandra Sava-Rosianu, Vlad Tiberiu Alexa, Atena Galuscan, and Octavia Balean. 2025. "The Global Trends and Advances in Oral Microbiome Research on Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review" Microorganisms 13, no. 2: 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13020373

APA StyleDumitrescu, R., Bolchis, V., Fratila, A. D., Jumanca, D., Buzatu, B. L. R., Sava-Rosianu, R., Alexa, V. T., Galuscan, A., & Balean, O. (2025). The Global Trends and Advances in Oral Microbiome Research on Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. Microorganisms, 13(2), 373. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13020373