Glucose-Lowering Effects and Safety of Bifidobacterium longum CKD1 in Diabetic Dogs and Cats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Animals and Ethical Approval

2.2. Administration of B. longum CKD1 and Measurement of Glycemic Parameters

2.3. Gut Microbiota Analysis

2.4. Assessment of Hematological and Biochemical Parameters for Safety Monitoring

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

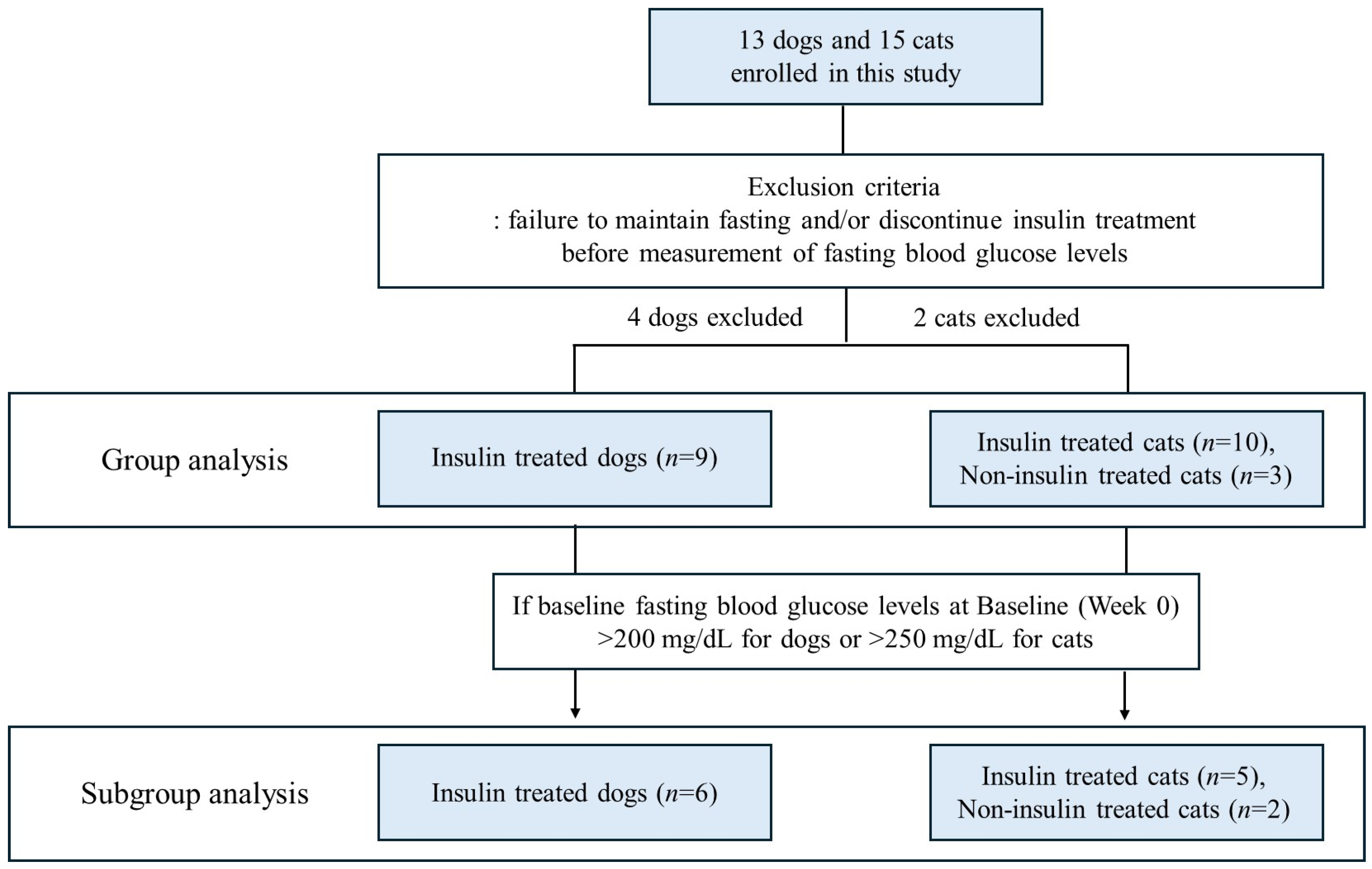

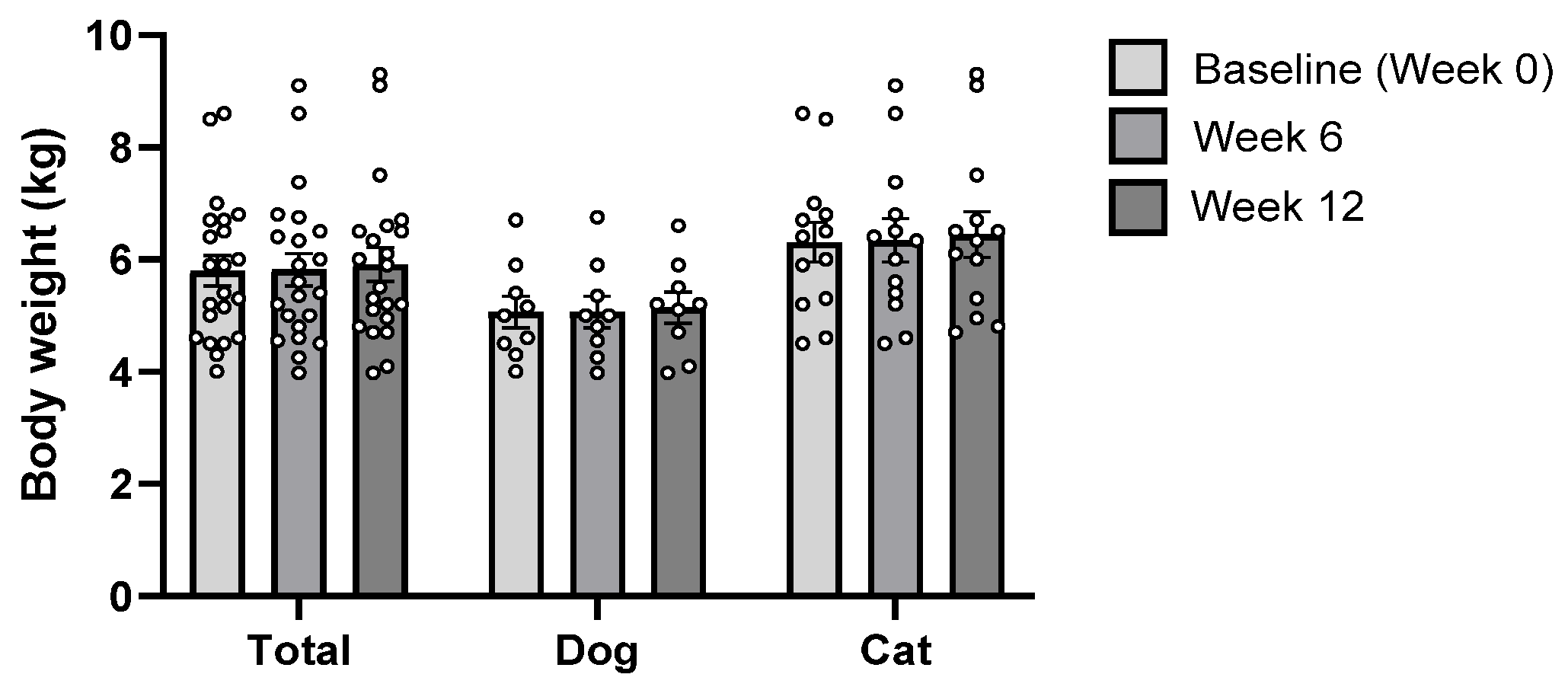

3.1. Characteristics of Study Population

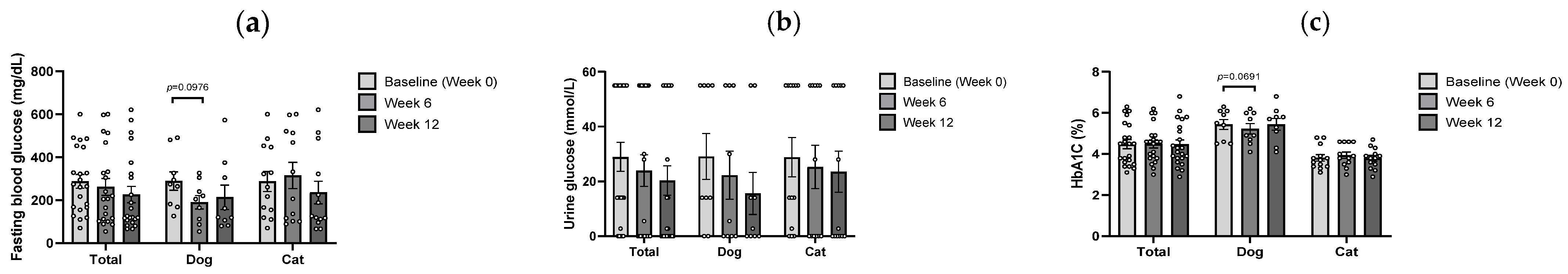

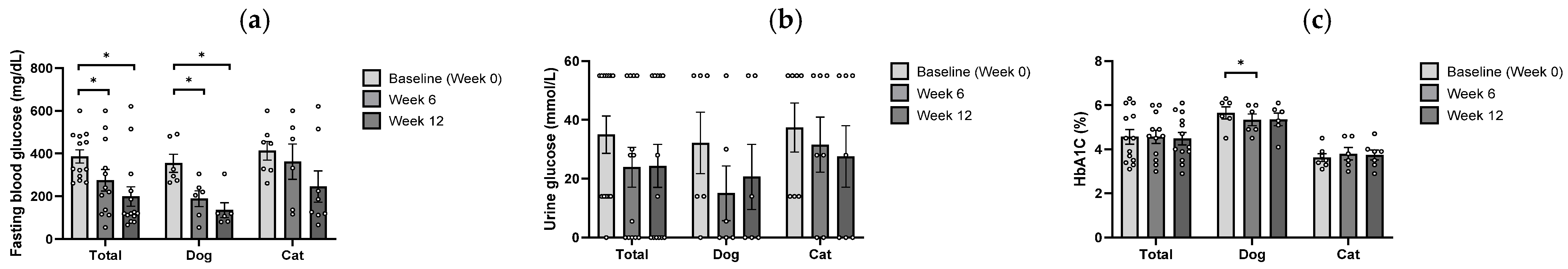

3.2. Glycemic Response to B. longum CKD1

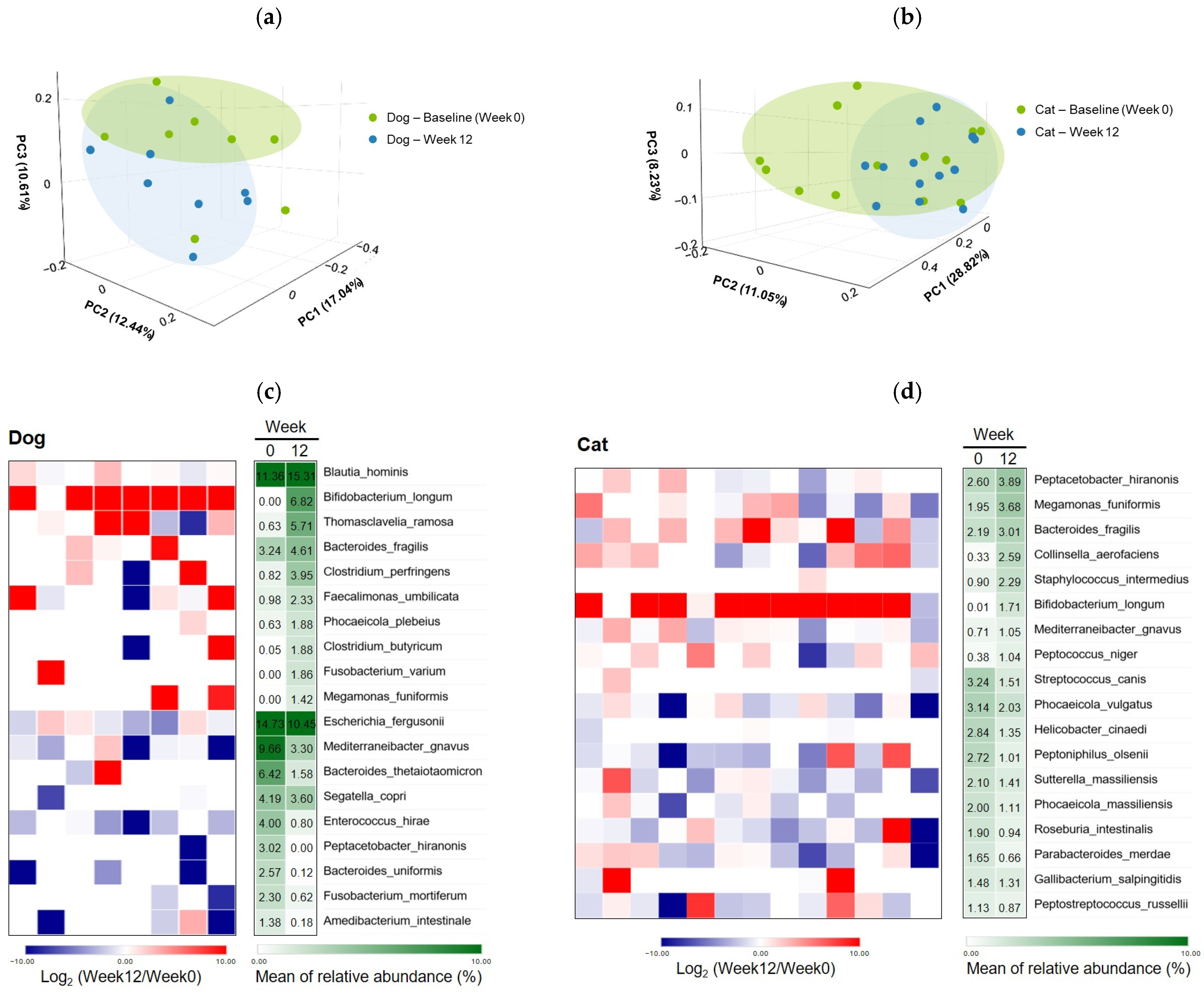

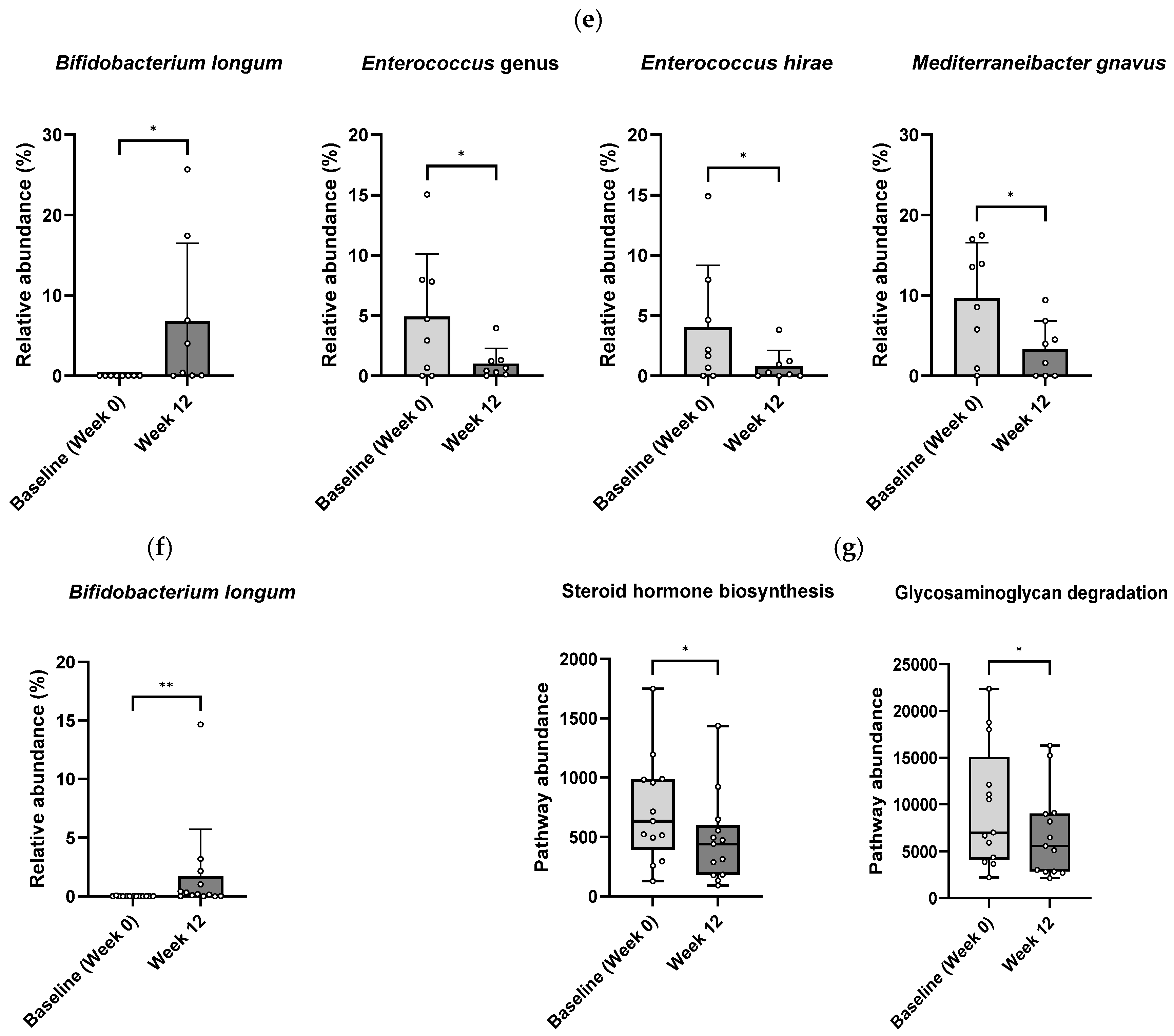

3.3. Gut Microbiota Modulation by B. longum CKD1

3.4. Safety of B. longum CKD1

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALT | alanine aminotransferase |

| ALB | albumin |

| ALP | alkaline phosphatase |

| ASV | amplicon sequence variant |

| B. longum | Bifidobacterium longum |

| BLAST | Basic Local Alignment Search Tool |

| BUN | blood urea nitrogen |

| CBC | complete blood count |

| CFU | colony-forming units |

| CGM | continuous glucose monitoring |

| CRE | creatinine |

| DM | diabetes mellitus |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| GLOB | globulin |

| GGT | γ-glutamyl transferase |

| HCT | hematocrit |

| Hb | hemoglobin |

| HbA1c | glycated hemoglobin |

| IACUC | Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee |

| IP | inorganic phosphorus |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| KO | KEGG Orthology |

| LBPs | live biotherapeutic products |

| NCBI | National Center for Biotechnology Information |

| PLT | platelet |

| PCoA | principal coordinate analysis |

| QIIME | Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology |

| RBC | red blood cell |

| SCFAs | short-chain fatty acids |

| SGLT2 | sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 |

| TBIL | total bilirubin |

| TC | total cholesterol |

| TP | total protein |

| WBC | white blood cell |

| 16S rRNA | 16S ribosomal RNA |

References

- Behrend, E.; Holford, A.; Lathan, P.; Rucinsky, R.; Schulman, R. 2018 AAHA Diabetes Management Guidelines for Dogs and Cats. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2018, 54, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoenig, M. The Cat as a Model for Human Obesity and Diabetes. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2012, 6, 525–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, R.W.; Reusch, C.E. Animal Models of Disease: Classification and Etiology of Diabetes in Dogs and Cats. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 222, T1–T9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott-Moncrieff, J.C. Insulin resistance in cats. Vet. Clin. North Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2010, 40, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosca, M.; Forcada, Y.; Solcan, G.; Church, D.B.; Niessen, S.J.M. Screening Diabetic Cats for Hypersomatotropism: Performance of an Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay for Insulin-Like Growth Factor 1. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2014, 16, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niessen, S.J.M.; Hazuchova, K.; Powney, S.L.; Guitian, J.; Niessen, A.P.M.; Pion, P.D.; Shaw, J.A.; Church, D.B. The Big Pet Diabetes Survey: Perceived Frequency and Triggers for Euthanasia. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zini, E.; Hafner, M.; Osto, M.; Franchini, M.; Ackermann, M.; Lutz, T.A.; Reusch, C.E. Predictors of clinical remission in cats with diabetes mellitus. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2010, 24, 1314–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict, S.L.; Mahony, O.M.; McKee, T.S.; Bergman, P.J. Evaluation of Bexagliflozin in Cats with Poorly Regulated Diabetes Mellitus. Can. J. Vet. Res. 2022, 86, 52–58, Erratum in Can. J. Vet Res. 2023, 87, 152. PMID: 34975223; PMCID: PMC8697324.. [Google Scholar]

- Hadd, M.J.; Bienhoff, S.E.; Little, S.E.; Geller, S.; Ogne-Stevenson, J.; Dupree, T.J.; Scott-Moncrieff, J.C. Safety and Effectiveness of the Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter Inhibitor Bexagliflozin in Cats. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2023, 37, 915–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.H.; Choi, H.S.; Choi, J.S.; Lim, H.W.; Huh, W.; Oh, Y.I.; Park, J.S.; Han, J.; Lim, S.; Lim, C.Y.; et al. Effect of the sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor, DWP16001, as an add-on therapy to insulin for diabetic dogs: A pilot study. Vet. Med. Sci. 2024, 10, e1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilla, R.; Suchodolski, J.S. The Role of the Canine Gut Microbiome and Metabolome in Health and Gastrointestinal Disease. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 6, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wernimont, S.M.; Radosevich, J.; Jackson, M.I.; Ephraim, E.; Badri, D.V.; MacLeay, J.M.; Jewell, D.E.; Suchodolski, J.S. The Effects of Nutrition on the Gastrointestinal Microbiome of Cats and Dogs: Impact on Health and Disease. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Q.; Wu, Z. Gut Probiotics and Health of Dogs and Cats: Benefits, Mechanisms and Strategies. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minamoto, Y.; Minamoto, T.; Isaiah, A.; Sattasathuchana, P.; Buono, A.; Rangachari, V.R.; McNeely, I.H.; Lidbury, J.; Steiner, J.M.; Suchodolski, J.S. Fecal short-chain fatty acid concentrations and dysbiosis in dogs with chronic enteropathy. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2019, 33, 1608–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieler, I.N.; Osto, M.; Hugentobler, L.; Puetz, L.; Gilbert, M.T.P.; Hansen, T.; Pedersen, O.; Reusch, C.E.; Zini, E.; Lutz, T.A.; et al. Diabetic cats have decreased gut microbial diversity and a lack of butyrate producing bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jergens, A.E.; Guard, B.C.; Redfern, A.; Rossi, G.; Mochel, J.P.; Pilla, R.; Chandra, L.; Seo, Y.-J.; Steiner, J.M.; Lidbury, J.; et al. Microbiota-Related Changes in Unconjugated Fecal Bile Acids Are Associated With Naturally Occurring, Insulin-Dependent Diabetes Mellitus in Dogs. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeon, K.D.; Kim, S.M.; Kim, J.H. Association between Gut Microbiota and Metabolic Health and Obesity Status in Cats. Animals 2024, 14, 2524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, C.; Cross, T.-W.L.; Devendran, S.; Neumer, F.; Theis, S.; Ridlon, J.M.; Suchodolski, J.S.; de Godoy, M.R.C.; Swanson, K.S. Effects of prebiotic inulin-type fructans on blood metabolite and hormone concentrations and faecal microbiota and metabolites in overweight dogs. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 120, 711–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macedo, H.T.; Rentas, M.F.; Vendramini, T.H.A.; Macegoza, M.V.; Amaral, A.R.; Jeremias, J.T.; de Carvalho Balieiro, J.C.; Pfrimer, K.; Ferriolli, E.; Pontieri, C.F.F.; et al. Weight-loss in obese dogs promotes important shifts in fecal microbiota profile to the extent of resembling microbiota of lean dogs. Anim. Microbiome 2022, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. FDA CBER. Early Clinical Trials with Live Biotherapeutic Products: Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Control Information (Guidance for Industry). 2016. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/early-clinical-trials-live-biotherapeutic-products-chemistry-manufacturing-and-control-information (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Ouwehand, A.C. A review of dose-responses of probiotics in human studies. Benef. Microbes 2017, 8, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandri, G.; van Sinderen, D.; Ventura, M. The genus bifidobacterium: From genomics to functionality of an important component of the mammalian gut microbiota running title: Bifidobacterial adaptation to and interaction with the host. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1472–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, T.; Liu, R.; Sui, W.; Zhu, J.; Fang, S.; Geng, J.; Zhang, M. The Antidiabetic Effects of Bifidobacterium longum subsp. longum BL21 through Regulating Gut Microbiota Structure in Type 2 Diabetic Mice. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 9947–9958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinical Pathology Laboratory. Animal Health Diagnostic Center, Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. Available online: https://www.vet.cornell.edu/animal-health-diagnostic-center/testing-laboratories/clinical-pathology (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Feldman, E.C.; Nelson, R.W. Canine and Feline Endocrinology and Reproduction, 3rd ed.; Saunders: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2004; pp. 486–538. [Google Scholar]

- Sparkes, A.H.; Cannon, M.; Church, D.; Fleeman, L.; Harvey, A.; Hoenig, M.; Mather, E.; Ramsey, I.; Reusch, C.E.; Rosenberg, D. ISFM Consensus Guidelines on the Practical Management of Diabetes Mellitus in Cats. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2015, 17, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Kuczynski, J.; Stombaugh, J.; Bittinger, K.; Bushman, F.D.; Costello, E.K.; Fierer, N.; Peña, A.G.; Goodrich, J.K.; Gordon, J.I.; et al. QIIME Allows Analysis of High-Throughput Community Sequencing Data. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, G.M.; Maffei, V.J.; Zaneveld, J.R.; Yurgel, S.N.; Brown, J.R.; Taylor, C.M.; Fisher, H.S.; Wright, A.J.; Taylor, B.C.; Langille, M.G.I. PICRUSt2 for Prediction of Metagenome Functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 685–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, E.; Montagnana, M.; Nouvenne, A.; Lippi, G. Advantages and Pitfalls of Fructosamine and Glycated Albumin in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Diabetes. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2015, 9, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, D.E.; Little, R.R.; Lorenz, R.A.; Malone, J.I.; Nathan, D.; Peterson, C.M.; Sacks, D.B. Tests of Glycemia in Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 1761–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazanfari, Z.; Haghdoost, A.A.; Alizadeh, S.M.; Atapour, J.; Zolala, F. A Comparison of HbA1c and Fasting Blood Sugar Tests in General Population. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2010, 1, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, X.; Mao, B.; Gu, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Chen, W. Blautia—A New Functional Genus with Potential Probiotic Properties. Gut Microbes 2021, 13, 1875796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, C.A.; Park, B.; Scarsella, E.; Jospin, G.; Entrolezo, Z.; Jarett, J.K.; Martin, A.; Ganz, H.H. Species-Level Characterization of the Core Microbiome in Healthy Dogs Using Full-Length 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1405470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, M.; Ikeyama, N.; Ohkuma, M. Faecalimonas umbilicata gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from human faeces, and reclassification of Eubacterium contortum, Eubacterium fissicatena and Clostridium oroticum as Faecalicatena contorta gen. nov., comb. nov., Faecalicatena fissicatena comb. nov. and Faecalicatena orotica comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 1219–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, M.; Yuki, M.; Ikeyama, N.; Ohkuma, M. Draft Genome Sequence of Faecalimonas umbilicata JCM 30896T, an Acetate-Producing Bacterium. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2018, 7, e01091–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Lin, X.; Jian, S.; Wen, J.; Jian, X.; He, S.; Wen, C.; Liu, T.; Qi, X.; Yin, Y.; et al. Changes in Gut Microbiota and Short-Chain Fatty Acids Are Involved in the Process of Canine Obesity after Neutering. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 101, skad218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, C.C.; Cheng, A.; Huang, Y.T.; Chung, K.P.; Lee, M.R.; Liao, C.H.; Hsueh, P.R. Escherichia fergusonii Bacteremia in a Cancer Patient with Pancreatic Cancer. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 4001–4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crost, E.H.; Coletto, E.; Bell, A.; Juge, N. Ruminococcus gnavus: Friend or Foe for Human Health. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 10, fuad014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourafa, N.; Loucif, L.; Boutefnouchet, N.; Rolain, J.M. Enterococcus hirae, an unusual pathogen in humans causing urinary tract infection in a patient with benign prostatic hyperplasia: First case report in Algeria. New Microbes New Infect. 2015, 8, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, W.; Liu, H.; Fanning, S.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, F. Genomic insights into the pathogenicity and environmental adaptability of Enterococcus hirae R17 isolated from pork offered for retail sale. MicrobiologyOpen 2017, 6, e00514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, Y.; Tomida, J.; Morita, Y.; Fujii, S.; Okamoto, R.; Akita, H.; Kawamura, S.; Kanemitsu, K.; Inoue, M. Clinical and Bacteriological Characteristics of Helicobacter cinaedi Infection. J. Infect. Chemother. 2014, 20, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathur, A.; Kay, C.; Xue, Y.; Pandey, A.; Lee, J.; Jing, W.; Enosi Tuipulotu, D.; Lo Pilato, J.; Feng, S.; Ngo, C.; et al. Clostridium perfringens Virulence Factors Are Nonredundant Activators of the NLRP3 Inflammasome. EMBO Rep. 2023, 24, e54600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnossin, D.; Smith, A.; Oravcová, K.; Weir, W. Streptococcus canis, the Underdog of the Genus. Vet. Microbiol. 2022, 273, 109524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araoka, H.; Baba, M.; Kimura, M.; Abe, M.; Inagawa, H.; Yoneyama, A. Clinical Characteristics of Bacteremia Caused by Helicobacter cinaedi and Time Required for Blood Cultures to Become Positive. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 1519–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Wei, F.; Li, X.; Feng, Y.; Jin, X.; Liu, D.; Guo, Y.; Hu, Y. Inulin-enriched Megamonas funiformis ameliorates metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease by producing propionic acid. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2023, 9, 84, Erratum in npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-024-00480-1.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, M.S.; Seekatz, A.M.; Koropatkin, N.M.; Kamada, N.; Hickey, C.A.; Wolter, M.; Pudlo, N.A.; Kitamoto, S.; Terrapon, N.; Muller, A.; et al. A Dietary Fiber-Deprived Gut Microbiota Degrades the Colonic Mucus Barrier and Enhances Pathogen Susceptibility. Cell 2016, 167, 1339–1353.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, A.; Juge, N. Mucosal Glycan Degradation of the Host by the Gut Microbiota. Glycobiology 2021, 31, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, T.; Murtaza, G.; Kalhoro, D.H.; Kalhoro, M.S.; Metwally, E.; Chughtai, M.I.; Mazhar, M.U.; Khan, S.A. Relationship between Gut Microbiota and Host Metabolism: Emphasis on Hormones Related to Reproductive Function. Anim. Nutr. 2021, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diviccaro, S.; Giatti, S.; Cioffi, L.; Chrostek, G.; Melcangi, R.C. The Gut-Microbiota-Brain Axis: Focus on Gut Steroids. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2025, 37, e13471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, P.S.; Seyed Hameed, A.S.; Meng, X.; Liu, W. Utilization of glycosaminoglycans by the human gut microbiota: Participating bacteria and their enzymatic machineries. Gut Microbes. 2022, 14, 2068367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandri, G.; Milani, C.; Mancabelli, L.; Longhi, G.; Anzalone, R.; Lugli, G.A.; Duranti, S.; Turroni, F.; Ossiprandi, M.C.; van Sinderen, D.; et al. Deciphering the Bifidobacterial Populations within the Canine and Feline Gut Microbiota. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e02875-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Obin, M.S.; Zhao, L. The gut microbiota, obesity and insulin resistance. Mol. Asp. Med. 2013, 34, 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anachad, O.; Taouil, A.; Taha, W.; Bennis, F.; Chegdani, F. The implication of short-chain fatty acids in obesity and diabetes. Microbiol. Insights 2023, 16, 11786361231162720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Dogs (n = 9) | Cats (n = 13) |

|---|---|---|

| Breed | Poodle (n = 4), Maltese (n = 2), Miniature Pinscher (n = 1), Pomeranian (n = 1), Shih Tzu-Poodle Mix (n = 1) | Korean Shorthair (n = 6), Abyssinian (n = 2), Turkish Angora (n = 2), Russian Blue (n = 2), Bengal (n = 1) |

| Age, years Median (Min–Max) | 12 (8–14) | 11 (6–15) |

| Sex | Castrated male (4), Castrated female (5) | Castrated male (11), Castrated female (2) |

| Body weight, kg Median (Min–Max) | 5.0 (4.0–6.7) | 6.4 (4.5–8.6) |

| Category | Parameters | Unit | Dogs | Cats | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Range | Baseline (Week 0) | Week 6 | Week 12 | Reference Range | Baseline (Week 0) | Week 6 | Week 12 | |||

| Complete Blood Count (CBC) | WBC | 109/L | 5.5–19.5 | 11.4 ± 3.1 | 9.0 ± 2.4 | 11.4 ± 5.2 | 5.5–19.5 | 17.3 ± 6.6 | 16.3 ± 7.3 | 15.9 ± 8.2 |

| RBC | 1012/L | 4.6–10 | 6.8 ± 1.1 | 6.7 ± 1.2 | 6.7 ± 1.2 | 4.6–10.0 | 8.4 ± 1.9 | 8.2 ± 1.4 | 8.6 ± 1.6 | |

| HGB | g/dL | 9.3–15.3 | 15.3 ± 2.3 | 15.6 ± 2.5 | 15.7 ± 2.6 | 9.3–15.3 | 13.3 ± 2.7 | 13.5 ± 2.1 | 13.8 ± 2.3 | |

| HCT | % | 28–49 | 46.2 ± 6.9 | 46.0 ± 8.6 | 46.8 ± 9.0 | 28–49.0 | 42.6 ± 8.3 | 41.5 ± 6.2 | 43.6 ± 6.2 | |

| PLT | 109/L | 100–514 | 371.6 ± 172.0 | 408.8 ± 157.6 | 378.7 ± 143.6 | 100–514.0 | 200.1 ± 172.4 | 190.7 ± 95.4 | 194.6 ± 105.4 | |

| Serum Biochemistry | TP | g/dL | 5.5–7.2 | 7.2 ± 0.8 | 7.0 ± 0.7 | 12.9 ± 18.2 | 6.6–8.4 | 8.4 ± 1.0 | 8.4 ± 0.7 | 8.2 ± 0.7 |

| ALB | g/dL | 3.2–4.1 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 3.2–4.3 | 3.7 ± 0.6 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | 3.8 ± 0.4 | |

| ALP | U/L | 7–115 | 590.3 ± 606.1 | 522.4 ± 420.9 | 589.9 ± 511.5 | 11–49.0 | 47.6 ± 19.6 | 43.0 ± 26.4 | 50.4 ± 26.6 | |

| TBIL | mg/dL | 0–0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1–0.5 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | |

| IP | mg/dL | 2.7–5.4 | 4.4 ± 0.7 | 4.1 ± 1.1 | 4.4 ± 0.9 | 2.6–5.5 | 4.8 ± 0.9 | 4.5 ± 1.2 | 4.2 ± 1.5 | |

| TC | mg/dL | 136–392 | 396.2 ± 165.5 | 409.9 ± 180.0 | 462.7 ± 257.5 | 101–323.0 | 231.5 ± 65.6 | 244.4 ± 89.9 | 243.5 ± 81.1 | |

| GGT | U/L | 0–8 | 8.6 ± 6.2 | 7.5 ± 8.7 | 15.9 ± 12.0 | 0–2.0 | 3.0 ± 1.4 | 7.2 ± 4.9 | 3.7 ± 2.5 | |

| ALT | U/L | 17–95 | 168.8 ± 175.4 | 102.0 ± 78.7 | 154.6 ± 137.4 | 22–84.0 | 90.1 ± 56.6 | 77.1 ± 45.0 | 71.2 ± 33.0 | |

| Ca | mg/dL | 9.4–11.1 | 10.7 ± 0.6 | 10.6 ± 1.4 | 9.9 ± 0.5 | 9–11.3 | 10.7 ± 0.8 | 9.7 ± 1.8 | 10.0 ± 0.6 | |

| CRE | mg/dL | 0.6–1.4 | 0.7 ± 0.3 | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 0.5 ± 0.3 | 0.8–2.1 | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 3.6 ± 7.5 | |

| BUN | mg/dL | 9–26 | 26.2 ± 16.7 | 26.8 ± 16.7 | 28.5 ± 16.8 | 17–35.0 | 34.0 ± 10.1 | 37.0 ± 12.0 | 28.9 ± 11.6 | |

| GLOB | g/dL | 1.9–3.7 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 9.5 ± 18.3 | 2.9–4.7 | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 4.6 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 0.5 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Choi, Y.; Kim, J.-E.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, S.; Shin, C.H. Glucose-Lowering Effects and Safety of Bifidobacterium longum CKD1 in Diabetic Dogs and Cats. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2881. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122881

Choi Y, Kim J-E, Kim KH, Lee S, Shin CH. Glucose-Lowering Effects and Safety of Bifidobacterium longum CKD1 in Diabetic Dogs and Cats. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2881. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122881

Chicago/Turabian StyleChoi, Yukyung, Ji-Eun Kim, Kyung Hwan Kim, Sunghee Lee, and Chang Hun Shin. 2025. "Glucose-Lowering Effects and Safety of Bifidobacterium longum CKD1 in Diabetic Dogs and Cats" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2881. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122881

APA StyleChoi, Y., Kim, J.-E., Kim, K. H., Lee, S., & Shin, C. H. (2025). Glucose-Lowering Effects and Safety of Bifidobacterium longum CKD1 in Diabetic Dogs and Cats. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2881. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122881