Synergistic Effects of Fertilization and Reclamation Age on Inorganic Phosphorus Fractions and the pqqC-Harboring Bacterial Community in Reclaimed Coal Mining Soils

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site and Design

2.2. Soil Sampling and Chemical Analysis

2.3. Analysis of Soil Inorganic Phosphorus Fractions

2.4. Soil DNA Extraction, pqqC Gene Quantification, and Sequencing

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Soil Nutrients and Phosphorus Fractions in Reclaimed Soil

3.1.1. Soil Nutrients

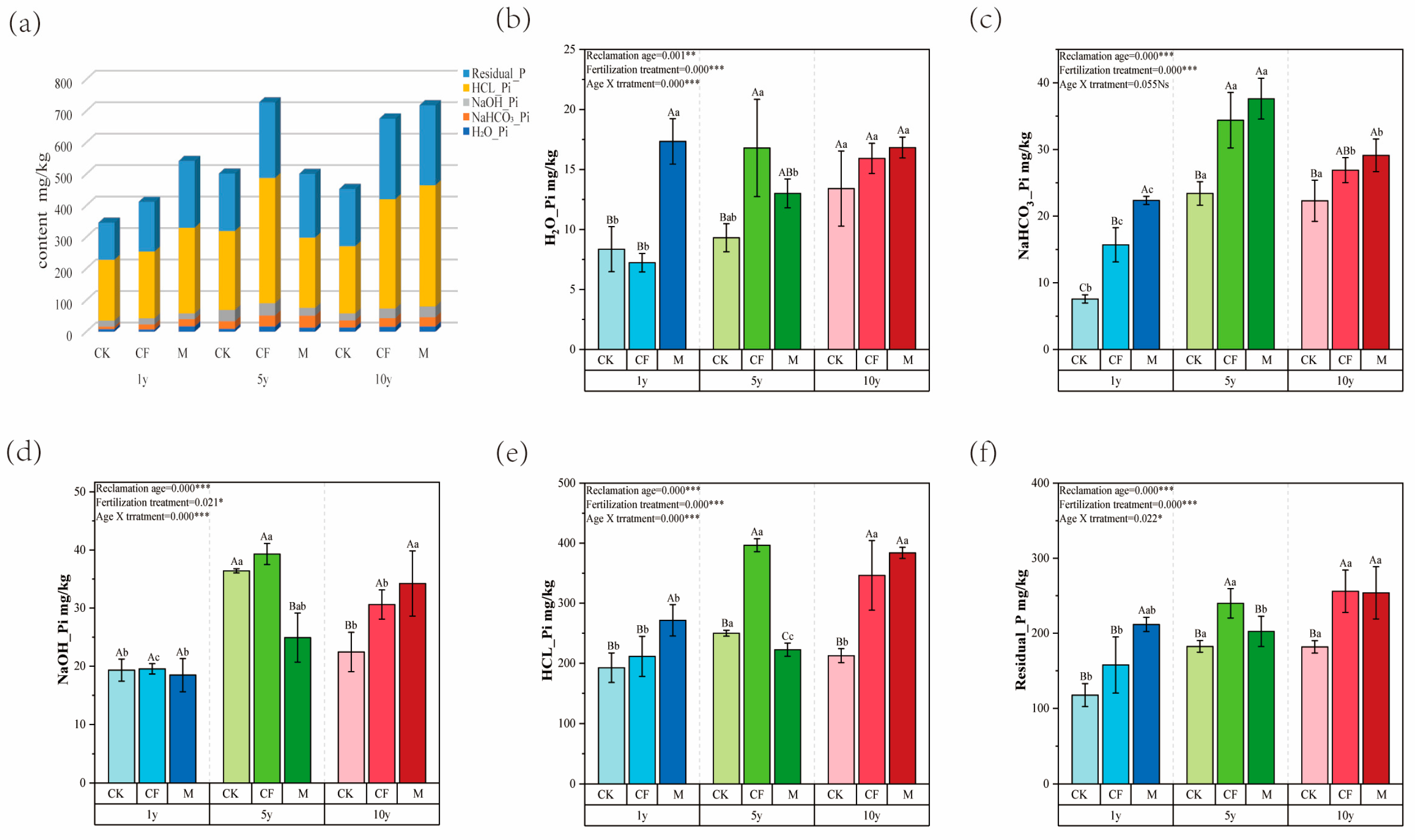

3.1.2. Distribution of Inorganic Phosphorus Fractions

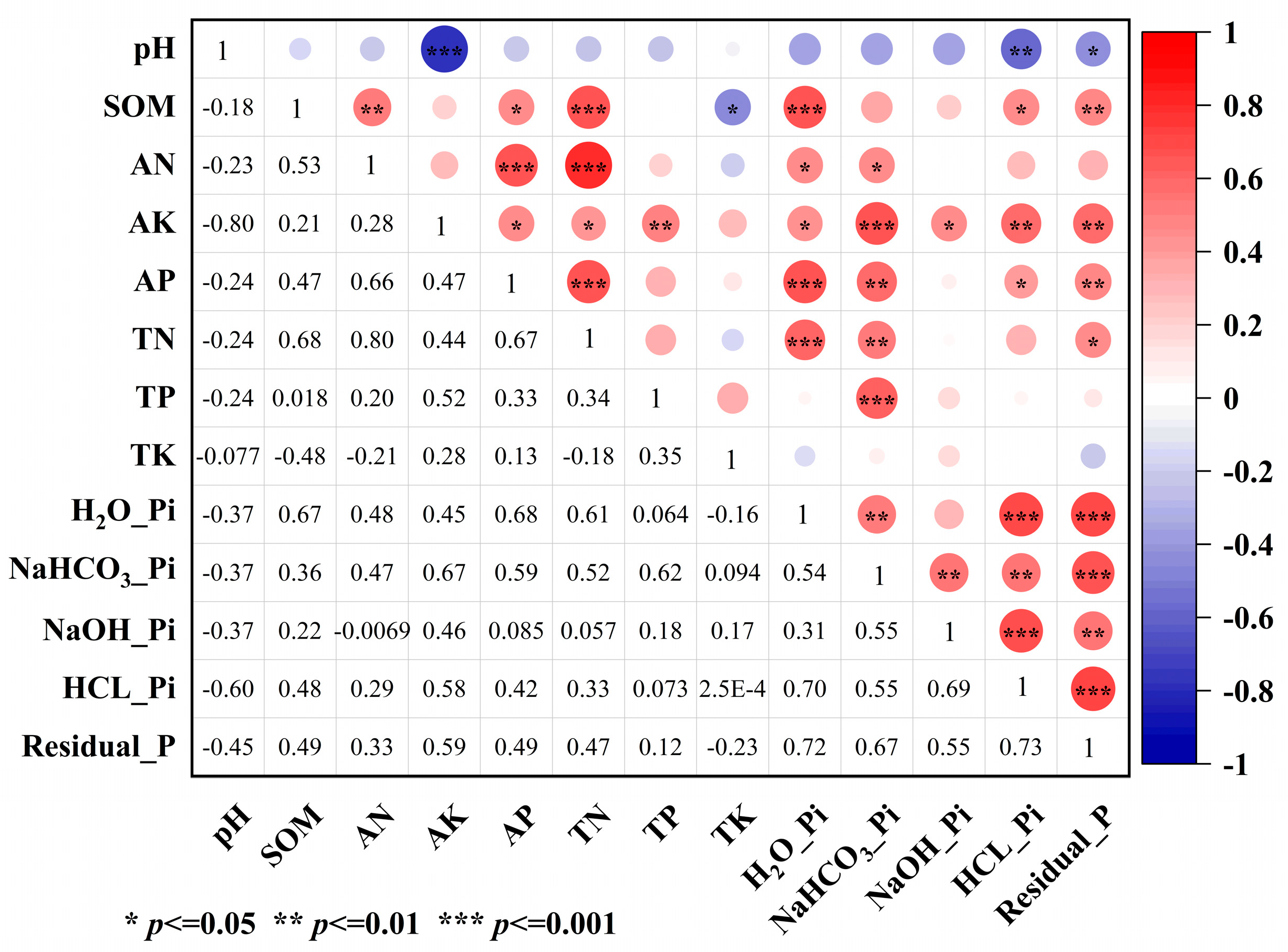

3.1.3. Relationships Between Soil Nutrients and Phosphorus Fractions

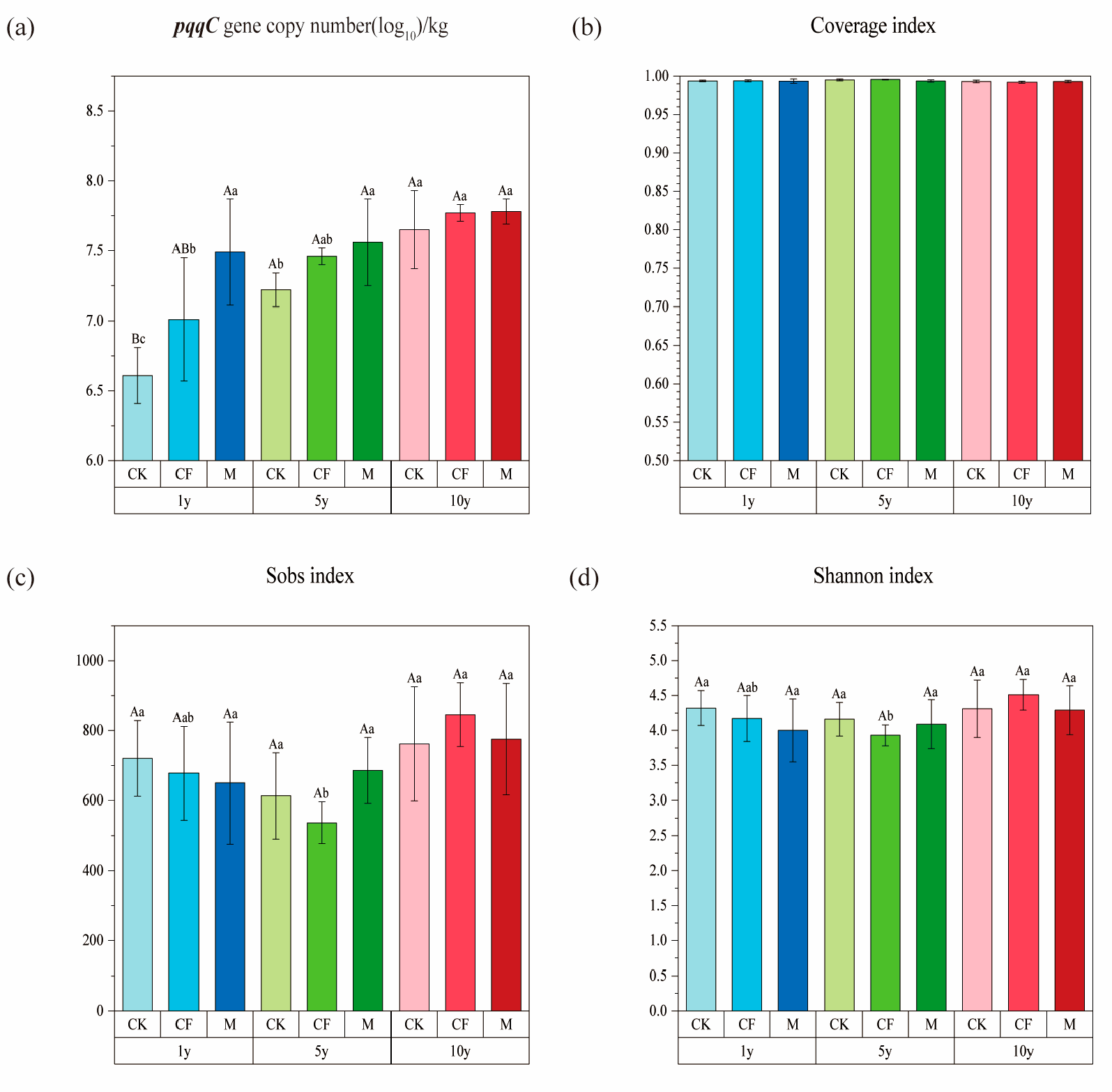

3.2. pqqC Gene Abundance and α-Diversity

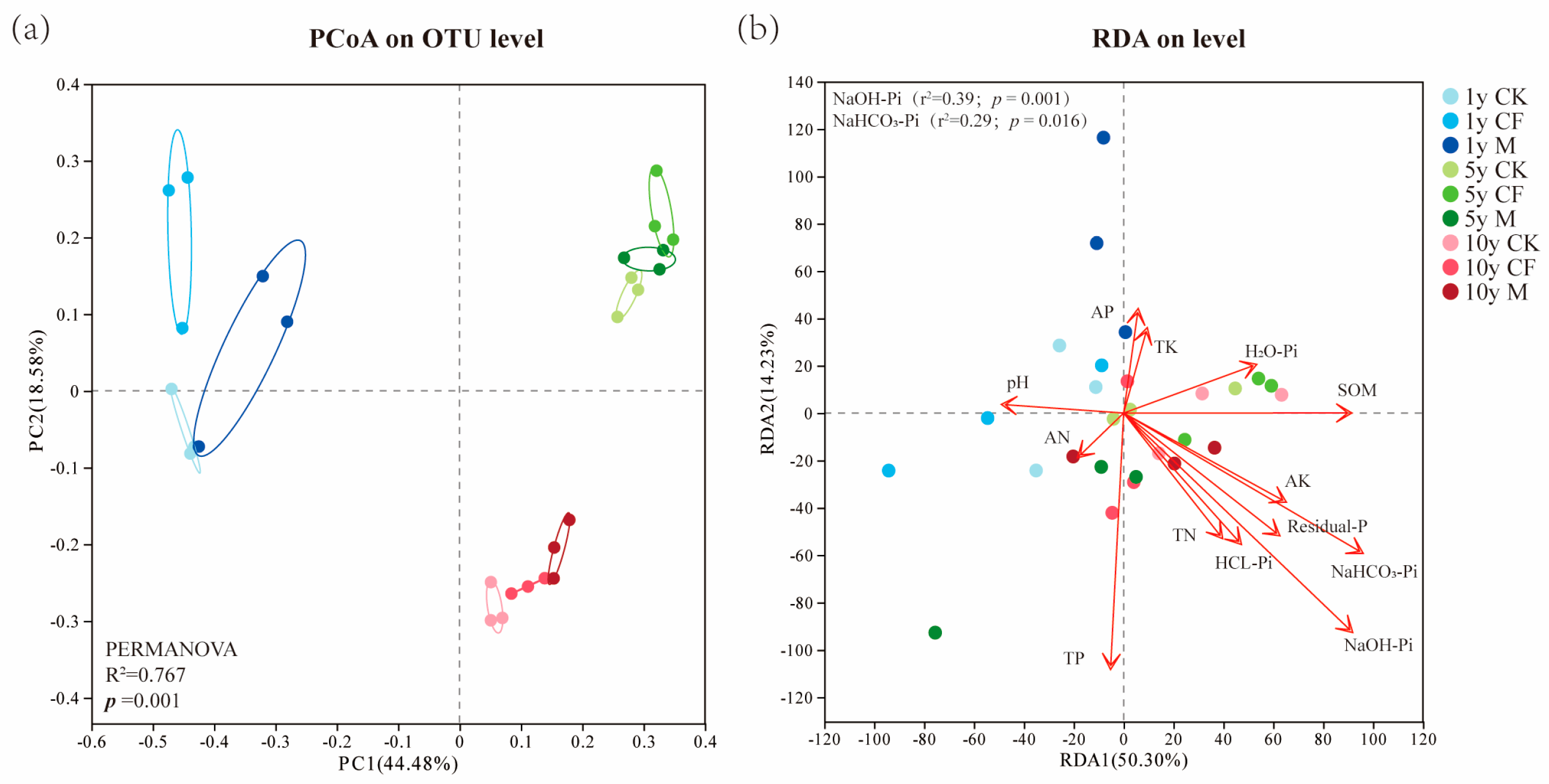

3.3. Composition of the pqqC-Harboring Bacterial Community

3.4. Microbial Community Structure and Environmental Drivers

3.5. Co-Occurrence Network Analysis of Core Taxa

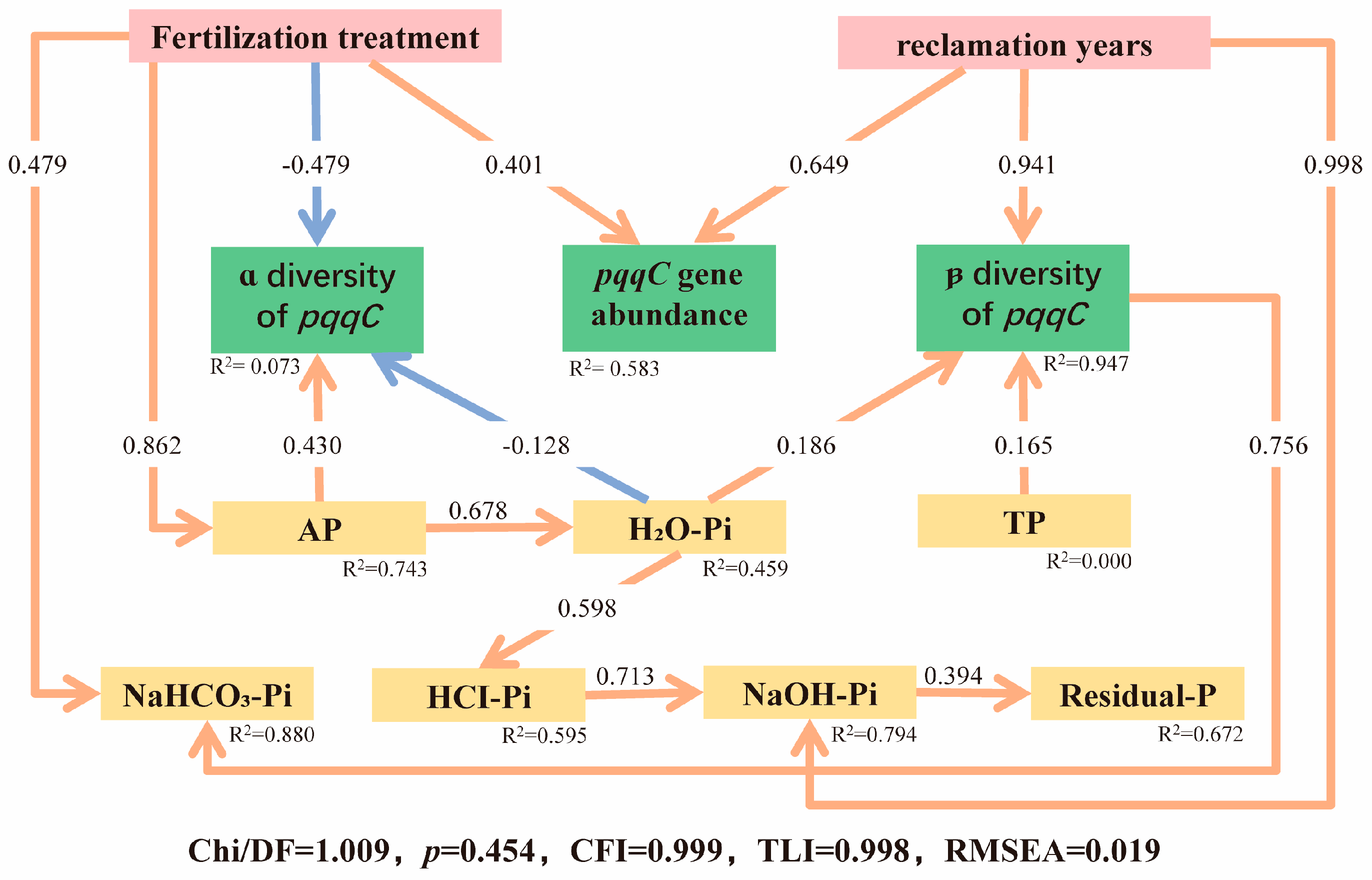

3.6. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of Reclamation Age and Fertilization on the Soil Phosphorus Pool and Its Availability

4.2. Effects of Reclamation Age and Fertilization on the pqqC Gene Abundance and Microbial Community

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ouyang, S.; Huang, Y.; Gao, H.; Guo, Y.; Wu, L.; Li, J. Study on the distribution characteristics and ecological risk of heavy metal elements in coal gangue taken from 25 mining areas of China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 48285–48300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wang, J.; Bai, Z.; Reading, L. Effects of surface coal mining and land reclamation on soil properties: A review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2019, 191, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Xu, F.; Lin, T.; Xu, Q.; Yu, P.; Wang, C.; Aili, A.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, P.; et al. A systematic review and comprehensive analysis on ecological restoration of mining areas in the arid region of China: Challenge, capability and reconsideration. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Wei, Y.; Meng, H.; Cao, Y.; Lead, J.; Hong, J. Effects of fertilization and reclamation time on soil bacterial communities in coal mining subsidence areas. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 739, 139882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidson, E.A.; de Carvalho, C.J.R.; Vieira, I.C.G.; Figueiredo, R.d.O.; Moutinho, P.; Ishida, F.Y.; dos Santos, M.T.P.; Guerrero, J.B.; Kalif, K.; Sabá, R.T. Nitrogen and Phosphorus Limitation of Biomass Growth in a Tropical Secondary Forest. Ecol. Appl. 2004, 14 (Suppl. S4), 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, P.; Das, S.; Shankhdhar, D.; Shankhdhar, S.C. Phosphate-Solubilizing Microorganisms: Mechanism and Their Role in Phosphate Solubilization and Uptake. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 21, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Mir, R.A.; Hussain, S.J.; Prasad, B.; Kumar, P.; Aloo, B.N.; Sharma, C.M.; Dubey, R.C. Prospects of phosphate solubilizing microorganisms in sustainable agriculture. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Liu, G.; Chen, H.; Chen, C.; Wang, J.; Ai, S.; Wei, D.; Li, D.; Ma, B.; Tang, C.; et al. Long-term nutrient inputs shift soil microbial functional profiles of phosphorus cycling in diverse agroecosystems. ISME J. 2020, 14, 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, B.-X.; Hao, X.-L.; Ding, K.; Zhou, G.-W.; Chen, Q.-L.; Zhang, J.-B.; Zhu, Y.-G. Long-term nitrogen fertilization decreased the abundance of inorganic phosphate solubilizing bacteria in an alkaline soil. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, srep42284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Che, S.; Xu, Y.; Qin, X.; Tian, S.; Wang, J.; Zhou, X.; Cao, Z.; Wang, D.; Wu, M.; Wu, Z.; et al. Building microbial consortia to enhance straw degradation, phosphorus solubilization, and soil fertility for rice growth. Microb. Cell Factories 2024, 23, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, H.; Fraga, R.; Gonzalez, T.; Bashan, Y. Genetics of phosphate solubilization and its potential applications for improving plant growth-promoting bacteria. Plant Soil 2006, 287, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Q.-F.; Li, K.-J.; Zheng, B.-X.; Liu, X.-P.; Li, H.-Z.; Jin, B.-J.; Ding, K.; Yang, X.-R.; Lin, X.-Y.; Zhu, Y.-G. Partial replacement of inorganic phosphorus (P) by organic manure reshapes phosphate mobilizing bacterial community and promotes P bioavailability in a paddy soil. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 703, 134977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Wang, R.; Shi, J.; Wang, R.; Guo, S. Nitrogen fertilization management is required for soil phosphorus mobilization by phoD-harboring bacterial community assembly and pqqC-harboring bacterial keystone taxa. Pedosphere 2025, 35, 655–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, L.; Zheng, B.; Xu, Y.; Xu, J.; Peñuelas, J.; Sardans, J.; Chang, Y.; Jin, S.; Ying, H.; Ding, K. Organic fertilizers shape the bacterial communities harboring pqqC and phoD genes by altering organic acids, leading to improved phosphorus utilization. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2025, 7, 250296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brucker, E.; Kernchen, S.; Spohn, M. Release of phosphorus and silicon from minerals by soil microorganisms depends on the availability of organic carbon. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 143, 107737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Xing, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Gao, N.; Ying, Y. Diverse responses ofpqqC- andphoD-harbouring bacterial communities to variation in soil properties of Moso bamboo forests. Microb. Biotechnol. 2022, 15, 2097–2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Yuan, J.; Tang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y. Long-Term Organic Fertilization Strengthens the Soil Phosphorus Cycle and Phosphorus Availability by Regulating the pqqC- and phoD-Harboring Bacterial Communities. Microb. Ecol. 2023, 86, 2716–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerenfes, D.; Giorgis, A.G.; Negasa, G. Comparison of organic matter determination methods in soil by loss on ignition and potassium dichromate method. Int. J. Hortic. Food Sci. 2022, 4, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, P.L. Kjeldahl Method for Total Nitrogen. Anal. Chem. 2002, 22, 354–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Niu, X.; Chen, B.; Pu, S.; Ma, H.; Li, P.; Feng, G.; Ma, X. Chemical fertilizer reduction combined with organic fertilizer affects the soil microbial community and diversity and yield of cotton. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1295722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Song, D.; Liu, M.; Li, Y.; Li, Y. Effects of earthworm activities on soil nutrients and microbial diversity under different tillage measures. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 222, 105441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Xu, C.; Yuan, J.; Xu, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y. Long-term nitrogen fertilization and sweetpotato cultivation in the wheat-sweetpotato rotation system decrease alkaline phosphomonoesterase activity by regulating soil phoD-harboring bacteria communities. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 900, 165916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedley, M.J.; Stewart, J.W.B.; Chauhan, B.S. Changes in Inorganic and Organic Soil Phosphorus Fractions Induced by Cultivation Practices and by Laboratory Incubations. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1982, 46, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiessen, H.; Moir, J.O. Characterization of Available P by Sequential Extraction. Soil Sampl. Methods Anal. 1993, 7, 5–229. [Google Scholar]

- Sui, Y.; Thompson, M.L.; Shang, C. Fractionation of Phosphorus in a Mollisol Amended with Biosolids. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1999, 63, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holford, I.C.R. Soil phosphorus: Its measurement, and its uptake by plants. Soil Res. 1997, 35, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, A.F.; Schlesinger, W.H. A literature review and evaluation of the. Hedley fractionation: Applications to the biogeochemical cycle of soil phosphorus in natural ecosystems. Geoderma 1995, 64, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Zheng, X.; Lv, W.; Qin, Q.; Sun, L.; Zhang, H.; Xue, Y. Effects of tillage and straw return on water-stable aggregates, carbon stabilization and crop yield in an estuarine alluvial soil. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.L.; Liu, K.L.; Xu, Q.F.; Shen, R.F.; Zhao, X.Q. Organic fertilization sustains high maize yields in acid soils through the cooperation of rhizosphere microbes and plants. Plant Soil 2025, 514, 2443–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liang, C.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Cheng, J.; Chang, M.; Xu, J. Effects of manure application on paddy soil phosphorus in China based on a meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, K.; Xiao, W.; Wang, N.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Peng, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, A.; Qi, R.; Yu, F.; et al. Carbon-nitrogen-phosphorus level regulation of potentially toxic elements and enzyme activities in paddy soil aggregates: Straw and organic fertilizer effects. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.Q.; Guo, C.; Ullah, R.; Ahmad, F.; Li, Z.; Ma, H.; Feng, T.; Li, F.-M. Enhancing soil health and microbial resilience with organic fertilization in semi-arid Astragalus ecosystems. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 394, 127474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Li, L.; Friman, V.-P.; Guo, J.; Guo, S.; Shen, Q.; Ling, N. Organic amendments increase crop yields by improving microbe-mediated soil functioning of agroecosystems: A meta-analysis. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 124, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, W.; Ma, L.; Luan, H.; Tang, J.; Li, R.; Li, M.; Huang, S.; Wang, L. Long-term partial substitution of chemical fertilizer by organic amendments influences soil microbial functional diversity of phosphorus cycling and improves phosphorus availability in greenhouse vegetable production. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 341, 108193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Qin, Z.-H.; Zhang, W.-W.; Chen, Y.-H.; Zhu, P.; Peng, C.; Wang, L.; Zhang, S.-X.; Colinet, G. Effect of long-term fertilization on phosphorus fractions in different soil layers and their quantitative relationships with soil properties. J. Integr. Agric. 2022, 21, 2720–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kim, K.; Walitang, D.I.; Sayyed, R.Z.; Sa, T. Shifts in Soil Bacterial Community Composition of Jujube Orchard Influenced by Organic Fertilizer Amendment. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 34, 2539–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Bom, F.; Nunes, I.; Raymond, N.S.; Hansen, V.; Bonnichsen, L.; Magid, J.; Nybroe, O.; Jensen, L.S. Long-term fertilisation form, level and duration affect the diversity, structure and functioning of soil microbial communities in the field. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 122, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holík, L.; Hlisnikovský, L.; Honzík, R.; Trögl, J.; Burdová, H.; Popelka, J. Soil Microbial Communities and Enzyme Activities after Long-Term Application of Inorganic and Organic Fertilizers at Different Depths of the Soil Profile. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Ren, T.; Lu, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Cong, R.; Lu, J. Straw return and phosphorus (P) fertilization shape P-solubilizing bacterial communities and enhance P mobilization in rice-rapeseed rotation systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 381, 109434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francioli, D.; Schulz, E.; Lentendu, G.; Wubet, T.; Buscot, F.; Reitz, T. Mineral vs. Organic Amendments: Microbial Community Structure, Activity and Abundance of Agriculturally Relevant Microbes Are Driven by Long-Term Fertilization Strategies. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Chen, L.; Zhang, J.; Yin, J.; Huang, S. Bacterial Community Structure after Long-term Organic and Inorganic Fertilization Reveals Important Associations between Soil Nutrients and Specific Taxa Involved in Nutrient Transformations. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, S.; Hu, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Bai, L.; Liu, Z.; Xiao, W.; Gong, Z.; Wu, Y.; Feng, K.; Deng, Y.; et al. Application of organic fertilizer improves microbial community diversity and alters microbial network structure in tea (Camellia sinensis) plantation soils. Soil Tillage Res. 2019, 195, 104356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Li, M.; Whelan, M. Phosphorus activators contribute to legacy phosphorus availability in agricultural soils: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 612, 522–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Xue, Y.; Zheng, X.; Lv, W.; Qiao, H.; Qin, Q.; Yang, J. Effects of the continuous use of organic manure and chemical fertilizer on soil inorganic phosphorus fractions in calcareous soil. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Kirkby, C.A.; Schmutter, D.; Bissett, A.; Kirkegaard, J.A.; Richardson, A.E. Network analysis reveals functional redundancy and keystone taxa amongst bacterial and fungal communities during organic matter decomposition in an arable soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 97, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberán, A.; Bates, S.T.; Casamayor, E.O.; Fierer, N. Using network analysis to explore co-occurrence patterns in soil microbial communities. ISME J. 2012, 6, 343–351, Erratum in ISME J. 2014, 8, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Li, G.; Min, K.; Liu, T.; Li, C.; Xu, J.; Hu, F.; Li, H. The potential role of fertilizer-derived exogenous bacteria on soil bacterial community assemblage and network formation. Chemosphere 2022, 287, 132338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zeng, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; He, P.; Li, S.; Liang, G.; Zhou, W.; et al. The stronger impact of inorganic nitrogen fertilization on soil bacterial community than organic fertilization in short-term condition. Geoderma 2021, 382, 114752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Wang, C.; Jiang, L.; Luo, Y. Trends in soil microbial communities during secondary succession. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 115, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guseva, K.; Darcy, S.; Simon, E.; Alteio, L.V.; Montesinos-Navarro, A.; Kaiser, C. From diversity to complexity: Microbial networks in soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 169, 108604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Gao, Z.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, D.; Gao, W.; Jia, M.; Han, G.; Zhang, G. Early-stage reclamation of open-pit mines in arid and semiarid regions: A tri-tiered evaluation of soil bacterial communities, functional genes, and physicochemical properties. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2025, 216, 106503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhaissoufi, W.; Ghoulam, C.; Barakat, A.; Zeroual, Y.; Bargaz, A. Phosphate bacterial solubilization: A key rhizosphere driving force enabling higher P use efficiency and crop productivity. J. Adv. Res. 2022, 38, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Li, H.; Chen, X.; Lang, M. Rhizosphere phosphatase hotspots: Microbial-mediated P transformation mechanisms influenced by maize varieties and phosphorus addition. Plant Soil 2024, 512, 1577–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, L.; George, T.S.; Feng, G. A core microbiome in the hyphosphere of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi has functional significance in organic phosphorus mineralization. New Phytol. 2022, 238, 859–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Ling, N.; Luo, G.; Guo, J.; Zhu, C.; Xu, Q.; Liu, M.; Shen, Q.; Guo, S. Active phoD-harboring bacteria are enriched by long-term organic fertilization. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 152, 108071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Condron, L.M.; Guo, B.; Liu, J.; Qiu, G.; Li, H. Impact of ryegrass cover crop inclusion on soil phosphorus and pqqC- and phoD-harboring bacterial communities. Soil Tillage Res. 2023, 234, 105823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Song, Q.; Shan, X.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Fu, H.; Sun, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, T. Microorganisms regulate soil phosphorus fractions in response to low nocturnal temperature by altering the abundance and composition of the pqqC gene rather than that of the phoD gene. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2023, 59, 973–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shao, Z.; Fang, S.; Cheng, J.; Guo, X.; Zhang, J.; Yu, C.; Mao, T.; Wu, G.; Zhang, H. Soil Inorganic Phosphorus Is Closely Associated with pqqC- Gene Abundance and Bacterial Community Richness in Grape Orchards with Different Planting Years. Agronomy 2025, 15, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Pei, J.; Tian, Z.; Wan, P.; Li, D. Afforestation Enhances Potential Bacterial Metabolic Function without Concurrent Soil Carbon: A Case Study of Mu Us Sandy Land. Forests 2024, 15, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, D.; Jiang, F.; Lin, W.; Tian, Z.; Wu, N.; Feng, X.; Chen, T.; Nan, Z. Effects of Drought on the Growth of Lespedeza davurica through the Alteration of Soil Microbial Communities and Nutrient Availability. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reclamation Age | Fertilization Treatment | pH | SOM (g/kg) | AN (mg/kg) | AK (mg/kg) | AP (mg/kg) | TN (g/kg) | TP (g/kg) | TK (g/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CK | 8.07 ± 0.05 Aa | 7.71 ± 0.94 Ab | 23.89 ± 2.36 Aab | 76.68 ± 4.00 Ac | 1.58 ± 0.41 Bb | 0.53 ± 0.14 Ab | 0.19 ± 0.08 Aa | 14.27 ± 0.22 Aa |

| CF | 7.91 ± 0.04 Ba | 7.88 ± 1.31 Ac | 24.57 ± 3.55 Ab | 164.73 ± 88.32 Ab | 4.92 ± 0.49 Bc | 0.42 ± 0.15 Ab | 0.20 ± 0.01 Aa | 13.97 ± 0.30 ABa | |

| M | 8.01 ± 0.05 Aa | 10.98 ± 3.23 Aa | 30.71 ± 12.79 Aa | 139.38 ± 53.30 Aa | 32.36 ± 9.20 Aa | 0.73 ± 0.38 Aa | 0.19 ± 0.17 Ab | 13.63 ± 0.34 Bab | |

| 5 | CK | 8.11 ± 0.05 Aa | 8.38 ± 0.07 Ab | 16.38 ± 2.05 Cb | 104.70 ± 4.00 Cb | 2.04 ± 0.89 Bb | 0.17 ± 0.05 Cc | 0.25 ± 0.07 Ba | 13.93 ± 0.27 Aa |

| CF | 7.73 ± 0.11 Bb | 9.64 ± 0.59 Ab | 26.62 ± 2.05 Bb | 288.80 ± 4.00 Aa | 19.33 ± 3.18 Aa | 0.71 ± 0.11 Ba | 0.55 ± 0.27 ABa | 15.31 ± 1.37 Aa | |

| M | 7.99 ± 0.08 Aa | 9.76 ± 1.38 Aa | 40.27 ± 6.58 Aa | 195.42 ± 8.33 Ba | 27.45 ± 6.63 Aa | 1.10 ± 0.10 Aa | 0.69 ± 0.13 Aa | 14.14 ± 0.45 Aa | |

| 10 | CK | 8.03 ± 0.03 Aa | 11.94 ± 1.26 Aa | 27.98 ± 8.52 Aa | 126.04 ± 8.33 Ca | 4.13 ± 0.63 Ba | 0.79 ± 0.04 Aa | 0.24 ± 0.06 Aa | 12.25 ± 0.20 Bb |

| CF | 7.82 ± 0.07 Bab | 12.30 ± 0.35 Aa | 33.44 ± 3.13 Aa | 194.08 ± 14.06 Aab | 13.37 ± 1.78 ABb | 0.88 ± 0.03 Aa | 0.32 ± 0.29 Aa | 11.99 ± 0.20 Bb | |

| M | 8.01 ± 0.03 Aa | 12.53 ± 0.81 Aa | 37.54 ± 5.15 Aa | 159.40 ± 22.76 Ba | 21.69 ± 7.96 Aa | 1.00 ± 0.21 Aa | 0.14 ± 0.18 Ab | 13.07 ± 0.15 Ab | |

| Two-way ANOVA (p values) | |||||||||

| Reclamation age | 0.140 Ns | 0.000 *** | 0.083 Ns | 0.003 ** | 0.274 Ns | 0.002 ** | 0.002 ** | 0.000 *** | |

| Fertilization treatment | 0.000 *** | 0.048 * | 0.001 ** | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.235 Ns | 0.557 Ns | |

| Age X treatment | 0.038 * | 0.309 Ns | 0.186 Ns | 0.093 Ns | 0.009 ** | 0.005 ** | 0.091 Ns | 0.007 ** | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fang, Z.; Liu, K.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, J.; Song, Z.; Meng, H.; Hao, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X. Synergistic Effects of Fertilization and Reclamation Age on Inorganic Phosphorus Fractions and the pqqC-Harboring Bacterial Community in Reclaimed Coal Mining Soils. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 2855. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122855

Fang Z, Liu K, Jiang Y, Wang J, Song Z, Meng H, Hao X, Zhang J, Wang X. Synergistic Effects of Fertilization and Reclamation Age on Inorganic Phosphorus Fractions and the pqqC-Harboring Bacterial Community in Reclaimed Coal Mining Soils. Microorganisms. 2025; 13(12):2855. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122855

Chicago/Turabian StyleFang, Zhiwen, Kunli Liu, Yunlong Jiang, Jianfang Wang, Zhuomin Song, Huisheng Meng, Xianjun Hao, Jie Zhang, and Xiangying Wang. 2025. "Synergistic Effects of Fertilization and Reclamation Age on Inorganic Phosphorus Fractions and the pqqC-Harboring Bacterial Community in Reclaimed Coal Mining Soils" Microorganisms 13, no. 12: 2855. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122855

APA StyleFang, Z., Liu, K., Jiang, Y., Wang, J., Song, Z., Meng, H., Hao, X., Zhang, J., & Wang, X. (2025). Synergistic Effects of Fertilization and Reclamation Age on Inorganic Phosphorus Fractions and the pqqC-Harboring Bacterial Community in Reclaimed Coal Mining Soils. Microorganisms, 13(12), 2855. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms13122855